Personalized Cotesting Policies for Cervical Cancer Screening: A POMDP Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

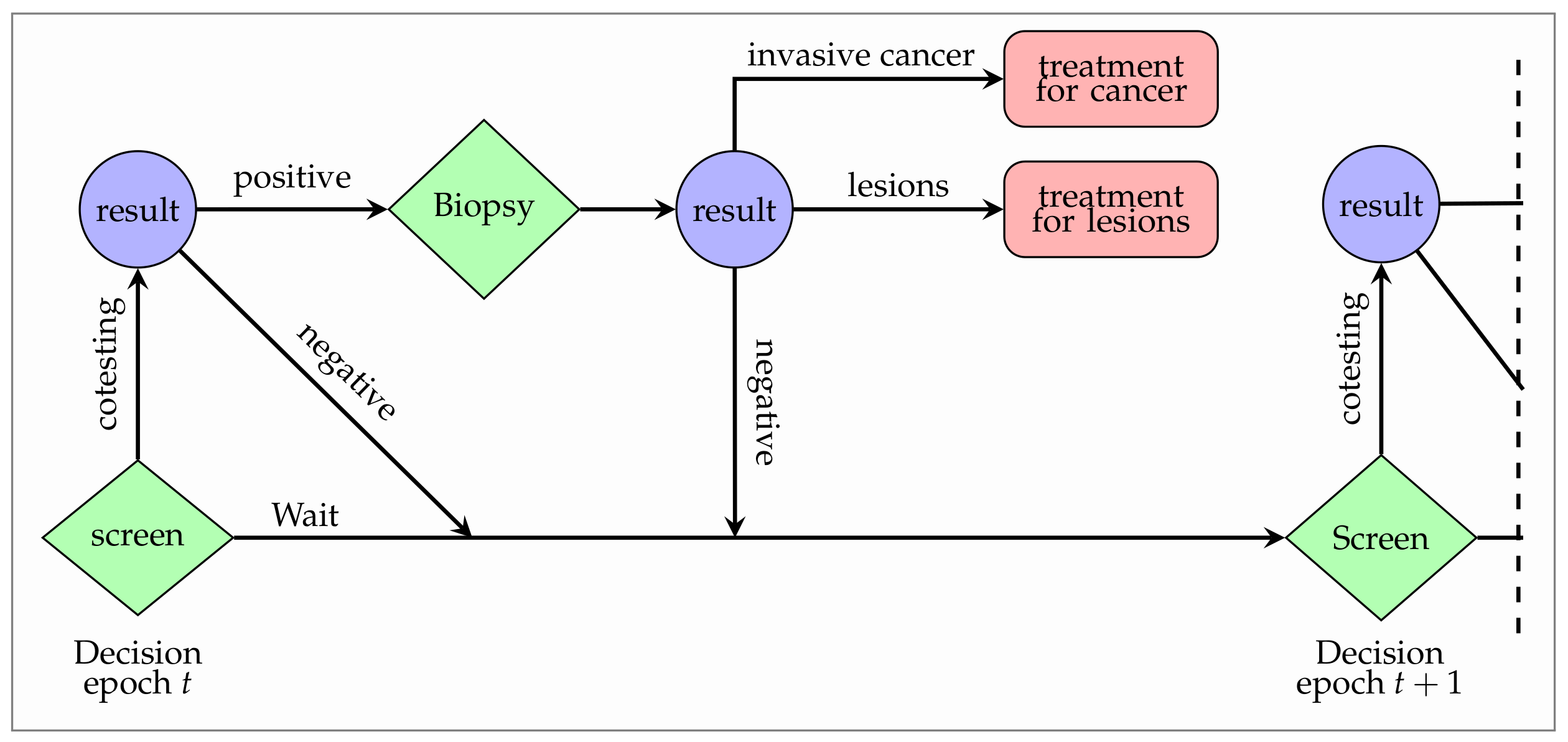

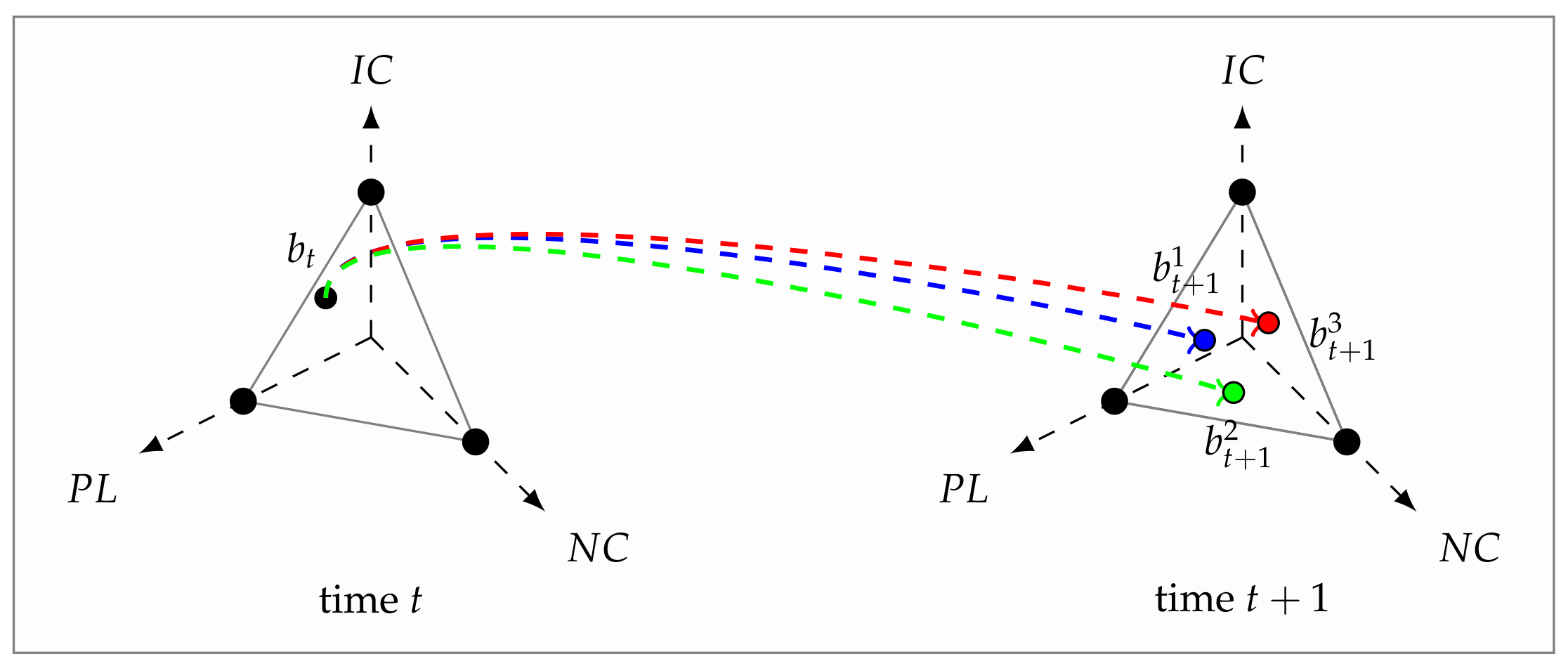

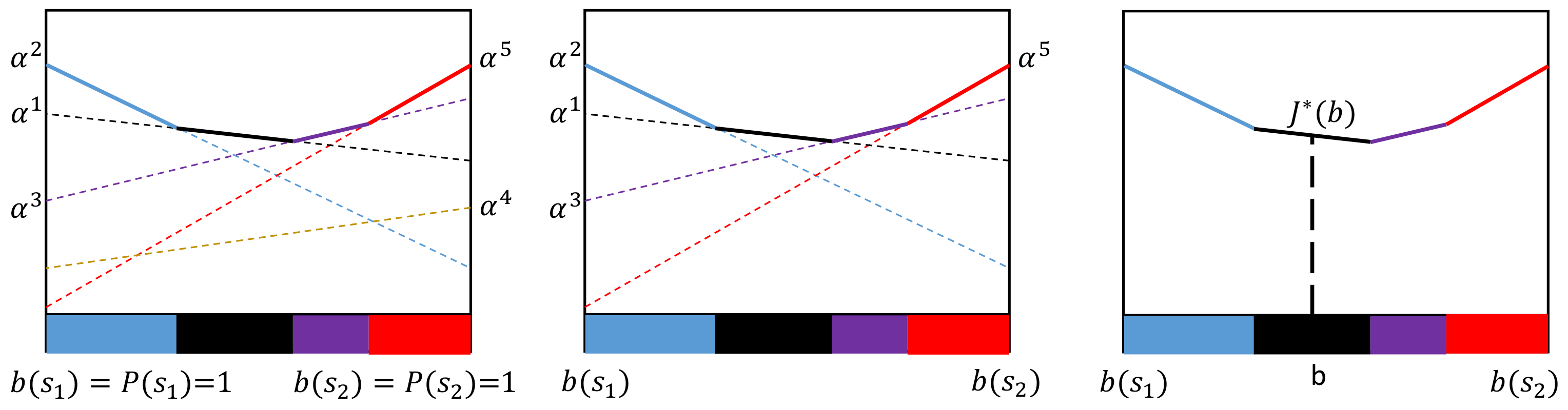

2. Materials and Methods

| Algorithm 1 Compact representation of solution method with Monahan’s algorithms and Eagle’s reduction phase |

|

3. Results

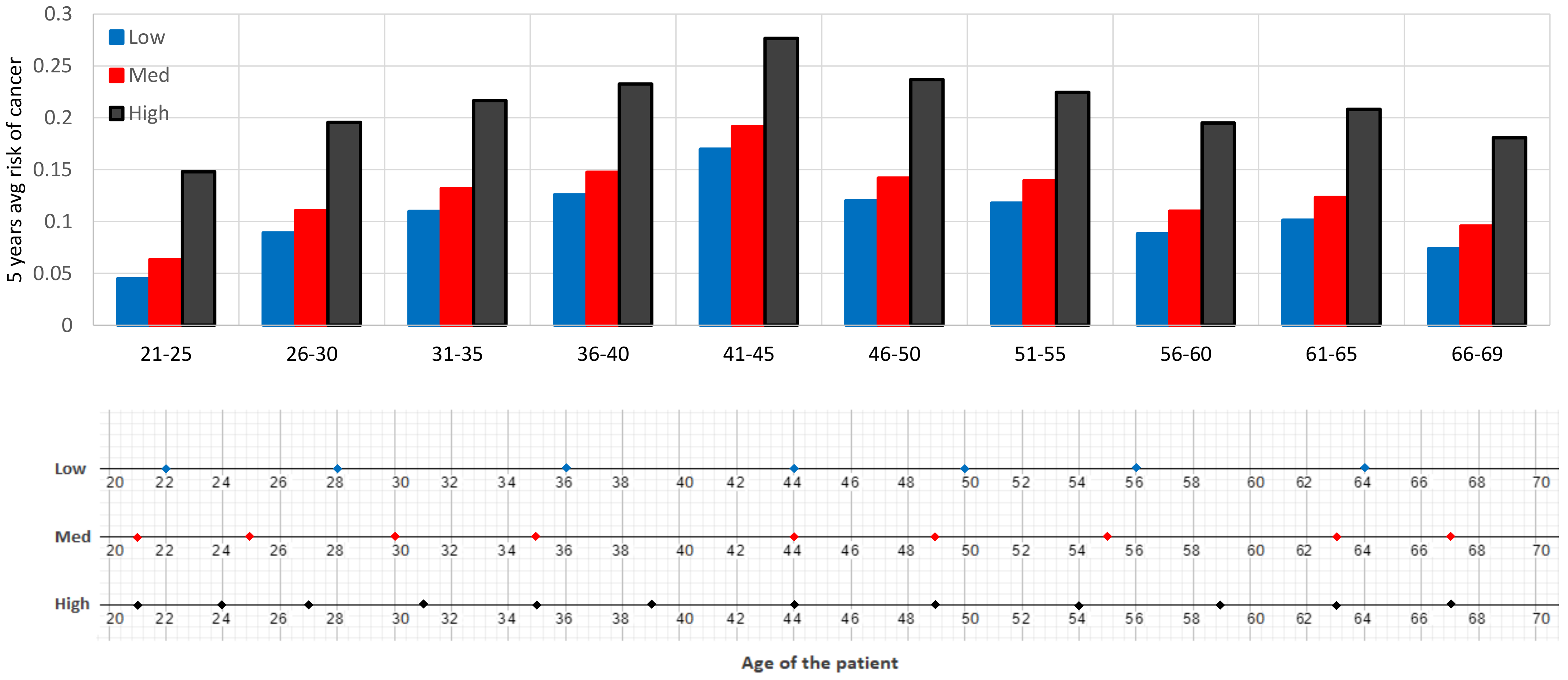

3.1. Optimal Belief-Based Screening Policy

- Low risk patient: ,

- Medium risk patient: ,

- High risk patient: .

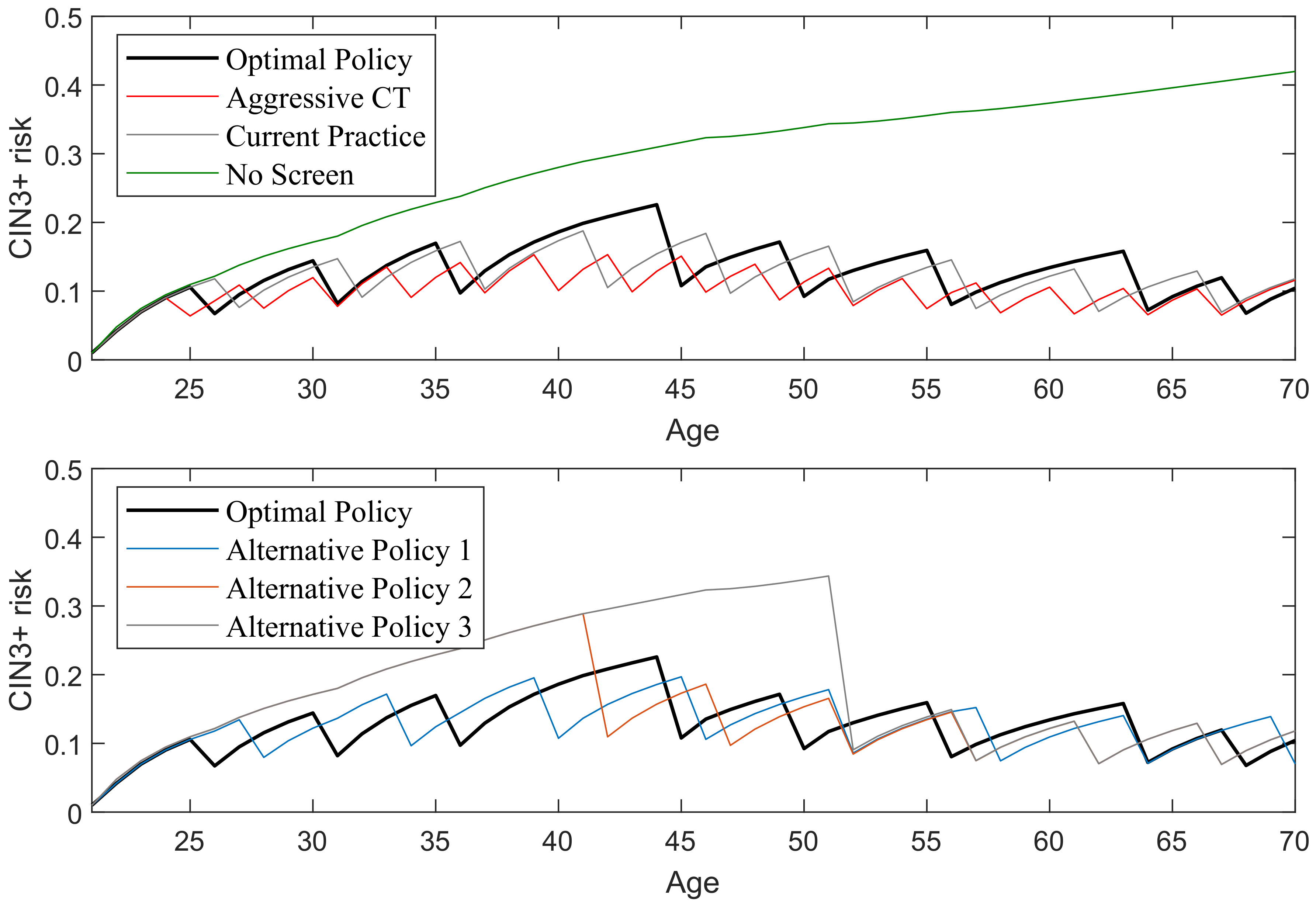

3.2. Comparison of Multiple Policies and Guidelines

3.2.1. QALY-Based Policy Comparison

3.2.2. Comparison of Lifetime Cancer Risk across Different Policies

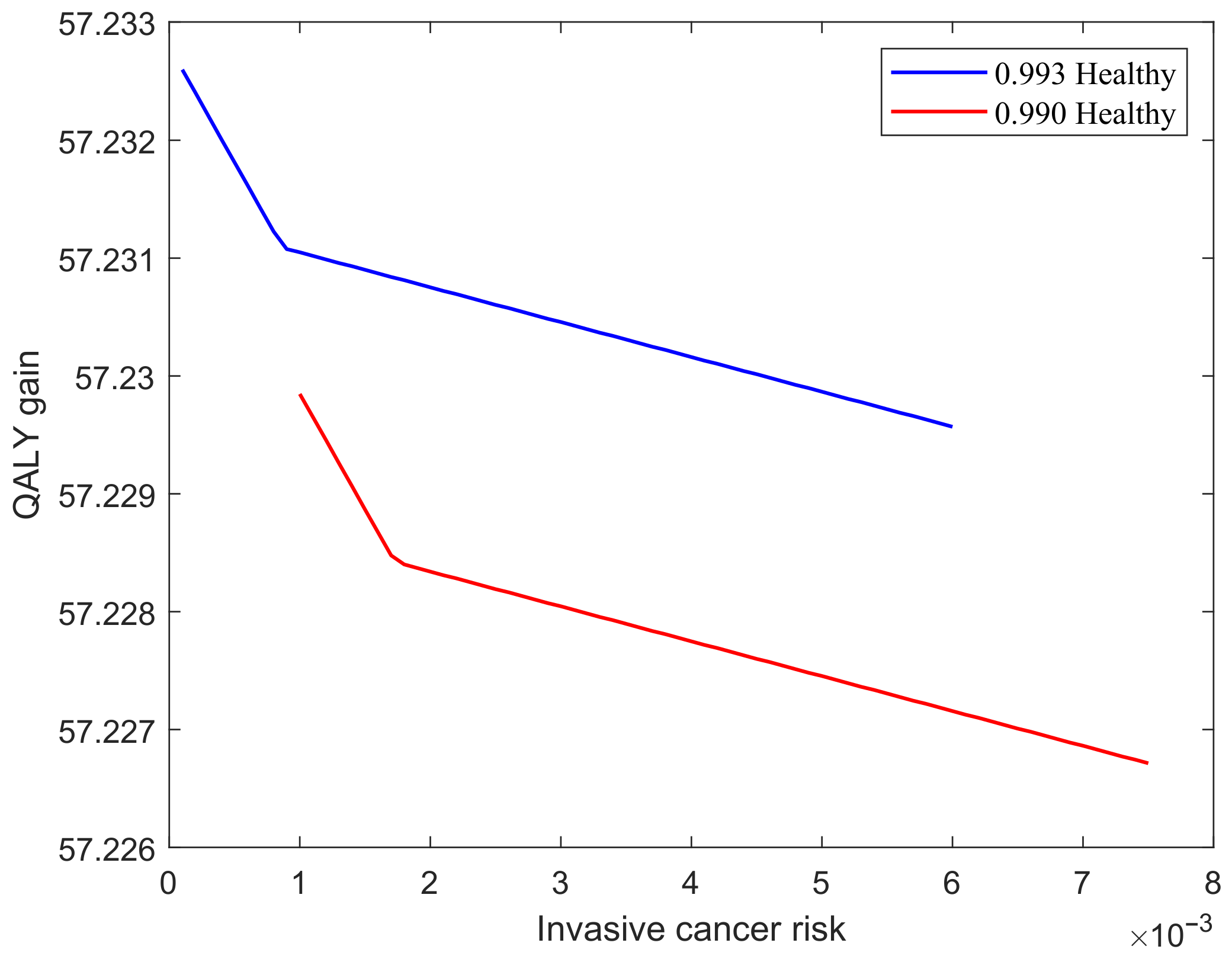

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

- Set 1: high risk patients who are healthy and their invasive cancer risks vary between and . This case is shown with a red line in Figure 7.

- Set 2: medium risk patients who are healthy and their invasive cancer risks vary between and . This case is shown with a blue line in Figure 7.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Sources and Data Collection

| Parameter | Source |

|---|---|

| State transitions | JC et al. [75], Campos et al. [76] |

| Sensitivity and specificity of cotesting | JC et al. [75] |

| Probability of cancerous death | JC et al. [75] |

| Probability of noncancer death | McLay et al. [77] |

| Disutility of Biopsy | Velanovich Velanovich [78], Hanmer et al. [79] |

| Survival rates | SEER data [80] |

| Life expectancy | SEER data [80] |

| Quality of life | US life tables [81] |

| Age Group | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D values | 0.913 | 0.893 | 0.863 | 0.837 | 0.811 | 0.771 | 0.724 |

| Disutility of biopsy (weeks) | 2 | 2.04 | 2.12 | 2.18 | 2.25 | 2.37 | 2.52 |

| Age | Sens(CT,2) | Sens(CT,3) | Specificity CIN3+ Threshold | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| States | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| 21–69 | 0.625 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.375 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.625 | 0.991 | ||

References

- Arbyn, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Bruni, L.; de Sanjosé, S.; Saraiya, M.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: A worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e191–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.A.; Jhingran, A.; Oaknin, A.; Denny, L. Cervical cancer. Lancet 2019, 393, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walboomers, J.M.; Jacobs, M.V.; Manos, M.M.; Bosch, F.X.; Kummer, J.A.; Shah, K.V.; Snijders, P.J.; Peto, J.; Meijer, C.J.; Muñoz, N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 1999, 189, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.L.; Cowart, C.J.; Rosen, B.L.; Pulczinski, J.C.; Solari, K.D.; Ory, M.G.; Smith, M.L. Characteristics associated with HPV diagnosis and perceived risk for cervical cancer among unmarried, sexually active college women. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.; Saleem, A.; Rai, N.; Shylasree, T.; Ashman, S.; Gregory, K.; Powell, N.; Tristram, A.; Fiander, A.; Hibbitts, S. Human Papillomavirus genotype testing combined with cytology as a ‘test of cure’post treatment: The importance of a persistent viral infection. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 52, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizon, S.; Murall, C.; Bravo, I. Why human papillomavirus acute infections matter. Viruses 2017, 9, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, K.F.; Waller, J.; Chorley, A.J.; Ferrer, R.A.; Haddrell, J.B.; Marlow, L.A. Barriers to cervical screening and interest in self-sampling among women who actively decline screening. J. Med. Screen. 2018, 25, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkensen, S.L.; Schiffman, M.; Sahasrabuddhe, V.; Flanigan, J.S. Is It Time to Move Beyond Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid for Cervical Cancer Screening? Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018, 6, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, T.A. Cervical cancer: Prevention and early detection. In Seminars in Oncology Nursing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 33, pp. 172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Castle, P.E.; de Sanjosé, S.; Qiao, Y.L.; Belinson, J.L.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; Kinney, W. Introduction of human papillomavirus DNA screening in the world: 15 years of experience. Vaccine 2012, 30, F117–F122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, M.; Kinney, W.K.; Cheung, L.C.; Gage, J.C.; Fetterman, B.; Poitras, N.E.; Lorey, T.S.; Wentzensen, N.; Befano, B.; Schussler, J.; et al. Relative performance of HPV and cytology components of cotesting in cervical screening. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 110, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, N.; Snijders, P.; Kenter, G.; Berkhof, J.; Meijer, C. HPV-based cervical screening: Rationale, expectations and future perspectives of the new Dutch screening programme. Prev. Med. 2018, 119, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref-Adib, M.; Freeman-Wang, T. Cervical cancer prevention and screening: The role of human papillomavirus testing. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 18, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, K.; Hall, S.; Nanda, K. Systematic evidence review number 25: Screening for cervical cancer. In Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stumbar, S.E.; Stevens, M.; Feld, Z. Cervical cancer and its precursors: A preventative approach to screening, diagnosis, and management. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2019, 46, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.A.; James, D.; Marzan, A.; Armaos, M. Cervical cancer: An overview of pathophysiology and management. In Seminars in Oncology Nursing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 35, pp. 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, P.; Meheus, F.; Chami, Y.; Hariprasad, R.; Zhao, F.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Management algorithms for cervical cancer screening and precancer treatment for resource-limited settings. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 138, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, M.G.; van Zummeren, M.; Rozendaal, L.; van Kemenade, F.J.; Helmerhorst, T.J.; Snijders, P.J.; Meijer, C.J.; Berkhof, J. Safety of extending screening intervals beyond five years in cervical screening programmes with testing for high risk human papillomavirus: 14 year follow-up of population based randomised cohort in the Netherlands. BMJ 2016, 355, i4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchener, H.C.; Gilham, C.; Sargent, A.; Bailey, A.; Albrow, R.; Roberts, C.; Desai, M.; Mather, J.; Turner, A.; Moss, S.; et al. A comparison of HPV DNA testing and liquid based cytology over three rounds of primary cervical screening: Extended follow up in the ARTISTIC trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzensen, N.; Schiffman, M.; Palmer, T.; Arbyn, M. Triage of HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. J. Clin. Virol. 2016, 76, S49–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benard, V.B.; Castle, P.E.; Jenison, S.A.; Hunt, W.C.; Kim, J.J.; Cuzick, J.; Lee, J.H.; Du, R.; Robertson, M.; Norville, S.; et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pileggi, C.; Flotta, D.; Bianco, A.; Nobile, C.G.; Pavia, M. Is HPV DNA testing specificity comparable to that of cytological testing in primary cervical cancer screening? Results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.A.; Andrews, K.S.; Brooks, D.; Fedewa, S.A.; Manassaram-Baptiste, D.; Saslow, D.; Wender, R.C. Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 184–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salina Zhang, B.; Batur, P.; Ncmp, C. Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2019, 86, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelband, H.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Gauvreau, C.L.; Horton, S.; Anderson, B.O.; Bray, F.; Cleary, J.; Dare, A.J.; Denny, L.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; et al. Costs, affordability, and feasibility of an essential package of cancer control interventions in low-income and middle-income countries: Key messages from Disease Control Priorities. Lancet 2016, 387, 2133–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.I.; Rositch, A.F.; Phelan-Emrick, D.F.; Gravitt, P.E. Uptake of HPV testing and extended cervical cancer screening intervals following cytology alone and Pap/HPV cotesting in women aged 30–65 years. Cancer Causes Control 2018, 29, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, B.F.; Erickson, B.K.; Huh, W.K. Cervical cancer screening: Evidence behind the guidelines. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayer, T.; Chen, Q. Personalized medicine. In Handbook of Healthcare Analytics: Theoretical Minimum for Conducting 21st Century Research on Healthcare Operations; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T.C.; Stoler, M.H.; Behrens, C.M.; Sharma, A.; Zhang, G.; Wright, T.L. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: End of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 136, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinney, W.; Fetterman, B.; Cox, J.T.; Lorey, T.; Flanagan, T.; Castle, P.E. Characteristics of 44 cervical cancers diagnosed following Pap-negative, high risk HPV-positive screening in routine clinical practice. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 121, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konecny, G.E. The path to personalized medicine in women’s cancers: Challenges and recent advances. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 27, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robertson, D.J.; Ladabaum, U. Opportunities and challenges in moving from current guidelines to personalized colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneş, E.D.; Örmeci, E.L. Or applications in disease screening. In Operations Research Applications in Health Care Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 297–325. [Google Scholar]

- Alagoz, O.; Hsu, H.; Schaefer, A.J.; Roberts, M.S. Markov decision processes: A tool for sequential decision making under uncertainty. Med. Decis. Mak. 2010, 30, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steimle, L.N.; Denton, B.T. Markov decision processes for screening and treatment of chronic diseases. In Markov Decision Processes in Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 189–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chhatwal, J.; Alagoz, O.; Burnside, E.S. Optimal breast biopsy decision-making based on mammographic features and demographic factors. Oper. Res. 2010, 58, 1577–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagoz, O.; Chhatwal, J.; Burnside, E.S. Optimal policies for reducing unnecessary follow-up mammography exams in breast cancer diagnosis. Decis. Anal. 2013, 10, 200–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnside, E.S.; Chhatwal, J.; Alagoz, O. What is the optimal threshold at which to recommend breast biopsy? PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48820. [Google Scholar]

- Yaylali, E.; Karamustafa, U. A Markov Decision Process Approach to Estimate the Risk of Obesity Related Cancers. In Industrial Engineering in the Big Data Era; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Ayvaci, M.U.; Alagoz, O.; Burnside, E.S. The effect of budgetary restrictions on breast cancer diagnostic decisions. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2012, 14, 600–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Önen, Z.; Sayin, S.; Gürvit, I.H. Optimal population screening policies for alzheimer’s disease. IISE Trans. Healthc. Syst. Eng. 2019, 9, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulionis, J.E.; Koutsiumaris, B. Partially observable Markov decision model for the treatment of early Prostate Cancer. Opsearch 2010, 47, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomer, A.; Nieboer, D.; Roobol, M.J.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Rizopoulos, D. Personalized schedules for surveillance of low-risk prostate cancer patients. Biometrics 2019, 75, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witteveen, A.; Otten, J.W.; Vliegen, I.M.; Siesling, S.; Timmer, J.B.; IJzerman, M.J. Risk-based breast cancer follow-up stratified by age. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 5291–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otten, J.W.M.; Witteveen, A.; Vliegen, I.; Siesling, S.; Timmer, J.B.; IJzerman, M.J. Stratified breast cancer follow-up using a partially observable MDP. In Markov Decision Processes in Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, K.; Scheller-Wolf, A.A.; Tayur, S.R. Personalized Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstr-act=3389539 (accessed on 16 May 2019).

- Ibrahim, R.; Kucukyazici, B.; Verter, V.; Gendreau, M.; Blostein, M. Designing personalized treatment: An application to anticoagulation therapy. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2016, 25, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayer, T.; Alagoz, O.; Stout, N.K.; Burnside, E.S. Designing a new breast cancer screening program considering adherence. In Proceedings of the INFORMS Annual Meeting, Austin, TX, USA, 7–11 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Dong, M.; Ren, Y.; Yin, K. How patient compliance impacts the recommendations for colorectal cancer screening. J. Comb. Optim. 2015, 30, 920–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayer, T.; Alagoz, O.; Stout, N.K. OR Forum—A POMDP approach to personalize mammography screening decisions. Oper. Res. 2012, 60, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan-Tabatabaei, R.; Sánchez, D.M.; Yeung, T.G. A Markov decision process model for cervical cancer screening policies in Colombia. Med. Decis. Mak. 2017, 37, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevik, M.; Ayer, T.; Alagoz, O.; Sprague, B.L. Analysis of mammography screening policies under resource constraints. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 949–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocken, M.; Helmerhorst, T.J.; Berkhof, J.; Louwers, J.A.; Nobbenhuis, M.A.; Bais, A.G.; Hogewoning, C.J.; Zaal, A.; Verheijen, R.H.; Snijders, P.J.; et al. Risk of recurrent high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia after successful treatment: A long-term multi-cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, M.; Timmer, J.; Witteveen, A. Stratified breast cancer follow-up using a continuous state partially observable Markov decision process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 281, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molani, S.; Madadi, M.; Wilkes, W. A partially observable Markov chain framework to estimate overdiagnosis risk in breast cancer screening: Incorporating uncertainty in patients adherence behaviors. Omega 2019, 89, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, M.; Nieminen, P.; Kotaniemi-Talonen, L.; Malila, N.; Tarkkanen, J.; Laurila, P.; Anttila, A. Age-specific evaluation of primary human papillomavirus screening vs conventional cytology in a randomized setting. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1612–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, F.A.; Beck, J.R. Markov models in medical decision making: A practical guide. Med. Decis. Mak. 1993, 13, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocken, M.; Uijterwaal, M.H.; de Vries, A.L.; Berkhof, J.; Ket, J.C.; Helmerhorst, T.J.; Meijer, C.J. High-risk human papillomavirus testing versus cytology in predicting post-treatment disease in women treated for high-grade cervical disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 125, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauskrecht, M. Value-function approximations for partially observable Markov decision processes. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2000, 13, 33–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, J.; Gordon, G.; Thrun, S. Point-based value iteration: An anytime algorithm for POMDPs. IJCAI Citeseer 2003, 3, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, V. Structural results for partially observed markov decision processes. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03873. [Google Scholar]

- Sondik, E.J. The Optimal Control of Partially Observable Markov Processes; Technical Report; Stanford University California Stanford Electronics Labs: Stanford, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood, R.D.; Sondik, E.J. The optimal control of partially observable Markov processes over a finite horizon. Oper. Res. 1973, 21, 1071–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walraven, E.; Spaan, M.T. Point-based value iteration for finite-horizon POMDPs. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2019, 65, 307–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, J.M.; Vlassis, N.; Spaan, M.T.; Poupart, P. Point-Based Value Iteration for Continuous POMDPs. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2006, 7, 2329–2367. [Google Scholar]

- Cassandra, A.R.; Kaelbling, L.P.; Littman, M.L. Acting optimally in partially observable stochastic domains. AAAI 1994, 94, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, G.E. State of the art—A survey of partially observable Markov decision processes: Theory, models, and algorithms. Manag. Sci. 1982, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.T. Algorithms for Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cassandra, A.R.; Littman, M.L.; Zhang, N.L. Incremental pruning: A simple, fast, exact method for partially observable Markov decision processes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1302.1525. [Google Scholar]

- Braziunas, D. POMDP Solution Methods; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- White, C.C. A survey of solution techniques for the partially observed Markov decision process. Ann. Oper. Res. 1991, 32, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, C.; Shani, G. The Skyline algorithm for POMDP value function pruning. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2012, 65, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walraven, E.; Spaan, M. Accelerated vector pruning for optimal POMDP solvers. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Eagle, J.N. The optimal search for a moving target when the search path is constrained. Oper. Res. 1984, 32, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, J.C.; Lacey, M.J.; Miller, J.D.; Lenhart, G.M.; Spitzer, M.; Kulkarni, R. The clinical and economic benefits of co-testing versus primary HPV testing for cervical cancer screening: A modeling analysis. J. Women’s Health 2016, 25, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, N.G.; Burger, E.A.; Sy, S.; Sharma, M.; Schiffman, M.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Hildesheim, A.; Herrero, R.; Kim, J.J. An updated natural history model of cervical cancer: Derivation of model parameters. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLay, L.A.; Foufoulides, C.; Merrick, J.R. Using simulation-optimization to construct screening strategies for cervical cancer. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2010, 13, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velanovich, V. Immediate biopsy versus observation for abnormal findings on mammograms: An analysis of potential outcomes and costs. Am. J. Surg. 1995, 170, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanmer, J.; Lawrence, W.F.; Anderson, J.P.; Kaplan, R.M.; Fryback, D.G. Report of nationally representative values for the noninstitutionalized US adult population for 7 health-related quality-of-life scores. Med. Decis. Mak. 2006, 26, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, E.; Xu, J. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_07-508.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2019).

| Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | 0.971 | 0.026 | 0.003 |

| 23 | 0.944 | 0.050 | 0.006 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| 41 | 0.714 | 0.251 | 0.035 |

| Risk Profile | Lifetime No. of Screenings | Avg. Screening Interval Length | Lifetime Avg. Risk of Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| ine Low risk | 7 | 6.86 | 0.0849 |

| Medium risk | 9 | 5.33 | 0.125 |

| High risk | 12 | 4 | 0.209 |

| Start Age | Screen Interval Length | Screen Rounds | Stop Age | Exp. False Results | Exp. QALY Gain | Improve In QALY(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No screening | - | - | 0 | - | 0 | 56.346 | - |

| Modified US practice | 21 | 5 | 10 | 66 | 0.18 | 56.119 | 0 |

| Aggressive plan | 21 | 3 | 16 | 59 | 0.252 | 57.156 | 1.4 |

| Alternative policy 1 | 21 | 6 | 9 | 69 | 0.162 | 57.075 | 1.3 |

| Alternative policy 2 | 40 | 5 | 6 | 66 | 0.108 | 57.004 | 1.18 |

| Alternative policy 3 | 50 | 5 | 4 | 66 | 0.072 | 56.824 | 0.87 |

| POMDP policy | 23 | variable | 9 | 67 | 0.162 | 57.228 | 1.57 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ebadi, M.; Akhavan-Tabatabaei, R. Personalized Cotesting Policies for Cervical Cancer Screening: A POMDP Approach. Mathematics 2021, 9, 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9060679

Ebadi M, Akhavan-Tabatabaei R. Personalized Cotesting Policies for Cervical Cancer Screening: A POMDP Approach. Mathematics. 2021; 9(6):679. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9060679

Chicago/Turabian StyleEbadi, Malek, and Raha Akhavan-Tabatabaei. 2021. "Personalized Cotesting Policies for Cervical Cancer Screening: A POMDP Approach" Mathematics 9, no. 6: 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9060679

APA StyleEbadi, M., & Akhavan-Tabatabaei, R. (2021). Personalized Cotesting Policies for Cervical Cancer Screening: A POMDP Approach. Mathematics, 9(6), 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9060679