Changes and Determinants of Maternal Health Services Utilization in Ethnic Minority Rural Areas in Central China, 1991–2015: An Ecological Systems Theory Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings

2.2. Study Design and Sample

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

2.3.2. Independent Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

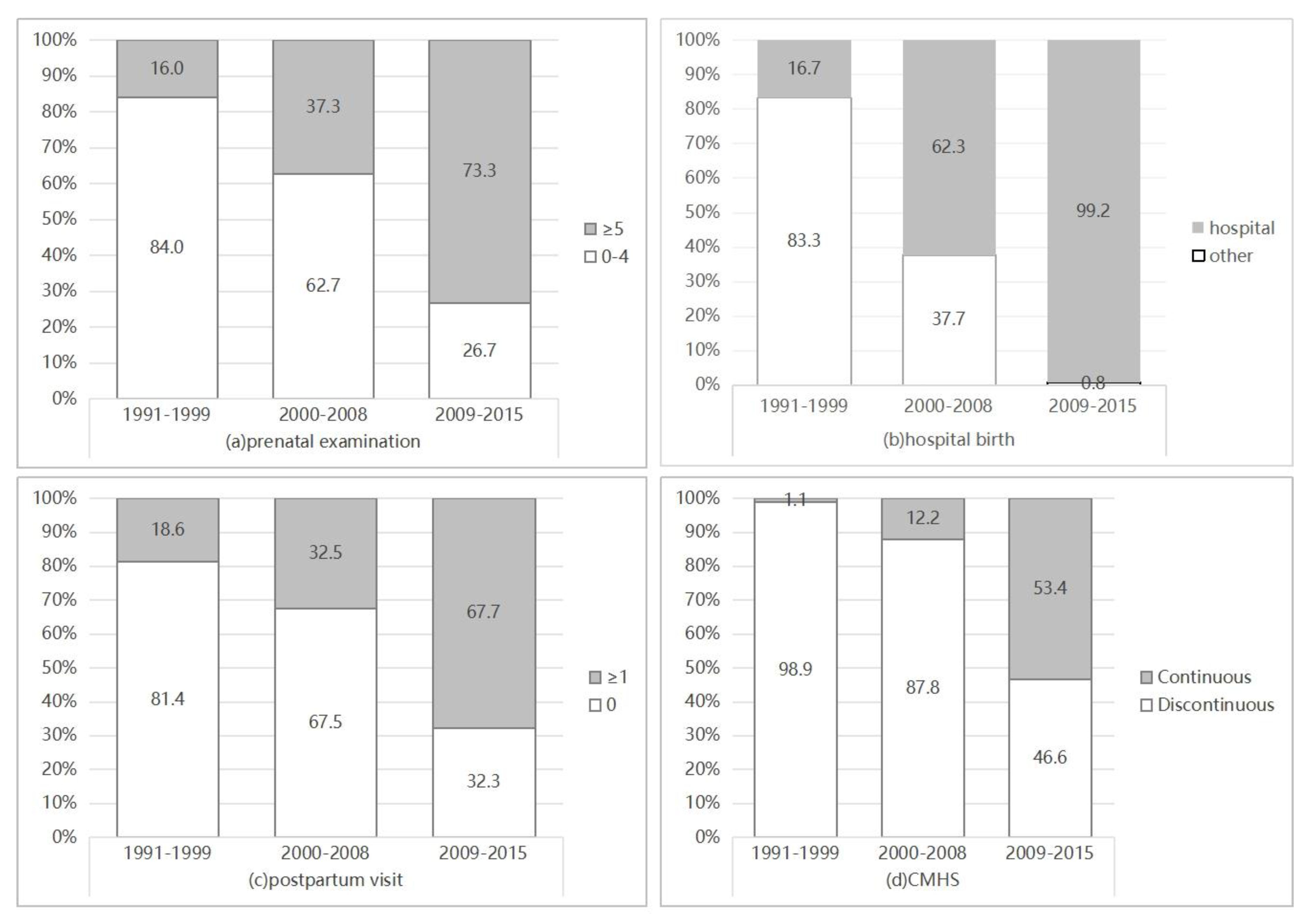

3.2. Changes in Maternal Services Utilization in Enshi, 1991–2015

3.3. Determinants of Maternal Healthcare Utilization

3.3.1. Factors Associated with Prenatal Examinations

3.3.2. Factors Associated with Hospital Births

3.3.3. Factors Associated with Postpartum Visits

3.3.4. Factors Associated with the Continuum of Maternal Health Service

4. Discussion

4.1. Toward Universal Maternal Health Coverage: Progress and Gap

4.2. The Determinants of Maternal Healthcare Utilization

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheets: Maternal Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Minh, H.V.; Giang, K.B.; Hoat, L.N.; Chung, L.H.; Huong, T.T.G.; Phuong, N.T.K.; Valentine, N.B. Analysis of selected social determinants of health and their relationships with maternal health service coverage and child mortality in Vietnam. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 28836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Sustainable Development. United Nations. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals-Health Targets. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/ (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheets: Maternal Mortality. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Liang, J.; Li, X.; Kang, C.; Wang, Y.; Kulikoff, X.R.; Coates, M.M.; Ng, M.; Luo, S.; Mu, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Maternal mortality ratios in 2852 Chinese counties, 1996–2015, and achievement of Millennium Development Goal 5 in China: A subnational analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2019, 393, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsmans, C.; Graham, W.J. Maternal survival 1—Maternal mortality: Who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006, 368, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Han, X.; You, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y. Maternal health services utilization and maternal mortality in China: A longitudinal study from 2009 to 2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, J.R.; Stoll, B.J.; Lucas, A.O. Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oyerinde, K. Can Antenatal Care Result in Significant Maternal Mortality Reduction in Developing Countries? J. Community Med. Health Educ. 2013, 3, e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunze, K.; Higgins-Steele, A.; Simen-Kapeu, A.; Vesel, L.; Kim, J.; Dickson, K. Innovative approaches for improving maternal and newborn health—A landscape analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Global Database on Maternal Health Indicators. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/maternal_health/en/ (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Song, Y.; Ma, J.; Fu, W.; Pang, R.; et al. A Lancet Commission on 70 years of women’s reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health in China. Lancet 2021, 397, 2497–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qian, X.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Escobar, E.; Story, M.; Tang, S. Towards universal access to skilled birth attendance: The process of transforming the role of traditional birth attendants in Rural China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L. The work evolvement of “Reducing and Eliminating Items”. Mater Child Health Care China 2001, 6, 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance. Further Strengthening the Hospital Delivery for Rural Women; National Health and Family Planning Commission of PRC: Beijing, China, 2009. Available online: http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/mohbgt/s9507/200902/38943.shtml (accessed on 13 May 2016). (In Chinese)

- Zhao, P.; Han, X.; You, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y. Effect of basic public health service project on neonatal health services and neonatal mortality in China: A longitudinal time-series study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e34427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhan, Y.; Berhan, A. Antenatal care as a means of increasing birth in the health facility and reducing maternal mortality: A systematic review. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2014, 24, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelke, B.; Werner, E. The Fourth Trimester of Pregnancy: Committing to Maternal Health and Well-Being Postpartum. R. I. Med. J. 2018, 101, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of PRC. National Essential Public Health Services Standards; National Health and Family Planning Commission of PRC: Beijing, China, 2009. Available online: http://www.moh.gov.cn/jws/s3581r/200910/fe1cdd87dcfa4622abca696c712d77e8.shtml (accessed on 17 March 2016). (In Chinese)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (People’s Republic of China), UN System in China. Report on China’s implementation of the Millennium Development Goals (2000–2015); United Nations Development Programme: Beijing, China, 2015; Available online: https://www.unicef.cn/sites/unicef.org.china/files/2018-08/mdg-report-china-2015.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. China Statistical Yearbook on Health 2019; China Union Medical College Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Working Committee on Children and Women under State Council of PRC. The China Maternal and Child Health Development Report (2019). Available online: https://www.nwccw.gov.cn/2019-05/28/content_256162.htm (accessed on 12 January 2022). (In Chinese)

- Song, P.; Kang, C.; Theodoratou, E.; Rowa-Dewar, N.; Liu, X.; An, L. Barriers to Hospital Deliveries among Ethnic Minority Women with Religious Beliefs in China: A Descriptive Study Using Interviews and Survey Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.L.; Guo, S.; Hipgrave, D.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Song, L.; Yang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Ronsmans, C. China’s facility-based birth strategy and neonatal mortality: A population-based epidemiological study. Lancet 2011, 378, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, L.; Deng, S.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Su, H.; Lv, J. Analysis of Relevant Factors of Maternal Mortality in Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture from 1999 to 2014. Chin. J. Med. Soc. 2017, 30, 31–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chaka, E.E.; Parsaeian, M.; Majdzadeh, R. Factors Associated with the Completion of the Continuum of Care for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Services in Ethiopia. Multilevel Model Analysis. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q.; Roque, M.; Nuzhath, T.; Hossain, M.M.; Jin, X.; Aggad, R.; Myint, W.W.; Zhang, G.; McKyer, E.L.J.; Ma, P. Changes in Levels and Determinants of Maternal Health Service Utilization in Ethiopia: Comparative Analysis of Two Rounds Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Ding, L.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C. Antenatal care use and its determinants among migrant women during the first delivery: A nation-wide cross-sectional study in China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, Z.; Dang, S.; Xu, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Su, M.; Wang, D.; Chen, G. Exploring status and determinants of prenatal and postnatal visits in western China: In the background of the new health system reform. BMC Public Health 2017, 18, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Kumar, M.; Zhou, Z.; Lee, C.; Wang, D.; Liu, H.; Dang, S.; Gao, J. Influence of China’s 2009 healthcare reform on the utilisation of continuum of care for maternal health services: Evidence from two cross-sectional household surveys in Shaanxi Province. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Q.; Cao, M.; Medina, A.; Rozelle, S. Use of maternal health services among women in the ethnic rural areas of western China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Xiao, D.; Ren, H. Implications from the social ecosystem theory for the patient-centered supporting system for caregivers of Alzheimer disease in China. Chin. Gen. Pract. 2016, 19, 997–1001, 1005. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Ma, W.; Li, H.; Cao, W. Study on the Influencing Factors of Self—Assessment of Health Status of Rural Poverty-stricken Residents due to Illnesses from the Perspective of Social Ecosystem Theory. Med. Soc. 2019, 32, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Huang, Y. Realising equity in maternal health: China’s successes and challenges. Lancet 2019, 393, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Liang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Jiao, M.; Mao, J.; Wu, Q. Sociodemographic determinants of maternal health service use in rural China: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Martinez-Alvarez, M.; Shallcross, D.; Pi, L.; Tian, F.; Pan, J.; Ronsmans, C. Barriers to accessing maternal healthcare among ethnic minority women in Western China: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Diao, Y.; You, L.; Wu, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y. The influence of basic public health service project on maternal health services: An interrupted time series study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Lu, J.; Hao, M.; Zhang, C.; Sun, M.; Li, X.; Chang, F. Factors impacting the use of antenatal care and hospital child delivery services: A case study of rural residents in the Enshi Autonomous Prefecture, Hubei Province, China. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2015, 30, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W. Investigation and analysis on equity of prenatal health care service utilization. Matern. Child Health Care China 2013, 28, 581–583. [Google Scholar]

- Duerden, M.; Witt, P.A. An ecological systems theory perspective on youth programming. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2010, 28, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Singh, N.S.; Powell-Jackson, T.; Nash, S.; Yang, M.; Guo, S.; Fang, H.; Alvarez, M.M.; Liu, X.; et al. Progress and challenges in maternal health in western China: A Countdown to 2015 national case study. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, E523–E536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.L.; Xu, L.; Guo, Y.; Ronsmans, C. Socioeconomic inequalities in hospital births in China between 1988 and 2008. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Kaur, R.; Prabhakar, P.K.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, R. Improving Perinatal Health: Are Indian Health Policies Progressing In The Right Direction? Indian J. Community Med. 2017, 42, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koblinsky, M.A.; Campbell, O.; Heichelheim, J. Organizing delivery care: What works for safe motherhood? Bull. World Health Organ. 1999, 77, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Solnes Miltenburg, A.; Kvernflaten, B.; Meguid, T.; Sundby, J. Towards renewed commitment to prevent maternal mortality and morbidity: Learning from 30 years of maternal health priorities. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2023, 31, 2174245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withers, M.; Kharazmi, N.; Lim, E. Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: A review of the evidence from Asian countries. Midwifery 2018, 56, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, Y.; Horiuchi, S. Factors influencing the use of antenatal care in rural West Sumatra, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, A.; Basu, G.; Ballard, M.; Griffiths, T.; Kentoffio, K.; Niyonzima, J.B.; Sechler, G.A.; Selinsky, S.; Panjabi, R.R.; Siedner, M.J.; et al. Remoteness and maternal and child health service utilization in rural Liberia: A population-based survey. J. Glob. Health 2015, 5, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Yu, T.; Gu, H.; Kou, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Cui, N.; Bai, L. Factors Associated With Prescribed Antenatal Care Utilization: A Cross-Sectional Study in Eastern Rural China. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2019, 56, 1142418267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Ansah, E.K.; Okawa, S.; Enuameh, Y.; Yasuoka, J.; Nanishi, K.; Shibanuma, A.; Gyapong, M.; Owusu-Agyei, S.; Oduro, A.R.; et al. Effective Linkages of Continuum of Care for Improving Neonatal, Perinatal, and Maternal Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e139288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Huang, K.; Long, X.; Tolhurst, R.; Raven, J. Low postnatal care rates in two rural counties in Anhui Province, China: Perceptions of key stakeholders. Midwifery 2011, 27, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.L.; Shi, G.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Luo, H.; Shen, J.; Yin, H.; Guo, Y. An Impact Evaluation of the Safe Motherhood Program in China. Health Econ. 2010, 19, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Li, X.; Dai, L.; Zeng, W.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; Zhou, R.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J. The Changes in Maternal Mortality in 1000 Counties in Mid-Western China by a Government-Initiated Intervention. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, J. Generating political priority for maternal mortality reduction in 5 developing countries. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang’At, E.; Mwanri, L. Healthcare service providers’ and facility administrators’ perspectives of the free maternal healthcare services policy in Malindi District, Kenya: A qualitative study. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, L.; Zhao, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. National Essential Public Health Services Programs over the Past Decade Research Report Two: Progress and achievements of the implementation of National Essential Public Health Services Programs over the past decade. Chin. Gen. Pract. 2022, 25, 3209–3220. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Ding, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Strengthening the maternal and child health system in remote and low-income areas through multilevel governmental collaboration: A case study from Nujiang Prefecture in China. Public Health 2020, 178, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. National Essential Public Health Services Programs over the Past Decade Research Report Three: Challenges and recommendations of implementation National Essential Public Health Services Programs over the past decade. Chin. Gen. Pract. 2022, 25, 3221–3231. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Yan, H.; Reija, K.; Li, Q.; Xiao, S.; Gao, J.; Zhou, Z. Equity in use of maternal health services in Western Rural China: A survey from Shaanxi province. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1991–1999 (n = 94) | 2000–2008 (n = 306) | 2009–2015 (n = 373) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)/ ± s | n (%)/ ± s | n (%)/ ± s | ||

| Micro-factors: Individuals’ characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤24 | 65 (69.1) | 172 (56.2) | 143 (38.3) | |

| 25–29 | 24 (25.5) | 81 (26.5) | 125 (33.5) | |

| ≥30 | 5 (5.3) | 53 (17.3) | 105 (28.2) | <0.001 |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| Ethnic minority | 54 (57.4) | 140 (45.8) | 181 (48.5) | |

| Han | 40 (42.6) | 166 (54.2) | 192 (51.5) | 0.140 |

| Education | ||||

| Below high school | 77 (81.9) | 261 (85.3) | 272 (72.9) | |

| High school or above | 17 (18.1) | 45 (14.7) | 101 (27.1) | <0.001 |

| Meso-factors: Family factors | ||||

| Annual household income | ||||

| ≤CNY 10,000 | 79 (84.0) | 178 (58.2) | 102 (27.3) | |

| CNY 10,000–50,000 | 14 (14.9) | 112 (36.6) | 182 (48.8) | |

| >CNY 50,000 | 1 (1.1) | 16 (5.2) | 89 (23.9) | <0.001 |

| Health insurance | ||||

| No | 90 (95.7) | 225 (73.5) | 27 (7.2) | |

| Yes | 4 (4.3) | 81 (26.5) | 346 (92.8) | <0.001 |

| Meso-factors: Community factors | ||||

| Road conditions in the village | ||||

| Poor | 90 (95.7) | 225 (73.5) | 27 (7.2) | |

| Good | 4 (4.3) | 81 (26.5) | 346 (92.8) | <0.001 |

| Meso-factors: Healthcare factors | ||||

| Number of MCH staff in township health center | 1.76 ± 1.013 | 3.48 ± 1.044 | 5.87 ± 1.411 | <0.001 |

| Variables | Prenatal Examinations (≥5 Visits) | Hospital Births | Postpartum Visits (≥1 Visits) | CMHS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Micro-factors: Individuals’ characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤24 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 25–29 | 1.334 (0.852, 2.087) | 1.909 (0.912, 3.997) | 1.002 (0.647, 1.552) | 1.216 (0.751, 1.969) |

| ≥30 | 1.057 (0.656, 1.704) | 0.621 (0.279, 1.383) | 1.050 (0.657, 1.677) | 1.02 6(0.618, 1.701) |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| Ethnic minority | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Han | 1.010 (0.721, 1.414) | 1.087 (0.647, 1.827) | 0.966 (0.695, 1.341) | 1.084 (0.746, 1.573) |

| Education | ||||

| Below high school | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| High school or above | 1.400 (0.911, 2.153) | 3.234 (1.420, 7.368) ** | 1.499 (0.993, 2.265) | 1.928 (1.248,2.977) ** |

| Meso-factors: Family factors | ||||

| Annual household income | ||||

| ≤CNY 10,000 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| CNY 10,000–50,000 | 1.743 (1.201, 2.531) ** | 1.305 (0.740, 2.302) | 1.263 (0.873, 1.829) | 1.657 (1.078, 2.545) * |

| >CNY 50,000 | 1.784 (1.012, 3.143) * | 2.426 (0.490, 12.026) | 1.442 (0.831, 2.500) | 1.958 (1.115, 3.441) * |

| Health insurance | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.092 (0.704, 1.694) | 5.780 (2.773, 12.048) *** | 1.197 (0.771, 1.857) | 1.377 (0.821, 2.309) |

| Meso-factors: Community factors | ||||

| Road conditions in the village | ||||

| Poor | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Good | 1.562 (1.023, 2.385) * | 2.421 (1.406, 4.171) ** | 1.073 (0.702, 1.640) | 2.193 (1.231, 3.907) ** |

| Meso-factors: Healthcare factors | ||||

| Number of MCH staff in township health center | 1.198 (1.031, 1.390) * | 1.659 (1.269, 2.169) *** | 1.305 (1.128, 1.510) *** | 1.393 (1.191, 1.630) *** |

| Macro-factors: MCH programs | ||||

| Before RMMENT (before 2000) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| RMMENT (2000–2008) | 1.933 (0.891, 4.195) | 2.718 (1.200, 6.155) * | 0.864 (0.429, 1.741) | 4.520 (0.588, 34.752) |

| BPHS (2009–2015) | 4.510 (1.743, 11.666) ** | 21.891 (3.655, 131.117) ** | 1.516 (0.627, 3.664) | 8.949 (1.087, 73.648) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Lu, J. Changes and Determinants of Maternal Health Services Utilization in Ethnic Minority Rural Areas in Central China, 1991–2015: An Ecological Systems Theory Perspective. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1374. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101374

Zhang C, Lu J. Changes and Determinants of Maternal Health Services Utilization in Ethnic Minority Rural Areas in Central China, 1991–2015: An Ecological Systems Theory Perspective. Healthcare. 2023; 11(10):1374. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101374

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Changli, and Jun Lu. 2023. "Changes and Determinants of Maternal Health Services Utilization in Ethnic Minority Rural Areas in Central China, 1991–2015: An Ecological Systems Theory Perspective" Healthcare 11, no. 10: 1374. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101374