The Effects of a Simulation-Based Patient Safety Education Program on Compliance with Patient Safety, Perception of Patient Safety Culture, and Educational Satisfaction of Operating Room Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

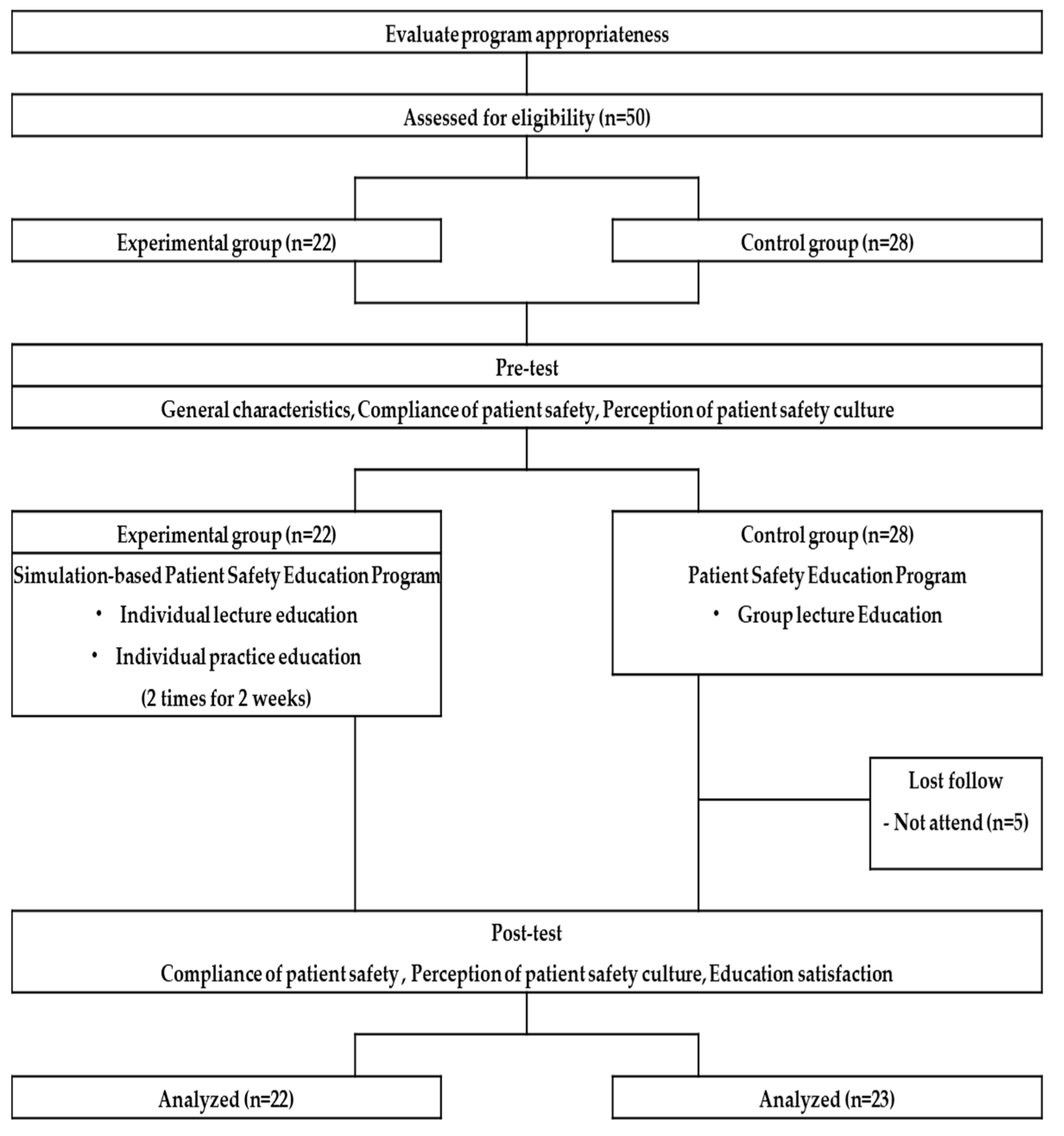

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Research Participants

2.3. Research Procedure

2.4. Simulation-Based Patient Safety Education Program

2.4.1. Program Development

2.4.2. Program Progress and Contents

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. General Characteristics

2.5.2. Compliance with Patient Safety

2.5.3. Perception of Patient Safety Culture

2.5.4. Satisfaction with Education

2.6. Analysis

- (1)

- The general characteristics of the research participants and the homogeneity of research variables were analyzed using the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and t-test

- (2)

- The effect of the simulation-based patient safety education program on operating room nurses was analyzed using ANCOVA, which homogeneously processed predefined values using a covariate. All statistical significance levels were p < 0.05

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Homogeneity Test of General Characteristics

3.2. Effects of the Simulation-Based Patient Safety Education Program

3.2.1. Compliance with Patient Safety

3.2.2. Perception of Patient Safety Culture

3.2.3. Educational Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AHRQ. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (Report No. 10(14)-EHC063-EF); Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; AHRQ Publication: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shouhed, D.; Gewertz, B.; Wiegmann, D.; Catchpole, K. Integrating human factors research and surgery: A review. Arch. Surg. 2012, 147, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugur, E.; Kara, S.; Yildirim, S.; Akbal, E. Medical errors and patient safety in the operating room. Age 2016, 33, 19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ock, M.S.; Koo, H.M.; Seo, H.J.; Beak, H.J.; Kim, M.J. Patient Safety Statistical Yearbook; KOIHA: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Habahbeh, A.A.; Alkhalaileh, M.A. Effect of an educational program on the attitudes towards patient safety of operation room nurses. Br. J. Nursing 2020, 29, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Choi, E.H.; Lee, K.S.; Chung, K.A. A study on perception and nursing activity for patient safety of operating room nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2016, 17, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argaw, S.T.; Troncoso-Pastoriza, J.R.; Lacey, D.; Florin, M.; Calcavecchia, F.; Anderson, D.; Burleson, W.; Vogel, J.-M.; O’Leary, C.; Eshaya-Chauvin, B.; et al. Cybersecurity of hospitals: Discussing the challenges and working towards mitigating the risks. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.W.; Lee, W.J. Influence of safety control, nursing professionalism, and burnout on patient safety management activities among operating room nurses. J. Muscle Jt. Health 2023, 30, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.S. Statistical Yearbook of Medical Dispute Mediation and Arbitration in 2022; Korea Medical Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Agency: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wheway, J.; Agbabiaka, T.B.; Ernst, E. Patient safety incidents from acupuncture treatments: A review of reports to the national patient safety agency. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2012, 24, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.R.; Shin, E.H. Review on patient safety education for undergraduate/pre-registration curricula in health professions. Korean Public Health Res. 2016, 42, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Ministry of Health and Welfare Statistical Year Book; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.M.; Kwon, S.H. Factors influencing patient safety management activities among general hospital operating room nurses. J. Korean Nurs. Adm. Acad. Soc. 2023, 29, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomaa, C.; Dubois, C.A.; Caron, I.; Homme, A.P. Staffing teamwork and scope of practice: Analysis of the association with patient safety in the context of rehabilitation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Patient Safety, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/patient-safety#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Kim, A.Y.; Lee, H.I. Influences of teamwork and job burnout on patient safety management activities among operating room nurses. J. Korean Nurs. Adm. Acad. Soc. 2022, 28, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.K. A Study on the Impact Factors of the Effectiveness of Patient Safety: Focusing on the Perception of Operating Room Nurses; University of Catholic: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.M.; Kim, S.H. The effect of operating room nurse’s patient safety competency and perception of teamwork on safety management activities. J. Digit. Converg. 2018, 16, 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H.S.; Kong, J.H.; Jeon, M.Y. Factors influencing confidence in patient safety management in nursing students. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2017, 8, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Hahn, S.H. Effect of simulation- based practice on clinical performance and problem solving process for nursing students. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2011, 17, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, P.G. Simulation in nursing education: A review or the research. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Kim, S.S. A safety simulation program for operating room nurses. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2018, 18, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J. Development and evaluation of a simulation-based education course for nursing students. Korean Acad. Soc. Adult Nurs. 2008, 20, 548–560. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Jeong, H.C. Comparison of post-training nursing performance using simulation and multimedia: On the case of difficulty breathing. J. Korean Soc. Simul. Nurs. 2018, 6, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Oh, P.J. Effects of the use of high-fidelity human simulation in nursing education: A meta-analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. 2015, 54, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.Y.; Kim, K.H. Development and evaluation of competency based quality improvement and safety education program for undergraduate nursing students. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2016, 28, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.S.; Kim, S.S. Operating room nurses want differentiated education for perioperative competencies-based on the clinical Ladder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Kang, H.Y. The development and effects of a tailored simulation learning program for new nursing staffs in intensive care units and emergency rooms. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Edu. 2015, 21, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, K.H.; Choi, M.H.; Kang, M.K. A study on levels of awareness of nosocomial infection and management practices by operating room nurses. Korean J. Funda Nurs. 2004, 11, 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.H.; Ha, R.M.; Kim, E.H.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Shin, H.M.; Jeoun, H.S. A study on the awareness and performance of patient safety management in operating room nurses. Korea Assoc. Oper. Room Nurs. 2008, 16, 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.S. Important awareness and compliance on practice safety for nurses working in operating rooms. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2011, 12, 5748–5758. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, M.Y.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, M.J.; Kwon, E.J.; Shin, E.J.; Park, Y.W.; Jeong, S.J.; Yu, S.M. The effect of surgery patient safety improvement program on nurse’s perception of patient safety. Korea Assoc. Oper. Room Nurs. 2008, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, E.J. A Study on Practical Education Focused on Nursing Officers; University of Hanyang: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.M.; Ko, Y.J. Effects of simulation-based preoperative and postoperative care nursing problem on problem solving ability, critical thinking disposition, and academic self-efficacy of nursing students. Kor Assoc. Lear Cent. Curr. Instt. 2017, 17, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Jang, K.S. Effects of a simulation-based education on cardio-pulmonary emergency care knowledge, clinical performance ability and problem solving process in new nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2011, 41, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, R.G. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, K.A.; Kardong-Edgren, S.; Willhaus, J. An updated review of published simulation evaluation instruments. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013, 9, e393–e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Learning Goals | ||

| ||

| Session | Contents | Time (min) |

| Prebriefing stage |

| 20 |

| Simulation stage | 1. Patient Safety and Infection Control

| 40 × 2 rate = 80 |

2. Patient safety and operating room management

| ||

| Debriefing stage |

| 20 |

| General Characteristics | Experimental Group (n = 22) | Control Group (n = 23) | X2/t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD /n (%) | M ± SD /n (%) | ||||

| Age (year) | 35.82 ± 5.40 | 32.96 ± 5.34 | 1.79 | 0.081 | |

| Operation room experience (year) | 11.26 ± 6.46 | 10.20 ± 5.72 | 0.58 | 0.563 | |

| Working time (h/wk) | 42.77 ± 4.24 | 43.44 ± 2.73 | −0.63 | 0.535 | |

| Gender | Women | 19 (86.4) | 17 (73.9) | 1.09 | 0.297 * |

| Men | 3 (13.6) | 6 (26.1) | |||

| Education | Associate (3 years) | 6 (27.3) | 4 (17.4) | 1.81 | 0.406 * |

| Bachelor (4 years) | 11 (50.0) | 16 (69.6) | |||

| ≥Graduate school | 5 (22.7) | 3 (13.0) | |||

| Work type | 3 shifts | 16 (72.7) | 15 (65.2) | 0.30 | 0.749 |

| General shift | 6 (27.3) | 8 (34.8) | |||

| Position | Clinical Nurse | 9 (40.9) | 8 (34.8) | 0.18 | 0.672 |

| Nurse/Charge Nurse | 13 (59.1) | 15 (65.2) | |||

| Department of operating room | Major part | 12 (54.5) | 13 (56.5) | 0.02 | 0.991 * |

| Minor part | 4 (18.2) | 4 (17.4) | |||

| Other | 6 (27.3) | 6 (26.1) | |||

| Number of operations (n/day) | ≤3 | 6 (27.3) | 12 (52.2) | 3.07 | 0.266 |

| 4 | 6 (27.3) | 5 (21.7) | |||

| ≥5 | 10 (45.4) | 6 (26.1) | |||

| Experience with patient safety education | Yes | 18 (81.8) | 19 (82.6) | 0.05 | 0.945 * |

| No | 4 (18.2) | 4 (17.4) | |||

| Experience with simulation education | Yes | 7 (31.8) | 7 (30.4) | 0.10 | 0.920 |

| No | 15 (68.2) | 16 (69.6) |

| Division | Categories | Exp.(n = 22) | Cont.(n = 23) | F * | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Posttest | Pretest | Posttest | ||||||||

| M ± SD | Interpretation | M ± SD | Interpretation | M ± SD | Interpretation | M ± SD | Interpretation | ||||

| Compliance with patient safety | Tissue specimen management | 4.95 ± 0.14 | Very high | 4.95 ± 0.14 | Very high | 4.99 ± 0.04 | Very high | 4.81 ± 0.29 | Very high | 4.44 | 0.041 |

| Management of infectious patients | 4.79 ± 0.36 | Very high | 4.71 ± 0.22 | Very high | 4.84 ± 0.28 | Very high | 4.45 ± 0.53 | Very high | 5.94 | 0.019 | |

| Preoperative check | 4.96 ± 1.22 | Very high | 4.95 ± 0.13 | Very high | 4.96 ± 0.11 | Very high | 4.87 ± 0.27 | Very high | 1.46 | 0.233 | |

| Use of electrocautery | 4.97 ± 0.15 | Very high | 4.98 ± 0.05 | Very high | 4.87 ± 0.27 | Very high | 4.78 ± 0.38 | Very high | 4.60 | 0.038 | |

| Management of medical equipment and using laser light | 4.89 ± 0.31 | Very high | 4.89 ± 0.13 | Very high | 4.91 ± 0.22 | Very high | 4.59 ± 0.70 | Very high | 5.13 | 0.029 | |

| Preventing falls and skin damage | 4.96 ± 0.08 | Very high | 4.93 ± 0.14 | Very high | 4.95 ± 0.10 | Very high | 4.85 ± 0.19 | Very high | 2.37 | 0.131 | |

| Gauze count | 5.00 ± 0.15 | Very high | 4.97 ± 0.04 | Very high | 4.98 ± 0.04 | Very high | 4.96 ± 0.07 | Very high | 0.240 | 0.625 | |

| Total | 34.51 ± 1.05 | 34.39 ± 0.54 | 34.57 ± 0.69 | 33.33 ± 1.97 | 6.80 | 0.013 | |||||

| Perception of patient safety culture | 4.00 ± 0.62 | High | 4.31 ± 0.56 | Very high | 4.12 ± 0.59 | High | 3.96 ± 0.54 | High | 6.70 | 0.013 | |

| Educational satisfaction | 4.06 ± 0.48 | High | 4.47 ± 0.42 | Very high | 4.13 ± 0.57 | High | 3.85 ± 0.69 | High | 21.03 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, O.; Jeon, M.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Jeong, H. The Effects of a Simulation-Based Patient Safety Education Program on Compliance with Patient Safety, Perception of Patient Safety Culture, and Educational Satisfaction of Operating Room Nurses. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212824

Park O, Jeon M, Kim M, Kim B, Jeong H. The Effects of a Simulation-Based Patient Safety Education Program on Compliance with Patient Safety, Perception of Patient Safety Culture, and Educational Satisfaction of Operating Room Nurses. Healthcare. 2023; 11(21):2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212824

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, OkBun, MiYang Jeon, MiSeon Kim, ByeolAh Kim, and HyeonCheol Jeong. 2023. "The Effects of a Simulation-Based Patient Safety Education Program on Compliance with Patient Safety, Perception of Patient Safety Culture, and Educational Satisfaction of Operating Room Nurses" Healthcare 11, no. 21: 2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212824

APA StylePark, O., Jeon, M., Kim, M., Kim, B., & Jeong, H. (2023). The Effects of a Simulation-Based Patient Safety Education Program on Compliance with Patient Safety, Perception of Patient Safety Culture, and Educational Satisfaction of Operating Room Nurses. Healthcare, 11(21), 2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212824