Abstract

Patient activation, broadly defined as the ability of individuals to manage their health and navigate the healthcare system effectively, is crucial for achieving positive health outcomes. The Patient Activation Measure (PAM), a popularly used tool, was developed to assess this vital component of health care. This review is the first to systematically examine the validity of the PAM, as well as study its reliability, factor structure, and validity across various populations. Following the PRISMA and COSMIN guidelines, a search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library, from inception to 1 October 2023, using combinations of keywords related to patient activation and the PAM. The inclusion criteria were original quantitative or mixed methods studies focusing on PAM-13 or its translated versions and containing data on psychometric properties. Out of 3007 abstracts retrieved, 39 studies were included in the final review. The PAM has been extensively studied across diverse populations and geographical regions, including the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Most studies looked at populations with chronic conditions. Only two studies applied the PAM to community-dwelling individuals and found support for its use. Studies predominantly showed a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.80) for the PAM. Most studies supported a unidimensional construct of patient activation, although cultural differences influenced the factor structure in some cases. Construct validity was established through correlations with health behaviors and outcomes. Despite its strengths, there is a need for further research, particularly in exploring content validity and differential item functioning. Expanding the PAM’s application to more diverse demographic groups and community-dwelling individuals could enhance our understanding of patient activation and its impact on health outcomes.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines self-care as “the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a healthcare provider” [1]. At the core of this concept is patient activation, a behavioral notion encompassing an individual’s knowledge, skills, and confidence in managing their health and health care [2]. Patient activation is thought to be integral to self-care and achieving positive population health outcomes, as it empowers patients to play an active role in their health management. Recent research, including a 2022 meta-analysis encompassing nine observational studies, supports the positive impact of high patient activation scores, linking them to decreased visits to emergency departments, fewer hospital admissions, and reduced overall healthcare utilization [3].

However, it is estimated that between 11% and 47% of the population possess low levels of activation, making them less likely to adopt healthy behaviors [4,5]. To enhance patient activation, interventions have been developed and show that a positive change in activation levels correlates with improved self-care behavior. The critical step in this process is measuring patient activation, and this is where tools like the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) come into play [6].

The PAM, crafted by Hibbard and colleagues, outlines four stages of patient activation [6,7]. These stages range from patients acknowledging their pivotal role in their health care to gaining knowledge and confidence for active participation, translating this confidence and knowledge into action, and maintaining an active role in healthcare despite potential challenges [7]. The PAM, a 13-item survey, assesses an individual’s knowledge, skill, and confidence for self-management. It categorizes patients into four levels based on their activation score, which ranges from a lack of understanding of the need for active participation in health (level one) to challenges in maintaining positive health behaviors over time (level four) [6]. The PAM tool has been validated in various patients with chronic diseases but is less frequently validated in the general population [8,9,10].

Given the potential for the widespread application of the PAM in population health systems, it would be important to examine the reliability, validity, strengths, and limitations of the tool. To date, there have not been comprehensive systematic reviews focusing on the PAM tool. Therefore, this review aims to systematically examine the existing literature concerning the validation studies of the PAM tool, including their findings, and the diverse populations and settings in which the PAM has been employed. This would also be carried out in accordance with the latest COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments) guidelines [11] to improve the completeness of the reporting of these studies.

2. Methods

The COSMIN [11] and latest PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [12] were referenced for this systematic review. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42024529845).

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify published studies that have used the PAM questionnaire using combinations of the keywords: [patient activation OR PAM] AND [health care OR patient care]. The search was performed in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library from database inception up till 1 October 2023. The full search strategy for the various databases can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1). The title and abstract of the retrieved searches were screened by two independent researchers (from M.Y.Q.L., Y.Y.T., or Q.X.N.), and the duplicates were removed.

Full texts were retrieved for the articles that met the inclusion criteria: (1) original studies with quantitative or mixed-method methodology, (2) specifically focusing on the PAM-13 or PAM-10 (or translated versions) and reporting the psychometric properties of the tool, and (3) published in English. Commentaries, case reports, case series, and review articles were excluded as well. All disagreements during the screening process were resolved via discussion with the senior author (Q.X.N.). Information was extracted from the selected studies, including author details, year of publication, study design, population characteristics, methodologies used for validation, main findings, and limitations to meet the objectives of this review. The outcomes of the included studies were then descriptively synthesized to arrive at a broader understanding of the validation and psychometric properties of the PAM across different populations.

The included studies were graded according to the COSMIN checklist [13,14] by M.Y.Q.L., A.S.P.T. and Q.X.N. The COSMIN checklist evaluates the methodology quality of each study in nine aspects: (1) content validity, (2) structural validity, (3) internal consistency, (4) cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance, (5) reliability, (6) hypotheses testing for construct validity, and (7) responsiveness. A four-point scale is used to assess each domain (poor, fair, good, or excellent). An overall score for methodological quality in each domain was determined by taking the lowest grade provided for any item within the category.

Given that this is a review of the existing literature and no primary data collection or human participants were directly involved, prior ethical approval was not required.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Retrieval

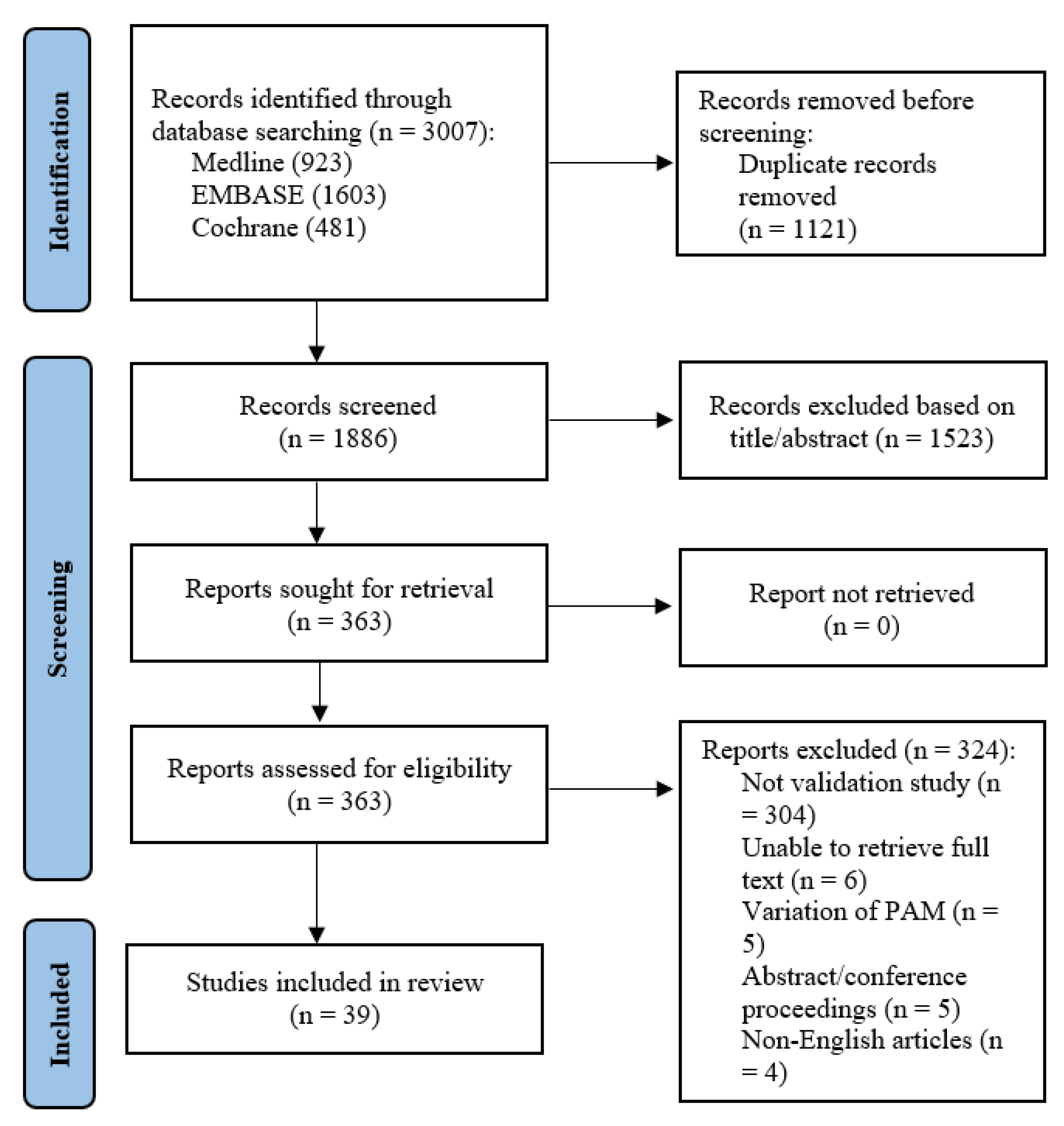

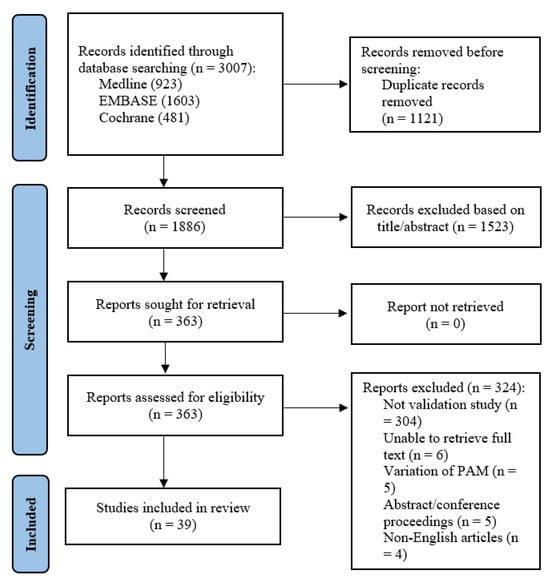

A total of 3007 abstracts were retrieved from the systematic search. After removal of duplicates, 1886 studies remained. After title and abstract screening, 363 articles remained and were sought for full-text review. Six full texts could not be retrieved despite best efforts and manual library search. Of the remaining 357 studies, 304 were not validation or reliability studies pertaining to the PAM, 5 used variations of the PAM e.g., caregiver-PAM, 5 were abstracts or conference proceedings, and 4 did not have English translation. A total of 39 manuscripts [6,8,9,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] were finally included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing the literature search process.

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the studies and their principal findings regarding reliability, validity, and factor analysis, arranged by their geographic regions according to the WHO regional classification [51].

Table 1.

Key characteristics of studies reviewed and their findings regarding reliability, validity, and factor analysis (arranged geographically).

3.2. Populations Sampled

The Patient Activation Measure (PAM) has been extensively studied across diverse populations and geographical regions, including the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. In terms of the distribution, there were 13 studies from the United States [6,15,20,22,26,27,32,33,40,44,46]; 3 studies from Germany [18,19,49] and the Netherlands [25,39,43]; 2 studies from Canada [29,41], Israel [34,35], Malaysia [17,24], Norway [37,38], and Singapore [8,9]; and 1 each from Australia [21], China [48], Denmark [36], Hungary [50], India [28], Iran [47], Italy [23], Korea [16], Portugal [31], and Turkey [30]. These studies primarily focused on adults, including specific groups like those with chronic conditions, cancer, heart disease, and mental health issues. The PAM was effective in measuring activation in populations with chronic conditions, with studies showing its ability to differentiate based on health behaviors and management. Notably, only two studies applied the PAM to the general populace and found support for its use among community-dwelling individuals [8,50].

3.3. Validity and Reliability Studies

The reliability of the PAM, predominantly assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, demonstrates generally high internal consistency across different studies and populations. The values of Cronbach’s alpha ranged mostly above 0.80, indicating strong reliability. A few studies, such as those by Fowles et al. [22] and Zeng et al. [48], report particularly high reliability scores (α > 0.90). This consistency is crucial, as it suggests the PAM tool consistently measures patient activation regardless of the sample population.

Most studies report a single-factor structure for the PAM, suggesting that it measures a unidimensional construct. However, a few studies like those by Lin et al. [33] in the United States and Zakeri et al. [47] in Iran identified multifactor structures, indicating potential cultural or contextual variations in how patient activation is conceptualized or manifested.

The construct validity of the PAM is supported through various methods, including principal component analysis (PCA) and correlations with other measures. The studies often show moderate-to-strong correlations between PAM scores and relevant health behaviors or outcomes. For instance, Eyles et al. [21] found correlations with depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life. Similarly, studies by Bomba et al. [18] and Stepleman et al. [46] found significant correlations between PAM scores and measures of internal and external locus of control and multiple sclerosis self-efficacy, respectively.

While most studies accepted the original content validation by Hibbards et al. [6,26] as sufficient content validation for implementation in their own cohorts, where locally validated, it appears to be robust. For example, Kosar et al. in Turkey highlighted high content validity indices, suggesting that the items of the PAM are well received and considered relevant by the participants [30].

3.4. Cross-Cultural Adaptations and Translations

In other countries in which English may not be the working language, the PAM was translated to a language that was spoken or written by the majority. Across the included studies that translated the PAM and subsequently validated the translated version, all studies followed the prescribed methodology for the cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires, namely forward–backward translation, qualitative assessment by an expert panel, and pilot testing on a small sample representative of the target population [52]. Translated versions of the PAM, such as in Turkey, Portugal, and Iran, indicate that the tool is adaptable in different linguistic and cultural contexts, although this sometimes affects its factor structure.

3.5. Identified Issues

While the PAM is generally reliable across diverse populations, certain subgroups might not be as accurately represented. For instance, Hibbard et al. [26] noted lower reliability for specific subgroups, such as those with no chronic illness, older adults, and those with lower income and education. As highlighted in Table 2, in our appraisal of methodological quality, many studies did not assess content validity in accordance with the COSMIN guidelines. While the reliability and construct validity are well established, the lack of a comprehensive content validity assessment in some studies could question the tool’s comprehensiveness in covering all aspects of patient activation, especially since cultural context does impact on people’s interpretation of questionnaire items. Most studies focused on correlations between PAM scores and other health-related measures to establish construct validity. However, this approach may not fully explore all facets of the patient activation construct, such as psychological, social, and behavioral components. Moreover, some studies indicated the presence of DIF, suggesting that certain items may not have an equivalent meaning across different groups or contexts.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of each study per measurement property.

4. Discussion

Based on the findings of this systematic review, the PAM is a reliable and valid tool for measuring patient activation across various populations. Its adaptability to different languages and contexts, along with its strong correlation with key health outcomes, underscores its utility in both clinical and research settings. The tool’s ability to capture the essence of a patient’s engagement in their health care makes it a valuable asset in patient-centered care models as patient activation is increasingly acknowledged as a key determinant of health outcomes, and it also lends itself to action-oriented insights.

This review systematically synthesizes findings from various studies to evaluate the validity and applicability of the PAM across different populations and settings. High internal consistency, as evidenced by Cronbach’s alpha values predominantly over 0.80, reinforces the tool’s reliability. This uniformity underscores the PAM’s robustness in measuring patient activation across various demographics and conditions. This reliability is vital for the tool’s use in both clinical settings and large-scale population health studies.

Construct validity, established through correlations with other health measures, demonstrates the PAM’s effectiveness in capturing the essence of patient engagement. This aspect is crucial for tailoring interventions and policies to enhance patient activation and, consequently, health outcomes. Studies like Bomba et al. [18] and Eyles et al. [21] illustrate how PAM scores correlate with meaningful health-related outcomes such as depressive symptoms, quality of life, and locus of control. These correlations are crucial for establishing the relevance of the PAM in predicting and influencing health behaviors and outcomes.

While content validity is less frequently reported, where available, the studies that do address this aspect, like Kosar et al. [30], show that the PAM’s items are considered relevant and reflective of the patient activation construct. Cross-cultural adaptation of the PAM was successfully implemented and validated across different countries, with good representation of European and Asian languages, demonstrating its flexibility and applicability globally. The adherence and complete reporting of the translation methodology also ensured the validity of the translated instrument, thus avoiding problems with conceptual, item, and semantic equivalence [53]. Furthermore, the high levels of reliability, as measured with Cronbach’s alpha, across these translated versions of the PAM seem to imply a uniform understanding of a patient’s activity and disease self-management. However, the emergence of multifactor structures in some cultural contexts indicates that patient activation may be conceptualized differently across cultures, although whether the organization of items into the factors concurred with theoretically acceptable domains was not discussed in the respective reports [17,24,47,48]. This finding underscores the need for cultural sensitivity and adaptability in the application of the PAM because cultural context does impact on people’s interpretation of questionnaire items, and hence future studies may be directed toward understanding the cross-cultural understanding of patient activation and its impact on PAM outcomes.

Beyond establishing reliability and construct validity, validation studies of the PAM have delved into its clinical utility. The instrument’s ability to predict health-related behaviors, outcomes, and healthcare utilization is a critical aspect of its practical application. The research consistently indicates that higher levels of patient activation, as measured by the PAM, are associated with more proactive health management behaviors and improved health outcomes [54]. The predictive validity of the PAM is exemplified by its capacity to anticipate patient behaviors, such as proactive health management and adherence to treatment plans [55,56]. Moreover, higher PAM scores have consistently been associated with improved health outcomes, including reduced healthcare utilization and improved overall quality of life [57,58,59]. This predictive power enables healthcare providers to identify individuals at risk for suboptimal outcomes and tailor interventions to meet specific patient needs. Additionally, the clinical utility of the PAM extends to resource allocation and personalized intervention strategies, making it an indispensable asset for fostering patient engagement, shared decision-making, and ultimately improving the efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare delivery [10,60,61]. This broad applicability supports the instrument’s ability to measure patient activation as a universal construct, possibly transcending specific health conditions and patient demographics.

Patient activation can be conceptualized as an element under the broader frameworks of patient self-management, which also encompasses concrete actions taken toward bettering the health of oneself and interactions with the care team. Wagner’s chronic care model organizes related concepts to describe the stakeholders and factors that participate in chronic disease care, specifically that of an informed, activated patient with productive interactions with a proactive care team against the context of a supportive community [62]. This indicates the ongoing paradigmatic shift away from a paternalistic care model toward a patient–physician partnership in care [63,64,65,66]. The latter then relies on active communication and engagement from the attending physician, so as to activate the patients toward self-management of disease and uptake of health behaviors [67,68]. Thus, measuring patient activation through tools such as the PAM is paramount in the care models of today.

Another tool that was recently developed and validated, which sought to measure patient activation, is the Consumer Health Activation Index (CHAI) [69]. This tool was developed as the authors positioned the PAM as being less appropriate for administration in populations with lower health literacy based on item readability. Moreover, the proprietary nature of the PAM restricts its use. The CHAI is a 10-item questionnaire on a 6-point Likert scale, with a recommended single-factor solution for simpler interpretation and parsimony in a clinical setting. The CHAI has been validated in other populations, such as in Australia and South Korea, and used in various settings [12,70,71,72]. No validation study comparing the reliability, reading level, or differential of both instruments head-on has been conducted and is thus much warranted. This will inform the indication of use for the respective instruments and ensure reciprocal validity between the two scales.

In sum, several notable limitations in the PAM studies were identified. Firstly, there is a notable scarcity of PAM validation studies involving the general population [8,50], and the tool’s variable reliability among specific subgroups—such as older adults and individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds—casts doubt on its universal applicability. As countries increasingly focus on social prescribing and more effectively addressing the social needs of their populations [73,74], exploring and understanding this aspect becomes a critical area for research. Second, the lack of comprehensive reporting on content validity in some studies poses a challenge in fully understanding the scope of the PAM tool. As aforementioned, the variability in factor structures across different translations suggests a need for further research to understand these differences better. Future studies should aim to address the identified limitations, including the exploration of content validity more comprehensively (as outlined by the COSMIN guidelines) and examining the tool’s applicability in broader and more diverse populations as health care moves toward activating not just patients but individuals in the community.

5. Conclusions

The PAM is a reliable and valid tool for assessing patient engagement in health care. A total of 39 validation and reliability studies were reviewed, and the studies demonstrate the application of the PAM across various cultural contexts, as well as the PAM’s ability to correlate with health outcomes relevant to patient-centered health care. Expanding its validation among the general population and other settings would be crucial steps in fully realizing its potential in improving population-wide healthcare delivery and outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12111079/s1, Table S1. Full search strategy for the various databases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.X.N.; methodology, Q.X.N., M.Y.Q.L., Y.Y.T., C.O., C.E.L. and J.T.; formal analysis, Q.X.N., M.Y.Q.L., Y.Y.T., A.S.P.T. and C.O.; investigation, Q.X.N., M.Y.Q.L., Y.Y.T., A.S.P.T. and C.O.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.X.N., M.Y.Q.L. and Y.Y.T.; writing—review and editing, Q.X.N., M.Y.Q.L., Y.Y.T., A.S.P.T., C.O., J.T. and C.E.L.; supervision, J.T. and C.E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Self-Care Interventions for Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/self-care#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Hibbard, J.H.; Cunningham, P.J. How Engaged are Consumers in Their Health and Health Care, and Why Does It Matter? Center for Studying Health System Change: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, G.; Rega, M.L.; Casasanta, D.; Graffigna, G.; Damiani, G.; Barello, S. The association between patient activation and healthcare resources utilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2022, 210, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.G.; Pandit, A.; Rush, S.R.; Wolf, M.S.; Simon, C.J. The role of patient activation in preferences for shared decision making: Results from a national survey of US adults. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paukkonen, L.; Oikarinen, A.; Kähkönen, O.; Kaakinen, P. Patient activation for self-management among adult patients with multimorbidity in primary healthcare settings. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Mahoney, E.R.; Tusler, M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Mahoney, E.R.; Stock, R.; Tusler, M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 1443–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Kaur, P.; Yap, C.W.; Heng, B.H. Psychometric Properties of the Patient Activation Measure in Community-Dwelling Adults in Singapore. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2022, 59, 00469580221100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngooi, B.X.; Packer, T.L.; Kephart, G.; Warner, G.; Koh, K.W.L.; Wong, R.C.C.; Lim, S.P. Validation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) among adults with cardiac conditions in Singapore. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janamian, T.; Greco, M.; Cosgriff, D.; Baker, L.; Dawda, P. Activating people to partner in health and self-care: Use of the Patient Activation Measure. Med. J. Aust. 2022, 216, S5–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Lai, J.; Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2197–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Jung, H.S. Measuring health activation among foreign students in South Korea: Initial evaluation of the feasibility, dimensionality, and reliability of the Consumer Health Activation Index (CHAI). Int. J. Adv. Cult. Technol. 2020, 8, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; De Vet, H.C. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, C.B.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L.; Ostelo, R.W.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: A scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acquati, C.; Hibbard, J.H.; Miller-Sonet, E.; Zhang, A.; Ionescu, E. Patient activation and treatment decision-making in the context of cancer: Examining the contribution of informal caregivers’ involvement. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 16, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, Y.-H.; Yi, C.-H.; Ham, O.-K.; Kim, B.-J. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the “Patient Activation Measure 13” (PAM13-K) in patients with osteoarthritis. Eval. Health Prof. 2015, 38, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrom, N.H.; Ramli, A.S.; Isa, M.R.; Baharudin, N.; Sham, S.F.B.; Yassin, M.S.M.; Hamid, H.A. Validity and reliability of the Patient Activation Measure® (PAM®)-13 Malay version among patients with Metabolic Syndrome in primary care. Malays. Fam. Physician Off. J. Acad. Fam. Physicians Malays. 2020, 15, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bomba, F.; Markwart, H.; Mühlan, H.; Menrath, I.; Ernst, G.; Thyen, U.; Schmidt, S. Adaptation and validation of the German Patient Activation Measure for adolescents with chronic conditions in transitional care: PAM® 13 for Adolescents. Res. Nurs. Health 2018, 41, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenk-Franz, K.; Hibbard, J.H.; Herrmann, W.J.; Freund, T.; Szecsenyi, J.; Djalali, S.; Steurer-Stey, C.; Sönnichsen, A.; Tiesler, F.; Storch, M. Validation of the German version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-D) in an international multicentre study of primary care patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, T.L.; Lipsitz, S.; Scanlan, M.; Yu, S.P.; Lindros, M.E.; Leung, W.Y.; Adelman, J.; Bates, D.W.; Dykes, P.C. Patient activation related to fall prevention: A multisite study. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2020, 46, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, J.; Ferreira, M.; Mills, K.; Lucas, B.; Robbins, S.; Williams, M.; Lee, H.; Appleton, S.; Hunter, D. Is the Patient Activation Measure a valid measure of osteoarthritis self-management attitudes and capabilities? Results of a Rasch analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowles, J.B.; Terry, P.; Xi, M.; Hibbard, J.; Bloom, C.T.; Harvey, L. Measuring self-management of patients’ and employees’ health: Further validation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) based on its relation to employee characteristics. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 77, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Bonanomi, A.; Lozza, E.; Hibbard, J. Measuring patient activation in Italy: Translation, adaptation and validation of the Italian version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-I). BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, S.M.; Idris, I.B.; Sharip, S.; Bahari, R.; Jahan, N. The Malay Version of Patient Activation Measure: An Instrument for Measuring Patient Engagement in Healthcare. Sains Malays. 2020, 49, 2487–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx, R.J.; Spreeuwenberg, M.D.; Drewes, H.W.; Ruwaard, D.; Baan, C.A. How to measure population health: An exploration toward an integration of valid and reliable instruments. Popul. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Mahoney, E.R.; Stockard, J.; Tusler, M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv. Res. 2005, 40, 1918–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.; Carter, M.; Hayden, C.; Dzierzon, R.; Morales, J.; Snow, L.; Butler, J.; Bateman, K.; Samore, M. Psychometric assessment of the patient activation measure short form (PAM-13) in rural settings. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, A.A.; Venkatesan, P.; Phansopkar, P.A. Translation and Validation of Patient Activation Measure (PAM [R]-13) in Kannada Language. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2020, 9, 2981–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kephart, G.; Packer, T.L.; Audulv, Å.; Warner, G. The structural and convergent validity of three commonly used measures of self-management in persons with neurological conditions. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosar, C.; Besen, D.B. Adaptation of a patient activatıon measure (PAM) into Turkish: Reliability and validity test. Afr. Health Sci. 2019, 19, 1811–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjo, L.; Dias, V.; Nunes, C.; Paiva, D.; Mahoney, B. Translation and validation of the patient activation measure in Portuguese people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Med. Port. 2018, 31, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, C.J.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Memory, K.E.; Palmer, J.; Smith, A.C. Reliability and validity of the patient activation measure in kidney disease: Results of rasch analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Chung, M.L.; Schuman, D.L.; Biddle, M.J.; Mudd-Martin, G.; Miller, J.L.; Hammash, M.; Schooler, M.P.; Rayens, M.K.; Feltner, F.J. Psychometric Properties of the Patient Activation Measure in Family Caregivers of Patients with Chronic Illnesses. Nurs. Res. 2023, 72, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnezi, R.; Glasser, S. Psychometric properties of the hebrew translation of the patient activation measure (PAM-13). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnezi, R.; Glasser, S.; Shalev, H.; Sheiber, A.; Reuveni, H. Patient activation, depression and quality of life. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maindal, H.T.; Sokolowski, I.; Vedsted, P. Translation, adaptation and validation of the American short form Patient Activation Measure (PAM13) in a Danish version. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melby, K.; Nygård, M.; Brobakken, M.F.; Gråwe, R.W.; Güzey, I.C.; Reitan, S.K.; Vedul-Kjelsås, E.; Heggelund, J.; Tchounwou, P.B. Test-retest reliability of the patient activation measure-13 in adults with substance use disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moljord, I.E.O.; Lara-Cabrera, M.L.; Perestelo-Pérez, L.; Rivero-Santana, A.; Eriksen, L.; Linaker, O.M. Psychometric properties of the Patient Activation Measure-13 among out-patients waiting for mental health treatment: A validation study in Norway. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijman, J.; Hendriks, M.; Brabers, A.; de Jong, J.; Rademakers, J. Patient activation and health literacy as predictors of health information use in a general sample of Dutch health care consumers. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Malley, D.; Dewan, A.A.; Ohman-Strickland, P.A.; Gundersen, D.A.; Miller, S.M.; Hudson, S.V. Determinants of patient activation in a community sample of breast and prostate cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, T.L.; Kephart, G.; Ghahari, S.; Audulv, Å.; Versnel, J.; Warner, G. The Patient Activation Measure: A validation study in a neurological population. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prey, J.E.; Qian, M.; Restaino, S.; Hibbard, J.; Bakken, S.; Schnall, R.; Rothenberg, G.; Vawdrey, D.K.; Creber, R.M. Reliability and validity of the patient activation measure in hospitalized patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 2026–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademakers, J.; Nijman, J.; van der Hoek, L.; Heijmans, M.; Rijken, M. Measuring patient activation in The Netherlands: Translation and validation of the American short form Patient Activation Measure (PAM13). BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmaderer, M.; Pozehl, B.; Hertzog, M.; Zimmerman, L. Psychometric properties of the patient activation measure in multimorbid hospitalized patients. J. Nurs. Meas. 2015, 23, 128E–141E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolasky, R.L.; Green, A.F.; Scharfstein, D.; Boult, C.; Reider, L.; Wegener, S.T. Psychometric properties of the patient activation measure among multimorbid older adults. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 46, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepleman, L.; Rutter, M.-C.; Hibbard, J.; Johns, L.; Wright, D.; Hughes, M. Validation of the patient activation measure in a multiple sclerosis clinic sample and implications for care. Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 1558–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, M.A.; Esmaeili Nadimi, A.; Bazmandegan, G.; Zakeri, M.; Dehghan, M. Psychometric evaluation of chronic patients using the Persian version of patient activation measure (PAM). Eval. Health Prof. 2023, 46, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Jiang, R.; Zhou, M.; Wu, L.; Tian, B.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, F. Measuring patient activation in Chinese patients with hypertension and/or diabetes: Reliability and validity of the PAM13. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 5967–5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zill, J.M.; Dwinger, S.; Kriston, L.; Rohenkohl, A.; Härter, M.; Dirmaier, J. Psychometric evaluation of the German version of the patient activation measure (PAM13). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrubka, Z.; Vékás, P.; Németh, P.; Dobos, Á.; Hajdu, O.; Kovács, L.; Gulácsi, L.; Hibbard, J.; Péntek, M. Validation of the PAM-13 instrument in the Hungarian general population 40 years old and above. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Countries. Available online: https://www.who.int/countries/ (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-I.; Luck, L.; Jefferies, D.; Wilkes, L. Challenges in adapting a survey: Ensuring cross-cultural equivalence. Nurse Res. 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmers, C.L.G. The Relationship between the Patient Activation Measure, Future Health Outcomes, and Health Care Utilization among Patients with Diabetes. Doctoral Dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Arden, M.; Hoo, Z.H.; Wildman, M. Understanding patient activation and adherence to nebuliser treatment in adults with cystic fibrosis: Responses to the UK version of PAM-13 and a think aloud study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, W.; Wan, L.-h. Association between patient activation and medication adherence in patients with stroke: A cross-sectional study. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 722711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haj, O.; Lipkin, M.; Kopylov, U.; Sigalit, S.; Magnezi, R. Patient activation and its association with health indices among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2022, 15, 17562848221128757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, M.E. Decreasing Preventable Emergency Department Visits Using the Patient Activation Measure; Salisbury University: Salisbury, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zakeri, M.A.; Dehghan, M.; Ghaedi-Heidari, F.; Zakeri, M.; Bazmandegan, G. Chronic patients’ activation and its association with stress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life: A survey in southeast Iran. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6614566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mullins, C.D.; Novak, P.; Thomas, S.B. Personalized strategies to activate and empower patients in health care and reduce health disparities. Health Educ. Behav. 2016, 43, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reistroffer, C.L. Patient Activation: An Examination of the Relationship between Care Management with Patient Activation-Customized Coaching and Patient Outcomes. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, E.H. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff. Clin. Pract. 1998, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, L.P. Death, Dying and the Ending of Life, Volumes I and II; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Siegler, M. The progression of medicine: From physician paternalism to patient autonomy to bureaucratic parsimony. Arch. Intern. Med. 1985, 145, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, J.J. Doctor-patient relationship: From medical paternalism to enhanced autonomy. Singap. Med. J. 2002, 43, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Karazivan, P.; Dumez, V.; Flora, L.; Pomey, M.-P.; Del Grande, C.; Ghadiri, D.P.; Fernandez, N.; Jouet, E.; Las Vergnas, O.; Lebel, P. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: A conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.M.; Cabana, M.D.; Nan, B.; Gong, Z.M.; Slish, K.K.; Birk, N.A.; Kaciroti, N. The clinician-patient partnership paradigm: Outcomes associated with physician communication behavior. Clin. Pediatr. 2008, 47, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deber, R.B. Physicians in health care management: 7. The patient-physician partnership: Changing roles and the desire for information. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1994, 151, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.S.; Smith, S.G.; Pandit, A.U.; Condon, D.M.; Curtis, L.M.; Griffith, J.; O’Conor, R.; Rush, S.; Bailey, S.C.; Kaplan, G. Development and validation of the consumer health activation index. Med. Decis. Mak. 2018, 38, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flight, I.; Harrison, N.J.; Symonds, E.L.; Young, G.; Wilson, C. Validation of the Consumer Health Activation Index (CHAI) in general population samples of older Australians. PEC Innov. 2023, 3, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, M.S.; Serper, M.; Opsasnick, L.; O’Conor, R.M.; Curtis, L.; Benavente, J.Y.; Wismer, G.; Batio, S.; Eifler, M.; Zheng, P. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the US outbreak: A cross-sectional survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haff, N.; Lauffenburger, J.C.; Morawski, K.; Ghazinouri, R.; Noor, N.; Kumar, S.; Juusola, J.; Choudhry, N.K. The accuracy of self-reported blood pressure in the Medication adherence Improvement Support App for Engagement–Blood Pressure (MedISAFE-BP) trial: Implications for pragmatic trials. Am. Heart J. 2020, 220, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Low, L.L.; Lu, S.Y.; Lee, C.E. Implementation of social prescribing: Lessons learnt from contextualising an intervention in a community hospital in Singapore. Lancet Reg. Health-West. Pac. 2023, 35, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapo, E.; Johansson, E.; Jonsson, F.; Hörnsten, Å.; Lundgren, A.S.; Nilsson, I. Critical components of social prescribing programmes with a focus on older adults-a systematic review. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2023, 41, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).