Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated changes in European healthcare systems, with a significant proportion of COVID-19 cases being managed on an outpatient basis in primary healthcare (PHC). To alleviate the burden on healthcare facilities, many European countries developed contact-tracing apps and symptom checkers to identify potential cases. As the pandemic evolved, the European Union introduced the Digital COVID-19 Certificate for travel, which relies on vaccination, recent recovery, or negative test results. However, the integration between these apps and PHC has not been thoroughly explored in Europe. Objective: To describe if governmental COVID-19 apps allowed COVID-19 patients to connect with PHC through their apps in Europe and to examine how the Digital COVID-19 Certificate was obtained. Methodology: Design and setting: Retrospective descriptive study in PHC in 30 European countries. An ad hoc, semi-structured questionnaire was developed to collect country-specific data on primary healthcare activity during the COVID-19 pandemic and the use of information technology tools to support medical care from 15 March 2020 to 31 August 2021. Key informants belong to the WONCA Europe network (World Organization of Family Doctors). The data were collected from relevant and reliable official sources, such as governmental websites and guidelines. Main outcome measures: Patient’s first contact with health system, governmental COVID-19 app (name and function), Digital COVID-19 Certification, COVID-19 app connection with PHC. Results: Primary care was the first point of care for suspected COVID-19 patients in 28 countries, and 24 countries developed apps to complement classical medical care. The most frequently developed app was for tracing COVID-19 cases (24 countries), followed by the Digital COVID-19 Certificate app (17 countries). Bulgaria, Italy, Serbia, North Macedonia, and Romania had interoperability between PHC and COVID-19 apps, and Poland and Romania’s apps considered social needs. Conclusions: COVID-19 apps were widely created during the first pandemic year. Contact tracing was the most frequent function found in the registered apps. Connection with PHC was scarcely developed. In future pandemics, connections between health system levels should be guaranteed to develop and implement effective strategies for managing diseases.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the organization of the health systems across Europe to provide medical care for COVID-19 patients [1]. Numerous primary care facilities have adopted remote consultations as a preferred method while reserving in-person appointments for patients with more severe or acute symptoms [2]. Technological solutions such as contact tracing applications (apps) and COVID-19 symptom checkers have become widely used tools to identify possible cases. However, their connection with the initial point of access in the healthcare system remains unclear. Various mobile apps have been developed by countries, private companies, and other entities to assist in healthcare [3,4]. While the use of apps in general has become widespread and their potential in detecting COVID-19 cases is promising, there is limited evidence available regarding the benefits of e-health, such as m-health and teleconsultation. Further research is necessary to enhance future interventions [5]. Previous studies have identified inequalities in the use of e-health, highlighting the need for measures to ensure universal and equitable access [6].

In Europe, many countries launched mobile contact-tracing apps, in line with the guidance from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control guidelines (ECDC) [7]. Functionalities varied across countries; some apps allowed for the exchange of information with apps from other countries [8]. However, the COVID-19 contact-tracing apps have not been widely adopted by the European populations [4,8,9].

Challenges remain in terms of expanding the use of digital tools and evaluating clinical care in the context of COVID-19 [8,10]. In July 2021, the European Union (EU) implemented the use of the EU Digital COVID-19 Certificate to travel from one state to another within the EU and affiliated countries (Supplementary File S1). This required demonstrating immunity to COVID-19 by vaccination, being recently cured of the disease, or having a negative COVID-19 test [11]. Countries have developed applications to issue the EU COVID-19 digital certificate almost automatically, thus reducing bureaucracy. The majority of COVID-19 cases have been treated in the community, and contact tracing was performed between public health and primary care depending on the country [4], but the connection among COVID-19 apps and primary healthcare (PHC) has not been described. The main aim of this study is to examine if governmental COVID-19 apps allowed COVID-19 patients to connect with PHC through their apps in Europe. The secondary aim was to examine how the Digital COVID-19 Certificate was obtained in mobile apps in Europe.

2. Methods

2.1. Design of the Study

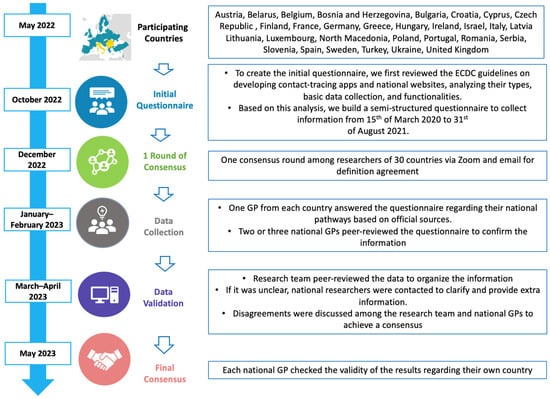

This study was retrospective and descriptive, and it was conducted starting in 2022 collecting information from 15 March 2020 to 31 August 2021 in 30 European countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participating countries and consensus on the questionnaire regarding the COVID-19 mobile apps and the connection with primary healthcare. Figure adapted from Ares-Blanco et al. [12].

2.2. Participants

Key informants who were linked to the working group (EGPRN) and the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) in Europe. These researchers belonged to 30 European countries (Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, North Macedonia, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom). Researchers received an open invitation through both networks to participate. We extended invitations to 80 contacts within these networks to participate. Of these, 46 general practitioners (GPs) agreed to serve as researchers, along with one public health expert who maintains close ties with local GPs, and one medical student collaborating with a participating GP. Among the participants, 42 GPs were actively practicing during the pandemic, while 35 GPs were affiliated with university departments.

2.3. Variables

The main variables examined in this study were the patient’s initial contact with the healthcare system, the existence of COVID-19 hotlines, the type of COVID-19 mobile app used, and the connection between the COVID-19 mobile app and PHC. The connection between the COVID-19 mobile app and PHC was defined as the ability to share information from the COVID-19 app with one’s PHC provider through means such as phone call, email, mobile messaging service, online appointments, or other relevant technologies in the case of suspected COVID-19. Please refer to Supplementary File S2 for detailed descriptions of these terms.

2.4. Data Collection

An ad hoc, semi-structured questionnaire intended to provide country-specific data on PHC activity in the COVID-19 pandemic was developed. The questionnaire also collected information on the use of information technology (IT) tools to support medical care (Table 1). To create the initial questionnaire, we first reviewed the ECDC guidelines on developing contact-tracing apps.

Table 1.

Questionnaire of the study.

Subsequently, the European Commission curated a list of contact-tracing and COVID-19 certificate apps from EU countries on a webpage. The core group (4 GPs, one of whom is also a public health doctor) then assessed the English-language information for these national websites, analyzing their types, basic data collection, and functionalities. Based on this analysis, a second version of the questionnaire was crafted. After collecting this information, it was shared with all key informants for their input, feedback, or suggestions to enhance the questionnaire. Two online meetings were organized to share comments until a consensus on the questionnaire items was reached. Following a month-long period, the final version of the questionnaire was completed. The national key informants received recommendations to collect information from relevant and reliable official sources (governmental websites and governmental guidelines are available in Supplementary File S3). One or two national key informants per country filled out the questionnaire; it was peer-reviewed by a different national researcher before sending it to the core group. They checked the national data to assure the data quality.

2.5. Analysis

Qualitative variables from the national questionnaires were organized and summarized. The core group performed an international peer review of all the national data collected. In the case of disagreement, the core group contacted the national key informants to clarify the description provided. Language was standardized for comparisons under the advice of all the key informants using English. All national key informants reviewed the results to confirm the findings. The STROBE guidelines of this study can be checked in Supplementary File S4.

3. Results

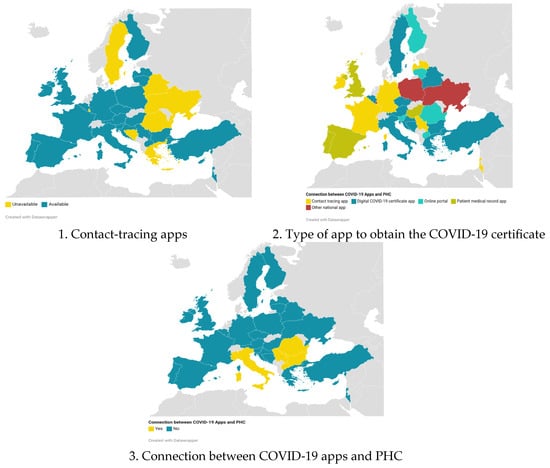

In 28 countries, primary care served as the initial point of contact for suspected COVID-19 patients, often in collaboration with other resources. Additionally, 25 countries established COVID-19 hotlines to provide information and address concerns related to the virus. Contact-tracing mobile apps were adopted by 24 countries (as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2). All countries developed additional functionalities tailored to their contact-tracing apps. The most commonly featured functionality, found in at least 12 countries, was providing health advice related to COVID-19, followed by a self-assessment of symptoms, available in 11 countries.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patient’s first contact with the health system, COVID-19 hotline, and governmental apps and connection between the apps and primary care in Europe.

Figure 2.

Situation of COVID-19 apps in Europe; map created with Datawrapper.

Turkey’s app sent notifications to local authorities in the case of non-compliance with isolation measures. Five countries (Bulgaria, Italy, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Romania) integrated COVID-19 mobile app information with PHC systems for each patient. In Bulgaria, GPs received an email notification if patients were identified as having a high risk for COVID-19 after a self-assessment test. GPs then decided how to proceed, either through a phone call or further examination. GPs could access the app using an e-signature to review patient results. In Italy (specifically the Campania region), the e-COVID app allowed patients to submit reports to their GPs. The Tests and Swabs app facilitated proactive care from GPs for COVID-19 patients in the Campania region. In North Macedonia, patient symptoms and COVID-19 test results were directly downloaded into an online portal and app called Moj Termin. This app was already in use by GPs before the pandemic, and GPs were required to fill out daily forms for their patients regarding COVID-19 symptoms. In Romania, patients could directly send reports to their GPs through the app. In Serbia, patients could complete a self-assessment test, and if the results indicated potential serious COVID-19 symptoms, they were recommended to schedule an examination with a doctor. Serbian citizens could use the national app to contact GPs or ask questions, which would then appear in the electronic health records of Serbian GPs, enabling direct communication with patients. Poland and Romania had apps that considered the social needs of the population. In Poland, isolated patients could contact social workers for support through the Polish app. The Romanian app was designed to assist Romanians living abroad in connecting with people when seeking help for their social support and translation service needs.

In Slovenia, the apps for COVID-19 testing and COVID-19 vaccination were able to transfer information to the electronic health record (EHR). However, there was no connection established between the clinical data from these apps and the EHR.

In Finland, there was an existing web portal called Omaolo that offered various functionalities such as sharing symptoms, booking PHC appointments, and communicating with healthcare providers. This portal was updated to include COVID-19 features for contacting PHC, but the specific functionalities varied across municipalities and regions. In June 2024, six apps were active.

Additionally, apps were developed for the issuance of the Digital COVID-19 Certificate. Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom used patient medical record to obtain the Digital COVID-19 Certificate. In Austria, citizens were required to independently upload their vaccine and recovery certificates into the official national Green Pass app. These certificates could be obtained from physicians, pharmacies, or accessed through the electronic health portal ELGA. In the Czech Republic, the online patient portal transferred COVID-19 vaccination information to an app, but without the functionalities of the portal. In France, Ireland, and Serbia, contact-tracing apps were utilized to obtain the Digital COVID-19 Certificate. Luxembourg, Poland, and Ukraine utilized the official governmental app for various procedures (such as taxes and form submissions) to acquire the certificate. In Germany, citizens were required to present their vaccination card at a pharmacy to obtain a paper QR code, which could then be scanned using two apps to obtain a digital certificate.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Results

PHC was the first point of care in 28 countries, sometimes in collaboration with other healthcare resources. In addition, 24 countries developed apps to complement classical medical care. The most commonly implemented app was for contact tracing, followed by the Digital COVID-19 Certificate app at the time of the data assessment. It is possible that this situation changed as the pandemic progressed. Bulgaria, Italy, Serbia, North Macedonia, and Romania allowed interoperability between PHC and the COVID-19 app. Additionally, only Poland and Romania’s COVID-19 apps took into consideration social needs.

4.2. Comparison with Prior Work

The pandemic presented a unique opportunity for innovation in healthcare service delivery. The majority of COVID-19 cases could be managed on an outpatient basis, without requiring hospital admission [13]. In Europe, several national COVID-19 apps were developed to disseminate information to the general population and COVID-19 patients. Previous studies have focused on app characteristics such as functionality, esthetics, and information quality [14,15], as well as the profile of app users [16,17], but little attention has been given to the role of these apps in connecting patients with the healthcare system.

It is crucial to highlight that, in addition to the applications developed specifically for managing the COVID-19 pandemic, there were other telemedicine applications (tele-apps) implemented by various companies that were operating even before the pandemic [18]. Tele-apps were designed to provide continuous remote health services, and they include features such as virtual medical consultations and prescription management and will remain relevant in the long term. In contrast, COVID-19 apps, quickly developed to respond to the urgency of the pandemic, had a temporary utility, and their relevance may decrease as the health crisis is controlled. This distinction is essential to understand the impact and future sustainability of these technologies in PHC, and IT tools served as the initial contact points for citizens and COVID-19 patients. However, during phases of lockdown in some European countries, there was a slight decrease in attendance at PHC facilities [19,20]. Despite citizens using apps and hotlines to seek guidance and medical advice, several challenges arose in providing an adequate and coordinated response to COVID-19 cases. Firstly, patients may receive conflicting advice depending on the channel they use, including the hotline, COVID-19 app, or PHC professionals. Secondly, there was a risk of information repetition by citizens or COVID-19 patients, leading to varying advice provided across different contact points. This issue was exacerbated by the overwhelming workload and shortage of staff at the public health, hospital, and PHC levels [21]. Proper coordination is essential to enhance effectiveness in the initial contact with the healthcare system [22]. Thirdly, data collected in IT tools should be integrated into electronic patient health records to ensure that valuable clinical and epidemiological information provided by citizens or patients is not missed. Currently, this integration was only considered in Italy and Serbia. Therefore, the lack of connection between PHC and IT tools contributes to fragmented care [23]. Interoperability of electronic records across all these services, including health IT tools, is crucial to provide comprehensive care and ensure patient safety. In this context, the OECD recommends robust information systems that deliver high-quality care, necessitating investments and active participation from stakeholders and the community [24].

COVID-19 apps were developed in response to the health crisis, but their cost-effectiveness, especially for contact tracing, still needs to be evaluated. There is a need for more evidence to understand their role in managing contact tracing, particularly as real-time usage in Europe was lower than expected [4,8]. Additionally, since many countries conducted contact tracing through PHC or public health systems, COVID-19 apps would need to be interoperable with PHC medical records to ensure efficient contact tracing and follow-up of COVID-19 cases [1,4]. While COVID-19 apps often included features for the self-assessment of symptoms and reporting results to public health authorities, they did not always address patient-specific needs [25]. They also failed to tackle the issue of digital illiteracy, which is more prevalent in vulnerable groups, as well as undocumented individuals [6]. Requiring identity card information for app registration could serve as a barrier for marginalized groups. Among the countries studied, only Serbia allowed patients to directly ask questions to their regular GP, and Poland provided the option to connect with a social worker. These aspects are crucial in addressing patient needs and delivering effective care, especially for vulnerable populations.

The characteristics and contents of the COVID-19 apps varied across Europe [4,25]. Although these apps are regulated by the medical devices legislation in the EU [26], further measure would be necessary to ensure a minimum set of functions and integration of app information within the existing healthcare system, particularly in PHC medical records and social services records. The lack of connection between the COVID-19 app’s clinical information and the healthcare system represents a missed opportunity to provide more integrated care and facilitate referrals to PHC facilities as the primary point of care in most European countries.

The Digital COVID-19 Certificate was initially introduced to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in international travel and other social activities. However, it is important to evaluate certain factors such as privacy concerns and social stratification [27]. One clear advantage of the Digital COVID-19 Certificate is that it promotes agreements between countries to adopt the same technology, allowing for its validity in the EU and other nations [11]. The process of obtaining the certificate has been integrated into the available IT tools in each country. It is positive that some countries enable patients to download the certificate directly through their existing patient apps, simplifying the process and allowing for additional functionalities to be added as the disease evolves. Serbia stands out as the only country to include a post-COVID-19 self-assessment questionnaire in their app, which is important in addressing the emergence of long COVID-19. However, only three countries utilized their patient record app to obtain the certificate, despite its effectiveness in expediting the response. Instead, nine countries opted to create a new app, which may inconvenience individuals by requiring them to use two different applications for the same purpose and could also incur additional costs for the countries. It would have been more advantageous if the digital certificate could have been integrated with other immunization records for international travel.

4.3. Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

From a research standpoint, this study highlights the need for further investigation into the effectiveness and usability of COVID-19 apps, as well as their integration with PHC systems and impact on health outcomes. It is essential to involve PHC professionals in the creation of app protocols through advisory committees, as they can provide valuable insights into patient-centered approaches. Having practicing PHC professionals as advisors can ensure that technology integration with healthcare systems enhances patient experience, reduces costs, and maintains confidentiality and usability [28]. This should be viewed as a long-term vision, recognizing the pivotal role that PHC plays in managing and responding to health crises like the ongoing pandemic. We suggest expanding the usage of apps with integrated access to patient medical records, encompassing both primary and secondary care records. It is advised that users can access at least their current medical conditions, ongoing treatments, and vaccination statuses. Furthermore, enabling appointment requests with the involved healthcare professionals would facilitate direct communication with the health center, ensuring comprehensive patient care.

In practice, this study emphasizes the importance of seamless integration between COVID-19 apps and PHC services to enable timely and appropriate care for suspected cases. Policymakers and healthcare providers should prioritize the development of robust and interoperable app solutions that effectively connect individuals with PHC services. Having an app connected to PHC can not only facilitate patient access to PHC, but also accessing their clinical information enhances patient safety if they are treated in a different region away from their home. Having the ability to expand the functions of that app where their medical history resides would allow us to trace COVID-19 contacts, follow-up and track long COVID symptoms, and monitor possible therapies that alleviate symptoms. At the same time, it is necessary to integrate the patient’s medical history with their social history by collecting social determinants, the patient’s social circle, care needs, and interventions carried out by social services.

The experience gained from the digital certificate implementation in the EU should have been utilized to improve citizens’ access to their health data and ensure their validity and usefulness across Europe, particularly in the context of cross-border policies. Overall, the findings call for collaborative efforts among researchers, policymakers, and healthcare providers to optimize the integration of COVID-19 apps with PHC, leading to improved patient outcomes and streamlined healthcare services.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

This study represents the first examination to date of how patients were able to connect with PHC services through governmental apps in Europe. The findings offer valuable insights into the opportunities and challenges associated with using apps to facilitate patient access to healthcare services. The study also provides practical examples of how these tools can be integrated into existing healthcare systems to enhance patient accessibility. The information presented in this study has been collected from publicly available and reliable online sources by local researchers who either worked in PHC or maintained close contact to GPs. Although the local researchers utilized trusted network resources to answer the questionnaires, it is possible that some relevant information may have been overlooked. In the case of the United Kingdom, the information is limited to England as no researchers were available in other regions. In Slovenia, a non-governmental app (CO-VID-Follower) was included due to its widespread usage among the population. This Slovenian app was developed by IT and healthcare professionals and incorporated information from governmental and public health sources. Although the COVID-Follower app was useful for the Slovenian population, it may have posed security risks since it was a non-governmental app. In Croatia, an app called “eCitizens” served as the patient portal for health records. Although the Croatian app allowed for information exchange between GPs and patients with mutual agreement, it was not specifically designed for COVID-19 and did not receive significant promotion or improvement during the pandemic.

The information was sourced exclusively from official channels, thereby excluding any critical aspects or malfunctions of the apps from the results. This limitation hinders a comprehensive evaluation of the apps’ value. While our primary objective was to describe the relationship between the apps and primary healthcare, the inclusion of additional functionalities would have enriched the dataset, allowing for a more comprehensive discussion of the apps’ limitations sourced from external channels. Additionally, as the data were collected retrospectively, only the latest version of each app available during the study period was considered.

5. Conclusions

Most European countries developed national COVID-19 apps, such as contact-tracing apps or Digital COVID-19 Certificate apps, at the onset of the pandemic. However, there was a lack of interoperability between these apps and primary healthcare information systems in most countries. This represents a missed opportunity to integrate the primary care sector, which has shouldered a significant burden in caring for patients with COVID-19, as a crucial pillar of the pandemic response. Future initiatives need to acknowledge the importance of the primary care sector and incorporate primary care into IT applications to ensure optimal and safe care for the majority of patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12141420/s1. File S1: Non-EU countries (and territories) that have joined the EU Digital COVID Certificate system. File S2: Definitions of each service and healthcare professional in this study. File S3: Sources of the COVID-19 Apps in each country. File S4: STROBE Statement.

Author Contributions

S.A.-B., M.G.-C., R.G.-B. and M.P.A.-P. were responsible for conceptualization, securing funding, developing the methodology, providing supervision, and drafting the original manuscript. S.A.-B., M.G.-C., I.G.L., L.R.D.R. and K.H. conducted formal analysis. All authors: L.F., H.L., L.M., N.P.L., Á.P., D.P., F.P., G.P., M.S., B.S., A.S., T.S., G.T., P.T. (Paula Tiili), P.T. (Péter Torzsa), K.V., B.V., K.V., S.V., L.A., R.A., M.B., S.B., E.B.-S., I.-C.B., A.Ć.D., M.D.P., P.-R.D., S.F., D.G., M.G.-J., M.H., K.H., O.I., S.I., M.J.-K., V.T.K., E.Ü., A.K., S.K., B.Ç.K., M.K., A.K.-K., L.K., K.N. and A.L.N. participated in the investigation process. S.A.-B. and R.G.-B. managed project administration. S.A.-B., M.G.-C., R.G.-B., I.G.L., L.R.D.R., M.P.A.-P. and K.H. collaborated on the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to the article and gave their approval for the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant of the European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN) (2022/01). The publication fee is supported by the Department of Primary Care Medicine, Center for Public Health, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. A.L.N. is funded by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Northwest London (ARC NWL), NIHR NWL Patient Safety Research Collaboration (NWL PSRC), with infrastructure support from NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid, Spain), ID PI-5030, approved on 25 October 2022. This ethical approval was obtained from all the participants. Additional ethical approval according to local laws was needed in Croatia (Ethical approval from the Ethics committee, School of Medicine, University of Zagreb: Ur. Broj: 380-59-10106-22-111/76, approved on 2 May 2022; Klasa: 641-01/22-02/01, approved on 2 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as no patients participated in this study. All the information collected was publicly available from official sources.

Data Availability Statement

Any data produced or examined during this study are available for sharing upon request. The primary data can be directly reviewed in the Supplementary Materials files. All methodologies were conducted in strict adherence to pertinent guidelines and regulations. For additional inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our heartfelt appreciation to the Department of Primary Care Medicine, Center for Public Health, Medical University of Vienna and K.H. for their generous support and provision of resources, which have been instrumental in the successful completion of this work. Furthermore, we would like to express our gratitude to all our colleagues who have made significant contributions to this research project. Their invaluable input, feedback, and support have played a crucial role in enhancing our understanding of the subject matter and enabling us to derive meaningful conclusions. Without their active involvement, this endeavor would not have been possible. We also thank Sherihane Bensemmane for her insight and comments to improve the final text and Laura Debouverie for her help in collecting Belgian data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. A.L.N.: The views expressed are those of the auth(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funding authorities had no influence in the conception, design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the study and related data. The funding authorities had additionally no influence in writing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

| Apps | Applications |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| EGPRN | European General Practice Research Network |

| EU | European Union |

| GP | General Practitioner |

| IT | Information technology |

| PHC | Primary healthcare |

| WONCA | World Organization of Family Doctors |

References

- Ares-Blanco, S.; Astier-Peña, M.P.; Gómez-Bravo, R.; Fernández-García, M.; Bueno-Ortiz, J.M. The role of primary care during COVID-19 pandemic: A European overview. Aten. Primaria 2021, 53, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Koh, G.C.H.; Car, J. COVID-19: A remote assessment in primary care. BMJ 2020, 368, m1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davalbhakta, S.; Advani, S.; Kumar, S.; Agarwal, V.; Bhoyar, S.; Fedirko, E.; Misra, D.P.; Goel, A.; Gupta, L.; Agarwal, V. A Systematic Review of Smartphone Applications Available for Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the Assessment of their Quality Using the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS). J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Quevedo, C.; Scarpetti, G.; Webb, E.; Shuftan, N.; Williams, G.A.; Birk, H.O.; Jervelund, S.S.; Krasnik, A.; Vrangbæk, K. Effective Contact Tracing and the Role of Apps. Eurohealth 2020, 26, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R.F.; Figures, E.L.; Paddison, C.A.; Matheson, J.I.; Blane, D.N.; Ford, J.A. Inequalities in general practice remote consultations: A systematic review. BJGP Open 2021, 5, BJGPO.2021.0040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, N.; Helberger, N.; Weert, J.C.M. Differences in mobile health app use: A source of new digital inequalities? Inf. Soc. 2018, 34, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Mobile Applications in Support of Contact Tracing for COVID-19—A Guidance for EU EEA Member States; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Tech Guide; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Solna, Sweden, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Mobile Contact Tracing Apps in EU Member States. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/coronavirus-response/travel-during-coronavirus-pandemic/mobile-contact-tracing-apps-eu-member-states_en (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Blasimme, A.; Ferretti, A.; Vayena, E. Digital Contact Tracing Against COVID-19 in Europe: Current Features and Ongoing Developments. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 660823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesara, S.; Jonas, A.; Schulman, K. COVID-19 and Health Care’s Digital Revolution. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Digital COVID Certificate. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/coronavirus-response/safe-covid-19-vaccines-europeans/eu-digital-covid-certificate_en (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Ares-Blanco, S.; Guisado-Clavero, M.; Ramos Del Rio, L.; Gefaell Larrondo, I.; Fitzgerald, L.; Adler, L.; Assenova, R.; Bakola, M.; Bayen, S.; Brutskaya-Stempkovskaya, E.; et al. Clinical pathway of COVID-19 patients in primary health care in 30 European countries: Eurodata study. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2023, 29, 2182879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, D.F.; Mallen, C.; McKee, M. The impact of COVID-19 on primary care in Europe. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2021, 6, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahnbach, L.; Lehr, D.; Brandenburger, J.; Mallwitz, T.; Jent, S.; Hannibal, S.; Funk, B.; Janneck, M. Quality and Adoption of COVID-19 Tracing Apps and Recommendations for Development: Systematic Interdisciplinary Review of European Apps. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheisari, M.; Ghaderzadeh, M.; Li, H.; Taami, T.; Fernández-Campusano, C.; Sadeghsalehi, H.; Afzaal Abbasi, A. Mobile Apps for COVID-19 Detection and Diagnosis for Future Pandemic Control: Multidimensional Systematic Review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2024, 12, e44406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteveen, D.; de Pedraza, P. The Roles of General Health and COVID-19 Proximity in Contact Tracing App Usage: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e27892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritsema, F.; Bosdriesz, J.R.; Leenstra, T.; Petrignani, M.W.F.; Coyer, L.; Schreijer, A.J.M.; van Duijnhoven, Y.T.H.P.; van de Wijgert, J.H.H.M.; Schim van der Loeff, M.F.; Matser, A. Factors Associated with Using the COVID-19 Mobile Contact-Tracing App among Individuals Diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Observational Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e31099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sherif, D.M.; Abouzid, M.; Elzarif, M.T.; Ahmed, A.A.; Albakri, A.; Alshehri, M.M. Telehealth and Artificial Intelligence Insights into Healthcare during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2022, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitzle, L.; Schmidt, C.; Färber, F.; Huebl, L.; Wieler, L.H.; Ziese, T.; Heidemann, C. Perceived Access to Health Care Services and Relevance of Telemedicine during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coma, E.; Mora, N.; Méndez, L.; Benítez, M.; Hermosilla, E.; Fàbregas, M.; Fina, F.; Mercadé, A.; Flayeh, S.; Guiriguet, C.; et al. Primary care in the time of COVID-19: Monitoring the effect of the pandemic and the lockdown measures on 34 quality of care indicators calculated for 288 primary care practices covering about 6 million people in Catalonia. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobucci, G. COVID-19: Underfunding of health workforce left many European nations vulnerable, says commission. BMJ 2021, 372, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares-Blanco, S.; Astier-Peña, M.P.; Gómez-Bravo, R.; Fernández-García, M.; Bueno-Ortiz, J.M. Human resource management and vaccination strategies in primary care in Europe during COVID-19 pandemic. Aten. Primaria 2021, 53, 102132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future of Telemedicine; OECD Health Policy Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 1–41. ISBN 9789264840416. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, J.A.; Radin, J.M.; Quer, G.; Topol, E.J. Smartphone apps in the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisado-Clavero, M.; Ares-Blanco, S.; Ben Abdellah, L.D. Using mobile applications and websites for the diagnosis of COVID-19 in Spain. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2021, 39, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of THE COUNCIL of 5 April 2017 on Medical Devices, Amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and Repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EE; European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kofler, N.; Baylis, F. Passports Are a Bad Idea. Nature 2020, 581, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, H.; Johns, L. Interoperability of Electronic Health Records: A Physician-Driven Redesign. Manag. Care 2018, 27, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).