Abstract

Client-initiated workplace violence in educational settings is a global issue affecting both teaching and non-teaching employees, such as instructional assistants, counselors, and administrators, among other school workers. Although studies on violence in educational settings have primarily focused on students, there has been growing interest in examining violence against teachers and, more recently, against teaching assistants and other educational professionals. This systematic review aims to analyze studies from diverse educational settings to examine the characteristics, causes, effects, and coping strategies associated with violence perpetrated by students, parents, or guardians, with the goal of informing and advancing prevention strategies. Following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, a systematic literature review was conducted, analyzing studies across various educational environments to examine the characteristics, causes, effects, and coping strategies of violence perpetrated by students, parents, or guardians. This review revealed a significant prevalence of physical, psychological, and verbal assaults. However, most studies originated from Anglo-Saxon contexts, limiting their generalizability to diverse cultural and educational settings. The lack of research in other languages and in underrepresented regions highlights critical gaps in understanding this issue globally. The revision conclude that workplace violence in educational settings demands urgent and comprehensive responses involving all stakeholders. Implementing targeted prevention strategies and fostering a culture of respect are essential to ensure safe and healthy learning environments.

1. Introduction

External workplace violence refers to direct exposure to negative, systematic, and prolonged behaviors at work (Notelaers & Einarsen, 2013). When external violence is perpetrated by a client or user of an organization, it is classified as client violence (NIOSH, 2020). Workplace violence, in all its forms, has been recognized as a global issue that continues to rise and has severe effects on individuals and organizations (Palma Contreras et al., 2018). Specifically, client violence has been defined as a public health issue (Díaz Berr et al., 2015) due to its prevalence (Sicora et al., 2022) and its negative impacts (Mento et al., 2020).

Client violence, characterized by the existence of a professional relationship between the perpetrator and the worker, typically occurs during the exchange of goods and services (Diaz et al., 2018). This form of violence is particularly prevalent in the health and education sectors, due to the unique relationship between workers and users (Magnavita et al., 2019).

Although studies on violence in educational settings have primarily focused on students (Benbenishty et al., 2019), there has been growing interest in examining violence against teachers, and, more recently, against teaching assistants and other educational professionals1 (Holt & Birchall, 2023). Evidence suggests that violence is widespread among workers in the education sector, with higher risks for teaching assistants, women, and younger workers. Moreover, this violence significantly impacts workers, organizations, and the broader educational community (Longobardi et al., 2019; Schofield et al., 2022).

While research on violence against educational workers has progressed, prevention efforts have predominantly been developed from the perspective of the school climate (Baker-Henningham et al., 2019; Schultes et al., 2015). School climate, understood as the set of interactions and relationships within the educational community, is not only a key focus of educational policies but also a learning objective for academic development (Política Nacional de Convivencia Educativa, 2024). Within this framework, violence against workers is addressed as an educational policy issue, but remains overlooked as a health concern, similar to other social services such as healthcare and caregiving, where violence is often justified as an inherent part of the job (Lamothe et al., 2018). Consequently, there is limited evidence on the specific practices and plans for preventing client violence in this context.

Building upon this problem, this study seeks to answer the following research question: what are the characteristics, causes, effects, and coping strategies of client violence in educational settings when students, parents, or guardians perpetrate the aggression? This question aims to identify not only the factors that contribute to the occurrence of this phenomenon but also the tools available that are necessary to address its consequences.

This study is crucial because it addresses a significant gap in the literature driven by the limited information available on preventive actions against client-initiated violence in educational settings. By systematically exploring the elements related to client violence in the educational context and considering its implications as a public health issue, this review seeks to generate evidence that informs the design of comprehensive prevention strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

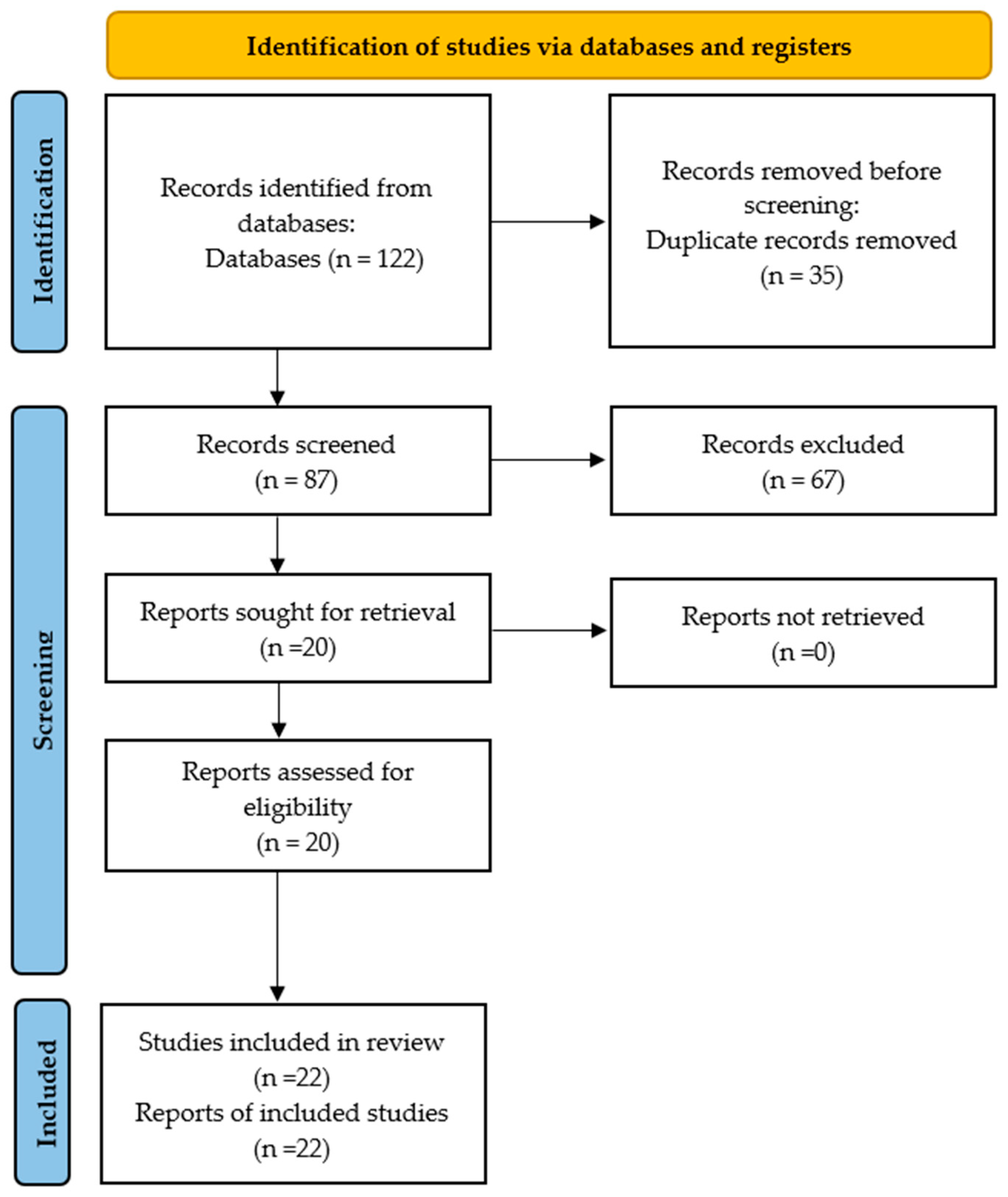

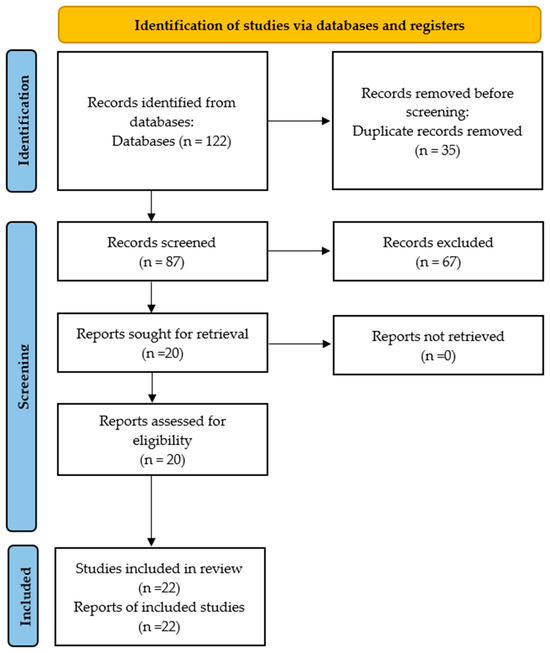

To meet the study’s objectives, a systematic literature review was conducted following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The PRISMA checklist was followed to ensure transparency and rigor in the review process.

As a preliminary step, the review involved identifying key concepts related to the main terms used in the literature on this topic. This process was carried out through multiple searches and iterations. The primary sources for document collection included websites and international journal databases, such as ProQuest, WOS, and SCOPUS. Once the relevant topics and keywords associated with violence against teachers and other educational workers were identified, a systematic review of the literature was performed. This approach aligned with the aim of addressing a specific and focused research question using prior studies (Martínez-Usarralde et al., 2019).

The review focused on identifying publications that reported research on violence against educational workers. Searches were conducted using three databases—WoS, SCOPUS, and ProQuest—and included articles in both English and Spanish published between 2013 and 2023 that contained the identified keywords in their titles.

The search targeted key concepts that were classified into three categories:

- (a)

- To identify workers experiencing violence: terms such as “teacher” OR “educators” OR “school employees” OR “school workers” OR “education workers” OR “education employees” were used.

- (b)

- To identify the locations where violence occurs: keywords like “school” OR “high school” OR “middle school” OR “preschool” OR “special education” OR “classroom” were employed.

- (c)

- To determine the type of violence: concepts such as “violence” OR “workplace violence” OR “client violence” OR “type 2 violence” were used.

Following these criteria, an initial total of 122 articles were identified. After removing 35 duplicates, the remaining articles underwent a selection process based on their titles and abstracts. This work was carried out by two researchers who worked independently. Subsequently, collective review sessions were conducted to align the criteria and procedures, and all decisions were double-checked by the project director.

A total of 67 articles were excluded for not meeting the criteria, either because they were not empirical studies or they were unrelated to client violence. Ultimately, 20 articles were systematically reviewed.

The data analysis was conducted in two stages: First, each article was independently reviewed and analyzed by two researchers using content analysis. In the second stage, the findings were cross-checked and synthesized collectively to ensure consistency and reliability. Figure 1 describes the procedure.

Figure 1.

Procedure for literature review.

3. Results

The review yielded twenty-two articles, which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Literature review results.

The systematic review included 20 articles analyzing the various realities in different countries: the United States (6), South Africa (3), South Korea (4), Chile (1), Israel (1), Canada (1), Australia (1), Brazil (1), England (2), Turkey (1), Mexico (1), and Italy (1).

Although all the selected articles were related to perceived violence experienced by educational workers, the research themes of the selected papers also referred to levels of teacher victimization, sexual violence, corporal punishment, psychological violence, community violence, help-seeking behavior, and the relationship between violence, stress/burnout, and work engagement.

3.1. Regarding the Presence and Intensity of Violence

The literature review showed that community violence and school violence towards teachers are common. Specifically, the literature indicated that the types of violence towards teachers include physical violence and psychological violence (Bounds & Jenkins, 2016; Çetin et al., 2020; Choi, 2021; Melanda et al., 2021; Moon et al., 2021; Stevenson et al., 2022).

More specifically, the study by Bounds and Jenkins (2016) found that in the United States, obscene comments were the most common form of violence directed at teachers, compared to obscene gestures, bullying, obscene graffiti, damage to personal property, throwing objects, physical attacks, cyberbullying, theft of personal property, and weapon use. These results align with those observed in Australia, where Stevenson et al. (Stevenson et al., 2022) confirmed that 60% of respondents reported verbal assaults, 42% reported physical aggression, and 43% experienced other threatening behaviors from students.

This confirms what Moon and McCluskey (2020) pointed out, that less severe victimizations are the most common (e.g., verbal abuse and aggression without physical contact).

In terms of frequency, the study by Melanda et al. (2018) observed that in Brazil, more than half of teachers reported at least one event of psychological violence.

3.2. Regarding Background Factors or Causes of Violence

Although the studies did not establish causal relationships due to methodological limitations or because it was not the study’s objective, several investigations highlighted certain relationships.

First, numerous studies emphasized the relationship between specific demographic characteristics and victimization. For example, the literature identified that teachers working in urban environments reported more violence than those in suburban or rural areas (Bounds & Jenkins, 2016), as well as teachers with less experience (Çetin et al., 2020).

Regarding gender, a study in Italy observed that women seemed to be more affected by violent behaviors (De Cordova et al., 2019), and in South Africa, it was noted that women, especially young women, felt more unsafe than their male counterparts (Netshitangani, 2019). Similarly, in Turkey, it was confirmed that female teachers were more affected by violence (Çetin et al., 2020). In other contexts, such as the United States, where most studies have been conducted, victimization was not linked to gender, except in that female teachers were more likely to report sexual harassment (Moon et al., 2021).

Thus, while it is not possible to claim that gender causes violence, it can be argued that the phenomenon affects men and women differently.

Regarding other background factors of violence from students and their families, the school climate and its dimensions have been referenced. A relationship has been observed between violence and security, and the community environment, academic environment, and institutional environment dimensions have been referenced (Tarablus & Yablon, 2023). Similarly, interactions, compensation, and autonomy are linked to violence (Kim & Ko, 2022).

In terms of background factors, an interesting finding in South Korea was that corporal punishment by teachers provoked student aggression. This was significant as it described the cyclical nature of violence, with a reciprocal relationship between student aggression and the use of corporal punishment by teachers, rather than positing unidirectional effects (Choi, 2021).

Additionally, it has been observed that a student may commit acts of violence against a teacher if they are aware that there will be no repercussions due to legal and professional expectations regarding teacher behavior (Mangena & Matlala, 2023).

3.3. Regarding Consequences or Effects of Violence

It has been established by Yang et al. (2021) that the vast majority of studies on school violence have focused on its harmful consequences for students. Little evidence exists regarding the effects on teachers, and even less for educational staff in general.

According to the literature, violence negatively affects teachers’ performance (Çetin et al., 2020; Mangena & Matlala, 2023), their resignation and intent to resign (Mangena & Matlala, 2023; Peist et al., 2024; Varela et al., 2021), and stress—through perceived insecurity (Bass et al., 2016; Olivier et al., 2021) and through self-efficacy (Won & Chang, 2020). Consistent with this, the relationship between harassment and violence at work has been shown to negatively impact teachers’ physical and psychological well-being (Mangena & Matlala, 2023).

Emotionally, the literature reports that teachers experienced negative emotions when exposed—both directly and indirectly—to student violence, with frustration being the most common emotion. Fear and anger, social isolation, and general psychological distress were also identified. A positive attitude towards corporal punishment was observed, especially among men. This attitude was followed by thoughts of the negative consequences of punishment and feelings of frustration and anger (Shields et al., 2015).

3.4. Regarding Prevention and/or Coping Strategies

An analysis of the literature confirmed that, as in other social services contexts, studies on violence prevention against educational workers are not reported (Díaz Bórquez et al., 2023). Most of the research included in this review reports on the background and consequences of violence, with only a few addressing coping strategies in response to violence.

Teachers adopted coping strategies at the individual, family, school, and community levels. A series of resilience-associated strategies stood out, such as prayer and seeking support from family and colleagues, but they also employed avoidance strategies, such as emotional withdrawal and avoiding or ignoring difficult students (Maring & Koblinsky, 2013; Martin et al., 2013), particularly adopted by women (Netshitangani, 2019).

In the same vein, it has been reported that teachers are often understanding of young people because they believe low-level violence is part of the job, which makes them reluctant to report it or to perceive students negatively, and they use other social identities to show bravery and gain students’ trust (Martin et al., 2013).

Similarly to the differentiated impact of violence on women, this discrepancy is also observed in coping strategies. In South Africa, female educators reported relying on male teachers to manage incidents of violence in the school (Netshitangani, 2019).

Regarding the effective occurrence of assaults, it was confirmed in the United States that those suffering physical violence tended to report it more than those experiencing theft or damage to personal property, who mainly reported it at the school but not to the police. Their satisfaction with the response depended on whether the students were disciplined (Moon et al., 2021). A similar situation occurred in Israel, where there was an inverse relationship between victimization and willingness to seek help at school, which was stronger among more experienced teachers and those with higher pedagogical competence standards, highlighting the role of status in reporting (Tarablus & Yablon, 2023).

An observational study in a preschool confirmed that the most effective practices for preventing violence were responding to threats by focusing on the student’s needs, self-care, peer and supervisor support, and support from family and friends (Stevenson et al., 2022). The benefits of support were also confirmed by De Cordova et al. (2019), who found that teachers can experience well-being even when subjected to aggressive behaviors, as long as they have the support of leaders and peers.

4. Discussion

The issue of violence in the workplace, particularly within educational contexts, is a global phenomenon recognized as a public health problem with profound effects on both individuals and organizations. In particular, violence from clients has emerged as a significant concern for educational workers (Diaz et al., 2018; Mento et al., 2020; Palma Contreras et al., 2018). The scale of this phenomenon is evident in studies showing that educational workers face not only physical aggression but also psychological and verbal abuse (Moon et al., 2021; Peist et al., 2024).

It is important to note that most research focuses on teachers as the primary victims of violence, neglecting other educational workers, such as assistants, social workers, and administrators. This limitation is significant, as violence in the school environment affects not only teachers but also other key individuals involved in the education and care of students. As highlighted in recent studies, others educational workers also face various forms of violence, pointing to the need for a more inclusive understanding of the phenomenon (Bass et al., 2016; Bounds & Jenkins, 2016). The exclusion of non-teaching employees limits the scope of prevention and intervention policies, reducing the effectiveness of institutional responses to school violence.

In this context, the predominant focus in studies on violence in educational settings has been on coexistence or the “school climate” (Política Nacional de Convivencia Educativa, 2024), which is understood as a set of interactions and relationships among members of the educational community. However, as some studies suggest, this approach has tended to overlook violence against workers as a labor or occupational health issue affecting educational workers. By treating violence as a problem of coexistence rather than a threat to the health and well-being of employees, the potential for implementing effective preventive strategies—such as psychological support programs or organizational structural changes that could mitigate risks for all workers—is limited (Lamothe et al., 2018).

A key observation from the literature is the relationship between the social and organizational context and the prevalence of violence. Studies conducted in various regions (Olivier et al., 2021; Kim & Ko, 2022; Bass et al., 2016) suggest that factors such as school climate, leadership, and perceptions of safety and the community environment are strongly associated with the risk of violence. In this sense, the importance of creating a safer work environment is highlighted—not only in physical terms but also concerning workers’ perceptions of their well-being and institutional support.

Moreover, violence in educational settings does not manifest uniformly across all contexts. Studies have shown significant variations by country and type of educational institution, emphasizing the importance of contextualizing research. For example, in the United States and Australia, there is a high incidence of verbal and physical assaults, particularly between students and teachers (Bounds & Jenkins, 2016; Stevenson et al., 2022). However, in countries like South Africa, violence is deeply influenced by gender dynamics and socioeconomic contexts, where women—especially young women—feel more insecure and exposed to violence (Netshitangani, 2019). Similarly, studies in Turkey and Brazil indicate that psychological violence, such as mobbing, has a significant impact on teachers’ well-being and performance, affecting women and less experienced professionals the most (Çetin et al., 2020; Melanda et al., 2021).

5. Conclusions

Workplace violence in the educational field is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that affects both teachers and non-teaching staff, including assistants, social workers, and administrators. This initial review has identified the prevalence of physical, psychological, and verbal assaults in various educational contexts, highlighting the need for a more inclusive understanding of the phenomenon.

However, it is important to recognize the limitations of this study, especially concerning the languages and the omission of certain contexts in the existing literature. Most of the reviewed studies come from Anglo-Saxon contexts, which may limit the generalization of results to other cultural and educational realities. Additionally, the lack of research in languages other than English and in other specific contexts may have left significant gaps in the global understanding of this problem. Furthermore, studies focusing on non-teaching educational staff remain limited, highlighting an ongoing need for broader, more inclusive research.

To advance the understanding of workplace violence in the educational field, it is recommended to develop research focusing on the identification and evaluation of effective prevention strategies, tailored to the particularities of each educational environment.

In conclusion, workplace violence in the educational field requires urgent attention and a comprehensive response involving all educational stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.-O. and D.D.-B.; methodology, M.C.-O., D.D.-B. and P.C.; validation, M.C.-O.; formal analysis, M.C.-O. and P.C.; investigation, M.C.-O. and D.D.-B.; resources, M.C.-O. and D.D.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.-O. and P.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C.-O. and D.D.-B.; project administration, M.C.-O.; funding acquisition, M.C.-O. and D.D.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by Mutual de Seguridad with Social Security resources from Law No. 16,744 on Work Accidents and Occupational Health. The APC was founded by Mutual de Seguridad with Social Security resources from Law No. 16,744 on Work Accidents and Occupational Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | People working in schools have been referred to in various ways in the literature. In this study, the term ’educational workers’ will be used to refer inclusively to both teachers and school employees in educational support roles, such as special education teachers, instructional assistants, library media specialists, counselors, school psychologists, speech therapists, administrators, nurses, custodians, cafeteria staff, and office personnel. |

References

- Baker-Henningham, H., Scott, Y., Bowers, M., & Francis, T. (2019). Evaluation of a violence-prevention programme with jamaican primary school teachers: A cluster randomised trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B. I., Cigularov, K. P., Chen, P. Y., Henry, K. L., Tomazic, R. G., & Li, Y. (2016). The effects of student violence against school employees on employee burnout and work engagement: The roles of perceived school unsafety and transformational leadership. International Journal of Stress Management, 23(3), 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., López, V., Bilbao, M., & Ascorra, P. (2019). Victimization of teachers by students in Israel and in Chile and its relations with teachers’ victimization of students. Aggressive Behavior, 45(2), 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bounds, C., & Jenkins, L. N. (2016). Teacher-directed violence in relation to social support and work stress. Contemporary School Psychology, 20(4), 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B. (2021). Cycle of violence in schools: Longitudinal reciprocal relationship between student’s aggression and teacher’s use of corporal punishment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), 1168–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, Z., Özözen Danacı, M., & Kuzu, A. (2020). The effect of psychological violence on preschool teachers’ perceptions of their performance. South African Journal of Education, 40(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cordova, F., Berlanda, S., Pedrazza, M., & Fraizzoli, M. (2019). Violence at School and the well-being of teachers. The importance of positive relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, X., Mauro Cardarelli, A., Villarroel Poblete, C., Toro Cifuentes, J. P., & Campos Schwarze, D. (2018). Elaboración y validación de un instrumento para la medición de la violencia laboral externa y sus factores de riesgo en población de trabajadores y trabajadoras chileno/as. Ciencia & Trabajo, 20(62), 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Berr, X., Cardarelli, A. M., Pablo, J., Cifuentes, T., Poblete, C. V., & Schwarze, D. C. (2015). Validación del inventario de violencia y acoso psicológico en el trabajo—IVAPT-PANDO—En tres ámbitos laborales chilenos. Available online: www.cienciaytrabajo.cl (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Díaz Bórquez, D., Calderón-Orellana, M., Inostroza Correa, A., & Varas González, G. (2023). Client violence towards childcare workers: A systematic literature review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 2023, 5556520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A., & Birchall, J. (2023). Student violence towards teaching assistants in UK schools: A case of gender-based violence. Gender and Education, 35(1), 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Ko, Y. (2022). Perceived discrimination and workplace violence among school health teachers: Relationship with school organizational climate. Journal of Korean Academy of Community Health Nursing, 33(4), 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamothe, J., Couvrette, A., Lebrun, G., Yale, G., Roy, C., Guay, S., & Geoffrion, S. (2018). Violence against child protection workers: A study of workers’ experiences, attributions, and coping strategies. Child Abuse and Neglect, 81, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., Badenes-Ribera, L., Martinez, A., & McMahon, S. D. (2019). Prevalence of student violence against teachers: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 9(6), 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N., Di Stasio, E., Capitanelli, I., Lops, E. A., Chirico, F., & Garbarino, S. (2019). Sleep problems and workplace violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangena, M. C., & Matlala, S. F. (2023). Teachers’ lived experiences of workplace violence and harassment committed by learners from selected high schools in Limpopo province, South Africa. Healthcare, 11(18), 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maring, E. F., & Koblinsky, S. A. (2013). Teachers’ challenges, strategies, and support needs in schools affected by community violence: A qualitative study. Journal of School Health, 83(6), 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D., Mackenzie, N., & Healy, J. (2013). Balancing risk and professional identity, secondary school teachers’ narratives of violence. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 13(4), 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Usarralde, M. J., Gil-Salom, D., & Macías-Mendoza, D. (2019). Revisión sistemática de responsabilidad social universitaria y aprendizaje servicio: Análisis para su institucionalización. Revista Mexicana de Investigacion Educativa, 24(80), 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Melanda, F. N., Dos Santos, H. G., Salvagioni, D. A. J., Mesas, A. E., Gonzàlez, A. D., & De Andrade, S. M. (2018). Physical violence against schoolteachers: An analysis using structural equation models. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 34(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanda, F. N., Salvagioni, D. A. J., Mesas, A. E., González, A. D., & de Andrade, S. M. (2021). Recurrence of violence against teachers: Two-year follow-up study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17–18), NP9757–NP9776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mento, C., Silvestri, M. C., Bruno, A., Muscatello, M. R. A., Cedro, C., Pandolfo, G., & Zoccali, R. A. (2020). Workplace violence against healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 51, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B., & McCluskey, J. (2020). An exploratory study of violence and aggression against teachers in middle and high schools: Prevalence, predictors, and negative consequences. Journal of School Violence, 19(2), 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B., Morash, M., & McCluskey, J. (2021). Student violence directed against teachers: Victimized teachers’ reports to school officials and satisfaction with school responses. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(13–14), NP7264–NP7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netshitangani, T. (2019). Voices of teachers on school violence and gender in South African urban public schools. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, 8, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH. (2020). Types of workplace violence. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/WPVHC/Nurses/Course/Slide/Unit1_5 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Notelaers, G., & Einarsen, S. (2013). The world turns at 33 and 45: Defining simple cutoff scores for the Negative Acts Questionnaire–Revised in a representative sample. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(6), 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E., Janosz, M., Morin, A. J. S., Archambault, I., Geoffrion, S., Pascal, S., Goulet, J., Marchand, A., & Pagani, L. S. (2021). Chronic and temporary exposure to student violence predicts emotional exhaustion in high school teachers. Journal of School Violence, 20(2), 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma Contreras, A., Ahumada Muñoz, M., & Ansoleaga Moreno, E. (2018). How do Chilean workers cope with the workplace violence? Psicoperspectivas, 17(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peist, E., McMahon, S. D., Davis-Wright, J. O., & Keys, C. B. (2024). Understanding teacher-directed violence and related turnover through a school climate framework. Psychology in the Schools, 61(1), 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Política Nacional de Convivencia Educativa. (2024). Available online: https://convivenciaparaciudadania.mineduc.cl/convivencia-escolar/ (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Schofield, K. E., Ryan, A. D., & Stroinski, C. (2022). Risk factors for occupational injuries in schools among educators and support staff. Journal of Safety Research, 80, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultes, M. T., Stefanek, E., van de Schoot, R., Strohmeier, D., & Spiel, C. (2015). Measuring implementation of a school-based violence prevention program. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 222(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, N., Nadasen, K., & Hanneke, C. (2015). Teacher responses to school violence in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Applied Social Science, 9(1), 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicora, A., Nothdurfter, U., Rosina, B., & Sanfelici, M. (2022). Service user violence against social workers in Italy: Prevalence and characteristics of the phenomenon. Journal of Social Work, 22(1), 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D. J., Neill, J. T., Ball, K., Smith, R., & Shores, M. C. (2022). How do preschool to year 6 educators prevent and cope with occupational violence from students? Australian Journal of Education, 66(2), 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarablus, T., & Yablon, Y. B. (2023). Teachers’ willingness to seek help for violence against them: The moderating effect of teachers’ seniority. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(19–20), 10703–10722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J. J., Melipillán, R., González, C., Letelier, P., Massis, M. C., & Wash, N. (2021). Community and school violence as significant risk factors for school climate and bonding of teachers in Chile: A national hierarchical multilevel analysis. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(1), 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.-D., & Chang, E. J. (2020). The relationship between school violence-related stress and quality of life in school teachers through coping self-efficacy and job satisfaction. School Mental Health, 12(1), 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Qin, L., & Ning, L. (2021). School violence and teacher professional engagement: A cross-national study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 628809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).