Psychometric Evaluation of the Korean Version of the Perceived Costs and Benefits Scale for Sexual Intercourse

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

3. Measurements

3.1. Perceived Costs and Benefits Scale (PCBS) for Sexual Intercourse

3.2. Translation Procedures

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. General Characteristics of Participants

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Mean Scores of the K-PCBS

4.3. Validity Test for the K-PCBS

Content Validity

4.4. Construct Validity

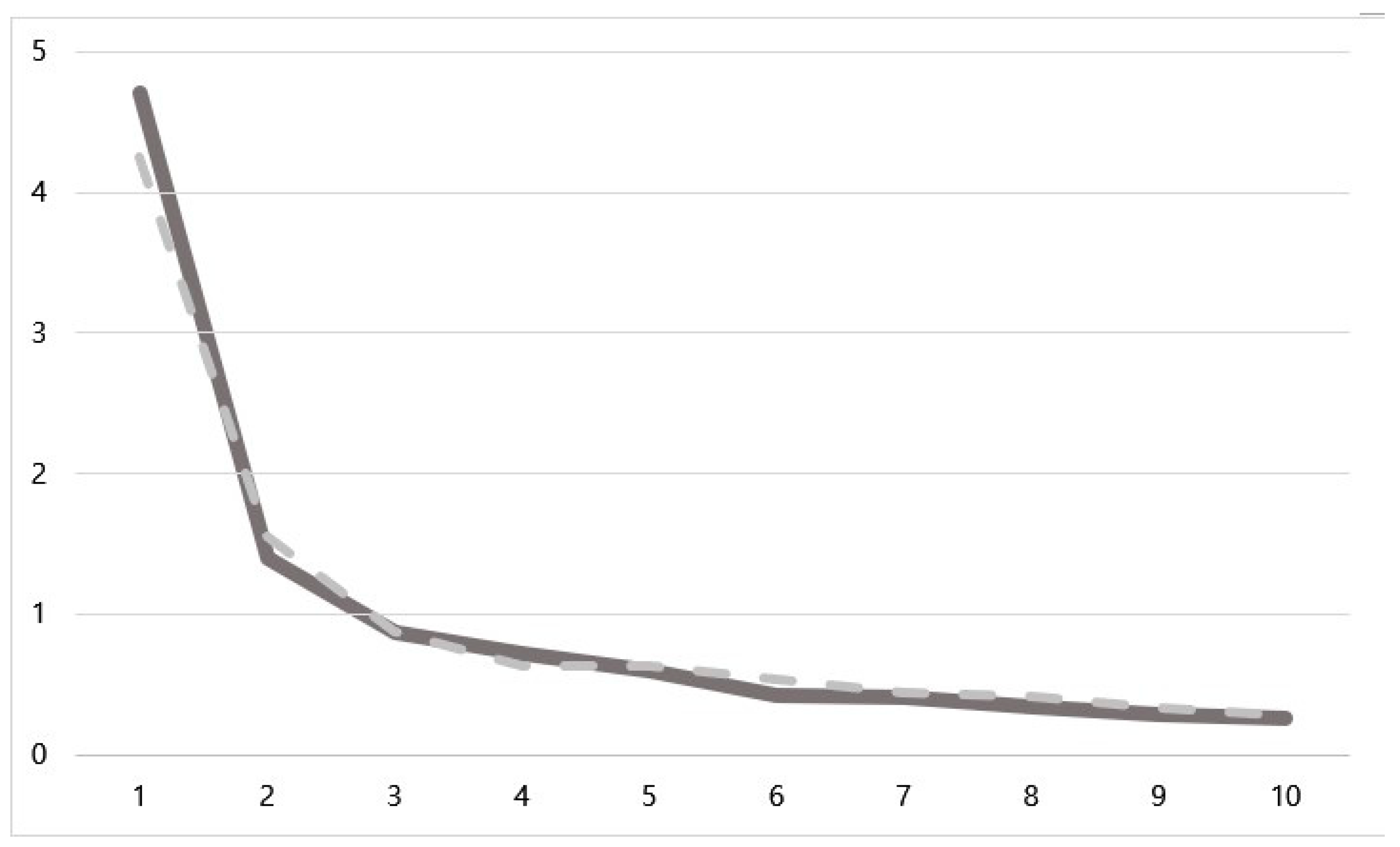

EFA with Varimax Rotation

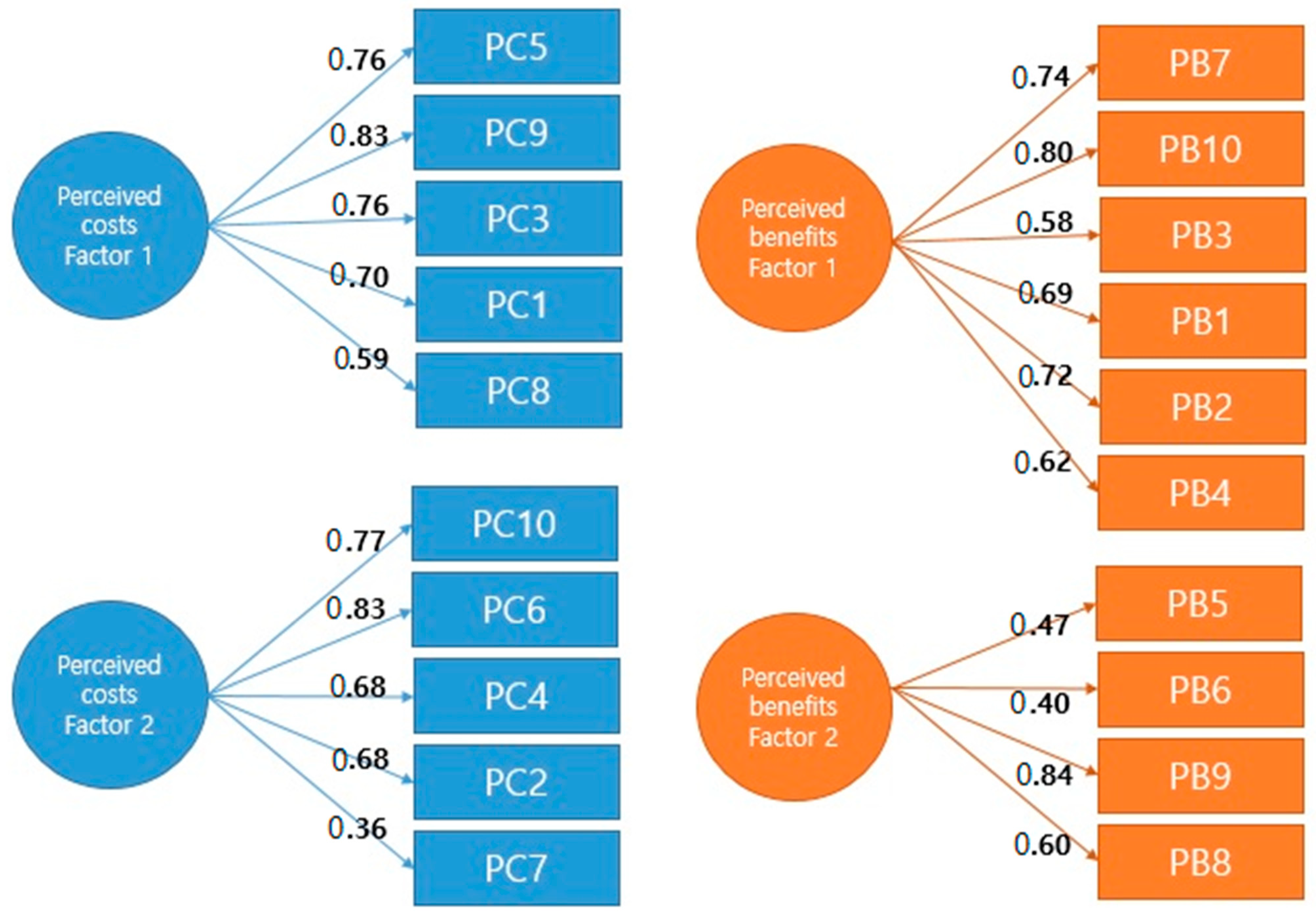

4.5. Measuring Model Using CFA

4.6. Reliability for the K-PCBS

4.7. Descriptive Statistics of the K-PCBS Using Two Sub-Categories

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Finer, L.B.; Phibin, J.M. Sexual initiation, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among young adolescents. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 86–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y. Factors affecting contraceptive use among adolescent girls in South Korea. Child. Health Nurs. Res. 2017, 23, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeun, E.J.; Jeon, M.S. Knowledge and attitude of sex in undergraduate students. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2018, 120, 6193–6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Lee, E.M.; Lee, H.Y. Sexual double standard, dating violence recognition, and sexual assertiveness among university students in South Korea. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Cameron, L.D.; Hamilton, K.; Hankonen, N.; Lintunen, T. Changing behavior using the theory of planned behavior. In The Handbook of Behavior Change; Ajzen, I., Schmidt, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.; Rimal, R.N. Social norms: A review. Rev. Comm. 2016, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S.R.; Schmiege, S.; Bull, S. Actual versus perceived peer sexual risk behavior in online youth social networks. Transl. Behav. Med. 2013, 3, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peçi, B. Peer influence and adolescent sexual behavior trajectories: Links to sexual initiation. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2017, 4, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boislard, M.A.; van de Bongardt, D.; Blais, M. Sexuality (and lack thereof) in adolescence and early adulthood: A review of the literature. Behav. Sci. 2016, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 105–151. [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, M.S.B. ABC of content validation and content validity index calculation. Educ. Med. J. 2019, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, S.A.; Silverberg, S.B.; Kerns, D. Adolescents’ perceptions of the costs and benefits of engaging in health-compromising behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 1993, 22, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Oh, J. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of a tool to measure uncivil behavior in clinical nursing education. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2016, 22, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Lee, J.M.; Min, H.Y. An integrative literature review on sex education programs for Korean college students. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 26, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.O.; Yeom, G.J.; Kim, M.J. Development a sex education program with blended learning for university students. Child. Health Nurs. Res. 2018, 24, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. Sexual Behaviors and sexual experience of adolescents in Korea. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2016, 17, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Kang, K.W.; Jeong, G.H. Self-efficacy and sexual autonomy among university students. J. Korean Public. Health Nurs. 2012, 26, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widman, L.; Nesi, J.; Kamke, K.; Choukas-Bradley, S.; Stewart, J.L. Technology-based interventions to reduce sexually. J. Adolesc. Health. 2018, 62, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Choi, Y. Contraceptive use among korean high school adolescents: A decision tree model. J. Sch. Nurs. 2023, 39, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, A.R.; Chun, S.S. Comparing sexual attitude, sexual initiation and sexual behavior by gender in Korean college students. Korean Assoc. Health Med. Sociol. 2015, 18, 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.E.; Chae, H.J. Knowledge and educational need about contraceptives according to sex in college students. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2010, 16, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Preventing Early Pregnancy through Appropriate Legal, Social and Economic Measures. 2018. Available online: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/adolescence/laws/en/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Vasilenko, S.A.; Lefkowitz, E.S.; Welsh, D.P. Is sexual behavior healthy for adolescents? A conceptual framework for research on adolescent sexual behavior and physical, mental, and social health. New Dir. Child. Adolesc. Dev. 2014, 2014, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upchurch, D.M.; Aneshensel, C.S.; Sucoff, C.A.; Levy-Storms, L. Neighborhood and family contexts of adolescent sexual activity. J. Marriage Fam. 1999, 61, 920–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Have Not Had Sexual Intercourse (n = 119) | Have Had Sexual Intercourse (n = 108) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | n | (%) | Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | ||

| Gender | Female | 68 | 57.1 | 58 | 53.7 | ||

| Male | 51 | 42.9 | 50 | 46.3 | |||

| Age | 21.65 ± 1.898 (19–25) | 22.67 ± 1.635 (19–25) | |||||

| Grade level | Freshman | 24 | 20.2 | 10 | 9.3 | ||

| Sophomore | 36 | 30.3 | 17 | 15.7 | |||

| Junior | 27 | 22.7 | 41 | 38.0 | |||

| Senior | 32 | 26.9 | 40 | 37.0 | |||

| Current residential status | Alone | 13 | 10.9 | 23 | 21.3 | ||

| Family (Parents, brothers/sisters, or relatives) | 96 | 80.7 | 74 | 68.5 | |||

| Apartment with roommate (Same-sex and opposite sex) | 1 | 0.8 | 9 | 8.3 | |||

| Dormitory | 9 | 7.6 | 2 | 1.9 | |||

| Currently dating | Yes (Month) | 9 | 7.6 | 14.11 ± 18.977 (1–56) | 60 | 55.6 | 20.73 ± 15.159 (2–61) |

| No but in the past | 42 | 35.3 | 43 | 39.8 | |||

| Never | 68 | 57.1 | 5 | 4.6 | |||

| Method used to deal with sexual concerns or problems | Friend or senior | 42 | 35.3 | 61 | 56.5 | ||

| Parents or family | 14 | 11.8 | 6 | 5.6 | |||

| Internet, such as blogs or social media | 58 | 48.7 | 36 | 33.3 | |||

| Others (Alone, partner, hospital, seminars, etc.) | 5 | 4.2 | 5 | 4.6 | |||

| Sexual tolerance | Conservative | 33 | 27.7 | 15 | 13.9 | ||

| Moderate | 71 | 59.7 | 66 | 61.1 | |||

| Open | 15 | 12.6 | 27 | 25.0 | |||

| Siblings | No siblings (Only child) | 9 | 7.6 | 9 | 8.3 | ||

| Sister (Sister, younger sister) | 45 | 37.8 | 38 | 35.2 | |||

| Brother (Brother, younger brother) | 55 | 46.2 | 50 | 46.3 | |||

| Sisters and brothers | 10 | 8.4 | 11 | 10.2 | |||

| Most used method to obtain sex-related information | Friend or senior | 23 | 19.3 | 33 | 30.6 | ||

| Parents or family | 2 | 1.7 | 4 | 3.7 | |||

| Internet, such as blogs or social media | 84 | 70.7 | 68 | 62.9 | |||

| Others (Alone, book, seminars, etc.) | 10 | 8.3 | 3 | 2.8 | |||

| No. | Items | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived cost (n = 119) for those who have not had a sexual experience | ||||

| PC-1 | I do not have sex because I think it is morally wrong or against my religious beliefs. | 1.69 ± 0.841 | 1.165 | 0.796 |

| PC-2 | I do not have sex because it puts me at risk of contracting a sexually transmitted disease or AIDS. | 2.20 ± 0.935 | 0.091 | −1.075 |

| PC-3 | I do not have sex because my parents do not allow it. | 1.67 ± 0.845 | 1.201 | 0.834 |

| PC-4 | I do not have sex because I do not consider myself mature enough to do so. | 2.38 ± 1.066 | 0.090 | −1.234 |

| PC-5 | I do not have sex because my friends around me do not agree to have sex with me. | 1.55 ± 0.767 | 1.419 | 1.717 |

| PC-6 | I do not have sex because me or my partner may become pregnant. | 2.40 ± 1.003 | −0.012 | −1.091 |

| PC-7 | I do not have sex because I have not met someone I truly love. | 3.09 ± 0.911 | −0.937 | 0.238 |

| PC-8 | I do not have sex because having sex does not make me happy. | 2.15 ± 0.945 | 0.366 | −0.795 |

| PC-9 | I do not have sex because I feel guilty about having sex. | 1.73 ± 0.851 | 1.053 | 0.484 |

| PC-10 | I do not have sex because my or my partner’s unwanted pregnancy could ruin my future life. | 2.55 ± 0.946 | −0.074 | −0.875 |

| Total | 2.14 ± 0.617 | |||

| Perceived benefits (n = 108) for those who had a sexual experience | ||||

| PB-1 | I have sex because it helps me forget the problems I am facing. | 1.70 ± 0.800 | 0.701 | −0.729 |

| PB-2 | I have sex because it makes me feel like an adult. | 1.74 ± 0.802 | 0.617 | −0.826 |

| PB-3 | I have sex because I want to become pregnant or become a parent. | 1.42 ± 0.725 | 1.721 | 2.292 |

| PB-4 | I have sex to have or make friends of the opposite sex. | 1.64 ± 0.791 | 0.974 | 0.045 |

| PB-5 | I have sex because it makes me feel good. | 2.81 ± 0.767 | −1.045 | 1.090 |

| PB-6 | I have sex because it makes me feel loved. | 2.69 ± 0.791 | −0.666 | 0.157 |

| PB-7 | I have sex because I want to hang out with my friends. | 1.48 ± 0.755 | 1.592 | 2.059 |

| PB-8 | I have sex because I want to know what it feels like to have sex. | 2.17 ± 0.942 | 0.000 | −1.304 |

| PB-9 | I have sex because it makes me feel confident about myself. | 1.96 ± 0.875 | 0.329 | −1.046 |

| PB-10 | I have sex because I think it is a wonderful thing that people I admire do. | 1.46 ± 0.633 | 1.043 | 0.027 |

| Total | 1.91 ± 0.505 | |||

| Item | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| Perceived cost (n = 119) for those who have not had a sexual experience | |||

| 1 (PC-5) | I do not have sex because my friends around me do not agree to have sex with me. | 0.776 | |

| 2 (PC-9) | I do not have sex because I feel guilty about having sex. | 0.773 | |

| 3 (PC-3) | I do not have sex because my parents do not allow it. | 0.740 | |

| 4 (PC-1) | I do not have sex because I think it is morally wrong or against my religious beliefs. | 0.681 | |

| 5 (PC-8) | I do not have sex because having sex does not make me happy. | 0.472 | |

| 6 (PC-10) | I do not have sex because my or my partner’s unwanted pregnancy could ruin my future life. | 0.758 | |

| 7 (PC-6) | I do not have sex because me or my partner may become pregnant. | 0.729 | |

| 8 (PC-4) | I do not have sex because I do not consider myself mature enough to do so. | 0.590 | |

| 9 (PC-2) | I do not have sex because it puts me at risk of contracting a sexually transmitted disease or AIDS. | 0.548 | |

| 10 (PC-7) | I do not have sex because I have not met someone I truly love. | 0.431 | |

| Eigenvalue | 4.706 | 1.399 | |

| Total variance explained proportion (%) | 47.056 | 13.990 | |

| Cumulative proportion (%) | 47.056 | 61.045 | |

| Perceived benefits (n = 108) for those who had a sexual experience | |||

| 11 (PB-7) | I have sex because I want to hang out with my friends. | 0.805 | |

| 12 (PB-10) | I have sex because I think it is a wonderful thing that people I admire do. | 0.765 | |

| 13 (PB-3) | I have sex because I want to become pregnant or become a parent. | 0.644 | |

| 14 (PB-1) | I have sex because it helps me forget the problems I am facing. | 0.629 | |

| 15 (PB-2) | I have sex because it makes me feel like an adult. | 0.625 | |

| 16 (PB-4) | I have sex to have or make friends of the opposite sex. | 0.515 | |

| 17 (PB-5) | I have sex because it makes me feel good. | 0.709 | |

| 18 (PB-6) | I have sex because it makes me feel loved. | 0.615 | |

| 19 (PB-9) | I have sex because it makes me feel confident about myself. | 0.517 | |

| 20 (PB-8) | I have sex because I want to know what it feels like to have sex. | 0.417 | |

| Eigenvalue | 4.256 | 1.562 | |

| Total variance explained proportion (%) | 42.562 | 15.615 | |

| Cumulative proportion (%) | 42.562 | 58.177 | |

| Model | χ2 | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | <3 | ≤08 | >0.90 | |

| Results for Perceived Cost | 71.653 (df = 34, p < 0.001) | 2.107 | 0.097 (90% CI: 0.07–0.13) | 0.924 |

| Results for Perceived Benefits | 69.396 (df = 34, p < 0.001) | 2.041 | 0.099 (90% CI: 0.07–0.13) | 0.901 |

| Characteristics | Categories | Perceived Cost (n = 119) for Those Who Have Not Had a Sexual Experience | Perceived Benefits (n = 108) For Those Who Had a Sexual Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | t or F(p) | Mean ± SD | t or F(p) | ||

| Gender | Female | 2.27 ± 0.637 | 2.725 (0.007) ** | 1.76 ± 0.508 | 3.421 (0.001) ** |

| Male | 1.97 ± 0.550 | 2.08 ± 0.448 | |||

| Sexual tolerance | Conservative | 2.41 ± 0.805 a | 5.116 (0.007) ** | 1.79 ± 0.652 | 0.494 (0.611) |

| Moderate | 2.07 ± 0.491 b | 1.93 ± 04.68 | |||

| Open | 1.89 ± 0.515 b,c | 1.93 ± 0.511 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, H.-J.; Lee, J.; Nam, S.-H. Psychometric Evaluation of the Korean Version of the Perceived Costs and Benefits Scale for Sexual Intercourse. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152166

Jang H-J, Lee J, Nam S-H. Psychometric Evaluation of the Korean Version of the Perceived Costs and Benefits Scale for Sexual Intercourse. Healthcare. 2023; 11(15):2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152166

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Hee-Jung, Jungmin Lee, and Soo-Hyun Nam. 2023. "Psychometric Evaluation of the Korean Version of the Perceived Costs and Benefits Scale for Sexual Intercourse" Healthcare 11, no. 15: 2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152166

APA StyleJang, H.-J., Lee, J., & Nam, S.-H. (2023). Psychometric Evaluation of the Korean Version of the Perceived Costs and Benefits Scale for Sexual Intercourse. Healthcare, 11(15), 2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152166