MHD Taylor–Couette Flow of Oldroyd-B Fluids Through a Porous Medium in an Annulus Induced by Time-Dependent Couples

Abstract

:1. Introduction

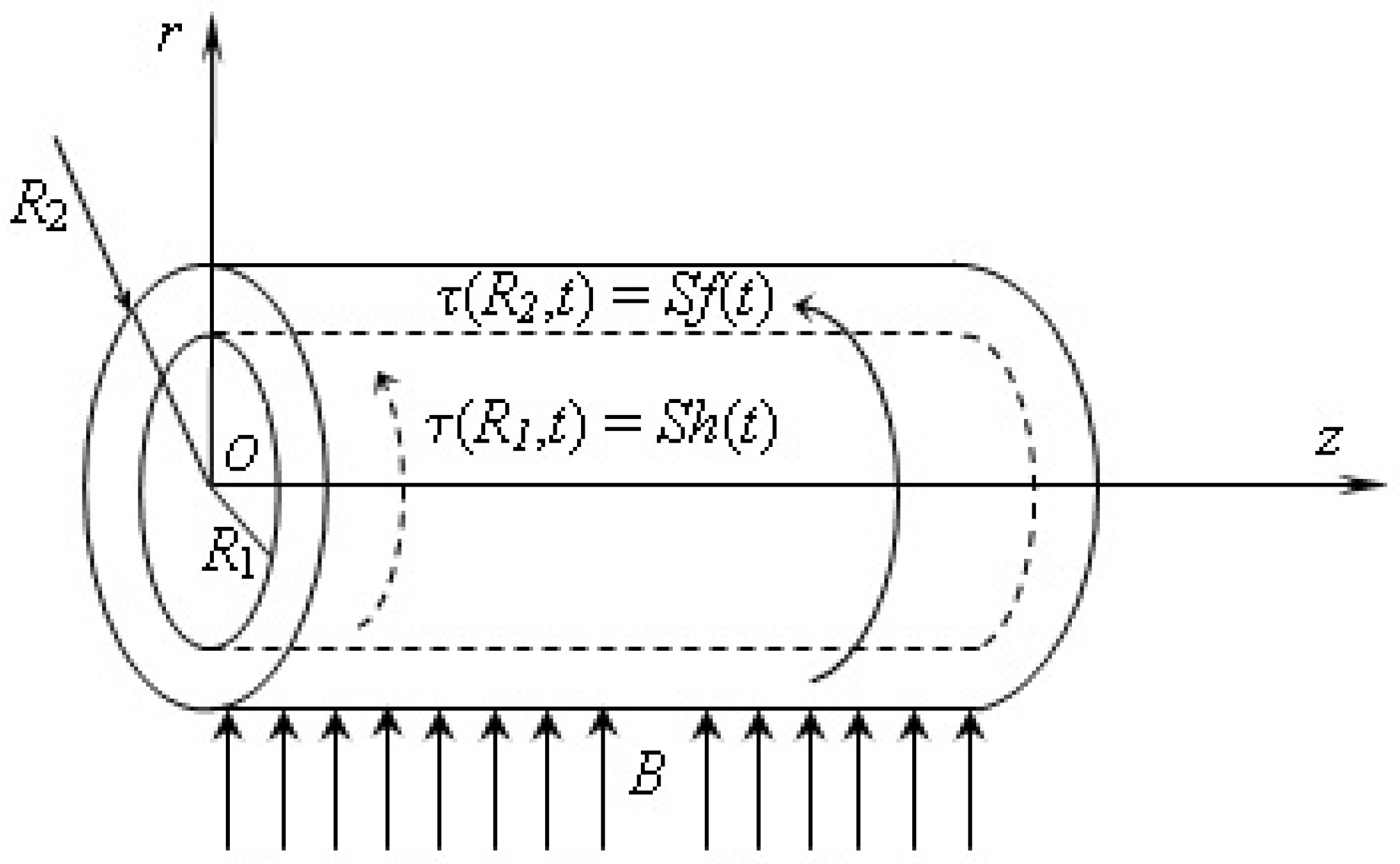

2. Problem Presentation

3. Solution

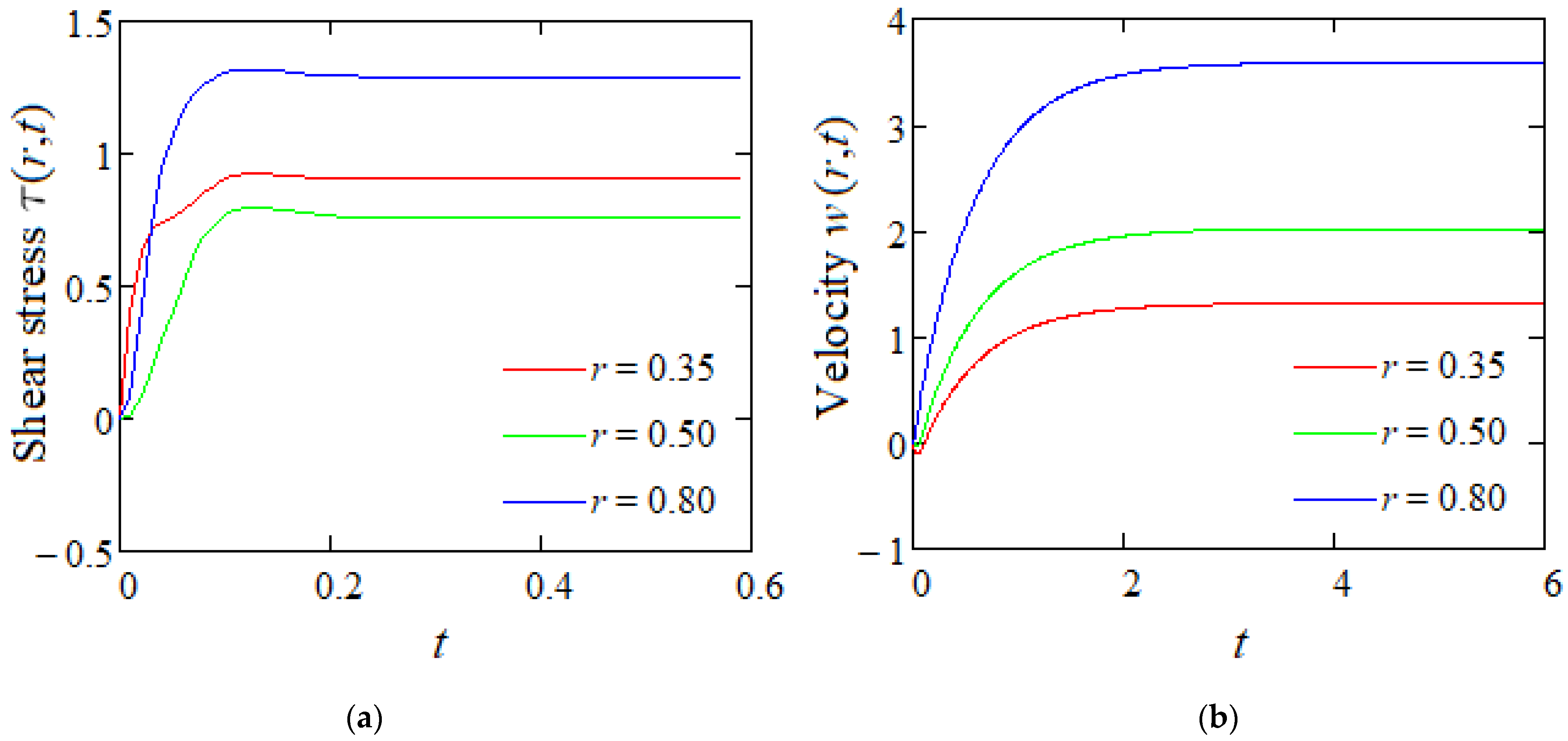

3.1. Calculation of the Dimensionless Shear Stress

3.2. Calculation of the Dimensionless Velocity and Darcy’s Resistance

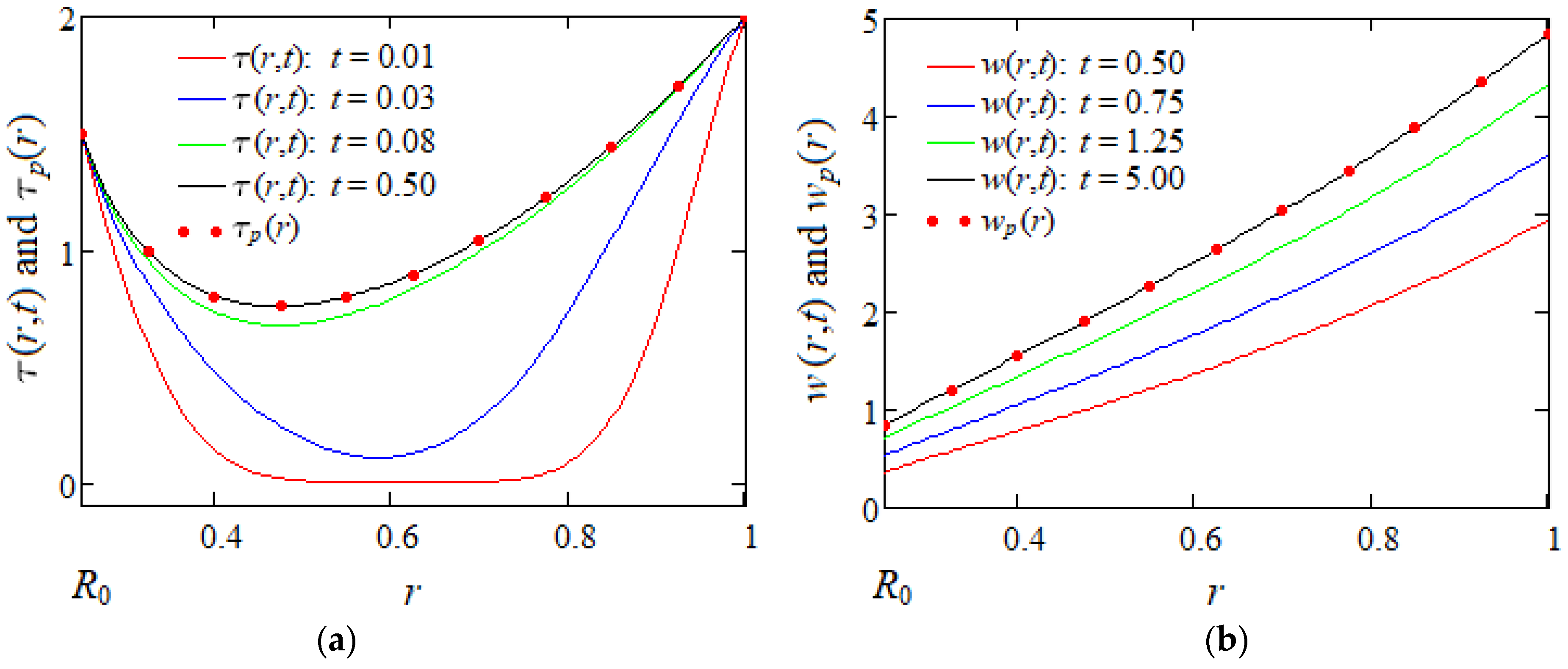

4. Limiting Case R0 → 0

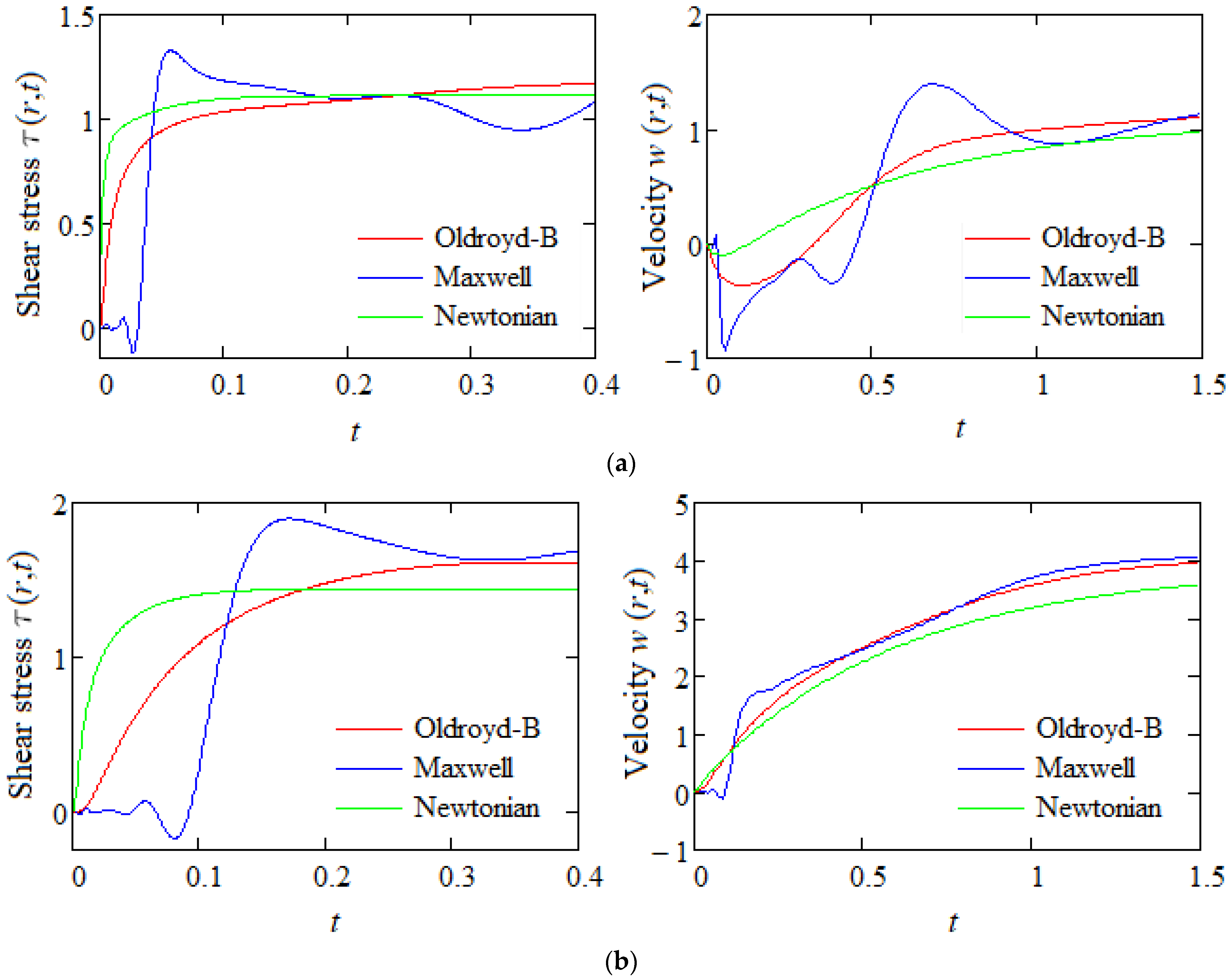

5. Some Numerical Results

6. Conclusions

- -

- The main outcomes that have been obtained by this study are:

- -

- The Taylor–Couette flow of ECIOBFs through a porous medium induced by time-dependent couples in an annulus was investigated in the presence of a magnetic field.

- -

- Closed-form expressions are established for the dimensionless shear stress and fluid velocity. A particular case is considered and the steady solutions are also provided.

- -

- The solutions for a Taylor–Couette flow of same fluids induced by time-dependent couple in an infinite circular cylinder were obtained as limiting cases of previous results.

- -

- The convergence of starting solutions to their steady components was graphically proven and the necessary times to touch the permanent state were found.

- -

- The permanent solutions, which are the same for flows of incompressible Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids, do not depend on parameters M and K independently and a two-parameter approach is superfluous.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Cauchy stress tensor | |

| Identity tensor | |

| Extra-stress tensor | |

| Rate of deformation tensor | |

| and | Radii of the coaxial circular cylinders |

| Hydrostatic pressure | |

| [m/s] | Velocity vector |

| Electrical conductivity | |

| Electrical conductivity Vieru | |

| Cylindrical coordinates | |

| Darcy’s resistance | |

| Strength of the applied magnetic field | |

| Permeability of porous medium | |

| w[m/s] | Fluid velocity |

| M | Dimensionless magnetic parameter |

| K | Dimensionless porosity parameter |

| Standard Bessel functions | |

| Hankel transform of function of the function | |

| Dynamic viscosity | |

| Relaxation time | |

| Retardation time | |

| Fluid density | |

| Kinematic viscosity | |

| Shear stress | |

| Dirac distribution |

Appendix A

References

- Waters, N.D.; King, M.J. The unsteady flow of an elastico-viscous liquid in a straight pipe of circular cross section. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1971, 4, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, K.R.; Bhatnagar, R.K. Exact solutions for simple flows of an Oldroyd-B fluid. Acta Mech. 1995, 113, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.P. Transient viscoelastic helical flow in pipes of circular and annular cross-section. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2001, 100, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetecau, C. Analytical solutions for non-Newtonian fluid flows in pipe-like domains. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2004, 39, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, S.; McKee, S.; McDermott, R. Analytic solutions of Newtonian and non-Newtonian pipe flows subject to a general time-dependent pressure gradient. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2009, 162, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetecau, C.; Imran, M.; Fetecau, C. Taylor-Couette flow of an Oldroyd-B fluid in an annulus due to a time-dependent couple. Z. Naturforschung A 2011, 66, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Khan, N.A. Axial Couette flow of an Oldroyd-B fluid in an annulus. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 2012, 2, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Tahir, M.; Imran, M.A.; Awan, A.U. Taylor-Couette flow of an Oldroyd-B fluid in an annulus subject to a time dependent rotation. Am. J. Appl. Math. 2015, 3, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Tanveer, M.; Bajwa, S. Study of velocity and shear stress for unsteady flow of incompressible Oldroyd-B fluid between two concentric rotating circular cylinders. Hacet. J. Math. Stat. 2019, 48, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Malik, R.; Anjun, A. Analytic solutions for MHD flows of an Oldroyd-B fluid between two side walls perpendicular to the plate. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2011, 198, 1415–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Rana, M.A.; Haroon, T.; Siddiqui, A.M. Applications of Sumudu transform to MHD flows of an Oldroyd-B fluid. Appl. Math. Sci. 2013, 7, 7027–7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Datta, S.K.; Sen, P. On hydromagnetic flow of an Oldroyd-B fluid between two oscillating plates. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2016, 2, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.C.; Masuoka, T. Stokes’ first problem for an Oldroyd-B fluid in a porous medium. Phys. Fluids 2005, 17, 023101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Imran, M.; Fakhar, K. New exact solutions for an Oldroyd-B fluid in a porous medium. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 2011, 2011, 408132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, T.; Shehzad, S.A.; Mustafa, M.; Hendi, A. MHD flow of an Oldroyd-B fluid through a porous channel. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2012, 10, Article ID A8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, Q.; Nazar, M.; Ali, U.; Imran, M. Unsteady flow of Oldroyd-B fluid through porous rectangular duct. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2013, 15, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.; Ijaz, A. Starting solutions for an MHD Oldroyd-B fluid through porous space. J. Porous Media 2014, 17, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, T.; Hussain, M.; Khan, M. Hall effect on flows of an Oldroyd-B fluid through porous medium for cylindrical geometries. Comput. Math. Appl. 2006, 52, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, S.E.E. MHD flow of an Oldroyd-B fluid through porous medium in a circular channel under the effect of time dependent pressure gradient. Am. J. Fluid Dyn. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, M.B.; Awrejcewicz, J.; Rehman, A.U. Functional effects of permeability on Oldroyd-B fluid under magnetization: A comparison of slipping and non-slipping solutions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetecau, C.; Vieru, D. Investigating Magnetohydrodynamic Motions of Oldroyd-B Fluids through a Circular Cylinder Filled with Porous Medium. Processes 2024, 12, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetecau, C.; Vieru, D.; Eva, L.; Forna, N.C. Memory effects in the magnetohydrodynamic axial symmetric flows of Oldroyd-B fluids in a porous annular channel. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelli, R.; Rajagopal, K.R. Start-up flows of second grade fluids in domains with one finite dimension. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 1995, 30, 817–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldroyd, J.G. On the formulation of rheological equations of state. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1950, 200, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossow, V.J. On flow of electrically conducting fluids over a flat plate in the presence of a transverse magnetic field. NACA TN Tech. Rep. 1957, 3971, 489–508. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, L.; Bhatta, D. Integral Transforms and Their Applications, 2nd ed.; Cgapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon, I.N. Fourier Transforms; McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA; Toronto, ON, Canada; London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fetecau, C.; Vieru, D. MHD Taylor–Couette Flow of Oldroyd-B Fluids Through a Porous Medium in an Annulus Induced by Time-Dependent Couples. Mathematics 2025, 13, 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13050719

Fetecau C, Vieru D. MHD Taylor–Couette Flow of Oldroyd-B Fluids Through a Porous Medium in an Annulus Induced by Time-Dependent Couples. Mathematics. 2025; 13(5):719. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13050719

Chicago/Turabian StyleFetecau, Constantin, and Dumitru Vieru. 2025. "MHD Taylor–Couette Flow of Oldroyd-B Fluids Through a Porous Medium in an Annulus Induced by Time-Dependent Couples" Mathematics 13, no. 5: 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13050719

APA StyleFetecau, C., & Vieru, D. (2025). MHD Taylor–Couette Flow of Oldroyd-B Fluids Through a Porous Medium in an Annulus Induced by Time-Dependent Couples. Mathematics, 13(5), 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13050719