Abstract

The patent serves as a vital component of scientific text, and over time, escalating competition has generated a substantial demand for patent analysis encompassing areas such as company strategy and legal services, necessitating fast, accurate, and easily applicable similarity estimators. At present, conducting natural language processing(NLP) on patent content, including titles, abstracts, etc., can serve as an effective method for estimating similarity. However, the traditional NLP approach has some disadvantages, such as the requirement for a huge amount of labeled data and poor explanation of deep-learning-based model internals, exacerbated by the high compression of patent content. On the other hand, most knowledge-based deep learning models require a vast amount of additional analysis results as training variables in similarity estimation, which are limited due to human participation in the analysis part. Thus, in this research, addressing these challenges, we introduce a novel estimator to enhance the transparency of similarity estimation. This approach integrates a patent’s content with international patent classification (IPC), leveraging bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT), and non-negative matrix factorization (NMF). By integrating these techniques, we aim to improve knowledge discovery transparency in NLP across various IPC dimensions and incorporate more background knowledge into context similarity estimation. The experimental results demonstrate that our model is reliable, explainable, highly accurate, and practically usable.

Keywords:

patent similarity; bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT); non-negative matrix factorization; natural language processing; auto-encoder model MSC:

68T50

1. Introduction

The scientific literature plays a crucial role in advancing scientific knowledge, with patents being among the most valuable assets in this endeavor. In such scenarios, the scrutiny and analysis of patent texts, recognized as a powerful tool aiding inventors in securing market exclusivity for new inventions, play a crucial role in economic globalization and intense competition, according to Abbas et al. [1]. In response to this demand, researchers worldwide have devised various methodologies for patent text analysis, involving titles, abstracts, inventors, international patent classification (IPC) codes, and other patent contents. Traditionally, researchers assess similarity by narrowing the scope of patent analysis through strategies like tracking patents from the same research lab, group, or company, as these are likely to share commonalities, and then proceed with manual analysis of the narrowed documents. Another common approach involves fixing a specific field, refining the related patent area, manually selecting key content (like words or phrases), and then estimating similarity based on the frequency of these elements. Regrettably, conducting this type of traditional analysis demands specialized expertise, which limits its widespread application. While this process functions effectively in numerous fields such as social science, company strategies, and industry analysis, the vast volume of patents today makes such analysis impractical. In the study by Saad et al. [2], this escalating volume of patent information has rendered patent search and analysis tasks crucial from both legal and managerial standpoints. Additionally, the lack of objectivity in traditional methods, where most research relies on manual analysis to estimate similarity at the end, results in poor rigor. Therefore, a fast, robust, and explainable method for estimating patent similarity is essential, especially for tasks such as knowledge discovery, information extraction, and recommending similar patents.

In the past few years, while integrating natural language processing (NLP) into patent text analysis has shown promise, the complexity and high compression of patent content often render traditional NLP methods, such as term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) and object–action–objection phrase matching, inadequate. This is because NLP-based similarity estimation models operate on the assumption that similar content shares identical or related words within the same field, but the highly compressed nature of patents, which rarely share such words and require significant manual effort to establish word similarity indexes, often causes this assumption to fail. Recently, unlike traditional NLP models, rich, efficient, and flexible deep-learning-based models in natural language semantic analysis have emerged as integral components in estimating natural language similarity. For instance, in the research by Jia et al. [3], a text augmentation technique based on contrastive learning representation models was devised to classify text. However, the effectiveness of these models, particularly for patent similarity analysis, is limited by the substantial need for training data, which is especially challenging with supervised methods, as most researchers struggle to gather large amounts of labeled data. In summary, the integration of unsupervised NLP models is essential for analyzing patent texts, and ensuring model transparency or explainability is equally critical for accurately estimating patent similarity.

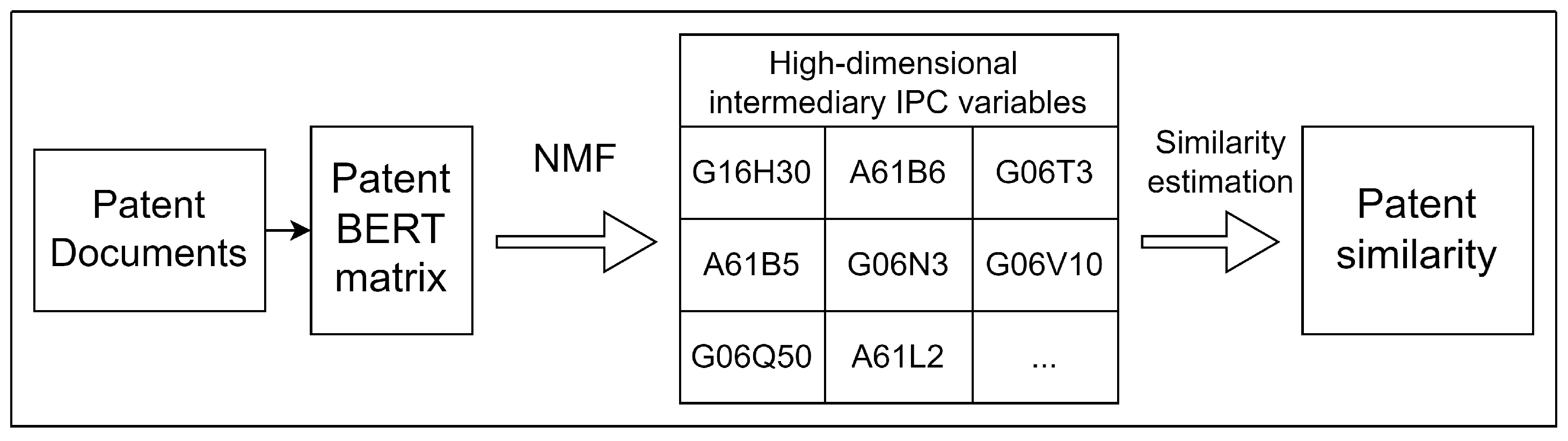

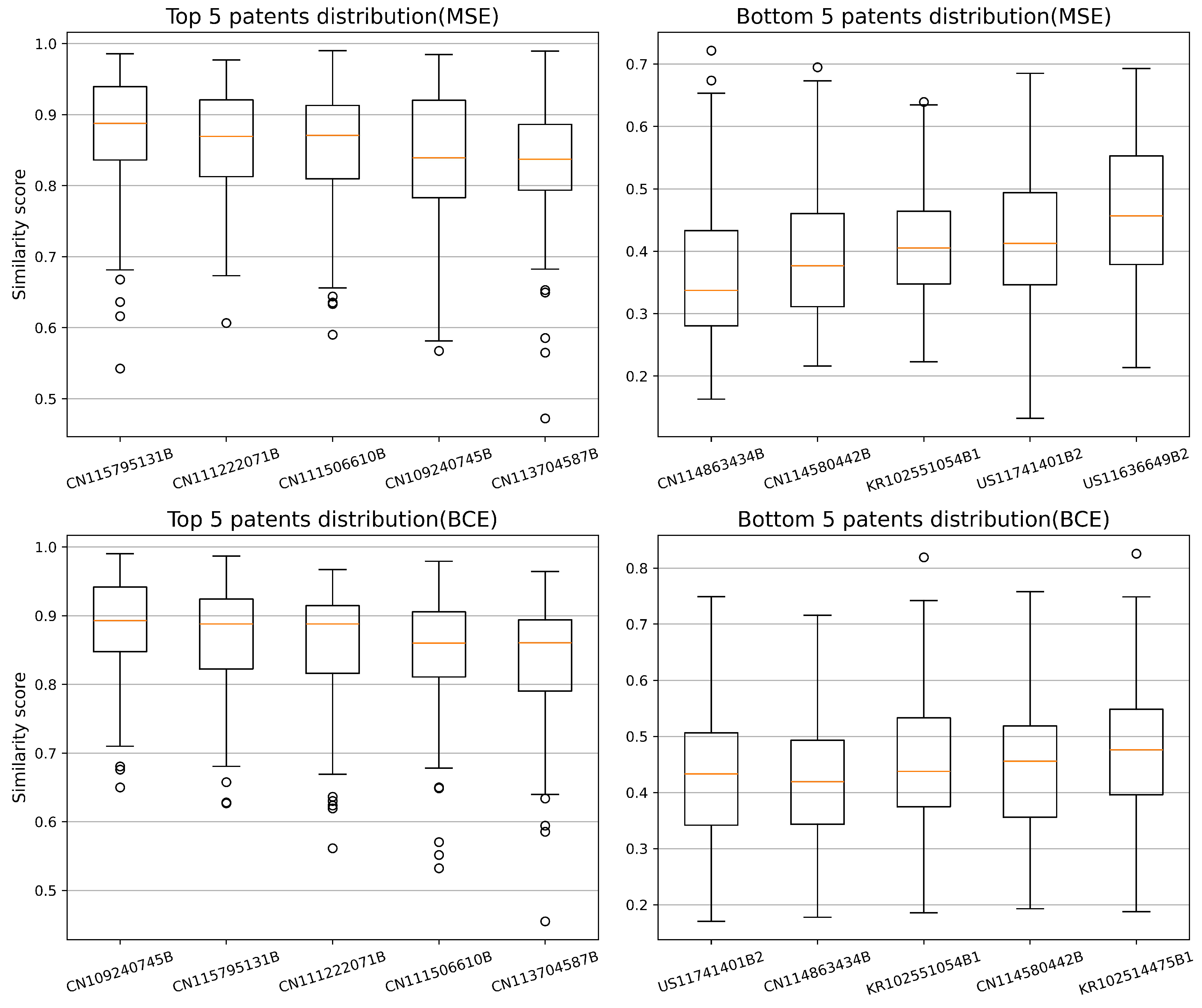

Currently, the most widely used unsupervised deep-learning-based NLP model in semantic analysis is bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT), which aids computers in comprehending the meaning of ambiguous language in text by leveraging surrounding text to establish context. Unlike traditional NLP methods that process text sequentially in a single direction, BERT uses a bidirectional approach for context vectorization, capturing both the left and right contexts of a word simultaneously, allowing for easy conversion of short natural language content into fixed-length vectors. For instance, a BERT model known as the ’BERT-Large-model’ developed by Devlin et al. [4] can transform text content with a length of fewer than 512 tokens into a vector of size 1024. Compared to traditional deep-learning-based NLP algorithms, BERT offers greater transparency, but interpreting its full numerical output requires a higher level of scientific expertise and explainability. To address this, this paper introduces a novel method that enhances transparency by integrating information from the abstract content and IPC of a given patent. This approach creatively merges BERT variables with patent IPC categories, resulting in a series of intermediary variables, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Streamline processes of patent similarity estimation.

In this research, IPC was chosen as an intermediary variable because a patent document can belong to one or more categories, making it useful for searching and locating related patents. Traditionally, IPC categories have been used to estimate similarity by treating each category as background information and representing the patent as their intersection, so that the similarity between two patents is based on the similarity of their IPC vectors, similar to the approach used in the research by Liang et al. [5]. Although this method is swift, its results are often disputed due to the limited information it considers, yet it underscores the crucial role IPC plays as a standard feature in similarity estimation. Another reason that IPC was chosen is based on the study conducted by Jung et al. [6]. After analyzing patent datasets from the World Intellectual Property Organization, which included data from over 100 countries in 2021, IPC demonstrated significant performance in patent classification. The abstract was selected because, for most researchers, only four components of a patent’s natural language text are easily accessible: the title, abstract, inventors, and claims. Among these, the title and inventors offer limited information, and the claims are often templated, with patents from the same company or organization sometimes sharing nearly identical basic claims.

Presently, here are two main approaches to address the challenge of merging a patent’s BERT output with IPC. One approach combines IPC with the latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) BERT model, using LDA to identify a set number of topics within the document content and then distributing patent documents based on these topics, which are subsequently merged with the mean value of the one-hot encoded IPC. The other approach directly incorporates the one-hot encoded IPC into the scaled patent’s BERT output. Both approaches have significant drawbacks: the first is constrained by a limited number of topics, which affects similarity estimation and causes the mean IPC value in each category to often approach zero, while the second, despite being technically functional, suffers from unreliable results due to IPC variability. Hence, instead of directly merging BERT and IPC variables into a single matrix, non-negative matrix factorization (where , with A representing the document-BERT information matrix, W representing the document-IPC matrix, and H representing the IPC-encoder matrix) was applied to the BERT matrix to generate an IPC-based multi-dimensional intermediary variable matrix and estimate similarity thereafter. The detailed framework and formulas for our patent similarity estimation model are outlined in the Section 3 while a comparison is presented and discussed in the Section 5.

2. Related Work

2.1. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers

Bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) is a deep learning pre-processing model first introduced in the research by Devlin et al. [4]. According to the authors, the pre-trained BERT model generates deep bidirectional representations, alleviating the necessity for many heavily engineered task-specific architectures. Similar to the traditional TF-IDF model, BERT can be employed across various NLP domains, diverse languages, and projects related to natural language processing. For instance, in the study by Müller et al. [7], they developed a pre-trained BERT model named COVID-Twitter-BERT (CT-BERT), which can be applied to various natural language processing tasks related to COVID-19, including classification, question answering, and chatbots. In the study by Kim et al. [8], BERT was applied to the medical context using a state-of-the-art Korean language model, leading to a significant increase in the accuracy of next-sentence prediction. In the research conducted by Chan et al. [9], BERT was employed in predicting crowdfunding outcomes. They observed that crowdfunding projects with a higher average BERT score in the story section description tended to raise more funding than those with lower average BERT scores. In the study by Licari et al. [10], BERT was applied to legal tasks such as legal research, document synthesis, contract analysis, argument extraction, and legal prediction based on Italian legal data. Likewise, in other research discussed in the article by Kumar et al. [11], BERT was employed to extract and consolidate information from the body of literature regarding approaches to managing the end-of-life of plastics.

2.2. Non-Negative Matrix Factorization

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF), also known as non-negative matrix approximation, is an algorithm for decomposing a non-negative matrix A into two smaller non-negative matrices W and H such that . In natural language analysis, NMF finds extensive application in topic or knowledge discovery. For instance, in the study by Shahbazi et al. [12], NMF is incorporated into a deep learning reinforcement model along with semantics-assisted non-negative matrix factorization. This integration is utilized to extract meaningful and underlying topics from short document contents. In the work presented by Khan et al. [13], a novel recommender systems framework is introduced, which relies on a semantics-based content embedding model for items. This model is enriched by contextual features extracted through an NMF-based collaborative filtering convolutional neural network. In the research conducted by Xiaohui et al. [14], key topics are extracted from short text content using NMF and a correlation matrix. Additionally, in the study by Xu et al. [15], a novel implicit aspect identification approach is proposed based on NMF. Apart from knowledge discovery, NMF has been widely utilized for text dimension reduction. In the research by Suri et al. [16], a comparison between LDA and NMF is presented, showing that NMF outperformed LDA in topic detection using textual data collected from Twitter and RSS news feeds. In the research conducted by Habbat et al. [17], LDA outperforms NMF in terms of topic coherence when applied to a dataset of Moroccan tweets. Another similar study conducted by Zoya et al. [18] demonstrates that LDA yielded better performance in analyzing Urdu tweets. Furthermore, in the domain of natural language processing, NMF is frequently applied to document factorization. For instance, Luo et al. [19] employ non-negative tensor factorization to cluster patients based on atomic features (such as words in clinical narrative text) and simultaneously identify latent groups of higher-order features linked to patient clusters.

2.3. Text Similarity Estimation and Semantic Analysis

Currently, the most traditional, classic, and common method for estimating the similarity between two natural language documents is the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF). The main idea behind TF-IDF is that documents sharing common words are likely to describe similar topics. However, over time, TF-IDF has encountered increasing challenges. Variations in document length often lead to varying amounts of useful tokenized words, causing instability in patent similarity calculations. Additionally, the limited number of related documents might introduce significant bias in similarity estimation through traditional NLP methods, potentially yielding subjective and inaccurate results when background knowledge is lacking.

To tackle this challenge, semantic analysis, particularly natural language feature extraction, plays a crucial role. For instance, in the study conducted by Pudasaini et al. [20], they introduced an NLP pipeline integrating techniques such as document classification, segmentation, and text extraction to derive structured information from textual documents. In the research by Jiansong et al. [21], they proposed a semantic, rule-based NLP approach for automated information extraction from construction regulatory documents. The study by Olivetti et al. [22] demonstrates the advantage of NLP semantic analysis methods in materials science, particularly in extracting additional information beyond text contained in figures and tables within related textual content. Other research by Kim et al. [23] demonstrates the significant advantage of supervised keyword extraction algorithms in summarizing informative text and reducing intensive time consumption in the analysis of bio information text content, where they utilize a deep learning model for NLP to extract keywords from pathology reports using biomedical vocabulary sets. In the paper written by Fan et al. [24], a novel neural network model is introduced, incorporating an attention mechanism network and a convolutional neural network to enhance semantic analysis performance. In the research by Li et al. [25], they proposed a word segmentation method for Chinese chemical literature based on a hybrid feature fusion learning model in the Chinese chemical science corpus to enhance semantic analysis in Chinese text content. Presently, for a clear and objective semantic analysis of natural language content, extracting and matching specific phrase patterns like subject–action–object (SAO) are deemed effective methods for estimating similarity. This approach entails converting unstructured textual data into structured textual data, integrating subjects, actions, and objects. This method has been widely applied in various projects, such as representing the significance of technological features in Alzheimer’s disease by Li et al. [26], detecting potential research and development partners by Xuefeng et al. [27], and identifying the direction of technological change by Junfang et al. [28]. In addition to semantic analysis on the limited natural language text content, enriching the content of the given documents with extra information can be another efficient method. In other words, when comparing the similarity between two patents, it is advantageous to consider not only their title or abstract but also include external data from the same or similar text content. For instance, in the study conducted by Islam et al. [29], they incorporate additional semantic word similarity from an external vocabulary corpus to gauge the similarity between given documents. Additionally, Kenter et al. [30] introduces a model that transitions from word-level to text-level semantics, combining insights from methods reliant on external sources of semantic knowledge with word embeddings to estimate similarity.

In contrast to previous similarity studies that primarily focus on pure natural language analysis and often yield high-quality results, these methods can be exceptionally time-consuming, especially when dealing with lengthy documents. The challenge is even greater in patent similarity analysis, where the text is highly condensed and the main body of a patent is often inaccessible. Therefore, researchers relying solely on information from patent abstracts, titles, or other brief documents may find it insufficient for accurately estimating the similarity between patents. Additionally, given that the volume of patents is vast and rapidly growing (3.46 million patent applications were submitted in 2022 according to the World Intellectual Property Organization’s annual World Intellectual Property Indicators report), it is crucial to have a similarity estimation method that incorporates background knowledge and operates swiftly and effectively with limited-length text. To address this challenge, this article starts by preprocessing the raw patent document data, including the title and abstract, and then uses BERT to convert the tokenized and stop-word-removed text into a fixed-size matrix. Following this, an auto-encoder model is applied to the BERT matrix to reduce noise and address the positive constraints of NMF algorithms, which is then used to generate the IPC intermediary variables matrix. Finally, patent similarity was estimated using Cosine similarity on the intermediary variables matrix, and we assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of this method using a global dataset related to artificial intelligence patents. The paper concludes with a summary of our research, highlighting the limitations of our model and suggesting potential directions for future work.

3. Method

In this paper, we focus on the IPC category and abstract content of patents. The previous studies on NLP, particularly in semantic analysis, have shown that traditional NLP models often lack transparency and struggle with flexible grammar languages (e.g., Chinese, Japanese), making common NLP technologies like SVO difficult to apply and often resulting in poor performance. In response to these issues, our estimator is designed to enhance model explainability and reduce data requirements.

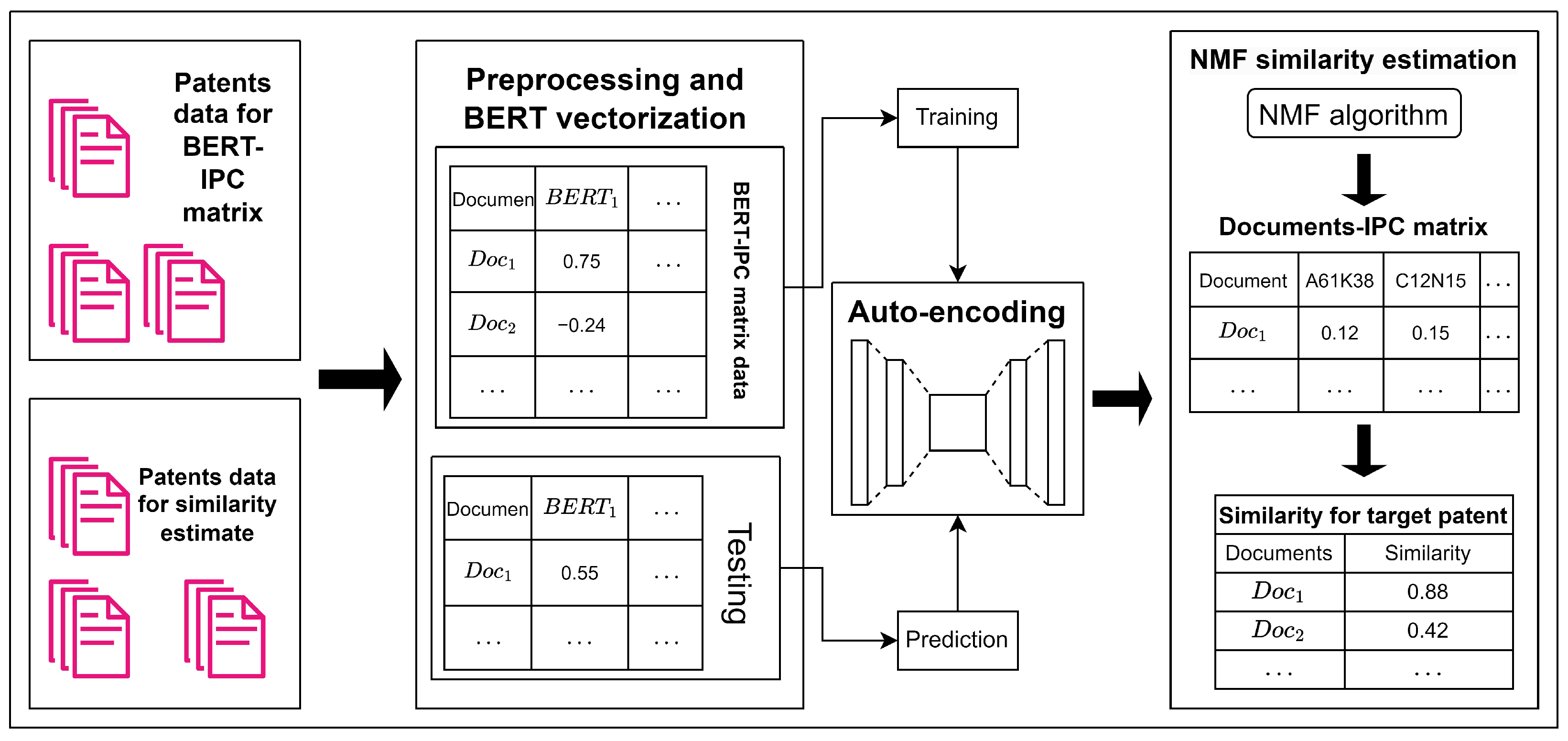

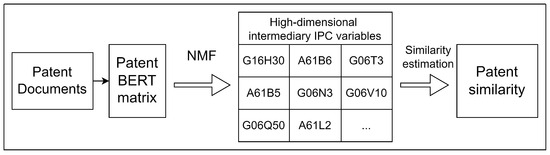

The estimator in this paper comprises three components: abstract vectorization using BERT, an auto-encoder model to reduce noise and enforce positive constraints, and an NMF-decomposed documents-IPC matrix. The workflow involves extracting semantic features from patent abstracts using BERT vectorization, refining these features with an auto-encoder for denoising and enforcing non-negativity, and then applying NMF to build a document-to-IPC matrix for estimating patent similarities, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Main process of patent similarity estimation.

3.1. Text Preprocessing and Vectorization

To integrate patent IPC and abstract information, the first step involves NLP preprocessing of the abstract. This phase includes converting all text to lowercase and removing unnecessary elements such as numbers, punctuation, special characters, and non-relevant languages. After preprocessing, tokenization is performed using the classic ‘word_tokenize’ tokenizer from NLTK, followed by the removal of stop words to enhance NLP analysis, with the stop word list used in this paper compiled from various sources, including input method websites and GitHub. Finally, BERT was used for context vectorization, with its architecture comprising three main components: the input layer (handling token, segment, and position embeddings), the transformer encoder layers (featuring multiple layers of multi-head attention, feed-forward networks, and residual connections), and the output layer, which generates contextualized embeddings for each token. To generate sparse representations in BERT, researchers introduce sparsity-promoting mechanisms during training, such as applying sparse regularizers like L1 regularization on model weights or using activation functions like rectified linear units (ReLU), exponential linear units (ELU), and their variants. Additionally, many research groups enhance BERT’s input by incorporating document expansion, which involves adding likely search terms to a document to improve its relevance to specific queries while maintaining the sparsity of the outputs. The BERT model used in this paper is ‘multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1’, which maps short natural language content (up to 512 tokens, such as sentences and paragraphs) into a 768-dimensional dense vector and is specifically designed for semantic search. This robust model was trained on 215 million question–answer pairs using a loss function called multiple negatives ranking loss. Ultimately, after preprocessing and BERT vectorization, all patent abstract contents were converted into uniformly sized vectors, creating the documents–BERT matrix. An auto-encoder model is then applied to satisfy the positive constraints of the NMF algorithm.

The auto-encoder model is a type of neural network used for unsupervised learning, comprising two main components: the encoder and the decoder. It learns efficient data representations by compressing the input into a lower-dimensional space via the encoder and then reconstructing the original data from this representation through the decoder. Since patent abstracts are highly specialized and differ significantly from everyday language, potentially making them “low-quality” data for the general BERT model and introducing noise, this paper mitigated this by incorporating an auto-encoder, a powerful noise reduction model. In the learning process of an auto-encoder, through iterative training, it learns to filter out random noise that does not contribute to the essential data structure, producing a denoised output that closely resembles the original data with the noise effectively removed. Another advantage of the auto-encoder is its high adaptability in scaling compared to simple scaling techniques (e.g., min–max scaler). The auto-encoder, with its multiple layers, can learn complex, hierarchical data representations and capture intricate patterns and relationships, while its use of non-linear activation functions provides flexibility in modeling these relationships and ensuring positive outputs. Additionally, simple scaling methods merely transform input features without learning from the data, limiting their ability to handle constraints effectively and model non-linear relationships or complex interactions between variables. Therefore, in this paper, an auto-encoder was used for noise reduction and scaling to enforce positive output constraints, ensuring compliance with the requirements of NMF.

The auto-encoder features a symmetric design in which both the encoder and decoder share identical structures, each comprising an input layer, hidden layers, and an output layer, with the encoder’s input layer and the decoder’s output layer matched to the dimensions of the input data. In the auto-encoder model, the input data denoted as v passes through an encoder with k hidden layers, producing output states , and a decoder with s hidden layers, producing output states , with activation functions for the encoder and for the decoder.

Training an auto-encoder simply means solving the optimization functions with the given function and and can be expressed as

where represents the difference between the input and output of the auto-encoder process, serving as the loss function, with the mean squared error being used in this research. The BERT output in this paper is sparse, with values mostly between −1 and 1. To meet the positive constraints of NMF, the activation functions and were chosen. Since the auto-encoder model requires a positive output, ideally between 0 and 1, the BERT output was normalized using a min-max scaler before applying the auto-encoder process. Additionally, to assess performance while accounting for the sparsity in BERT outputs, this paper applied and compared two loss functions: mean-squared error and binary cross-entropy. The equations are shown below.

Activate function:

Min-max scaler:

Mean-squared error loss function:

Binary cross entropy:

After the auto-encoder process, all documents are prepared for non-negative matrix factorization, named ‘documents-encoder’.

3.2. Construction of the Document–IPC Matrix

To construct the document–IPC matrix, we employed the NMF algorithm on the training patent data. The NMF algorithm starts with two datasets: a corpus of the IPC–encoder matrix represented by H, and the document–IPC matrix denoted as W. Then, the document–encoder matrix A can be obtained through the NMF algorithm by conducting the following factorization:

To clarify this process, we can also write this process in another format:

To numerically solve this problem, it is traditionally formulated as following optimization problems,

Euclidean-distance-based optimization problem:

divergence-based optimization problem:

where both optimization problems are subject to the constraints and . Although these problems are not convex in both W and H simultaneously, they are convex in W or H individually. Therefore, the fundamental approach to solving this problem is known as ‘alternating least squares’, which iteratively repeats the following two steps until convergence: fixing matrix W to find the optimal matrix H and then fixing matrix H to find the optimal matrix W. Building on this concept, multiple update rules were developed. Specifically, for the second norm distance optimization Problem (2), the update rule is shown below:

For divergence optimization Problem (3), the update rules are

The detailed proof was provided in the research by Daniel et al. [31]. Compared to distance-based optimization, divergence-based problems can be unstable due to the asymmetry between A and , leading to a greater focus on distance-based approaches in the research. In the context of this paper, traditional update rules may not be suitable because the one-hot encoding used to vectorize IPC—where values are either 0 or 1—can result in extremely slow convergence, particularly with large datasets. Furthermore, to maintain the sparsity of IPC, we adopt an alternative NMF algorithm developed by the research group led by Pedregosa et al. [32] to solve optimization Problem (2), which incorporates the update rules proposed by Cichocki et al. [33] and Fevotte et al. [34]. The basic update rules they used are

and

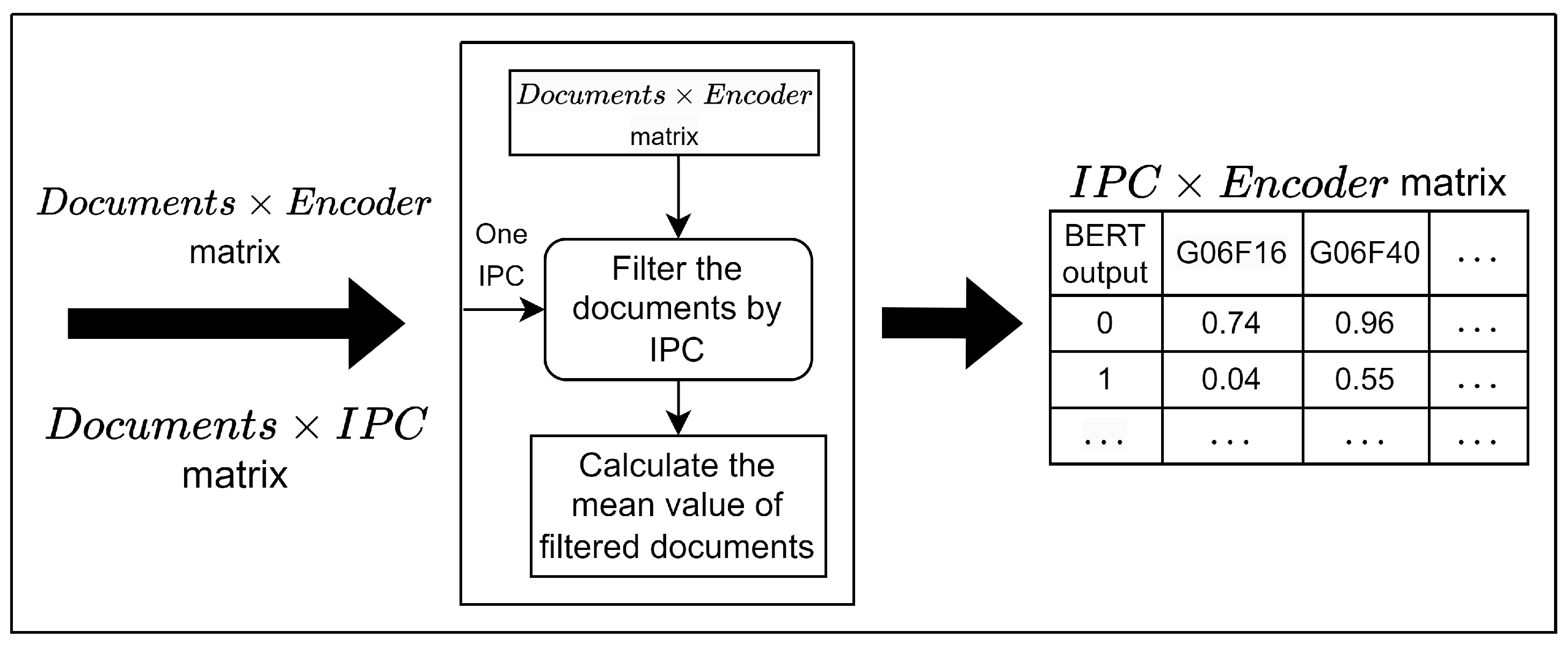

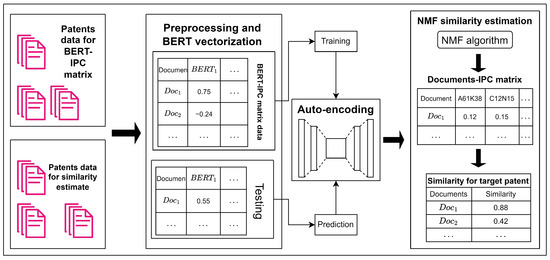

For the given matrix A, the update rules begin with randomly initialized, non-negative, and not all zero matrices W and H, with the updated results being normalized to simplify the calculation process. Once the matrices and are given, their output is unique for a fixed update strategy (though it may vary across different strategies), and according to the definition of convex sets and alternating least squares, the NMF outputs and can be considered as the paths ‘closest’ to the initial matrices and . By default, the initial matrices and are selected randomly, but this random initialization can lead to an inconsistent IPC-encoder matrix. Therefore, to stabilize the NMF results in this research, the initial matrices and were carefully selected, with representing the IPC matrix and being determined through the following steps, as outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Main process to construct IPC–encoder matrix.

- Initially, patents are grouped based on IPC codes, each category containing a sufficient number of patent documents denoted as .

- Next, for each IPC category , the documents in the document–encoder matrix are filtered and grouped, after which the mean value for each encoder score is calculated.

- Repeat this process for all IPC categories and use the resulting values to construct the IPC–encoder matrix, which serves as the initial matrix in the NMF algorithm.

After completing the initialization of the IPC–encoder matrix, it is applied to the NMF algorithm, denoted as v . Finally, by solving Equation (2) with and using NMF algorithms, the final and unique IPC–encoder output matrix is generated.

3.3. Patent Similarity Estimation

As previously mentioned, with the help of BERT, each patent is represented as a fixed-length vector, and the IPC–encoder matrix H has already been calculated from the previous process. At this stage, to estimate the similarity between a given patent denoted as , the document–IPC matrix must first be computed, which can be summarized as the following problem:

For solving Problem (4), there are three main methods:

- Transform the padded predicted document–IPC matrix using the same NMF algorithm applied during the construction of the IPC–encoder matrix, allowing for a single-step update under the already established update rule for the calculated IPC-encoder matrix H.

- For each padded predicted document , repeatedly solve the optimization problem: , until predictions are completed for all documents.

- Directly solve the equation , where the result is .

For the third method, the matrix must be non-singular, which may not always be the case, and calculating the inverse can be time-consuming. For the second method, various algorithms can be used to solve the optimization problem, such as ‘L-BFGS-B’, conjugate gradient, and the Nelder–Mead algorithm. While this method generally works well, it can occasionally lead to significant overfitting problems, and the one-by-one calculation for padding patents can be time-consuming. Therefore, in this paper, the first method is applied. After solving Problem (4), the document–IPC matrix for all padding predicted patents is computed, denoted as , which successfully integrates abstract and IPC category information and will be used later to estimate similarity.

In the final step, after calculating the document–IPC matrix by solving Problem (4) for the padding patent documents, we proceed to estimate similarity. This paper focuses on the cosine similarity measures:

where and are the document IPC vectors needed to estimate similarity. In this research, each element represents the updated IPC score, integrating the abstract and original IPC category for the given document. The similarity scores range from −1 to 1, with negative values indicating a negative relationship and 0 indicating no similarity. Compared to traditional estimators that rely solely on the one-hot encoding of IPC categories or pure NLP methods applied to abstracts, the method used in this research, which integrates NMF into patent similarity estimation, enhances the model’s explanatory power and transparency, facilitating the identification of patents with similar technical features.

4. Case Study: Artificial-Intelligence-Related Patents

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has become critically important worldwide, especially for economic growth. However, with substantial investments in AI driving the rapid pace of technological change, it has become increasingly urgent for researchers to identify “right” development directions (those likely to be profitable) and avoid “wrong” directions that could lead to losses, where patent similarity plays a fundamental role. To demonstrate the method outlined in this paper, we applied it to a dataset of approximately 10,000 AI-related patents from 2003 to 2023, covering 2121 main IPC categories, though around 1950 of these categories contain fewer than 30 patents.

Next, to evaluate the performance of our estimator, we conducted subject–action–object (SAO) analysis, a commonly used technique in natural language processing, on the patent data. However, the highly condensed nature of patent content, coupled with strict limitations on abstract length (resulting in fewer common words and simplified SAO phrase structures) may reduce the effectiveness of this approach. In this study, the SAO similarity score comprises three elements, subject, verb, and object, with the following formula provided:

where , , and represent the lists of subjects, verbs, and objects, respectively, found within the token list p. Furthermore, BERT, which is regarded as a state-of-the-art NLP method, has already been demonstrated to exhibit significant efficiency in natural language content analysis by multiple researchers. Hence, instead of employing other deep learning methods, this paper evaluates the performance of our estimator by comparing it with manual reading, traditional NLP techniques like TF-IDF, standalone BERT, NMF with MSE, NMF with BCE, SAO, and BERT directly combined with IPC. The detailed analysis and results will be presented in the Section 5, with the IDs of ten out of the fifty test patents listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ten of fifty test patents in this paper (see “Appendix A” for all AI test patents ID).

As previously noted, the majority of patents are concentrated in a small number of IPC categories, with over 90% of categories being underrepresented. Initially, we attempted resampling techniques to address the categories with fewer patents, but this significantly increased training times and noise. Therefore, this paper focused on IPC categories with at least 300 distinct patents, excluding categories with fewer patents, which reduced the dataset to 7187 documents and narrowed the relevant IPC categories to 20: G06F16, G06F21, G06Q10, G06N5, G06Q30, A61B5, G06Q50, G06V40, H04L67, G06F9, G06V10, G06F40, G06F18, G06F3, G06T7, G10L15, G06V20, G06N3, G06N20, and G16H50. Afterward, 50 patients were randomly selected for similarity testing, while the remaining patents were used to construct the document-encoder matrix and train the NMF model.

Next, after preprocessing the abstracts by removing special characters, stop words, and other language symbols (e.g., Chinese, Japanese), the tokens were concatenated into a single long sentence and processed using BERT. Upon completion of this process, all patent files were represented as vectors of uniform length (768), utilizing the BERT model (multi-qa-mpnet-base-dot-v1), which was developed using diverse data sources, including WikiAnswers, Stack Exchange, Natural Questions, and Quora Question Triplets.

IPC–Encoder Matrix Development

As outlined in the Section 3, an auto-encoder model was used to denoise the BERT scores and enforce positive output constraints, employing sigmoid and tanh activation functions, with the data split into 70% for training and 30% for testing, applying min-max scaling for enhancement, and subsequently constructing the IPC–encoder matrix via NMF. Due to the introduction of random values during the auto-encoder process, multiple iterations were conducted, with the auto-encoder and similarity estimation being run approximately 100 times in this study. The entire encoding/decoding process in our model can be summarized in Table 2. After encoding and decoding all BERT data, the NMF algorithm was applied to estimate the similarity scores and the order from the highest to lowest.

Table 2.

The hidden layers setting in auto-encoder.

5. Results

In this paper, as previously mentioned, patent similarity in AI-related data was assessed using seven methods (manual sorting, traditional similarity estimation via TF-IDF, SVO, BERT-based calculations, scaled BERT with IPC categories, NMF-based with MSE, and NMF-based with BCE), with the NMF results averaged over 100 iterations for consistency. Detailed information on the target patent is provided in Table 3, and the detailed similar scores are provided in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 3.

Target patent used to compare the similarity for AI example.

Table 4.

The top 5 patents on similarity estimation for AI-related data.

Table 5.

The bottom 5 patents on similarity estimation for AI-related data.

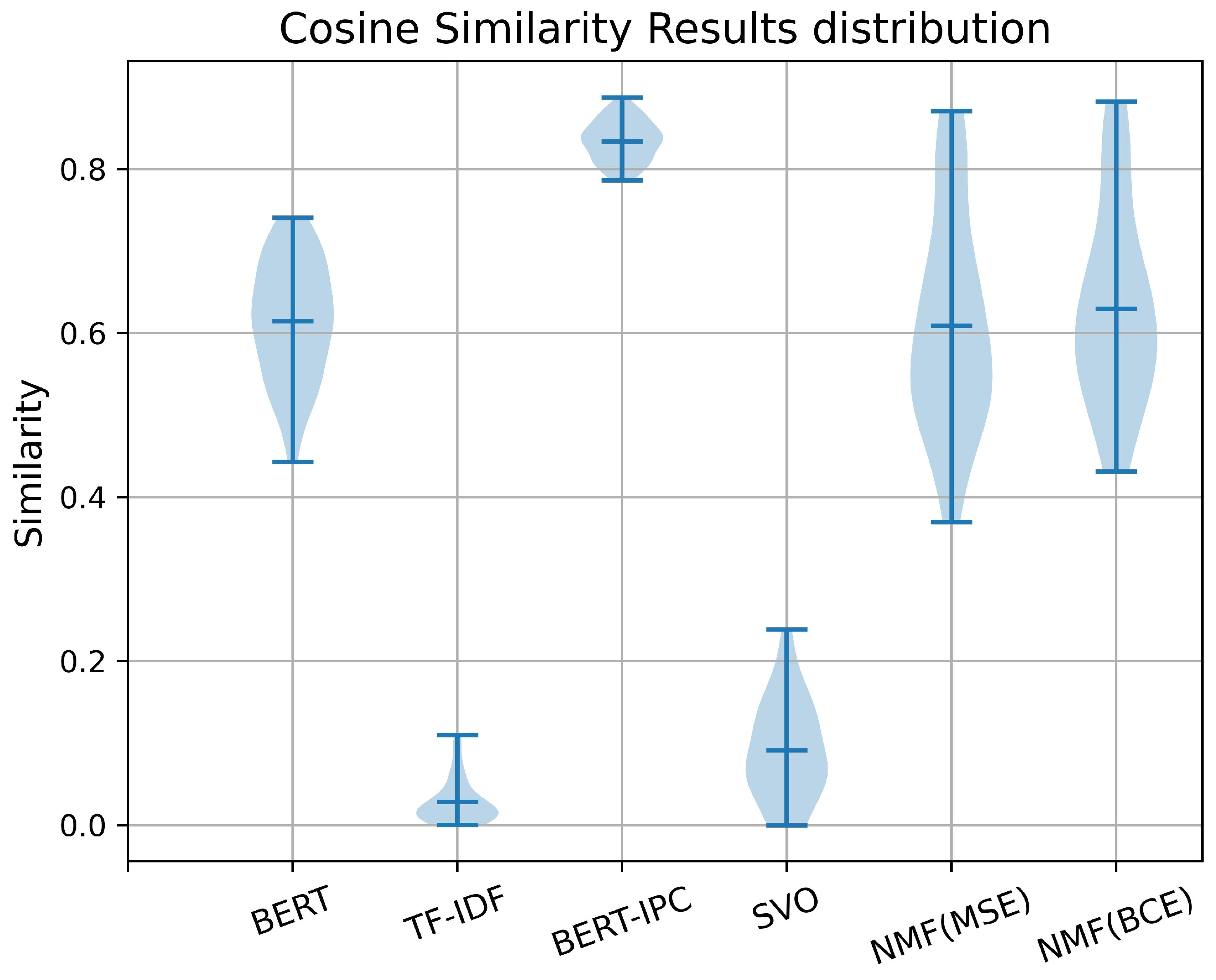

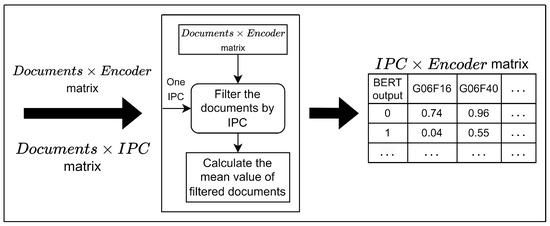

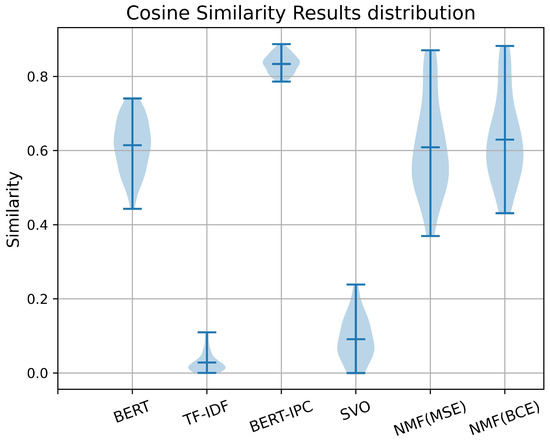

In Figure 4 and Table 6, the results indicate that TF-IDF, similar to BERT-IPC, produced the narrowest range of similarity scores, making it ineffective for distinguishing patent similarities. Given that all patents are AI-related and higher similarity scores are expected, both the TF-IDF and SVO methods were found to be unsuitable for this task. In contrast, pure BERT and NMF-based methods yielded more reasonable similarity scores and demonstrated a better overall distribution, making them more effective for this task. Additionally, the NMF models with varying auto-encoder loss functions (MSE and BCE) yield similar results, though BCE provides a slightly more compact representation.

Figure 4.

Distribution of similarity scores for all methods.

Table 6.

The summary of patents distribution.

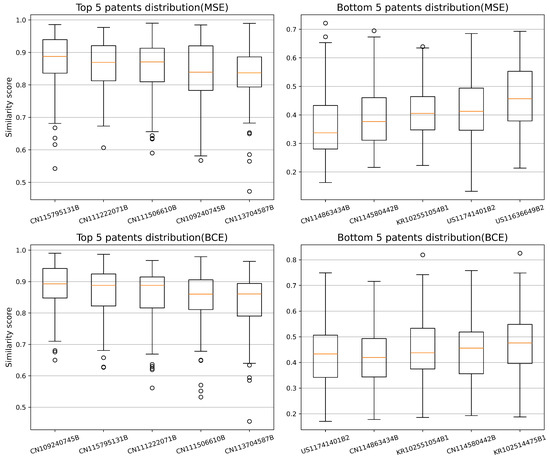

Figure 5, along with Table 7 and Table 8, presents the distribution of the top 5 and bottom 5 patent similarity scores for both MSE and BCE loss functions, averaged over 100 runs of the auto-encoder. The results indicate that while the similarity scores estimated by both methods are generally comparable, NMF-BCE produces slightly higher scores than NMF-MSE, and for both methods, the distribution becomes more diverse for less similar patents. Aside from the similarity distribution, Table 4 and Table 5 present the similarity scores for the top 5 and bottom 5 patents most similar to the target patent from a set of 50 test patents, while Table 9 compares the manual rankings with the similarity estimates from the different methods, and Table 10 and Table 11 present detailed information on the most and least similar patents, as estimated manually.

Figure 5.

Distribution of similarity scores across 100 runs for the top and bottom 5 patents.

Table 7.

The top 5 and bottom 5 patents for NMF using MSE across 100 runs of the auto-encoder.

Table 8.

The top 5 and bottom 5 patents for NMF using BCE across 100 runs of the auto-encoder.

Table 9.

Top 5 and bottom 5 patents on AI similarity estimation.

Table 10.

The most similar patent estimate manually.

Table 11.

The least similar patent estimate manually.

In this example, the target patent describes a method for analyzing product trend prediction through content and social data analysis, involving data collection, key information extraction, and analysis. Hence, similar patents are expected to focus on information analysis, knowledge extraction, platform services, data processing and analysis, and other related fields. However, patent KR102551054B1, which describes a key technology for X-ray imaging devices, is entirely unrelated to the target patent, and both NMF-based methods, SVO, and TF-IDF correctly rank it among the five least similar patents. In contrast, patent CN111222071B, which addresses information interaction and questionnaire processing using data processing and knowledge extraction methods similar to the target patent, is accurately identified by NMF-based methods as one of the five most similar patents. Additionally, from our experiment, it’s evident that the TF-IDF scores are exceedingly low, with the majority falling below 5%. This is attributed to the fact that although these patents pertain to AI topics such as data processing and knowledge discovery, they often lack common words. Additionally, the limited text length and substantial compression of information contribute to the low scores.

6. Conclusions

With the development of science and economic globalization, intellectual property has become a crucial component in both company and country competitiveness, with patents playing a key role. The recent research has explored comparing similarities using various NLP methods. However, due to the highly compressed text and the absence of background information, these NLP methods often yield low similarity scores within a narrow range, making further analysis challenging. Traditionally, IPC categories serve as a valuable source of background knowledge for a given patent. Unfortunately, only a few research groups have successfully attempted to integrate this information with the natural language content of the patent, such as the abstract, title, or other textual content. For those who have succeeded, most attempted direct integration of weighted IPC categories into the NLP-related results table and applied machine learning algorithms such as logistic regression, support vector machines, convolutional neural networks, long short-term memory, etc., to compare similarities. Unfortunately, in their process, the selection of weighted scores often lacks a rigorous argument, with researchers trying different weights and assessing the output performance based on test data acceptability.

The estimator introduced in this paper integrates both natural language text and background knowledge, and its score can be elucidated as a combination of different IPC category weights and the content of the given patent abstract. In practical applications, once the IPC–encoder matrix is constructed, there is no need to rebuild it for future use, thereby reducing costs and saving time. Our estimator is inspired by the concept of non-negative matrix factorization, a method commonly used in image analysis where each column of a grayscale image is treated as an independent vector. Through decomposition, a smaller-sized matrix allows for further analysis with reduced time and space consumption. Similar to image analysis, natural language text can be transformed into fixed-length vectors using BERT, resulting in a fixed-dimensional matrix that shares similar mathematical features, enabling analysis with comparable tools. In contrast to the narrow score range produced by methods like TF-IDF or BERT combined with IPC, our estimator facilitates a more comprehensive analysis for researchers. Furthermore, our estimator solely relies on a suitable document information matrix (in this study, generated using BERT), rendering it applicable in any language capable of transforming its text into a fixed-length vector.

Like other studies, our similarity estimator has certain limitations. Its primary drawback is the heavy reliance on the quality of BERT’s output, though the auto-encoder helps reduce noise and partially mitigates this dependence. A low-quality BERT model can lead to serious bias and introduce significant linearity issues, resulting in challenges with numerical computations, such as instability and poor convergence. For future research, two potential directions could be pursued: first, enhancing the construction of BERT-related matrices, similar to the integrated method incorporating IPC categories used in this paper; second, applying control theory to design matrix factorization methods. Currently, only non-negative matrices exhibit convexity in NMF, so developing a generalized factorization algorithm is another promising avenue. However, since categorical data like IPC are not always available for most scientific content, a further discussion on feature selection is necessary. Therefore, we plan to explore natural language text factor selection in greater depth, enabling this estimator to be applied to a wider range of text types.

Author Contributions

Z.J.; conceptualized and designed the study, formulated all algorithms, and wrote the manuscript. W.T. and W.L. conducted the data analysis. K.S. and F.W. interpreted the results. C.R. provided data and software. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code used in this study are available on GitHub at https://github.com/zhixuan1994/Patent-similarity-by-NMF.git (accessed on 20 October 2024) for purposes of replication and further research. Additionally, they will be deposited in a publicly accessible repository upon publication to ensure transparency and facilitate broader access to the research community.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests relevant to this research.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Patent ID for testing.

Table A1.

Patent ID for testing.

| Patent ID | Patent ID | Patent ID | Patent ID | Patent ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KR102502575B1 | CN111222071B | KR102514475B1 | CN115795131B | ES1296514Y |

| CN112992141B | CN113688907B | CN114579707B | US11741606B2 | CN110880082B |

| CN113298391B | CN110347807B | KR102499800B1 | KR102515539B1 | CN116167781B |

| US11588796B2 | CN111310701B | CN113704587B | US11663167B2 | US11698965B2 |

| JP7335293B2 | CN111506610B | CN116313164B | US11718311B2 | CN110675312B |

| CN114170803B | CN116152668B | CN113707253B | CN114863434B | CN115331048B |

| CN113269806B | KR102551054B1 | CN112507081B | US11695805B2 | US11636649B2 |

| US11741401B2 | CN112365074B | CN114580442B | CN113377909B | CN109240745B |

| CN115482837B | US11580339B2 | CN110990545B | CN112116156B | CN114760121B |

| TWM642386U | CN113297480B | JP7267342B2 | US11734546B2 | CN110609898B |

References

- Abbas, A.; Zhang, L.; Khan, S.U. A literature review on the state-of-the-art in patent analysis. World Pat. Inf. 2014, 37, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, F.; Nürnberger, A. Overview of prior-art cross-lingual information retrieval approaches. World Pat. Inf. 2012, 34, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, O.; Huang, H.; Ren, J.; Xie, L.; Xiao, Y. Contrastive learning with text augmentation for text classification. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 19522–19531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L.; Chiu, Y.T. An IPC-based vector space model for patent retrieval. Inf. Process. Manag. 2011, 47, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, G.; Shin, J.; Lee, S. Impact of preprocessing and word embedding on extreme multi-label patent classification tasks. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 4047–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Salathé, M.; Kummervold, P.E. COVID-Twitter-BERT: A natural language processing model to analyse COVID-19 content on Twitter. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1023281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.M.; Jang, M.J.; Yum, Y.J.; Kim, S.; Shin, U.; Kim, Y.M.; Joo, H.J.; Song, S. A pre-trained BERT for Korean medical natural language processing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.R.; Pethe, C.; Skiena, S. Natural language processing versus rule-based text analysis: Comparing BERT score and readability indices to predict crowdfunding outcomes. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2021, 16, e00276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licari, D.; Comandè, G. ITALIAN-LEGAL-BERT models for improving natural language processing tasks in the Italian legal domain. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2024, 52, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bakshi, B.R.; Ramteke, M.; Kodamana, H. Recycle-BERT: Extracting Knowledge about Plastic Waste Recycling by Natural Language Processing. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 12123–12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, Z.; Byun, Y. Topic modeling in short-text using non-negative matrix factorization based on deep reinforcement learning. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 39, 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Iltaf, N.; Afzal, H.; Abbas, H. Enriching Non-negative Matrix Factorization with Contextual Embeddings for Recommender Systems. Neurocomputing 2020, 380, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, S.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Y. Learning Topics in Short Texts by Non-negative Matrix Factorization on Term Correlation Matrix. In Proceedings of the 2013 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM), Austin, TX, USA, 2–4 May 2013; pp. 749–757. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, L.; Dai, T.; Guo, L.; Cao, S. Non-negative matrix factorization for implicit aspect identification. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 11, 2683–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, P.; Roy, N.R. Comparison between LDA & NMF for event-detection from large text stream data. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Computational Intelligence & Communication Technology (CICT), Ghaziabad, India, 9–10 February 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbat, N.; Anoun, H.; Hassouni, L. Topic Modeling and Sentiment Analysis with LDA and NMF on Moroccan Tweets. In Proceedings of the Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 4, Karabuk, Turkey, 7–9 October 2020; Ben Ahmed, M., Rakıp Karaș, İ., Santos, D., Sergeyeva, O., Boudhir, A.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoya; Latif, S.; Shafait, F.; Latif, R. Analyzing LDA and NMF Topic Models for Urdu Tweets via Automatic Labeling. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 127531–127547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xin, Y.; Hochberg, E.; Joshi, R.; Uzuner, O.; Szolovits, P. Subgraph augmented non-negative tensor factorization (SANTF) for modeling clinical narrative text. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pudasaini, S.; Shakya, S.; Lamichhane, S.; Adhikari, S.; Tamang, A.; Adhikari, S. Application of NLP for Information Extraction from Unstructured Documents. In Proceedings of the Expert Clouds and Applications, Bangalore, India, 18–19 February 2021; Jeena Jacob, I., Gonzalez-Longatt, F.M., Kolandapalayam Shanmugam, S., Izonin, I., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; El-Gohary, N.M. Semantic NLP-Based Information Extraction from Construction Regulatory Documents for Automated Compliance Checking. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2016, 30, 04015014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivetti, E.A.; Cole, J.M.; Kim, E.; Kononova, O.; Ceder, G.; Han, T.Y.J.; Hiszpanski, A.M. Data-driven materials research enabled by natural language processing and information extraction. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2020, 7, 041317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, S.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, J.H.; Seok, J.; Joo, H.J. Validation of deep learning natural language processing algorithm for keyword extraction from pathology reports in electronic health records. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yu, H.; Cai, X.; Geng, Y.; Li, G.; Xu, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y. Multi-attention deep neural network fusing character and word embedding for clinical and biomedical concept extraction. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J. Hybrid Feature Fusion Learning Towards Chinese Chemical Literature Word Segmentation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 7233–7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S. Improved Technology Similarity Measurement in the Medical Field based on Subject-Action-Object Semantic Structure: A Case Study of Alzheimer’s Disease. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Heng, X.; Zhu, D. Identifying R&D partners through Subject-Action-Object semantic analysis in a problem & solution pattern. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 29, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhu, D. Subject–action–object-based morphology analysis for determining the direction of technological change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 105, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Inkpen, D. Semantic Text Similarity Using Corpus-Based Word Similarity and String Similarity. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2008, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, T.; de Rijke, M. Short Text Similarity with Word Embeddings. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Melbourne, Australia, 18–23 October 2015; CIKM’15. pp. 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.D.; Seung, H.S. Algorithms for non-negative matrix factorization. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 1 January 2000; NIPS’00. pp. 535–541. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- CICHOCKI, A.; PHAN, A.H. Fast Local Algorithms for Large Scale Nonnegative Matrix and Tensor Factorizations. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. 2009, E92.A, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Févotte, C.; Idier, J. Algorithms for Nonnegative Matrix Factorization with the beta-Divergence. Neural Comput. 2011, 23, 2421–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).