Abstract

COVID-19 has led people to question numerous aspects of life, including family budgetary arrangements and wealth management. The COVID-19 pandemic has thrown many of us a financial curveball. Managing personal finances is important, particularly during a crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the economic consequences are evident, financially induced stress caused by uncertainty is less visible. Individual wealth increments and firm size measures have brought a commensurate increment in their respective resources. Thus, monitoring these resources and coordinate investment exercises is necessary to preserve resource development. The best method to improve wealth management banks is to consider competitive preferences by designating a set of wealth management bank selections to oversee individuals’ wealth viably. This paper provides a step-by-step assessment guide for wealth management banks using multiple-criteria decision-making to illustrate the appropriateness of the proposed technique. We found that the two primary aspects of wealth management bank evaluations are transaction safety and professional financial knowledge. The proposed approach is relatively straightforward and appropriate for such key decision-making issues.

1. Introduction

Wealth management is venture counseling combining monetary management, venture portfolio management, and several types of amassed budgetary management. The term private wealth management is often used to depict profoundly customized and advanced speculative management and money-related management conveyed to high-net-worth financial specialists [1]. As the world proceeds to learn from COVID-19, the prevalence of this virus may affect a few aspects of people’s lives. However, people can use this time as an opportunity to review their current budgetary circumstances and establish structures that ensure financial balance when the pandemic ends and the economy recovers or to prepare for a financial downturn., Improved financial planning can also be established based on a few months before the pandemic.

This financial planning incorporates exhorting the utilization of trusts and other dominant arranging vehicles, commerce progression, or stock option management and supporting subsidiaries for stock [2]. Wealth management allows speculators to determine the factors that are critical to financial specialists. As a result, significant procedures are developed to assist financial specialists in realizing and protecting their valuable trusts. Wealth management incorporates arranging ventures, protections, retirement, and resource assurance and assessments [1]. Wealth management banks help speculators to contribute cash to different venture markets according to the investors’ venture objectives, helping financial specialists to select from different guarantees, self-protection alternatives, and captive insurance companies. Retirement arrangements are fundamental to determining speculators’ reserve requirements for retirement. Wealth management banks start with the investor’s monetary advisor to determine the investor’s preferred way of life and then make a deal considering various factors, such as charges, instability, swelling, leases, and claims, to preserve this way of life. With the advancement of individual budgetary management in household banks, individual fund trade has become a key area of commercial household management regarding accounting and administration development [1,2].

This study proposes a novel hybrid method to address various interdependence and feedback problems in wealth management bank selection. This proposed model expands the understanding of the interrelationship between the assessment and determination measurements and sheds light on a complex and interactive wealth bank management issue that can improve decision quality.

We propose a strategy that helps government agencies and mechanical examiners achieve relative execution. Twenty specialists assessed wealth management banks using the proposed fuzzy Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) procedures with multiple-criteria decision-making (MCDM) [3,4]. The fuzzy TOPSIS was used to determine the inclination weights for the assessment and progress through the options between real and tested execution levels of each measurement [5,6].

The remainder of this paper is structure as follows. Section 2 summarizes the selection criteria for a wealth management bank. Section 3 presents expert interviews for the assessment system. Section 4 discusses the strategy, namely, the fuzzy TOPSIS, and Section 5 describes the investigation, providing the investigative process and strategy, and test determination and outcomes. Lastly, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

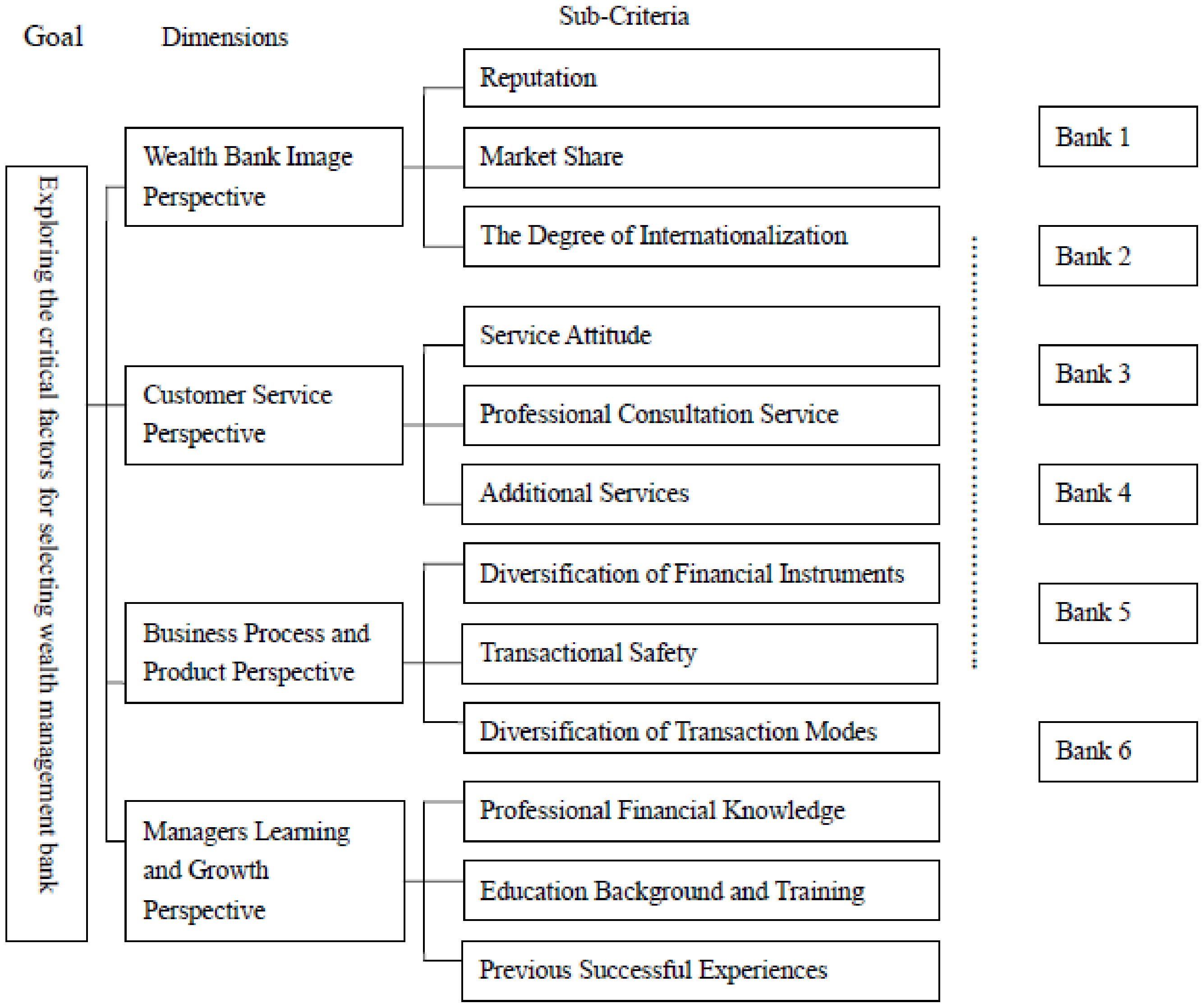

This section identifies the variable constraints for selecting a wealth management bank through a coordinated plan and assessment strategy. The leveled decision-making structure comprises four qualities that are discussed in detail in the following subsections in addition to their attributes. Thus, the assessment file framework for selecting a wealth management bank is a system that incorporates causal relationships between influencing variables. The components that influence wealth management bank selection are complex that latent information is more reliable than apparent information.

Wealth management can assist high net worth securely and create wealth. This progressed speculation counseling involves money, speculation, costs, and cash flow and obligation management based on client needs. This section discusses the variables utilized for the execution assessment, detailing the sub-factors that influence most components and the assessment criteria created therefrom. Moreover, this section identifies the persuasive components vital to wealth management bank selection according to the literature and examines the gaps. A coordinated plan and assessment strategy was developed to select the ideal bank. The leveled decision-making structure comprises four traits, which are discussed in detail in the following.

2.1. Wealth Bank Image Perspective

The wealth bank image perspective can be classified into three categories: reputation, market share, and the degree of internationalization.

2.1.1. Reputation

Corporate image has recently been controversial in monetary trade [7,8,9,10,11]. Corporate image is a vital intangible resource that empowers firms to establish client connections [12] as it influences clients’ decisions on whether to use them in management. Thus, image is imperative to benefit companies with overwhelmingly intangible items [13,14,15,16]. A great reputation is broadly respected, facilitating the recruitment and retention of qualified representatives, a favorable treatment by stock advertising investigators and the media, superior relationships with directing offices, the ability to barter with source/vendor/partner/distributor systems, and a saleable brand [17,18,19,20].

2.1.2. Market Share

Market share is calculated as the company’s bargains over a period over the general industry bargains over that same period [21,22,23]. Market share is used to convey a common thought of the strength of a company compared with its market and competitors [23,24], indicating the rate of general trade volume it controls compared with its competitors. Data regarding a firm’s relative market share, which shows its competitive position, can be combined with data on industry development rate and engaging quality to determine the best future positioning of the firm [25,26]. Industry attractiveness is determined by examining the industry focusing on the weaknesses and opportunities confronting competitors [27]. Industry development rate is determined by measuring the patterns of client investment levels [21,28].

2.1.3. Degree of Internationalization

Firms increase their degree of internationalization as they expand their operations overseas because they involve increased execution levels [29,30,31,32]. The degree of internationalization is measured in terms of the share of add-on deals, resources, salary, and workers exterior to a company’s home country. Internationalization allows firms to identify most household markets through their experience in universal campaigns, hence moving forward to execution [33,34,35,36,37].

2.2. Customer Service Perspective

Service attitude, professional consultation services, and additional services must be considered when selecting the ideal wealth management bank.

2.2.1. Service Attitude

A perfect trade significantly depends on developing a positive behavior and giving esteem to others [38,39,40]. Firms determine a requirement and supply its arrangement rather than concentrating on the money-related perspective [41,42,43]. As a result, they exceed the client’s expectations without further actions [44,45,46]. When benefit corporations participate, show concern, and provide assistance, they can win clients permanently [47,48,49].

2.2.2. Professional Consultation Service

Proficient administration provides clients with programs planned particularly for lawyers, paralegals, and other legitimate experts [50,51]. Such improvement programs comprise on-site courses, gatherings, conferences, addresses, and other groups that provide proceedings legitimate credit instruction [52,53]. These helpful, cost-effective, authorized courses are conducted by an experienced group of trusted lawyers and subject matter specialists [54].

2.2.3. Additional Services

Extra services include budgeting, credit, bequest planning, retirement arrangements, college subsidies, common venture subjects, and assessment issues [55,56].

2.3. Business Process and Product Perspective

The trade process viewpoint should be considered to meet the requirements of the wealth bank image and client benefit perspectives of selecting the ideal wealth management bank.

2.3.1. Financial Instrument Diversification

Diversification can reduce risks by distributing speculations to different monetary control, businesses, and other categories [57,58]. Thus, return is maximized by contributing to several zones that would respond unexpectedly at the time [59]. Most investment experts concur that broadening is the foremost critical component of achieving long-term budgetary objectives that minimize risk, though it does not ensure protection against financial misfortune [60,61].

2.3.2. Transaction Safety

Transaction security has increasingly become critical with the rise of online account management and shopping that empower the utilization of checking and credit card data, [62,63]. The Internet has developed different online installment modes [64]. Thus, online clients and users become incapable when trading data have no appropriate encryption innovation or security measures. Online exchanges often occur faster than using a standard credit card or checking account. Preventative actions are vital to guaranteeing online security as providing individual online information poses various risks [65,66].

2.3.3. Transaction Mode Diversification

Exchange mode diversification can help clients oversee chance and diminish the instability of asset development cost [67] considering that risk cannot be completely identified regardless of how expanded a clients’ portfolio. Risks related to individual stocks can be diminished, though commonly known risks influence each stock; thus, expanding diverse resource classes is critical [68,69]. The key is to determine the balance between risk and return, thereby guaranteeing that clients accomplish their money-related objectives without problems [70,71].

2.4. Managers’ Learning and Growth Perspective

Managers’ learning and development perspectives can be separated into three categories: professional financial competence, educational background and training, and previous successful experiences.

2.4.1. Professional Financial Knowledge

Knowledge about customers’ common capacity and competency reflects their intellectual capabilities and capacities [72,73]. Knowledge is multidimensional and characterized by budget directors’ capacity to hone securely and successfully, satisfying their proficient obligation inside the managers’ scope of expertise [74,75].

2.4.2. Educational Background and Training

Educational background is one of the foremost vital assessment criteria for financial supervisors’ capabilities [76]. A careful examination of educational background will gather job-related data about an individual’s past behavior, experience, instruction, execution, and other critical components and will determine the candidate’s best qualification as a budget director if used along with other screening criteria [77]. Managers’ educational background can influence financial specialists who select to seek after an execution degree at the next instruction institution rather than preparing at proficient private studios [78].

2.4.3. Previous Success

An individual with proficient experience could be a highly intellectual specialized director with an incredible understanding and remarkable execution qualities [79].

The above-mentioned theoretical models expand our understanding of wealth management bank selection factors. These studies discuss a set of potentially relevant factors for wealth management bank evaluation. This present research develops a decision-making process model for wealth management bank selection. In this study, we propose a wealth management bank selection system. We present the wealth management bank selection criteria using the MCDM approach. This strategy incorporates a few procedures that allow rating numerous criteria and then positioning them with the suppositions of specialists.

We examined six wealth management banks in Taiwan: three international banks and three local banks:

- Bank 1 is a popular international US bank and the buyer managing a pioneer account in financial services. It operates in more than 100 countries worldwide. In addition to maintaining standard money exchanges, the bank offers protections, credit cards, and speculation items. Their online service division is among the most successful within the field. Thus, this bank has been the leader and pioneer in wealth management in Taiwan.

- Bank 2 is a prestigious European bank with worldwide operations and organized into four trades: commercial account managing, keeping money and markets internationally, personal financial services (retail keeping money and buyback), and global private banking. This bank is more popular among locals in the Asia-Pacific than other non-Asian banks.

- Bank 3 is a rapidly developing Australian bank and is one of the thriving international banks after merging with other European banks. This bank has been highly active in Taiwan, with its trade centered on high-end clients and providing innovative services.

- Bank 4 offers different items and administration in addition to experienced staff committed to ensuring the success of their customers’ ventures. It offers clients diverse options for keeping monetary items to meet the monetary needs of individuals and families.

- Bank 5 has been established over the past 50 years from property and casualty safety net providers into a supplier of various financial, real estate, telecommunications, and media segments. It has also extended its commerce to China.

- Bank 6 is a creative bank in Taiwan that primarily provides inventive administrations, such as ATMs in 7–11 convenience stores in Taiwan.

In sum, the above-mentioned theoretical models expand the understanding of wealth management bank selection factors. These studies focus on a set of potentially relevant factors for wealth management bank evaluation. This present research proposes the TOPSIS and fuzzy theory as the main analytical tool. The fuzzy TOPSIS is a framework with expert information and a comprehensive tool used to portray the structures of complex relations. This strategy selects the intelligence between components agreeing to their particular characteristics and changes the causality of the variables to a precise basic system. The fuzzy TOPSIS approach has advantages including the evaluation of the cause and effect analysis, considering the fuzziness condition, and dealing flexibly with the fuzziness situation. This diagraph is a useful tool that serves as a guide for the top management to identify the course of actions necessary for the Taiwan wealth management bank. This section presents an empirical study to illustrate how wealth management bank selection is applied to enhance banks’ advantage.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with specialists to develop the survey system and thus understand wealth management comprehensively. Such interviews provide rich information that empowers subject matter specialists to share information in a casual setting. Below, we discuss the research method in detail, namely, the fuzzy TOPSIS.

3. Expert Interview

We collected usable measurements and criteria from the writing audit for the wealth management bank assessment and selection. These measurements and criteria were screened to determine the most reasonable and appropriate ones [80,81]. As a result, four measurements and 14 criteria were used [82,83]. Eight specialists who worked in commercial banks and as financial and marketing professors were interviewed. They are familiar with wealth management banks and are directly or indirectly concerned with wealth management (Table 1). The interviews were conducted in their place of work in Taichung City and Changhua City in Taiwan.

Table 1.

Major proposal to assessment system from the expert meeting.

These interviews were used to accumulate expert suppositions on wealth management banks, analyze wealth management variables, and balance these variables to impact wealth management bank selection. This paper progressively illustrates the specialists’ organizations and meeting topics to supply fundamental data, summarize the experts’ fundamental conclusions on all topics, and classify the findings into four fundamental categories for the subsequent survey. These experts designed the assessment and selection model based on the information provided and their wealth management experience from a mechanical perspective [81,84]. The proposed system incorporates three measurements and 12 assessment criteria as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Wealth management bank evaluation framework.

4. Fuzzy TOPSIS Method

This research also illustrates the advantages of TOPSIS research methods and integrates past research on the application of these methods. In addition, the analysis and discussion of financial management in past studies depend on a single aspect and factor. This research uses an integrated research method to analyze and propose four major aspects and 12 factors for wealth management bank evaluation. This research applies the integrated model to provide a comprehensive and complete policymaking reference for future industrial policymakers to construct a suitable strategy for financial industrial development.

Individuals frequently consider the relative significance of each evaluation factor in the preparation of the MCDM on execution assessment. The foremost coordinated and straightforward strategy is to assign weights to each variable. This study utilized the fuzzy TOPSIS weight coefficient strategy and examined and processed subjective information. Lin and Chang [84] arranged manufacturer (provider) choice and estimate with make-to-order premise when orders surpass the generation capacity. Chen and Tsao [85] developed choice examination based on interval-valued fuzzy sets. In contrast, Ashtiani et al. [86] utilized interval-valued fluffy sets concepts. Mahdav et al. [87] outlined perfect arrangements. Büyüközkan et al. [88] distinguished the vital fundamental accomplice choice that companies consider the foremost imperative and accomplish the ultimate partner-ranking. Kahraman et al. [89] proposed a model for mechanical frameworks. Benítez et al. [90] assessed the service quality of three inns of an important enterprise in Gran Canaria through overviews.

The proposed strategy was used to assess the criteria for wealth management bank selection and rank them according to their importance [91,92]. The TOPSIS is characterized by the comparability to a positive–ideal course of action and the remoteness from a negative–ideal course of action [93,94,95,96,97,98,99]. This strategy is appropriate for understanding the decision-making issue in a fuzzy environment. The fuzzy TOPSIS method was based on the concept of Ashtiani et al. [86] and Büyüközkan et al. [96] with the following stages.

Stage 1: Calculate the weights of the appraisal criteria.

An effective approach to increasing the TOPSIS is proposed to understand the estimation of clusters of action in a fuzzy environment in this region. The weights of diverse criteria and the assessments of subjective criteria are considered as etymological variables [97,98,99].

Stage 2: Construct the fuzzy decision-making framework as follows [100,101,102,103,104,105,106]:

Stage 3: Calculate the normalized matrix.

We can apply the following equation to obtain the normalized matrix:

Stage 4: Calculate the fuzzy positive–ideal arrangement (FPIS) and fuzzy negative–ideal arrangement (FNIS) as follows:

where , , and .

Stage 5: Calculate each estimation from FPIS and FNIS.

The separations ( and ) of all measurements can be calculated by the regional emolument strategy as follows:

Stage 6: Obtain the closeness coefficient, and rank banks 1–6.

Calculate similitudes to a perfect arrangement using Equation (8) below. The position of all choices is determined, thus determining leading choice as follows:

5. Empirical Study

Figure 1 illustrates the total progression of selecting the wealth management bank.

Stage 1: Determine the linguistic weighting of each measurement.

The interviews were conducted in the winter of 2011. Then, the survey was sent to 28 specialists, eight of whom did not complete the survey and thus were not included in this article [107,108,109,110]. The COA strategy was applied to compute the importance of the fuzzy weights of each measurement (Table 2).

Table 2.

Linguistic numbers for the significance of each measure.

For example, the importance of the weight of C1 (reputation) was calculated as follows:

We calculate each factor weighting: reputation (0.723), market share (0.507), the degree of internationalization (0.577), service attitude (0.762), professional consultation service (0.807), additional services (0.557), financial instrument diversification (0.488), transaction safety (0.842), transaction mode diversification (0.577), professional financial knowledge (0.825), educational background and training (0.615), and previous successful experiences (0.595). From the fuzzy TOPSIS, the two primary critical factors for a wealth administration bank are transaction safety (0.842) and professional financial knowledge (0.825) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Weights of criteria.

Stage 2: Assess the performance.

The factors were measure in linguistic terms (Table 2) as “very low,” “low,” “medium,” “high,” and “very high” for each bank (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subjective cognition results of evaluators in linguistic terms.

Stage 3: Calculate the normalized matrix.

We can adopt Equation 2 to calculate the normalizing matrix (Table 5).

Table 5.

Normalized fuzzy decision-making matrix.

Stage 4: Construct the weighted normalized fuzzy evaluation framework.

The weighted normalized fuzzy evaluation framework was then calculated as in Table 6.

Table 6.

Weighted normalized fuzzy decision-making matrix.

Stage 5: Determine the fuzzy positive and negative reference foci as follows:

Stage 6: Assess the execution and positioning of the wealth management banks.

The closeness coefficients of each choice and calculation were utilized as follows:

The value of alternative 1 is obtained as follows:

Table 7 below presents the wealth management bank assessment.

Table 7.

Closeness coefficients and ranking.

6. Conclusions

The wealth management bank selection involves numerous associated factors. A case study of wealth management banks selecting the most appropriate wealth bank was applied to illustrate the proposed crossover strategy. This strategy provides insights into and proposals for wealth management bank assessment and selection.

The field of wealth management bank evaluation remains relatively new, though it has developed rapidly over the last decade [112,113,114,115,116,117,118]. The MCDM approach, particularly the fuzzy TOPSIS, was used to develop a survey to assess and determine the most appropriate wealth management bank. Financial specialists can communicate their data with practical composing and presentation capacities [41,45,119]. The personal skills required to succeed as a financial advisor involve understanding distinctive identity types, participating, asking appropriate questions, settling clashes, teaching others, and counseling clients. Financial specialists assist clients to succeed when they rely on wealth management directors, such as wealth management supervisors, and observe that wealth management managers regard them. Financial experts should showcase their proficient abilities and knowledge to gain prospects in their specialized markets and thus understand individuals’ qualities and wealth administration banks’ proficient qualities [42].

Many are concerned about their fund management during the current pandemic. Numerous questions have been raised on whether credit card companies should charge current installments or waive late payments for a few months, how to plan for the next financial year during this questionable financial situation, or where to keep savings in this uncertain situation. People have to restart and expect sound financial assistance exists. Wealth bank determination involves numerous associated factors. Numerous companies focus on emolument and disregard approximately benefit. To maintain movement between benefit corporations and their clients, benefit corporations must continually learn.

The two primary aspects of wealth bank evaluation are transaction safety and professional financial knowledge. Directors must productively and viably manage time, manage budgets, meet due dates, and gain advantages from other individuals to perform effectively. Moreover, although supervisors continuously experience work issues, they must resolve and examine such issues beyond and above their duties. Directors must be knowledgeable about computer equipment and work-related programs and use them immediately. A competitive identity and enthusiasm are significant to success. Clients expect wealth management supervisors to assist them in managing their wealth to serve their family’s long-term needs. Thus, managers ought to beneficially and reasonably arrange time, oversee budgets, meet due dates, and gain advantages from other individuals [46]. Wealth management supervisors continuously experience and overcome issues, with wealth management managers going beyond their obligations. Wealth management supervisors must be knowledgeable about computer equipment and programs, regardless of where directors work [44,48].

Security is the most important factor in Internet exchange. In reality, a web exchange is likely more secure than an over-the-counter and over-the-phone card exchange. The reason is that the data transmitted online are profoundly disarranged through complicated logarithm combinations. Transfer of purchase details from the retailer’s site to that of the wealth management bank is encapsulated using an encrypted digitally signed protocol.

Diversification can diminish risks by distributing speculations among different monetary control, businesses, and other categories [61]. Most investment experts concur that enhancement is the most vital component of long-term money-related items that minimize risks though it does not ensure protection against misfortune [60]. Security is one of the most important concerns for the customer and retailer in Internet exchange [64]. The exchange of discreet purchase information from the retailer’s location to that of the wealth management bank is encrypted with disarranged and digitally signed conventions.

Supervisors continuously experience issues that allow them to understand such issues rather than experiencing burnout. Moreover, wealth supervisors going beyond their responsibilities is favorable. Directors must be knowledgeable about computer equipment and programs and selecting modern work-related programs rapidly. Investors select based on work experience because they expect experienced financial managers to perform well. Managers often use their past experiences as a convenient intermediary for information and aptitude that contributes to execution. Past work experiences can influence propensities, schedules, and other cognitions and behaviors that may not be valuable for performance when connected in a distinctive setting. Past work experience may promote execution, though indirectly through significant information and expertise. The reason is that past work experience enables individuals to obtain important information.

In conclusion, speculators select based on work experience because they anticipate experienced financial supervisors to perform well. Previous work experience can influence propensities, schedules, and other cognitions and behaviors that may not be valuable for execution when connected in a distinctive setting. Work experience may promote execution, though indirectly through significant information and ability. The reason is that previous work experience enables individuals to obtain significant knowledge and aptitudes that can improve execution. Future research should investigate how to improve the model and analyze the complex relationships between these assessment measurements. Thus, the most imperative criteria conjointly measuring the relationships between these assessment criteria can be recognized. Based on the major competencies of the TOPSIS strategy, directors can successfully increment the competitive advantage of wealth administration banks. This strategy enables financial specialists to diminish the impedances and much data among various persuasive variables utilizing expert information. Thus, future researchers can provide a reference for analysts to develop determination social models.

Interest in discoveries may shift from one nation to another as diverse businesses have outstanding contrasts. Moreover, this study presents limitations in terms of the short test estimate. Future investigations can be conducted to test the selection variables in this study and consider utilizing diverse strategies and bigger test sizes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-C.S.; formal analysis, C.-C.S.; investigation, C.-C.S.; methodology, C.-C.S.; project administration, C.-C.S.; resources, C.-C.S.; software, C.-C.S.; supervision, C.-C.S.; validation, C.-C.S.; visualization, C.-C.S.; writing—original draft, C.-C.S.; writing—review and editing, C.-C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gao, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.F.; Shen, W.; Yeung, S. Web-service-agents-based family wealth management system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2005, 29, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.R.; Lin, C.T.; Tsai, P.H. Evaluating business performance of wealth management banks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 207, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, M.; Frutos, M.; Miguel, F.; Aguasca-Colomo, R. TOPSIS Decision on Approximate Pareto Fronts by Using Evolutionary Algorithms: Application to an Engineering Design Problem. Mathematics 2020, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, F. A Model for Evaluating the Influence Factors in Trademark Infringement Based on Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 38, 6777–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.W.; Lo, H.W.; Chen, K.Y.; Liou, J.J.H. A Novel FMEA Model Based on Rough BWM and Rough TOPSIS-AL for Risk Assessment. Mathematics 2019, 7, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acunto, M.; Martinelli, M.; Moroni, D. From Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells to Osteosarcoma Cells Classification by Deep Learning. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 37, 7199–7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotha, S.; Rajgopal, S.; Rindova, V. Reputation Building and Performance: An Empirical Analysis of the Top-50 Pure Internet Firms. Eur. Manag. J. 2001, 19, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.M.; Abratt, R.; Dion, P. The influence of retailer reputation on store patronage. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2006, 13, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Hogg, T. Reputation mechanisms in an exchange economy. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić-Hodović, V.; Mehić, E.; Arslanagić, M. Influence of Banks’ Corporate Reputation on Organizational Buyers Perceived Value. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mitra, R. Framing the corporate responsibility-reputation linkage: The case of Tata Motors in India. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuki, H.; Iwasa, Y. How should we define goodness-reputation dynamics in indirect reciprocity. J. Theor. Biol. 2004, 231, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelissen, J.; Thorpe, R. Measuring a Business School’s Reputation: Perspectives, Problems and Prospects. Eur. Manag. J. 2002, 20, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravens, K.; Oliver, E.G.; Ramamoorti, S. The Reputation Index: Measuring and Managing Corporate Reputation. Eur. Manag. J. 2003, 21, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravens, K.S.; Oliver, E.G. Employees: The key link to corporate reputation management. Bus. Horiz. 2006, 49, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nakao, A. Poisonedwater: An improved approach for accurate reputation ranking in P2P networks. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2010, 26, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, T.G.; Stamoulis, G.D. Reputation-based policies that provide the right incentives in peer-to-peer environments. Comput. Netw. 2006, 50, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.; Garnefeld, I.; Tolsdorf, J. Perceived corporate reputation and consumer satisfaction—An experimental exploration of causal relationships. Australas. Mark. J. 2009, 17, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.; Salminen, R.T. Basking in reflected glory: Using customer reference relationships to build reputation in industrial markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolitzky, A. Indeterminacy of reputation effects in repeated games with contracts. Games Econ. Behav. 2011, 73, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Farris, P.W.; Parry, M.E. Market share and ROI: Observing the effect of unobserved variables. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1999, 16, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Ikenberry, D.L.; Lee, I. Do managers time the market? Evidence from open-market share repurchases. J. Bank Financ. 2007, 31, 2673–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, B.D.; Chan, F.; McAleer, M. Evaluating the impact of market reforms on Value-at-Risk forecasts of Chinese A and B shares. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2008, 16, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uncles, M.D.; East, R.; Lomax, W. Market share is correlated with word-of-mouth volume. Australas. Mark. J. 2010, 18, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSarbo, W.S.; Degeratu, A.M.; Ahearne, M.J.; Saxton, M.K. Disaggregate market share response models. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2002, 19, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, R.A. Strategic incentives for market share. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2008, 26, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, P.J. Comparing naive with econometric market share models when competitors’ actions are forecast. Int. J. Forecast. 1994, 10, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mixon, F.G., Jr.; Hsing, Y. The determinants of market share for the dominant firm’ in telecommunications. Inf. Econ. Policy 1997, 9, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi-Belkaoui, A. The effects of the degree of internationalization on firm performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 1998, 7, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi-Belkaoui, A. The degree of internationalization and the value of the firm: Theory and evidence. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 1999, 8, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockaitis, A.I.; Vaiginienė, E.; Giedraitis, V. The internationalization efforts of lithuanian manufacturing firms-strategy or luck. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2006, 20, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, P.; Roh, J. Internationalization, product development and performance outcomes: A comparative study of 10 countries. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2009, 23, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, N. Internationalization and performance of small- and medium-sized enterprises. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Pereira, A. Internationalization and performance: The moderating effects of organizational learning. Omega 2008, 36, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granstrand, O. Internationalization of corporate R&D: A study of Japanese and Swedish corporations. Res. Policy 1999, 28, 275–302. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, M.P.; Servais, P. Analyzing internationalization configurations of SME’s: The purchaser’s perspective. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2007, 13, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafouros, M.I.; Buckley, P.J.; Sharp, J.A.; Wang, C. The role of internationalization in explaining innovation performance. Technovation 2008, 28, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Park, Y. A prediction model for success of services in e-commerce using decision tree: E-customer’s attitude towards online service. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 33, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O. Psychological model based attitude prediction for context-aware services. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 2477–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, E.; Basil, D.Z.; Yanamandram, V.; Daroczi, Z. The impact of pre-existing attitude and conflict management style on customer satisfaction with service recovery. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.; Wang, K. Knowledge, attitude and practice survey on immunization service delivery in Guangxi and Gansu. China Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, A.M.; Borchgrevink, C.P.; Kacmar, K.M.; Brymer, R.A. Customer service employees’ behavioral intentions and attitudes: An examination of construct validity and a path model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 19, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A.L.; Han, H. Understanding mobile data services adoption: Demography, attitudes or needs. Technol. Forecast Soc. Chang. 2005, 72, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culpan, O. Attitudes of end-users towards information technology in manufacturing and service industries. Inf. Manag. 1995, 28, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultek, M.M.; Dodd, T.H.; Guydosh, R.M. Attitudes towards wine-service training and its influence on restaurant wine sales. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S.C.; Webber, S.S. Effects of Service Provider Attitudes and Employment Status on Citizenship Behaviors and Customers’ Attitudes and Loyalty Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzeng, G.H.; Chiang, C.H.; Li, C.W. Evaluating intertwined effects in e-learning programs: A novel hybrid MCDM model based on factor analysis and DEMATEL. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 32, 1028–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Noyes, J. An assessment of the influence of perceived enjoyment and attitude on the intention to use technology among pre-service teachers: A structural equation modeling approach. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Khan, M.S.; Ashill, N.J.; Naumann, E. Customer attitudes of stayers and defectors in B2B services: Are they really different. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, C.; Entwistle, V.A.; Watt, I.S. The significance for decision-making of information that is not exchanged by patients and health professionals during consultations. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2065–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, C.E.; Laviolette, G.T.; Lineman, J.M. Training Professional Psychologists in School-Based Consultation: What the Syllabi Suggest. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2010, 4, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, S.A. Segmenting a business market for a professional service. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1986, 15, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, J.; Barrutia, J.; Lertxundi, A. Hybrid Delphi: A methodology to facilitate contribution from experts in professional contexts. Technol. Forecast Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 1629–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggers, J.H.; Sanson-Fisher, R. Duration of general practice consultations: Association with patient occupational and educational status. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Guo-sun, Z.; Liang, Z. Additional service security of e-commerce in mine enterprises. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2009, 1, 1574–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, S.; Weerawardena, J.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. Towards a model of dynamic capabilities in innovation-based competitive strategy: Insights from project-oriented service firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, L.; Levine, R. Is there a diversification discount in financial conglomerates. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 85, 331–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, J.; McKillop, D.; Wilson, J.O.S. The diversification and financial performance of US credit unions. J. Bank Financ. 2008, 32, 1836–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.B.; Pantzalis, C.; Park, J.C. Corporate use of derivatives and excess value of diversification. J. Bank. Financ. 2007, 31, 889–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercieca, S.; Schaeck, K.; Wolfe, S. Small European banks: Benefits from diversification. J. Bank. Financ. 2007, 31, 1975–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. Dependence structure of risk factors and diversification effects Insurance. Math. Econ. 2010, 46, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.J. The antecedents and consequences of trust in online-purchase decisions. J. Interact. Mark. 2002, 16, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.H.; Lee, W.S. Finding recently frequent itemsets adaptively over online transactional data streams. Inf. Syst. 2006, 31, 849–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleist, V. A Transaction Cost Model of Electronic Trust: Transactional Return, Incentives for Network Security and Optimal Risk in the Digital Economy. Electron. Commer. Res. 2004, 4, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.J.; Lee, M.C. Improving WTLS Security for WAP Based Mobile e-Commerce. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2009, 51, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, S.N.; Fanti, K.A. A transactional model of bullying and victimization. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2010, 13, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Jang, S.C. Effect of diversification on firm performance: Application of the entropy measure. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.E.; Kiymaz, H.; Perdue, G. Portfolio diversification in a highly inflationary emerging market. Financ. Serv. Rev. 2001, 10, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z. Firm diversification and the value of corporate cash holdings. J. Corp. Financ. 2011, 17, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. Diversification of risk and saving. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2003, 43, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, Y.; Ushijima, T. Corporate diversification, performance, and restructuring in the largest Japanese manufacturers. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2007, 21, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shae, Z.Y.; Wang, X.; Kaenel, J.V. Transactional Multimedia Banner as Web Access Point. Electron. Commer. Res. 2001, 1, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. Electronic Monitoring to Promote National Security Impacts Workplace Privacy. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2003, 15, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, H.G. Relationship of early work challenge to job performance, professional contributions, and competence of engineers. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah, G.B. A professional services firm’s competence development. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 1068–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJaeghere, J.G.; Cao, Y. Developing U.S. teachers’ intercultural competence: Does professional development matter. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2009, 33, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Birkett, B. Managing intellectual capital in a professional service firm: Exploring the creativity–productivity paradox. Manag. Account. Res. 2004, 15, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baartman, L.K.J.; Bruijn, E.D. Integrating knowledge, skills and attitudes: Conceptualising learning processes towards vocational competence. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Gale, A.; Brown, M.; Kidd, C. The development and delivery of an industry led project management professional development programme: A case study in project management education and success management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2008, 26, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkemeyer, B.; Januszewski, N.; Julstrom, B.A. An expert system for evaluating Siberian Huskies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2006, 30, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cay, T.; Iscan, F. Fuzzy expert system for land reallocation in land consolidation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 11055–11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagradjanin, N.; Pamucar, D.; Jovanovic, K. Cloud-Based Multi-Robot Path Planning in Complex and Crowded Environment with Multi-Criteria Decision Making Using Full Consistency Method. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, M.; Baudrit, C.; Leclerc-Perlat, M.N.; Wuillemin, P.H.; Perrot, N. Expert knowledge integration to model complex food processes: Application on the camembert cheese ripening process. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 11804–11812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.; Chang, W.L. Order selection and pricing methods using flexible quantity and fuzzy approach for buyer evaluation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 187, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Y.; Tsao, C.Y. The interval-valued fuzzy TOPSIS method and experimental analysis. Fuzzy Sets. Syst. 2008, 159, 1410–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtiani, B.; Haghighirad, F.; Makui, A.; Montazer, G.A. Extension of fuzzy TOPSIS method based on interval-valued fuzzy sets. Appl. Soft Comput. 2009, 9, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, I.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N.; Heidarzade, A.; Nourifar, R. Designing a model of fuzzy TOPSIS in multiple criteria decision making. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 206, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G.; Feyzioğlu, O.; Nebol, E. Selection of the strategic alliance partner in logistics value chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2007, 113, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, C.; Çevik, S.; Ates, N.Y.; Gülbay, M. Fuzzy multi-criteria evaluation of industrial robotic systems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2007, 52, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, J.M.; Martín, J.C.; Román, C. Using fuzzy number for measuring quality of service in the hotel industry. Tour Manag. 2007, 28, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinçer, H.; Yüksel, S.; Martínez, L. Interval type 2-based hybrid fuzzy evaluation of financial services in E7 economies with DEMATEL-ANP and MOORA methods. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 79, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, R.; Allen, J.K.; Mistree, F. Managing computational complexity using surrogate models: A critical review. Res. Eng. Des. 2020, 31, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, D.; Arsovski, S.; Aleksic, A.; Stefanovic, M.Z. A fuzzy evaluation of projects for business processes’ quality improvement. In Intelligent Techniques in Engineering Management 2015, 87, 559–579. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, M.K.; Kusakci, A.O.; Tatoglu, E.; Icten, O.; Yetgin, F. Performance evaluation of real estate investment trusts using a hybridized interval type-2 fuzzy AHPDEA approach: The case of Borsa Istanbul. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2019, 18, 1785–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleibari, S.S.; Beiragh, R.G.; Alizadeh, R.; Solimanpur, M. A framework for performance evaluation of energy supply chain by a compatible network data envelopment analysis model. Sci. Iran. 2016, 23, 1904–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, H.Y.; Tzeng, G.H.; Chen, Y.H. A fuzzy MCDM approach for evaluating banking performance based on Balanced Scorecard. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 10135–10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roghanian, E.; Rahimi, J.; Ansari, A. Comparison of first aggregation and last aggregation in fuzzy group TOPSIS. Appl. Math. Model. 2010, 34, 3754–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.H.; Hsu, W. A novel hybrid model based on DEMATEL and ANP for selecting cost of quality model develop-ment. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2010, 21, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Park, I.Y.; Kwun, Y.C.; Tan, X. Extension of the TOPSIS method for decision making problems under inter-val-valued intuitionistic fuzzy environment. Appl. Math. Model. 2011, 35, 2544–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.H.; Hsu, W.; Chou, W.C. A gap analysis model for improving airport service quality. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2011, 22, 1025–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamodrakas, I.; Martakos, D. A utility-based fuzzy TOPSIS method for energy efficient network selection in hetero-geneous wireless networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 3734–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.Y.; Weng, Y.C. A study of supplier selection factors for high-tech industries in the supply chain. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2010, 21, 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; You, X.Y.; Liu, H.C.; Wu, S.M. An Extended VIKOR Method Using Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets and Combination Weights for Supplier Selection. Symmetry 2017, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control. 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Bonsall, S.; Wang, J. Approximate TOPSIS for vessel selection under uncertain environment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 14523–14534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Hung, C.C. Multiple-attribute decision making methods for plant layout design problem. Robot Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2007, 23, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T.; Lin, C.T.; Huang, S.F. A fuzzy approach for supplier evaluation and selection in supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2006, 102, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.S.; Chen, K.Y.; Li, C.Y. Application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process and Grey Relational Analysis for Vendor Selection of Spare Parts Planning Software. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Tzeng, G.H. Creating the aspired intelligent assessment systems for teaching materials. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 12168–12179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Chen, N.; Li, J. During-incident process assessment in emergency management: Concept and strategy. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, H.; Faghih, A.; Fathi, M.R. Fuzzy multi-criteria decision making method for facility location selection. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rouyendegh, B. Developing an Integrated ANP and Intuitionistic Fuzzy TOPSIS Model for Supplier Selection. J. Test Eval. 2015, 43, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lin, C. Evaluating Convention Destination Images in Australia and Asia. J. Test Eval. 2013, 41, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrek, R. An Analysis of Usage of a Multi-Criteria Approach in an Athlete Evaluation: An Evidence of NHL Attackers. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnari, M. The future of meat consumption-Expert views from Finland. Technol. Forecast Soc. Chang. 2008, 75, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Song, L.; Yang, Z. An Evidential Prospect Theory Framework in Hesitant Fuzzy Multiple-Criteria Deci-sion-Making. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.W.; Hsu, C.C.; Huang, C.N.; Liou, J.J.H. An ITARA-TOPSIS Based Integrated Assessment Model to Identify Poten-tial Product and System Risks. Mathematics 2021, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.H.; Hsu, T.S.; Tzeng, G.H. A balanced scorecard approach to establish a performance evaluation and relation-ship model for hot spring hotels based on a hybrid MCDM model combining DEMATEL and ANP. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 908–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M.; Hatami-Marbini, A. A group AHP-TOPSIS framework for human spaceflight mission planning at NASA. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 13588–13603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).