Evidence-Based Implementation of the Family-Centered Model and the Use of Tele-Intervention in Early Childhood Services: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.4. Selection of Studies

2.5. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

3. Results

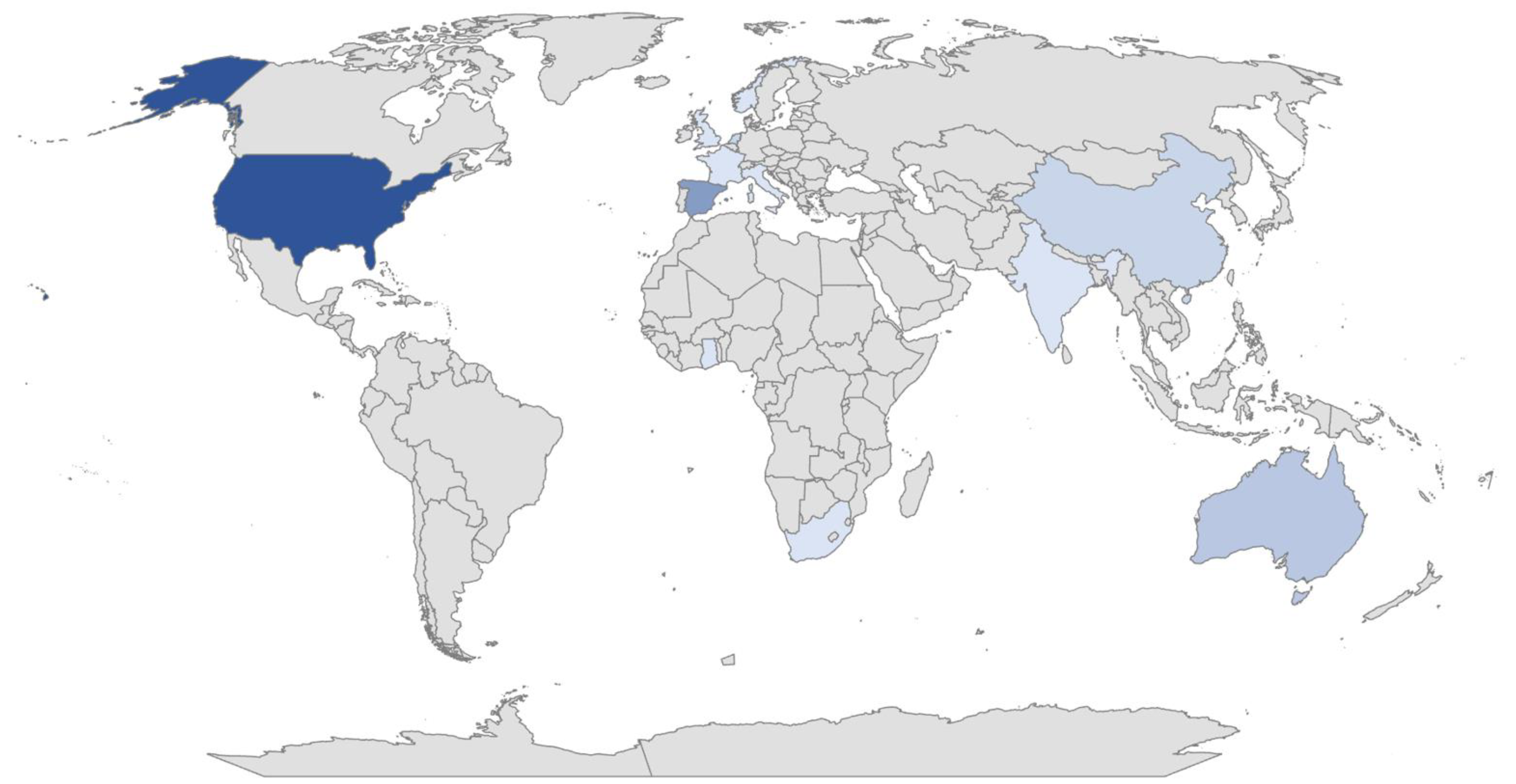

3.1. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3.1.1. The Participation of Children and Family Is Facilitated and Improved by the Family-Centered Model of Care

3.1.2. Feelings of Competence, Self-Efficacy, Satisfaction and Empowerment in Practitioners and Families Have a Positive Impact on Quality of Life

3.1.3. Use of Tele-Intervention as a Tool for Prevention and Intervention

3.1.4. Communication during Tele-Intervention May Be Limited by Logistical Barriers

3.1.5. Tele-Intervention as a Possible Solution to Contextual Barriers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations of the Study

5.2. Implications for the Practice and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Web Of Science | TI = (Early Intervention OR Educational Early OR Early Intervention (Education) OR Intervention, Early (Education) OR Early Intervention, Education OR Education Early Intervention OR Intervention, Education Early OR Early Intervention Education OR Education, Early Intervention OR Intervention Education, Early OR Head Start Program* OR Program, Head Start) NOT TS = (Adult*) AND TS = (Child* OR Infant* OR Toddler* OR Preschool*) AND TI = (Family centered program* OR Family-Centered care* OR Family Centered Early Intervention*) |

| PubMed | (“Early Intervention” OR “Educational Early” OR “Early Intervention (Education)” OR “Intervention, Early (Education)” OR “Early Intervention, Education” OR “Education Early Intervention” OR “Intervention, Education Early” OR “Early Intervention Education” OR “Education, Early Intervention” OR “Intervention Education, Early” OR “Head Start Program” OR “Head Start Programs” OR “Program, Head Start” [Title]) AND (“Child*” OR “Infant*” OR “Toddler*” OR “Preschool*” [Title/Abstract]) NOT (“Adult*” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Family centered program*” OR “Family-Centered care*” OR “Family Centered Early Intervention*” [Title]) |

| Scopus | TITLE (“Early Intervention” OR “Educational Early” OR “Early Intervention (Education)” OR “Intervention, Early (Education)” OR “Early Intervention, Education” OR “Education Early Intervention” OR “Intervention, Education Early” OR “Early Intervention Education” OR “Education, Early Intervention” OR “Intervention Education, Early” OR “Head Start Program*” OR “Program, Head Start”) not TITLE-ABS-KEY ( adult*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “Child*” OR “Infant*” OR “Toddler*” OR “Preschool*”) AND TITLE (“Family centered program*” OR “Family-Centered care*” OR “Family Centered Early Intervention*”) |

| Web Of Science | TI = (Telehealth OR Telemedicine OR Telerehabilitation* OR mHealth OR Tele-rehabilitation* OR Remote Rehabilitation* OR Rehabilitation*, Remote OR Virtual Rehabilitation* OR Rehabilitation*, Virtual OR Tele-Referral* OR Tele Referral* OR Virtual Medicine OR Medicine, Virtual OR Tele-Intensive Care OR Tele Intensive Care OR Tele-ICU OR Tele ICU OR Mobile Health OR Health, Mobile OR mHealth OR Telehealth OR eHealth) AND TI = (Early Intervention OR Educational Early OR Early Intervention (Education) OR Intervention, Early (Education) OR Early Intervention, Education OR Education Early Intervention OR Intervention, Education Early OR Early Intervention Education OR Education, Early Intervention OR Intervention Education, Early OR Head Start Program OR Head Start Programs OR Program, Head Start) NOT TS = (Adult*) AND TS= (Child* AND Infant*) |

| PubMed | (“Telehealth” OR “Telemedicine” OR “Telerehabilitation*” OR “mHealth” OR “Tele-rehabilitation*” OR “Remote Rehabilitation*” OR “Rehabilitation*, Remote” OR “Virtual Rehabilitation*” OR “Rehabilitation*, Virtual” OR “Tele-Referral*” OR “Tele Referral*” OR “Virtual Medicine” OR “Medicine, Virtual” OR “Tele-Intensive Care” OR “Tele Intensive Care” OR “Tele-ICU” OR “Tele ICU” OR “Mobile Health” OR “Health, Mobile” OR “mHealth” OR “Telehealth” OR “eHealth” [Title]) AND (“Early Intervention” OR “Educational Early” OR “Early Intervention (Education)” OR “Intervention, Early (Education)” OR “Early Intervention, Education” OR “Education Early Intervention” OR “Intervention, Education Early” OR “Early Intervention Education” OR “Education, Early Intervention” OR “Intervention Education, Early” OR “Head Start Program” OR “Head Start Programs” OR “Program, Head Start” [Title]) AND (“Child*” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Infant*” [Title/Abstract]) NOT (“Adult*” [Title/Abstract]) |

| Scopus | TITLE(“Telehealth” OR “Telemedicine” OR “Telerehabilitation*” OR “mHealth” OR “Tele-rehabilitation*” OR “Remote Rehabilitation*” OR “Rehabilitation*, Remote” OR “Virtual Rehabilitation*” OR “Rehabilitation*, Virtual” OR “Tele-Referral*” OR “Tele Referral*” OR “Virtual Medicine” OR “Medicine, Virtual” OR “Tele-Intensive Care” OR “Tele Intensive Care” OR “Tele-ICU” OR “Tele ICU” OR “Mobile Health” OR “Health, Mobile” OR “mHealth” OR “Telehealth” OR “eHealth”) AND TITLE (“Early Intervention” OR “Educational Early” OR “Early Intervention (Education)” OR “Intervention, Early (Education)” OR “Early Intervention, Education” OR “Education Early Intervention” OR “Intervention, Education Early” OR “Early Intervention Education” OR “Education, Early Intervention” OR “Intervention Education, Early” OR “Head Start Program” OR “Head Start Programs” OR “Program, Head Start”) AND TITLE (“Child*” OR “Infant*” OR “Toddler*” OR “Preschool*”) |

References

- Cruz-Hernández, J.M.; García, J.J.; Martínez, O.C.; Raso, S.M.; Villares, J.M.M. Manual de Pediatría, 4th ed.; Ergon: Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 978-84-17194-65-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan, S. Terapia Ocupacional en Pediatria. Proceso de Evaluación; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2006; ISBN 978-84-7903-981-3. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Richter, L.; Van Der Gaag, J.; Bhutta, Z.A. An Integrated Scientific Framework for Child Survival and Early Childhood Development. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e460–e472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, N.B.; Delgado-Lobete, L.; Montes-Montes, R.; Ruiz-Pérez, N.; Santos-del-Riego, S. Participation in Everyday Activities of Children with and without Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain. Children 2020, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, C.-W.; Rodger, S.; Copley, J. Parent-Reported Participation in Children with Moderate-to-Severe Developmental Disabilities: Preliminary Analysis of Associated Factors Using the ICF Framework. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2017, 64, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günal, A.; Bumin, G.; Huri, M. The Effects of Motor and Cognitive Impairments on Daily Living Activities and Quality of Life in Children with Autism. J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2019, 12, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López, J.A.; Fernández-Fidalgo, M.; Geoffrey, R.; Stucki, G.; Cieza, A. Funcionamiento y discapacidad: La Clasificación Internacional del Funcionamiento (CIF). Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2009, 83, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early Intervention Foundation What Is Early Intervention? Available online: https://www.eif.org.uk/why-it-matters/what-is-early-intervention/ (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Fontil, L.; Sladeczek, I.E.; Gittens, J.; Kubishyn, N.; Habib, K. From Early Intervention to Elementary School: A Survey of Transition Support Practices for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 88, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajo, L.C.; Candler, C.; Sarafian, A. Interventions within the Scope of Occupational Therapy to Improve Children’s Academic Participation: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7402180030p1–7402180030p32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.; Lervåg, A.; Snowling, M.J.; Buchanan-Worster, E.; Duta, M.; Hulme, C. Early Language Intervention Improves Behavioral Adjustment in School: Evidence from a Cluster Randomized Trial. J. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 92, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Honan, I. Effectiveness of Paediatric Occupational Therapy for Children with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2019, 66, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniolou, S.; Pandis, N.; Znoj, H. The Efficacy of Early Interventions for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya, A.S.; Gual, E.M.; Elvira, J.A.M.; Salas, B.L.; Cívico, F.J.A. La atención temprana en los trastornos del espectro autista (TEA). Psicol. Educ. 2015, 21, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, A.; Bulkeley, K.; Veitch, C.; Bundy, A.; Gallego, G.; Lincoln, M.; Brentnall, J.; Griffiths, S. Addressing the Barriers to Accessing Therapy Services in Rural and Remote Areas. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Alba, L.; Gray, M.; Williams, G.; Lowe, S. Early Intervention in Children (0–6 Years) with a Rare Developmental Disability: The Occupational Therapy Role. Hong Kong J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 24, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Darrah, J.; Gordon, A.M.; Harbourne, R.; Spittle, A.; Johnson, R.; Fetters, L. Effectiveness of Motor Interventions in Infants with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2016, 58, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal-Walter, F.; Waite, M.; Scarinci, N. Identifying Critical Behaviours for Building Engagement in Telepractice Early Intervention: An International e-Delphi Study. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2022, 57, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Toro Alonso, V.; Moreno, E.S. Introduction Family-Centered Model in Spain from a Perspective from the Life Family Quality. Rev. Educ. Inclusiva 2020, 13, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, M.; Leigh, G.; Arthur-Kelly, M. Practitioners’ Self-Assessment of Family-Centered Practice in Telepractice Versus In-Person Early Intervention. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 2021, 26, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, E.S.; O’Brien, J.C.; Taylor, R.R. Communicating with Intention: Therapist and Parent Perspectives on Family-Centered Care in Early Intervention. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 76, 7605205130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, R.; Brotherson, M.J.; Winton, P.; Roberts, R.; Snyder, P.; McWilliam, R.; Chandler, L.; Schrandt, S.; et al. Family Supports and Services in Early Intervention: A Bold Vision. J. Early Interv. 2007, 29, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C.J.; Espe-Sherwindt, M. Family-Centered Practices in Early Childhood Intervention. In Handbook of Early Childhood Special Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 37–55. ISBN 978-331928492-7. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderkerken, L.; Heyvaert, M.; Onghena, P.; Maes, B. Family-Centered Practices in Home-Based Support for Families with Children with an Intellectual Disability: Judgments of Parents and Professionals. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 25, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruder, M.B. Family-Centered Early Intervention: Clarifying Our Values for the New Millennium. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2000, 20, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisels, S.J.; Atkins-Burnett, S. Assessing Intellectual and Affective Development before Age Three: A Perspective on Changing Practices. Food Nutr. Bull. 1999, 20, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C.; Trivette, C. Capacity-Building Family-Systems Intervention Practices. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2009, 12, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Curran, C.J.; Mcpherson, A. A Four-Part Ecological Model of Community-Focused Therapeutic Recreation and Life Skills Services for Children and Youth with Disabilities. Child Care Health Dev. 2013, 39, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melvin, K.; Meyer, C.; Scarinci, N. What Does “Engagement” Mean in Early Speech Pathology Intervention? A Qualitative Systematised Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 2665–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.; Plahouras, J.; Johnston, B.C.; Scaffidi, M.A.; Grover, S.C.; Walsh, C.M. Virtual Reality Simulation Training for Health Professions Trainees in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD008237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosana, E.S.; Serrano, J.O. La Percepción Local Del Acceso a Los Servicios de Salud En Las Áreas Rurales. El Caso Del Pirineo Navarro. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2021, 44, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez García, L.; Herrán García, I.; de La Mano Rodero, P.; Díaz Sánchez, C.; Martínez Carrillo, J. Atención temprana en tiempos de COVID-19: Investigar la/s realidad/es de la teleintervención en las prácticas centradas en la familia. Siglo Cero 2021, 1, 75–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, K.T.; Stredler-Brown, A. A Model of Early Intervention for Children with Hearing Loss Provided through Telepractice. Volta. Rev. 2012, 112, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) Telemedicine 1993. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh?Db=mesh&Cmd=DetailsSearch&Term=%22Telemedicine%22%5BMeSH+Terms%5D (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Olsen, S.; Fiechtl, B.; Rule, S. An Evaluation of Virtual Home Visits in Early Intervention: Feasibility of “Virtual Intervention”. Volta. Rev. 2012, 112, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Clasificación Internacional Del Funcionamiento, de la Discapacidad y de la Salud: CIF; Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS): Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; ISBN 92-4-354542-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.; Greenberg, J.; Stillman, D. Zotero 2006. Available online: https://www.zotero.org/download/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50: A Guideline Developer’s Handbook; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: Edinburgh, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-905813-25-4. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.; Lee, E. Effectiveness of Mobile Health Application Use to Improve Health Behavior Changes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2018, 24, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, H.; Seccurro, D.; Dorich, J.; Rice, M.; Schwartz, T.; Harpster, K. “Even Though a Lot of Kids Have It, Not a Lot of People Have Knowledge of It”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Perspectives of Parents of Children with Cerebral/Cortical Visual Impairment. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 135, 104443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rico, G.; García-Grau, P.; Cañadas, M.; González-García, R.J. Social Validity of Telepractice in Early Intervention: Effectiveness of Family-Centered Practices. Fam. Relat. 2023, 72, 2535–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, R.B.; Dirks, E. Diversity of Child and Family Characteristics of Children with Hearing Loss in Family-Centered Early Intervention in The Netherlands. JCM 2022, 11, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subinas-Medina, P.; Garcia-Grau, P.; Gutierrez-Ortega, M.; Leon-Estrada, I. Family-Centered Practices in Early Intervention: Family Confidence, Competence, and Quality of Life. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2022, 14, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Chen, H.; Miller, H.; Miller, A.; Colombi, C.; Chen, W.; Ulrich, D.A. Assessing the Satisfaction and Acceptability of an Online Parent Coaching Intervention: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 859145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukaruppan, S.S.; Cameron, C.; Campbell, Z.; Krishna, D.; Moineddin, R.; Bharathwaj, A.; Poomariappan, B.M.; Mariappan, S.; Boychuk, N.; Ponnusamy, R.; et al. Impact of a Family-Centred Early Intervention Programme in South India on Caregivers of Children with Developmental Delays. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 2410–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, J.M.; Dunst, C.J.; Hamby, D.W.; Balcells-Balcells, A.; García-Ventura, S.; Baqués, N.; Giné, C. Relationships between Family-Centred Practices and Parent Involvement in Early Childhood Intervention. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, E.; Szarkowski, A. Family-Centered Early Intervention (FCEI) Involving Fathers and Mothers of Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing: Parental Involvement and Self-Efficacy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Finch, M.; Sutherland, R.; Kingsland, M.; Wolfenden, L.; Wedesweiler, T.; Herrmann, V.; Yoong, S.L. An mHealth Intervention to Reduce the Packing of Discretionary Foods in Children’s Lunch Boxes in Early Childhood Education and Care Services: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e27760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Berentson, G.; Roberts, H.; McMorris, C.; Needelman, H. Examining Early Intervention Referral Patterns in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Follow up Clinics Using Telemedicine during COVID-19. Early Hum. Dev. 2022, 172, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolfi, E.; Continisio, G.I.; Del Vecchio, V.; Serra, N.; Burattini, E.; Conson, M.; Marciano, E.; Laria, C.; Franzè, A.; Caso, A.; et al. NeonaTal Assisted TelerehAbilitation (T.A.T.A. Web App) for Hearing-Impaired Children: A Family-Centered Care Model for Early Intervention in Congenital Hearing Loss. Audiol. Res. 2022, 12, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- du Plessis, D.; Mahomed-Asmail, F.; le Roux, T.; Graham, M.A.; de Kock, T.; van der Linde, J.; Swanepoel, D.W. mHealth-Supported Hearing Health Training for Early Childhood Development Practitioners: An Intervention Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, F.; Maurier, L.; Carillo, K.; Ologeanu-Taddei, R.; Septans, A.-L.; Gepner, A.; Le Goff, F.; Desbois, M.; Demurger, B.; Silber, D.; et al. Early Detection of Neurodevelopmental Disorders of Toddlers and Postnatal Depression by Mobile Health App: Observational Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e38181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.C.; Aleman-Tovar, J.; Johnston, A.N.; Little, L.M.; Burke, M.M. A Qualitative Study Exploring Parental Perceptions of Telehealth in Early Intervention. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2022, 35, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kaat, A.J.; Roberts, M.Y. Involving Caregivers of Autistic Toddlers in Early Intervention: Common Practice or Exception to the Norm? Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2022, 31, 1755–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, C.C.; Ibañez, L.V.; DesChamps, T.D.; Attar, S.M.; Stone, W.L. Brief Report: Perceptions of Family-Centered Care across Service Delivery Systems and Types of Caregiver Concerns about Their Toddlers’ Development. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 4181–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiano, A.E.; Newton, R.L.; Beyl, R.A.; Kracht, C.L.; Hendrick, C.A.; Viverito, M.; Webster, E.K. mHealth Intervention for Motor Skills: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021053362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaseca, R.; Ferrer, F.; Rivero, M.; Bersabé, R.M. Early Intervention Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: Toward a Model of Family-Centered Practices. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 738463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemes-Campana, I.-C.; Romero-Galisteo, R.-P.; Galvez-Ruiz, P.; Labajos-Manzanares, M.-T.; Moreno-Morales, N. Service Quality in Early Intervention Centres: An Analysis of Its Influence on Satisfaction and Family Quality of Life. Children 2021, 8, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ventura, S.; Mas, J.M.; Balcells-Balcells, A.; Giné, C. Family-Centred Early Intervention: Comparing Practitioners’ Actual and Desired Practices. Child. Care Health Dev. 2021, 47, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-H.; Liu, T.-W. Does Parental Education Level Matter? Dynamic Effect of Parents on Family-Centred Early Intervention for Children with Hearing Loss. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2021, 68, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.W.; Burke, M.; Isaacs, S.; Rios, K.; Schraml-Block, K.; Aleman-Tovar, J.; Tompkins, J.; Swartz, R. Family Perspectives toward Using Telehealth in Early Intervention. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2021, 33, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronberg, J.; Tierney, E.; Wallisch, A.; Little, L.M. Early Intervention Service Delivery via Telehealth During COVID-19: A Research-Practice Partnership. Int. J. Telerehabil 2021, 13, e6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.I.; Park, H.Y.; Yoo, E.; Han, A. Impact of Family-Centered Early Intervention in Infants with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Single-Subject Design. Occup. Ther. Int. 2020, 2020, 1427169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes-Scholes, C.H.; Gavidia-Payne, S. Early Childhood Intervention Program Quality: Examining Family-Centered Practice, Parental Self-Efficacy and Child and Family Outcomes. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Glazebrook, C.; Wharrad, H.; Siriwardena, A.N.; Swift, J.A.; Nathan, D.; Weng, S.F.; Atkinson, P.; Ablewhite, J.; McMaster, F.; et al. Proactive Assessment of Obesity Risk during Infancy (ProAsk): A Qualitative Study of Parents’ and Professionals’ Perspectives on an mHealth Intervention. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameyaw, G.A.; Ribera, J.; Anim-Sampong, S. Interregional Newborn Hearing Screening via Telehealth in Ghana. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2019, 30, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helle, C.; Hillesund, E.R.; Omholt, M.L.; Øverby, N.C. Early Food for Future Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the Effect of an eHealth Intervention Aiming to Promote Healthy Food Habits from Early Childhood. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; van Velthoven, M.H.; Chen, L.; Car, J.; Rudan, I.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Du, X.; Scherpbier, R.W. Text Messaging Data Collection for Monitoring an Infant Feeding Intervention Program in Rural China: Feasibility Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaiser, K.M.; Behl, D.; Callow-Heusser, C.; White, K.R. Measuring Costs and Outcomes of Tele-Intervention When Serving Families of Children Who Are Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing. Int. J. Telerehabil 2013, 5, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cason, J.; Behl, D.; Ringwalt, S. Overview of States’ Use of Telehealth for the Delivery of Early Intervention (IDEA Part C) Services. Int. J. Telerehabil 2012, 4, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schertz, H.H.; Horn, K. Facilitating Toddlers’ Social Communication from within the Parent-Child Relationship: Application of Family-Centered Early Intervention and Mediated Learning Principles. In Handbook of Parent-Implemented Interventions for Very Young Children with Autism; Siller, M., Morgan, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 141–154. ISBN 978-3-319-90994-3. [Google Scholar]

- Badawy, S.M.; Radovic, A. Digital Approaches to Remote Pediatric Health Care Delivery during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Existing Evidence and a Call for Further Research. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2020, 3, e20049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, W.-M.; Lee, P.K.C. mHealth and COVID-19: A Bibliometric Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giansanti, D. The Role of the mHealth in the Fight against the COVID-19: Successes and Failures. Healthcare 2021, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. The RIDBC Telepractice Training Protocol: A Model for Meeting ASHA Roles and Responsibilities. Perspect. Telepractice 2013, 3, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnemer, A. Benefits of Early Intervention for Children with Developmental Disabilities. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 1998, 5, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, D.; Feldman, R.; Martorell, G. Desarrollo Humano; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-607-15-0933-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J.P. Building a New Biodevelopmental Framework to Guide the Future of Early Childhood Policy. Child. Dev. 2010, 81, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federación Estatal de Asociaciones de Profesionales de Atención Temprana. Libro Blanco de La Atención Temprana; Real Patronato de Discapacidad: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J. The Person-Centered Way: Revolutionizing Quality of Life in Long-Term Care; BookSurge Publishing: South Carolina, SC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4392-4614-6. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, T. La Atención Centrada en la Persona en Los Servicios Gerontológicos: Modelos de Atención e Instrumentos de Evaluación; Universidad de Oviedo: Oviedo, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, F.A.; Escorcia, C.T.; Sánchez-López, M.C.; Orcajada, N.; Hernández-Pérez, E. Atención Temprana Centrada En La Familia. Siglo Cero 2014, 45, 6–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gine, C.; Gracia, M.; Velaseca, R.; Garcia-Die, M.T. Rethinking Early Childhood Intervention: Proposals for Future Development. Infanc. Y Aprendiz. 2006, 29, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision. The Impact of Demographic Change in a Changing Environment; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Title | Authors and Year | Country | Type of Design | Sample | Variables Studied | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Even though a lot of kids have it, not a lot of people have knowledge of it: A qualitative study exploring the perspectives of parents of children with cerebral/cortical visual impairment. | Oliver et al., 2023 [41] | USA | Mixed: qualitative and quantitative ex post facto descriptive. | Parents with children diagnosed with cortical visual impairment (CVI) | Awareness of CVI and its impact on children and family; parental experience; child factors and functional implications; supports that enhance vision development. | Need for education on the importance of early diagnosis, the clinical features of CVI and adaptations to optimize the child’s progress. This is related to more positive experiences for parents with less of a burden and frustration, and a feeling that they could actively collaborate in the process. |

| Social validity of telepractice in early intervention: Effectiveness of family-centered practices. | Martínez-Rico et al., 2023 [42] | Spain | Ex post facto cross-sectional quantitative. | 659 Spanish families from 35 EI centers. | Social validity (usability, effectiveness (competence and confidence), intervention with the caregiver, feasibility, usefulness and future interventions). | Active family participation and attention to the needs and priorities that they require are relevant factors for social validity in Spanish families in EI through tele-intervention. Other key components for this sphere of intervention that have a significant influence on the perception of families are also highlighted; collaborating to find joint solutions and promoting active participation during the sessions. |

| Diversity of Child and Family Characteristics of Children with Hearing Loss in Family-Centered Early Intervention in The Netherlands. | Van der Zee and Dirks, 2022 [43] | The Netherlands | Quantitative descriptive cross-sectional ex post facto. | Dutch children born in 2014–2016 with bilateral hearing loss who are in the FCEI program. | Socio-demographic factors, language, intervention-related factors and family involvement. | Despite having a common diagnosis, the characteristics of the children and families were very heterogeneous. Need to promote an intervention taking into account the beliefs and needs of the whole family, supporting and guiding them. The involvement of the family and the appearance of additional disabilities were predictive factors of the children’s language abilities. |

| Family-centered practices in early intervention: family confidence, competence, and quality of life. | Subinas-Medina et al., 2022 [44] | Spain | Quantitative cross-sectional ex post facto, correlational and descriptive. | 43 Spanish families of children attending the EI service. | Family quality of life; competence and confidence of families, number of practitioners, parental confidence and competence. | Families receiving EI services in Spain have a fairly good perception of FQoL, which may be related to the support of a single practitioner. The higher the confidence in parenting and parental competence, the higher the family quality of life; the confidence of primary caregivers in helping the family predicts the confidence and competence of parents in supporting the child in daily routines. |

| Assessing the Satisfaction and Acceptability of an Online Parent Coaching Intervention: A Mixed-Methods Approach. | Qu et al., 2022 [45] | China | Mixed: qualitative and randomized clinical trial. | 32 caregivers with children diagnosed with ASD aged 2–5 years old. | Acceptability, timeliness, feasibility, project-level suggestions and service-level considerations. | Positive perceptions regarding the variables of satisfaction, acceptability, suitability, feasibility and recommendation of the program. |

| Communicating With Intention: Therapist and Parent Perspectives on Family-Centered Care in Early Intervention. | Popova, O’Brien and Taylor, 2022 [21] | USA | Ex post facto cross-sectional quantitative. | 101 therapists (developmental n = 29; occupational n = 32; physical n = 17; speech n = 28) and 19 parents involved in the EI program. | Self-efficacy (professionals and parents); family-centered intervention process; therapeutic communication; suboptimal interactions; sociodemographic variables. | The family-centered model is a benchmark in pediatrics that ensures parental engagement and is associated with positive therapeutic outcomes. Therapists’ capacity for effective application of this model is limited. The Intentional Relationship Model recognizes that the interpersonal dynamic between therapist–parents–child has the power to enable or inhibit parent and child engagement in therapy. The distinction between different ways therapists communicate can implement an intervention based entirely on the family-centered model. |

| Impact of a family-centred early intervention programme in South India on children with developmental delays. | Muthukaruppan et al., 2022 [46] | India | Quantitative: Open prospective longitudinal cohort design. | 308 primary caregivers of children aged 0–6 years with developmental delay who were receiving some form of care within the study program. | Family empowerment and level of caregiver burden | The study demonstrates that early family-centered intervention, supported by digital technology to provide training and education to caregivers, has positive effects on empowerment and burden level. Change evident in all caregivers regardless of sex, age or place of therapy. |

| Relationships between family-centered practices and parent involvement in early childhood intervention. | Mas et al., 2022 [47] | Spain | Quantitative: Quasi-experimental design | 278 parents of children aged 0–6. | Socio-demographic characteristics; family-centered participatory practices; family-centered relational practices and level of participation. | Meaningful and active participation in EI has greater benefits than merely relational practices. |

| Family-Centered Early Intervention (FCEI) Involving Fathers and Mothers of Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing: Parental Involvement and Self-Efficacy. | Dirks & Szarkowski, 2022 [48] | The Netherlands | Quantitative cross-sectional post facto. | 24 Dutch couples (mother-father) with at least one child with moderate-severe hearing loss aged 0–4 years. | Self-efficacy in parenting; experience with children with hearing loss; Perceived support from family-centered EI services and Frequency of participation in family-centered EI. Family. | Although both fathers and mothers reported high levels of self-efficacy, mothers reported higher levels than fathers in some of the domains. There was a tendency for mothers to be more involved in the interventions. All this points to possible differences in terms of needs, and therefore providers should address these needs differently. |

| An mHealth Intervention to Reduce the Packing of Discretionary Foods in Children’s Lunch Boxes in Early Childhood Education and Care Services: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. | Pearson et al., 2022 [49] | Australia | Cluster randomized controlled trial. | 355 parent–child dyads for 3–6 year-olds from 17 education and EI services. | Packaging and consumption of packed lunch food; characteristics of parents and service; process evaluation. | Despite the intervention not achieving the main objective, the following data were obtained: the use of apps was rated as an adequate modality to deliver information, lack of impact associated with the implementation of the intervention, low acceptance and use of the apk by parents. |

| Examining early intervention referral patterns in neonatal intensive care unit follow-up clinics using telemedicine during COVID-19. | Miller et al., 2022 [50] | USA | Ex post facto cross-sectional quantitative. | 658 NICU follow-up visits (384 face-to-face and 274 tele-intervention). | Medical referral pattern; school referral pattern; distance travelled home-clinical centre; level of satisfaction with the service | All babies received the necessary interventions, reducing the cost and distance travelled in remote areas. Likewise, referral rates were significantly higher for medical services and the same likelihood of referral for school services. It is concluded that telemedicine saves time, money and is as effective or better at identifying the need for additional referral. |

| Neonatal-Assisted Telerehabilitation (T.A.T.A. Web App) for Hearing-Impaired Children: A Family-Centered Care Model for Early Intervention in Congenital Hearing Loss. | Landolfi et al., 2022 [51] | Italy | Quantitative longitudinal. | 15 children with deafness (240–300 days). | Socio-demographic characteristics; hearing skills; Family involvement in the intervention program. | The TATA app provides proactive management of DHH children through parental involvement. It provides a general and specific developmental profile of emerging skills and at-risk situations. Alongside this, other research has shown that this model facilitates family inclusion; essential for improving children’s language outcomes and enabling children’s continued education in their routine settings. |

| mHealth-Supported Hearing Health Training for Early Childhood Development Practitioners: An Intervention Study. | Du Plessis et al., 2022 [52] | South Africa | Experimental design. Randomized pre–post test clinical design. | 1012 practitioners aged 17–31. | Legibility of the information provided; training; knowledge post 6 months. | It is further concluded that a multimedia mHealth auditory training program is a scalable, low-cost intervention to provide professionals with the necessary knowledge to identify and refer children at risk and to support children with difficulties in the school environment. |

| Early Detection of Neurodevelopmental Disorders of Toddlers and Postnatal Depression by Mobile Health App: Observational Cross-sectional Study. | Denis et al., 2022 [53] | France | Quantitative cross-sectional. | 4000 users of the Malo apk. | Age and sex of children; neurodevelopmental skills; language, socialization, hearing, vision and motor skills; risk of postpartum depression; relevance of physician alerts and level of satisfaction. | This multi-domain apk dedicated to the early detection of NDD and PND suggests that a multi-domain family mHealth app is suitable and effective for regular use in monitoring the mother–child dyad. It should be noted that the main finding of this study is that 0.9% of small children were identified as potential ASD children at 11 months; this is very close to the ASD rate in the general population (0.6%) with a mean age of detection of 4–6.8 years. |

| A Qualitative Study Exploring Parental Perceptions of Telehealth in Early Intervention. | Cheung et al., 2022 [54] | USA | Qualitative | 15 parents of children who had received EI via telehealth (1–3a). | Parent–child socio-demographic data; Access to telehealth EI services; Practitioner–family partnerships; Training; Initial support for facilitating EI through telehealth. | Four main findings: advantages and disadvantages of accessing EI services through tele-intervention; high-quality family–practitioner partnerships preserved during sessions; need to overcome logistical barriers to accessing this modality of services; practitioners need to strengthen their knowledge and skills on how to collaborate and empower caregivers during sessions rather than carry out direct therapy on the child. |

| Involving Caregivers of Autistic Toddlers in Early Intervention: Common Practice or Exception to the Norm? | Lee et al., 2022 [55] | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional ex post facto and descriptive. | Families with children under 36 months with a diagnosis of ASD. | Socio-demographic characteristics; behaviours observed during the therapy session. | The creation of strong bonds between the practitioner who treats language disorders and the family. |

| Brief Report: Perceptions of Family-Centered Care Across Service Delivery Systems and Types of Caregiver Concerns About Their Toddlers’ Development. | Dick et al., 2022 [56] | USA | Part of a longitudinal study. | Family members of children with ASD 16–33 months (n = 37); family members of children with other neurodevelopmental disorders (n = 22). | Socio-demographic data; measurement of the care process distinguishing between primary and early intervention services. | Caregivers perceive higher levels of family-centered care from early intervention professionals than from primary care professionals. The importance of both teams working continuously during the detection, diagnosis and intervention processes is underlined. |

| mHealth Intervention for Motor Skills: A Randomized Controlled Trial. | Staiano et al., 2022 [57] | USA | Randomized controlled study. | n = 72 children (3–5 years); 35 motor skills app and 37 free play app. | Motor skills; degree of acceptability and adherence. | The use of the motor skills apk led to an increase in the motor skills percentile. Likewise, there were also improvements in motor skills that were not covered by the apk, indicating a transfer of learning to more global aspects. High levels of adherence and acceptability were recorded in both applications. |

| Early Intervention Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: Toward a Model of Family-Centered Practices. | Vilaseca et al., 2021 [58] | Spain | Ex post facto cross-sectional quantitative. | Sub-sample 1.—81 families of children cared for in EI (0–6); Sub-sample 2.—213 professionals working in EI. | Perception of families on the change in intervention methodology after the pandemic; Perception of professionals on the changes in intervention methodology with families and children after the pandemic; Socio-demographic variables. | The change in methodology did not present significant changes in terms of incorporating the family-centered model. Professionals considered that the intervention followed the trends of this model, but the results of the families were inconclusive, reflecting the difficulty of application with respect to socio-demographic variables. |

| Service Quality in Early Intervention Centres: An Analysis of Its Influence on Satisfaction and Family Quality of Life. | Jemes-Campaña et al., 2021 [59] | Spain | Ex post facto cross-sectional quantitative. | 1551 parents of children attending one of the 24 EI centers in Andalusia participating in the study with developmental problems or at risk of developmental problems. | Degree of satisfaction with the service; Perceived quality of the service; Family quality of life. | Perceived quality and satisfaction with EI centers are tools for achieving family quality of life. There are relationships between these aspects, which, together with the degree of support received by families from professionals, influence quality of life. |

| Family-centered early intervention: Comparing practitioners’ actual and desired practices. | García-Ventura et al., 2021 [60] | Spain | Ex post facto cross-sectional quantitative. | 119 Spanish EI practitioners whose projects based on the family-centered model were in the early stages. | Practitioner characteristics; Current and desired practices. | There is a desire to move towards the family-centered model in current practices on the part of practitioners, but there are also barriers to this that are not dependent on the practitioner. Likewise, no correlation is found between years of experience or level of university studies with FOCAS results. |

| Does Parental Education Level Matter? Dynamic Effect of Parents on Family-Centered Early Intervention for Children with Hearing Loss. | Chen & Liu, 2021 [61] | Taiwan | Mixed: Path Analysis. | 113 children 3–6 years old with permanent bilateral hearing loss attending auditory–verbal therapy in an EI centre in Taiwan. | Language skills (language comprehension and speech); time in hearing therapy; age at which hearing aids are used and parents’ educational levels. | The role of parents has clinical implications for language comprehension in children with hearing loss, meaning that cooperation with both parents is key. Similarly, social disadvantages between caregiver and child could be reduced through early intervention. |

| Family Perspectives toward Using Telehealth in Early Intervention. | Yang et al., 2021 [62] | USA | Qualitative. | 37 parents with at least one child aged 0–9 who has received EI assistance. | Socio-demographic data; Family perceptions on the use of telehealth; Family perceptions on the advantages of telehealth; Family perceptions on the disadvantages of telehealth; Family perceptions on logistical elements needed to implement telehealth-based care. | Participants were reluctant to use telehealth in EI. The possible explanation could be misconceptions about the aims and purposes of EI as well as logistical barriers to accessing services and materials. |

| Practitioners’ Self-Assessment of Family-Centered Practice in Telepractice Versus In-Person Early Intervention. | McCarthy et al., 2021 [20] | Australia | Ex post facto cross-sectional quantitative. | 52 early intervention professionals and 239 children under 8 years old. | Socio-demographic data; rating of care processes for service providers (MPOC-SP). | Practitioners who worked via telepractice reported using family-centered practices to a similar degree as those who intervened face to face. Analyses of the MPOC-SP scale indicated that there were no significant relationships between practitioners’ assessment of their use of family-centered practices and mode of intervention; results were consistent even with other more specific variables such as type of practitioner, experience, etc. |

| Early intervention service delivery via telehealth during COVID-19: a research–practice partnership. | Kronberg et al., 2021 [63] | USA | Quasi-experimental design with pre–post measures. | 17 families enrolled in the state EI program aged 6–34 months. | Socio-demographic data; progress towards achieving the family’s goals; Goal performance and degree of satisfaction. | The findings suggest that a 9-week coaching intervention provided through telehealth by community-based specialist EI practitioners can be effective in promoting parents’ goals and satisfaction motivated by their children’s achievements. |

| Impact of Family-Centered Early Intervention in Infants with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Single-Subject Design. | Park et al., 2020 [64] | Republic of Korea | Case study. | 3 children aged between 2 and 3 years with suspected ASD. | Interventions based on the family-centered model of care (environmental modifications, video recording, task training and feedback, individualized information on the child and task completion rate); Frequency of social interactions during the interventions; changes in social interaction skills; changes in ASD risk. | After implementing the family-centered early intervention program, all participants improve significantly during and after the intervention in the three modes of social interaction skills (appearance, gestures and speech). The ASD risk score decreased significantly. Similarly, parents’ performance improved and, with it, their internal motivation. |

| Early Childhood Intervention Program Quality: Examining Family-Centered Practice, Parental Self-Efficacy and Child and Family Outcomes. | Hughes-Scholes & Gavidia-Payne, 2019 [65] | Australia | Clinical trial with pre–post measures. | 66 families with children with developmental problems (average age 46 months). | Socio-demographic characteristics; family outcomes; parental self-efficacy and perceptions of practices before and after the intervention. | There is an improvement in both child and parents’ skills following participation in the family-centered EI program, although no direct links can be made between this improvement and the model itself. |

| Proactive Assessment of Obesity Risk during Infancy (ProAsk): a qualitative study of parents’ and professionals’ perspectives on an mHealth intervention. | Rose et al., 2019 [66] | United Kingdom | Qualitative. | 66 families of children aged 6–8 weeks and 22 health visitors. | Participation and empowerment with digital technology; Unfamiliar technology presents challenges and opportunities; Confidence in risk scoring; Resistance to targeting. | The intervention based on the mHealth model actively involved parents, allowing them to take ownership of the process of finding strategies to reduce the risk of childhood overweight. Cognitive and motivational biases were detected that prevented effective communication on the central theme, causing barriers in the intervention of those infants most at risk. |

| Interregional Newborn Hearing Screening via Telehealth in Ghana. | Ameyaw, Ribera & Anim-Sampong, 2019 [67] | Ghana | Non-randomized cross-sectional quantitative | 50 nursing infants aged 2–90 days (convenience sample; 30 males and 20 females). | Traditional screening procedure, virtual screening procedure, duration of both procedures. | The study shows the possible feasibility of establishing an interregional network of newborn hearing screening services in Ghana using telehealth, demonstrating high efficiency rates when comparing the use of these services with the mobility of these families to receive similar services. |

| Early food for future health: a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of an eHealth intervention aiming to promote healthy food habits from early childhood. | Helle et al., 2017 [68] | Norway | Randomized controlled study. | 718 Norwegian parents with a full-term child of 3–5 months of age with a birth weight ≥ 2500 g. | In children: anthropometric measures; food intakes; food variation; child’s eating behaviour; child temperament, food preferences; child behavior. In parents: socio-demographic characteristics; anthropometric measures; food intake; food variation; food neophobia; feeding style and feeding practices; feeding self-efficacy; parenting style; personality traits and mental health. | The Early Food for Future Health eHealth intervention guides parents of children aged 6–12 months through the different developmental stages related to feeding. Its use can increase awareness and understanding of the importance of preventing childhood overweight and obesity in terms of: design and effectiveness of internet-based interventions and the relationship between parenting, feeding behavior in parents and children. |

| Text messaging data collection for monitoring an infant feeding intervention program in rural China: feasibility study. | Li et al., 2013 [69] | China | Quantitative with pre–post measures non-randomized. | 258 participants (n = 99; text messaging respondents vs. n = 177 face-to-face respondents). | Response rate; Data agreement; Costs; Acceptability of text messages and face-to-face surveys; Reasons for not responding to text messages; Reasons for disagreement between survey methods; Adequate moment to send text messages. | The feasibility of using text messaging as a method of data collection for monitoring health programs in rural China was studied. Although the text message survey was acceptable and there was a reduction in costs, it had a lower response rate. Future research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies to increase the response rate, especially in terms of longitudinal data collection. |

| Measuring Costs and Outcomes of Tele-Intervention When Serving Families of Children who are Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing. | Blaiser et al., 2013 [70] | USA | Randomized controlled trial. | 27 families enrolled in the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind (USDB) Parent Infant Program (PIP). | Receptive and expressive language skills; costs; quality of the home visit; perceptions of carers and providers. | One of the reasons why some families did not want to participate is that the use of tele-intervention implied an additional effort associated with learning an NT that was not desirable or feasible at that time. This aspect to which participants were subjected during the first months of the study influenced the satisfaction scores. Another aspect to keep in mind is that satisfaction improved dramatically when connection problems were solved; for the implementation of these services, access to sufficient bandwidth is necessary, which translates into upload and download speed. |

| Overview of States’ Use of Telehealth for the Delivery of Early Intervention (IDEA Part C) Services. | Cason et al., 2012 [71] | USA | Quantitative ex post facto. | Representatives from 26 states and one IDEA Part C jurisdiction. | Early telehealth intervention providers; telehealth reimbursement within early intervention; barriers to telehealth implementation. | Many states are incorporating telehealth into their care programs under the Early Intervention for Individuals with Disabilities Education Act to improve service quality. Practitioners under the Act are already using telehealth services to provide habilitation services and specialized consultations (IDEA). Policy development, education, research, the use of secure applications and the promotion of strategies are important in order to qualify telehealth as a service model within IDEA Part C programs. |

| Authors and Year | Level of Evidence | Grade of Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Oliver et al. (2023) [41] | 2++ | B |

| Martínez-Rico et al. (2023) [42] | 2++ | B |

| Van der Zee & Dirks (2022) [43] | 2++ | B |

| Subinas-Medina et al. (2022) [44] | 2++ | B |

| Qu et al. (2022) [45] | 1++ | A |

| Popova et al. (2022) [21] | 2++ | B |

| Muthukaruppan et al. (2022) [46] | 2+ | C |

| Mas et al. (2022) [47] | 2++ | B |

| Dirks & Szarkowski (2022) [48] | 2+ | C |

| Pearson et al. (2022) [49] | 1++ | A |

| Miller et al. (2022) [50] | 2++ | B |

| Landolfi et al. (2022) [51] | 2+ | C |

| Du Plessis et al. (2022) [52] | 1++ | A |

| Denis et al. (2022) [53] | 2++ | B |

| Cheung et al. (2022) [54] | 2− | C |

| Lee et al. (2022) [55] | 2++ | B |

| Dick et al. (2022) [56] | 2++ | B |

| Staiano et al. (2022) [57] | 1++ | A |

| Vilaseca et al. (2021) [58] | 2++ | B |

| Jemes-Campaña et al. (2021) [59] | 2++ | B |

| García-Ventura et al. (2021) [60] | 2++ | B |

| Chen & Liu (2021) [61] | 1+ | A |

| Yang et al. (2021) [62] | 2+ | C |

| McCarthy et al. (2021) [20] | 2++ | B |

| Kronberg et al. (2021) [63] | 2+ | C |

| Park et al. (2020) [64] | 2- | C |

| Hughes-Scholes & Gavidia-Payne (2019) [65] | 2+ | C |

| Rose et al. (2019) [66] | 2+ | C |

| Ameya et al. (2019) [67] | 1++ | A |

| Helle et al. (2017) [68] | 1++ | A |

| Li et al. (2013) [69] | 2+ | C |

| Blaiser et al. (2013) [70] | 1++ | A |

| Cason et al. (2012) [71] | 2++ | B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jimenez-Arberas, E.; Casais-Suarez, Y.; Fernandez-Mendez, A.; Menendez-Espina, S.; Rodriguez-Menendez, S.; Llosa, J.A.; Prieto-Saborit, J.A. Evidence-Based Implementation of the Family-Centered Model and the Use of Tele-Intervention in Early Childhood Services: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010112

Jimenez-Arberas E, Casais-Suarez Y, Fernandez-Mendez A, Menendez-Espina S, Rodriguez-Menendez S, Llosa JA, Prieto-Saborit JA. Evidence-Based Implementation of the Family-Centered Model and the Use of Tele-Intervention in Early Childhood Services: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(1):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010112

Chicago/Turabian StyleJimenez-Arberas, Estibaliz, Yara Casais-Suarez, Alba Fernandez-Mendez, Sara Menendez-Espina, Sergio Rodriguez-Menendez, Jose Antonio Llosa, and Jose Antonio Prieto-Saborit. 2024. "Evidence-Based Implementation of the Family-Centered Model and the Use of Tele-Intervention in Early Childhood Services: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 12, no. 1: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010112

APA StyleJimenez-Arberas, E., Casais-Suarez, Y., Fernandez-Mendez, A., Menendez-Espina, S., Rodriguez-Menendez, S., Llosa, J. A., & Prieto-Saborit, J. A. (2024). Evidence-Based Implementation of the Family-Centered Model and the Use of Tele-Intervention in Early Childhood Services: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 12(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010112

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)