Healthcare Research in Mass Religious Gatherings and Emergency Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

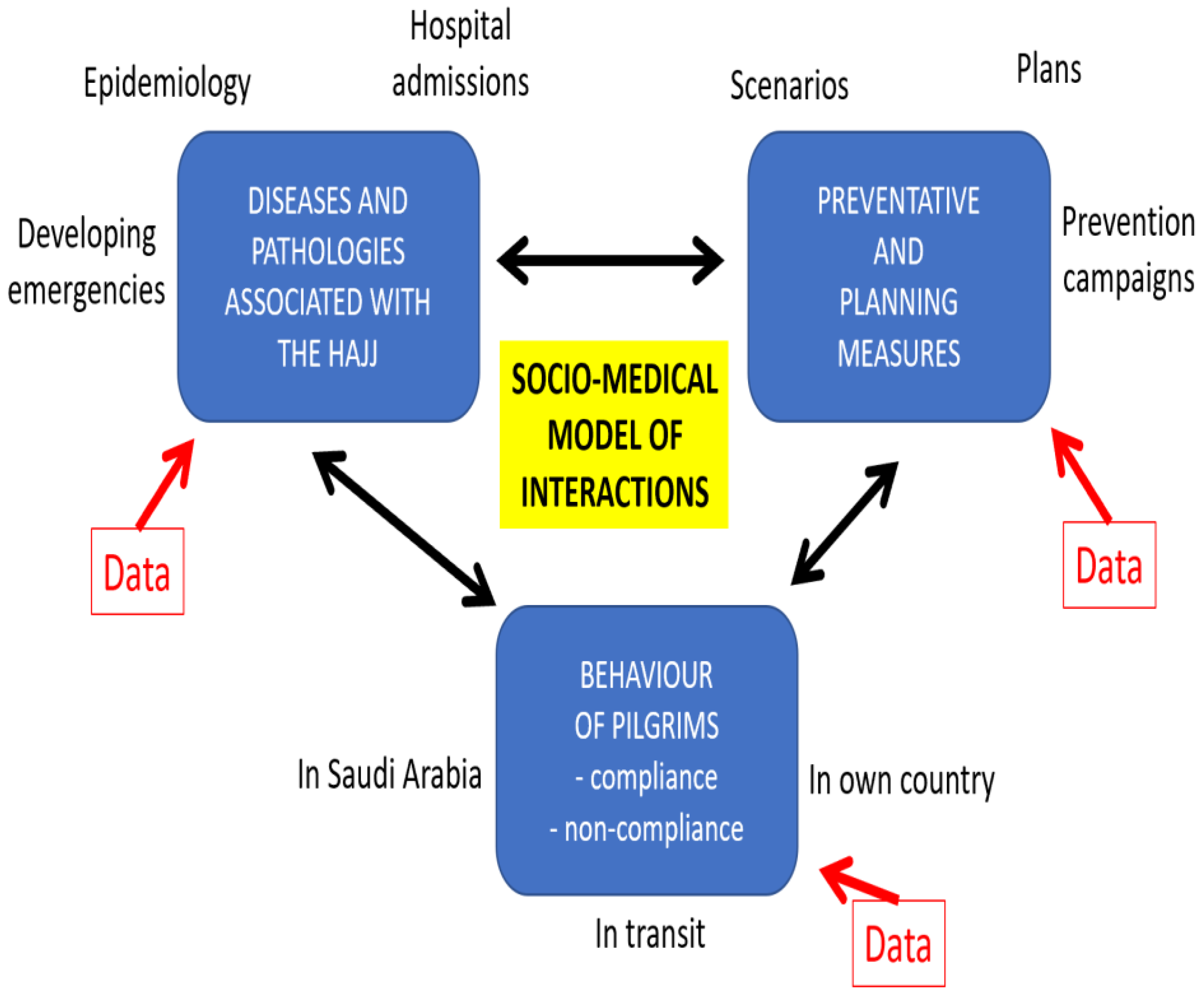

3. Results

3.1. The Hajj

3.1.1. Health Risks during the Hajj

3.1.2. Infectious-Related Health Risk

3.1.3. Non-Infectious-Related Health Risks

3.1.4. Preventative Health Measures Recommended by the Ministry of Health

3.1.5. Adherence to Recommended Preventative Health Measures

3.2. Kumbh Mela

3.2.1. Health Risks during the Kumbh Mela

3.2.2. Infectious Disease Risk

3.2.3. Non-Infectious Disease Risk

3.2.4. Preventative Health Measures Recommended by the Ministry of Health

3.2.5. Adherence to Recommended Preventative Health Measures

3.3. Arba’een Pilgrimage

3.4. Christian Mass Gatherings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, D. Book Abstract: How to Write an Emergency Plan by David Alexander; Reproduced by Permission. Health Emergencies Disasters Q. 2017, 1, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (WHO). Avian Influenza. who.int. 2019. Available online: http://www.wpro.who.int/china/topics/avian_influenza/en/ (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Aitsi-Selmi, A.; Murray, V.; Heymann, D.; McCloskey, B.; Azhar, E.I.; Petersen, E.; Zumla, A.; Dar, O. Reducing risks to health and wellbeing at mass gatherings: The role of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otter, J.A.; Donskey, C.; Yezli, S.; Douthwaite, S.; Goldenberg, S.D.; Weber, D.J. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: The possible role of dry surface contamination. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016, 92, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Rabeeah, A.; Memish, Z.A.; Zumla, A.; Shafi, S.; McCloskey, B.; Moolla, A.; Barbeschi, M.; Heymann, D.; Horton, R. Mass gatherings medicine and global health security. Lancet 2012, 380, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Alotaibi, B.M. Mass gatherings and mass gatherings health. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 729–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNISDR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva: UNISDR. 2015. Available online: www.unisdr.org (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC Health Information for International Travel 2014: The Yellow Book; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013.

- Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-exec/ (accessed on 29 October 2017).

- Available online: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia-pacific/2015/01/million-join-parade-jesus-icon-manila-20151973625966141.html (accessed on 29 October 2017).

- Cronin, P.; Ryan, F.; Coughlan, M. Undertaking a literature review: A step-by-step approach. Br. J. Nurs. 2008, 17, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamati, P.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V. Hajj stampede in Mina, 2015: Need for intervention. Arch. Trauma Res. 2016, 5, e36308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatrad, A.R.; Sheikh, A. Hajj: Journey of a lifetime. BMJ 2005, 330, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Hajj 1439 H. Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/hajj/pages/healthregulations.aspx (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Shujaa, A.; Alhamid, S. Health response to Hajj mass gathering from emergency perspective, narrative review. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 15, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leggio, W.J.; Mobrad, A.; D’Alessandro, K.J.; Krtek, M.G.; Alrazeeni, D.M.; Sami, M.A.; Raynovich, W. Experiencing Hajj: A phenomenological qualitative study of paramedic students. Australas. J. Paramed. 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoety, D.A.; El-Bakri, N.K.; Almowalld, W.O.; Turkistani, Z.A.; Bugis, B.H.; Baseif, E.A.; Melbari, M.H.; Alharbi, K.; Abu-Shaheen, A. Characteristics of Heat Illness during Hajj: A Cross-Sectional Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5629474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbin, J.C.A.; Alfelali, M.; Barasheed, O.; Taylor, J.; Dwyer, D.E.; Kok, J.; Booy, R.; Holmes, E.C.; Rashid, H. Multiple Sources of Genetic Diversity of Influenza A Viruses during the Hajj. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00096-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, J.; Thu, M.; Arshad, N.; Van Der Putten, M. Mass Gatherings and Public Health: Case Studies from the Hajj to Mecca. Ann. Glob. Health 2017, 83, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Memish, Z.A.; Assiri, A.M.; Hussain, R.; AlOmar, I.; Stephens, G. Detection of Respiratory Viruses Among Pilgrims in Saudi Arabia During the Time of a Declared Influenza A(H1N1) Pandemic. J. Travel Med. 2011, 19, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balkhy, H.H.; Memish, Z.A.; Bafaqeer, S.; Almuneef, M.A. Influenza a Common Viral Infection among Hajj Pilgrims: Time for Routine Surveillance and Vaccination. J. Travel Med. 2004, 11, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alzeer, A.H. Respiratory tract infection during Hajj. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, S.M.; Akbar, H.O.; Qari, Y.A.; Fathaldin, O.A.; Al-Rashed, R.S. Pattern of admission to hospitals during muslim pilgrimage (Hajj). Saudi Med. J. 2003, 24, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Memish, Z.A. The Hajj: Communicable and non-communicable health hazards and current guidance for pil-grims. Eurosurveillance 2010, 15, 19671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.; Al Hakeem, R.; Al Neel, O.; Danis, K.; Jasir, A.; Eibach, D. Laboratory-confirmed invasive meningococcal disease: Effect of the Hajj vaccination policy, Saudi Arabia, 1995 to 2011. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.; Memish, Z. Potential risk for drug resistance globalization at the Hajj. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Struelens, M.J.; Monnet, D.L.; Magiorakos, A.P.; O’Connor, F.S.; Giesecke, J. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1-producing Enterobacteriaceae: Emergence and response in Europe. Eurosurveillance 2010, 15, 19716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashani, M.; Alfelali, M.; Azeem, M.I.; Fatema, F.N.; Barasheed, O.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Booy, R. Barriers of vac-cinations against serious bacterial infections among Australian Hajj pilgrims. Postgrad. Med. 2016, 128, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Althimiri, N.A.; BinDhim, N.F. Saudi Hajj pilgrims’ preparation and uptake of health preventive measures during Hajj 2017. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Arabia to Allow Only ‘Immunised’ Pilgrims to Mecca|Coronavirus Pandemic News|Al Jazeera. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/4/5/saudi-to-permit-only-vaccinated-pilgrims-from-ramadan-on (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- In pictures: Masks and Social Distancing at Downsized Hajj-BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-57875572 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S.; Salaheddine, I.; Parola, P.; Brouqui, P. Preventive measures against MERS-CoV for Hajj pilgrims. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 829–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alfelali, M.; Rashid, H. Prevalence of influenza at Hajj: Is it correlated with vaccine uptake? Infect. Disord.-Drug Targets 2014, 14, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasheed, O.; Alfelali, M.; Mushta, S.; Bokhary, H.; Alshehri, J.; Attar, A.A.; Booy, R.; Rashid, H. Uptake and effectiveness of facemask against respiratory infections at mass gatherings: A systematic review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deris, Z.Z.; Hasan, H.; Sulaiman, S.A.; Wahab, M.S.A.; Naing, N.N.; Othman, N.H. The Prevalence of Acute Respiratory Symptoms and Role of Protective Measures Among Malaysian Hajj Pilgrims. J. Travel Med. 2010, 17, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benkouiten, S.; Charrel, R.; Belhouchat, K.; Drali, T.; Nougairede, A.; Salez, N.; Memish, Z.A.; Al Masri, M.; Fournier, P.-E.; Raoult, D.; et al. Respiratory Viruses and Bacteria among Pilgrims during the 2013 Hajj. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1821–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, T.A.; Ghabrah, T.M. Meningococcal, influenza virus, and hepatitis B virus vaccination coverage level among health care workers in Hajj. BMC Infect. Dis. 2007, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Memish, Z.A.; Yezli, S.; Almasri, M.; Assiri, A.; Turkestani, A.; Findlow, H.; Bai, X.; Borrow, R. Meningococcal serogroup A, C, W, and Y serum bactericidal antibody profiles in Hajj pilgrims. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 28, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salamati, P.; Razavi, S.M.; Saeednejad, M. Vaccination in Hajj: An overview of the recent findings. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Gautret, P.; Brouqui, P. A comprehensive review of the Kumbh Mela: Identifying risks for spread of infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- David, S.; Roy, N. Public health perspectives from the biggest human mass gathering on earth: Kumbh Mela, India. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehta, D.; Yadav, D.S.; Mehta, N.K. A literature review on management of mega event-Maha Kumbh (Sim-hastha). Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2014, 1, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Quadri, S.A.; Padala, P.R. An Aspect of Kumbh Mela Massive Gathering and COVID-19. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2021, 8, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsari, S.; Greenough, P.G.; Kazi, D.; Heerboth, A.; Dwivedi, S.; Leaning, J. Public health aspects of the world’s largest mass gathering: The 2013 Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, India. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, M. Harvard doctors give Kumbh health facilities thumbs up. Times of India, 20 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karampourian, A.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D.; Ghomiyan, Z. Fatalism at the Arbaeen Ceremony. J. Saf. Promot. Inj. Prev. 2017, 5, 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, J.C. Luneta Mass Is Largest Papal Event in History. ABS-CBN News. Available online: ABS-CBNnews.com (accessed on 9 May 2017).

- Lillie, A.K. The practice of pilgrimage in palliative care: A case study of Lourdes. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2005, 11, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q.A.; Memish, Z.A. From the “Madding Crowd” to mass gatherings-religion, sport, culture and public health. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 28, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patz, J.A.; Olson, S.H.; Uejio, C.K.; Gibbs, H.K. Disease Emergence from Global Climate and Land Use Change. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 92, 1473–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, A.; Batty, M.; Hayashi, K.; Al Bar Marcozzi, D.O.; Memish, Z.A. Crowd and Environmental management during mass gatherings. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skinner, C.S.; Tiro, J.; Champion, V.L. Background on the health belief model. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 75, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D.E. Confronting Catastrophe; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, J.S. Prevalence, incidence, morbidity and mortality rates of COPD in Saudi Arabia: Trends in burden of COPD from 1990 to 2019. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, J.S.; Aldhahir, A.M.; AlRabeeah, S.M.; Alsenani, L.B.; Alsharif, H.M.; Alshehri, A.Y.; Alenazi, M.M.; Alnasser, M.; Alqahtani, A.S.; AlDraiwiesh, I.A.; et al. Future Acceptability of Respiratory Virus Infection Control Interventions in General Population to Prevent Respiratory Infections. Medicina 2022, 58, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, J.S.; Aquilina, J.; Bafadhel, M.; Bolton, C.E.; Burgoyne, T.; Holmes, S.; King, J.; Loots, J.; McCarthy, J.; Quint, J.K.; et al. Research priorities for exacerbations of COPD. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 824–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, N.; Reicher, S. Mass gatherings, health, and well-being: From risk mitigation to health promotion. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2021, 15, 114–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vortmann, M.; Balsari, S.; Holman, S.R.; Greenough, P.G. Water, sanitation, and hygiene at the world’s largest mass gathering. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2015, 17, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almehmadi, M.; Alqahtani, J.S. Healthcare Research in Mass Religious Gatherings and Emergency Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020244

Almehmadi M, Alqahtani JS. Healthcare Research in Mass Religious Gatherings and Emergency Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Healthcare. 2023; 11(2):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020244

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmehmadi, Mater, and Jaber S. Alqahtani. 2023. "Healthcare Research in Mass Religious Gatherings and Emergency Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review" Healthcare 11, no. 2: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020244