Two Puzzles, a Tour Guide, and a Teacher: The First Cohorts’ Lived Experience of Participating in the MClSc Interprofessional Pain Management Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Participants

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

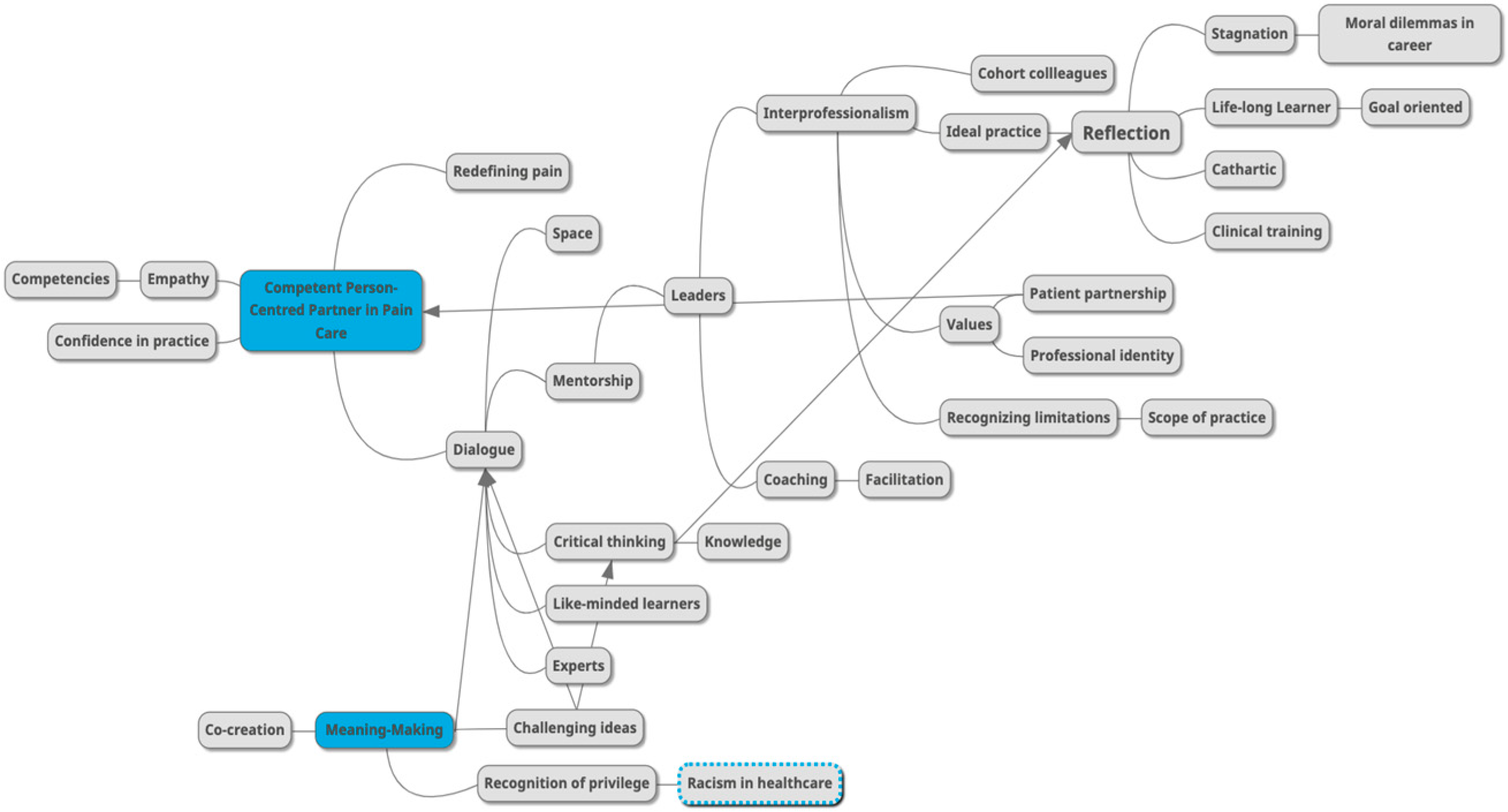

3.1. Themes

3.1.1. Theme 1. Reflection on Stagnation in Professional Disciplines

“Well, I thought as a sole practitioner, I felt like I was a little bit on an island in terms of keeping up-to-date and there’s only so much that I can do for continuing education, and I felt like that was getting a little bit stale”—P003.

“I’m extremely goal-oriented…this might be a fault to some extent. I always wanted something else. I’m always like, ‘OK, what’s next? How can I challenge myself?’ I never want to be stagnate in my career. So, this kind of came to be an option and…the pieces aligned and then it worked”—P004.

“I was just getting very sort of frustrated with continuing education that the state of it in [clinical profession]. Anyway, I was really big into the soft tissue side of things…and I found that getting very stale and repetitive. You know, it’s almost like they weren’t keeping up with the current loop of research that I was reading on the internet, and I found that to be a little frustrating because if I’m gonna spend all this money, I want to do it just for something that is worthwhile and current”—P003.

“It’s important to me to become the best clinician I can. I thought this was a good opportunity to pursue becoming…an expert in pain”—P001.

“So, I think it was just sort of the hope for the growth and expanding on sort of my skills as a healthcare provider to sort of be continuing on that journey and grow there. I think one of my past sort of supervisors used to say that ‘as soon as you feel like you have nothing left to learn, it’s time to get out of the profession.’ And so, I think… I really just like learning and really enjoy learning, but I think it’s also, as a healthcare provider, we have this responsibility to keep growing and to not stop. So, I think part of my hope was just that I could use sort of where I’m coming from, but then also, the resource in this program to just sort of keep expanding on that and become a better healthcare provider for people that experience pain”—P002.

3.1.2. Theme 2. Meaning-Making through Dialogue with Like-Minded Learners

“I enjoyed the program because of my conversations with the people in it”—P004.

“I found it to be very stimulating intellectually and the other learners…and with anyone that we really talked to was very friendly and open with communication so, I found it to be something that I looked forward to. You know, it was a lot of work, but I enjoyed doing it and I would definitely do it again and I’d recommend it to anybody”—P003.

“We were able to have weekly or almost weekly meetings with the group. And so, I think the process of having that time for discussion to really break down the material, speak with different experts in their fields and learn from them, I think that was another key area that I think there’s a few other opportunities to really touch base with so many different experts on a weekly basis…that’s really challenging on your own. I don’t think we would have gotten that opportunity outside of this program to any significant extent, especially in such a small group where we could have those individual conversations with the expert. So, I think those pieces really stood out for me as it’s quite… [a] rewarding experience in being able to kind of really build working relationships with these other healthcare providers that you’re learning with and from at the same time”—P002.

“It is nice to just be…among other similar minded clinicians”—P001.

“I think some of the most positive things that I took…it’s definitely in terms of improving my own confidence with my own abilities. It’s really good to go through a rigorous program to kind of prove that…I do deserve to have a seat at the table, and I can have these meaningful conversations with other experts, so I think it’s been huge for my confidence as well”—P001.

“I think we have a tendency to focus on some of the harder or difficult moments because they really make an impact on us, but I think those are the ones that almost forced charge. And so, I think without some of those or part of the reason I wanted to do this program was the extra chance to be sort of mentored and…the competencies did [that] through that growth”—P002.

“I feel like the whole program itself was a bit of an ah-ha moment. But I think… a few of them for me were really sort of some of the papers that we kind of connected with themes throughout and how we sort of framework these experiences to sort of make sure that we can intervene in a way that makes sense for that person. So, I think some of the papers around the radar plot and sort of how do we integrate those within patient care? I think a lot of us do it to some extent, sort of intuitively, but then having that visual was sort of a bit of an ah-ha moment for me. It’s an easy way then to kind of explain to someone else of, ‘this is why we intervened here’ because this is the pain drivers”—P002.

3.1.3. Theme 3. Challenging Ideas and Critical Thinking at Play

“I didn’t feel like I was back in [clinical training] where you just kind of accept everything. I’m listening, but I’m challenging everything that they’re kind of suggesting and not just taking it as it is…I’m able to listen to some really great thinkers and I’m also able to still kind of challenge them”—P001.

“And sort of really almost challenging some of the beliefs that I had had about our interest, like the interventions that [clinical profession] use. And so, I think it was really in that sense, it was sort of stepping outside of my comfort zone because I have done some of that work in the past, but I don’t think to the same depth that I did it within this program in route of reassessing… It was really sort of that level of discomfort of grappling with…certain things and really sort of challenging my own comfort and beliefs about what we’re doing”—P002.

“I just assumed that a good recovery is you either get back to who you were or better and those are the only two options that were satisfactory, acceptable for me, but I think being able to really engage in that conversation and have that challenge, and also open up the options for people that there’s other ways that people can have good recoveries and I don’t need to tie my own…expectations of myself, and that’s not a reflection of myself…that was the first and biggest ah-ha moment or kind of paradigm shifting moment where I guess my perspective as a clinican changed”—P001.

“I like to question things and you know really make sure that what’s being said is valid”—P004.

“I remember there was a few [activities] that were definitely more intellectually hard to grasp [including] the Seven Step framework to a research paper and then also to the pain model. I remember those took quite a bit of time because I wasn’t sure what the expectations were so…I had to really think outside of the box and make sure I was looking at the big picture”—P003.

“[Portfolio] almost sort of reinforced what you’ve learned in one solid space, and so, having that opportunity to compile it all together was, I think, really quite powerful as a learner and quite a big [accomplishment] at the end of it”—P002.

“I found most of them [learning activities] to be really meaningful practices. So, I appreciated that, and I think it was nice to be able to create something…I guess there are some thoughts there that felt like I’m not doing this for myself anymore, whereas some of them felt deeply personal, that was such a wonderful thought experiment for me and the act of me going through it really was helpful for my own growth compared to some that felt like I’m just trying to prove to some external evaluator that I’m OK at something”—P001.

“I’m very proud of what I did. You know, I put a lot of work into it [portfolio]…I’d like to go back and read it, and I’m more than happy to let anyone have a look at it, but I definitely, towards the end of it, is when it really started to sink in that a lot of work went into that, so I felt really good about everything I had in there. You know some exercises were better than others, but everything in there I definitely feel good about”—P003.

3.1.4. Theme 4. The Spirit of Interprofessional Care includes Patient Partnership

“You don’t want the patient to feel like they’re in the middle of everyone and everyone’s sort of on their own little island doing their own thing. You know, even now, being in a solo practice, I know if I had a difficult patient, I could 100% trust that I could write anyone in our group [fellow cohort members] to get their opinion and I would value it and see what they had to say. And maybe it would make me think of something that I wasn’t doing or maybe that they could help them, or they knew somebody that could help this patient. So, I think that’s incredibly valuable”—P003.

“How we approach things and then just even so much of how we can learn from each other and then how we can sort of synthesize all of that information that we’ve learned together to really work better together, and I think that’s one of the key pieces that I feel like I’ve learned a lot as well. Now, we have sort of the shared language of how we work together effectively. What does that structure look like and how can we best serve patients within that sort of interprofessional collaboration framework?”—P002.

“This was a consistent thing that came out that might come up with others as well, possibly, but something we had kind of spoken about is, most of us, we don’t work in super interdisciplinary teams…we’re very siloed and so our interaction with other professionals is so limited right now with where I am. I could say I’ve maybe been more aware of when we’ve kind of reached the limits of my abilities and we could be quicker to reach out to other people”—P001.

“My ideal practice would certainly involve some interprofessional collaboration”—P003.

“I think it’s certainly a process that I still feel like will continue for myself just to sort of continue to grow and learn about as well. But I definitely think I feel like I do have those better understandings of my own boundaries and how I can even advocate for someone with about healthcare provider as well, and sort of merging that together…I mean you could come up with the perfect treatment plan or management strategies for someone, but if it doesn’t actually make sense for them and it’s not something that’s in line with their values, it’s pretty much useless…I think at the end of the days it’s always taking that patient or person first approach with them”—P002.

“I think the things that I really value is, huh, this might be outdates, but I think we really have a duty to do no harm and that really is a really broad thing that extends beyond just what we’d like to do with people. So, I think really making sure we are…trying to help people in a way that is most impactful for them both now and in the future. It’s really important. So, part of that means being mindful of your language, how you frame things, how you’re empowering people, and how you’re helping support the development of their own self-efficacy”—P001.

“I still think I have my interpersonal skills [that] I think are pretty good for the most part with most patients, so I can build, I would say, fairly consistent therapeutic alliances with people, which builds trust”—P004.

“Well, how I view myself, I find that I apply a lot of the same techniques and active listening. I can use that in my everyday life as well. So, again, I think I’m pretty easy-going and it certainly helped in interacting with people I feel overall. I can probably connect with people a little bit better and I’m comfortable doing that because we’ve had those experiences in those conversations. There was one about oppression and privilege, concepts that I hadn’t heard about, that I hadn’t really given too much actual thought to and then once we had those conversations, it certainly made me think about how I come across and putting myself in other people’s shoes. So, I think it’s helped shape my identity that way that I’m hopefully a better person because of that”—P003.

“I think my professional identity is really based in just sort of supporting people where they’re at and supporting their ability to have…access… to a management strategy that makes sense within the context of their values and belief systems…So, I really just kind of see it coming down to where I can support people within their value system and based on what sort of pain drivers are going on alongside these other healthcare providers as well and sot of always working together with that person at the centre of their care”—P002.

“Crazy ambitious goal, I do want to contribute to systemic change of how people with pain are cared for and I want healthcare to be more…evidence-based, more transparent…have patient and practitioner on an equal level…I much prefer to coach on the same level with people. So, I would love to see people with pain being more empowered and getting good care”—P001.

3.1.5. Theme 5. Becoming a Competent Person-Centred Partner in Pain Care

“I think our competencies were a pretty good place to start, that those are things that people should embody, but I think you do need to be knowledgeable, there is a lot you need to do to be an expert in helping people with pain, and that’s hard to help people if you don’t even know the game that you’re playing”—P001.

“That’s the neat thing about competencies is that you can kind of come in at your own level of comfort and then sort of grow from there or demonstrate competency within that framework. So, I think that I had sort of like a mixed comfort with some of them. I don’t think I was a pain expert to any degree. I think that one is one that you sort of, as the field continues to grow or sort of expand and change, I think that is one that kind of keeps developing over time…some of the ones around empathic care or self-awareness and reflexivity, I think I came in with a bit of comfort around them already. Just sort of by way of my profession and training and sort of how we’ve sort of gone about that. Then pain research and interprofessional collaboration, a bit of experience there, but just sort of expanding on that throughout the program I think and kind of continuing to develop it”—P002.

“Initially, I was a little unsure of exactly what it entailed, but you know shortly after we got started, I realized it would be an awesome addition to my clinical practice and I found myself applying what we were learning almost immediately, which was pretty amazing to do be able to do that. So, definitely it’s impacted the way that I practice”—P003.

“I would say I definitely feel like I’ve shifted and changed and grown as a healthcare provider in the field of pain management. I think that has certainly shifted, not only sort of my professional life, but I think it’s also sort of spilled over into my personal life as well. I think it’s sort of inevitable in a lot of ways of just when you’re focusing on certain areas…you know how I’ve gotten here and sort of what my biases are and sort of checking that I think it’s hard to capture in one or two sentences sort of how it’s impacted me, but I think it’s certainly made me a stronger healthcare provider, but also more aware in my personal life as well”—P002.

“I think this program…to be honest…maybe [was an] expensive lesson, but it kind of reaffirmed for me that no matter what you read and what you’ve learned and what kind of lens [which] you view pain, if you can’t connect with people, and if you just feel like you’re not able to amend to the blue collar worker or the CEO white collar person and [be] kind of a shapeshifter on a daily basis, you’re going to struggle regardless of what you know”—P004.

“May I say, I think I’ve become even more accepting of the people I work with, the uncertainty of it all, the complexity of it all, the things I do and do not have control over. I think it’s maybe the past year has just accentuated some of the things that I came in with…I have some values that I abide by, and I’ve double downed on a lot of those, so it’s made me feel even more sure about that actually and even more thoughtful with patients and more deliberate with patients about how we go about things”—P001.

“The role that is hard to play for people is more as a guide. They’re there to keep people safe and try and lead them in a way that they want to and that maybe they can’t always see for themselves first, so I might have to light the way or lead them a little bit and just walking with them. Never carrying them”—P001.

“It’s almost a puzzle piece to some extent too. You’re a part of a management plan or you are part of that kind of pain management piece, but I don’t see myself as being the entire piece of the puzzle, and I think it’s sort of working alongside those other people and sort of fitting together what it means within the context of that person’s day-to-day life and sort of how we can support them as best as possible. A puzzle piece photo of a body”—P002.

“I guess I look at myself as a teacher because many times I’d say the vast majority of times people haven’t been told what’s going on in any meaningful way…And they haven’t been told what the diagnosis is, what it means, what the structures are involved”—P003.

“I’m thinking is like in terms of my role in treating pain. It’s like a puzzle. For me, I want so desperately want the pieces to fit, so it makes a whole picture of what the puzzle is, but the issue is in terms of like this puzzle is sometimes you don’t have the box to reference the photo to”—P004.

4. Discussion

4.1. Life-Long Learning

4.2. Dialogue

4.3. Ideal Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gruppen, L.D.; Burkhardt, J.C.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Funnell, M.; Haftel, H.M.; Lypson, M.L.; Mullan, P.B.; Santen, S.A.; Sheets, K.J.; Stalburg, C.M.; et al. Competency-Based Education: Programme Design and Challenges to Implementation. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.P.; Stinson, J.; Campbell, F.; Stevens, B.; Wagner, S.J.; Simmons, B.; White, M.; van Wyk, M. A Novel Pain Interprofessional Education Strategy for Trainees: Assessing Impact on Interprofessional Competencies and Pediatric Pain Knowledge. Pain Res. Manag. 2015, 20, e12–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajjawi, R.; Higgs, J. Using Hermeneutic Phenomenology to Investigate How Experienced Practitioners Learn to Communicate Clinical Reasoning. Qual. Rep. 2007, 12, 612–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, S.M.; Young, H.M.; Lucas Arwood, E.; Chou, R.; Herr, K.; Murinson, B.B.; Watt-Watson, J.; Carr, D.B.; Gordon, D.B.; Stevens, B.J.; et al. Core Competencies for Pain Management: Results of an Interprofessional Consensus Summit. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnitt, R.; Partridge, C. Ethical Reasoning in Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy. Physiother. Res. Int. 1997, 2, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Manen, M. Phenomenology of Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pitre, N.Y.; Kushner, K.E.; Raine, K.D.; Hegadoren, K.M. Critical Feminist Narrative Inquiry: Advancing Knowledge through Double-Hermeneutic Narrative Analysis. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2013, 36, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponterotto, J.G. Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology: A Primer on Research Paradigms and Philosophy of Science. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. On Critical Reflection. Adult Educ. Q. 1998, 48, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Learning as Discourse. J. Transform. Educ. 2003, 1, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryssenaar, J.; Perkins, J. From Student to Therapist: Exploring the First Year of Practice. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2001, 55, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsella, E.A.; Caty, M.-E.; Ng, S.L.; Jenkins, K. Reflective Practice for Allied Health: Theory and Applications. In Adult Education and Health; English, L., Ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012; pp. 210–228. [Google Scholar]

- Trede, F.; Macklin, R.; Bridges, D. Professional Identity Development: A Review of the Higher Education Literature. Stud. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, S.; Kinsella, E.A. Occupational Identity: Engaging Socio-Cultural Perspectives. J. Occup. Sci. 2009, 16, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. The Ethics of Authenticity; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; ISBN 978-0-674-26863-0. [Google Scholar]

- Buytendijk, F.J.J. The Meaning of Pain. Philos. Today 1957, 1, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePoy, E.; Cook Merrill, S. Value Acquistion in Occupational Therapy Curriculum. Occup. Ther. J. Res. 1988, 8, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slay, H.S.; Smith, D.A. Professional Identity Construction: Using Narrative to Understand the Negotiation of Professional and Stigmatized Cultural Identities. Hum. Relations 2011, 64, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Trede, F. Response to Commentary on ‘Practical Concerns of Educators Assessing Reflections of Physiotherapy Students. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2014, 19, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, H.S. Professional Identity (Trans)Formation in Medical Education: Reflection, Relationship, Resilience. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Critical Reasoning and Creativity | Empathic Practice and Reasoning | Self-Awareness and Reflexivity |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Efficiently and effectively searches appropriate sources to find relevant knowledge | 2.1 Takes perspective and can subjectively experience another person’s psychological state and intrinsic emotions | 3.1 Explores and identifies critical incidents, both personal and professional |

| 1.2 Efficiently and effectively summarizes a peer-reviewed paper | 2.2 Identifies and understands a person’s feelings and perspective | 3.2 Describes and reflects on cultural and societal biases |

| 1.3 Evaluates new knowledge for trustworthiness and risk bias | 2.3 Constructs appropriate responses to convey an understanding of another’s perspective | 3.3 Uses reflection to develop a deeper understanding of previous critical incidents |

| 1.4 Interprets the findings of research from a critical social science lens | 2.4 Behaves in a non-judgmental, compassionate, tolerant, and empathic way | 3.4 Moves beyond reflection and critical thinking to benign introspection |

| 1.5 Synthesizes research evidence with clinical experience | 2.5 Tracks changes in the quality of the therapeutic alliance | 3.5 Sees self through the eyes of others |

| 1.6 Creates new relevant, defensible, ethically, and socially just knowledge | ||

| Interprofessional Collaboration | Pain Expertise | |

| 4.1 Demonstrates partnership in an interprofessional team | 5.1 Describes and interprets pain from a biopsychosocial lens | |

| 4.2 Demonstrates teamwork and collaboration | 5.2 Collects information to evaluate and interpret intervention pain | |

| 4.3 Interprets and understands patient health through social determinants of health and social equity | 5.3 Appraises, synthesizes, and summarizes the biology of pain | |

| 4.4 Advocates on behalf of patients | 5.4 Appraises, synthesizes, and summarizes the psychology of pain | |

| 4.5 Establishes an effective working alliance with patients | 5.5 Appraises, synthesizes, and summarizes socio-cultural aspects of pain | |

| 5.6 Conducts a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s pain experience | ||

| 5.7 Establishes a prognosis/theragnosis for patients in pain | ||

| 5.8 Synthesizes information from assessments to intervention plans | ||

| 5.9 Selects a published model of pain to critically interpret |

| Research Questions | Objectives |

|---|---|

| 1. What motivated you to enroll in this program? Prompts:

| Determine the experience for applying to the new alternative program. Determine the reasoning for applying to the new alternative program. Identify what experiences led the participants to apply. Identify if the participants’ expectations were met in regard to the program. |

| 2. Please describe your experience in the Interprofessional Pain Management program. Prompts:

| Interview learners on their lived experience of learning about pain in the MClSc Interprofessional Pain Management (IPM) program. Identify how participants’ understandings of pain has changed. Interview participants to determine if they experienced challenges while enrolled in the IPM program. |

| 3. In what ways have your experiences in the program changed how you think about pain or pain management? Prompts:

| Identify participants’ personal beliefs of pain prior to enrolling in the program. Identity current personal beliefs of pain while in the program. Determine if the experience of being in the program has changed participants’ clinical practice. Determine if the experience of being in the program has changed participants’ views of pain overall. |

| 4. In what ways have your experiences in the program shaped how you think about yourself as a pain care provider? Prompts:

| Determine how participants define their professional identities. Identify if the participants feel that the IPM program will impact their future clinical practice. Determine if participants’ beliefs and assumptions about pain changed since enrolling in the IPM program. In what ways was participation IPM program perceived by participants to shape their professional identity? |

| 5. Can you provide a metaphor for yourself as a pain care provider? Prompts

| Identify any metaphors the participants relate to as pain care providers. Determine participants’ ideal pain care practice. Identify if there are changes in participants’ care since being enrolled in the program. Determine if participants have changed how they view practice as a pain care provider. |

| 6. Do you have any final thoughts you would like to share? | Overall thoughts of the program. Any additional comments to the previous questions asked? Time for participants to ask the interviewer questions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leyland, Z.A.; Walton, D.M.; Kinsella, E.A. Two Puzzles, a Tour Guide, and a Teacher: The First Cohorts’ Lived Experience of Participating in the MClSc Interprofessional Pain Management Program. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101397

Leyland ZA, Walton DM, Kinsella EA. Two Puzzles, a Tour Guide, and a Teacher: The First Cohorts’ Lived Experience of Participating in the MClSc Interprofessional Pain Management Program. Healthcare. 2023; 11(10):1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101397

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeyland, Zoe A., David M. Walton, and Elizabeth Anne Kinsella. 2023. "Two Puzzles, a Tour Guide, and a Teacher: The First Cohorts’ Lived Experience of Participating in the MClSc Interprofessional Pain Management Program" Healthcare 11, no. 10: 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101397

APA StyleLeyland, Z. A., Walton, D. M., & Kinsella, E. A. (2023). Two Puzzles, a Tour Guide, and a Teacher: The First Cohorts’ Lived Experience of Participating in the MClSc Interprofessional Pain Management Program. Healthcare, 11(10), 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101397