Exploring Predictors of Social Media Use for Health and Wellness during COVID-19 among Adults in the US: A Social Cognitive Theory Application

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Theoretical Background

1.2.1. Personal Factors

Demographics

Health Perception

Self-Efficacy

1.2.2. Environmental Factors

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Sampling Methodology

2.2. Measures and Instrumentation

Independent Variables: Personal and Environmental Factors

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. The Characteristics of the Study’s Participants

3. Results

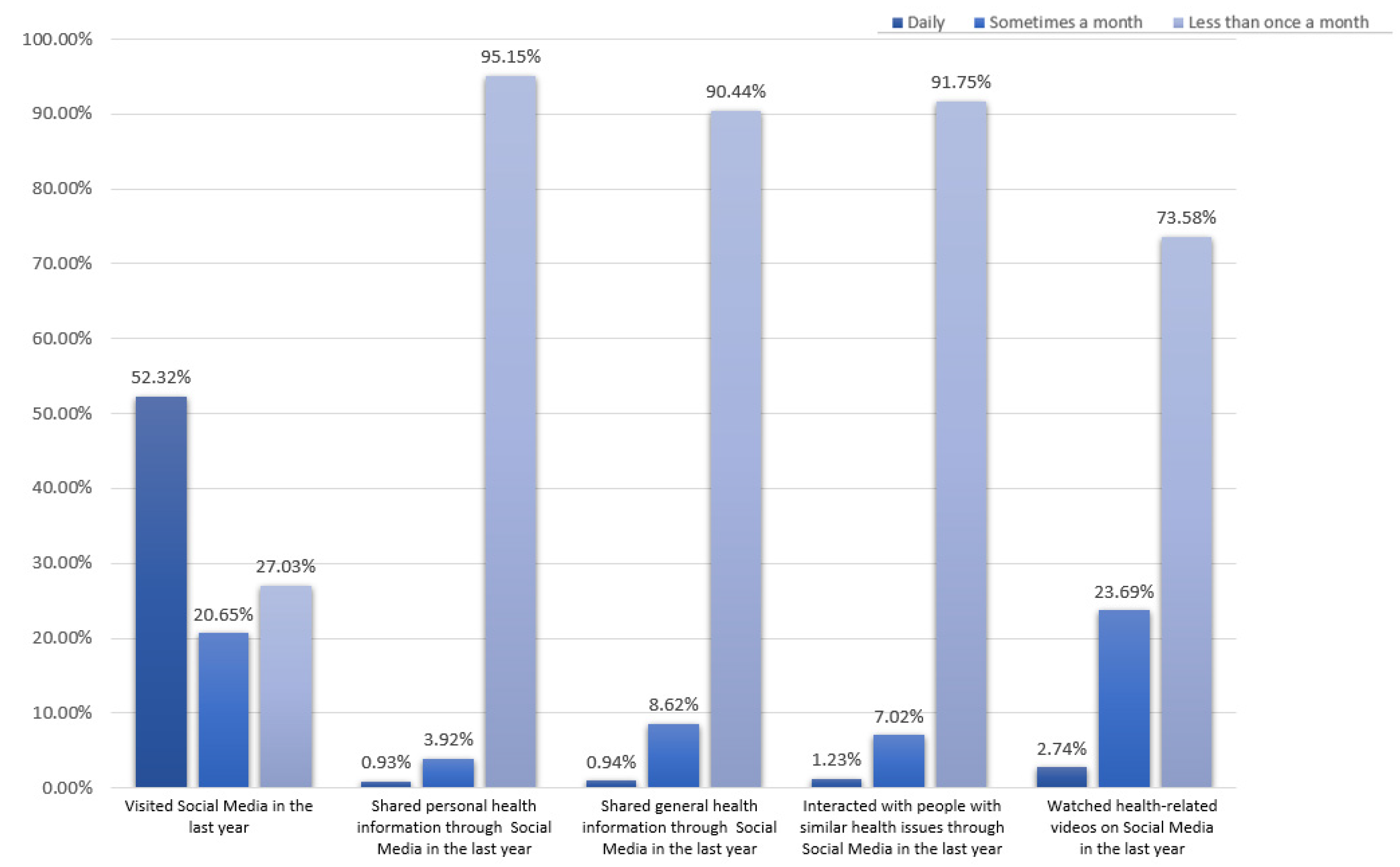

3.1. Use of Social Media across the Different Demographic Groups

3.2. Perception of Social Media Use for Health-Related Purposes

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographics

4.2. Health Perception

4.3. Social Isolation

4.4. Sense of Meaning and Purpose in Life

4.5. Study Contribution

4.6. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Variables of the Study

| Category | Code of the Variable | Variable | Question | Responses |

| Social media use during the last 12 months | Soc_MedVisited | Visiting social media | In the last 12 months, how often did you visit a social media site? | “Daily,” “sometimes a month,” “less than once a month.” |

| SocMed_SharedPers | Using SM to share personal health information | In the last 12 months, how often did you share personal health information on social media? | “Daily,” “sometimes a month,” “less than once a month.” | |

| SocMed_SharedGen | Using SM to share general health information | In the last 12 months, how often did you share general health-related information on social media (for example, a news article)? | “Daily,” “sometimes a month,” “less than once a month.” | |

| SocMed_Interacted | Using SM to interact with people with similar health issues | In the last 12 months, how often did you interact with people with similar health or medical issues on social media or online forums? | “Daily,” “sometimes a month,” “less than once a month.” | |

| SocMed_WatchedVid | Using SM to watch health-related videos | In the last 12 months, how often did you watch a health-related video on a social media site (for example, YouTube)? | “Daily,” “sometimes a month,” “less than once a month.” | |

| Perceptions of social media use for health-related purposes | SocMed_MakeDecisions | Using SM information to make decisions about their health | How much do you agree or disagree—I can use information from social media to make decisions about my health. | “Strongly agree,” “agree,” “somewhat disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” |

| SocMed_DiscussHCP | using SM information in discussions with their healthcare providers | How much do you agree or disagree—I can use information from social media in discussions with my healthcare provider. | “Strongly agree,” “agree,” “somewhat disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” | |

| SocMed_TrueFalse | Finding it hard to tell if SM information is true or false | How much do you agree or disagree—I find it hard to tell whether health information on social media is true or false. | “Strongly agree,” “agree,” “somewhat disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” | |

| SocMed_SameViews | People on SM have the same views about health as them | How much do you agree or disagree? Most people in my social media networks have the same views about health as I do. | “Strongly agree,” “agree,” “somewhat disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” | |

| MisleadingHealthInformation | Health-related information on SM being misleading. | How much health information do you see on social media that you think is false or misleading? | “Strongly agree,” “agree,” “somewhat disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” | |

| Personal factors | Age | Age categories | What is your age? | “18–34”,“35–49”,“50–64”,“65 or more” |

| Race | Race categories | What is your race? | “White”, “Black”, “Hispanic”, “Other” | |

| Education | Education categories | What is the highest degree you obtained? | “Some high school or less,” “High school graduate,” “Some college,” “College graduate or more” | |

| Income | Income categories | What is your yearly income? | “Less than 20K”, “20k to 35k”, “35k to 50k”, “50k to 75k”, “75k or more” | |

| Gender | Gender categories | What is your gender? | “Female”, “Male” | |

| general health | Health Perception | In general, how would you describe your health? | “Bad”, “good”, “fair” | |

| SelfEfficacy | One’s ability to take care of their health | Overall, how confident are you about taking good care of your health? | “Bad”, “good”, “fair” | |

| Environmental factors | FeelIsolated | Feeling isolated | I feel isolated from others | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” |

| FeelLeftOut | Feeling left out | I feel left out | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” | |

| FeeLPeopleBarelyLKnow | Feel that people barely know them | I feel that people barely know me | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” | |

| FeelPeopleNotWithMe | Feel that people are around but not with them | I feel that people are around me but not with me | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” | |

| PROMIS Social Isolation | Feeling isolated from people | The score of the previous four questions | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” | |

| LifeHasMeaning | Feeling that life has a meaning | My life has meaning | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” | |

| LifeHasPurpose | Feeling that life has a purpose | My life has a purpose | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” | |

| ClearSenseDirection | Having a clear sense of direction in life | I have a clear sense of direction in my life | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” | |

| PROMIS Meaning and Purpose in Life | Having a meaning and purpose to life | The score of the previous questions | “Yes,” “No,” “Somehow” |

References

- Moorhead, S.A.; Hazlett, D.E.; Harrison, L.; Carroll, J.K.; Irwin, A.; Hoving, C. A new dimension of health care: Systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidelberger, C. Health Care Professionals’ Use of Online Social Networks; Dakota State University: Madison, SD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, M.A.; Evans, Y.; Morishita, C.; Midamba, N.; Moreno, M. Parental perceptions of the internet and social media as a source of pediatric health information. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center, P.R. Social Media Fact Sheet; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, M. Healthcare social media for consumer informatics. In Consumer Informatics and Digital Health: Solutions for Health and Health Care; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aghbari, A.A.A.; Hassan, O.E.H.; Dar Iang, M.; Jahn, A.; Horstick, O.; Dureab, F. Exploring the Role of Infodemics in People’s Incompliance with Preventive Measures during the COVID-19 in Conflict Settings (Mixed Method Study). Healthcare 2023, 11, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgie, E.M.; Lai, H.; Cao, B.; Stroulia, E.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Goez, H. Social Media and the Transformation of the Physician-Patient Relationship. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafle, N.K.; Poudel, R.R.; Shrestha, S.M. Noncompliance to diet and medication among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in selected hospitals of Kathmandu, Nepal. J. Soc. Health Diabetes 2018, 6, 090–095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.A.; Ryan, T.; Gray, D.L.; McInerney, D.M.; Waters, L. Social media use and social connectedness in adolescents: The positives and the potential pitfalls. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 31, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J. Digital divides and social network sites: Which students participate in social media? J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2011, 45, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, T. Digital skills and social media use: How Internet skills are related to different types of Facebook use among ‘digital natives’. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontos, E.; Blake, K.D.; Chou, W.-Y.S.; Prestin, A. Predictors of eHealth usage: Insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-Y.S.; Prestin, A.; Lyons, C.; Wen, K.-Y. Web 2.0 for health promotion: Reviewing the current evidence. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e9–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chretien, K.C.; Kind, T. Social media and clinical care: Ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation 2013, 127, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, L.; Evans, Y.; Pumper, M.; Moreno, M.A. Social media use by physicians: A qualitative study of the new frontier of medicine. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, Y.; Zilanawala, A.; Booker, C.; Sacker, A. Social media use and adolescent mental health: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. EClinicalMedicine 2018, 6, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shensa, A.; Escobar-Viera, C.G.; Sidani, J.E.; Bowman, N.D.; Marshal, M.P.; Primack, B.A. Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among US young adults: A nationally-representative study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 182, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bert, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Camussi, E.; Siliquini, R. Risks and threats of social media websites: Twitter and the proana movement. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.-Y.S.; Gaysynsky, A.; Trivedi, N.; Vanderpool, R.C. Using social media for health: National data from HINTS 2019. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report, 100; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, V.; Petkovic, J.; Pardo, J.P.; Rader, T.; Tugwell, P. Interactive social media interventions to promote health equity: An overview of reviews. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy Pract. 2016, 36, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Plotnikoff, R.; Collins, C.; Callister, R.; Morgan, P. Social cognitive theory and physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, B.; Cederberg, K.L.J.; Huynh, T.L.; Silic, P.; Jones, C.D.; Feasel, C.D.; Sikes, E.M.; Baird, J.F.; Silveira, S.L.; Sasaki, J.E.; et al. Social Cognitive Theory variables as correlates of physical activity in fatigued persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 57, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Mou, J. Social media fatigue-Technological antecedents and the moderating roles of personality traits: The case of WeChat. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleofas, J.V.; Rocha, I.C.N. Demographic, gadget and internet profiles as determinants of disease and consequence related COVID-19 anxiety among Filipino college students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6771–6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibb, B. Social media use and perceptions of physical health. Heliyon 2019, 5, e00989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buda, G.; Lukoševičiūtė, J.; Šalčiūnaitė, L.; Šmigelskas, K. Possible effects of social media use on adolescent health behaviors and perceptions. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 1031–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkefi, S.; Asan, O. Perceived Patient Workload and Its Impact on Outcomes During New Cancer Patient Visits: Analysis of a Convenience Sample. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e49490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkefi, S.; Asan, O. The Impact of Patient-Centered Care on Cancer Patients’ QOC, Self-Efficacy, and Trust Towards Doctors: Analysis of a National Survey. J. Patient Exp. 2023, 10, 23743735231151533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social-learning theory of identificatory processes. Handb. Social. Theory Res. 1969, 213, 262. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. Factors affecting adolescents’ screen viewing duration: A social cognitive approach based on the family life, activity, sun, health and eating (FLASHE) survey. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Luo, S.; Mu, W.; Li, Y.; Ye, L.; Zheng, X.; Xu, B.; Ding, Y.; Ling, P.; Zhou, M. Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021.

- National Institute of Health. HINTS 6 Methodology Report; National Institute of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in United States COVID-19 Hospitalizations, Deaths, Emergency Department (ED) Visits, and Test Positivity by Geographic Area; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023.

- National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2022.

- Assari, S.; Khoshpouri, P.; Chalian, H. Combined effects of race and socioeconomic status on cancer beliefs, cognitions, and emotions. Healthcare 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkefi, S. Access and Usage of mobile health (mHealth) for communication, health monitoring, and decision-making among patients with multiple chronic diseases (comorbidities). IISE Trans. Healthc. Syst. Eng. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthmeasures. PROMIS. 2023. Available online: https://www.healthmeasures.net/ (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Cella, D.; Riley, W.; Stone, A.; Rothrock, N.; Reeve, B.; Yount, S.; Amtmann, D.; Bode, R.; Buysse, D.; Choi, S. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, E.A.; DeWalt, D.A.; Bode, R.K.; Garcia, S.F.; DeVellis, R.F.; Correia, H.; Cella, D. New English and Spanish social health measures will facilitate evaluating health determinants. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsman, J.M.; Schalet, B.D.; Park, C.L.; George, L.; Steger, M.F.; Hahn, E.A.; Snyder, M.A.; Cella, D. Assessing meaning & purpose in life: Development and validation of an item bank and short forms for the NIH PROMIS®. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Yadav, S.; Jo, A. The association between electronic wearable devices and self-efficacy for managing health: A cross sectional study using 2019 HINTS data. Health Technol. 2021, 11, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Tutz, G. Multiple imputation using nearest neighbor methods. Inf. Sci. 2021, 570, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Y.S.; Abdelkader, H.; Pławiak, P.; Hammad, M. A novel model to optimize multiple imputation algorithm for missing data using evolution methods. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 76, 103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Social media use for health purposes: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e17917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsi, D. Social media and health care, part I: Literature review of social media use by health care providers. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruska, J.; Maresova, P. Use of social media platforms among adults in the United States—Behavior on social media. Societies 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, F.; Heidari, S. The relationship between critical thinking skills and learning styles and academic achievement of nursing students. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 27, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, I.V.; Kleisiaris, C.F.; Fradelos, E.C.; Kakou, K.; Kourkouta, L. Critical thinking: The development of an essential skill for nursing students. Acta Inform. Medica 2014, 22, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPeck, J.E. Critical Thinking and Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, J.M.; Oxman, A.D.; Mahtani, K.R.; Chalmers, I.; Oliver, S.; Collins, K.; Austvoll-Dahlgren, A.; Hoffmann, T. Critical thinking in healthcare and education. BMJ 2017, 357, j2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R.A.; Klein, W.M. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J. Introduction to Health Behavior Theory; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, W.; Amuta, A.O.; Jeon, K.C. Health information seeking in the digital age: An analysis of health information seeking behavior among US adults. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 1302785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshi, D.; Cotten, S.R.; Bender, A.R. Problematic social media use and perceived social isolation in older adults: A cross-sectional study. Gerontology 2020, 66, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Karim, S.A.; Shensa, A.; Bowman, N.; Knight, J.; Sidani, J.E. Positive and negative experiences on social media and perceived social isolation. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.; Fausset, C.; Farmer, S.; Nguyen, J.; Harley, L.; Fain, W.B. Examining social media use among older adults. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, Paris, France, 1–3 May 2013; pp. 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.S.; Strecher, V.J.; Ryff, C.D. Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16331–16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Shiba, K.; Boehm, J.K.; Kubzansky, L.D. Sense of purpose in life and five health behaviors in older adults. Prev. Med. 2020, 139, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–34 | 939 | 15.02% |

| 35–49 | 1249 | 19.98% | |

| 50–64 | 1834 | 29.33% | |

| 65 or more | 2230 | 35.67% | |

| Gender | Male | 2411 | 38.56% |

| Female | 3841 | 61.44% | |

| Race | White | 3350 | 53.58% |

| Black | 1048 | 16.76% | |

| Hispanic | 1382 | 22.10% | |

| Other | 472 | 7.55% | |

| Education | Less than high school | 387 | 6.19% |

| High school graduate | 1099 | 17.58% | |

| Some college | 1884 | 30.13% | |

| College graduate or more | 2882 | 46.10% | |

| Income | Less than 20k | 969 | 15.50% |

| 20k to 35k | 837 | 13.39% | |

| 35k to 50k | 998 | 15.96% | |

| 50k to 75k | 1243 | 19.88% | |

| 75k or more | 2205 | 35.27% | |

| WorkFullTime | No | 3218 | 51.47% |

| Yes | 3034 | 48.53% | |

| GeneralHealth | Bad | 156 | 2.50% |

| Fair | 936 | 14.97% | |

| Good | 5160 | 82.53% | |

| Self-efficacy | Bad | 337 | 5.39% |

| Somehow | 1421 | 22.73% | |

| Good | 4494 | 71.88% | |

| SocMed MakeDecisions | SocMed DiscussHCP | SocMed TrueFalse | SocMed SameViews | Misleading Health Information | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | |||

| Personal Factors | ||||||||||||

| Demographics | Age | 18–34 | ||||||||||

| 35–49 | 0.406 | 0.9 [0.72–1.14] | 0.015 * | 0.76 [0.62–0.95] | 0.218 | 1.33 [0.94–1.12] | <0.001 *** | 0.8 [0.56–0.67] | <0.001 *** | 0.68 [0.29–0.44] | ||

| 50–64 | 0.002 ** | 0.7 [0.56–0.88] | 0.003 ** | 0.73 [0.59–0.9] | <0.001 *** | 1.54 [1.09–1.3] | <0.001 *** | 0.76 [0.54–0.64] | <0.001 *** | 0.23 [0.11–0.16] | ||

| 65 or more | <0.001 *** | 0.52 [0.4–0.67] | <0.001 *** | 0.63 [0.5–0.79] | <0.001 *** | 2.36 [1.62–1.95] | <0.001 *** | 0.61 [0.42–0.5] | <0.001 *** | 0.11 [0.05–0.08] | ||

| Gender | Male | |||||||||||

| Female | 0.355 | 1.08 [0.92–1.27] | 0.052 | 1.16 [1.01–1.35] | 0.856 | 1.11 [0.88–0.99] | 0.194 | 1.21 [0.96–1.08] | 0.146 | 1.64 [1.25–1.43] | ||

| Race | White | |||||||||||

| Black | <0.001 *** | 1.57 [1.27–1.93] | 0.001 | 1.38 [1.14–1.68] | 0.170 | 0.88 [0.65–0.76] | 0.071 | 1.01 [0.74–0.86] | 0.063 | 1.29 [0.86–1.05] | ||

| Hispanic | 0.004 ** | 1.35 [1.1–1.65] | 0.205 | 1.13 [0.94–1.36] | 0.250 | 0.97 [0.73–0.84] | <0.001 *** | 0.87 [0.65–0.75] | 0.460 | 1.11 [0.79–0.94] | ||

| Other | <0.001 *** | 1.8 [1.39–2.35] | 0.001 | 1.52 [1.2–1.95] | 0.643 | 1.17 [0.77–0.95] | 0.125 | 1.05 [0.69–0.85] | 0.440 | 1.51 [0.84–1.12] | ||

| Education | <High School | |||||||||||

| High school graduate | 0.105 | 0.75 [0.53–1.06] | 0.165 | 0.79 [0.56–1.1] | <0.001 *** | 1.99 [1.22–1.55] | 0.836 | 1.36 [0.78–1.03] | 0.012 * | 1.61 [0.95–1.23] | ||

| Some college | 0.607 | 0.91 [0.66–1.28] | 0.753 | 1.05 [0.76–1.45] | <0.001 *** | 2.32 [1.44–1.82] | 0.95 | 1.3 [0.76–0.99] | <0.001 *** | 3.04 [1.79–2.34] | ||

| College Graduate | 0.668 | 1.07 [0.77–1.51] | 0.267 | 1.2 [0.87–1.67] | <0.001 *** | 2.98 [1.21–4.55] | 0.263 | 1.54 [0.89–1.17] | <0.001 *** | 3.27 [1.89–2.48] | ||

| Income Levels | Less than 20K | |||||||||||

| 20k to 35k | 0.396 | 0.89 [0.67–1.17] | 0.950 | 0.8 [0.61–1.04] | 0.111 | 1.44 [0.96–1.17] | 0.809 | 1.28 [0.83–1.03] | 0.069 | 1.54 [0.98–1.23] | ||

| 35k to 50k | 0.474 | 0.9 [0.69–1.19] | 0.200 | 0.73 [0.57–0.95] | 0.480 | 1.49 [1–1.22] | 0.524 | 1.33 [0.87–1.07] | 0.070 | 1.68 [1.07–1.34] | ||

| 50k to 75k | 0.411 | 0.89 [0.68–1.17] | 0.246 | 0.86 [0.67–1.11] | 0.220 | 1.76 [1.18–1.43] | 0.170 | 1.59 [1.05–1.28] | 0.082 | 2.17 [1.36–1.72] | ||

| 75k or more | 0.290 | 0.74 [0.56–0.97] | 0.36 | 0.77 [0.6–0.98] | 0.670 | 1.67 [1.13–1.36] | 0.190 | 1.57 [1.04–1.28] | 0.095 | 2.5 [1.57–1.97] | ||

| Health-Beliefs & Attitudes | General Health | Bad | ||||||||||

| Fair | 0.886 | 0.96 [0.57–1.63] | 0.064 | 1.13 [0.67–1.9] | 0.406 | 1.25 [0.58–0.85] | 0.550 | 1.33 [0.58–0.88] | 0.413 | 1.29 [0.54–0.84] | ||

| Good | 0.913 | 0.97 [0.57–1.65] | 0.04 * | 1.26 [0.75–2.12] | 0.838 | 1.53 [0.71–1.04] | 0.569 | 1.7 [0.75–1.13] | 0.620 | 1.39 [0.58–0.9] | ||

| Self Efficacy | Bad | |||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.852 | 0.96 [0.66–1.4] | 0.614 | 1.11 [0.76–1.59] | 0.940 | 1.31 [0.75–0.99] | 0.261 | 1.45 [0.8–1.08] | 0.363 | 1.64 [0.83–1.17] | ||

| Good | 0.450 | 1.01 [0.69–1.48] | 0.013 | 1.32 [0.92–1.89] | 0.227 | 1.26 [0.71–0.95] | 0.352 | 1.57 [0.85–1.16] | 0.722 | 1.51 [0.75–1.06] | ||

| Environmental Factors (Psycho-social) | ||||||||||||

| Social Isolation | Feeling Isolated | No | ||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.553 | 1.13 [0.75–1.69] | 0.039 * | 0.97 [0.77–1.22] | 0.026 * | 1.08 [0.74–0.9] | 0.012 * | 1.53 [1.06–1.27] | 0.006 ** | 1.8 [1.1–1.4] | ||

| Yes | 0.010 * | 1.39 [1.08–1.78] | 0.041 * | 0.85 [0.59–1.24] | 0.032 * | 1.16 [0.63–0.85] | 0.036 * | 1.59 [0.84–1.16] | 0.006 ** | 1.68 [0.73–1.12] | ||

| Feeling left out | No | |||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.094 | 0.99 [0.66–1.48] | 0.015 | 1.31 [0.9–1.91] | 0.042 * | 1.31 [0.93–1.11] | 0.039 * | 1.28 [0.91–1.07] | 0.892 | 1.26 [0.82–1.01] | ||

| Yes | 0.017 * | 1.17 [0.93–1.48] | 0.019 * | 1.15 [0.93–1.41] | 0.025 * | 1.44 [0.77–1.05] | 0.074 | 1.45 [0.77–1.05] | 0.528 | 1.34 [0.57–0.87] | ||

| Feeling People Barely Know Me | No | |||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.131 | 1.31 [0.92–1.85] | 0.036 | 1.4 [1.02–1.93] | 0.354 | 1.28 [0.92–1.08] | 0.650 | 1.14 [0.82–0.96] | 0.074 | 2 [0.97–1.39] | ||

| Yes | 0.033 * | 1.27 [1.02–1.6] | 0.014 * | 1.28 [1.05–1.58] | 0.662 | 1.23 [0.72–0.94] | 0.447 | 1.18 [0.69–0.9] | 0.033 * | 1.56 [1.02–1.26] | ||

| Feeling People Not With Me | No | |||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.087 | 1.97 [1.67–3.41] | 0.061 | 0.94 [0.75–1.18] | 0.069 | 1.25 [0.86–1.04] | 0.053 | 1.13 [0.78–0.94] | 0.305 | 1.12 [0.69–0.88] | ||

| Yes | 0.027 * | 1.75 [1.58–2.97] | 0.039 * | 0.86 [0.6–1.22] | 0.078 | 1.28 [0.72–0.96] | 0.028 * | 1.14 [0.63–0.85] | 0.625 | 1.34 [0.62–0.9] | ||

| PROMIS Social Isolation | No | |||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.090 | 1.23 [0.75–1.51] | 0.005 ** | 1.31 [1.08–1.59] | 0.449 | 1.22 [0.92–1.05] | 0.001 ** | 1.46 [1.1–1.26] | 0.003 ** | 1.42 [1.02–1.2] | ||

| Yes | 0.088 | 1.38 [0.74–2.54] | 0.009 ** | 1.08 [1.12–1.92] | 0.407 | 1.95 [0.76–1.22] | 0.010 * | 2.82 [1.11–1.79] | 0.005 ** | 3.36 [0.95–1.79] | ||

| Purpose and Meaning in Life | Life Has Meaning | No | ||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.075 | 0.9 [0.51–1.58] | 0.092 | 1.02 [0.64–1.65] | 0.009 ** | 2.47 [1.14–1.68] | 0.014 * | 2.00 [0.91–1.35] | 0.716 | 1.82 [0.66–1.09] | ||

| Yes | 0.046 * | 0.81 [0.48–1.37] | 0.065 | 0.89 [0.53–1.49] | 0.010 * | 2.14 [0.93–1.4] | 0.009 ** | 2.22 [0.93–1.43] | 0.166 | 2.52 [0.85–1.46] | ||

| Life Has Purpose | No | |||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.013 * | 1.51 [0.91–2.51] | 0.038 * | 1.22 [0.78–1.92] | 0.064 | 1.57 [0.76–1.09] | 0.229 | 1.15 [0.56–0.8] | 0.014 * | 0.89 [0.34–0.54] | ||

| Yes | 0.023 * | 1.43 [0.83–2.46] | 0.019 * | 1.39 [0.85–2.27] | 0.074 | 1.39 [0.63–0.93] | 0.227 | 1.17 [0.52–0.78] | 0.016 * | 1.11 [0.39–0.66] | ||

| Clear Sense of Direction | No | |||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.020 * | 0.72 [0.55–0.95] | 0.046 * | 0.91 [0.72–1.16] | 0.076 | 1.18 [0.8–0.97] | 0.061 | 1.47 [0.99–1.21] | 0.022 * | 1.53 [0.9–1.17] | ||

| Yes | 0.041 * | 1.2 [0.78–1.85] | 0.029 | 1.23 [0.83–1.85] | 0.019 * | 1.77 [0.89–1.26] | 0.033 * | 2.01 [1.03–1.45] | 0.032 * | 2.03 [0.8–1.27] | ||

| PROMIS Meaning and Purpose in Life | No | |||||||||||

| Somehow | 0.046 * | 0.87 [0.53–2.1] | 0.280 | 1.4 [0.75–2.63] | 0.020 * | 2.23 [0.81–1.35] | 0.590 | 1.44 [0.53–0.87] | 0.030 * | 2.43 [0.51–1.61] | ||

| Yes | 0.048 * | 0.89 [0.51–2.16] | 0.360 | 1.36 [0.7–2.62] | 0.006 ** | 1.94 [0.68–1.14] | 0.430 | 1.39 [0.47–0.8] | 0.040 * | 1.92 [0.48–0.86] | ||

| R-squared | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.44 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elkefi, S. Exploring Predictors of Social Media Use for Health and Wellness during COVID-19 among Adults in the US: A Social Cognitive Theory Application. Healthcare 2024, 12, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010039

Elkefi S. Exploring Predictors of Social Media Use for Health and Wellness during COVID-19 among Adults in the US: A Social Cognitive Theory Application. Healthcare. 2024; 12(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleElkefi, Safa. 2024. "Exploring Predictors of Social Media Use for Health and Wellness during COVID-19 among Adults in the US: A Social Cognitive Theory Application" Healthcare 12, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010039