Examining Saudi Physicians’ Approaches to Communicate Bad News and Bridging Generational Gaps

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Sample Size and Study Population

2.3. Assessment of the Study Outcome

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethical Approval

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data

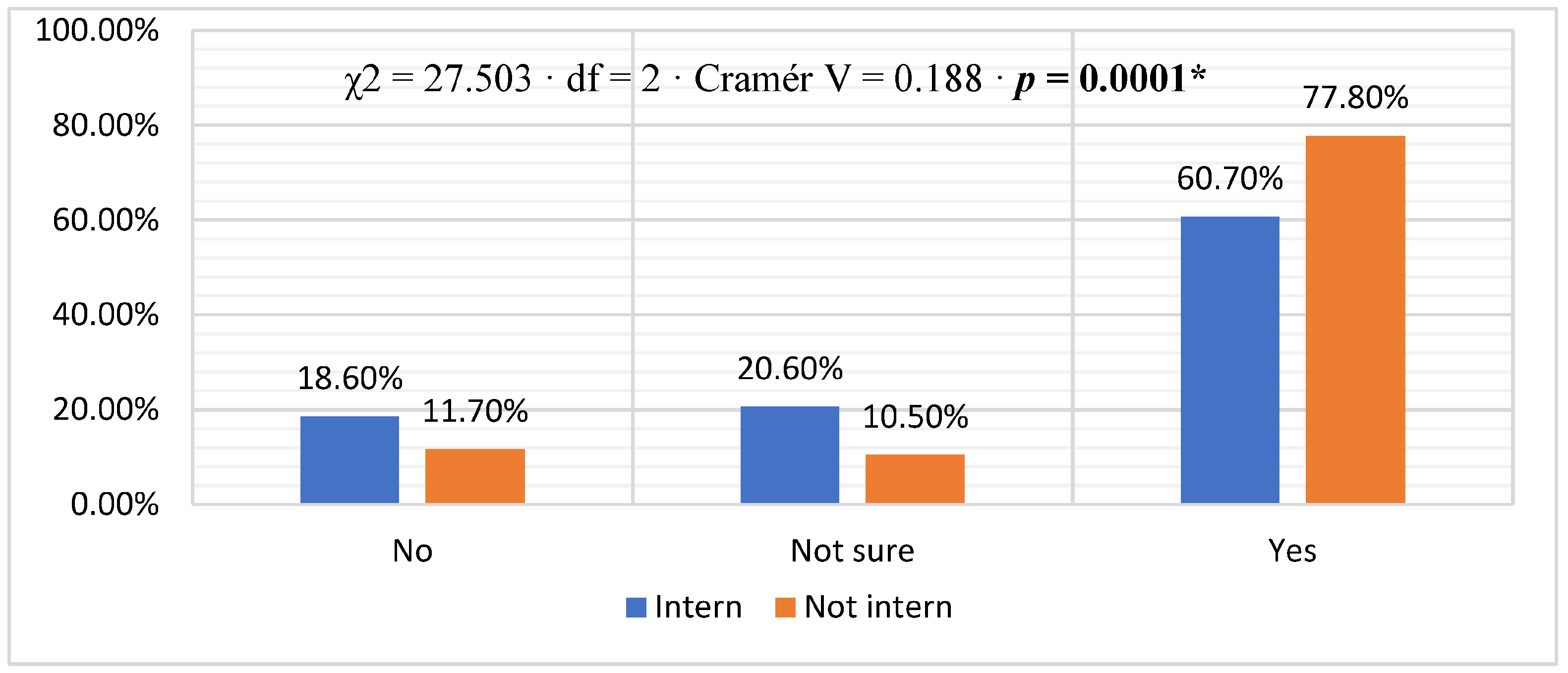

3.2. Comfort Level in Discussing Bad News with Patients or Their Relatives

3.3. The Communication Practices of Healthcare Providers When Break Bad News

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, J.; Shim, R. Perceptions of health care communication: Examining the role of patients’ psychological distress. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2010, 102, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.F.; Longnecker, N. Doctor-patient communication: A review. Ochsner J. 2010, 10, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DeRouen, M.C.; Smith, A.W.; Tao, L.; Bellizzi, K.M.; Lynch, C.F.; Parsons, H.M.; Kent, E.E.; Keegan, T.H.; Group, A.H.S.C. Cancer-related information needs and cancer’s impact on control over life influence health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckjord, E.B.; Arora, N.K.; McLaughlin, W.; Oakley-Girvan, I.; Hamilton, A.S.; Hesse, B.W. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: Implications for cancer care. J. Cancer Surviv. 2008, 2, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckman, R. Breaking bad news: Why is it still so difficult? Br. Med. J. 1984, 288, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Fallowfield, L.; Lewis, S. Can oncologists detect distress in their out-patients and how satisfied are they with their performance during bad news consultations? Br. J. Cancer 1994, 70, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazari, P.; Taleghani, F.; Hematti, S.; Malekian, A.; Mokarian, F.; Hakimian, S.M.R.; Ehsani, M. Breaking bad news protocol for cancer disclosure: An Iranian version. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 2017, 10, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Rozveh, A.K.; Amjad, R.N.; Rozveh, J.K.; Rasouli, D. Attitudes toward telling the truth to cancer patients in Iran: A review article. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Res. 2017, 11, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Zolkefli, Y. The Ethics of Truth-Telling in Health-Care Settings. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L.; Giraldi, T.; Messina, E.G.; Magnani, K.; Valle, E.; Cartei, G. Physicians’ attitudes to and problems with truth-telling to cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2000, 8, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, S.; Mehdorn, H.M. Breaking bad news to patients with intracranial tumors: The patients’ perspective. World Neurosurg. 2018, 118, e254–e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morasso, G.; Alberisio, A.; Capelli, M.; Rossi, C.; Baracco, G.; Costantini, M. Illness awareness in cancer patients: A conceptual framework and a preliminary classification hypothesis. Psycho-Oncology 1997, 6, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, A.; Busato, C.; Annunziata, M.; Magri, M.; Foladore, S.; Zanon, M.; Tumolo, S.; Monfardini, S. Prospective analysis of the information level of Italian cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 1995, 31, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Fossati, R.; Talamini, R.; Parazzini, F.; Confalonieri, C.; Marsoni, S.; Torri, W.; Tognoni, G.; Gosso, P.; Tagliati, D. What doctors tell patients with breast cancer about diagnosis and treatment: Findings from a study in general hospitals. Br. J. Cancer 1986, 54, 319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Surbone, A. Truth telling to the patient. JAMA 1992, 268, 1661–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arraras, J.I.; Illarramendi, J.J.; Valerdi, J.J.; Wright, S.J. Truth-telling to the patient in advanced cancer: Family information filtering and prospects for change. Psycho-Oncology 1995, 4, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.R.; Paci, E. Disclosure practices and cultural narratives: Understanding concealment and silence around cancer in Tuscany, Italy. Social. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 1433–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, M.; Kellett, J.; Lewis, E.; Brabrand, M.; Ní Chróinín, D. Truth disclosure on prognosis: Is it ethical not to communicate personalised risk of death? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 72, e13222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zulueta, P. Truth, trust and the doctor–patient relationship. In Primary Care Ethics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Craxì, L.; Di Marco, V. Breaking bad news: How to cope. Dig. Liver Dis. 2018, 50, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallowfield, L.; Jenkins, V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet 2004, 363, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, A.; Sanson-Fisher, R.W. Breaking bad news: Consensus guidelines for medical practitioners. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995, 13, 2449–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baile, W.F.; Buckman, R.; Lenzi, R.; Glober, G.; Beale, E.A.; Kudelka, A.P. SPIKES—A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer. Oncologist 2000, 5, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifart, C.; Hofmann, M.; Bär, T.; Riera Knorrenschild, J.; Seifart, U.; Rief, W. Breaking bad news-what patients want and what they get: Evaluating the SPIKES protocol in Germany. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.R.; Yi, S.Y. Delivering bad news to a patient: A survey of residents and fellows on attitude and awareness. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2013, 25, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira da Silveira, F.J.; Botelho, C.C.; Valadão, C.C. Breaking bad news: Doctors’ skills in communicating with patients. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2017, 135, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafallah, M.A.; Ragab, E.A.; Salih, M.H.; Osman, W.N.; Mohammed, R.O.; Osman, M.; Taha, M.H.; Ahmed, M.H. Breaking bad news: Awareness and practice among Sudanese doctors. AIMS Public. Health 2020, 7, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, P.B.; Abayomi, O.; Johnson, P.O.; Oloyede, T.; Oyelekan, A.A. Breaking bad news in clinical setting-health professionals’ experience and perceived competence in southwestern Nigeria: A cross sectional study. Ann. Afr. Med. 2013, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyce, W. On breaking bad news. JAMA 2018, 320, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, N.M.; Watson, J.S.; Langelier, N.A.; Atkinson, R.E.; Ying, G.-S.; Pan, W.; Palladino, V.; Russell, C.; Lin, V.; Tapino, P.J. Breaking Bad: An Assessment of Ophthalmologists’ Interpersonal Skills and Training on Delivering Bad News. J. Acad. Ophthalmol. 2018, 10, e83–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younge, D.; Moreau, P.; Ezzat, A.; Gray, A. Communicating with Cancer Patients in Saudi Arabia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997, 809, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedikian, A.Y.; Saleh, V.; Ibrahim, S. Saudi patient and companion attitudes toward cancer. Ann. Saudi Med. 1985, 5, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, A.M. Cancer patients’ desire for information: A study in a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2009, 15, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljubran, A.H. The attitude towards disclosure of bad news to cancer patients in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2010, 30, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbermann, M.; Hassan, E.A. Cultural perspectives in cancer care: Impact of Islamic traditions and practices in Middle Eastern countries. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2011, 33 (Suppl. S2), S81–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cabrera, M.; Ortega-Martínez, A.R.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Frías-Osuna, A. Design and validation of a questionnaire on communicating bad news in nursing: A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liénard, A.; Merckaert, I.; Libert, Y.; Bragard, I.; Delvaux, N.; Etienne, A.M.; Marchal, S.; Meunier, J.; Reynaert, C.; Slachmuylder, J.L.; et al. Is it possible to improve residents breaking bad news skills? A randomised study assessing the efficacy of a communication skills training program. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berney, A.; Carrard, V.; Schmid Mast, M.; Bonvin, R.; Stiefel, F.; Bourquin, C. Individual training at the undergraduate level to promote competence in breaking bad news in oncology. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 2232–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, G.; Orri, M.; Winterman, S.; Brugière, C.; Verneuil, L.; Revah-Levy, A. Breaking Bad News in Oncology: A Metasynthesis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2437–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monden, K.R.; Gentry, L.; Cox, T.R. Delivering Bad News to Patients. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2016, 29, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biazar, G.; Delpasand, K.; Farzi, F.; Sedighinejad, A.; Mirmansouri, A.; Atrkarroushan, Z. Breaking Bad News: A Valid Concern among Clinicians. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2019, 14, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotłowska, A.; Przeniosło, J.; Sobczak, K.; Plenikowski, J.; Trzciński, M.; Lenkiewicz, O.; Lenkiewicz, J. Influence of Personal Experiences of Medical Students on Their Assessment of Delivering Bad News. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasien, S.; Almuzaini, F. The relationship between empathy and personality traits in Saudi medical students. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, M.E.; Ferguson, K.J.; Lobas, J.G. Teaching medical students and residents skills for delivering bad news: A review of strategies. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques, A.P.; Adkins, E.J.; Knepel, S.; Boulger, C.; Miller, J.; Bahner, D.P. Educating the delivery of bad news in medicine: Preceptorship versus simulation. Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 2011, 1, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, N.C.; Lima, M.G.d.; Brietzke, E.; Mucci, S.; Góis, A.F.T.D. Teaching how to deliver bad news: A systematic review. Rev. Bioética 2019, 27, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables (N = 782) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 384 (49.1%) |

| Male | 398 (50.9%) | |

| Age | 25–30 years | 584 (74.7%) |

| 31–35 years | 78 (10.0%) | |

| 36–40 years | 52 (6.6%) | |

| 41–45 years | 31 (4.0%) | |

| 46–50 years | 28 (3.6%) | |

| Above 51 years | 9 (1.2%) | |

| Marital status | Divorced | 37 (4.7%) |

| Married | 196 (25.1%) | |

| Single | 535 (68.4%) | |

| Widow | 14 (1.8%) | |

| Job title | Consultant | 38 (4.9%) |

| Fellow | 41 (5.2%) | |

| Intern | 354 (45.3%) | |

| Junior Resident | 179 (22.9%) | |

| Registrar | 33 (4.2%) | |

| Senior Resident | 86 (11.0%) | |

| Specialist | 51 (6.5%) | |

| Years of experience | Median [Min, Max] | 1.0 [0, 45] |

| Place of work | Hospitals | 677 (86.6%) |

| PHCCs | 105 (13.4%) |

| Variable | Overall N = 782 | Intern n = 354 | Non-Intern n = 428 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you feel patients should be told everything about them? | No | 101 (12.9%) | 44 (12.4%) | 57 (13.3%) | χ2 = 3.412, df = 2, Cramér V = 0.066, p= 0.182 |

| Not sure | 66 (8.4%) | 37 (10.5%) | 29 (6.8%) | ||

| Yes | 615 (78.6%) | 273 (77.1%) | 342 (79.9%) | ||

| Do you choose a quiet and private place beforehand to communicate bad news? | No | 56 (7.2%) | 24 (6.8%) | 32 (7.5%) | χ2 = 5.631, df = 2, Cramér = 0.085, p = 0.060 |

| Not sure | 64 (8.2%) | 38 (10.7%) | 26 (6.1%) | ||

| Yes | 662 (84.7%) | 292 (82.5%) | 370 (86.4%) | ||

| Do you call the patient by their name? | Always | 568 (72.6%) | 236 (66.7%) | 332 (77.6%) | χ2 = 11.858, df = 2, Cramér V = 0.123, p = 0.003 * |

| Never | 25 (3.2%) | 15 (4.2%) | 10 (2.3%) | ||

| Sometimes | 189 (24.2%) | 103 (29.1%) | 86 (20.1%) | ||

| Do you look at the patient’s face or in the eyes while you talk or listen? | Always | 561 (71.7%) | 252 (71.2%) | 309 (72.2%) | χ2 = 0.109, df = 2 Cramér = 0.012, p = 0.947 |

| Never | 20 (2.6%) | 9 (2.5%) | 11 (2.6%) | ||

| Sometimes | 201 (25.7%) | 93 (26.3%) | 108 (25.2%) | ||

| Before starting the conversation, do you find out what the patient already knows about the news that you are going to communicate? | Always | 440 (56.3%) | 186 (52.5%) | 254 (59.3%) | χ2 = 3.716, df = 2, Cramér = 0.069, p = 0.156 |

| Never | 32 (4.1%) | 15 (4.2%) | 17 (4.0%) | ||

| Sometimes | 310 (39.6%) | 153 (43.2%) | 157 (36.7%) | ||

| To find out what the patient knows and how much they want to know, do you use questions such as, before I talk, do you want to tell me anything or ask me something? | Always | 444 (56.8%) | 190 (53.7%) | 254 (59.3%) | χ2 = 2.733, df = 2, Cramér = 0.059, p = 0.255 |

| Never | 44 (5.6%) | 20 (5.6%) | 24 (5.6%) | ||

| Sometimes | 294 (37.6%) | 144 (40.7%) | 150 (35.0%) | ||

| Before communicating bad news, do you find out in what way the news may affect the patient’s personal, social, or work life? | Always | 439 (56.1%) | 186 (52.5%) | 253 (59.1%) | χ2 = 3.852, df = 2, Cramér = 0.070, p = 0.146 |

| Never | 43 (5.5%) | 19 (5.4%) | 24 (5.6%) | ||

| Sometimes | 300 (38.4%) | 149 (42.1%) | 151 (35.3%) | ||

| In the event that the patient is unsure they wish to be informed, do you give the patient time to consider it? | Always | 523 (66.9%) | 226 (63.8%) | 297 (69.4%) | χ2 = 2.717, df = 2, Cramér = 0.059, p = 0.257 |

| Never | 25 (3.2%) | 12 (3.4%) | 13 (3.0%) | ||

| Sometimes | 234 (29.9%) | 116 (32.8%) | 118 (27.6%) | ||

| Do you keep in mind the opinion of the patient? | Always | 523 (66.9%) | 224 (63.3%) | 299 (69.9%) | χ2 = 5.488, df = 2, Cramér = 0.084, p = 0.064 |

| Never | 35 (4.5%) | 14 (4.0%) | 21 (4.9%) | ||

| Sometimes | 224 (28.6%) | 116 (32.8%) | 108 (25.2%) | ||

| Do you use appropriate language to allow the patient to digest the bad news? | Always | 559 (71.5%) | 248 (70.1%) | 311 (72.7%) | χ2 = 0.660, df = 2, Cramer’s V = 0.029, p = 0.719 |

| Never | 33 (4.2%) | 16 (4.5%) | 17 (4.0%) | ||

| Sometimes | 190 (24.3%) | 90 (25.4%) | 100 (23.4%) | ||

| Do you communicate the bad news sequentially and in an organized manner, not giving more information until you are sure that the information already given has been digested? | Always | 515 (65.9%) | 222 (62.7%) | 293 (68.5%) | χ2 = 2.970, df = 2, Cramér = 0.062, p = 0.226 |

| Never | 26 (3.3%) | 12 (3.4%) | 14 (3.3%) | ||

| Sometimes | 241 (30.8%) | 120 (33.9%) | 121 (28.3%) | ||

| Do you ask a question to find out how the patient is feeling? | Always | 465 (59.5%) | 198 (55.9%) | 267 (62.4%) | χ2 = 3.741, df = 2, Cramér = 0.069, p = 0.154 |

| Never | 53 (6.8%) | 24 (6.8%) | 29 (6.8%) | ||

| Sometimes | 264 (33.8%) | 132 (37.3%) | 132 (30.8%) | ||

| In terms of the feelings, fears, and worries of the patient, do you verbally express your understanding or responsiveness? | Always | 485 (62.0%) | 222 (62.7%) | 263 (61.4%) | χ2 = 2.233, df = 2, Cramér = 0.053, p = 0.327 |

| Never | 42 (5.4%) | 23 (6.5%) | 19 (4.4%) | ||

| Sometimes | 255 (32.6%) | 109 (30.8%) | 146 (34.1%) | ||

| When the patient’s response is anxiety, fear, sadness, or aggression, do you maintain an attitude of active listening? | Always | 535 (68.4%) | 235 (66.4%) | 300 (70.1%) | χ2 = 1.595, df = 2, Cramér = 0.045, p = 0.451 |

| Never | 28 (3.6%) | 12 (3.4%) | 16 (3.7%) | ||

| Sometimes | 219 (28.0%) | 107 (30.2%) | 112 (26.2%) | ||

| Do you show support and understanding non-verbally? | Always | 468 (59.8%) | 198 (55.9%) | 270 (63.1%) | χ2 = 5.655, df = 2, Cramér = 0.085, p = 0.059 |

| Never | 56 (7.2%) | 32 (9.0%) | 24 (5.6%) | ||

| Sometimes | 258 (33.0%) | 124 (35.0%) | 134 (31.3%) | ||

| When you communicate bad news, do you present yourself assertively, expressing your thoughts confidently? | Always | 453 (57.9%) | 191 (54.0%) | 262 (61.2%) | χ2 = 4.194, df = 2, Cramér = 0.073, p = 0.123 |

| Never | 38 (4.9%) | 19 (5.4%) | 19 (4.4%) | ||

| Sometimes | 291 (37.2%) | 144 (40.7%) | 147 (34.3%) | ||

| Do you observe the emotions that have emerged in the patient following the communication of bad news? | Always | 496 (63.4%) | 219 (61.9%) | 277 (64.7%) | χ2 = 1.495, df = 2, Cramér = 0.044, p = 0.474 |

| Never | 47 (6.0%) | 25 (7.1%) | 22 (5.1%) | ||

| Sometimes | 239 (30.6%) | 110 (31.1%) | 129 (30.1%) | ||

| Do you ensure that at the end of the conversation the patient has no further doubts or questions? | Always | 523 (66.9%) | 232 (65.5%) | 291 (68.0%) | χ2 = 3.363, df = 2, Cramér = 0.066, p = 0.186 |

| Never | 28 (3.6%) | 9 (2.5%) | 19 (4.4%) | ||

| Sometimes | 231 (29.5%) | 113 (31.9%) | 118 (27.6%) | ||

| Do you establish, if necessary, a care plan together with the patient to address the new situation? | Always | 482 (61.6%) | 209 (59.0%) | 273 (63.8%) | χ2 = 1.900, df = 2, Cramér = 0.049, p = 0.387 |

| Never | 42 (5.4%) | 21 (5.9%) | 21 (4.9%) | ||

| Sometimes | 258 (33.0%) | 124 (35.0%) | 134 (31.3%) | ||

| Do you explore the possible occurrence of challenging situations after the communication of bad news and establish a strategy for future action? | Always | 443 (56.6%) | 205 (57.9%) | 238 (55.6%) | χ2 = 0.681, df = 2, Cramér = 0.030, p = 0.712 |

| Never | 53 (6.8%) | 25 (7.1%) | 28 (6.5%) | ||

| Sometimes | 286 (36.6%) | 124 (35.0%) | 162 (37.9%) | ||

| Do you farewell the patient at the end of the conversation? | Always | 531 (67.9%) | 228 (64.4%) | 303 (70.8%) | χ2 = 3.681, df = 2, Cramér = 0.069, p = 0.159 |

| Never | 25 (3.2%) | 12 (3.4%) | 13 (3.0%) | ||

| Sometimes | 226 (28.9%) | 114 (32.2%) | 112 (26.2%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Zomia, A.S.; AlHefdhi, H.A.; Alqarni, A.M.; Aljohani, A.K.; Alshahrani, Y.S.; Alnahdi, W.A.; Algahtany, A.M.; Youssef, N.; Ghazy, R.M.; Alqahtani, A.A.; et al. Examining Saudi Physicians’ Approaches to Communicate Bad News and Bridging Generational Gaps. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182528

Al Zomia AS, AlHefdhi HA, Alqarni AM, Aljohani AK, Alshahrani YS, Alnahdi WA, Algahtany AM, Youssef N, Ghazy RM, Alqahtani AA, et al. Examining Saudi Physicians’ Approaches to Communicate Bad News and Bridging Generational Gaps. Healthcare. 2023; 11(18):2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182528

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Zomia, Ahmed Saad, Hayfa A. AlHefdhi, Abdulrhman Mohammed Alqarni, Abdullah K. Aljohani, Yazeed Sultan Alshahrani, Wejdan Abdullah Alnahdi, Aws Mubarak Algahtany, Naglaa Youssef, Ramy Mohamed Ghazy, Ali Abdullah Alqahtani, and et al. 2023. "Examining Saudi Physicians’ Approaches to Communicate Bad News and Bridging Generational Gaps" Healthcare 11, no. 18: 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182528

APA StyleAl Zomia, A. S., AlHefdhi, H. A., Alqarni, A. M., Aljohani, A. K., Alshahrani, Y. S., Alnahdi, W. A., Algahtany, A. M., Youssef, N., Ghazy, R. M., Alqahtani, A. A., & Deajim, M. A. (2023). Examining Saudi Physicians’ Approaches to Communicate Bad News and Bridging Generational Gaps. Healthcare, 11(18), 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182528