Association between Alcohol Use Disorder and Suicidal Ideation Using Propensity Score Matching in Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Sample and Design

2.2. Independent Variables

AUDIT-K

2.3. Dependent Variables

Suicidal Ideation

2.4. Control Variables

2.4.1. Socioeconomic and Demographic Factors

2.4.2. Health Status and Behavioral Factors

2.5. Analytical Approach and Statistics

2.6. Propensity Score Matching

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants before and after PSM

3.2. General Characteristics of Subjects Included for Analysis after PSM

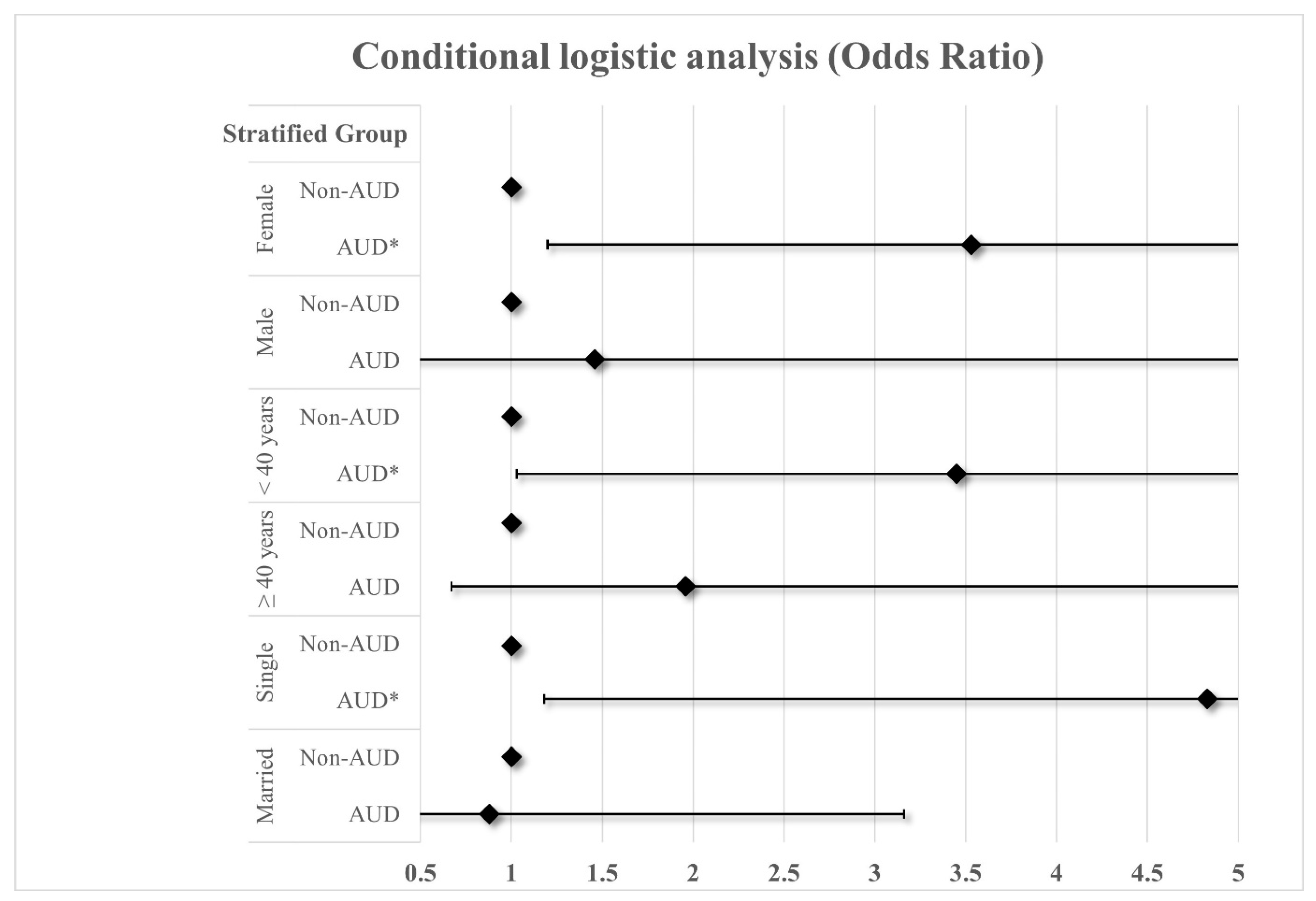

3.3. Stratified PS Matched Conditional Logistic of SI

3.4. Stratified PS Matched Conditional Logistic of SI by Sex or Age

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Witkiewitz, K.; Litten, R.; Leggio, L. Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Scafato, E.; Gandin, C.; Ghirini, S.; Matone, A.; Alcol, O.N. Alcohol in Europe: Epidemiology, policies and sustainable health targets to fill the gaps of prevention. Nutr. Cur. 2024, 3, e140. [Google Scholar]

- Raninen, J.; Karlsson, P.; Callinan, S.; Norström, T. Different measures of alcohol use as predictors of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder among adolescents—A cohort study from Sweden. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2024, 257, 111265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.F.; Heilig, M.; Perez, A.; Probst, C.; Rehm, J. Alcohol use disorders. Lancet 2019, 394, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization Economic Cooperation Development (OECD). OECD Health Statistics 2022; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rim, S.J.; Hahm, B.-J.; Seong, S.J.; Park, J.E.; Chang, S.M.; Kim, B.-S.; An, H.; Jeon, H.J.; Hong, J.P.; Park, S. Prevalence of mental disorders and associated factors in Korean Adults: National Mental Health Survey of Korea 2021. Psychiatry Investig. 2023, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tower, S.; Banaag, A.; Adams, R.S.; Janvrin, M.L.; Koehlmoos, T.P. Analysis of alcohol use and alcohol use disorder trends in US active-duty service women. J. Women’s Health, 2024; Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Lee, B.H. The Epidemiology of Alcohol Use Disorders. J. Korean Diabetes 2012, 13, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Statistics Korea. Korean Social Trends 2019; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, J.; Lee, C.; Kweon, Y.; Lee, K.; Lee, H.; Jo, S.; Kim, H. Twelve-month prevalence and correlates of hazardous drinking: Results from a community sample in Seoul. Korea J. Korean Acad. Addict. Psychiatry 2011, 15, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Levit, J.D.; Meyers, J.L.; Georgakopoulos, P.; Pato, M.T. Risk for alcohol use problems in severe mental illness: Interactions with sex and racial/ethnic minority status. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 325, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Kim, K.V.; Lasserre, A.M.; Orpana, H.; Bagge, C.; Roerecke, M.; Rehm, J. Sex-specific association of alcohol use disorder with suicide mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e241941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, M. The Copenhagen City Heart Study. Østerbroundersøgelsen. A book of tables with data from the first examination (1976-78) and a five year follow-up (1981-83). Scand. J. Soc. Med. Suppl. 1989, 41, 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, G.; Nock, M.K.; Abad, J.M.H.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.A.; Alonso, J.; Andrade, L.H.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Beautrais, A.; Bromet, E. Twelve-month prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 21777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yip, P.S.F.; Chang, S.-S.; Wong, P.W.C.; Law, F.Y.W. Association between changes in risk factor status and suicidal ideation incidence and recovery. Crisis 2015, 36, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderoost, F.; van der Wielen, S.; van Nunen, K.; Van Hal, G. Employment loss during economic crisis and suicidal thoughts in Belgium: A survey in general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e691–e697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Korea. Suicide Ideations; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Korea. Suicide Rate; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Korea. High-Risk Drinking Rates; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.H.; Kim, K.T.; You, J.Y. Chungcheongnam-do Mental Health Survey; Chungcheongnam-do Public Agency for Social Service: Hongseong-gun, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J. Prevalence and related risk factors of problem drinking in Korean adult population. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2018, 19, 389–397. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, W.-Y.; Chang, T.-G.; Chang, C.-C.; Chiu, N.-Y.; Lin, C.-H.; Lane, H.-Y. Suicide ideation among outpatients with alcohol use disorder. Behav. Neurol. 2022, 2022, 4138629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orui, M.; Kawakami, N.; Iwata, N.; Takeshima, T.; Fukao, A. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and its relationship to suicidal ideation in a Japanese rural community with high suicide and alcohol consumption rates. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2011, 16, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C. How to approach to suicide prevention. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 2019, 62, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.P.; Lee, H.K.; Cho, M.J.; Park, J.I.; Dawson, D.A.; Grant, B.F. Alcohol use disorders, nicotine dependence, and co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders in the United States and South Korea—A cross-national comparison. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 36, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, A.C.; Ohlsson, H.; Mościcki, E.; Crump, C.; Sundquist, J.; Kendler, K.S.; Sundquist, K. Alcohol use disorder and non-fatal suicide attempt: Findings from a Swedish National Cohort Study. Addiction 2022, 117, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, T.; Cohen, G.; Le Foll, B.; Rehm, J.; Hassan, A.N. The effect of pre-existing alcohol use disorder on the risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder: Results from a longitudinal national representative sample. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2020, 46, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Park, K.-W.; Kim, M.-S.; Ryu, K.-Y.; Paek, S.-Y.; Park, W.-J.; Oh, M.-K. Relationship between Household Type and Problematic Alcohol Drinking in University Students. Korean J. Fam. Pract. 2023, 13, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Understanding Alcohol Use Disorder; NIAAA: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, G.A.; Oh, M.A.; Lee, N.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, N.H. Social Network-Based Support Measures for Addiction Recovery; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2018; pp. 1–263. [Google Scholar]

- Larance, B.; Campbell, G.; Peacock, A.; Nielsen, S.; Bruno, R.; Hall, W.; Lintzeris, N.; Cohen, M.; Degenhardt, L. Pain, alcohol use disorders and risky patterns of drinking among people with chronic non-cancer pain receiving long-term opioid therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 162, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherübl, H. Alcohol use and gastrointestinal cancer risk. Visc. Med. 2020, 36, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.J.; Lee, S.Y. A Study on Poossible Causes of Suicide and Its Countermeasures; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, K.R.; Bagge, C.L. Suicidal Behavior: Links Between Alcohol Use Disorder and Acute Use of Alcohol. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2019, 40, arcr.v40.1.02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.Y.; Ko, H.J.; Kim, C.O.; Kim, B.R. Risk Factors of Suicide Attempt in Male Patients with Alcohol Dependence. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2013, 52, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, D.; Spittal, M.J.; Patton, G.; Pirkis, J. Life stress and suicidal ideation in Australian men—Cross-sectional analysis of the Australian longitudinal study on male health baseline data. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flensborg-Madsen, T.; Knop, J.; Mortensen, E.L.; Becker, U.; Sher, L.; Grønbæk, M. Alcohol use disorders increase the risk of completed suicide—Irrespective of other psychiatric disorders. A longitudinal cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 167, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, J.; Tiret, B.; Gallini, A.; Gandia, P.; Arbus, C.; Mathur, A.; Bougon, E. Suicide Attempts: How Does the Acute Use of Alcohol Affect Suicide Intent? Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2020, 50, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziółkowski, M.; Czarnecki, D.; Chodkiewicz, J.; Gąsior, K.; Juczyński, A.; Biedrzycka, A.; Gruszczyńska, E.; Nowakowska-Domagała, K. Suicidal thoughts in persons treated for alcohol dependence: The role of selected demographic and clinical factors. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 258, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.M.; Jeon, S.-W.; Cho, S.J.; Shin, Y.C.; Park, J.-H. Comparison of the factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempt: A comprehensive examination of stress, view of life, mental health, and alcohol use. Asian J. Psychiatry 2021, 65, 102844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, K.R.; Li, Y.; Meldrum, S.; Duberstein, P.R.; Conwell, Y. The role of drinking in suicidal ideation: Analyses of Project MATCH data. J. Stud. Alcohol 2003, 64, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintanilla, M.E.; Tampier, L.; Sapag, A.; Gerdtzen, Z.; Israel, Y. Sex differences, alcohol dehydrogenase, acetaldehyde burst, and aversion to ethanol in the rat: A systems perspective. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 293, E531–E537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, M.E.; Terry-McElrath, Y.M.; Kloska, D.D.; Schulenberg, J.E. High-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: Prevalence, frequency, and developmental change. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, J.Y.; Smith, M.M.; Sherry, S.B.; Seno, M.; Moore, M.L.; Stewart, S.H. Alcohol use and death by suicide: A meta-analysis of 33 studies. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2022, 52, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaemo, V.N.; Fawehinmi, T.O.; D’Arcy, C. Risk of suicide ideation in comorbid substance use disorder and major depression. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timko, C.; DeBenedetti, A.; Moos, B.S.; Moos, R.H. Predictors of 16-year mortality among individuals initiating help-seeking for an alcoholic use disorder. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006, 30, 1711–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Edwards, A.C.; Kendler, K.S.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Healthcare utilisation prior to suicide in persons with alcohol use disorder: National cohort and nested case–control study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 217, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, D.H.; Manor, O.; Eisenbach, Z.; Neumark, Y.D. The Protective Effect of Marriage on Mortality in a Dynamic Society. Ann. Epidemiol. 2007, 17, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yi, Z. Marital status and all-cause mortality rate in older adults: A population-based prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.K. Epidemiology of Alcohol Use Disorders and Alcohol Policy. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2019, 58, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Medical Status Internal Data for 2016 of Health Insurance Alcohol Use Disorder by Age and Gender; Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service: Gwangju, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, K.; Batra, A.; Fauth-Bühler, M.; Hoch, E. German guidelines on screening, diagnosis and treatment of alcohol use disorders. Eur. Addict. Res. 2017, 23, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2022 Alcohol Statistical Databook; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Non-AUD | AUD | p-Value | Total | Non-AUD | AUD | p-Value | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Total | 823 | 100.0 | 710 | 86.3 | 113 | 13.7 | 255 | 100.0 | 204 | 80.0 | 51 | 20.0 | ||

| Sex | <0.0001 | 0.750 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 390 | 47.4 | 312 | 80.0 | 78 | 20.0 | 150 | 58.8 | 119 | 79.3 | 31 | 20.7 | ||

| Female | 433 | 52.6 | 398 | 91.9 | 35 | 8.1 | 105 | 41.2 | 85 | 81.0 | 20 | 19.0 | ||

| Age | <0.0001 | 0.987 | ||||||||||||

| 20–29 | 135 | 16.4 | 96 | 71.1 | 39 | 28.9 | 54 | 21.1 | 42 | 77.8 | 12 | 22.2 | ||

| 30–39 | 155 | 18.8 | 130 | 83.9 | 25 | 16.1 | 56 | 22.0 | 46 | 82.1 | 10 | 17.9 | ||

| 40–49 | 193 | 23.5 | 158 | 81.9 | 35 | 18.1 | 79 | 31.0 | 63 | 79.7 | 16 | 20.3 | ||

| 50–59 | 179 | 21.7 | 172 | 96.1 | 7 | 3.9 | 30 | 11.8 | 24 | 80.0 | 6 | 20.0 | ||

| 60–69 | 161 | 19.6 | 154 | 95.7 | 7 | 4.3 | 36 | 14.1 | 29 | 80.6 | 7 | 19.4 | ||

| Residency region | 0.051 | 0.054 | ||||||||||||

| City unit | 666 | 80.9 | 567 | 85.1 | 99 | 14.9 | 217 | 85.1 | 169 | 77.9 | 48 | 22.1 | ||

| Town unit | 157 | 19.1 | 143 | 91.1 | 14 | 8.9 | 38 | 14.9 | 35 | 92.1 | 3 | 7.9 | ||

| Marital status | <0.0001 | 0.095 | ||||||||||||

| Single (including separated, divorced) | 249 | 30.3 | 193 | 77.5 | 56 | 22.5 | 99 | 38.8 | 74 | 74.7 | 25 | 25.3 | ||

| Married | 574 | 69.7 | 517 | 90.1 | 57 | 9.9 | 156 | 61.2 | 130 | 83.3 | 26 | 16.7 | ||

| Family income | 0.574 | 0.297 | ||||||||||||

| <200 | 96 | 11.7 | 76 | 79.2 | 20 | 20.8 | 36 | 14.1 | 32 | 88.9 | 4 | 11.1 | ||

| 200–500 | 416 | 50.5 | 358 | 86.1 | 58 | 13.9 | 127 | 49.8 | 98 | 77.2 | 29 | 22.8 | ||

| ≥500 | 311 | 37.8 | 276 | 88.7 | 35 | 11.3 | 92 | 36.1 | 74 | 80.4 | 18 | 19.6 | ||

| Education level | 0.099 | 0.546 | ||||||||||||

| ≤Middle school | 73 | 8.9 | 69 | 94.5 | 4 | 5.5 | 18 | 7.1 | 16 | 88.9 | 2 | 11.1 | ||

| High school | 314 | 38.2 | 269 | 85.7 | 45 | 14.3 | 99 | 38.8 | 77 | 77.8 | 22 | 22.2 | ||

| ≥College | 436 | 53.0 | 372 | 85.3 | 64 | 14.7 | 138 | 54.1 | 111 | 80.4 | 27 | 19.6 | ||

| Type of occupation | 0.162 | 0.913 | ||||||||||||

| Economically inactive | 55 | 6.7 | 46 | 83.6 | 9 | 16.4 | 20 | 7.8 | 17 | 85.0 | 3 | 15.0 | ||

| Self-employment | 119 | 14.5 | 109 | 91.6 | 10 | 8.4 | 26 | 10.2 | 20 | 76.9 | 6 | 23.1 | ||

| Blue collar | 322 | 39.1 | 281 | 87.3 | 41 | 12.7 | 108 | 42.4 | 87 | 80.6 | 21 | 19.4 | ||

| White collar | 327 | 39.7 | 274 | 83.8 | 53 | 16.2 | 101 | 39.6 | 80 | 79.2 | 21 | 20.8 | ||

| Anxiety disorder | <0.0001 | 0.679 | ||||||||||||

| No | 713 | 86.6 | 640 | 89.8 | 73 | 10.2 | 229 | 89.8 | 184 | 80.3 | 45 | 19.7 | ||

| Yes | 110 | 13.4 | 70 | 63.6 | 40 | 36.4 | 26 | 10.2 | 20 | 76.9 | 6 | 23.1 | ||

| Depression disorder | <0.0001 | 0.494 | ||||||||||||

| No | 687 | 83.5 | 626 | 91.1 | 61 | 8.9 | 234 | 91.8 | 186 | 79.5 | 48 | 20.5 | ||

| Yes | 136 | 16.5 | 84 | 61.8 | 52 | 38.2 | 21 | 8.2 | 18 | 85.7 | 3 | 14.3 | ||

| Variables | Suicidal Ideation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No | Yes | p-Value | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Total | 255 | 100.0 | 190 | 74.5 | 65 | 25.5 | |

| AUDIT-K | 0.073 | ||||||

| Non-AUD | 204 | 80.0 | 157 | 77.0 | 47 | 23.0 | |

| AUD | 51 | 20.0 | 33 | 64.7 | 18 | 35.3 | |

| Sex | 0.514 | ||||||

| Male | 150 | 58.8 | 114 | 76.0 | 36 | 24.0 | |

| Female | 105 | 41.2 | 76 | 72.4 | 29 | 27.6 | |

| Age | 0.000 | ||||||

| 20–29 | 54 | 21.2 | 44 | 81.5 | 10 | 18.5 | |

| 30–39 | 56 | 22.0 | 31 | 55.4 | 25 | 44.6 | |

| 40–49 | 79 | 31.0 | 56 | 70.9 | 23 | 29.1 | |

| 50–59 | 30 | 11.8 | 28 | 93.3 | 2 | 6.7 | |

| 60–69 | 36 | 14.1 | 31 | 86.1 | 5 | 13.9 | |

| Residency region | 0.899 | ||||||

| City unit | 217 | 85.1 | 162 | 74.7 | 55 | 25.3 | |

| Town unit | 38 | 14.9 | 28 | 73.7 | 10 | 26.3 | |

| Marital status | 0.010 | ||||||

| Single (including separated, divorced) | 99 | 38.8 | 65 | 65.7 | 34 | 34.3 | |

| Married | 156 | 61.2 | 125 | 80.1 | 31 | 19.9 | |

| Family income | 0.017 | ||||||

| <200 | 36 | 14.1 | 24 | 66.7 | 12 | 33.3 | |

| 200–500 | 127 | 49.8 | 88 | 69.3 | 39 | 30.7 | |

| ≥500 | 92 | 36.1 | 78 | 84.8 | 14 | 15.2 | |

| Education level | 0.458 | ||||||

| ≤Middle school | 18 | 7.1 | 13 | 72.2 | 5 | 27.8 | |

| High school | 99 | 38.8 | 78 | 78.8 | 21 | 21.2 | |

| ≥College | 138 | 54.1 | 99 | 71.7 | 39 | 28.3 | |

| Type of occupation | 0.119 | ||||||

| Economically inactive | 20 | 7.8 | 12 | 60.0 | 8 | 40.0 | |

| Self-employment | 26 | 10.2 | 23 | 88.5 | 3 | 11.5 | |

| Blue collar | 108 | 42.4 | 77 | 71.3 | 31 | 28.7 | |

| White collar | 101 | 39.6 | 78 | 77.2 | 23 | 22.8 | |

| Anxiety disorder | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 229 | 89.8 | 182 | 79.5 | 47 | 20.5 | |

| Yes | 26 | 10.2 | 8 | 30.8 | 18 | 69.2 | |

| Depression disorder | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 234 | 91.8 | 185 | 79.1 | 49 | 20.9 | |

| Yes | 21 | 8.2 | 5 | 23.8 | 16 | 76.2 | |

| Variables | Suicidal Ideation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| AUDIT-K | ||||

| Non-AUD | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| AUD | 1.82 | (0.94–3.53) | 2.40 * | (1.10–5.22) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.21 | (0.68–2.13) | 0.81 | (0.35–1.87) |

| Age | ||||

| 20–29 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 30–39 | 3.55 ** | (1.49–8.43) | 2.43 | (0.83–7.15) |

| 40–49 | 1.81 | (0.78–4.19) | 2.25 | (0.77–6.57) |

| 50–59 | 0.31 | (0.06–1.54) | 0.58 | (0.09–3.55) |

| 60–69 | 0.71 | (0.22–2.28) | 0.55 | (0.08–3.66) |

| Residency region | ||||

| City unit | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Town unit | 1.05 | (0.48–2.30) | 1.22 | (0.48–3.11) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (including separated, divorced) | 2.11 * | (1.19–3.74) | 1.50 | (0.63–3.62) |

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Family income | ||||

| <200 | 2.79 * | (1.14–6.83) | 1.96 | (0.56–6.80) |

| 200–500 | 2.47 ** | (1.25–4.89) | 2.09 | (0.93–4.69) |

| ≥500 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Education level | ||||

| ≤Middle school | 0.98 | (0.33–2.92) | 3.03 | (0.47–19.62) |

| High school | 0.68 | (0.37–1.26) | 1.00 | (0.48–2.10) |

| ≥College | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Type of occupation | ||||

| Economically inactive | 2.26 | (0.83–6.20) | 1.56 | (0.46–5.35) |

| Self-employment | 0.44 | (0.12–1.61) | 0.78 | (0.16–3.79) |

| Blue collar | 1.37 | (0.73–2.55) | 1.16 | (0.54–2.46) |

| White collar | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Anxiety disorder | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 8.71 *** | (3.57–21.26) | 2.73 | (0.89–8.41) |

| Depression disorder | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 12.08 *** | (4.22–34.61) | 5.30 * | (1.33–21.09) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.-M.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, M.-S.; Hong, J.-S.; Gu, B.-H.; Park, J.-H.; Choi, Y.-L.; Lee, J.-J. Association between Alcohol Use Disorder and Suicidal Ideation Using Propensity Score Matching in Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131315

Yang J-M, Kim J-H, Kim M-S, Hong J-S, Gu B-H, Park J-H, Choi Y-L, Lee J-J. Association between Alcohol Use Disorder and Suicidal Ideation Using Propensity Score Matching in Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea. Healthcare. 2024; 12(13):1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131315

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jeong-Min, Jae-Hyun Kim, Min-Soo Kim, Ji-Sung Hong, Bon-Hee Gu, Ju-Ho Park, Young-Long Choi, and Jung-Jae Lee. 2024. "Association between Alcohol Use Disorder and Suicidal Ideation Using Propensity Score Matching in Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea" Healthcare 12, no. 13: 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131315

APA StyleYang, J.-M., Kim, J.-H., Kim, M.-S., Hong, J.-S., Gu, B.-H., Park, J.-H., Choi, Y.-L., & Lee, J.-J. (2024). Association between Alcohol Use Disorder and Suicidal Ideation Using Propensity Score Matching in Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea. Healthcare, 12(13), 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131315