Spiritual Connectivity Intervention for Individuals with Depressive Symptoms: A Randomized Control Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Spirituality, Religion, and Depression

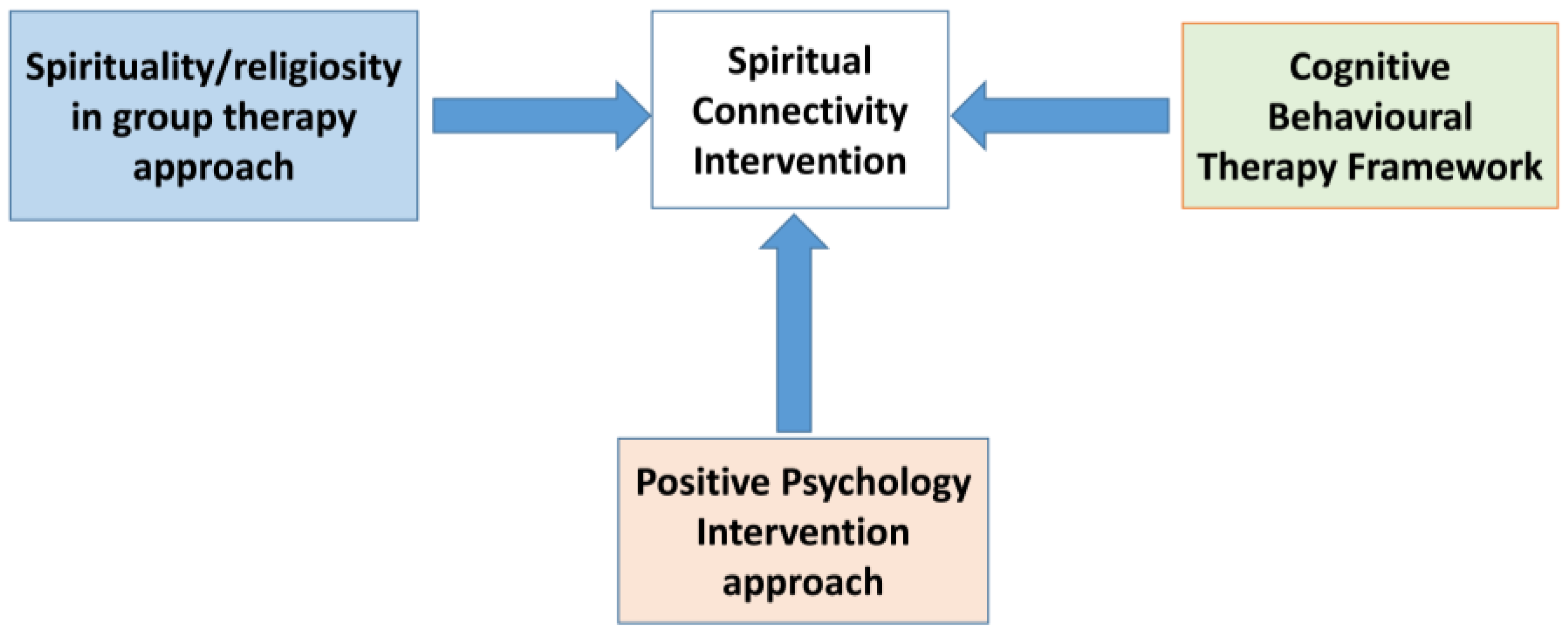

1.2. Therapeutic Components

1.3. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

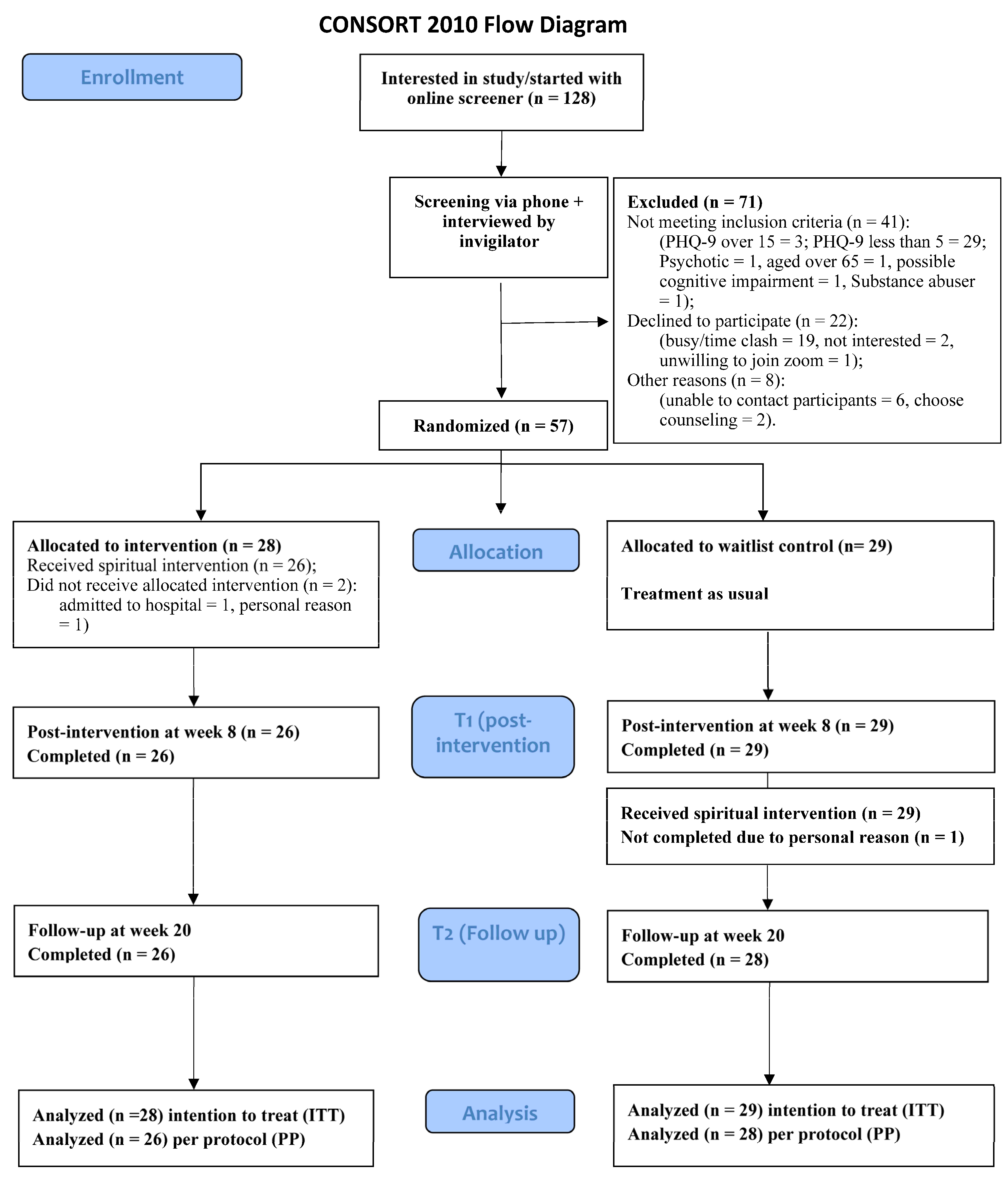

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Recruitment and Screening for Participants

2.5. Randomization, Allocation, and Blinding

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Interventions

2.8. Spirituality Connectivity Intervention Group (SCG)

2.9. Waitlist Control Group (WLG)

2.10. Treatment Fidelity

2.11. Data Collection

2.12. Outcome Measures

2.12.1. Primary Outcomes (Depression and Anxiety)

2.12.2. Secondary Outcomes

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Diagnosis of Participants

3.3. Number of Sessions Attended

3.4. Changes in Outcomes for Within-Group Comparisons

3.5. Changes in Outcomes for Between-Group Comparisons

3.6. Moderation Effect

3.7. Record of Daily Activities in the Mobile App

3.8. Sensitivity Analysis

3.9. Clinical Significance

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Depressive Disorder (Depression). 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Bromet, E.J. The Epidemiology of Depression Across Cultures. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Denson, L.A.; Dorstyn, D.S. Understanding Australian university students’ mental health help-seeking: An empirical and theoretical investigation. Aust. J. Psychol. 2018, 70, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Notivol, J.; Gracia-García, P.; Olaya, B.; Lasheras, I.; López-Antón, R.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021, 21, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSDG. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health (2020 May 13): United Nations Sustainable Development Group. 2020. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-need-action-mental-health (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Lake, J.; Turner, M.S. Urgent Need for Improved Mental Health Care and a More Collaborative Model of Care. Perm. J. 2017, 21, 17–024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiemke, C. Why Do Antidepressant Therapies Have Such a Poor Success Rate? Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, H.; Anheyer, D.; Cramer, H.; Dobos, G. Complementary therapies for clinical depression: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maoz, Z.; Henderson, E.A. The World Religion Dataset, 1945–2010: Logic, Estimates, and Trends. Int. Interact. 2013, 39, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.M. The Worlds Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography; Grim, B.J., Bellofatto, G.A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Feely, M.; Long, A. Depression: A psychiatric nursing theory of connectivity. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 16, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorajjakool, S.; Aja, V.; Chilson, B.; Ramírez-Johnson, J.; Earll, A. Disconnection, Depression, and Spirituality: A Study of the Role of Spirituality and Meaning in the Lives of Individuals with Severe Depression. Pastor. Psychol. 2008, 56, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaniol, L.; Bellingham, R.; Cohen, B.; Spaniol, S. The Recovery Workbook II: Connectedness; Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Boston University: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Warber, S.L.; Ingerman, S.; Moura, V.L.; Wunder, J.; Northrop, A.; Gillespie, B.W.; Durda, K.; Smith, K.; Rhodes, K.S.; Rubenfire, M. Healing the heart: A randomized pilot study of a spiritual retreat for depression in acute coronary syndrome patients. Explor. J. Sci. Health 2011, 7, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, S.; Starnino, V.; Canda, E. Spiritual Assessment in Mental Health Recovery. Community Ment. Health J. 2014, 50, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallot, R.D. Spirituality and religion in psychiatric rehabilitation and recovery from mental illness. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2001, 13, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, L.E.; Peteet, J.R.; Cook, C.C.H. Spirituality and mental health. J. Study Spiritual. 2020, 10, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.B.; McCullough, M.E.; Poll, J. Religiousness and Depression: Evidence for a Main Effect and the Moderating Influence of Stressful Life Events. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, N.; Tingle, A.; Tunmore, R.; Murrells, T. Implementing holistic practices in mental health nursing: A national consultation. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portnoff, L.; McClintock, C.; Lau, E.; Choi, S.; Miller, L. Spirituality Cuts in Half the Relative Risk for Depression: Findings From the United States, China, and India. Spiritual. Clin. Pract. 2017, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; Heywood-Everett, S.; Siddiqi, N.; Wright, J.; Meredith, J.; McMillan, D. Faith-adapted psychological therapies for depression and anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 176, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Captari, L.E.; Hook, J.N.; Hoyt, W.; Davis, D.E.; McElroy-Heltzel, S.E.; Worthington, E.L. Integrating clients’ religion and spirituality within psychotherapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.S.; Berglund, P.A.; Kessler, R.C. Patterns and Correlates of Contacting Clergy for Mental Disorders in the United States. Health Serv. Res. 2003, 38, 647–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, H.G.; McCullough, M.E.; Larson, D.B. Handbook of Religion and Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H.G.M.D. Religion and Depression in Older Medical Inpatients. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, R.; Koenig, H.G. Mental Disorders, Religion and Spirituality 1990 to 2010: A Systematic Evidence-Based Review. J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.C.W.; Fisher, A.T. Protestant spirituality and well-being of people in Hong Kong: The mediating role of sense of community. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2016, 11, 1253–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agli, O.; Bailly, N.; Ferrand, C. Spirituality and religion in older adults with dementia: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.W. Spirituality and Self-Esteem for Chinese People with Severe Mental Illness. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2010, 8, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueiro, B.P.; de Rezende Pinto, A.; Moreira-Almeida, A. Spirituality, religion, and mood disorders. In Handbook of Spirituality, Religion, and Mental Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chida, Y.; Schrempft, S.; Steptoe, A. A Novel Religious/Spiritual Group Psychotherapy Reduces Depressive Symptoms in a Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Relig. Health 2016, 55, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, K.; Aranda, M.P. Faith-Based Mental Health Interventions with African Americans: A Review. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2016, 26, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G.; Pearce, J.M.; Nelson, F.B.; Shaw, J.S.; Robins, S.C.; Daher, N.S.; Cohen, H.J.; Berk, L.S.; Bellinger, D.L.; Pargament, K.I.; et al. Religious vs. Conventional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Major Depression in Persons With Chronic Medical Illness: A Pilot Randomized Trial. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015, 203, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.; Li, K.K. Faith-Based Spiritual Intervention for Persons with Depression: Preliminary Evidence from a Pilot Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, M. Connectedness and connectedness: The dark side of spirituality–implications for education. Int. J. Child. Spiritual. 2012, 17, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, M.A.; Nagai-Jacobson, M.G. Spirituality: Living Our Connectedness; Nagai-Jacobson, M.G., Ed.; Delmar/Thomson Learning: Albany, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis, J.S. African American Women’s Definitions of Spirituality and Religiosity. J. Black Psychol. 2000, 26, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.B.; Stoll, R. Defining the Indefinable and Reviewing Its Place in Nursing. In Spiritual Dimension of Nursing Practice; Carson, V.B., Koenig, G.H., Eds.; Templeton Foundation Press: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, Z.W. Phenomenological Case Study of Spiritual Connectedness in the Academic Workplace. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnew, T.R. The Meaning Of Healing: Transcending Suffering. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.-S. Relation Between Lack of Forgiveness and Depression: The Moderating Effect of Self-Compassion. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 119, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangel, T.; Webb, J.R. Forgiveness and substance use problems among college students: Psychache, depressive symptoms, and hopelessness as mediators. J. Subst. Use 2018, 23, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos Algarra, C. The Role of Forgiveness in Disclosure and Victim Suport after a Patient Safety Incident. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr, J. Forgiveness: Overcoming versus Forswearing Blame. J. Appl. Philos. 2024, 41, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testerman, N. Forgiveness gives freedom. J. Christ. Nurs. Q. Publ. Nurses Christ. Fellowsh. 2014, 31, 214. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D.E.; Worthington, E.L., Jr.; Hook, J.N.; Hill, P.C. Research on religion/spirituality and forgiveness: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2013, 5, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, J.M.; Drescher, K.D.; Holland, J.M.; Lisman, R.; Foy, D.W. Spirituality, Forgiveness, and Quality of Life: Testing a Mediational Model with Military Veterans with PTSD. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2016, 26, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallen, D. Practicing forgiveness: A framework for a routine forgiveness practice. Spiritual. Clin. Pract. 2019, 6, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavell, M. Freedom and forgiveness. Int. J. Psychoanal. 2003, 84, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casellas-Grau, A.; Font, A.; Vives, J. Positive psychology interventions in breast cancer. A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritschel, L.A.; Sheppard, C.S. Hope and depression. In The Oxford Handbook of Hope; Gallagher, M.W., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxfored University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, H.; Ebrahimi, L.; Vatandoust, L. Effectiveness of hope therapy protocol on depression and hope in amphetamine users. Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, e21905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.-P. Spirituality, Connectedness, and Hope: The Higher Power Concept, Social Networks, and Inner Strengths. In Treating Addictions: The Four Components, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 209–244. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-C. Gratitude and depression in young adults: The mediating role of self-esteem and well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 87, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulbure, B.T. Appreciating the Positive Protects us from Negative Emotions: The Relationship between gratitude, Depression and Religiosity. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 187, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, M.; Bakhshi, A.; Khajuria, A.; Anand, P. Examining the association of Gratitude with psychological well-being of emerging adults: The mediating role of spirituality. Trends Psychol. 2022, 30, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.; Knepple Carney, A.; Hicks Patrick, J. Associations between gratitude and spirituality: An experience sampling approach. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2019, 11, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posternak, M.A.; Miller, I. Untreated short-term course of major depression: A meta-analysis of outcomes from studies using wait-list control groups. J. Affect. Disord. 2001, 66, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.; Altman, D.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Br. Med. J. 2010, 340, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; van Straten, A.; Bohlmeijer, E.; Hollon, S.; Andersson, G. The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: A meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. GPower 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portney, L.G. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Evidence-Based Practice; FA Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sudak, D.M.; Codd, R.T.; Ludgate, J.W.; Sokol, L.; Fox, M.G.; Reiser, R.; Milne, D.L. Teaching and Supervising Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Codd, R.T., Ludgate, J., Sokol, L., Fox, M.G., Reiser, R., Milne, D.L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, N.L.; Lyubomirsky, S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalom, I.D. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 5th ed.; Leszcz, M., Ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, N.; Bastida, E. Core religious beliefs and providing support to others in late life. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2009, 12, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellg, A.J.; Borrelli, B.; Resnick, B.; Hecht, J.; Minicucci, D.S.; Ory, M.; Ogedegbe, G.; Orwig, D.; Ernst, D.; Czajkowski, S. Enhancing Treatment Fidelity in Health Behavior Change Studies: Best Practices and Recommendations From the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenstein, S.M.; Fogg, L.; Garvey, C.; Hill, C.; Resnick, B.; Gross, D. Measuring Implementation Fidelity in a Community-Based Parenting Intervention. Nurs. Res. 2010, 59, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, L.G. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Overview and Results. Religions 2011, 2, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.-M.; Fong, T.; Tsui, E.; Au-Yeung, F.; Law, S. Validation of the Chinese Version of Underwood’s Daily Spiritual Experience Scale—Transcending Cultural Boundaries? Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 16, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, W.W.S.; Ng, I.S.W.; Wong, C.C.Y. Resilience: Enhancing Well-Being Through the Positive Cognitive Triad. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Sympson, S.C.; Ybasco, F.C.; Borders, T.F.; Babyak, M.A.; Higgins, R.L. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.C.H. Factor Structure of the Chinese Version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire among Hong Kong Chinese Caregivers. Health Soc. Work. 2014, 39, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaeinasab, H.; Saffari, M.; Sheykh-Oliya, Z.; Khalaji, K.; Laluie, A.; Al Zaben, F.; Koenig, H.G. A spiritual intervention to reduce stress, anxiety and depression in pregnant women: Randomized controlled trial. Health Care Women Int. 2021, 42, 1340–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, L.A.; Afiyanti, Y.; Kurniawati, W. The effectiveness of spiritual intervention in overcoming anxiety and depression problems in gynecological cancer patients. J. Keperawatan Indones. 2021, 24, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjadian, M.; Bahrami Ehsan, H.; Saboni, K.; Vahedi, S.; Rostami, R.; Roshani, D. A pilot randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of Islamic spiritual intervention and of breathing technique with heart rate variability feedback on anxiety, depression and psycho-physiologic coherence in patients after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 19, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Long, E.T. Suffering and Transcendence. Int. J. Philos. Relig. 2006, 60, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmarin, D.H.; Salcone, S.; Harper, D.; Forester, B.P. Spiritual psychotherapy for inpatient, residential, and intensive treatment. Am. J. Psychother. 2019, 72, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabifar, A.; Mosavi, A.; Jahromi, A.T.; Hosseini, N. Randomized Controlled Trial Study of the Impact of a Spiritual Intervention on Hope and Spiritual Well-Being of Persons with Cancer. Investig. Educ. Enfermería 2021, 39, e08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasution, L.A.; Afiyanti, Y.; Kurniawati, W. Effectiveness of spiritual intervention toward coping and spiritual well-being on patients with gynecological cancer. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 7, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, L.; Ganzevoort, R.R.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. Transcending the Suffering in Cancer: Impact of a Spiritual Life Review Intervention on Spiritual Re-Evaluation, Spiritual Growth and Psycho-Spiritual Wellbeing. Religions 2020, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, T.Y.; Çekiç, Y.; Altay, B. The effects of spiritual care intervention on spiritual well-being, loneliness, hope and life satisfaction of intensive care unit patients. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 77, 103438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.E.; Vaughn, J.M.; Yoo, Y.; Tirrell, J.M.; Dowling, E.M.; Lerner, R.M.; Geldhof, G.J.; Lerner, J.V.; Iraheta, G.; Williams, K.; et al. Exploring religiousness and hope: Examining the roles of spirituality and social connections among Salvadoran youth. Religions 2020, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Torrelles, M.; Monforte-Royo, C.; Rodríguez-Prat, A.; Porta-Sales, J.; Balaguer, A. Understanding meaning in life interventions in patients with advanced disease: A systematic review and realist synthesis. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, R.; Mousavizadeh, R.; Mohammadirizi, S.; Bahrami, M. The Effect of a spiritual care program on the self-esteem of patients with Cancer: A quasi-experimental study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2022, 27, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, S. The effect of spiritual intervention on self-esteem and emotional adjustment of mothers with children with cancer. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2023, 9, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gábová, K.; Maliňáková, K.; Tavel, P. Associations of self-esteem with different aspects of religiosity and spirituality. Ceskoslov. Psychol. 2021, 65, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheadle, A.C.D.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Untangling the mechanisms underlying the links between religiousness, spirituality, and better health. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, S.; Bierman, A.; Upenieks, L.; Ellison, C.G. Love thy self? How belief in a supportive God shapes self-esteem. Rev. Relig. Res. 2017, 59, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.I.; Crosby, R.G., III. Unpacking religious affiliation: Exploring associations between Christian children’s religious cultural context, God image, and self-esteem across development. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 35, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montes, K.S.; Tonigan, J.S. Does age moderate the effect of spirituality/religiousness in accounting for Alcoholics Anonymous benefit? Alcohol. Treat. Q. 2017, 35, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stearns, M.; Nadorff, D.K.; Lantz, E.D.; McKay, I.T. Religiosity and depressive symptoms in older adults compared to younger adults: Moderation by age. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 238, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.-H.; Ho, F.Y.-Y.; Shi, N.-K.; Tong, J.T.-Y.; Chung, K.-F.; Yeung, W.-F.; Ng, C.H.; Oliver, G.; Sarris, J. Smartphone-delivered multicomponent lifestyle medicine intervention for depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 89, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Stump, T.E.; Chen, C.X.; Kean, J.; Bair, M.J.; Damush, T.M.; Krebs, E.E.; Monahan, P.O. Minimally important differences and severity thresholds are estimated for the PROMIS depression scales from three randomized clinical trials. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, B.; Unutzer, J.; Callahan, C.M.; Perkins, A.J.; Kroenke, K. Monitoring Depression Treatment Outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med. Care 2004, 42, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Total (N = 57) | Intervention Group | WL Control Group | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N, %) | (n = 28) | (n = 29) | ||

| Gender | 0.49 | |||

| Male | 14 (24.6) | 8 (28.6) | 6 (20.7) | |

| Female | 43 (75.4) | 20 (71.4) | 23 (79.3) | |

| Age group (years) | 0.162 | |||

| 18–25 | 3 (5.3) | 1 (3.6) | 2 (6.9) | |

| 26–35 | 4 (7.0) | 4 (14.3) | 0 | |

| 36–45 | 9 (15.8) | 6 (21.4) | 3 (10.3) | |

| 46–55 | 21 (36.8) | 9 (32.1) | 12 (41.4) | |

| 56–64 | 20 (35.1) | 8 (28.6) | 12 (41.4) | |

| Religion | 0.367 | |||

| Protestant Christian | 49 (86.0) | 25 (89.3) | 24 (82.8) | |

| Roman Catholic | 2 (3.5) | 0 | 2 (6.9) | |

| Non-religious | 6 (10.5) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (10.3) | |

| Educational level | 0.227 | |||

| Primary | 2 (3.5) | 0 | 2 (6.9) | |

| Secondary | 19 (33.3) | 12 (42.9) | 7 (24.1) | |

| Undergraduate | 27 (47.4) | 13 (46.4) | 14 (48.3) | |

| Postgraduate | 9 (15.8) | 3 (10.7) | 6 (20.7) | |

| Marital status | 0.17 | |||

| Single | 22 (38.6) | 11 (39.3) | 11 (37.9) | |

| Married | 27 (47.4) | 14 (50.0) | 13 (44.8) | |

| Divorced | 4 (7.0) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Widowed | 4 (7.0) | 0 | 4 (13.8) | |

| Occupation | 0.504 | |||

| Full-time student | 5 (8.8) | 2 (7.1) | 3 (10.3) | |

| Full-time employee | 25 (43.9) | 14 (50.0) | 11 (37.9) | |

| Part-time employee | 8 (14.0) | 4 (14.3) | 4 (13.8) | |

| Unemployed | 6 (10.5) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (10.3) | |

| Retired | 9 (15.8) | 2 (7.1) | 7 (24.1) | |

| Others | 4 (7.0) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Treatment | 0.516 | |||

| Yes | 33 (57.9) | 15 (62.1) | 18 (57.9) | |

| No | 24 (42.1) | 13 (37.9) | 11 (42.1) |

| Variables | Total (N = 57) (Mean, SD) | Intervention Group (n = 28) (Mean, SD) | WL Control Group (n = 29) (Mean, SD) | t-Value | p-Value * | Mean Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSES | 56.51 (12.74) | 57.39 (12.44) | 55.66 (13.19) | 0.511 | 0.611 | 1.738 (−5.072–8.547) |

| SHS | 25.44 (8.74) | 27.82 (8.24) | 23.14 (8.72) | 2.083 | 0.042 * | 4.683 (0.177–9.190) |

| SHS-Agency | 11.37 (5.43) | 12.61 (5.05) | 10.17 (5.6) | 1.721 | 0.091 | 2.435 (−0.401–5.271) |

| SHS-Pathway | 14.07 (3.74) | 15.21 (3.55) | 12.97 (3.64) | 2.360 | 0.022 * | 2.249 (0.339–4.159) |

| MLQ | 44.21 (10.25) | 46.89 (10.24) | 41.62 (9.73) | 1.993 | 0.051 | 5.272 (−0.030–10.575) |

| MLQ-Presence | 19.44 (6.78) | 20.57 (6.64) | 18.35 (6.85) | 1.246 | 0.218 | 2.227 (−1.356–5.809) |

| MLQ-Search | 24.77 (6.44) | 26.32 (4.64) | 23.28 (7.59) | 1.821 | 0.073 | 3.046 (−0.293–6.384) |

| RSES | 24.88 (5.04) | 25.21 (5.06) | 24.55 (5.09) | 0.493 | 0.624 | 0.663 (−2.031–3.357) |

| MSPSS | 50.32 (13.97) | 51.82 (14.36) | 48.86 (13.67) | 0.797 | 0.429 | 2.959 (−4.483–10.402) |

| MSPSS-Family | 15.40 (5.45) | 16.64 (5.36) | 14.21 (5.36) | 1.716 | 0.092 | 2.436 (−0.409–5.281) |

| MSPSS-Friend | 17.09 (5.16) | 17.14 (5.67) | 17.03 (4.71) | 0.079 | 0.938 | 0.108 (−2.654–2.871) |

| MSPSS-Sig. others | 17.83 (5.36) | 18.04 (5.22) | 17.62 (5.57) | 0.290 | 0.773 | 0.415 (−2.452–3.282) |

| PHQ-9 | 9.51 (4.26) | 9.07 (4.62) | 9.93 (3.92) | −0.759 | 0.451 | −0.860 (−3.130–1.411) |

| GAD-7 | 8.56 (4.70) | 8.21 (4.90) | 8.90 (4.56) | −0.544 | 0.588 | −0.682 (−3.195–1.830) |

| Intervention vs. Waitlist Control | ||

|---|---|---|

| Measures | Mean Difference [95% CI] | Cohen’s d |

| Primary outcomes | ||

| Depression (PHQ-9) | −6.184 [−8.046, −4.322] | −1.801 *** |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | −4.858 [−6.500, −3.216] | −1.605 *** |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Spiritual experience (DSES) | 6.403 [2.454, 10.351] | 0.879 ** |

| Hope (SHS) | 8.720 [5.077, 12.363] | 1.298 *** |

| Agency thinking (SHS-Agency) | 5.341 [3.307, 7.375] | 1.424 *** |

| Pathway thinking (SHS-Pathway) | 3.386 [1.474, 5.298] | 0.960 ** |

| Meaning in life (MLQ) | 6.394 [0.234, 12.555] | 0.563 * |

| Presence of meaning in life (MLQ-Presence) | 3.863 [0.285, 7.442] | 0.585 * |

| Search of meaning in life (MLQ-Search) | 1.877 [−1.008, 4.761] | 0.353 |

| Self-esteem (RSES) | 1.777 [0.304, 3.249] | 0.654 * |

| Perceived social support (MSPSS) | 5.646 [−0.385, 11.678] | 0.508 |

| Perceived support from family (MSPSS-Family) | 2.223 [−0.337, 4.783] | 0.471 |

| Perceived support from friends (MSPSS-Friend) | 1.741 [−0.703, 4.186] | 0.386 |

| Perceived support from significant others (MSPSS-Sig.) | 1.555 [−0.447, 3.556] | 0.420 |

| Outcome Variables | Mean Difference (SE) | p-Value (Age * Group) | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | |||

| Depression (PHQ-9) | −4.746 (1.612) * | 0.004 | −1.221 (−0.349, −2.093) |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | −4.447 (1.647) | 0.077 | −1.120 (−0.254, −1.986) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Spiritual experience (DSES) | 8.213 (4.231) | 0.457 | 0.805 (−0.046, 1.656) |

| Hope (SHS) | 8.669 (2.920) * | 0.036 | 1.231 (0.359, 2.104) |

| Agency thinking (SHS-Agency) | 4.912 (1.705) * | 0.013 | 1.195 (0.324, 2.065) |

| Pathway thinking (SHS-Pathway) | 3.757 (1.463) | 0.193 | 1.065 (0.202, 1.928) |

| Meaning in life (MLQ) | 3.680 (4.642) | 0.293 | 0.329 (−0.508, 1.166) |

| Presence of meaning in life (MLQ-Presence) | 4.195 (3.081) | 0.164 | 0.565 (−0.278, 1.407) |

| Search for meaning in life (MLQ-Search) | −0.515 (2.438) | 0.816 | −0.088 (−0.922, 0.747) |

| Self-esteem (RSES) | 2.163 (1.557) | 0.086 | 0.576 (−0.267, 1.419) |

| Perceived social support (MSPSS) | 11.135 (4.386) * | 0.033 | 1.053 (0.191, 1.915) |

| Perceived support from family (MSPSS-Family) | 3.833 (1.832) | 0.060 | 0.868 (0.014, 1.721) |

| Perceived support from friends (MSPSS-Friend) | 4.085 (1.873) * | 0.046 | 0.904 (0.049, 1.760) |

| Perceived support from significant others (MSPSS-Sig.) | 3.217 (1.529) | 0.142 | 0.873 (0.019, 1.726) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leung, J.; Li, K.-K. Spiritual Connectivity Intervention for Individuals with Depressive Symptoms: A Randomized Control Trial. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161604

Leung J, Li K-K. Spiritual Connectivity Intervention for Individuals with Depressive Symptoms: A Randomized Control Trial. Healthcare. 2024; 12(16):1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161604

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeung, Judy, and Kin-Kit Li. 2024. "Spiritual Connectivity Intervention for Individuals with Depressive Symptoms: A Randomized Control Trial" Healthcare 12, no. 16: 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161604

APA StyleLeung, J., & Li, K.-K. (2024). Spiritual Connectivity Intervention for Individuals with Depressive Symptoms: A Randomized Control Trial. Healthcare, 12(16), 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161604