Awareness and Practices towards Vaccinating Their Children against COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study among Pakistani Parents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting and Procedures

2.2. Study Instrument

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval

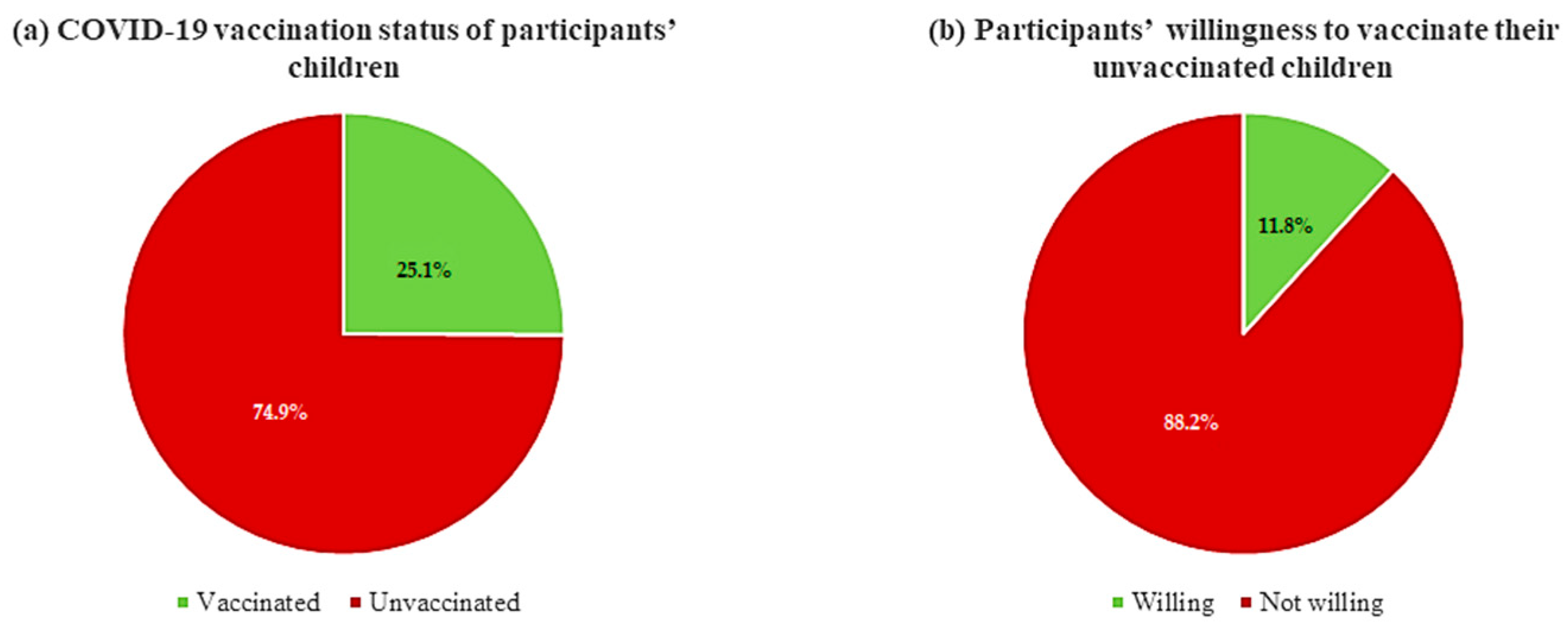

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guan, W.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.H.; Ou, C.Q.; He, J.X.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.L.; Hui, D.S.; et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Indian J. Pediatr. 2020, 87, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.C.; Chen, C.S.; Chan, Y.J. The outbreak of COVID-19: An overview. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2020, 83, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. Available online: https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Gonzalez-Dambrauskas, S.; Vasquez-Hoyos, P.; Camporesi, A.; Cantillano, E.M.; Dallefeld, S.; Dominguez-Rojas, J.; Francoeur, C.; Gurbanov, A.; Mazzillo-Vega, L.; Shein, S.L.; et al. Paediatric critical COVID-19 and mortality in a multinational prospective cohort. Lancet Reg. Health–Am. 2022, 12, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, K.; Haque, M.; Nusrat, N.; Adnan, N.; Islam, S.; Lutfor, A.B.; Begum, D.; Rabbany, A.; Karim, E.; Malek, A.; et al. Management of Children Admitted to Hospitals across Bangladesh with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 and the Implications for the Future: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Haque, M.; Shetty, A.; Choudhary, S.; Bhatt, R.; Sinha, V.; Manohar, B.; Chowdhury, K.; Nusrat, N.; Jahan, N.; et al. Characteristics and Management of Children With Suspected COVID-19 Admitted to Hospitals in India: Implications for Future Care. Cureus 2022, 14, e27230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Raza, M.; Junejo, S.; Maqsood, S. Clinical features and outcome of COVID-19 positive children from a tertiary healthcare hospital in Karachi. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 5988–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, O.; Muttalib, F.; Tang, K.; Jiang, L.; Lassi, Z.S.; Bhutta, Z. Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes of paediatric COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Khan, T.M.; Shehzadi, N.; Hussain, K. How prepared was Pakistan for the COVID-19 outbreak? Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 14, e44–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, K.; Shafiq, S.; Raees, I.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Salman, M.; Khan, A.H.; Meyer, J.C.; Godman, B. Co-infections, secondary infections, and antimicrobial use in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during the first five waves of the pandemic in Pakistan; findings and implications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Command and Operations Centers (NCOC). COVID-19 Situation. Available online: https://covid.gov.pk/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Ahmed, T.; Ilyas, M.; Yousafzai, W. COVID-19 in Children Rattles Healthcare-Hospitals in Three Major Cities Suspect Higher Number of Coronavirus Cases in Minors. 2021. Available online: https://tribune.com.pk/story/2293275/covid-19-in-children-rattles-healthcare (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- The Express Tribune. At Least 5792 Children Tested Positive for COVID-19 in Islamabad. 2021. Available online: https://tribune.com.pk/story/2292667/at-least-5792-children-tested-positive-for-covid-19-in-islamabad (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Khan, A.H.; Harun, S.N.; Salman, M.; Godman, B. Antibiotic overprescribing among neonates and children hospitalized with COVID-19 in Pakistan and the implications. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horby, P.W.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Emberson, J.; Palfreeman, A.; Raw, J.; Elmahi, E.; Prudon, B.; et al. Lopinavir-ritonavir in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recovery Collaborative Group; Horby, P.; Mafham, M.; Linsell, L.; Bell, J.L.; Staplin, N.; Emberson, J.R.; Wiselka, M.; Ustianowski, A.; Elmahi, E.; et al. Effect of Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2030–2040. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, O. COVID-19: Remdesivir has little or no impact on survival, WHO trial shows. BMJ 2020, 371, m4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, Y.M.; Burela, P.A.; Pasupuleti, V.; Piscoya, A.; Vidal, J.E.; Hernandez, A.V. Ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolino, M.S.; Meira, K.C.; Guimarães, N.S.; Motta, P.P.; Chagas, V.S.; Kelles, S.M.B.; de Sá, L.C.; Valacio, R.A.; Ziegelmann, P.K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19: Evidence beyond the hype. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, F.; Kodjamanova, P.; Chen, X.; Li, N.; Atanasov, P.; Bennetts, L.; Patterson, B.J.; Yektashenas, B.; Mesa-Frias, M.; Tronczynski, K.; et al. Economic Burden of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Clin. Outcomes Res. 2022, 14, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoye, F.; Gebrye, T.; Arije, O.; Fatoye, C.T.; Onigbinde, O.; Mbada, C. Economic Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on households. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 40, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I.; Nauman, A.; Paul, P.; Ganesan, S.; Chen, K.-H.; Jalil, S.M.S.; Jaouni, S.H.; Kawas, H.; Khan, W.A.; Vattoth, A.L.; et al. The efficacy and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines in reducing infection, severity, hospitalization, and mortality: A systematic review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2027160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korang, S.K.; von Rohden, E.; Veroniki, A.A.; Ong, G.; Ngalamika, O.; Siddiqui, F.; Juul, S.; Nielsen, E.E.; Feinberg, J.B.; Petersen, J.J.; et al. Vaccines to prevent COVID-19: A living systematic review with Trial Sequential Analysis and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0260733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Westwood, D.; MacFadden, D.R.; Soucy, J.-P.R.; Daneman, N. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: A living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Soucy, J.-P.R.; Westwood, D.; Daneman, N.; MacFadden, D.R. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: Rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lshaikh, F.S.; Godman, B.; Sindi, O.N.; Seaton, R.A.; Kurdi, A. Prevalence of bacterial coinfection and patterns of antibiotics prescribing in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272375. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Saleem, M.S.; Ikram, M.N.; Salman, M.; Butt, S.A.; Khan, S.; Godman, B.; Seaton, R.A. Co-infections and antimicrobial use among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Punjab, Pakistan: Findings from a multicenter, point prevalence survey. Pathog. Glob. Health 2022, 116, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Salman, M.; Yasir, M.; Godman, B.; Majeed, H.A.; Kanwal, M.; Iqbal, M.; Riaz, M.B.; Hayat, K.; Hasan, S.S. Antibiotic consumption among hospitalized neonates and children in Punjab province, Pakistan. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J. How COVID-19 is accelerating the threat of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ 2020, 369, m1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.; Jeong, S.; Lee, N.; Park, M.-J.; Song, W.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.-S. Impact of COVID-19 on Antimicrobial Consumption and Spread of Multidrug-Resistance in Bacterial Infections. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daria, S.; Islam, M.R. Indiscriminate Use of Antibiotics for COVID-19 Treatment in South Asian Countries is a Threat for Future Pandemics Due to Antibiotic Resistance. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 15, 2632010x221099889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, U. The cost of antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voice of America. Pakistan Starts COVID-19 Inoculation. Available online: https://www.voanews.com/COVID-19-pandemic/pakistan-starts-COVID-19-inoculation-drive (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Aljazeera. Pakistan Kicks Off COVID Vaccination Drive for Senior Citizens. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/10/pakistan-kicks-off-senior-citizen-coronavirus-vaccinations (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Siddiqui, A.; Ahmed, A.; Tanveer, M.; Saqlain, M.; Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S. An overview of procurement, pricing, and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines in Pakistan. Vaccine 2021, 39, 5251–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawn. Pakistan Rolls out COVID Jabs for Children Aged 5 to 11. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1710866 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Bolo. COVID-19 Vaccination Guidelines for Children in Pakistan. 2022. Available online: https://www.bolo-pk.info/hc/en-us/articles/4417496845847-COVID-19-Vaccination-Guidelines-for-Children-in-Pakistan (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- National Command and Operation Center (NCOC). Important Guidelines. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/media/3631/file/Annual%20Report%202020.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Al-Qerem, W.; Al Bawab, A.Q.; Hammad, A.; Jaber, T.; Khdair, S.; Kalloush, H.; Ling, J.; Mosleh, R. Parents’ attitudes, knowledge and practice towards vaccinating their children against COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2044257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solís Arce, J.S.; Warren, S.S.; Meriggi, N.F.; Scacco, A.; McMurry, N.; Voors, M.; Syunyaev, G.; Malik, A.A.; Aboutajdine, S.; Adeojo, O.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low-and middle-income countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif Nia, H.; Allen, K.A.; Arslan, G.; Kaur, H.; She, L.; Khoshnavay Fomani, F.; Gorgulu, O.; Sivarajan Froelicher, E. The predictive role of parental attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines and child vulnerability: A multi-country study on the relationship between parental vaccine hesitancy and financial well-being. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1085197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafadar, A.H.; Tekeli, G.G.; Jones, K.A.; Stephan, B.; Dening, T. Determinants for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the general population: A systematic review of reviews. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Leigh, J.P.; Hu, J.; El-Mohandes, A. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, C.S.B.; Singh, R.G.; Yao, L. Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation on Social Media Virality: Content Analysis of Message Themes and Writing Strategies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e37806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muric, G.; Wu, Y.; Ferrara, E. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy on Social Media: Building a Public Twitter Data Set of Antivaccine Content, Vaccine Misinformation, and Conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e30642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Meyer, J.C.; Burnett, R.J.; Campbell, S.M. Mitigating Vaccine Hesitancy and Building Trust to Prevent Future Measles Outbreaks in England. Vaccines 2023, 11, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, O. Measles outbreak in Somali American community follows anti-vaccine talks. BMJ 2017, 357, j2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Child Adolescent H. Vaccine hesitancy: A generation at risk. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019, 3, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.J.; Saqlain, M.; Tariq, W.; Waheed, S.; Tan, S.H.S.; Nasir, S.I.; Ullah, I.; Ahmed, A. Population preferences and attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination: A cross-sectional study from Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Malik, J.; Ishaq, U. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in Pakistan among health care workers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraka, M.A.; Manzoor, M.N.; Ayoub, U.; Aljowaie, R.M.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Zaidi, S.T.R.; Salman, M.; Kow, C.S.; Aldeyab, M.A.; Hasan, S.S. Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Punjab, Pakistan. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Bashir, S.; Shahid, A.; Raees, I.; Salman, M.; Merchant, H.A.; Aldeyab, M.A.; Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinics in Pakistan: A Multicentric, Prospective, Survey-Based Study. Viruses 2022, 14, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, Z.; Maryam, I.; Munir, M.; Salman, M.; Baraka, M.A.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Khan, Y.H.; Mallhi, T.H.; Hasan, S.S.; Meyer, J.C.; et al. Covid-19 vaccines status, acceptance and hesitancy among maintenance hemodialysis patients: A cross-sectional study and the implications for Pakistan and beyond. Vaccines 2023, 11, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qerem, W.; Jarab, A.; Hammad, A.; Alasmari, F.; Ling, J.; Alsajri, A.H.; Al-Hishma, S.W.; Abu Heshmeh, S.R. Iraqi parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards vaccinating their children: A cross-sectional study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.; Axfors, C.; Contopoulos-Ioannidis, D.G. Population-level COVID-19 mortality risk for non-elderly individuals overall and for non-elderly individuals without underlying diseases in pandemic epicenters. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Child Mortality and COVID-19. March 2023. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/covid-19/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 10 Reasons Your Child Should Get Vaccinated for COVID-19 as Soon as Possible. Available online: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2021/10-reasons-your-child-should-get-vaccinated-for-covid-19-as-soon-as-possible (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Collignon, P.; Beggs, J.J.; Walsh, T.R.; Gandra, S.; Laxminarayan, R. Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: A univariate and multivariable analysis. Lancet Planet Health 2018, 2, e398–e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godman, B.; Haque, M.; McKimm, J.; Abu Bakar, M.; Sneddon, J.; Wale, J.; Campbell, S.; Martin, A.P.; Hoxha, I.; Abilova, V.; et al. Ongoing strategies to improve the management of upper respiratory tract infections and reduce inappropriate antibiotic use particularly among lower and middle-income countries: Findings and implications for the future. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2019, 36, 301–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Z.; Hassali, M.A.; Godman, B.; Fatima, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Sajid, A.; Rehman, I.U.; Nadeem, M.U.; Javaid, Z.; Malik, M.; et al. Sale of WHO AWaRe groups antibiotics without a prescription in Pakistan: A simulated client study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulis, G.; Sayood, S.; Katukoori, S.; Bollam, N.; George, I.; Yaeger, L.H.; Saeed, A.; Usman, Q.M.; Amir, A.; Pulcini, C.; et al. Exposure to World Health Organization’s AWaRe antibiotics and isolation of multidrug resistant bacteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Z.; Godman, B.; Azhar, F.; Kalungia, A.C.; Fadare, J.; Opanga, S.; Markovic-Pekovic, V.; Hoxha, I.; Saeed, A.; Al-Gethamy, M.; et al. Progress on the national action plan of Pakistan on antimicrobial resistance (AMR): A narrative review and the implications. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqlain, M.; Ahmed, A.; Nabi, I.; Gulzar, A.; Naz, S.; Munir, M.M.; Ahmed, Z.; Kamran, S. Public knowledge and practices regarding coronavirus disease 2019: A cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 629015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Asif, N.; Zaidi, H.A.; Hussain, K.; Shehzadi, N.; Khan, T.M.; Saleem, Z. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practices related to COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in two Pakistani university populations. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2020, 36, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, K.; Rubab, Z.-E.; Umar, M.; Rehman, R.; Baig, M.; Baig, F. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices against the growing threat of COVID-19 among medical students of Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Mustafa, Z.; Asif, N.; Zaidi, H.A.; Shehzadi, N.; Khan, T.M.; Saleem, Z.; Hussain, K. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practices related to COVID-19 among health professionals of Punjab province of Pakistan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.; Jawed, S.; Ali, R.; Noreen, K.; Baig, M.; Baig, J. COVID-19 pandemic awareness, attitudes, and practices among the Pakistani general public. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 588537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, H.; Afridi, M.; Akhtar, S.; Ahmad, H.; Ali, S.; Khalid, S.; Awan, S.M.; Jahangiri, S.; Khader, Y.S. Pakistan’s response to COVID-19: Overcoming national and international hypes to fight the pandemic. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e28517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabra, H.K.; Bakr, M.A.; Rageh, O.E.; Khaled, A.; Elbakliesh, O.M.; Kabbash, I.A. Parents’ perception of COVID-19 risk of infection and intention to vaccinate their children. Vacunas 2023, 24, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatatbeh, M.; Albalas, S.; Khatatbeh, H.; Momani, W.; Melhem, O.; Al Omari, O.; Tarhini, Z.; A’aqoulah, A.; Al-Jubouri, M.; Nashwan, A.J.; et al. Children’s rates of COVID-19 vaccination as reported by parents, vaccine hesitancy, and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children: A multi-country study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Zhong, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Li, W.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, X.; et al. Factors influencing parents’ willingness to vaccinate their preschool children against COVID-19: Results from the mixed-method study in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2090776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitro, A.; Sirikul, W.; Dilokkhamaruk, E.; Sumitmoh, G.; Pasirayut, S.; Wongcharoen, A.; Panumasvivat, J.; Ongprasert, K.; Sapbamrer, R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and influential factors among Thai parents and guardians to vaccinate their children. Vaccine X 2022, 11, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechotta, V.; Siemens, W.; Thielemann, I.; Toews, M.; Koch, J.; Vygen-Bonnet, S.; Kothari, K.; Grummich, K.; Braun, C.; Kapp, P.; et al. Safety and effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19 in children aged 5–11 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2023, 7, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, A.; Kani, R.; Iwagami, M.; Takagi, H.; Yasuhara, J.; Kuno, T. Assessment of efficacy and safety of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in children aged 5 to 11 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.; Pandey, V.; Kumar, A.; Gangadevi, P.; Goel, A.D.; Joseph, J.; Kurien, N. Acceptance and attitude of parents regarding COVID-19 vaccine for children: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2022, 14, e24518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.-L.; Gan, G.-G.; Chai, C.-S.; Anuar, N.A.B.; Sindeh, W.; Chua, W.-J.; Said, A.B.; Tan, S.-B. The willingness of parents to vaccinate their children younger than 12 years against COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, M.; Sahin, M.K. Parents’ willingness and attitudes concerning the COVID-19 vaccine: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Subgroups | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <40 | 123 (27.3) |

| 40–49 | 195 (43.2) | |

| ≥50 | 133 (29.5) | |

| Sex | Male | 147 (32.6) |

| Female | 304 (67.4) | |

| Education | Illiterate | 32 (7.1) |

| Religious education only | 18 (4.0) | |

| Primary | 150 (33.3) | |

| Secondary | 195 (43.2) | |

| Higher secondary or above | 56 (12.4) | |

| Income (PKR) | <30,000 | 29 (6.4) |

| 31,000–60,000 | 311 (69.0) | |

| >60,000 | 111 (24.6) | |

| Smoking status | Smoker | 51 (11.3) |

| Non-smoker | 400 (88.7) | |

| Working or studying in a medical field | Yes | 21 (4.7) |

| No | 430 (95.3) | |

| Any chronic disease | Yes | 67 (14.9) |

| No | 384 (85.1) | |

| COVID-19 Immunization status | Fully immunized | 327 (72.5) |

| Partially immunized | 67 (14.9) | |

| Unvaccinated | 57 (12.6) | |

| Willing to take COVID-19 vaccine (Currently unvaccinated—N = 57) | Yes | 18 (31.6) |

| No | 27 (47.4) | |

| Maybe | 12 (21.1) | |

| No. of children | 1 | 23 (5.1) |

| 2 | 166 (36.8) | |

| 3 | 215 (47.7) | |

| 4 or more | 47 (10.4) | |

| Do you have any preterm children? | Yes | 50 (11.1) |

| No | 401 (88.9) | |

| Do any of your children suffer from a chronic illness or taking steroids or immunosuppressant medications? | Yes | 39 (8.6) |

| No | 412 (91.4) | |

| Do you know somebody close to you that was infected with COVID-19? | Yes | 451 (100.0) |

| No | -- | |

| Have you been infected with COVID-19 during the pandemic? | Yes | 105 (23.3) |

| No | 334 (74.1) | |

| Maybe | 12 (2.7) | |

| Has any of your children ever been infected with COVID-19? | Yes | 10 (2.2) |

| No | 422 (93.6) | |

| Maybe | 19 (4.2) |

| Variable | Sub-Groups | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated seriousness of COVID-19 on participants | Low risk | 382 (84.7) |

| High risk | 69 (15.3) | |

| What is the likelihood that you will be infected with COVID-19 during the next 6 months? | I think that I will be infected and my symptoms will be severe | 32 (7.1) |

| I think that I will be infected and my symptoms will be mild | 67 (14.9) | |

| I do not think that I will be infected | 93 (20.6) | |

| I do not know | 259 (57.4) | |

| Estimated seriousness of COVID-19 on children | Low risk | 243 (53.9) |

| High risk | 208 (46.1) | |

| What is the likelihood that your children will be infected with COVID-19 during the next 6 months? | I think my child will be infected and my symptoms will be severe | 191 (42.4) |

| I think my child will be infected and my symptoms will be mild | 66 (14.6) | |

| I do not think my child will be infected | 89 (19.7) | |

| I do not know | 105 (23.3) |

| Items | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | |

| Signs and symptoms | ||

| Fever | 325 (72.1) | 126 (27.9) |

| Chills | 211 (46.8) | 240 (53.2) |

| Cough | 147 (32.6) | 304 (67.4) |

| Diarrhea | 308 (68.3) | 143 (31.7) |

| Middle ear infection | 221 (49.0) | 230 (51.0) |

| Loss of smell and taste | 278 (61.6) | 173 (38.4) |

| No symptoms | 428 (94.9) | 23 (5.1) |

| Transmission | ||

| Drinking unclean water | 270 (59.9) | 181 (40.1) |

| Eating unclean food | 277 (61.4) | 174 (38.6) |

| Inhalation of respiratory droplets | 231 (51.2) | 220 (48.8) |

| Eating or touching wild animals | 175 (38.8) | 276 (61.2) |

| Preventive measures | ||

| Washing hands with regular soap | 401 (88.9) | 50 (11.1) |

| Using detergents | 262 (58.1) | 189 (41.9) |

| Social distancing | 372 (82.5) | 79 (17.5) |

| Avoid touching face/mouth/nose/eyes | 266 (59.0) | 185 (41.0) |

| Avoid eating meat | 355 (78.7) | 96 (21.3) |

| Consuming herbs | 371 (82.3) | 80 (17.7) |

| Is there a drug in pharmacies or medical stores that can cure COVID-19? | 190 (42.1) | 261 (57.9) |

| Vaccine-related knowledge | ||

| Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine in children | 155 (34.4) | 296 (65.6) |

| Safety of COVID-19 vaccine in children | 196 (43.5) | 255 (56.5) |

| COVID-19 vaccine administration | 378 (83.8) | 73 (16.2) |

| Preventive Practices | N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almost Always | Most of the Time | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | |

| Wearing face masks when in public | -- | 451 (100.0) | -- | -- | -- |

| Washing hands with soap | -- | 394 (87.4) | 43 (9.5) | 13 (2.9) | 1 (0.2) |

| Using detergents | -- | 388 (86.0) | 54 (12.0) | 9 (2.0) | -- |

| Social distancing | -- | 419 (92.9) | 29 (6.4) | 3 (0.7) | -- |

| Avoid touching face/mouth/nose/eyes with contaminated/unclean hands | -- | 421 (93.3) | 25 (5.5) | 5 (1.1) | -- |

| Variable | Subgroups | Intention to Vaccinate 5–18 Years Old Children for COVID-19 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing | Not Willing | |||

| Age (years) | <40 | 10 (25.0) | 81 (27.2) | 0.930 |

| 40–49 | 17 (42.5) | 128 (43.0) | ||

| ≥50 | 13 (32.5) | 89 (29.9) | ||

| Gender | Male | 27 (67.5) | 193 (64.8) | 0.860 |

| Female | 13 (32.5) | 105 (35.2) | ||

| Education | No formal education | 0 (0.0) | 46 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 5 (12.5) | 131 (44.0) | ||

| Secondary or above | 35 (87.5) | 121 (40.6)) | ||

| Income | <30,000 PKR | 3 (7.5) | 19 (6.4) | 0.076 |

| 31,000–60,000 PKR | 23 (57.5) | 220 (73.8) | ||

| >60,000 PKR | 14 (35.0) | 59 (19.8) | ||

| Smoking status | Smoker | 7 (17.5) | 30 (10.1) | 0.175 |

| Non smoker | 33 (82.5) | 268 (89.9) | ||

| Working or studying in a medical field | Yes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.000 |

| No | 40 (100.0) | 297 (99.7) | ||

| COVID-19 Immunization status | Fully immunized | 30 (75.0) | 217 (72.8) | 0.051 |

| Partially immunized | 9 (22.5) | 39 (13.1) | ||

| Unvaccinated | 1 (2.5) | 42 (14.1) | ||

| Any chronic disease | Yes | 6 (15.0) | 44 (14.8) | 1.000 |

| No | 34 (85.0) | 254 (85.2) | ||

| Do you have any preterm children? | Yes | 2 (5.0) | 31 (10.4) | 0.399 |

| No | 38 (95.0) | 267 (89.6) | ||

| Do any of your children suffer from a chronic illness or taking steroids or immunosuppressant’s medications? | Yes | 7 (17.5) | 21 (7.0) | 0.034 |

| No | 33 (82.5) | 277 (93.0) | ||

| Have you ever been infected with COVID-19? | Yes (confirmed/suspected) | 2 (5.0) | 31 (10.4) | 0.399 |

| No | 38 (95.0) | 267 (89.6) | ||

| Has any of your children ever been infected with COVID-19? | Yes (confirmed/suspected) | 7 (17.5) | 21 (7.0) | 0.034 |

| No | 33 (82.5) | 277 (93.0) | ||

| Estimated seriousness of COVID-19 on participants | Low risk | 34 (85.0) | 266 (89.3) | 0.425 |

| High risk | 6 (15.0) | 32 (10.7) | ||

| What is the likelihood that you will be infected with COVID-19 during the next 6 months? | I think that I will be infected | 13 (32.5) | 66 (22.1) | 0.275 |

| I do not think that I will be infected | 9 (22.5) | 62 (20.8) | ||

| I do not know | 18 (45.0) | 170 (57.0) | ||

| Estimated seriousness of COVID-19 on children | Low risk | 19 (47.5) | 162 (54.4) | 0.500 |

| High risk | 21 (52.5) | 136 (45.6) | ||

| What is the likelihood that your children will be infected with COVID-19 during the next 6 months? | I think my child will get infected | 24 (60.0) | 168 (56.4) | 0.356 |

| I do not think my child will be infected | 5 (12.5) | 65 (21.8) | ||

| I do not know | 11 (27.5) | 65 (21.8) | ||

| Knowledge of COVID-19 and its vaccines | -- | 212.66 | 163.71 | 0.003 |

| Preventive practice related to COVID-19 | -- | 163.44 | 170.31 | 0.614 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harmain, Z.U.; Alkubaisi, N.A.; Hasnain, M.; Salman, M.; Baraka, M.A.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Khan, Y.H.; Mallhi, T.H.; Meyer, J.C.; Godman, B. Awareness and Practices towards Vaccinating Their Children against COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study among Pakistani Parents. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2378. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172378

Harmain ZU, Alkubaisi NA, Hasnain M, Salman M, Baraka MA, Mustafa ZU, Khan YH, Mallhi TH, Meyer JC, Godman B. Awareness and Practices towards Vaccinating Their Children against COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study among Pakistani Parents. Healthcare. 2023; 11(17):2378. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172378

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarmain, Zain Ul, Noorah A. Alkubaisi, Muhammad Hasnain, Muhammad Salman, Mohamed A. Baraka, Zia Ul Mustafa, Yusra Habib Khan, Tauqeer Hussain Mallhi, Johanna C. Meyer, and Brian Godman. 2023. "Awareness and Practices towards Vaccinating Their Children against COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study among Pakistani Parents" Healthcare 11, no. 17: 2378. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172378

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)