Satisfaction of Tuberculosis Patients with Directly Observed Treatment Strategy under Pakistan Health Care Policy: A Mixed-Method Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

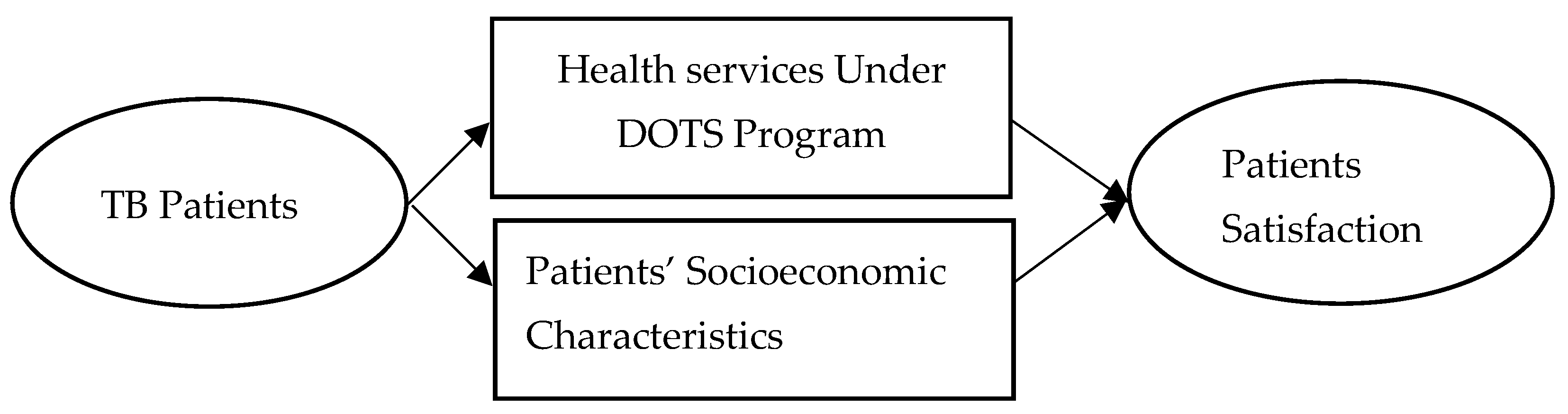

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Study Design

3.3. Sampling

3.4. Inclusion Criteria

3.5. Exclusion Criteria

3.6. Data Collection

3.7. Validation, Reliability, and Credibility

3.8. Data Analysis

3.8.1. Statistical Tests

3.8.2. Regression Analysis

3.8.3. Dependent Variable

3.8.4. Independent Variables

3.9. Operational Definitions of Satisfaction

4. Results

4.1. Results of Quantitative Data Analysis

4.1.1. Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

4.1.2. Satisfaction Level of Respondents

| Measuring Items | Very Low n (%) | Low n (%) | Moderate n (%) | High n (%) | Very High n (%) | Mean | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Satisfaction 1 Item | 53 (19.70) | 90 (33.46) | 73 (27.14) | 40 (14.84) | 13 (4.83) | 2.51 | 1.11 | 0.942 |

| Satisfaction in Structure of DOTS | ||||||||

| Space for Patients | 56 (20.82) | 108 (40.15) | 54 (20.07) | 41 (15.24) | 10 (3.72) | 2.41 | 0.07 | 0.940 |

| Availability of Safe Drinking Water | 109 (40.52) | 75 (27.88) | 50 (18.59) | 28 (10.41) | 7 (2.60) | 2.07 | 0.07 | 0.943 |

| Availability of Toilets | 46 (17.10) | 79 (29.37) | 71 (26.39) | 60 (22.30) | 13 (4.83) | 2.68 | 0.07 | 0.941 |

| Treatment Process | 40 (14.87) | 90 (33.46) | 73 (27.14) | 51 (18.96) | 15 (5.58) | 2.67 | 0.07 | 0.940 |

| Access to Medicine | 20 (7.43) | 22 (8.18) | 42 (15.61) | 152 (56.51) | 33 (12.27) | 3.58 | 0.06 | 0.940 |

| Privacy at TB Centre | 48 (17.84) | 108 (40.15) | 89 (33.09) | 13 (4.83) | 11 (4.09) | 2.37 | 0.06 | 0.941 |

| Laboratory Services | 22 (8.18) | 20 (7.43) | 68 (25.28) | 119 (44.24) | 40 (14.87) | 3.50 | 0.07 | 0.941 |

| Availability of Medicines | 20 (7.43) | 22 (8.18) | 42 (15.61) | 152 (56.51) | 33 (12.27) | 3.58 | 0.06 | 0.940 |

| Availability of Doctors | 34 (12.64) | 100 (37.17) | 58 (21.56) | 66 (24.54) | 11 (4.09) | 2.70 | 0.07 | 0.940 |

| Availability of Equipment | 43 (15.99) | 102 (37.92) | 74 (27.51) | 40 (14.87) | 10 (3.72) | 2.52 | 0.06 | 0.942 |

| Availability of Signage/Directions | 32 (11.90) | 100 (37.17) | 70 (26.02) | 55 (20.45) | 12 (4.46) | 2.68 | 0.06 | 0.941 |

| DOTS Processes | ||||||||

| Convenience of Service Hours | 37 (13.75) | 88 (32.71) | 57 (21.19) | 74 (27.51) | 13 (4.83) | 2.77 | 0.07 | 0.942 |

| Waiting Time | 90 (33.46) | 93 (34.57) | 47 (17.47) | 28 (10.41) | 11 (4.09) | 2.17 | 0.07 | 0.941 |

| Appointment Process | 30 (11.15) | 98 (36.43) | 105 (39.03) | 27 (10.04) | 9 (3.35) | 2.58 | 0.06 | 0.941 |

| Attitude of Health Personnel | 19 (7.06) | 65 (24.16) | 100 (37.17) | 72 (26.77) | 13 (4.83) | 2.98 | 0.06 | 0.941 |

| Care of Health Personnel | 21 (7.81) | 42 (15.61) | 136 (50.56) | 55 (20.45) | 15 (5.58) | 3.00 | 0.06 | 0.940 |

| Guidance on Sickness | 25 (9.29) | 76 (28.25) | 63 (23.42) | 88 (32.71) | 17 (6.32) | 2.99 | 0.07 | 0.939 |

| Consultation | 57 (21.19) | 52 (19.33) | 69 (25.65) | 78 (29.00) | 13 (4.83) | 2.77 | 0.07 | 0.940 |

| Skill of Health Professionals | 28 (10.41) | 29 (10.78) | 72 (26.77) | 128 (47.58) | 12 (4.46) | 3.25 | 0.06 | 0.940 |

| Cost of Medicine | 30 (11.15) | 90 (33.46) | 72 (26.77) | 56 (20.82) | 21 (7.81) | 2.81 | 0.07 | 0.943 |

| Cost of Transportation | 37 (13.75) | 82 (30.48) | 61 (22.68) | 66 (24.54) | 23 (8.55) | 2.84 | 0.07 | 0.942 |

| Equality between Rich and Poor | 24 (8.92) | 25 (9.29) | 93 (34.57) | 108 (40.15) | 19 (7.06) | 3.27 | 0.06 | 0.940 |

| Outcome of DOTS | ||||||||

| Symptoms Reduction | 18 (6.69) | 19 (7.06) | 53 (19.70) | 155 (57.62) | 24 (8.92) | 3.55 | 0.06 | 0.940 |

| Overall effect of Medicine | 26 (9.67) | 22 (8.18) | 70 (26.02) | 130 (48.33) | 21 (7.81) | 3.36 | 0.06 | 0.940 |

| Psychological Effect | 44 (16.36) | 44 (16.36) | 70 (26.02) | 95 (35.32) | 16 (5.95) | 2.98 | 0.07 | 0.940 |

| Feeling Energetic | 87 (32.34) | 62 (23.05) | 63 (23.42) | 44 (16.36) | 13 (4.83) | 2.38 | 0.07 | 0.941 |

| Total (26 Items) | 2.86 | 0.69 | 0.943 | |||||

4.1.3. Comparison of Patients

4.1.4. Regression Results

4.2. Results of Qualitative Data Analysis

4.2.1. General Conditions of the Health Facilities

“Safe drinking water is not available. We do not even have drinking water. I have been coming to this TB center since the last four months, but still no water is available at the center.”(Patient-A-11, age 34, female)

“I didn’t see any water coolers in the TB center. I brought water with me from home every time. However, I have seen people drink from the tap at the center.”(Patient-E-3, age 25, male)

“We are in a temporary building, here, no water is available for drinking, and no wash rooms. Whenever there is need of water, we manage it from an outside building.”(KI-Medical Officer)

“There is no place for sitting at the center. Some space is available, but it is allocated to females. Usually, we stand for the whole day, waiting for doctor’s appointment. No chairs are there, at the center, too.”(Patient-A-44, age 45, male)

“We have not enough space for patients in the TB center. Females are setting in front of the laboratory where everyone has to pass through them.”(KI-laboratory technician)

“Whenever, I come to TB center, the doctors check many patients in the room. There is no privacy at all; even sometimes my own village people came to know that here I have TB.”(Patient-G-2, age 21, female)

“Many problems I cannot discuss in front of the doctor, as many patients are always sitting around.”(Patient-H-1, age 28, female)

4.2.2. DOTS Process

“We have no problem in the process of appointment and the health workers have very good behavior with patients.”(Patient A-34, age, 29, female)

4.2.3. Outcome of DOTS

“I have regained no energy, since I started these medicines, but of course it has reduced my cough.”(Patient-A-23, age 45, female)

“It is very difficult to take these medicines. I feel very weak, have no energy and no mood to work and walk.”(Patient-C-139, age. 55, male)

4.2.4. Other Issues

“I cannot come alone to the TB center. If my husband is free, he will come with me or I will call my brother to take me to the health center.”(Patient-A-131, age 24, female)

“Sometime, I feel pain, but have to wait for the male family member. When they are free, then we will go to see the doctor. I am not allowed to go out from home without being accompanied by someone from the family.”(Patient-F-3, age 27, female)

4.2.5. Low Income and Poverty

“I am a student, and my father is a wage laborer, who supports a family of ten. Every day, I get an amount from my father to go to college. Besides this, he has to pay me when I go to see the doctor, every month or two times in a month. The cost of the medicine and the traveling cost are very high. Usually, I don’t buy some of the medicine due lack of money.”(Patient-C-9, age 20, male)

“We are from the northern part, and every year we come here in winter and go back in the summer. We do not know someone to help us to approach a doctor. We are not treated the same way as the people from the district are.”(Patient-H-2, age 45, male)

5. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Overall Satisfaction 1 Item |

| Satisfaction in Structure of DOTS |

| Space for Patients |

| Availability of Safe Drinking Water |

| Availability of Toilets |

| Treatment Process |

| Access to Medicine |

| Privacy at TB Centre |

| Laboratory Services |

| Availability of Medicines |

| Availability of Doctors |

| Availability of Equipment |

| Availability of Signage / Directions |

| DOTS Processes |

| Convenience of Service Hours |

| Waiting Time |

| Appointment Process |

| Attitude of Health Personnel |

| Care of Health Personnel |

| Guidance on Sickness |

| Consultation |

| Skill of Health Professionals |

| Cost of Medicine |

| Cost of Transportation |

| Equality between Rich and Poor |

| Outcome of DOTS |

| Symptoms Reduction |

| Overall effect of Medicine |

| Psychological Effect |

| Feeling Energetic |

References

- Ullah, W.; Wali, A.; Haq, M.U.; Yaqoob, A.; Fatima, R.; Khan, G.M. Public—Private Mix Models of Tuberculosis Care in Pakistan: A High-Burden Country Perspective. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 703631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. End TB Strategy; WHO: Genewa, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Stop TB Strategy; WHO: Genewa, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, M.H.; Shahzad, F.; Khan, M.A.; Qadeer, E.; Mørkve, O. Loss to Follow-up Pattern in TB Patients in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. J. Med. 2015, 16, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. An Expanded DOTS Framework for Effective Tuberculosis Control; WHO: Genewa, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Onozaki, I.; Raviglione, M. Stopping tuberculosis in the 21st century: Goals and strategies. Respirology 2010, 15, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, C.; Glaziou, P.; Floyd, K.; Raviglione, M. Prospects for Tuberculosis Elimination. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Rozi, S.; White, F.; Hasan, R. Cohort analysis of directly observed treatment outcomes for tuberculosis patients in urban Pakistan. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.S.; Suwannapong, N.; Howteerakul, N.; Pacheun, O.; Rajatanun, T. Improvement of district hospital service system to increase treatment adherence among tuberculosis patients in Pakistan. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2011, 42, 664. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, A.; Yahya, M.; Kumar, R. An Audit of Tuberculosis from a Private Hospital in Karachi. Pak. J. Chest Med. 2015, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.; Cataldo, J. A systematic review of global cultural variations in knowledge, attitudes and health responses to tuberculosis stigma. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2014, 18, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saqib, S.E.; Ahmad, M.M.; Amezcua-Prieto, C. Economic burden of tuberculosis and its coping mechanism at the household level in pakistan. Soc. Sci. J. 2018, 55, 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Buregyeya, E.; Criel, B.; Nuwaha, F.; Colebunders, R. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in Wakiso and Mukono districts, Uganda. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datiko, D.G.; Jerene, D.; Suarez, P. Patient and health system delay among TB patients in Ethiopia: Nationwide mixed method cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Sobrinho, R.A.; Andrade, R.L.d.P.; Ponce, M.A.Z.; Wysocki, A.D.; Brunello, M.E.; Scatena, L.M.; Ruffino-Netto, A.; Villa, T.C.S. Delays in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in a town at the triple border of Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2012, 31, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saqib, S.E.; Ahmad, M.M.; Amezcua-Prieto, C.; Virginia, M.R. Treatment delay among pulmonary tuberculosis patients within the pakistan national tuberculosis control program. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 99, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. Pakistan—Harnessing the Government Lady Health Worker Programme to Increase Community-Based Active TB Case-Finding; World Health Organization: Genewa, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, F.; Panezai, S.; Saqib, S.E.; Fatima, K. Assessing the Quality, Use and Determinant of Family Planning Services: The Case of Panjgur District, Balochistan. Public Health Res. 2021, 11, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Saqib, S.E.; Ahmad, M.M.; Panezai, S. Care and social support from family and community in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in pakistan. Fam. Med. Community Health 2019, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hino, P.; Takahashi, R.F.; Bertolozzi, M.R.; Egry, E.Y. The health needs and vulnerabilities of tuberculosis patients according to the accessibility, attachment and adherence dimensions. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2011, 45, 1656–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paz, E.P.A.; Sá, A.M.M. The daily routine of patients in tuberculosis treatment in basic health care units: A phenomenological approach. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2009, 17, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ozawa, S.; Pongpirul, K. 10 best resources on… mixed methods research in health systems. Health Policy Plan. 2013, 29, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naseem, S.; Panezai, S.; Saqib, S.E. Identifying coverage bottlenecks in the maternal, neonatal and child health care services in panjgur district, pakistan. J. Geog. Soc Sci. 2020, 2, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, E.; Ounsa, M.; Al Mansour, M.; Alzahrani, M.; Abdalla, S.; Medani, K.; Sidahmed, H.; Sami, W. Patients’ satisfaction with tuberculosis services of directly observed therapy programs in the gezira state of sudan. Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen, D.E.; Rootman, I. Physician role performance and patient satisfaction. Soc. Sci. Med. 1976, 10, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R. Development of a questionnaire to assess patients’ satisfaction with consultations in general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 1990, 40, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van der Eijk, M.; Nijhuis, F.A.; Faber, M.J.; Bloem, B.R. Moving from physician-centered care towards patient-centered care for Parkinson’s disease patients. Park. Relat. Disord. 2013, 19, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeonoro, U.U.; Chukwu, J.N.; Nwafor, C.C.; Meka, A.O.; Omotowo, B.I.; Madichie, N.O.; Ogbudebe, C.; Ikebudu, J.N.; Oshi, D.C.; Ekeke, N. Evaluation of Patient Satisfaction with Tuberculosis Services in Southern Nigeria. Health Serv. Insights 2015, 8, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.M.; González, N.; Bilbao, A.; Aizpuru, F.; Escobar, A.; Esteban, C.; San-Sebastián, J.A.; de-la-Sierra, E.; Thompson, A. Predictors of patient satisfaction with hospital health care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chimbindi, N.; Bärnighausen, T.; Newell, M.-L. Patient satisfaction with HIV and TB treatment in a public programme in rural KwaZulu-Natal: Evidence from patient-exit interviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palha, P.F.; Silva, L.M.C.d.; Wysocki, A.D.; Andrade, R.L.d.P.; Protti, S.T.; Scatena, L.M.; Villa, T.C.S. Access to healthcare services for tuberculosis: Analysis of patient satisfaction. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2012, 46, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- District TB Office. TB Health Facilities; District TB Office Mardan: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Klassen, A.C.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Smith, K.C. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences; WHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DHIS. Disease Pattern in Out Patient Department; District Health Information System, K.P.K. Dept. Of Health: Peshawar, Pakistan, 2014.

- Distric TB Office. Consolidated Report: Consolidated Report of TB Reporting Centers; DTO: Mardan, Pakistan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Naing, L.; Winn, T.; Rusli, B. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch. Orofac. Sci. 2006, 1, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lwanga, S.K.; Lemeshow, S. Sample Size Determination in Health Studies: A Practical Manual; WHO: Genewa, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sunnetcioglu, A.; Sunnetcioglu, M.; Binici, I.; Baran, A.I.; Karahocagil, M.K.; Saydan, M.R. Comparative analysis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis of 411 cases. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2015, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srivastav, S.; Mahajan, H. Satisfaction levels among patients availing DOTS services in Bundelkhand Region (UP), India: Evidence from patient exit-interviews. Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health 2014, 7, 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Getahun, B.; Nkosi, Z.Z. Satisfaction of patients with directly observed treatment strategy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nezenega, Z.S.; Tafere, T.E. Patient satisfaction on tuberculosis treatment service and adherence to treatment in public health facilities of Sidama zone, South Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Portela, M.C.; Lima, S.M.L.; Brito, C.; Ferreira, V.M.B.; Escosteguy, C.C.; Vasconcellos, M.T.L.D. Tuberculosis Control Program and patient satisfaction, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 2014, 48, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rai, N.; Singh, S.; Kushwah, S.; Dubey, D. A cross sectional study on evaluation of satisfaction level of TB patients enrolled for directly observed treatment, short course chemotherapy in a district of Central India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2016, 4, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Abri, R.; Al-Balushi, A. Patient satisfaction survey as a tool towards quality improvement. Oman Med. J. 2014, 29, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, R.M.; Abdullah, M.S.; Rahman, A.M.; Alam, A.M. Identifying role of perceived quality and satisfaction on the utilization status of the community clinic services; Bangladesh context. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dansereau, E.; Masiye, F.; Gakidou, E.; Masters, S.H.; Burstein, R.; Kumar, S. Patient satisfaction and perceived quality of care: Evidence from a cross-sectional national exit survey of HIV and non-HIV service users in Zambia. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenager, G.S.; Alemseged, F.; Asefa, H.; Gebremedhin, A.T. Factors Associated with Treatment Delay among Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients in Public and Private Health Facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2017, 2017, 5120841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M. Initiation and adherence to TB treatment in a Pakistani community influenced more by perceptions than by knowledge of tuberculosis. J. Assoc. Chest Physicians 2013, 1, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.A.; Fonseca, F.O.; Moraes, A.H.A.N.; Martins, A.; Oliveira, N.; Lima, L.; Dias, G.; Saad, M.H.F. Environmental aspects related to tuberculosis and intestinal parasites in a low-income community of the Brazilian Amazon. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2017, 59, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panezai, S.; Ahmed, M.M.; Saqib, S.E. Gender differences in client satisfaction and its relationship with utilization of primary health care services in Pakistan. J. Geogr. Soc. Sci. 2019, 1, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nwabueze, S.; Adogu, P.; Ilika, A.; Asuzu, M. Comparative analysis of patient satisfaction levels in HIV/AIDS care in secondary and tertiary health care facilities in Nigeria. Afrimedic J. 2010, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Panezai, S.; Ahmad, M.M.; e Saqib, S. Exploring the Reasons for Underutilization of Primary Health Care Services in Pakistan: A Qualitative Analysis. Ponte J. 2020, 76, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. Evaluation of patient satisfaction level undergoing Dots therapy in meerut district of uttar pradesh. J. Adv. Med. Dent. Sci. Res. 2015, 3, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder, T.; Klewer, J.; Kugler, J. Determinants of patient satisfaction: A study among 39 hospitals in an in-patient setting in Germany. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2011, 23, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Increasing Access to Health Workers in Remote and Rural Areas through Improved Retentio; WHO: Genewa, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, S.B.; Ejaz, E.I.; Achakzai, A.D.; Shafiq, S.Y. Political and economic unfairness in health system of Pakistan: A hope with the recent reforms. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2013, 25, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panezai, S.; Ahmad, M.M.; Saqib, S.E. Factors affecting access to primary health care services in Pakistan: A gender-based analysis. Dev. Pract. 2017, 27, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, A.; Panezai, S. Assessing the quality of primary health care services at basic health units in quetta city, balochistan, pakistan. Public Health Res. 2021, 11, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Bhatti, M.A.; Kuroiwa, C. Challenges in access to and utilization of reproductive health care in Pakistan. J. Ayub Med. Coll Abbottabad 2008, 20, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmqvist, M.; Bara, A.-C. Patient characteristics and quality dimensions related to patient satisfaction. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2010, 22, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charokar, K.; Jain, A.K. Evaluation of Patient Satisfaction in Relation to Patient Factors in Surgical Centre—A Study from Central India. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2015, 1, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Satisfaction | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissatisfied | Satisfied | Chi-Square Test Value | p-Value | ||

| Gender (X1) | |||||

| Female | 61 (43.88) | 78 (56.12) | 7.639 | 0.010 ** | |

| Male | 36 (27.69) | 94 (72.31) | |||

| Marital status (X2) | |||||

| Unmarried | 48 (52.75) | 43 (47.25) | 16.716 | 0.000 ** | |

| Married | 44 (27.16) | 118 (72.84) | |||

| Deceased wife | 5 (31.25) | 11 (68.75) | |||

| Location (X3) | |||||

| Rural | 26 (25.74) | 75 (74.26) | 7.466 | 0.010 ** | |

| Urban | 71 (42.26) | 97 (57.74) | |||

| Employment status (X4) | |||||

| No | 82 (48.81) | 86 (51.19) | 31.548 | 0.000 ** | |

| Yes | 15 (14.85) | 86 (85.15) | |||

| House ownership (X5) | |||||

| No | 72 (47.68) | 79 (52.32) | 20.168 | 0.000 ** | |

| Yes | 25 (21.19) | 93 (78.81) | |||

| Literacy (X6) | |||||

| Illiterate | 62(42.47) | 84(57.53) | 5.683 | 0.020 * | |

| Literate | 35 (28.46) | 88 (71.54) | |||

| Main households’ occupation (X7) | |||||

| Agriculture | 35 (45.45) | 42 (54.55) | 14.30 † | 0.000 ** | |

| Trade | 19 (46.34) | 22 (53.66) | |||

| Labor | 31(33.70) | 61 (66.30) | |||

| Servant | 4 (12.12) | 29 (87.88) | |||

| Others | 8 (30.77) | 18 (69.23) | |||

| Households’ level of Income (X8) | |||||

| <250 USD | 68 (46.26) | 79 (53.74) | 14.44 † | 0.000 ** | |

| 250–500 | 20 (24.10) | 63 (75.90) | |||

| 501–750 | 5 (21.74) | 18 (78.26) | |||

| >750 | 4 (25.00) | 12 (75.00) | |||

| Age categories (X9) | |||||

| 15–20 Years | 29 (46.03) | 34 (53.97) | 7.65 † | 0.1 | |

| 21–30 | 29 (32.95) | 59 (67.05) | |||

| 31–40 | 17 (31.48) | 37 (68.52) | |||

| 41–50 | 19 (42.22) | 26 (57.78) | |||

| 51–60 | 3 (15.79) | 16 (84.21) | |||

| COR (95% CI) | p-Value | AOR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (X1) | ||||

| Female | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Male | 2.04 (1.23–3.40) | 0.006 ** | 2.21 (1.07–4.58) | 0.033 * |

| Marital status (X2) | ||||

| Unmarried | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Married | 2.57 (1.51–4.36) | 0.000 ** | 3.126 (1.45–6.73) | 0.004 ** |

| Deceased wife | 2.20 (0.71–6.81) | 0.172 | 2.524 (0.47–13.68) | 0.283 |

| Location (X3) | ||||

| Rural | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Urban | 2.11 (1.23–3.63) | 0.007 ** | 1.89 (0.93–3.69) | 0.078 * |

| Employment status (X4) | ||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 5.45 (2.92–10.23) | 0.000 ** | 5.22 (2.44–1.21) | 0.000 ** |

| House ownership (X5) | ||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 3.39 (1.97–5.85) | 0.000 ** | 3.82 (1.94–7.54) | 0.000 ** |

| Literacy (X6) | ||||

| Illiterate | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Literate | 1.86 (1.11–3.09) | 0.018 * | 2.17 (1.11–4.25) | 0.023 * |

| Main households’ occupation (X7) | ||||

| Agriculture | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Trade | 0.97 (0.45–2.06) | 0.927 | 0.59 (0.22–1.59) | 0.300 |

| Labor | 1.64 (0.88–3.06) | 0.120 | 1.22 (0.56–2.65) | 0.618 |

| Servant | 6.04 (1.94–18.85) | 0.002 ** | 4.42 (1.12–17.38) | 0.033 * |

| Others | 1.86 (0.73–4.83) | 0.193 | 0.63 (0.18–2.16) | 0.459 |

| Households’ level of Income (X8) | ||||

| <250 USD | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 250–500 | 2.71(1.49–4.93) | 0.001 ** | 2.39 (1.13–5.04) | 0.023 * |

| 501–750 | 3.10 (1.09–8.79) | 0.033 * | 1.67 (0.42–6.63) | 0.463 |

| >750 | 2.58 (0.79–8.38) | 0.114 | 1.33 (0.33–5.35) | 0.693 |

| Age categories (X9) | ||||

| 15–20 Years | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 21–30 | 1.79 (0.93–3.48) | 0.083 | 0.96 (0.41–2.24) | 0.924 |

| 31–40 | 1.81 (0.859–3.83) | 0.118 | 0.79 (0.27–2.35) | 0.678 |

| 41–50 | 1.12 (0.51–2.42) | 0.784 | 0.66 (0.22–1.92) | 0.445 |

| 51–60 | 15.88 (1.99–126.20) | 0.009 ** | 7.39 (0.73–74.88) | 0.090 |

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test | Chi-Square Value = 11.017, df = 8 and p = 0.201 | |||

| Categories | Sub-Categories |

|---|---|

| General conditions of health facilities | Infrastructure facilities |

| Availability of health services and facilities | |

| DOTS process | Convenience |

| Process of appointment | |

| Attitude of the health personnel | |

| DOTS outcome | Improvement in health status |

| Psychological effects | |

| Other issues | Gender related |

| Rural and urban | |

| Low income and poverty |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaiya, C.; Panezai, S.; Saqib, S.E.; Ashraf, M. Satisfaction of Tuberculosis Patients with Directly Observed Treatment Strategy under Pakistan Health Care Policy: A Mixed-Method Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122529

Chaiya C, Panezai S, Saqib SE, Ashraf M. Satisfaction of Tuberculosis Patients with Directly Observed Treatment Strategy under Pakistan Health Care Policy: A Mixed-Method Study. Healthcare. 2022; 10(12):2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122529

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaiya, Chitralada, Sanaullah Panezai, Shahab E. Saqib, and Muhammad Ashraf. 2022. "Satisfaction of Tuberculosis Patients with Directly Observed Treatment Strategy under Pakistan Health Care Policy: A Mixed-Method Study" Healthcare 10, no. 12: 2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122529

APA StyleChaiya, C., Panezai, S., Saqib, S. E., & Ashraf, M. (2022). Satisfaction of Tuberculosis Patients with Directly Observed Treatment Strategy under Pakistan Health Care Policy: A Mixed-Method Study. Healthcare, 10(12), 2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122529