Abstract

This article develops dual variational formulations for a large class of models in variational optimization. The results are established through basic tools of functional analysis, convex analysis and duality theory. The main duality principle is developed as an application to a Ginzburg–Landau-type system in superconductivity in the absence of a magnetic field. In the first section, we develop new general dual convex variational formulations, more specifically, dual formulations with a large region of convexity around the critical points, which are suitable for the non-convex optimization for a large class of models in physics and engineering. Finally, in the last section, we present some numerical results concerning the generalized method of lines applied to a Ginzburg–Landau-type equation.

MSC:

49N15; 65N40

1. Introduction

In this section, we establish a dual formulation for a large class of models in non-convex optimization.

The main duality principle is applied to the Ginzburg–Landau system in superconductivity in the absence of a magnetic field.

Such results are based on the works of J.J. Telega and W.R. Bielski [1,2,3,4] and on a D.C. optimization approach developed in Toland [5].

About the other references, details on the Sobolev spaces involved are found in [6]. Related results on convex analysis and duality theory are addressed in [7,8,9,10]. Finally, similar models on the superconductivity physics may be found in [11,12].

Remark 1.

It is worth highlighting that we may generically denote

simply by

where denotes a concerning identity operator.

Other similar notations may be used along this text as their indicated meaning are sufficiently clear.

Additionally, denotes the Laplace operator, and for real constants and , the notation means that is much larger than

Finally, we adopt the standard Einstein convention of summing up repeated indices, unless otherwise indicated.

In order to clarify the notation, here, we introduce the definition of topological dual space.

Definition 1

(Topological dual spaces). Let U be a Banach space. We define its dual topological space as the set of all linear continuous functionals defined on U. We suppose that such a dual space of U may be represented by another Banach space , through a bilinear form (here, we are referring to standard representations of dual spaces of Sobolev and Lebesgue spaces). Thus, given linear and continuous, we assume the existence of a unique such that

The norm of f, denoted by , is defined as

At this point, we start to describe the primal and dual variational formulations.

Let be an open, bounded, connected set with a regular (Lipschitzian) boundary denoted by

First, we emphasize that, for the Banach space , we have

For the primal formulation, we consider the functional , where

Here, we assume , , . Moreover, we denote

Define also by

by

and by

where

It is worth highlighting that in such a case,

Furthermore, define the following specific polar functionals specified, namely, by

by

if , where

At this point, we give more details about this calculation.

Observe that

Defining we have so that

where are solution of equations (optimality conditions for such a quadratic optimization problem)

and

and therefore,

and

Substituting such results into (7), we obtain

if

Finally, is defined by

Define also

by

and by

2. The Main Duality Principle, a Convex Dual Formulation, and the Concerning Proximal Primal Functional

Our main result is summarized by the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

Considering the definitions and statements in the last section, suppose also that is such that

Under such hypotheses, we have

and

Proof.

Since

from the variation in , we obtain

so that

From the variation in , we obtain

From the variation in , we also obtain

and therefore,

From the variation in u, we have

and, thus,

Finally, from the variation in , we obtain

so that

that is,

From such results and , we have

so that

Additionally, from this and from the Legendre transform proprieties, we have

and thus, we obtain

Summarizing, we have

On the other hand,

Finally, by a simple computation, we may obtain the Hessian

in , so that we may infer that is concave in in .

3. A Primal Dual Variational Formulation

In this section, we develop a more general primal dual variational formulation suitable for a large class of models in non-convex optimization.

Consider again , and let and be three times Fréchet differentiable functionals. Let be defined by

Assume that is such that

and

Denote , define by

Denoting and , define also

for an appropriate to be specified.

Observe that in , the Hessian of is given by

Observe also that

and

Define now

so that

From this, we may infer that and

Moreover, for sufficiently big, is convex in a neighborhood of .

Therefore, in the last lines, we have proven the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

Under the statements and definitions of the last lines, there exist and such that

and is such that

Moreover, is convex in

4. One More Duality Principle and a Concerning Primal Dual Variational Formulation

In this section, we establish a new duality principle and a related primal dual formulation.

The results are based on the approach of Toland [5].

4.1. Introduction

Let be an open, bounded, connected set with a regular (Lipschitzian) boundary denoted by

Let be a functional such that

where .

Suppose are both three times Fréchet differentiable convex functionals such that

and

Assume also that there exists such that

Moreover, suppose that if is such that

then

At this point, we define by

where

Observe that so that

On the other hand, clearly, we have

so that we have

Let .

Since J is strongly continuous, there exist and such that

From this, considering that is convex on V, we may infer that is continuous at u,

Hence, is strongly lower semi-continuous on V, and since is convex, we may infer that is weakly lower semi-continuous on V.

Let be a sequence such that

Hence,

Suppose that there exists a subsequence of such that

From the hypothesis, we have

which contradicts

Therefore, there exists such that

Since V is reflexive, from this and the Katutani Theorem, there exists a subsequence of and such that

Consequently, from this and considering that is weakly lower semi-continuous, we have

so that

Define by

and

Defining also by

from the results in [5], we may obtain

so that

Suppose now that there exists such that

From the standard necessary conditions, we have

so that

Define now

From these last two equations, we obtain

From such results and the Legendre transform properties, we have

so that

and

so that

4.2. The Main Duality Principle and a Related Primal Dual Variational Formulation

Considering these last statements and results, we may prove the following theorem.

Theorem 3.

Let be an open, bounded, connected set with a regular (Lipschitzian) boundary denoted by

Let be a functional such that

where .

Suppose are both three times Fréchet differentiable functionals such that there exists such that

and

Assume also that there exists and such that

Assume that is such that

Define

Assume that is such that if , then

Suppose also

Define by

and

Define also by

and

Observe that since is such that

we have

Let be a small constant.

Define

Under such hypotheses, defining by

we have

Proof.

Observe that from the hypotheses, and the results and statements of the last subsection,

where

Moreover, we have

Additionally, from hypotheses and the results in the last subsection,

so that clearly, we have

From these results, we may infer that

The proof is complete. □

Remark 2.

At this point, we highlight that has a large region of convexity around the optimal point , for sufficiently large and corresponding sufficiently small.

Indeed, observe that for ,

where is such that

Taking the variation in in this last equation, we obtain

so that

From this, we have

On the other hand, from the implicit function theorem,

so that

and

Similarly, we may obtain

and

Denoting

and

we have

and

From this, we have

about the optimal point

5. A Convex Dual Variational Formulation

In this section, again for , an open, bounded, connected set with a regular (Lipschitzian) boundary , and , we denote , and by

and

We define also

and and by

and

if , where

for some small real parameter and where denotes a concerning identity operator.

Finally, we also define

Assuming

by directly computing , we may obtain that for such specified real constants, is convex in and it is concave in on

Considering such statements and definitions, we may prove the following theorem.

Theorem 4.

Let be such that

and be such that

Under such hypotheses, we have

so that

Proof.

Observe that so that, since is convex in and concave in on , we obtain

Now, we show that

From

we have

and thus,

From

we obtain

and thus,

Finally, denoting

from

we have

so that

Observe now that

so that

The solution for this last system of Equations (30) and (31) is obtained through the relations

and

so that

and

and hence, from the concerning convexity in u on V,

Moreover, from the Legendre transform properties

so that

Joining the pieces, we have

The proof is complete. □

Remark 3.

We could have also defined

for some small real parameter . In this case, is positive definite, whereas in the previous case, is negative definite.

6. Another Convex Dual Variational Formulation

In this section, again for , an open, bounded, connected set with a regular (Lipschitzian) boundary , and , we denote , and by

and

We define also

and and by

and

At this point, we define

where

and

Finally, we also define

and by

Moreover, assume

By directly computing , we may obtain that for such specified real constants, is concave in on

Indeed, recalling that

and

we obtain

in and

in .

Considering such statements and definitions, we may prove the following theorem.

Theorem 5.

Let be such that

and be such that

Under such hypotheses, we have

so that

Proof.

Observe that so that, since is concave in on , and is quadratic in , we have

Consequently, from this and the Min–Max Theorem, we obtain

Now, we show that

From

we have

and thus

Finally, denoting

from

we have

so that

Observe now that

so that

The solution for this last equation is obtained through the relation

so that from this and (39), we have

Thus,

and

and hence, from the concerning convexity in u on V,

Moreover, from the Legendre transform properties

so that

Joining the pieces, we have

The proof is complete. □

7. A Related Numerical Computation through the Generalized Method of Lines

In the next few lines, we present some improvements concerning the initial conception of the generalized method of lines, originally published in the book entitled “Topics on Functional Analysis, Calculus of Variations and Duality” [9], 2011.

Concerning such a method, other important results may be found in articles and books such as [7,9,13].

Specifically about the improvement previously mentioned, we have changed the way we truncate the series solution obtained through an application of the Banach fixed point theorem to find the relation between two adjacent lines. The results obtained are very good even as a typical parameter is very small.

In the next few lines and sections, we develop in details such a numerical procedure.

7.1. About a Concerning Improvement to the Generalized Method of Lines

Let , where

Consider the problem of solving the partial differential equation

Here,

, and

In a partial finite differences scheme (about the standard finite differences method, please see [14]), such a system stands for

with the boundary conditions

and

Here, N is the number of lines and

In particular, for , we have

so that

We solve this last equation through the Banach fixed point theorem, obtaining as a function of

Indeed, we may set

and

Thus, we may obtain

Similarly, for , we have

We solve this last equation through the Banach fixed point theorem, obtaining as a function of and

Indeed, we may set

and

Thus, we may obtain

Now reasoning inductively, having

we may obtain

We solve this last equation through the Banach fixed point theorem, obtaining as a function of and

Indeed, we may set

and

Thus, we may obtain

We have obtained ,

In particular, so that we may obtain

Similarly,

an so on, until the following is obtained:

The problem is then approximately solved.

7.2. Software in Mathematica for Solving Such an Equation

We recall that the equation to be solved is a Ginzburg–Landau-type one, where

Here,

, and In a partial finite differences scheme, such a system stands for

with the boundary conditions

and

Here, N is the number of lines and

At this point, we present the concerning software for an approximate solution.

Such a software is for (10 lines) and .

*************************************

- ;

- ;

- ; (

- ;

- ;

- ;

- ;

- ];

*************************************

The numerical expressions for the solutions of the concerning lines are given by

7.3. Some Plots Concerning the Numerical Results

In this section, we present the lines related to results obtained in the last section.

Indeed, we present such mentioned lines, in a first step, for the previous results obtained through the generalized of lines and, in a second step, through a numerical method, which is combination of the Newton one and the generalized method of lines. In a third step, we also present the graphs by considering the expression of the lines as those also obtained through the generalized method of lines, up to the numerical coefficients for each function term, which are obtained by the numerical optimization of the functional J, specified below. We consider the case in which and .

For the procedure mentioned above as the third step, recalling that lines, considering that , we may approximately assume the following general line expressions:

Defining

and

we obtain by numerically minimizing J.

Hence, we have obtained the following lines for these cases. For such graphs, we have considered 300 nodes in x, with as units in

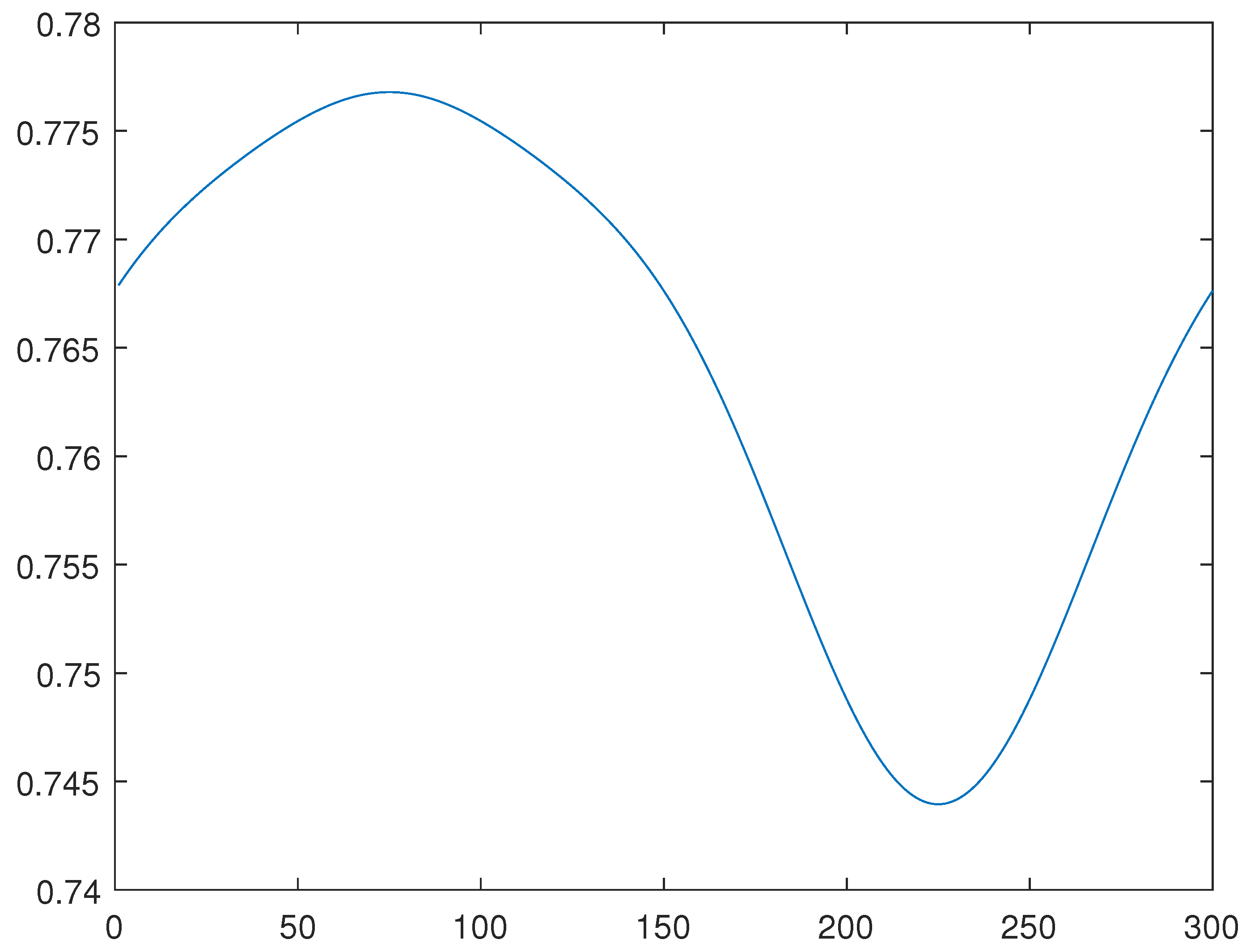

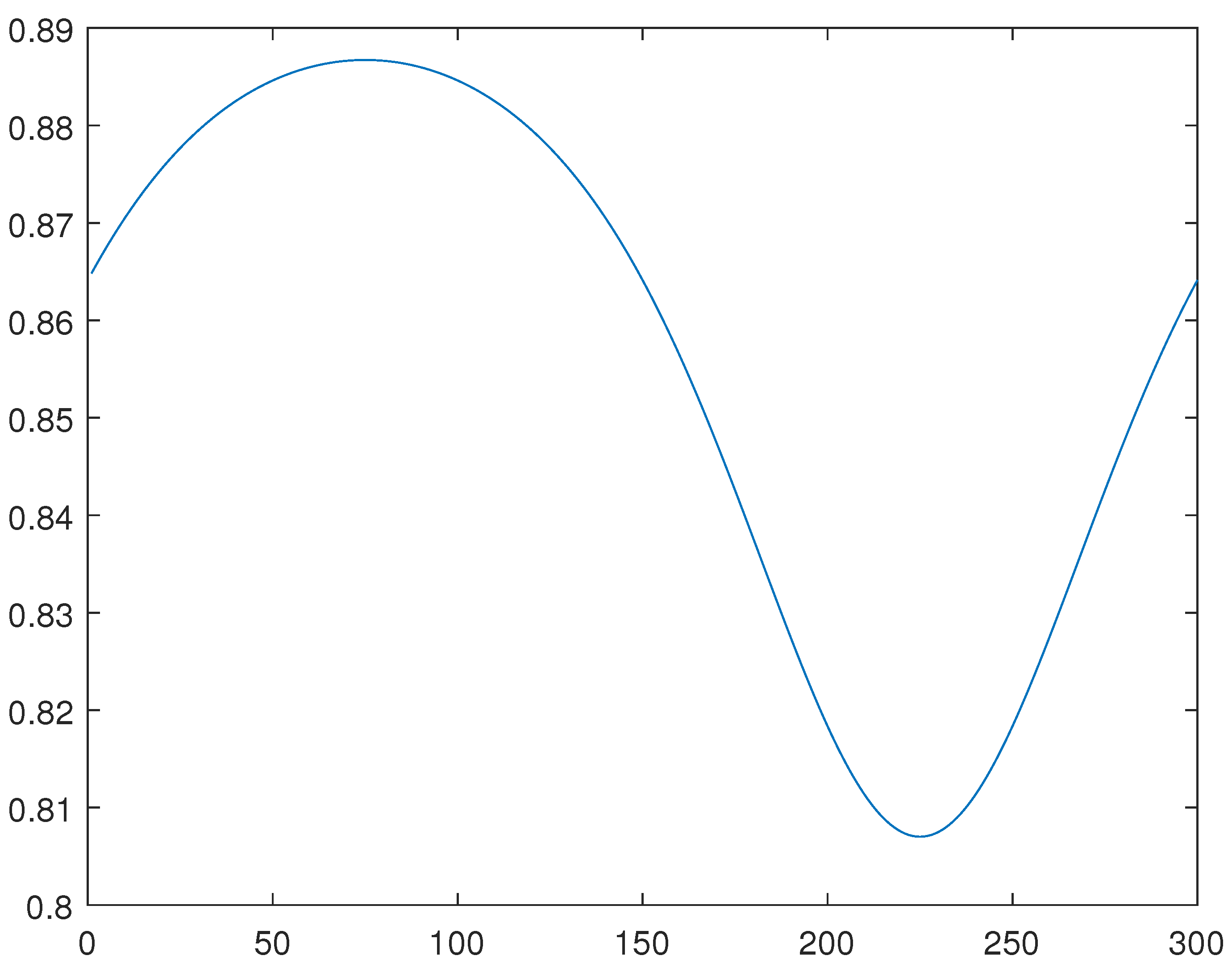

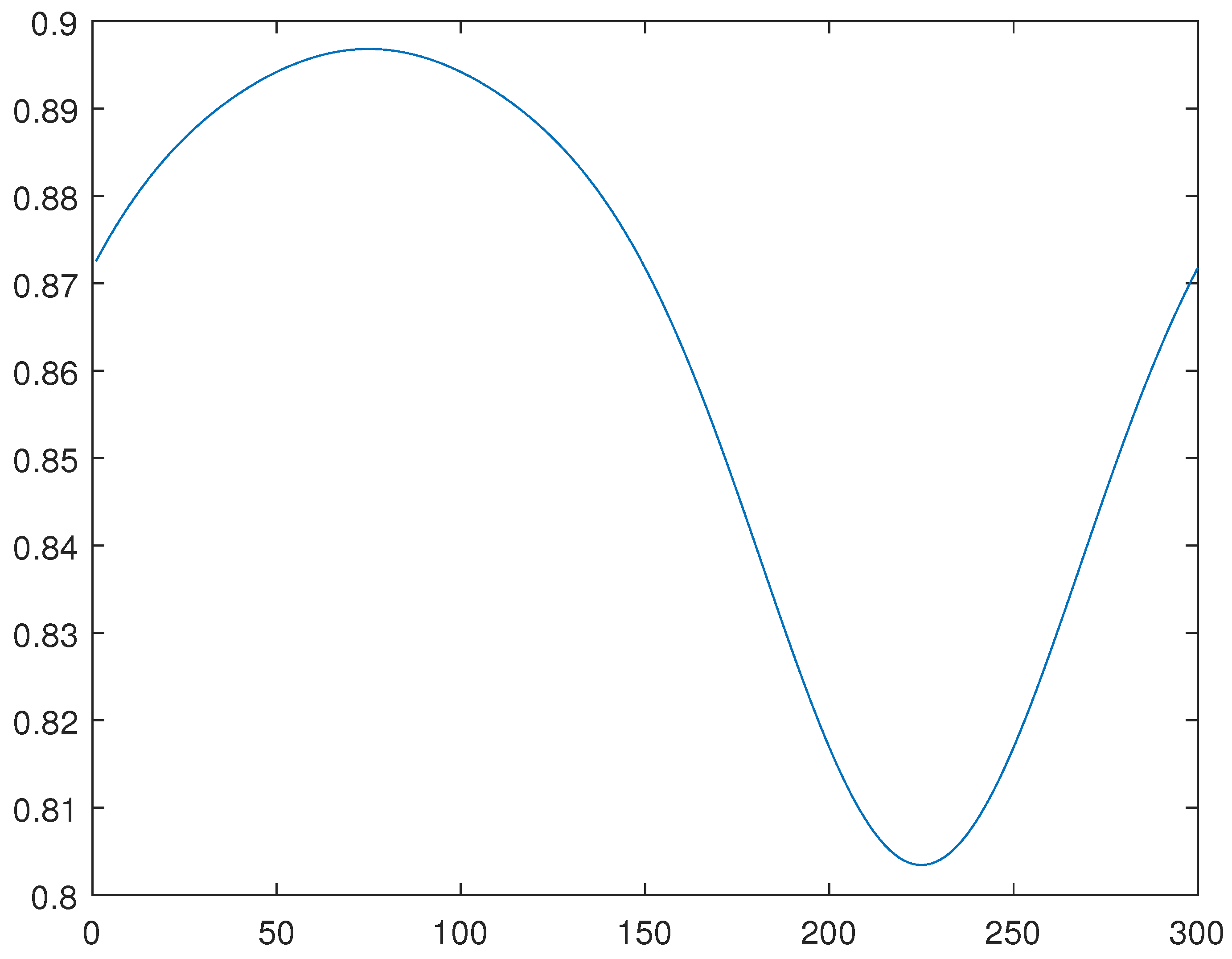

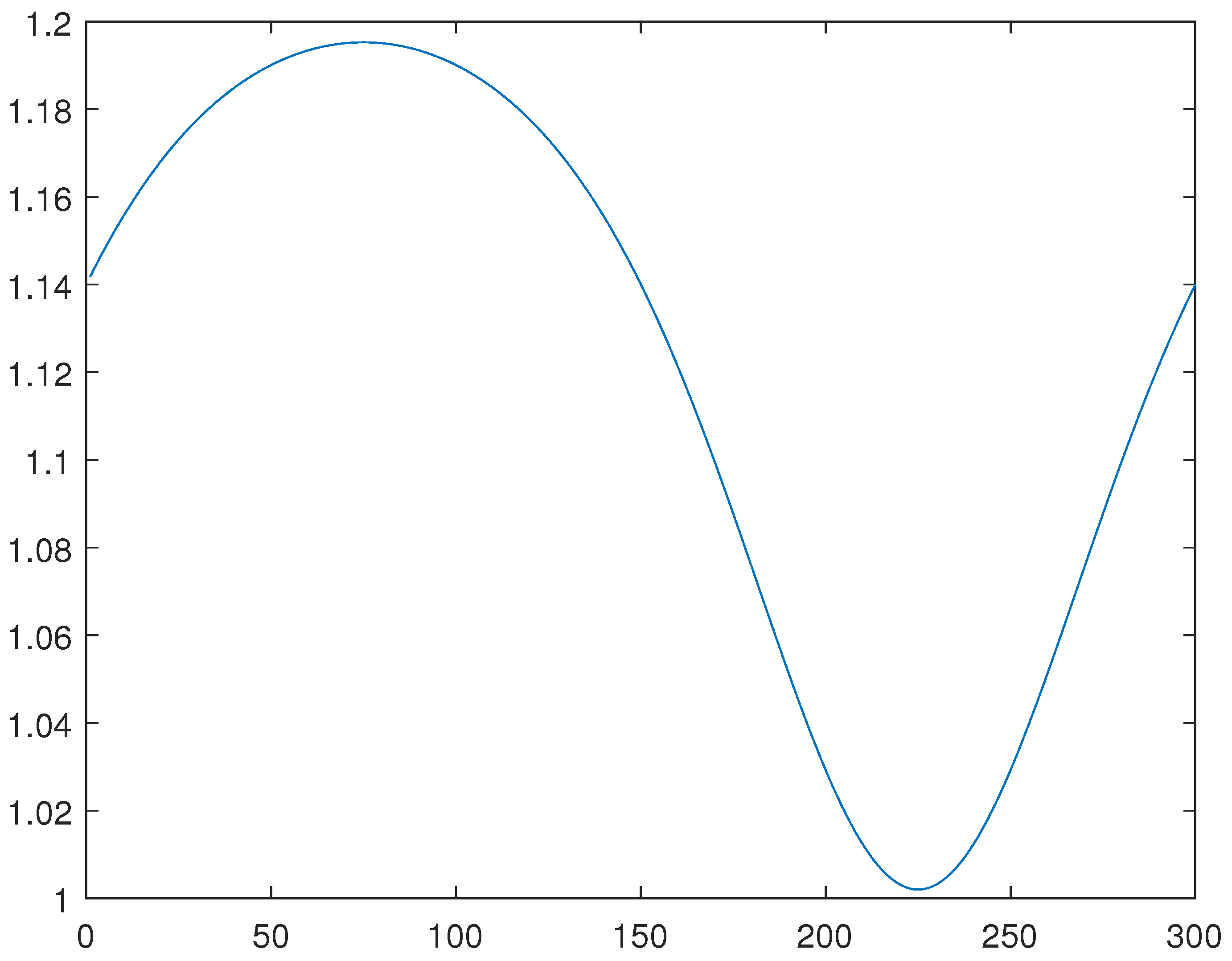

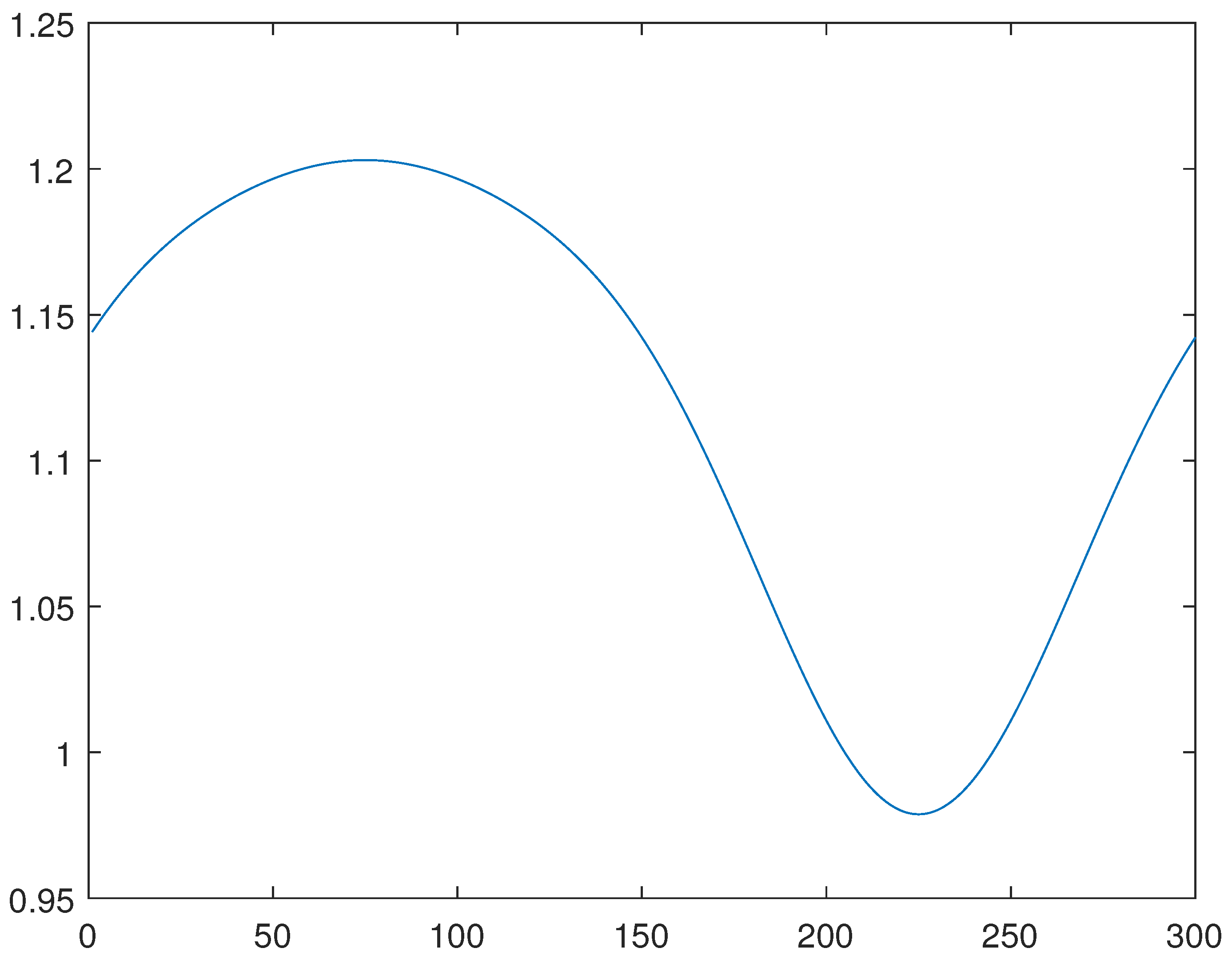

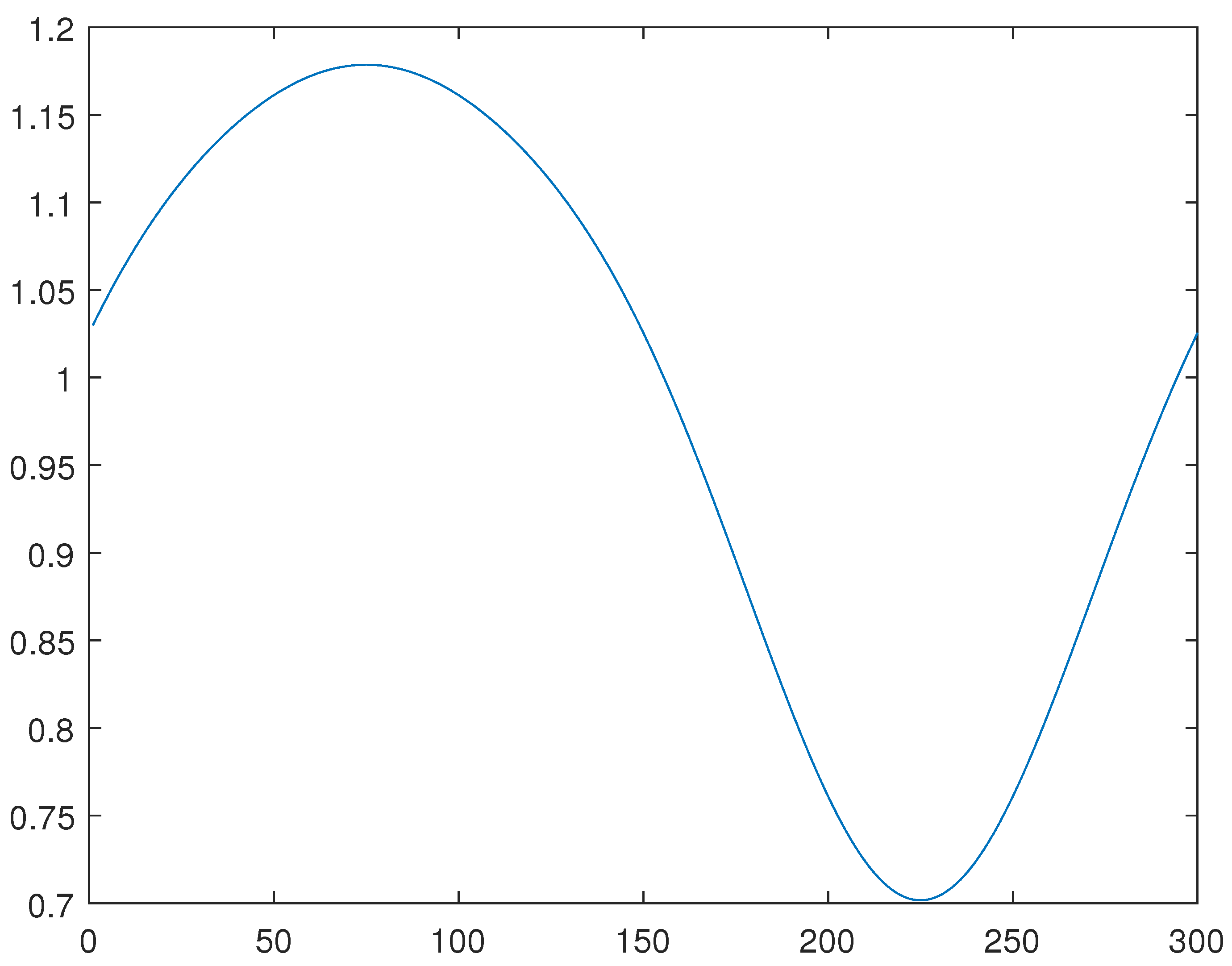

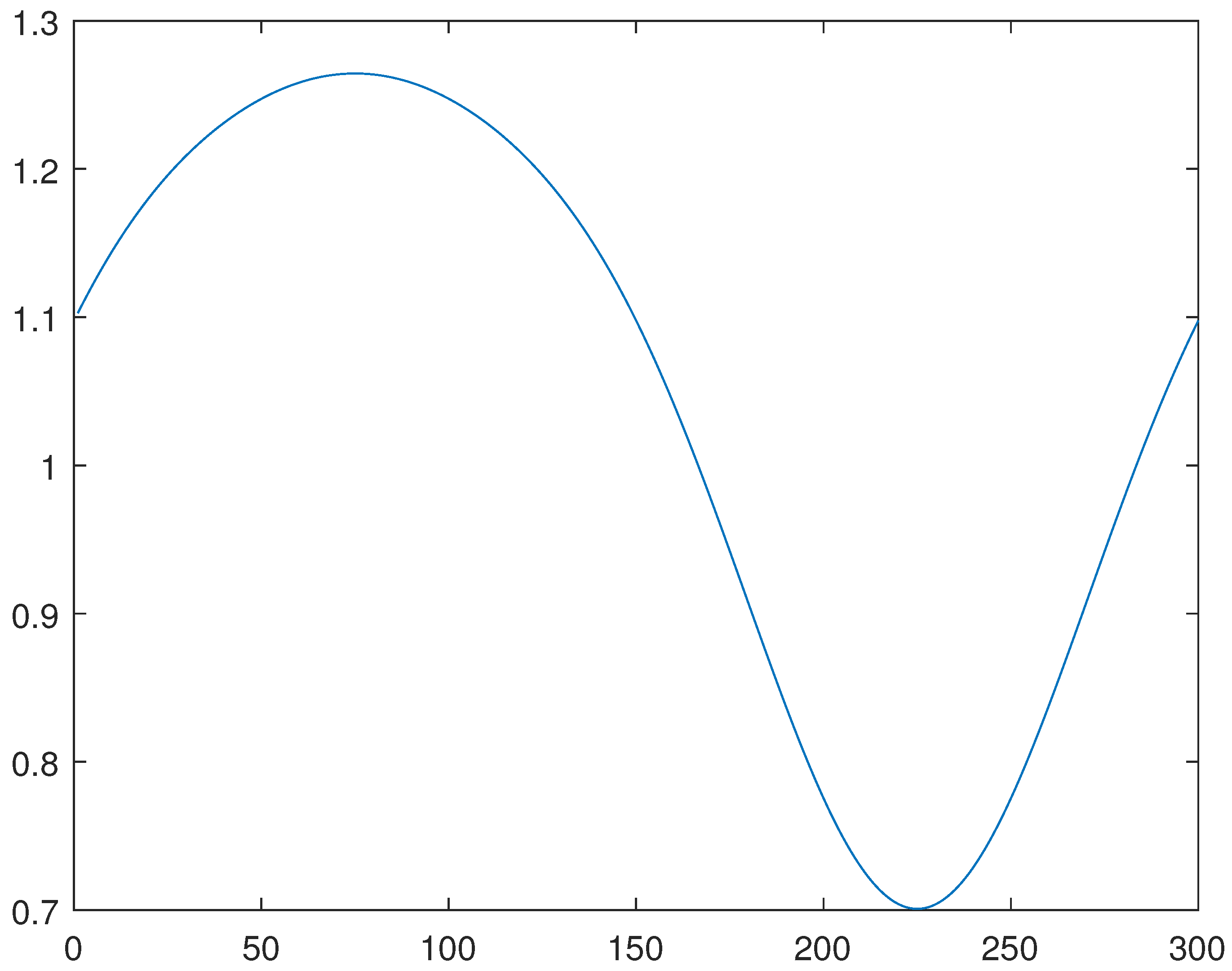

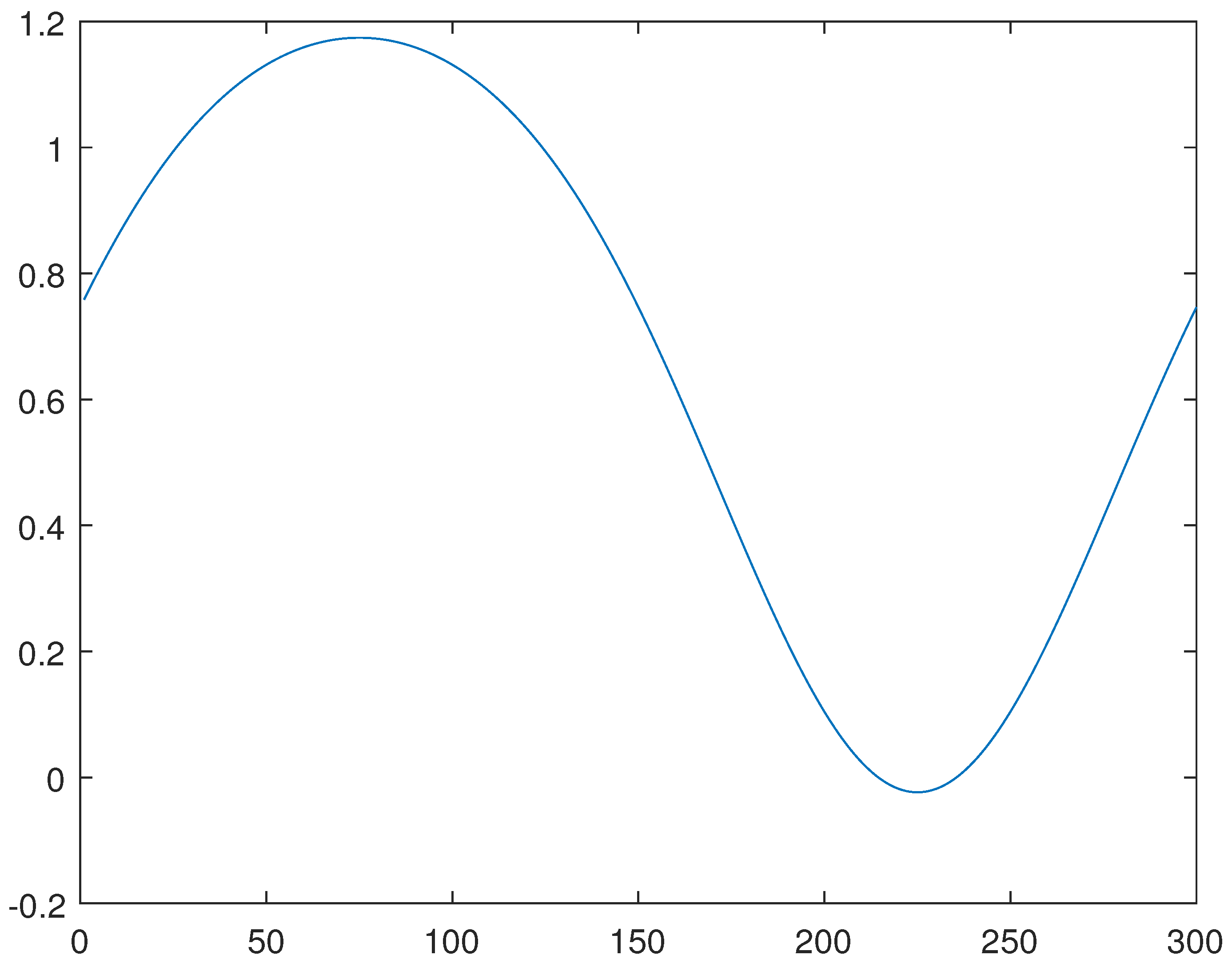

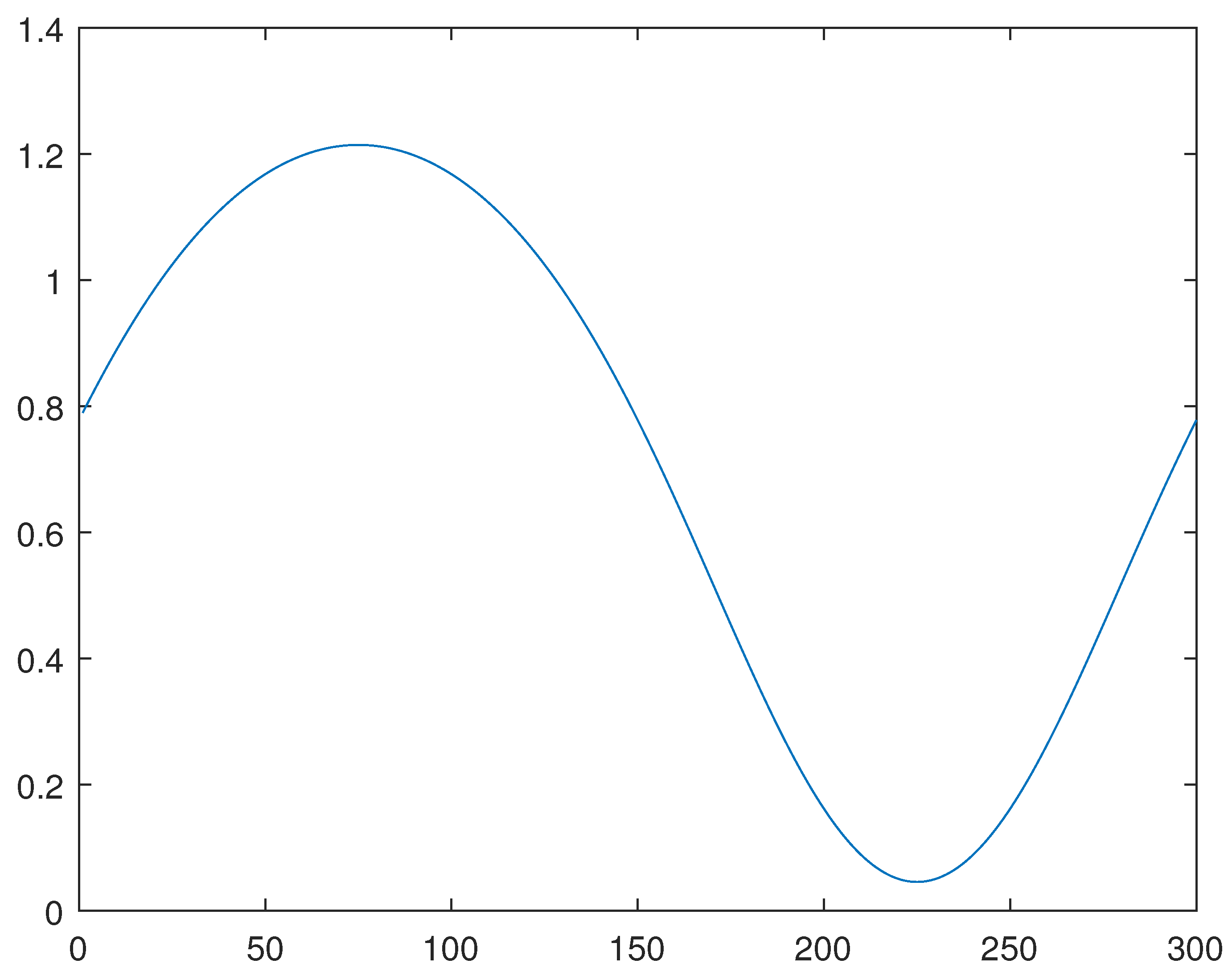

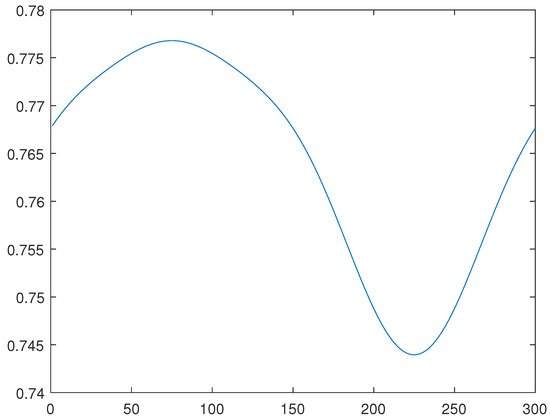

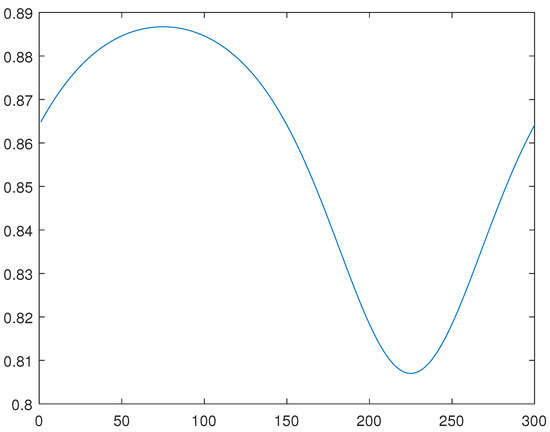

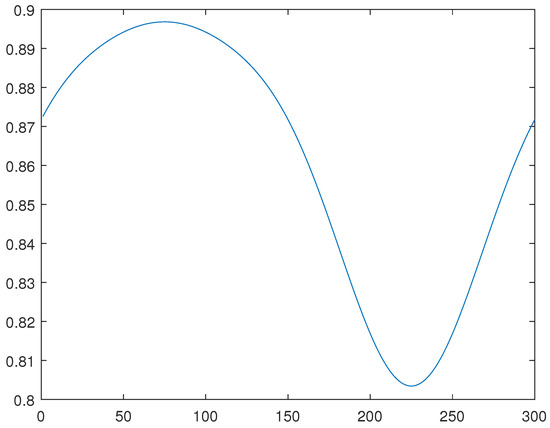

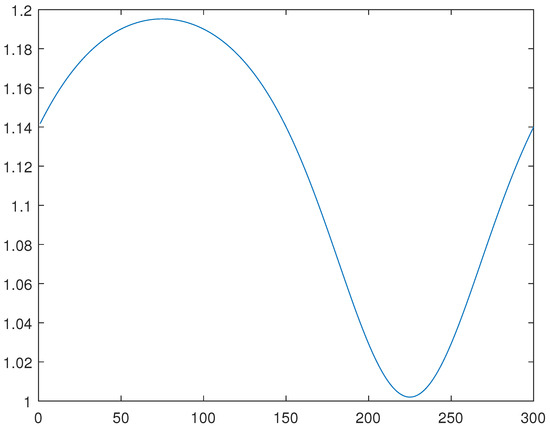

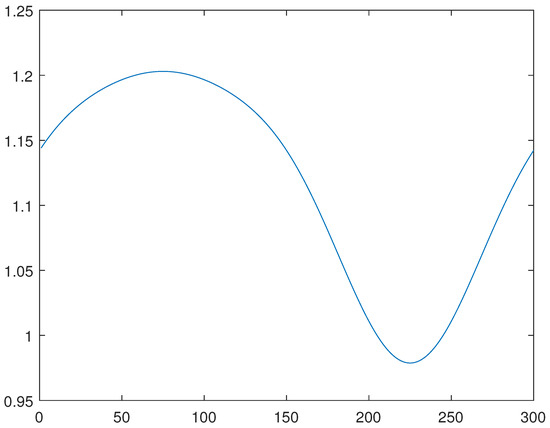

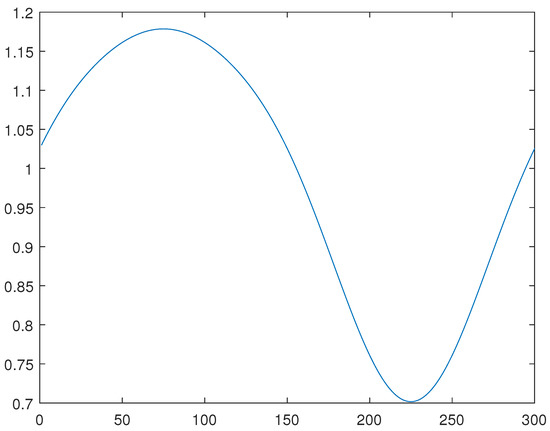

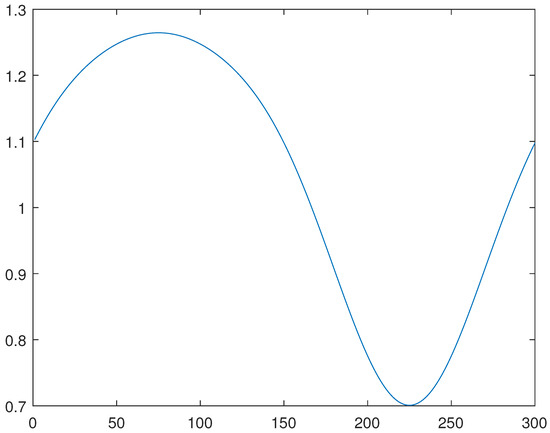

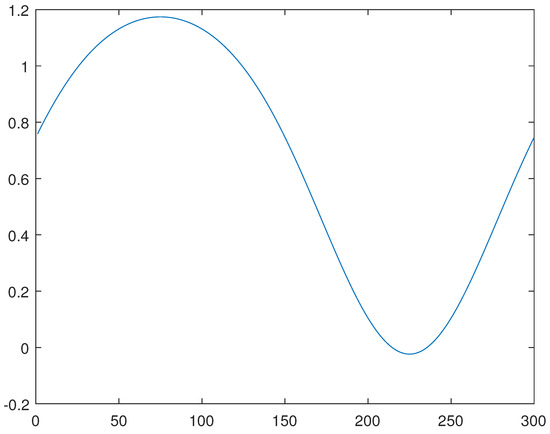

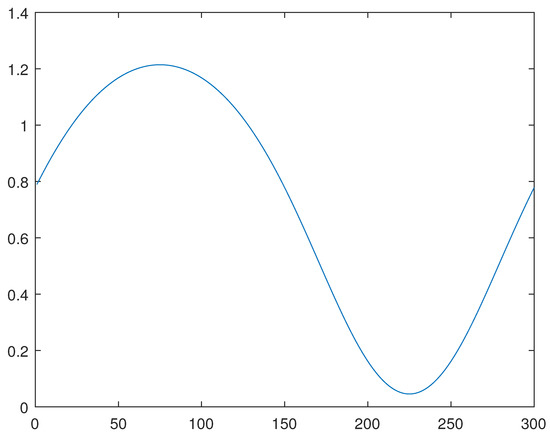

For the line 2, please see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, obtained through the generalized method of lines, through a combination of the Newton and generalized methods of lines, and through the minimization of the functional J, respectively.

Figure 1.

Line 2, solution through the general method of lines.

Figure 2.

Line 2, solution through Newton’s Method.

Figure 3.

Line 2, solution through the minimization of functional J.

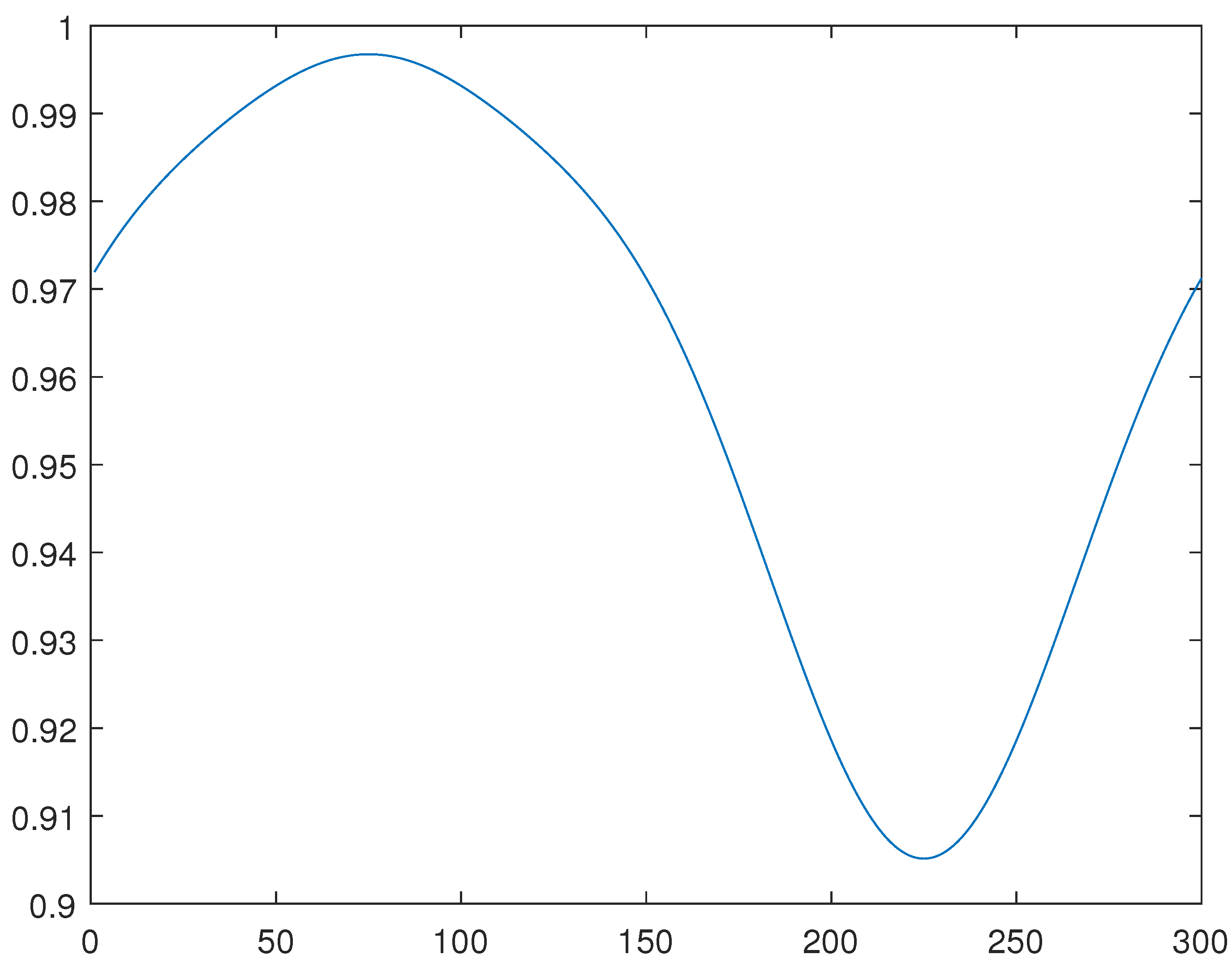

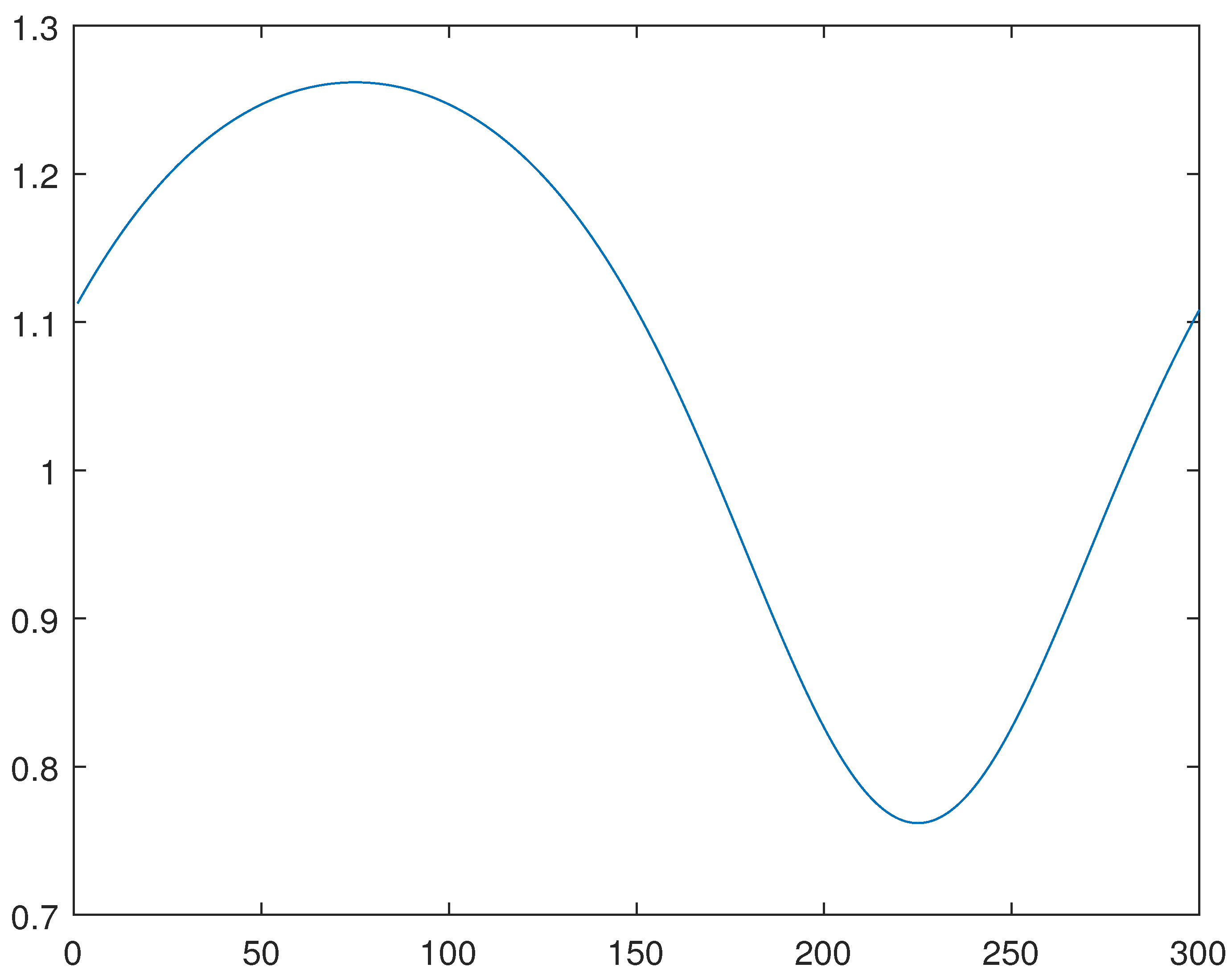

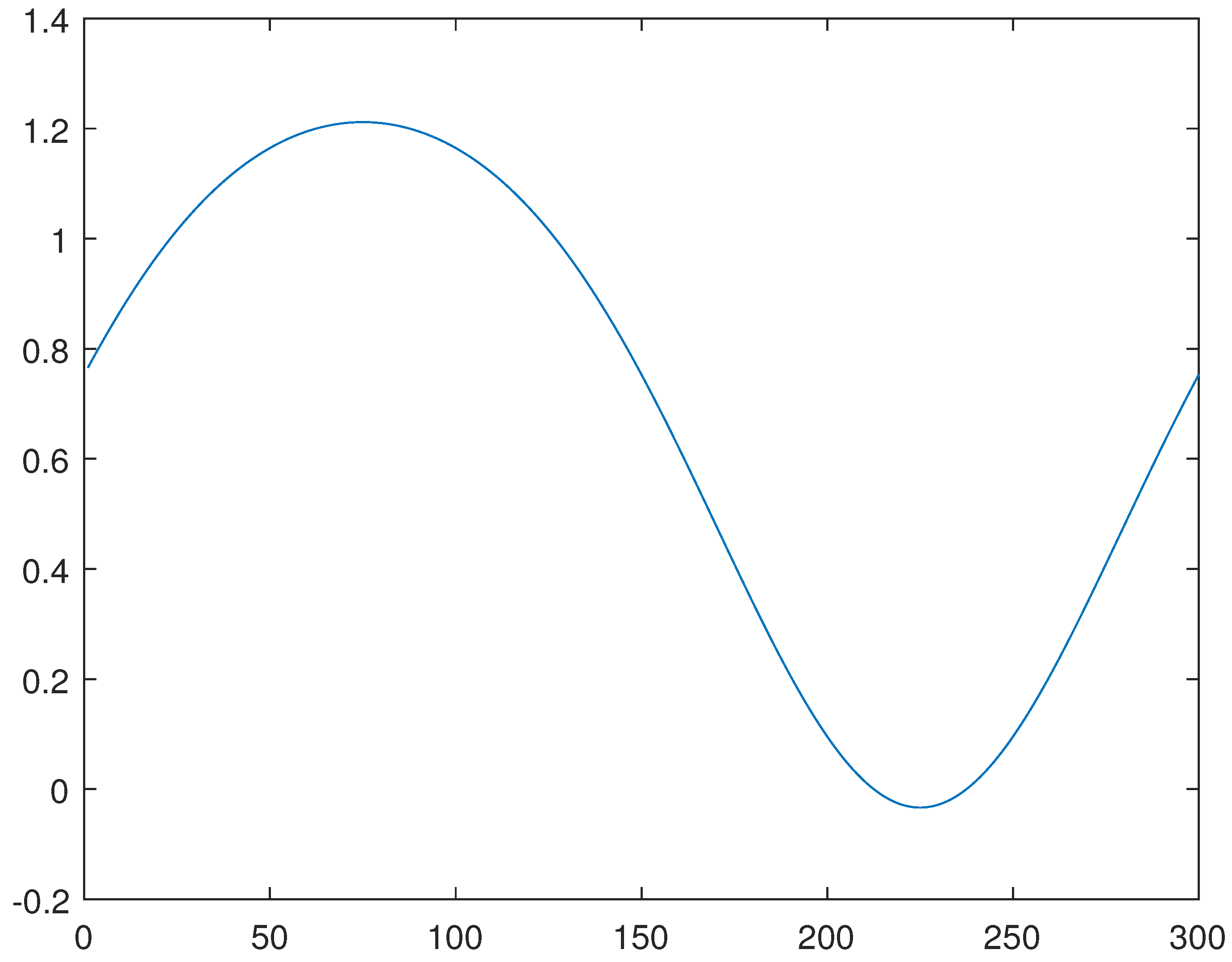

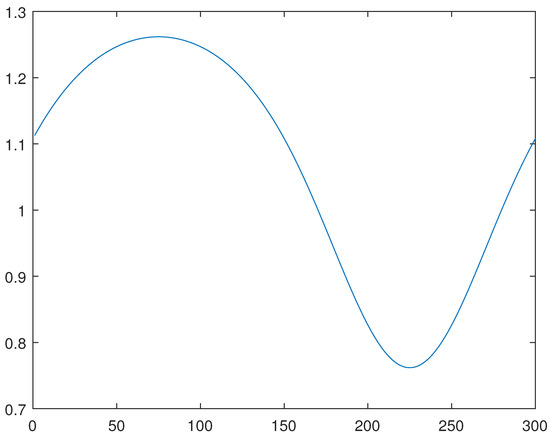

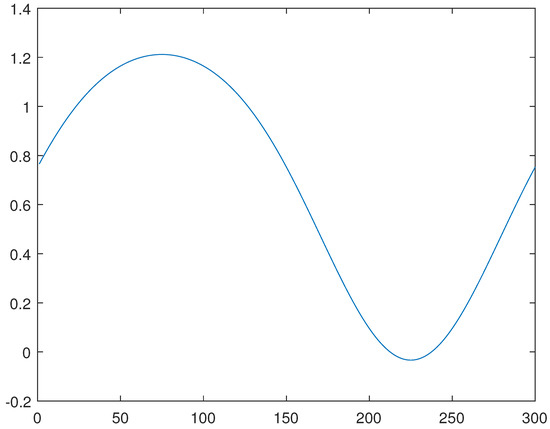

For the line 4, please see Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, obtained through the generalized method of lines, through a combination of the Newton and generalized methods of lines, and through the minimization of the functional J, respectively.

Figure 4.

Line 4, solution through the general method of lines.

Figure 5.

Line 4, solution through Newton’s Method.

Figure 6.

Line 4, solution through the minimization of functional J.

For the line 6, please see Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, obtained through the generalized method of lines, through a combination of the Newton and generalized methods of lines, and through the minimization of the functional J, respectively.

Figure 7.

Line 6, solution through the general method of lines.

Figure 8.

Line 6, solution through Newton’s Method.

Figure 9.

Line 6, solution through the minimization of functional J.

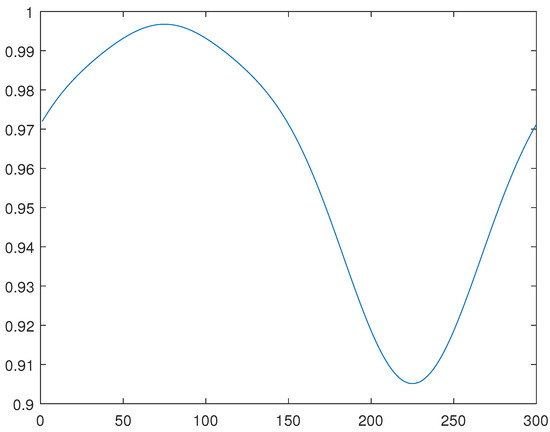

For the line 8, please see Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, obtained through the generalized method of lines, through a combination of the Newton and generalized methods of lines, and through the minimization of the functional J, respectively.

Figure 10.

Line 8, solution through the general method of lines.

Figure 11.

Line 8, solution through Newton’s Method.

Figure 12.

Line 8, solution through the minimization of functional J.

8. Conclusions

In the first part of this article, we developed duality principles for non-convex variational optimization. In the following sections, we proposed dual convex formulations suitable for a large class of models in physics and engineering. In the previous section, we presented an advance concerning the computation of a solution for a partial differential equation through the generalized method of lines. In particular, in its previous versions, we used to truncate the series in ; however, we have realized that the results are much better when taking line solutions in series for and its derivatives, as is indicated in the present software.

This is a small difference from the previous procedure but results in great improvements as the parameter is small.

Indeed, with a sufficiently large N (number of lines), we may obtain very good qualitative results even as is very small.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bielski, W.R.; Galka, A.; Telega, J.J. The Complementary Energy Principle and Duality for Geometrically Nonlinear Elastic Shells. I. Simple case of moderate rotations around a tangent to the middle surface. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 1988, 38, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bielski, W.R.; Telega, J.J. A Contribution to Contact Problems for a Class of Solids and Structures. Arch. Mech. 1985, 37, 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Telega, J.J. On the Complementary Energy Principle in Non-Linear Elasticity. Part I: Von Karman Plates and Three Dimensional Solids. C.R. Acad. Sci. Paris Ser. II 1989, 308, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Galka, A.; Telega, J.J. Duality and the Complementary Energy Principle for a Class of Geometrically Non-Linear Structures. Part I. Five parameter shell model; Part II. Anomalous dual variational priciples for compressed elastic beams. Arch. Mech. 1995, 47, 677–724. [Google Scholar]

- Toland, J.F. A duality principle for non-convex optimisation and the calculus of variations. Arch. Rat. Mech. Anal. 1979, 71, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.A.; Fournier, J.F. Sobolev Spaces, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Botelho, F.S. Functional Analysis, Calculus of Variations and Numerical Methods in Physics and Engineering; CRC Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Botelho, F.S. Variational Convex Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Botelho, F. Topics on Functional Analysis, Calculus of Variations and Duality; Academic Publications: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rockafellar, R.T. Convex Analysis; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Annet, J.F. Superconductivity, Superfluids and Condensates, 2nd ed.; Oxford Master Series in Condensed Matter Physics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifschits, E.M. Course of Theoretical Physics; Volume 5—Statistical Physics, Part 1; Butterworth-Heinemann; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Botelho, F. Existence of solution for the Ginzburg-Landau system, a related optimal control problem and its computation by the generalized method of lines. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 218, 11976–11989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strikwerda, J.C. Finite Difference Schemes and Partial Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).