Effectiveness of Self-Affirmation Interventions in Educational Settings: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Assessment of the Methodological Quality

2.4. Data Extraction and Data Items

2.5. Calculation of Effect Sizes

2.6. Meta-Analysis Strategy

3. Results

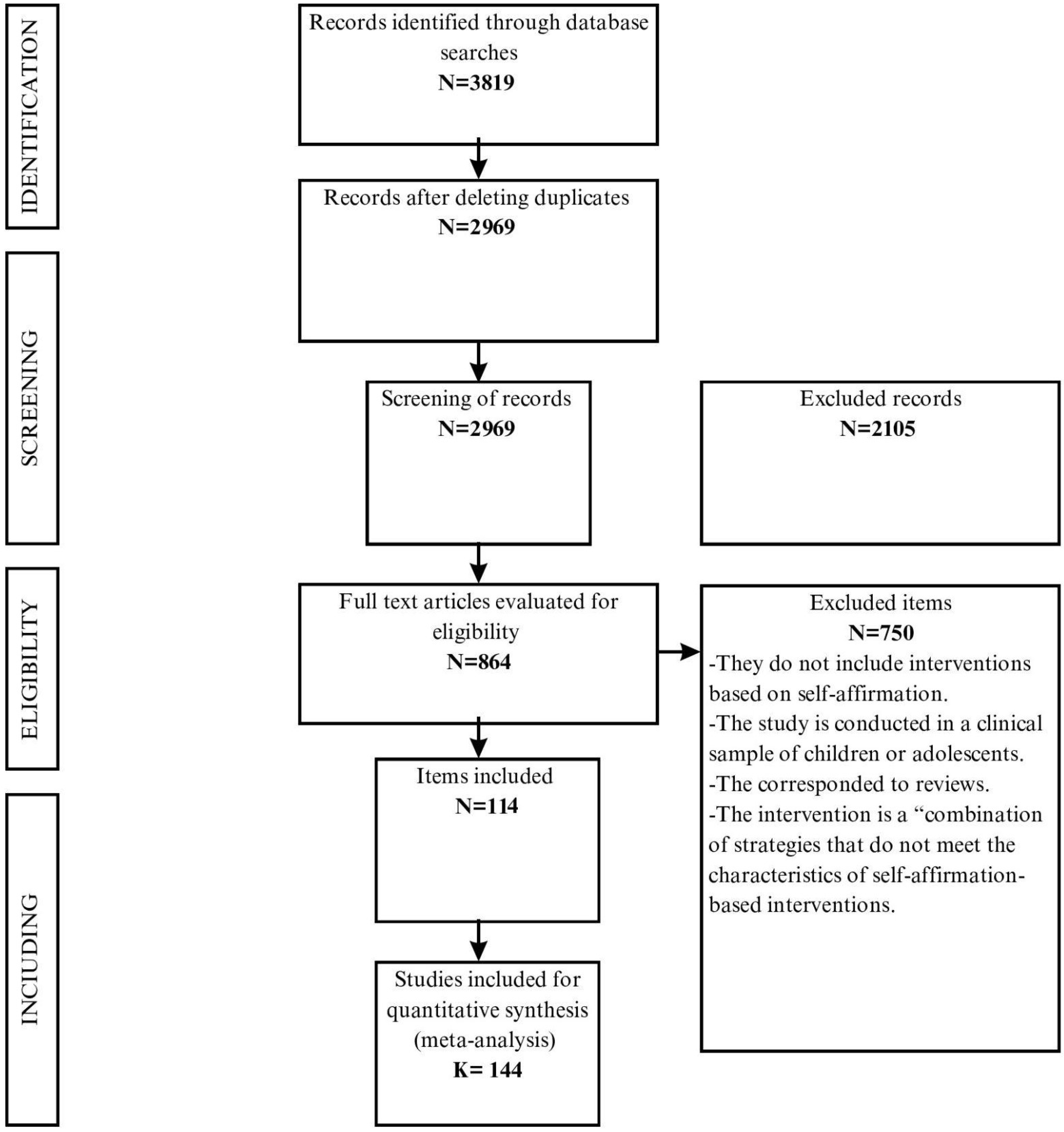

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Main Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Assessment of Methodological Quality

3.4. Magnitude of Effectiveness

3.5. Moderators of Effectiveness

3.6. Publication Biases

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia, T.; Pintrich, P.R. Regulating motivation and cognition in the classroom: The role of self-schemas and self-regulatory strategies. In Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance: Issues and Educational Applications; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham, S.; Ogbu, J.U. Black students’ school success: Coping with the “burden of acting White”. Urban Rev. 1986, 18, 176–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 21: Social Psychological Studies of the Self: Perspectives and Programs; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Major, B.; Spencer, S.; Schmader, T.; Wolfe, C.; Crocker, J. Coping with negative stereotypes about intellectual performance: The role of psychological disengagement. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.; Fried, C.B.; Good, C. Reducing the Effects of Stereotype Threat on African American College Students by Shaping Theories of Intelligence. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratter, J.L.; Rowley, K.J.; Chukhray, I. Does a self-affirmation intervention reduce stereotype threat in black and hispanic high schools? Race Soc. Probl. 2016, 8, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, N.K.; Wegmann, K.M.; Webber, K.C. Enhancing a brief writing intervention to combat stereotype threat among middle-school students. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.L.; Garcia, J.; Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Apfel, N.; Brzustoski, P. Recursive Processes in Self-Affirmation: Intervening to Close the Minority Achievement Gap. Science 2009, 324, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.E.; Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Garcia, J.; Cohen, G.L. Chronic threat and contingent belonging: Protective benefits of values affirmation on identity development. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.K.; Hartson, K.A.; Binning, K.R.; Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Garcia, J.; Taborsky-Barba, S.; Tomassetti, S.; Nussbaum, A.D.; Cohen, G.L. Deflecting the trajectory and changing the narrative: How self-affirmation affects academic performance and motivation under identity threat. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 591–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critcher, C.R.; Dunning, D.; Armor, D.A. When self-affirmations reduce defensiveness: Timing is key. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Measuring and improving school climate: A pro-social strategy that recognizes, educates, and supports the whole child and the whole school community. In The Handbook of Prosocial Education; Brown, P.M., Corrigian, M.W., Higgins, D.A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shnabel, N.; Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Cook, J.E.; Garcia, J.; Cohen, G.L. Demystifying values-affirmation interventions: Writing about social belonging is a key to buffering against identity threat. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, D.S.; Walton, G.M. Social-Psychological Interventions in Education: They’re Not Magic. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 267–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G.D.; Pyne, J. What If Coleman Had Known About Stereotype Threat? How Social-Psychological Theory Can Help Mitigate Educational Inequality. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 164–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G.D. Advancing values affirmation as a scalable strategy for mitigating identity threats and narrowing national achievement gaps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7486–7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.L.; Garcia, J.; Apfel, N.; Master, A. Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-psychological intervention. Science 2006, 313, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzlicht, M.; Schmader, T. Stereotype Threat: Theory, Process, and Application; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, C.M.; Spencer, S.J.; Aronson, J. Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; Volume 34, pp. 379–440. [Google Scholar]

- Hanselman, P.; Bruch, S.K.; Gamoran, A.; Borman, G.D. Threat in context: School moderation of the impact of social identity threat on racial/ethnic achievement gaps. Sociol. Educ. 2014, 87, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmader, T.; Johns, M.; Forbes, C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 115, 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, A.; Johns, M.; Greenberg, J.; Schimel, J. Combating stereotype threat: The effect of self-affirmation on women’s intellectual performance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 42, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V.J.; Walton, G.M. Stereotype threat undermines academic learning. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harackiewicz, J.M.; Tibbetts, Y.; Canning, E.; Hyde, J.S. Harnessing Values to Promote Motivation in Education. Adv. Motiv. Achiev. 2014, 18, 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, A.; Kost-Smith, L.E.; Finkelstein, N.D.; Pollock, S.J.; Cohen, G.L.; Ito, T.A. Reducing the Gender Achievement Gap in College Science: A Classroom Study of Values Affirmation. Science 2010, 330, 1234–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, B.P.; Arroyo, I.; Muldner, K.; Burleson, W.; Cooper, D.G.; Dolan, R.; Christopherson, R.M. The Effect of Motivational Learning Companions on Low Achieving Students and Students with Disabilities. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, K.; McManus, I.C.; Gill, D.; Dacre, J. The effect of a brief social intervention on the examination results of UK medical students: A cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2009, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harackiewicz, J.M.; Priniski, S.J. Improving Student Outcomes in Higher Education: The Science of Targeted Intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critcher, C.R.; Dunning, D. Self-affirmations provide a broader perspective on self-threat. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 41, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Cohen, G.L.; García, J.A.; Sumner, R.; Cook, J.; Apfel, N.H. Improving Minority Academic Performance: How a Values-Affirmation Intervention Works. Teachers College Record 2010. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:157797471 (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Brady, S.T.; Reeves, S.L.; Garcia, J.; Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Cook, J.E.; Taborsky-Barba, S.; Tomasetti, S.; Davis, E.M.; Cohen, G.L. The psychology of the affirmed learner: Spontaneous self-affirmation in the face of stress. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanselman, P.; Rozek, C.S.; Grigg, J.; Borman, G.D. New Evidence on Self-Affirmation Effects and Theorized Sources of Heterogeneity from Large-Scale Replications. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 109, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.L.; Sherman, D.K. The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 333–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.B.; DeShon, R.P. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W. Random effects models. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 301–321. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. The Combination of Estimates from Different Experiments. Biometrics 1954, 10, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadish, W.R.; Haddock, C.K. Combining estimates of effect size. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 261–281. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.B. Wilson’s Meta-Analysis Page. Available online: http://mason.gmu.edu/~dwilsonb/ (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Thomaes, S.; Bushman, B.J.; de Castro, B.O.; Reijntjes, A. Arousing “gentle passions” in young adolescents: Sustained experimental effects of value affirmations on prosocial feelings and behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaes, S.; Bushman, B.J.; Orobio de Castro, B.; Cohen, G.L.; Denissen, J.J. Reducing narcissistic aggression by buttressing self-esteem: An experimental field study. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, C.J. Evidence that self-affirmation reduces body dissatisfaction by basing self-esteem on domains other than body weight and shape. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokhande, M.; Müller, T. Double jeopardy—Double remedy? The effectiveness of self-affirmation for improving doubly disadvantaged students’ mathematical performance. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 75, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binning, K.R.; Cook, J.E.; Purdie-Greenaway, V.; Garcia, J.; Chen, S.; Apfel, N.; Sherman, D.K.; Cohen, G.L. Bolstering trust and reducing discipline incidents at a diverse middle school: How self-affirmation affects behavioral conduct during the transition to adolescence. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 75, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Kurtz-Costes, B. Promoting science motivation in American Indian middle school students: An intervention. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Huang, P.-S. Beneficial effects of self-affirmation on motivation and performance reduced in students hungry for others’ approval. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Skinner, B.T.; Redding, C.H. Affirmative Intervention to Reduce Stereotype Threat Bias: Experimental Evidence from a Community College. J. High. Educ. 2020, 91, 722–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayly, B.L.; Bumpus, M.F. An exploration of engagement and effectiveness of an online values affirmation. Educ. Res. Eval. 2019, 25, 248–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, H.; Gerrard, M.; McClive-Reed, K.P. Threading the needle in health-risk communication: Increasing vulnerability salience while promoting self-worth. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.; Epton, T.; Norman, P.; Sheeran, P.; Harris, P.R.; Webb, T.L.; Julious, S.A.; Brennan, A.; Thomas, C.; Petroczi, A.; et al. A theory-based online health behaviour intervention for new university students (U@Uni:LifeGuide): Results from a repeat randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015, 16, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.; Jessop, D.C.; Goodwin, S.; Ritchie, L.; Harris, P.R. Self-affirmation improves music performance among performers high on the impulsivity dimension of sensation seeking. Psychol. Music 2018, 46, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, M.; Michel, C.; Remy, S.; Galand, B. Providing freshmen with a good “starting-block”: Two brief social-psychological interventions to promote early adjustment to the first year at university. Swiss J. Psychol. 2019, 78, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, R.; Herrmann, S.D.; Fryberg, S.A. Affirming the interdependent self: Implications for Latino student performance. Basic. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, P.J.; Sherman, D.K. Integrating Self-Affirmation and Implementation Intentions: Effects on College Student Drinking. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epton, T.; Norman, P.; Dadzie, A.S.; Harris, P.R.; Webb, T.L.; Sheeran, P.; Julious, S.A.; Ciravegna, F.; Brennan, A.; Meier, P.S.; et al. A theory-based online health behaviour intervention for new university students (U@Uni): Results from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyer, J.P.; Garcia, J.; Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Binning, K.R.; Cook, J.E.; Reeves, S.L.; Apfel, N.; Taborsky-Barba, S.; Sherman, D.K.; Cohen, G.L. Self-affirmation facilitates minority middle schoolers’ progress along college trajectories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7594–7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, W.E.; Glazer, J.V.; Berenson, K.R. Self-compassion, self-injury, and pain. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2017, 41, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, J.M.; Canning, E.A.; Tibbetts, Y.; Priniski, S.J.; Hyde, J.S. Closing achievement gaps with a utility-value intervention: Disentangling race and social class. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 111, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.; Rana, S.; Rao, A.; Usselman, M. Dismantling Stereotypes About Latinos in STEM. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2017, 39, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.O.; Huey, S.J. Affirmation and Majority Students: Does Affirmation Impair Academic Performance in White Males? Basic. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 42, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordt, H.; Eddy, S.L.; Brazil, R.; Lau, I.; Mann, C.; Brownell, S.E.; King, K.; Freeman, S. Values Affirmation Intervention Reduces Achievement Gap between Underrepresented Minority and White Students in Introductory Biology Classes. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, ar41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.K.; Place, H.; Barton, J.A.; Linke, S.; Curran, H.V.; Harris, P.R. Processing of Alcohol-Related Health Threat in At-Risk Drinkers: An Online Study of Gender-Related Self-Affirmation Effects. Alcohol. Alcohol. 2016, 51, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Niederdeppe, J. Effects of Self-Affirmation, Narratives, and Informational Messages in Reducing Unrealistic Optimism About Alcohol-Related Problems Among College Students. Human. Commun. Res. 2016, 42, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannin, D.G.; Guyll, M.; Vogel, D.L.; Madon, S. Reducing the stigma associated with seeking psychotherapy through self-affirmation. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannin, D.G.; Vogel, D.L.; Kahn, J.H.; Brenner, R.E.; Heath, P.J.; Guyll, M. A multi-wave test of self-affirmation versus emotionally expressive writing. Couns. Psychol. Q 2020, 33, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layous, K.; Davis, E.M.; Garcia, J.; Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Cook, J.E.; Cohen, G.L. Feeling left out, but affirmed: Protecting against the negative effects of low belonging in college. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 69, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, E.; Miller, M.B.; Lechner, W.V.; Lombardi, N.; Claborn, K.R.; Leffingwell, T.R. The Inability of Self-affirmations to Decrease Defensive Bias Toward an Alcohol-Related Risk Message Among High-Risk College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2015, 63, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Norman, P.; Wrona-Clarke, A. Combining self-affirmation and implementation intentions to reduce heavy episodic drinking in university students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016, 30, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, P.; Cameron, D.; Epton, T.; Webb, T.L.; Harris, P.R.; Millings, A.; Sheeran, P. A randomized controlled trial of a brief online intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in new university students: Combining self-affirmation, theory of planned behaviour messages, and implementation intentions. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Shoots-Reinhard, B.; Tompkins, M.K.; Schley, D.; Meilleur, L.; Sinayev, A.; Tusler, M.; Wagner, L.; Crocker, J. Improving numeracy through values affirmation enhances decision and STEM outcomes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, C.E.; Gregorio-Pascual, P.; Driver, R.; Martinez, A.; Price, S.L.; Lopez, C.; Mahler, H.I.M. Effects of Social Norms Information and Self-Affirmation on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption Intentions and Behaviors. Basic. Appl. Soc. Psych. 2017, 39, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereno, K.; Walter, N.; Brooks, J.J. Rethinking student participation in the college classroom: Can commitment and self-affirmation enhance oral participation? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 50, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.R.; Williams, A.M.; Hambarchyan, M. Are all interventions created equal? A multi-threat approach to tailoring stereotype threat interventions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbetts, Y.; Harackiewicz, J.M.; Canning, E.A.; Boston, J.S.; Priniski, S.J.; Hyde, J.S. Affirming independence: Exploring mechanisms underlying a values affirmation intervention for first-generation students. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 110, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G.M.; Logel, C.; Peach, J.M.; Spencer, S.J.; Zanna, M.P. Two brief interventions to mitigate a “chilly climate” transform women’s experience, relationships, and achievement in engineering. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 107, 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.; Tormala, T.T.; O’Brien, L.T. The effect of self-affirmation on perception of racism. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 42, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E.; Gallardo, I.; DeMarree, K.G. The effect of self-affirmation in nonthreatening persuasion domains: Timing affects the process. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 1533–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, J.; Spencer, S.J.; Zanna, M.P. An affirmed self and an open mind: Self-affirmation and sensitivity to argument strength. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 40, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.D.; Dutcher, J.M.; Klein, W.M.P.; Harris, P.R.; Levine, J.M. Self-Affirmation Improves Problem-Solving under Stress. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Niiya, Y.; Mischkowski, D. Why does writing about important values reduce defensiveness? Self-affirmation and the role of positive other-directed feelings. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, A.J.; McCaul, K.D.; Magnan, R.E. Why Is Such a Smart Person Like You Smoking? Using Self-Affirmation to Reduce Defensiveness to Cigarette Warning Labels. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2005, 10, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epton, T.; Harris, P.R. Self-affirmation promotes health behavior change. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.R.; Napper, L. Self-affirmation and the biased processing of threatening health-risk information. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1250–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.R.; Mayle, K.; Mabbott, L.; Napper, L. Self-affirmation reduces smokers’ defensiveness to graphic on-pack cigarette warning labels. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, W.M.P.; Harris, P.R.; Ferrer, R.A.; Zajac, L.E. Feelings of vulnerability in response to threatening messages: Effects of self-affirmation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, W.M.; Harris, P.R. Self-affirmation enhances attentional bias toward threatening components of a persuasive message. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, S.L.; van Knippenberg, A. Controlling your mind without ironic consequences: Self-affirmation eliminates rebound effects after thought suppression. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, S.L.; Smeets, K.; van Knippenberg, A.; Dijksterhuis, A. The cessation of rumination through self-affirmation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L.; Al-Khindi, T.; Inzlicht, M. Preserving integrity in the face of performance threat: Self-affirmation enhances neurophysiological responsiveness to errors. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.B.; Aspinwall, L.G. Self-affirmation reduces biased processing of health-risk information. Motiv. Emot. 1998, 22, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.; Arndt, J.; Banko, K.M.; Cook, A. Not all self- affirmations were created equal: The cognitive and social benefit of affirming the intrinsic (vs extrinsic) self. Soc. Cogn. 2004, 22, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeichel, B.J.; Martens, A. Self-affirmation and mortality salience: Affirming values reduces worldview defense and death-thought accessibility. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeichel, B.J.; Vohs, K. Self-affirmation and self-control: Affirming core values counteracts ego depletion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.K.; Bunyan, D.P.; Creswell, J.D.; Jaremka, L.M. Psychological vulnerability and stress: The effects of self-affirmation on sympathetic nervous system responses to naturalistic stressors. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.A.K.; Nelson, L.D.; Steele, C.M. Do messages about health risks threaten the self? Increasing the acceptance of threatening health messages via self-affirmation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrira, I.; Martin, L.L. Stereotyping, Self-Affirmation, and the Cerebral Hemispheres. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanathan, N.; Molden, D.C.; Galinsky, A.D.; Ku, G. The promise and peril of self-affirmation in de-escalation of commitment. Organ. Behav. Human. Decis. Process. 2008, 107, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.J.; Fein, S.; Lomore, C.D. Maintaining one’s self-image vis-à-vis others: The role of self-affirmation in the social evaluation of the self. Motiv. Emot. 2001, 25, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.; Whitehead, J.; Schmader, T.; Focella, E. Thanks for asking: Self-affirming questions reduce backlash when stigmatized targets confront prejudice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Koningsbruggen, G.M.; Das, E.; Roskos-Ewoldsen, D.R. How self-affirmation reduces defensive processing of threatening health information: Evidence at the implicit level. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohs, K.D.; Park, J.K.; Schmeichel, B.J. Self-affirmation can enable goal disengagement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakslak, C.J.; Trope, Y. Cognitive consequences of affirming the self: The relationship between self-affirmation and object construal. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate, M.A.; Garza, A.A. In-Group Distinctiveness and Self-Affirmation as Dual Components of Prejudice Reduction. Self Identity 2002, 1, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Peterson, E.B.; Kim, W.; Rolfe-Redding, J. Effects of Self-Affirmation on Daily Versus Occasional Smokers’ Responses to Graphic Warning Labels. Commun. Res. 2014, 41, 1137–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero-Rejon, C.; Attwood, A.S.; Blackwell, A.K.M.; Ibáñez-Zapata, J.-A.; Munafò, M.R.; Maynard, O.M. Alcohol pictorial health warning labels: The impact of self-affirmation and health warning severity. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauketat, J.V.T.; Moons, W.G.; Chen, J.M.; Mackie, D.M.; Sherman, D.K. Self-affirmation and affective forecasting: Affirmation reduces the anticipated impact of negative events. Motiv. Emot. 2016, 40, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Yang, J.; Yang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Wu, M.; Cai, H. Self-affirmation enhances the processing of uncertainty: An event-related potential study. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 19, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillandier-Schmitt, A.; Esnard, C.; Mokounkolo, R. Self-affirmation in occupational training: Effects on the math performance of French women nurses under stereotype threat. Sex. Roles A J. Res. 2012, 67, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G.D.; Grigg, J.; Rozek, C.S.; Hanselman, P.; Dewey, N.A. Self-affirmation effects are produced by school context, student engagement with the intervention, and time: Lessons from a district-wide implementation. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G.D.; Choi, Y.; Hall, G.J. The impacts of a brief middle-school self-affirmation intervention help propel African American and Latino students through high school. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Garcia, M.; Hansen, K.T.; Gneezy, U. Can Short Psychological Interventions Affect Educational Performance? Revisiting the Effect of Self-Affirmation Interventions. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, L.J.; Zinner, L.R.; Wise, J.C.; Carton, J.S. Effects of a Self-Affirmation Intervention on Grades in Middle School and First-Year College Students. J. Artic. Support. Null. Hypothesis 2019, 16, 58–79. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:211142201 (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Hadden, I.R.; Easterbrook, M.J.; Nieuwenhuis, M.; Fox, K.J.; Dolan, P. Self-affirmation reduces the socioeconomic attainment gap in schools in England. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 90, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.L.; Brown, A.C.; Phair, J.K.; Westland, J.N.; Schüz, B. Self-affirmation, intentions and alcohol consumption in students: A randomized exploratory trial. Alcohol. Alcohol. 2013, 48, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S.P.; Wages, J.E., 3rd; Skinner-Dorkenoo, A.L.; Burke, S.E.; Hardeman, R.R.; Phelan, S.M. Testing a Self-Affirmation Intervention for Improving the Psychosocial Health of Black and White Medical Students in the US. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 77, 769–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, T.S. Social Identity and Achievement Gaps: Evidence From an Affirmation Intervention. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 2015, 8, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protzko, J.; Aronson, J. Context Moderates Affirmation Effects on the Ethnic Achievement Gap. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2016, 7, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, R.; Norman, P. Impact of brief self-affirmation manipulations on university students’ reactions to risk information about binge drinking. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kehle, T.J.; Bray, M.A.; Trudel, S.M.; Fitzmaurice, B.; Bray, A.; Del Campo, M.; DeMaio, E. Using self-affirmations to improve achievement in fourth-grade students. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 15388–15402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, K.R.; Phillips, L.A.; Green, Z.; Mentzou, A. Examining self-affirmation as a tactic for recruiting inactive women into exercise interventions. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2022, 14, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.N.; Rozek, C.S.; Manke, K.J.; Dweck, C.S.; Walton, G.M. Teacher- versus researcher-provided affirmation effects on students’ task engagement and positive perceptions of teachers. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 77, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Brockner, J.; Block, C.J. Tailoring the intervention to the self: Congruence between self-affirmation and self-construal mitigates the gender gap in quantitative performance. Organ. Behav. Human. Decis. Process. 2022, 169, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Tiwari, G.K.; Rai, P.K. Restoring and preserving capacity of self-affirmation for well-being in Indian adults with non-clinical depressive tendencies. Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 2021, 9, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeste, L.; Baysu, G.; Phalet, K.; Brown, R. Self-affirmation and test performance in ethnically diverse schools: A new dual-identity affirmation intervention. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 77, 824–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Archer Lee, Y.; Krampitz, E.; Lin, X.; Atilla, G.; Nguyen, K.C.; Rosen, H.R.; Tham, C.Z.E.; Chen, F.S. Computer passwords as a timely booster for writing-based psychological interventions. Internet Interv. 2022, 30, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G.D.; Pyne, J.; Rozek, C.S.; Schmidt, A. A Replicable Identity-Based Intervention Reduces the Black-White Suspension Gap at Scale. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 59, 284–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binning, K.R.; Cook, J.E.; Greenaway, V.P.; Garcia, J.; Apfel, N.; Sherman, D.K.; Cohen, G.L. Securing self-integrity over time: Self-affirmation disrupts a negative cycle between psychological threat and academic performance. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 77, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilot, I.G.; Stutts, L.A. The impact of a values affirmation intervention on body dissatisfaction and negative mood in women exposed to fitspiration. Body Image 2023, 44, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, S.M.; Myre, M.; Berry, T.R.; Ceccarelli, L.A.; Semenchuk, B.N.; Miller, C. Self-affirmation and physical activity messages. Psychol. Sport. Exerc. 2020, 47, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, C.J.; Stock, M.L.; Molloy, B.K.; Beekman, J.B.; Klein, W.M.P.; Butler, N. Combining a UV photo intervention with self-affirmation or self-compassion exercises: Implications for skin protection. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 43, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutcher, J.M.; Eisenberger, N.I.; Woo, H.; Klein, W.M.P.; Harris, P.R.; Levine, J.M.; Creswell, J.D. Neural mechanisms of self-affirmation’s stress buffering effects. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2020, 15, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Kim, Y.; Park, S. Effect of Psychological Distance on Intention in Self-Affirmation Theory. Psychol. Rep. 2020, 123, 2101–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppin, M.; Malamuth, N.M. Priming Self-Affirmation Reduces the Negative Impact of High Rape Myth Acceptance: Assessing Women’s Perceptions and Judgments of Sexual Assault. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP3728–NP3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, E.; Herrmann, S.D.; Kisbu-Sakarya, Y. Adapting the values affirmation intervention to a multi-stereotype threat framework for female students in STEM. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 23, 1587–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, K.T.; Chen, Z.; Wong, W.Y. Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories Following Ostracism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 46, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turetsky, K.M.; Purdie-Greenaway, V.; Cook, J.E.; Curley, J.P.; Cohen, G.L. A psychological intervention strengthens students’ peer social networks and promotes persistence in STEM. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba9221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapa, L.J.; Diemer, M.A.; Roseth, C.J. Can a values-affirmation intervention bolster academic achievement and raise critical consciousness? Results from a small-scale field experiment. Soc. Psychol. Educ. An. Int. J. 2020, 23, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, L. Application of Values Affirmation Intervention in Undergraduate Pre-Calculus Courses; The University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2020; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10150/641359 (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Rosenberg, M.S. The file-drawer problem revisited: A general weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution 2005, 59, 464–468. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, T.D.; Doucouliagos, H. Meta-regression approximations to reduce publication selection bias. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F. Detecting and Correcting the Lies That Data Tell. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, A.; Klein, W.M.P. Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self Identity 2006, 5, 289–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Spreckelsen, T.F.; Cohen, G.L. A meta-analysis of the effect of values affirmation on academic achievement. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 77, 702–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Kite, M.E. Are stereotypes of nationalities applied to both women and men? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Eibach, R.P. Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex. Roles A J. Res. 2008, 59, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, N.; Scircle, M.M.; Hunsinger, M. Female peers in small work groups enhance women’s motivation, verbal participation, and career aspirations in engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4988–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzlicht, M.; Ben-Zeev, T. A threatening intellectual environment: Why females are susceptible to experiencing problem-solving deficits in the presence of males. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 11, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.C.; Steele, C.M.; Gross, J.J. Signaling threat: How situational cues affect women in math, science, and engineering settings. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnie, R.J.; Stroud, C.; Breiner, H. Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, G.L.; Garcia, J. Educational Theory, Practice, and Policy and the Wisdom of Social Psychology. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2014, 1, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, A.; LaGrant, B.; Spiteri, A.; Kushnir, T.; Anderson, A.K.; De Rosa, E. Face-to-face learning enhances the social transmission of information. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannucci, C.J.; Wilkins, E.G. Identifying and avoiding bias in research. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, S.; Mufarrih, S.H.; Qureshi, N.Q.; Khan, F.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.N. Academic Performance in Adolescent Students: The Role of Parenting Styles and Socio-Demographic Factors—A Cross Sectional Study From Peshawar, Pakistan. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrai, K.; Motlagh, S.E.; Zalani, H.A.; Parhon, H. The relationship between academic motivation and academic achievement students. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burson, A.; Crocker, J.; Mischkowski, D. Two types of value-affirmation: Implications for self-control following social exclusion. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2012, 3, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, H.; Cooper, J.; Slkurnik, I.; Aronson, J. When Bad Things Happen to Good Feedback: Exacerbating the Need for Self-Justification with Self-Affirmations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkin, H.; Etchezahar, E.; Ungaretti, J. Personalidad y autoestima desde el modelo y la teoría de los cinco factores. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264348268_Personalidad_y_Autoestima_desde_el_modelo_y_la_teoria_de_los_Cinco_Factores (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Aronson, J.; Lustina, M.J.; Good, C.; Keough, K.; Steele, C.M.; Brown, J. When White men can’t do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 35, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.R.; Neuberg, S.L. From stereotype threat to stereotype threats: Implications of a multi-threat framework for causes, moderators, mediators, consequences, and interventions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Moderators | Classification or Category |

|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | |

| Cultural origin | African American |

| Latin American | |

| Ethnic minority | |

| Others | |

| Age range | 11 to 14 years old |

| 15 to 17 years old | |

| 18 to 23 or older | |

| Economic status | Medium |

| Low | |

| Sample size | Large sample (n > 500 students) |

| Small sample (n < 500 students) | |

| Dominant group in the sample | African American, Latin American, or ethnic minority |

| American or European (Caucasian) | |

| Design characteristics | |

| Execution modality | Face-to-face |

| Virtual | |

| Rigor of randomization | Use of software |

| Does not use software | |

| Dependent variable type | Psychological |

| Physical | |

| Academic performance | |

| Self-affirmation intervention style | Classical intervention (based on important values) |

| No classical intervention | |

| Placebo style | Classical activity (based on unimportant values) |

| No classical activity | |

| Time of the intervention | Before stressful academic event |

| During stressful academic event | |

| After stressful academic event | |

| Study presentation | Routine academic activity |

| Activity for research | |

| Teacher role | Active |

| Passive |

| Study(s) [Ref] | Year and Country | Sample Characteristics | Methodological Characteristics | Effect Size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Origin | Age Range | NC/NE | Variables | Results | Cohen’s d | Variance | ||

| Cohen et al. Study 1 [17] | 2006, US | African Americans and European Americans | 12–13 | 243 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.26 * | 0.0166 |

| Cohen et al. Study 2 [17] | 2006, US | African Americans and European Americans | 12–13 | 243 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.26 * | 0.0106 |

| Cohen et al. [8] | 2009, US | African Americans and European Americans | 12–14 | 385 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.31 * | 0.0105 |

| Bowen et al. [7] | 2013, US | African Americans and ethnic minorities | 11–14 | 74/58 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.52 * | 0.0318 |

| Thomaes et al. Study 1 [40] | 2012, NL | Dutch | 11–14 | 85/88 | Prosocial feelings | (+) | 0.47 * | 0.0143 |

| Thomaes et al. Study 2 [40] | 2012, NL | Dutch | 11–14 | 81/82 | Prosocial behaviors | (+) | 0.19 * | 0.0156 |

| Thomaes et al. [41] | 2009, NL | Caucasians | 12–15 | 405 | Narcissistic aggression | (=) | 0.10 | 0.0127 |

| Armitage [42] | 2012, GB | Caucasians | 13–16 | 105/115 | Perceived threat Self-esteem Current body shape Desired body shape Body satisfaction Body self-esteem | (−/+) | 0.43 * | 0.0182 |

| Sherman et al. Study 1 [10] | 2013, US | Caucasians and Latin Americans | 11–14 | 92/92 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.33 * | 0.0222 |

| Sherman et al. Study 2 [10] | 2013, US | Caucasians and Latin Americans | 11–14 | 79/72 | Academic performance Interpretation level Daily adversity | (+) | 0.52 * | 0.0207 |

| Bratter et al. [6] | 2016, US | African Americans, Caucasians, and Hispanics | 14–15 | 456/430 | Academic performance | (=) | 0.09 | 0.0137 |

| Cook et al. Study 1 [9] | 2012, US | African Americans and Caucasians | 12–14 | 361 | Academic affiliation | (=) | 0.16 | 0.0110 |

| Cook et al. Study 2 [9] | 2012, US | African Americans and Caucasians | 12–14 | 121 | Academic affiliation and academic performance | (+) | 0.45 * | 0.0343 |

| Lokhande and Müller [43] | 2019, DE | Ethnic minorities | 12–13 | 294/374 | Academic performance | (=) | 0.14 | 0.0366 |

| Binning et al. [44] | 2019, US | Caucasians and ethnic groups | 11–14 | 145 | School trust Discipline incidents | (−/+) | 0.40 * | 0.0281 |

| Hoffman and Kurtz-Costes [45] | 2019, US | American Indians | 11–14 | 212 | Motivation for science | (=) | 0.14 | 0.0189 |

| Liu and Huang [46] | 2019, CN | Asians | 15–16 | 48/47 | Self-integration Coping with homework Academic performance Perceived value | (−/+) | 0.42 * | 0.0423 |

| Harackiewicz et al. [24] | 2014, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | M = 19.27, SD = 1.15 | 396/402 | Performance gap Academic performance | (−/+) | 0.22 * | 0.0263 |

| Miyake et al. [25] | 2010, US | 18–22 | 399 | Gender gap Learning | (=) | 0.15 * | 0.0216 | |

| Taylor and Walton [23] | 2011, US | African Americans | 18–22 | 29 | Learning | (+) | 0.83 * | 0.0138 |

| Baker et al. [47] | 2020, US | Caucasians and ethnic groups | 551/564 | Academic performance | (=) | 0.09 | 0.0036 | |

| Bayly and Bumpus [48] | 2019, US | Ethnic minorities | 18–19 | 107/389 | Academic performance | (=) | 0.00 | 0.0135 |

| Blanton et al. [49] | 2013, US | M = 18.7, SD = 1.16 | 116 | Discomfort with the threat Willingness to have unprotected sex | (−/+) | 0.43 * | 0.0355 | |

| Brady et al. [31] | 2016, US | Latinos | 18–20 | 183 | Academic performance Adaptive appropriateness Academic belongingness Spontaneous affirmation Fear of school Optimism Rumination Problem analysis | (+) | 0.75 * | 0.0204 |

| Cameron et al. [50] | 2015, GB | Caucasians and ethnic groups | 16–24 | 799/696 | Consumption of fruits and vegetables Physical activity Alcohol consumption Tobacco consumption Smoking in college | (−/+) | 0.12 * | 0.0286 |

| Churchill et al. [51] | 2018, GB | 18–33 | 32/35 | Musical performance | (=) | 0.00 | 0.0598 | |

| De Clercq et al. [52] | 2019, BE | 18–19 | 129/123 | Self-affirmation | (+) | 0.47 * | 0.0163 | |

| Covarrubias et al. Study 1 [53] | 2016, US | Latinos | 11–14 | 81 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.19 * | 0.0106 |

| Covarrubias et al. Study 2 [53] | 2016, US | Latinos and Americans of European origin | 11–14 | 269 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.22 * | 0.0113 |

| Ehret and Sherman [54] | 2018, US | Caucasians and ethnic groups | 74/66 | Abstinence from alcohol | (=) | 0.00 | 0.0356 | |

| Epton et al. [55] | 2014, GB | Caucasians and ethnic groups | 18–19 | 709/736 | Tobacco use Drug use Hospital admissions Descriptive norms Perception of control | (−/+) | 0.12 * | 0.0199 |

| Goyer et al. [56] | 2017, US | Latinos and Caucasians | 11–14 | 185 | Academic preparation Attendance to selective schools | (+) | 0.48 * | 0.0227 |

| Gregory et al. [57] | 2017, US | Caucasian | 18–22 | 64 | Self-pity Perception of pain Resistance to pain | (+) | 0.60 * | 0.0139 |

| Harackiewicz et al. [58] | 2016, US | African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans | 18–19 | 1040 | Academic performance Performance gap | (+) | 0.28 * | 0.0254 |

| Hernandez et al. [59] | 2017, US | Latinos | 11–14 | 67 | Threat to identity | (=) | 0.00 | 0.0615 |

| Jones and Huey [60] | 2020, US | Caucasians, Latinos, and African Americans | 18–24 | 38/44 | Academic performance Perception of self-integration Social adjustment | (=) | 0.13 | 0.0130 |

| Jordt et al. [61] | 2017, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | 18–22 | 970/963 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.27 | 0.0156 |

| Kamboj et al. [62] | 2016, GB | 18–35 | 278/250 | Pro-social feelings Alcohol consumption Intention to reduce consumption Message derogation Perceived threat Commitment to the threatening message | (−/+) | 0.23 * | 0.0109 | |

| Kim and Niederdeppe [63] | 2016, SG | Caucasians and Asians | 18–34 | 74/76 | Negative cognitive responses Perceived risk of alcohol consumption | (=) | 0.28 | 0.0267 |

| Lannin et al. [64] | 2013, US | European Americans and ethnic groups | 19–46 | 84 | Self-stigma Willingness to seek help | (−/+) | 0.24 * | 0.0627 |

| Lannin et al. [65] | 2020, US | European Americans and ethnic groups | 18–22 | 152 | Positive mood Negative mood Psychological distress | (−/+) | 0.45 * | 0.0295 |

| Layous et al. [66] | 2017, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | M = 19.12, SD = 1.28 | 57/48 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.39 * | 0.0391 |

| Meier et al. [67] | 2015, US | Caucasians | 18–35 | 52/58 | Importance of the problem AR Risk perception AR Alcohol use Protective Strategies AR | (=) | 0.16 | 0.0368 |

| Norman and Wrona-Clarke [68] | 2016, GB | Caucasians | M = 22.58, SD = 6.31 | 105/104 | Reactivity of AR messages Message evaluation AR Perceived Risk AR Intention to binge drink Binge drinking | (=) | 0.12 | 0.0192 |

| Norman et al. [69] | 2018, GB | Caucasians | M = 18.76, SD = 1.94 | 738 | Frequency of excessive consumption AR | (+) | 0.13 * | 0.0054 |

| Peters et al. [70] | 2017, US | Caucasians and African Americans | 17–59 | 194 | Subjective numerical capacity | (=) | 0.29 | 0.0208 |

| Rosas et al. [71] | 2017, US | Caucasians, Latinos, and ethnic minorities | 18–35 | 143 | Self-esteem Intention to consume sugar-sweetened beverages | (+) | 0.24 * | 0.0135 |

| Sereno et al. [72] | 2020, US | Caucasians, Latinos, and ethnic minorities | M = 20.04, SD = 2.69 | 157 | Self-assessment Oral participation | (+) | 0.45 * | 0.0267 |

| Shapiro et al. Study 3 [73] | 2013, US | African Americans | 18–24 | 37 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.19 * | 0.0271 |

| Shapiro et al. Study 4 [73] | 2013, US | African Americans | 18–24 | 75 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.57 * | 0.0555 |

| Tibbetts et al. Study 1 [74] | 2016, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | 18–24 | 69/72 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.23 * | 0.0289 |

| Tibbetts et al. Study 2 [74] | 2016, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | 18–24 | 389/399 | Performance gap Choice of independent topics Choice of interdependent topics | (+) | 0.29 | 0.0066 |

| Walton et al. [75] | 2015, CA | Caucasians, Asians, and ethnic minorities | 18–24 | 228 | Academic performance Importance of negative events Confidence in stress management Self-esteem Gender identification | (−/+) | 0.60 * | 0.0249 |

| Adams et al. Study 1 [76] | 2006, US | Caucasians, European Americans, and Latinos | 18–24 | 44/51 | Perception of racism Belief that whites understate the extent of racism Ratings of the average white person | (+) | 0.58 * | 0.0442 |

| Adams et al. Study 2 [76] | 2006, US | Caucasians, European Americans, and Latinos | 18–24 | 27/36 | Belief that whites understate the extent of racism | (−) | 0.67 * | 0.0688 |

| Borman et al. [15] | 2016, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | 12–13 | 499/513 | Cumulative seventh grade GPA Fall reading test Fall math test Spring reading test Spring math test Spring language usage test | (−/+) | 0.05 | 0.0040 |

| Briñol et al. Study 1 [77] | 2007, ES | 18–24 | 111 | Manipulation check (index of personal importance) | (+) | 2.51 * | 0.0644 | |

| Briñol et al. Study 2 [77] | 2007, ES | 18–24 | 73 | Manipulation check (index of personal importance) | (+) | 1.84 * | 0.0781 | |

| Briñol et al. Study 3 [77] | 2007, ES | 18–24 | 87 | Attitudes | (−) | 0.52 * | 0.0475 | |

| Briñol et al. Study 4 [77] | 2007, ES | 18–24 | 91 | Confidence | (+) | 0.63 * | 0.0461 | |

| Correll et al. [78] | 2004, CA | Canadians | 18–24 | 21/18 | Advocate’s arguments Pro-attitudinal advocate position Argument strength | (−/+) | 1.05 * | 0.1182 |

| Creswell et al. [79] | 2013, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | 18–34 | 73 | Rating value Writing activity RAT score Positive affect | (+) | 1.40 * | 0.0582 |

| Critcher et al. Study 1 [11] | 2010, US | 18–24 | 184 | Defensiveness | (−/+) | 0.15 | 0.0218 | |

| Critcher et al. Study 2a [11] | 2010, US | 18–24 | 76 | Defensively negative score | (−) | 0.57 * | 0.0549 | |

| Critcher and Dunning Study 1 [29] | 2015, US | 18–24 | 75 | Positive feelings of self-worth | (+) | 0.45 * | 0.0547 | |

| Critcher and Dunning Study 2 [29] | 2015, US | 18–24 | 94 | Defensiveness Perspective on the threat | (−/+) | 0.44 * | 0.0435 | |

| Crocker et al. Study 1 [80] | 2008, US | Caucasians, Asians, and other or mixed ethnicity | 17–21 | 70/69 | Rating of loving feelings | (+) | 0.84 * | 0.0319 |

| Crocker et al. Study 2 [80] | 2008, US | Caucasians, Asians, and other or mixed ethnicity | 17–22 | 54 | Acceptance of the article | (+) | 0.63 * | 0.1182 |

| Dillard et al. [81] | 2005, US | Caucasians | 18–24 | 65/65 | Motivated to quit smoking | (+) | 0.39 * | 0.0314 |

| Epton and Harris [82] | 2008, GB | 18–46 | 41/46 | Portions of fruit and vegetables Self-efficacy Response efficacy | (+) | 0.46 * | 0.0474 | |

| Harris and Napper [83] | 2005, GB | 18–24 | 42/40 | Importance of self-affirmed passages Self-positivity Positive attitudes | (+) | 5.08 * | 0.4354 | |

| Harris et al. [84] | 2007, GB | Caucasians | 18–40 | 43/44 | Threat Intention Control Self-efficacy Negative thoughts and feelings | (+) | 0.67 * | 0.0486 |

| Klein et al. Study 1 [85] | 2011, US | 18–24 | 120 | Feelings of vulnerability | (+) | 0.36 * | 0.0339 | |

| Klein et al. Study 2 [85] | 2011, US | 18–24 | 99 | Feelings of vulnerability Intentions | (−/+) | 0.43 * | 0.0413 | |

| Klein and Harris [86] | 2009, US | 18–24 | 118 | Attentional bias toward threat | (+) | 0.37 * | 0.0345 | |

| Koole and van Knippenberg [87] | 2007, NL | 18–24 | 88 | Stereotypic word fragments Stereotypic descriptions | (−/+) | 0.93 * | 0.0511 | |

| Koole et al. Study 1 [88] | 1999, NL | 18–24 | 60 | Value of the AVL subscale Recognition accuracy | (−/+) | 1.49 * | 0.0930 | |

| Koole et al. Study 2 [88] | 1999, NL | 18–24 | 71 | Value of the AVL | (+) | 1.84 * | 0.0801 | |

| Koole et al. Study 3 [88] | 1999, NL | 18–24 | 70 | Value of the AVL Recognition accuracy Positive mood Relative evaluation of name letters | (−/+) | 0.99 * | 0.0704 | |

| Legault et al. [89] | 2012, CA | 18–24 | 35 | Errors of commission Waveform amplitude | (−/+) | 0.82 * | 0.1240 | |

| Martens et al. Study 2 [22] | 2006, US | 18–24 | 52 | Items correct on math SATs | (+) | 0.55 * | 0.0799 | |

| Reed and Aspinwall [90] | 1998, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asian Americans, Biracials, Hispanics, and others | 17–54 | 61 | Reduced bias processing of threatening health information Reading time risk disconfirming Number of facts recalled Perceived control over reducing caffeine consumption | (−/+) | 0.60 * | 0.0688 |

| Schimel et al. Study 1 [91] | 2004, CA | 18–24 | 49 | Self-handicapping attributions Performance measures | (−/+) | 0.57 * | 0.085 | |

| Schmeichel and Martens Study 1 [92] | 2005, US | 18–24 | 65 | Percept negative to anti-U.S. essay | (−) | 0.50 * | 0.0634 | |

| Schmeichel and Martens Study 2 [92] | 2005, US | 18–24 | 54 | Death-related thoughts | (−) | 0.54 * | 0.0768 | |

| Schmeichel and Vohs Study 1 [93] | 2009, US | 18–24 | 63 | Positive mood | (+) | 0.44 * | 0.0650 | |

| Schmeichel and Vohs Study 2 [93] | 2009, US | 18–24 | 72 | Puzzle persistence | (+) | 0.94 * | 0.0617 | |

| Schmeichel and Vohs Study 3 [93] | 2009, US | 18–24 | 29 | Behavioral descriptions | (+) | 0.74 * | 0.1474 | |

| Sherman et al. [94] | 2009, US | Caucasians, Asians, Americans, other ethnicities | 18–24 | 49 | Concerns about failure Worrying during exam | (−) | −0.57 * | 0.085 |

| Sherman et al. Study 1 [95] | 2000, US | 18–24 | 60 | Feel better about selves Point to most important value Accepting of threatening information Reduced caffeine consumption | (+) | 1.14 * | 0.0791 | |

| Sherman et al. Study 2 [95] | 2000, US | 18–24 | 61 | Similar risk Considered risk of HIV Perceptions of risk | (+) | 0.57 * | 0.0683 | |

| Shrira and Martin Study 1 [96] | 2005, US | 18–24 | 101 | Use of stereotypes Left hemisphere activation | (+) | 0.50 * | 0.0409 | |

| Shrira and Martin Study 2 [96] | 2005, US | 18–24 | 180 | Left hemisphere activation Stereotyping | (−/+) | 0.33 * | 0.0226 | |

| Sivanathan et al. Study 2 [97] | 2008, US | 18–24 | 38 | Reinvest funds in initially chosen Commitment to job candidate | (−) | 0.94 * | 0.1169 | |

| Sivanathan et al. Study 3 [97] | 2008, US | 18–24 | 55 | Commitment to job candidate | (−/+) | 0.61 * | 0.0748 | |

| Spencer et al. Study 3 [98] | 2001, US | 18–24 | 24 | Choice downward comparisons Choice upward comparisons | (−/+) | 0.89 * | 0.1840 | |

| Stone et al. Study 1 [99] | 2011, US | Caucasians, Hispanics, Asians, and African Americans | 18–24 | 179 | Desire to meet target race | (+) | −0.30 * | 0.0226 |

| Stone et al. Study 2 [99] | 2011, US | Caucasians, Hispanics, Asians, and African Americans | 18–24 | 102 | Desire to meet target race Empathy Guilt Perceived injustice Stereotyped views | (+) | −0.59 * | 0.0413 |

| van Koningsbruggen et al. [100] | 2009, NL | 18–24 | 84 | Reaction time as a function of threat-related perceptions of message quality Reduction in caffeine consumption | (+) | 0.47 * | 0.0489 | |

| Vohs et al. Study 1 [101] | 2013, US | 18–31 | 52 | Disengagement from a life goal | (+) | 0.47 * | 0.0571 | |

| Vohs et al. Study 2 [101] | 2013, US | 18–24 | 132 | Performance expectations Dampening effect Interest in performing an additional task | (+) | 0.36 * | 0.0308 | |

| Vohs et al. Study 3 [101] | 2013, US | 18–24 | 119 | More effort to task Dampening effect Effort to additional task Effort to attempt RAT problems | (−/+) | 0.42 * | 0.0344 | |

| Vohs et al. Study 4 [101] | 2013, US | 18–24 | 56 | Negative self-perceptions of intelligence Self-perceptions of intelligence Self-efficacy perceptions Performance in the second set of RAT items | (−/+) | 0.59 * | 0.0746 | |

| Wakslak and Trope Study 1 [102] | 2009, US | 18–24 | 24 | Self-concept clarity | (+) | 0.92 * | 0.1844 | |

| Wakslak and Trope Study 2 [102] | 2009, US | 18–24 | 45 | Preferences for high-level action identifications | (+) | 0.73 * | 0.0948 | |

| Zárate and Garza Study 1 [103] | 2002, US | Mexicans, Anglos, African Americans, and Asian Americans | 18–24 | 120 | Prejudices | (−) | 0.36 * | 0.0339 |

| Zhao et al. [104] | 2014, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and other races | 18–24 | 116 | Quitting intentions | (+) | 0.29 * | 0.0348 |

| Sillero-Rejon et al. [105] | 2018, GB | 18–24 | 64/64 | Avoidance Reactance Susceptibility Effectiveness Motivation to drink less Self-efficacy to drink less | (=) | 0.18 | 0.0313 | |

| Pauketat et al. Study 1 [106] | 2016, US | 18–24 | 61 | Affective forecasts Appraisal of negative event as less disturbing | (+) | 1.02 * | 0.0741 | |

| Pauketat et al. Study 2 [106] | 2016, US | 18–24 | 47 | Affective forecasts Appraisal of negative event as less disturbing | (+) | .71 * | 0.0905 | |

| Gu et al. [107] | 2019, CN | 18–24 | 48 | Feedback-related negativity | (+) | 0.82 * | 0.0903 | |

| Taillandier-Schmitt et al. [108] | 2012, FR | 18–43 | 40/55 | Performance scores Temporal performance scores | (+) | 0.42 * | 0.0441 | |

| Hanselman et al. [32] | 2017, US | African Americans and Hispanics | 12–14 | 166/165 | Academic performance | (+) | 0.24 * | 0.0122 |

| Borman et al. [109] | 2018, US | Caucasians and African Americans | 12–14 | 920 | GPA | (+) | 0.25 * | 0.0044 |

| Borman et al. [110] | 2021, US | Caucasians and racial/ethnic groups | 11–17 | 473/479 | GPA | (+) | 0.01 | 0.0042 |

| Serra-Garcia et al. [111] | 2020, US | 18–24 | 283 | Exam scores | (−) | −0.24 * | 0.0142 | |

| Hayes et al. Study 1 [112] | 2019, US | Latinos, African Americans, and Asian Americans | 10–13 | 116 | Overall semester grade | (=) | 0.00 | 0.0345 |

| Hayes et al. Study 2 [112] | 2019, US | Caucasians, Latinos, and Africans Americans | 18–22 | 273 | GPA | (=) | 0.00 | 0.0147 |

| Hadden et al. [113] | 2020, GB | 11–14 | 562 | Academic performance Levels of stress | (−/+) | 0.21 * | 0.0071 | |

| Scott et al. [114] | 2013, AU | 18–24 | 67/54 | Intentions to reduce alcohol consumption | (+) | 0.37 * | 0.0340 | |

| Perry et al. [115] | 2021, US | Caucasians and African Americans | 20–43 | 416 | Perceived residency competitiveness | (+) | 0.20 * | 0.0097 |

| Dee [116] | 2015, US | Caucasians, African Americans, and Hispanics | 12–14 | 885 | Grade in treated subject | (−/+) | 0.30 * | 0.0046 |

| Protzko and Aronson [117] | 2016, US | Caucasians, Hispanics and Africans Americans | 13–15 | 243 | Overall GPA | (=) | 0.06 | 0.0165 |

| Knight and Norman [118] | 2016, GB | Caucasians | 18–24 | 307 | Self-affirmation manipulation | (+) | 0.38 * | 0.0133 |

| Kim et al. [119] | 2022, US | Hispanics and African Americans | 9–10 | 29/37 | Affect/emotion in relation to academic environments or tasks | (=) | 0.27 | 0.0617 |

| More et al. [120] | 2022, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | 18–28 | 125/129 | Fear and defensive processing Exercise intentions | (=) | 0.14 | 0.0158 |

| Smith et al. [121] | 2021, US | Caucasians and ethnic minorities | 18–24 | 361 | Task engagement | (+) | 0.52 * | 0.0115 |

| Kim et al. Study 1 [122] | 2022, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and others | M = 27.9 | 1277 | GPA | (+) | 0.07 * | 0.0031 |

| Pandey et al. [123] | 2021, IN | Indians | 22–27 | 40/40 | Well-being | (+) | 0.94 * | 0.0709 |

| Celeste et al. [124] | 2021, GB | Afro-descendants and Caucasians | 11–13 | 43/42 | Cognitive performance | (=) | 0.05 | 0.0476 |

| Li et al. [125] | 2022, CA, CN | Asians and Caucasians | M = 18.13, SD = 1.65 | 159/137 | Psychological well-being | (=) | 0.02 | 0.0136 |

| Borman et al. [126] | 2022, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asians, Latins | 12–14 | 2149 | Suspensions | (−) | −0.28 * | 0.0019 |

| Binning et al. [127] | 2021, US | Caucasians, African American, Latins, and Asian American | 11–14 | 145 | GPA | (+) | 0.45 * | 0.0283 |

| Pilot and Stutts [128] | 2023, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and others. | 18–22 | 238 | Body dissatisfaction Negative mood state | (=) | 0.06 | 0.0168 |

| Strachan et al. [129] | 2020, CA | Caucasians and Asians | 18–58 | 120 | Exercise task self-efficacy | (+) | 0.17 * | 0.0339 |

| Hagerman et al. [130] | 2020, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asians, Latinos | M = 19.35, SD = 1.61 | 167 | Negative modo Absent-exempt Perceived skin damage Perceived vulnerability Intentions to protect skin | (=) | 0.10 | 0.0241 |

| Dutcher et al. [131] | 2020, US | M = 19.3; SD = 1.35 | 27 | Stressful Academic performance | (−/+) | 1.24 * | 0.1770 | |

| Shin et al. Study 2 [132] | 2020, KR | M = 21.04, SD = 2.07 | 75 | Acceptance of the threatening information | (−) | 0.89 * | 0.0586 | |

| Huppin and Malamuth [133] | 2022, US | Asian American, European American, Hispanic American, African American, and others | 18–24 | 70 | Affirmative consent Conceptualization of consent Knowledge and awareness Rape beliefs Fairness of the outcome | (−/+) | 0.61 * | 0.0598 |

| Çetinkaya et al. Study 1 [134] | 2020, TR | M = 21.88, SD = 1.34 | 60 | Task performance | (+) | 0.84 * | 0.0725 | |

| Poon et al. Study 4 [135] | 2020, CN | M = 20.78, SD = 1.70 | 178 | Conspiracy beliefs | (=) | 0.83 | 0.0225 | |

| Turetsky et al. [136] | 2020, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and others | 18–44 | 108/118 | Closeness centrality Degree centrality Maintaining existing friendships Forming new friendships | (+) | 0.35 * | 0.0193 |

| Rapa et al. [137] | 2020, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and others | M = 14.97 | 28/25 | GPA | (+) | 0.54 | 0.0785 |

| Bosch [138] | 2020, US | Caucasians, African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and others | 18–24 | 221/246 | Academic performance | (=) | 0.03 | 0.0086 |

| Moderator | R2 | β | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | |||

| Cultural origin | |||

| “Other” (Caucasian, European, or Asian) | 7.07% | β = −0.21, z = −3.87, p < 0.001 | (−) |

| Age Ranges (ARs) | |||

| 11–14 years old (AR1) | 5.66% | β = −0.22, z = −3.45, p < 0.001 | (−) |

| 18–23 years old (AR3) | 7.42% | β = 0.24, z = 3.98, p < 0.001 | (+) |

| Sample Size | |||

| Small sample (n > 500 students) | 7.72% | β = 0.28, z = 4.04, p < 0.001 | (+) |

| Large sample (n < 500 students) | 7.72% | β = −0.28, z = −4.04, p < 0.001 | (−) |

| Dominant Group in the Sample | |||

| American, European, or Asian (Caucasian) | 6.22% | β = −0.20, z = −3.59, p < 0.001 | (−) |

| African American, Latino, or ethnic minority | 7.07% | β = −0.18, z = −2.25, p < 0.05 | (−) |

| Design characteristics | |||

| Execution modality | |||

| Face-to-face | 5.26% | β = 0.26, z = 3.28, p < 0.05 | (+) |

| Virtual | 2.29% | β = −0.13, z = −2.14, p < 0.05 | (−) |

| Rigor of Randomization | |||

| Use of software | 4.33% | β = −0.25, z = −2.97, p < 0.05 | (−) |

| Does not use software | 3.52% | β = 0.19, z = 2.66, p < 0.05 | (+) |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Psychological (DV1) | 12.08% | β = 0.28, z = 5.19, p < 0.001 | (+) |

| Academic performance (DV3) | 6.29% | β = −0.20, z = 3.59, p < 0.001 | (−) |

| Self-affirmation intervention style | |||

| Classical intervention (based on important values) | 7.87% | β = −0.27, z = −4.06, p < 0.001 | (−) |

| Timing of Intervention | |||

| Before stressful academic event | 7.79% | β = −0.22, z = −4.04, p < 0.001 | (−) |

| During stressful academic events | 3.70% | β = −0.23, z = −2.81, p < 0.05 | (−) |

| Teacher role | |||

| Active | 4.63% | β = −0.20, z = −3.10, p < 0.05 | (−) |

| Fail Safe Number | |

|---|---|

| Rosenthal (0.050) | 43.646 |

| Rosenberg Normal | 32.963 |

| Rosenberg t-N1/t-N+ | 22.790/23.178 (three iterations) |

| Sample | PET | PEESE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β0 | β1 | β0 | β1 | |

| Full | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.05) | 2.57 ** | 0.14 ** (0.09, 0.18) | 7.96 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escobar-Soler, C.; Berrios, R.; Peñaloza-Díaz, G.; Melis-Rivera, C.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Ponce-Correa, F.; Flores, J. Effectiveness of Self-Affirmation Interventions in Educational Settings: A Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010003

Escobar-Soler C, Berrios R, Peñaloza-Díaz G, Melis-Rivera C, Caqueo-Urízar A, Ponce-Correa F, Flores J. Effectiveness of Self-Affirmation Interventions in Educational Settings: A Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2024; 12(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscobar-Soler, Carolang, Raúl Berrios, Gabriel Peñaloza-Díaz, Carlos Melis-Rivera, Alejandra Caqueo-Urízar, Felipe Ponce-Correa, and Jerome Flores. 2024. "Effectiveness of Self-Affirmation Interventions in Educational Settings: A Meta-Analysis" Healthcare 12, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010003

APA StyleEscobar-Soler, C., Berrios, R., Peñaloza-Díaz, G., Melis-Rivera, C., Caqueo-Urízar, A., Ponce-Correa, F., & Flores, J. (2024). Effectiveness of Self-Affirmation Interventions in Educational Settings: A Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 12(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010003