Mapping Quality Indicators to Assess Older Adult Health and Care in Community-, Continuing-, and Acute-Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Guidelines

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Identify existing QIs relevant to the health and care of older adults in community care, continuing care, and acute care;

- (2)

- Categorize the identified QIs based on key attributes to create a taxonomy to facilitate their selection and application.

2. Materials and Methods

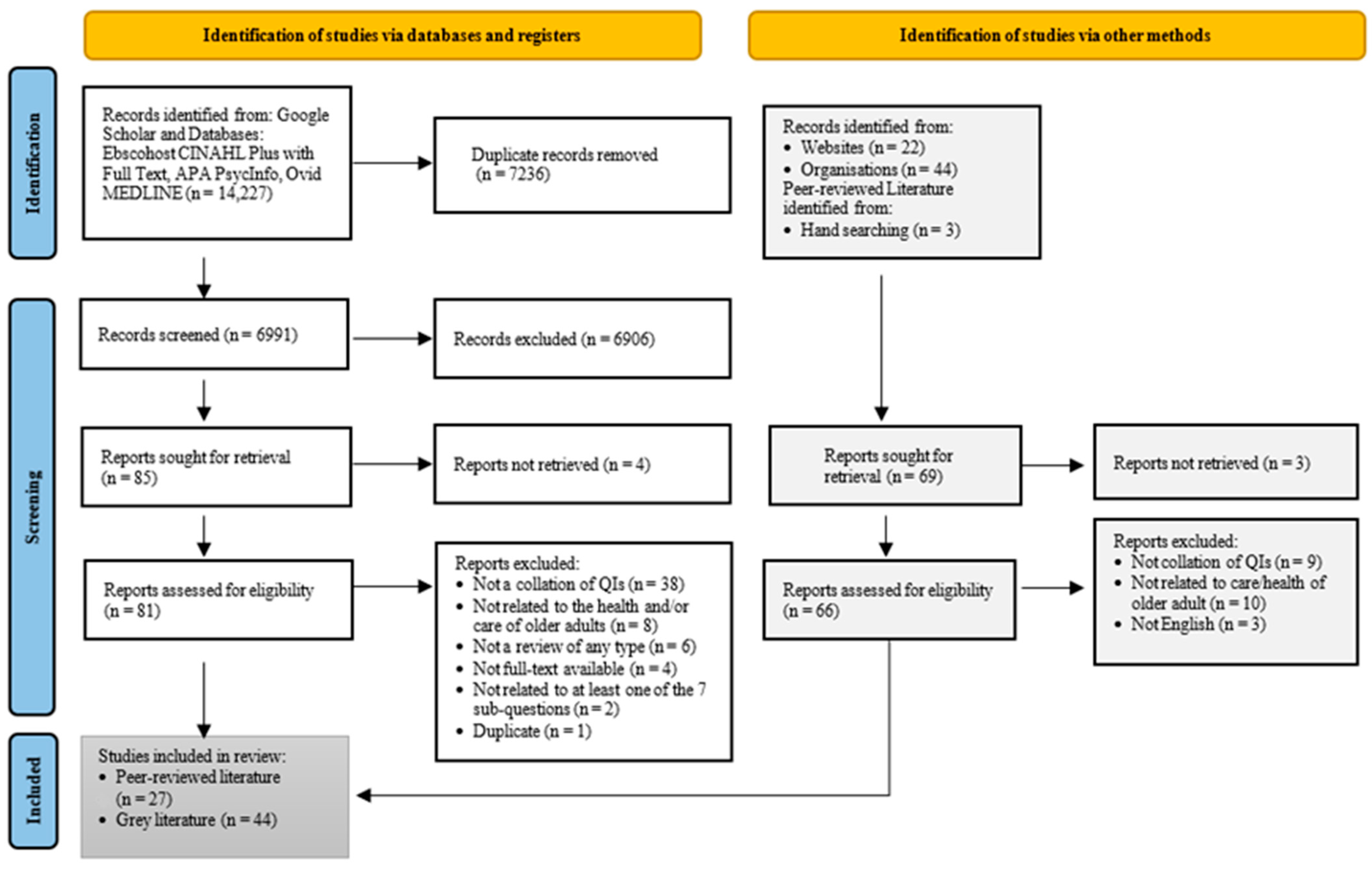

2.1. Search Strategies, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction and Coding

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

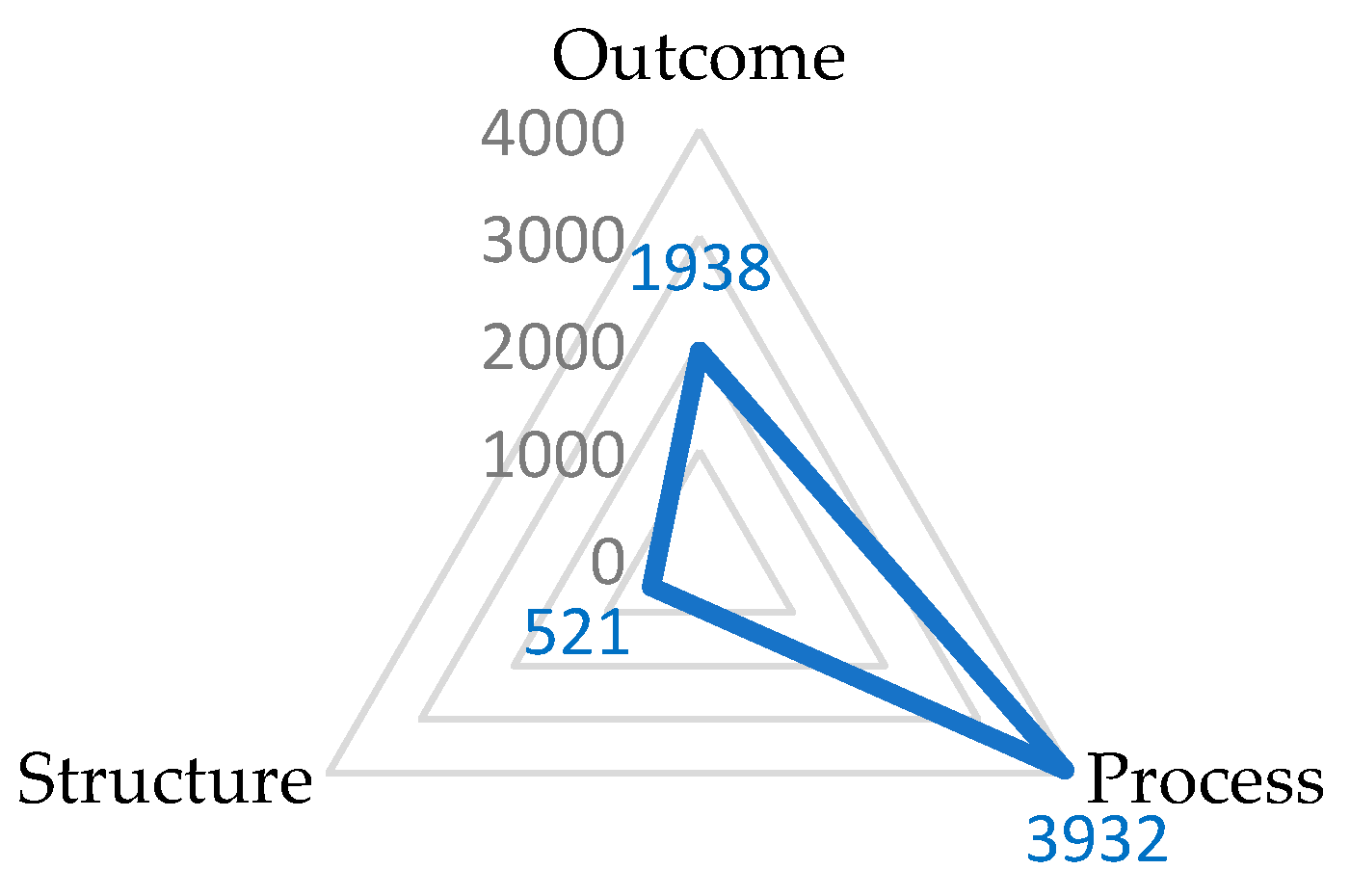

3.2. Quality Indicators’ Characteristics

3.2.1. Quality Indicators by Specific Setting

3.2.2. Domains Attributed to Quality Indicators

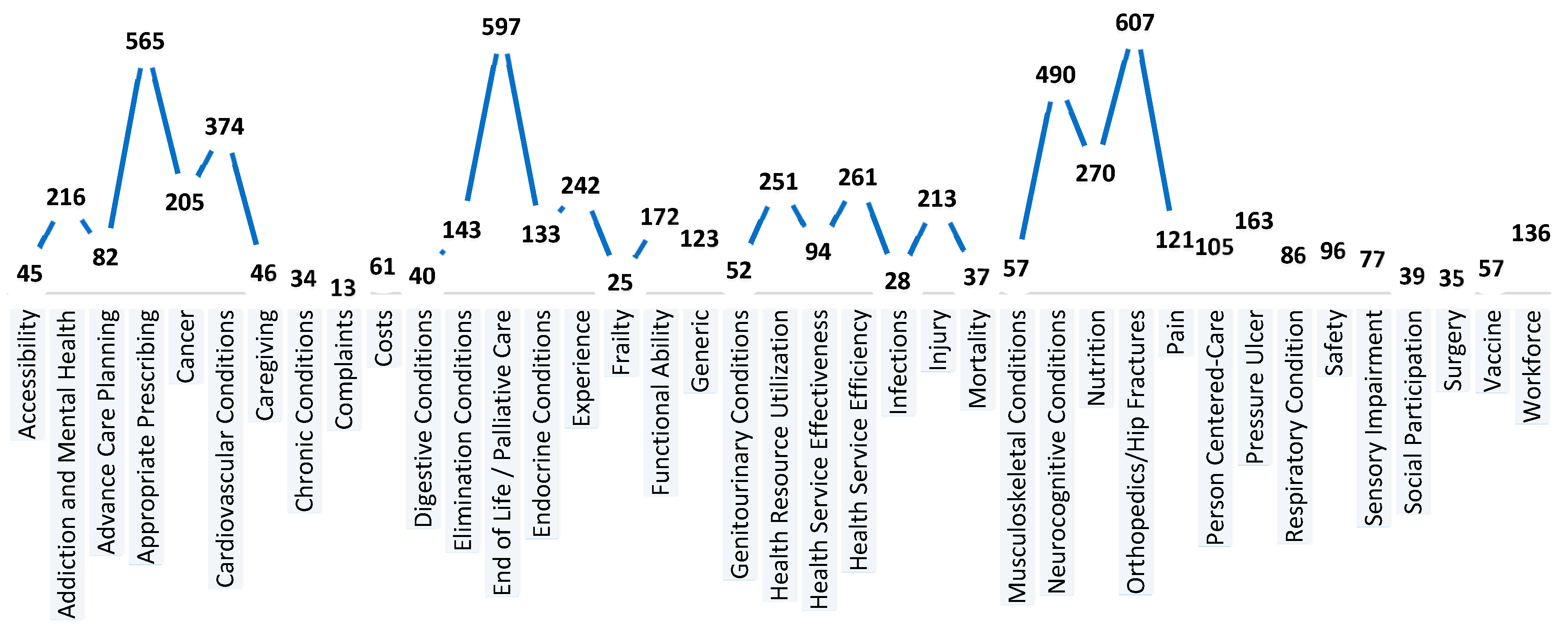

3.2.3. Quality Indicator Focus Area

3.2.4. Embracing the Quadruple Aims

3.3. Quality Indicators with Minimum Threshold: Description and Calculation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, K.; Lee, S.; Rowe, B.H.; Cummings, G.E.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.; Reid, R.C.; El-Bialy, R.; Bakal, J.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Anderson, C.; et al. Quality Indicators for Older Persons’ Transitions in Care: A Systematic Review and Delphi Process. Can. J. Aging 2022, 41, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, S. Living Longer within Ageing Societies. J. Popul. Ageing 2019, 12, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikos, D.; Selvaraj, K.; Vaidyanathasubramani, V.; Pandey, P. Empowering Patients to Choose Appropriate and Safe Hospital Services. Stud. Health Technol. 2016, 221, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorganci, E.; Sampson, E.L.; Gillam, J.; Aworinde, J.; Leniz, J.; Williamson, L.E.; Cripps, R.L.; Stewart, R.; Sleeman, K.E. Quality indicators for dementia and older people nearing the end of life: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 3650–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainz, J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality improvement. Int. J. Qual. Health C 2003, 15, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.; Holly, C.; Kahlil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an Umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeslee, S. The CRAAP test. Loex Q. 2004, 31, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Transforming Health with Integrated Care (THINC): Areas of Focus and Essential Elements. Available online: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/53008.html (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Donabedian, A. An Introduction to Quality Assurance in Health Care; Bashshur, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, A.; Clowes, M.; Preston, L.; Booth, A. Meeting the review family: Exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2019, 36, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Population Ageing. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Report.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Camp, P.G.; Cheung, W. Are We Delivering Optimal Pulmonary Rehabilitation? The Importance of Quality Indicators in Evaluating Clinical Practice. Phys. Ther. 2018, 98, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Egidio, V.; Sestili, C.; Lia, L.; Cianfanelli, S.; Backhaus, I.; Dorelli, B.; Ricciardi, M. Systematic Review of the Quality Indicators (QIs) to Evaluate the CCCN Approach in the Management of Oncologic Patients. Available online: https://www.ipaac.eu/res/file/outputs/wp10/quality-indicators-systematic-review-evaluation-comprehensive-cancer-care-network.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Pasman, H.R.W.; Brandt, H.E.; Deliens, L.; Francke, A.L. Quality Indicators for Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2009, 38, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidorenkov, G. Predictive Value of Treatment Quality Indicators on Outcomes in Patients with Diabetes; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Quentin, W.; Partanen, V.M.; Brownwood, I.; Klazinga, N. Measuring healthcare quality. In Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe: Characteristics, Effectiveness and Implementation of Different Strategies; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Mant, J. Process versus outcome indicators in the assessment of quality of health care. Int. J. Qual. Health C 2001, 13, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, S.J.; Naganathan, V.; Blyth, F.M. Aortic Aneurysm Trials in Octogenarians: Are We Really Measuring the Outcomes that Matter? Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26223531 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Alberta Government. Canadian Institute for Health Information—Long-Term Care Quality Indicator. Available online: https://open.alberta.ca/publications/cihi-long-term-care-quality-indicators (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Alberta Health. RAI-MDS 2.0 Quality Indicator Interpretation Guide. Available online: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/aa056894-c85f-4526-a3da-25cd64795082/resource/05bfbf33-070c-49d7-a4ce-1fc7857741cd/download/cc-cihi-rai-guide-2015.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2000).

- Alberta Health Services. Vital stats death data information [Tableau Dashboard]. Seniors Health, Community and Continuing Care; AHS: Edmonton, AB, Canada.

- Alberta Health Services. Community, Seniors, Addictions, & Mental Health [Tableau Dashboard]; AHS: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alberta Health Services. Quarterly Monitoring Measures, Quarterly Update 2017-18—FQ4. Available online: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/about/publications/ahs-pub-monitoring-measures-2017-18.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Alberta Senior Citizens’ Housing Association. Tableau Dashboard; ASCHA: Edmonton, AB, Canada.

- Amador, S.; Sampson, E.L.; Goodman, C.; Robinson, L.; Team, S.R. A systematic review and critical appraisal of quality indicators to assess optimal palliative care for older people with dementia. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines. Available online: https://caep.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/geri_ed_guidelines_caep_endorsed.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Angel-Garcia, D.; Martinez-Nicolas, I.; Salmeri, B.; Monot, A. Quality of Care Indicators for Hospital Physical Therapy Units: A Systematic Review. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzab261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrhenius, V.; Kiviniemi, K. Finland—Achieving Quality Long-Term Care in Residential Facilities. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=8120&langId=en (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Arslan, I.G.; Rozendaal, R.M.; van Middelkoop, M.; Stitzinger, S.A.G.; Van de Kerkhove, M.P.; Voorbrood, V.M.I.; Bindels, P.J.E.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Schiphof, D. Quality indicators for knee and hip osteoarthritis care: A systematic review. RMD Open 2021, 7, e001590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askari, M.; Wierenga, P.C.; Eslami, S.; Medlock, S.; de Rooij, S.E.; Abu-Hanna, A. Assessing Quality of Care of Elderly Patients Using the ACOVE Quality Indicator Set: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. National Aged Care Mandatory Quality Indicator Program Manual 1.0. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-11/national-aged-care-mandatory-quality-indicator-program-manual-1-0.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Baldwin, R.; Chenoweth, L.; dela Rama, M.; Wang, A.Y. Does size matter in aged care facilities? A literature review of the relationship between the number of facility beds and quality. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkett, E.; Martin-Khan, M.G.; Gray, L.C. Quality indicators in the care of older persons in the emergency department: A systematic review of the literature. Australas. J. Ageing 2017, 36, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Cardiovascular Quality Indicators. Available online: https://www.ccs.ca/images/Health_Policy/CCS_QualityIndicators.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pan-Canadian Primary Health Care Indicator Update Report. Available online: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/PHC_EMR_Content_Standard_V3.0_Business_View_EN.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Potentially Inappropriate Medication Prescribed to Seniors. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/indicators/potentially-inappropriate-medication-prescribed-to-seniors (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Caughey, G.; Lang, C.; Bray, S.; Moldovan, M.; Jorissen, R.; Wesselingh, S.; Inacio, M. International and National Quality and Safety Indicators for Aged Care; Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safet: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S.; Spooner, A.; Parker, C.; Jack, L.; Schnitker, L.; Beattie, E.; Yates, P.; MacAndrew, M. Clinical indicators of acute deterioration in persons who reside in residential aged care facilities: A rapid review. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2023, 55, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Progress Programme 2007–2013, Quality Care for Quality Aging: European Indicators for Home Health Care. Available online: http://www.synergia-net.it/uploads/attachment/2_1288867489.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Foong, H.Y.; Siette, J.; Jorgensen, M. Quality indicators for home- and community-based aged care: A critical literature review to inform policy directions. Australas. J. Ageing 2022, 41, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, M.; Sirois, M.J.; Gagnon, M.A.; Émond, M.; Bérubé, M.; Morin, M.; Moore, L. Identifying Quality Indicators for the Care of Hospitalized Injured Older Adults: A Scoping Review of the Literature. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Canada-New Brunswick Home and Community Care and Mental Health and Addictions Services Funding Agreement. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/health-agreements/shared-health-priorities/new-brunswick.html (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Griggs, K. Geriatric Nursing-Sensitive Indicators, a Framework for Delivering Quality Nursing Care for the Older Person: A Scoping Review. Doctoral Dissertation, Adelaide Nursing School, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Health, P. European Core Health Indicators (ECHI): Indicators and Data. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/indicators-and-data_en (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Health PEI One Island Health System. Health PEI Strategic Plan 2017–2020; Health PEI: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand. Health Quality & Safety Indicators. Available online: https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/Our-data/Publications-resources/Data-dictionary-working-file.xlsx (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Health Quality Council of Alberta. Review of Quality Assurance in Continuing Care Health Services in Alberta. Available online: https://hqca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Continuing_Care_FINAL_Report.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Healthcare Research and Quality. Review of Proposed Changes with ICD–10–CM/PCS Conversion of AHRQ Quality Indicators™ (QI). Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/11/26/2013-28282/review-of-proposed-changes-with-icd-10-cmpcs-conversion-of-quality-indicatorstm-qis (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Helsedirektoratet. Quality Indicators in Oral Health Care: A Nordic Project. Available online: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/quality-indicators-in-oral-health-care-a-nordic-project-proceedings-in-2012-2018/2019%20Nordic%20quality%20indicators%20oral%20health.pdf/_/attachment/inline/c901a3c8-259b-4484-96d5-34bdf5d85b33:3c3f67502008c978f39e5c739b4157d0b98dd25f/2019%20Nordic%20quality%20indicators%20oral%20health.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Hillen, J.B.; Vitry, A.; Caughey, G.E. Evaluating medication-related quality of care in residential aged care: A systematic review. Springerplus 2015, 4, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, A.M.; Milke, D.L.; Maisey, S.; Johnson, C.; Squires, J.E.; Teare, G.; Estabrooks, C.A. The Resident Assessment Instrument-Minimum Data Set 2.0 quality indicators: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICHOM Connect. Patient-Centered Outcome Measures: Older Person. Available online: https://www.ichom.org/portfolio/older-person/ (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Jajszczok, M.; Eastwood, C.A.; Quan, H.D.; Scott, L.D.; Gutscher, A.; Zhao, R.C. Health System Quality and Performance Indicators for Evaluating Home Care Programming: A Scoping Review. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2023, 35, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebeli, S.S.H.; Rezapour, A.; Rosenberg, M.; Moradi-Lakeh, M. Measuring universal health coverage to ensure continuing care for older people: A scoping review with specific implications for the Iranian context. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2021, 27, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joling, K.J.; van Eenoo, L.; Vetrano, D.L.; Smaardijk, V.R.; Declercq, A.; Onder, G.; van Hout, H.P.J.; van der Roest, H.G. Quality indicators for community care for older people: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kootenay Boundary Division of Family Practice. PMH/PCH QI Framework. Available online: https://divisionsbc.ca/sites/default/files/Divisions/Provincial/PMH%20QI%20Framework%203%20(ID%2096897).pdf (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Lee, K.E.C.; Sokas, C.M.; Streid, J.; Senglaub, S.S.; Coogan, K.; Walling, A.M.; Cooper, Z. Quality Indicators in Surgical Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorini, C.; Porchia, B.R.; Pieralli, F.; Bonaccorsi, G. Process, structural, and outcome quality indicators of nutritional care in nursing homes: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manitoba Health Seniors and Active Living. Manitoba Primary Care Quality Indicators Guide. Available online: https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/primarycare/providers/pin/docs/indicator_guide.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Mitchell, R.J.; Wijekulasuriya, S.; du Preez, J.; Lystad, R.; Chauhan, A.; Harrison, R.; Curtis, K.; Braithwaite, J. Population-level quality indicators of end-of-life-care in residential aged care setting: Rapid systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 116, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munea, A.M.; Alene, G.D.; Debelew, G.T. Quality of youth friendly sexual and reproductive health Services in West Gojjam Zone, north West Ethiopia: With special reference to the application of the Donabedian model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Service Digital. NHS Outcomes Framework Indicators—December 2020 Supplementary Release. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-outcomes-framework/december-2020-supplementary-release (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Quality Standards Topic Library. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/standards-and-indicators/quality-standards-topic-library (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- National Institute on Aging. Enabling the Future Provision of Long-Term Care in Canada. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c2fa7b03917eed9b5a436d8/t/5d9de15a38dca21e46009548/1570627931078/EnablingtheFutureProvisionofLong-TermCareinCanada.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- National Patient Safety Consortium. Patient Safety and Quality Priorities for Consortium Participants. Available online: https://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/en/toolsResources/Patient-Safety-Quality-Priorities-Snap-Shot/Documents/Canadian%20Scan_Final_English.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- National Quality Forum. Health and Well-Being 2015–2017. Available online: https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2017/04/Health_and_Well-Being_2015-2017_Final_Report.aspx (accessed on 16 February 2021).

- NHS Health Scotland. Development of Health and Social Care Inequality Indicators for Scotland. Available online: http://www.healthscotland.scot/media/2919/health-and-social-care-indicator-specifications.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2021).

- Nordic Medico Statistical Committee. Health and Health Care of the Elderly in the Nordic Countries—From a Statistical Perspective. Available online: https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1158392/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Office of the Seniors Advocate British Columbia. British Columbia Residential Care Facilities. Available online: https://www.seniorsadvocatebc.ca/app/uploads/sites/4/2018/01/QuickFacts2018-Summary.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Ontario Health. Ontario Health Indicator Library. Available online: http://indicatorlibrary.hqontario.ca/Indicator/Search/EN (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- OECD. Definitions for Health Care Quality Indicators 2016-2017 HCQI Data Collection; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Osinska, M.; Favez, L.; Zuniga, F. Evidence for publicly reported quality indicators in residential long-term care: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, K.; Marengoni, A.; Forjaz, M.J.; Jureviciene, E.; Laatikainen, T.; Mammarella, F.; Muth, C.; Navickas, R.; Prados-Torres, A.; Rijken, M.; et al. Multimorbidity care model: Recommendations from the consensus meeting of the Joint Action on Chronic Diseases and Promoting Healthy Ageing across the Life Cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Health Policy 2018, 122, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitzul, K.B.; Munce, S.E.P.; Perrier, L.; Beaupre, L.; Morin, S.N.; McGlasson, R.; Jaglal, S.B. Scoping review of potential quality indicators for hip fracture patient care. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of New Brunswick. Social Development Annual Report 2017–2018. 2018. Available online: https://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/sd-ds/pdf/AnnualReports/Departmental/AnnualReport2017-2018.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Rand, S.; Smith, N.; Jones, K.; Dargan, A.; Hogan, H. Measuring safety in older adult care homes: A scoping review of the international literature. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saskatchewan Health Quality Council. Quality Insight Provides Valuable Information to Saskatoon Health Region’s Long-Term Care Staff. Available online: https://www.hqc.sk.ca/news-events/hqc-news/quality-insight-provides-valuable-information-to-saskatoon-health-regions-long-term-care-staff (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Schneberk, T.; Bolshakova, M.; Sloan, K.; Chang, E.; Stal, J.; Dinalo, J.; Jimenez, E.; Motala, A.; Hempel, S. Quality Indicators for High-Need Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 3147–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spilsbury, K.; Hewitt, C.; Stirk, L.; Bowman, C. The relationship between nurse staffing and quality of care in nursing homes: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Healthy Aging Indicators. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310046601 (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Tran, A.; Nguyen, K.H.; Gray, L.; Comans, T. A Systematic Literature Review of Efficiency Measurement in Nursing Homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorian Department of Health & Human Services. Quality Indicators in Public Sector Residential Aged Care Services. Available online: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/residential-aged-care/quality-indicators-in-public-sector-residential-aged-care-services (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Wagner, A.; Schaffert, R.; Möckli, N.; Zúñiga, F.; Dratva, J. Home care quality indicators based on the Resident Assessment Instrument-Home Care (RAI-HC): A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welton, J.M. Business Intelligence and Nursing Administration. J. Nurs. Admin. 2014, 44, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Operational Description |

|---|---|

| Older Adults | Older adults were defined as “individuals 65 years of age and over.” Other terms included “aged”, “elderly”, and “seniors”. Indicators covering a broad range of ages were also included if age adjustment was used. |

| Quality Indicators | The article presented at least one quality indicator which focused on health care; health outcomes; caregiver’s health outcome; care experience; or the caregivers’ care experience, workforce, or finances. |

| Review Articles | Any type of review, including, but not limited to, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods systematic reviews; meta-analyses; meta-ethnography reviews; narrative reviews; meta-narrative reviews; update reviews; reviews of psychometric properties; umbrella reviews; literature reviews; integrative reviews; scoping reviews; critical reviews; Cochrane reviews; mapping reviews; or rapid reviews. |

| Settings/Contexts | Quality indicators were related to the following settings or contexts: (1) The 4 Ps (prevention, promotion, population, or public health) were used to indicate the prevention of disease or illness, health promotion, or population-based/public health measures. (2) Community or primary care referred to community health and primary healthcare. (3) Acute care was used to indicate an emergency or acute medical intervention and care, including emergency-related dispatch services, care, transport, and hospital care. (4) Continuing care was used to indicate home care, supported living (assisted living), or long-term care (nursing homes). |

| Focus Area | Practical Definition | Examples of Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | Relating to the ability to access information or care in a reasonable mode/language/setting/time, or within a reasonable distance, or equitable opportunities to receive necessary health services or outcomes |

|

| Addiction and Mental Health | Relating to addictive behaviours and/or emotional or psychological wellbeing |

|

| Advance Care Planning | Relating to the providing of instructions for future care decisions |

|

| Appropriate Prescribing | Relating to the avoidance of inappropriate medications, use of medications as indicated, and attention to side effects/risk–benefit ratio. |

|

| Cancer | Relating to the diagnosis or treatment of cancer |

|

| Cardiovascular Conditions | Relating to treatments or diseases of the cardiovascular system, such as those affecting the heart and blood vessels |

|

| Caregiving | Relating to the activity of regularly supporting an older adult spouse/parent/family member/friend/neighbour |

|

| Chronic Conditions | Relating to the treatment/management of conditions or diseases that require ongoing medical care |

|

| Complaints | Expressions regarding unsatisfactory or unacceptable events/occurrences and the associated actions taken to address the issue |

|

| Costs | Relating to the financial expenditures associated with healthcare services or delivery |

|

| Digestive Conditions | Relating to the intake and processing of foods, including the stomach, liver, and gallbladder (not including the pancreas, see Endocrine Conditions) |

|

| Elimination Conditions | Relating to the excretion of wastes by bladder or bowel, including continence, catheterization, and urinary-tract infections and treatments |

|

| End of life/Palliative care | Relating to terminal stage care and/or management of symptoms rather than cure |

|

| Endocrine Conditions | Relating to conditions/diseases of the endocrine glands, including the pancreas |

|

| Experience | Relating to patient/client/resident satisfaction or the experience of receiving care/service |

|

| Frailty | Relating to a state of increased vulnerability or decline (including in/dependence), in two or more domains |

|

| Functional Ability | Relating to the performance of tasks of normal life, including ADLs, IADLs, transferring, mobility, balance, and gait |

|

| Generic | Relating to broad focus; relevant for most patients or settings |

|

| Genitourinary Conditions | Relating to conditions or diseases of the urinary or reproductive systems |

|

| Health Equity | Relating to fair or equal opportunities to receive the necessary health services or outcomes given efforts to address avoidable differences based on population groups |

|

| Health Resource Utilization | Relating to the use (overuse or underuse) of services, facilities, or available resources |

|

| Health Service Effectiveness | Relating to achieving the desired outcome of a healthcare service or practice |

|

| Health Service Efficiency | Relating to the optimal use of resources |

|

| Infections | Relating to general invasion of a microorganism such as bacteria or viruses (system-specific infections are excluded, i.e., pneumonia) |

|

| Injury | Relating to damage resulting from an external force |

|

| Mortality | Relating to deaths within a population |

|

| Musculoskeletal Conditions | Relating to the diagnosis, treatment, or outcomes of diseases of the musculoskeletal system, such as arthritis and joint or connective tissue conditions or diseases (excluding osteoporosis or orthopaedics/hip fractures) |

|

| Neurocognitive Conditions | Relating to conditions or diseases of the brain affecting cognition, such as dementia, delirium, or learning disabilities |

|

| Nutrition | Relating to food and/or nutrient consumption for optimal health |

|

| Orthopedics/Hip Fractures | Relating to the diagnosis and/or treatment of diseases or injuries of the skeletal system, such as hip fractures |

|

| Pain | Relating to the occurrence or treatment of painful sensations |

|

| Person-centered Care | Relating to the involvement of patients/clients/residents in their own care and decision-making to ensure personalized care |

|

| Pressure Ulcer | Relating to the formation or treatment of a break of the skin/tissue |

|

| Respiratory Conditions | Relating to conditions or diseases of the respiratory system, including asthma, COPD, and pneumonia |

|

| Safety | Relating to harmful, unintended, or unfavourable result of a disease, treatment, or intervention |

|

| Sensory Conditions | Relating to conditions of the sensory systems, including sight, hearing, and proprioception |

|

| Surgery | Relating to operative procedures and post-operative outcomes of surgical specialties, excluding orthopaedic surgery |

|

| Vaccine | Relating to vaccinations to prevent infection by virus |

|

| Workforce | Relating to the numbers, safety, and workplace experience of the health system workforce |

|

| Settings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quadruple Aim | Focus Area | Acute Care | Community/ Primary Care | Continuing Care | Prevention/Promotion/ Population/ Public Health | Total | Percent |

| Aim 1: Improving Population Health | |||||||

| Accessibility | 12 | 20 | 12 | 1 | 45 | 1% | |

| Addiction and Mental Health | 19 | 100 | 74 | 23 | 216 | 3% | |

| Advance Care Planning | 64 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 82 | 1% | |

| Appropriate Prescribing | 100 | 312 | 145 | 8 | 565 | 9% | |

| Cancer | 70 | 106 | 2 | 27 | 205 | 3% | |

| Cardiovascular Conditions | 166 | 185 | 17 | 6 | 374 | 6% | |

| Caregiving | 3 | 15 | 27 | 1 | 46 | 1% | |

| Chronic Conditions | 4 | 25 | 1 | 4 | 34 | 1% | |

| Complaints | 3 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 13 | 0% | |

| Digestive Conditions | 19 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 40 | 1% | |

| Elimination Conditions | 13 | 52 | 78 | 0 | 143 | 2% | |

| End of life/Palliative care | 253 | 123 | 221 | 0 | 597 | 9% | |

| Endocrine Conditions | 15 | 108 | 9 | 1 | 133 | 2% | |

| Frailty | 2 | 9 | 12 | 2 | 25 | 0% | |

| Functional Ability | 12 | 52 | 105 | 3 | 172 | 3% | |

| Generic | 5 | 20 | 65 | 33 | 123 | 2% | |

| Genitourinary Conditions | 4 | 41 | 7 | 0 | 52 | 1% | |

| Health Service Effectiveness | 26 | 54 | 12 | 2 | 94 | 1% | |

| Infections | 13 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 28 | 0% | |

| Injury | 50 | 77 | 80 | 6 | 213 | 3% | |

| Mortality | 10 | 1 | 19 | 7 | 37 | 1% | |

| Musculoskeletal Conditions | 1 | 42 | 9 | 5 | 57 | 1% | |

| Neurocognitive Conditions | 82 | 243 | 161 | 4 | 490 | 8% | |

| Nutrition | 33 | 46 | 183 | 8 | 270 | 4% | |

| Orthopedics/Hip Fractures | 312 | 284 | 8 | 3 | 607 | 10% | |

| Pain | 23 | 34 | 64 | 0 | 121 | 2% | |

| Person-Centered Care | 15 | 23 | 66 | 1 | 105 | 2% | |

| Pressure Ulcer | 43 | 25 | 94 | 1 | 163 | 3% | |

| Respiratory Condition | 40 | 32 | 12 | 2 | 86 | 1% | |

| Safety | 17 | 11 | 66 | 2 | 96 | 2% | |

| Sensory Impairment | 8 | 57 | 8 | 4 | 77 | 1% | |

| Social Participation | 2 | 6 | 20 | 11 | 39 | 1% | |

| Surgery | 29 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 1% | |

| Vaccine | 4 | 21 | 18 | 14 | 57 | 1% | |

| Aim 2: Optimizing the Patient Experience | |||||||

| Experience | 43 | 79 | 118 | 2 | 242 | 4% | |

| Aim 3: Enhancing Provider Experience | |||||||

| Workforce | 20 | 24 | 78 | 14 | 136 | 2% | |

| Aim 4: Ensuring Sustainability | |||||||

| Costs | 2 | 21 | 34 | 4 | 61 | 1% | |

| Health Resource Utilization | 165 | 31 | 55 | 0 | 251 | 4% | |

| Health Service Efficiency | 67 | 58 | 135 | 1 | 261 | 4% | |

| Total | 1769 | 2360 | 2055 | 207 | 6391 | 100% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karimi-Dehkordi, M.; Hanson, H.M.; Kennedy, M.; Wagg, A. Mapping Quality Indicators to Assess Older Adult Health and Care in Community-, Continuing-, and Acute-Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Guidelines. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12141397

Karimi-Dehkordi M, Hanson HM, Kennedy M, Wagg A. Mapping Quality Indicators to Assess Older Adult Health and Care in Community-, Continuing-, and Acute-Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Guidelines. Healthcare. 2024; 12(14):1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12141397

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarimi-Dehkordi, Mehri, Heather M. Hanson, Megan Kennedy, and Adrian Wagg. 2024. "Mapping Quality Indicators to Assess Older Adult Health and Care in Community-, Continuing-, and Acute-Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Guidelines" Healthcare 12, no. 14: 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12141397

APA StyleKarimi-Dehkordi, M., Hanson, H. M., Kennedy, M., & Wagg, A. (2024). Mapping Quality Indicators to Assess Older Adult Health and Care in Community-, Continuing-, and Acute-Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Guidelines. Healthcare, 12(14), 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12141397