Estimation of the Global Disease Burden of Depression and Anxiety between 1990 and 2044: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Software

3. Results

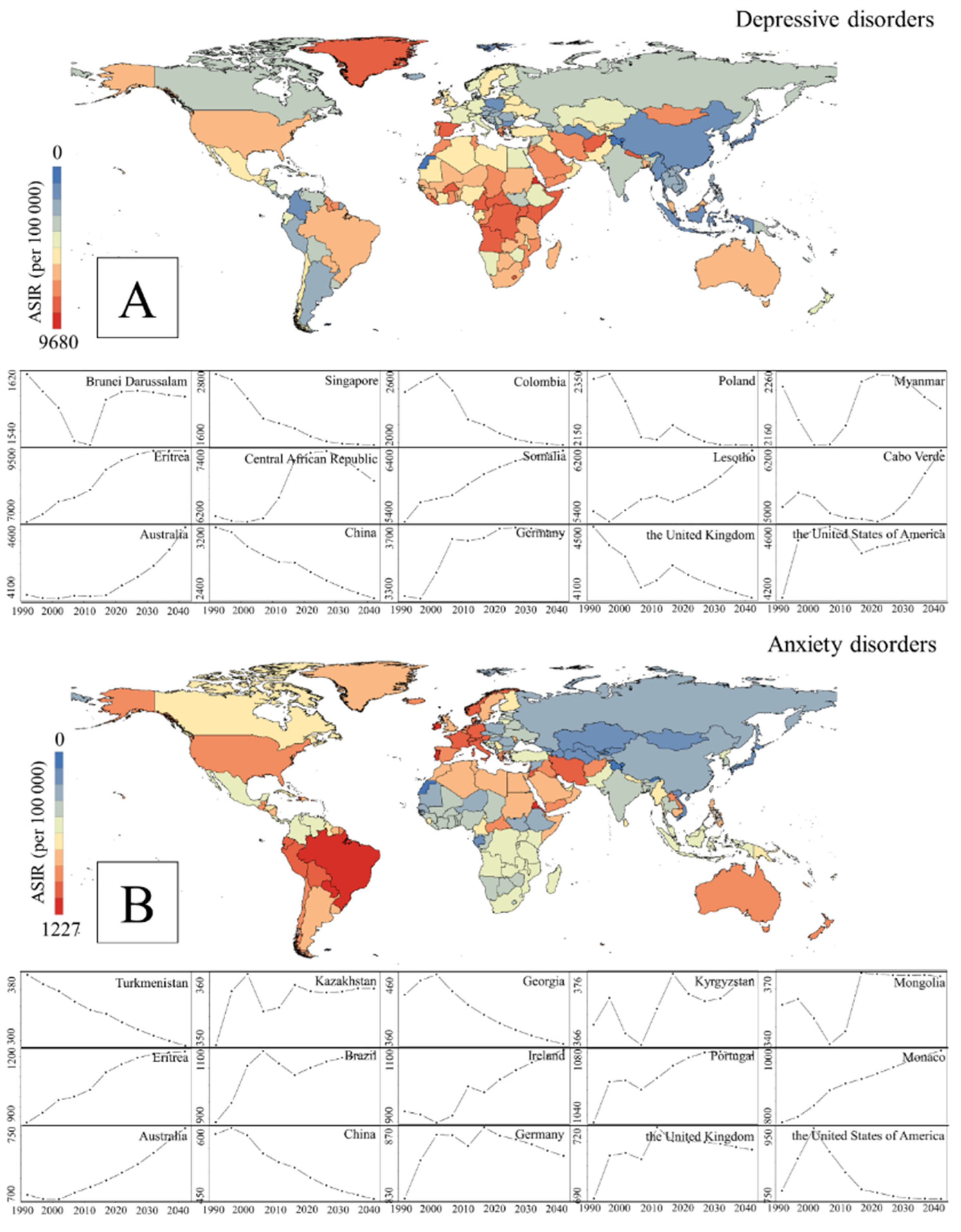

3.1. Burden and Time Trends for Depressive and Anxiety Disorders

3.2. Variation in the Burden of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in Sex and Age Groups

3.3. Burden of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in Different SDI Countries

3.4. Attributable Risk Factors of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders

3.5. Predication of Incidence Rate of Depression and Anxiety Disorders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DALYs | disability-adjusted life years |

| GHDx | Global Health Data Exchange |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SDI | socio-demographic index |

| ASIR | age-standardized incidence rate |

| ASPR | age-standardized prevalence rate |

| UIs | uncertainty intervals |

| APC | age–period–cohort |

References

- Yang, X.; Fang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Yin, X.; Man, J.; Yang, L.; Lu, M. Global, regional and national burden of anxiety disorders from 1990 to 2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, B.L.; Abramson, L.Y.; Moffitt, T.E.; Silva, P.A.; McGee, R.; Angell, K.E. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1998, 107, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger, J.C.; Davidson, J.R.; Lecrubier, Y.; Nutt, D.J.; Foa, E.B.; Kessler, R.C.; McFarlane, A.C.; Shalev, A.Y. Consensus statement on posttraumatic stress disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Ping, S.; Liu, X. Gender differences in depression, anxiety, and stress among college students: A longitudinal study from China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 263, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Does old age reduce the risk of anxiety and depression? A review of epidemiological studies across the adult life span. Psychol. Med. 2000, 30, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauldry, S. Variation in the protective effect of higher education against depression. Soc. Ment. Health 2015, 5, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, F.J.; Katon, W. Socioeconomic status, depression disparities, and financial strain: What lies behind the income-depression relationship? Health Econ. 2005, 14, 1197–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frerichs, R.R.; Aneshensel, C.S.; Yokopenic, P.A.; Clark, V.A. Physical health and depression: An epidemiologic survey. Prev. Med. 1982, 11, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.C.; Zuroff, D.C. Family structure and depression in female college students: Effects of parental conflict, decision-making power, and inconsistency of love. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1979, 88, 398. [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi, F.; Prokopenko, I.; Perry, J.D.; Kennedy, J.L.; McCarthy, A.D.; Holsboer, F.; Berrettini, W.; Middleton, L.T.; Chilcoat, H.D.; Muglia, P. Family history of depression is associated with younger age of onset in patients with recurrent depression. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, D.A.; Rehm, L.P. Family interaction patterns and childhood depression. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1986, 14, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gathergood, J. Debt and depression: Causal links and social norm effects. Econ. J. 2012, 122, 1094–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E. Associations between Socioeconomic Factors and Alcohol Outcomes. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, J.; Boyle, M.; Offord, D.R.; Racine, Y. Stress, social support and depression in single and married mothers. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003, 38, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, S.; Bierman, A.; Ellison, C.G. Religion and Mental Health. In Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.W. Depression and moral health: A response to the commentary. Philos. Psychiatry Psychol. 1999, 6, 295–298. [Google Scholar]

- Mjelde-Mossey, L.A.; Chi, I.; Lou, V.W.Q. Relationship between adherence to tradition and depression in Chinese elders in China. Aging Ment. Health 2006, 10, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinelli, M.; Wilkinson, G. Gender differences in depression: Critical review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.; Finkelhor, D. Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 99, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.L.; Longhurst, J.G.; Mazure, C.M. Childhood sexual abuse as a risk factor for depression in women: Psychosocial and neurobiological correlates. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.E.; Norman, R.E.; Suetani, S.; Thomas, H.J.; Sly, P.D.; Scott, J.G. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, W.M. The relationship among bullying, victimization, depression, anxiety, and aggression in elementary school children. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1998, 24, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.E.; Satyen, L. Cross-cultural differences in intimate partner violence and depression: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 24, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.R.; Pourdehghan, P.; Mostafavi, S.A.; Hooshyari, Z.; Ahmadi, N.; Khaleghi, A. Generalized anxiety disorder: Prevalence, predictors, and comorbidity in children and adolescents. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 73, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, E.A.; Bui, E.; Marques, L.; Metcalf, C.A.; Morris, L.K.; Robinaugh, D.J.; Worthington, J.J.; Pollack, M.H.; Simon, N.M. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: Effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, A.J.; Beck, A.T.; Kovacs, M.; Hollon, S. Comparative efficacy of cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressed outpatients. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1977, 1, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, K.J.; Mayberg, H.S. Targeting abnormal neural circuits in mood and anxiety disorders: From the laboratory to the clinic. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Smit, J.H.; Zitman, F.G.; Nolen, W.A.; Spinhoven, P.; Cuijpers, P.; De Jong, P.J.; Van Marwijk, H.W.J.; Assendelft, W.J.J. The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): Rationale, objectives and methods. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 17, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, V.; Van de Velde, S. Bracke, Professional care seeking for mental health problems among women and men in Europe: The role of socioeconomic, family-related and mental health status factors in explaining gender differences. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1641–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, O.P.; Draper, B.; Pirkis, J.; Snowdon, J.; Lautenschlager, N.T.; Byrne, G.; Sim, M.; Stocks, N.; Kerse, N.; Flicker, L.; et al. Anxiety, depression, and comorbid anxiety and depression: Risk factors and outcome over two years. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fan, R.; Lu, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Kong, G.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J. Prevalence of psychological symptoms and associated risk factors among nurses in 30 provinces during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2023, 30, 100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, C.; Newport, D.J.; Heit, S.; Graham, Y.P.; Wilcox, M.; Bonsall, R.; Miller, A.H.; Nemeroff, C.B. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA 2000, 284, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, E.; Li, Y.; Shao, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, W.; Shang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Gao, C.; et al. Childhood sexual abuse and the risk for recurrent major depression in Chinese women. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strohacker, E.; Wright, L.E.; Watts, S.J. Gender, Bullying Victimization, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidality. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2021, 65, 1123–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unützer, J.; Park, M. Strategies to improve the management of depression in primary care. Prim. Care 2012, 39, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenov, K.; Cabello, M.; Nieto, M.; Bernard, R.; Kohls, E.; Rummel-Kluge, C.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. Research Recommendations for Improving Measurement of Treatment Effectiveness in Depression. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, M.; Caspi, A.; Milne, B.J.; Danese, A.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E. Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Singh, S.S.; Calhoun, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, X.; Yang, F. Generalized anxiety disorder in urban China: Prevalence, awareness, and disease burden. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 234, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, E.; Rincon, C.J.; Martínez, N.T.; Rodriguez, N.; Tiemeier, H.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Gómez-Restrepo, C.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C. Housing index, urbanisation level and lifetime prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders: A cross-sectional analysis of the Colombian national mental health survey. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, P.R. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, P.; Liu, M.; Liu, B.; Hall, B. Trends in the incidence and DALYs of anxiety disorders at the global, regional, and national levels: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandanger, I.; Nygård, J.F.; Sørensen, T.; Moum, T. Is women’s mental health more susceptible than men’s to the influence of surrounding stress? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.H. Why women earn less: The theory and estimation of differential overqualification. Am. Econ. Rev. 1978, 68, 360–373. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C.; Breen, A.; Flisher, A.J.; Kakuma, R.; Corrigall, J.; Joska, J.A.; Swartz, L.; Patel, V. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sözeri-Varma, G. Depression in the elderly: Clinical features and risk factors. Aging Dis. 2012, 3, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bukh, J.; Bock, C.; Vinberg, M.; Gether, U.; Kessing, L. Differences Between Early and Late Onset Adult Depression. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2011, 7, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A.; Sharma, P.; Khandelwal, S.K. Late onset depression: A recent update. J. Ment. Health Hum. Behav. 2015, 20, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Comijs, H.C.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Heeren, T.J. Late-life depression: The differences between early- and late-onset illness in a community-based sample. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegeman, J.M.; Kok, R.M.; van der Mast, R.C.; Giltay, E.J. Phenomenology of depression in older compared with younger adults: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 200, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.G. Depression in late life: Review and commentary. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naismith, S.L.; Norrie, L.M.; Mowszowski, L.; Hickie, I.B. The neurobiology of depression in later-life: Clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging and pathophysiological features. Prog. Neurobiol. 2012, 98, 99–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, R.; Senra, C.; Fernández-Rey, J.; Merino, H. Sociotropy, Autonomy and Emotional Symptoms in Patients with Major Depression or Generalized Anxiety: The Mediating Role of Rumination and Immature Defenses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, M. Stress and depression in the employed population. Health Rep. 2006, 17, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sander, J.B.; McCarty, C.A. Youth depression in the family context: Familial risk factors and models of treatment. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 8, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Y.S.; Segel-Karpas, D. Aging anxiety, loneliness, and depressive symptoms among middle-aged adults: The moderating role of ageism. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 290, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.T.; Szenczy, A.K.; Klein, D.N.; Hajcak, G.; Nelson, B.D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021, 52, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, E.; Clark, D.M. Understanding Social Anxiety Disorder in Adolescents and Improving Treatment Outcomes: Applying the Cognitive Model of Clark and Wells (1995). Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 21, 388–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.M. The Mindful Path through Worry and Rumination: Letting Go of Anxious and Depressive Thoughts; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.G.; Kazdin, A.E.; Chiu, W.T.; Sampson, N.A.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Altwaijri, Y.; Andrade, L.H.; Cardoso, G.; et al. Findings From World Mental Health Surveys of the Perceived Helpfulness of Treatment for Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, S.; Disney, R. Debt and depression. J. Health Econ. 2010, 29, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, R.J.; Wang, J. Patterns of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and diet in US adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bort-Roig, J.; Briones-Buixassa, L.; Felez-Nobrega, M.; Guàrdia-Sancho, A.; Sitjà-Rabert, M.; Puig-Ribera, A. Sedentary behaviour associations with health outcomes in people with severe mental illness: A systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridley, M.; Rao, G.; Schilbach, F.; Patel, V. Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms. Science 2020, 370, eaay0214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Sampson, N.A.; Berglund, P.; Gruber, M.J.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Andrade, L.; Bunting, B.; Demyttenaere, K.; Florescu, S.; de Girolamo, G.; et al. Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2015, 24, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; He, H.; Yang, J.; Feng, X.; Zhao, F.; Lyu, J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 126, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M. Anxiety in education. In International Handbook of Emotions in Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, H.; Setoya, Y.; Suzuki, Y. Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in East and South East Asia. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddock, A.; Blair, C.; Ean, N.; Best, P. Psychological and social interventions for mental health issues and disorders in Southeast Asia: A systematic review. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, X.-M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. Mental Health-Related Stigma in China. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Aoki, Y.; Thornicroft, G. Review of mental-health-related stigma in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 67, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-I.; Jeon, M. The Stigma of Mental Illness in Korea. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2016, 55, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.-T.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, G.; Zeng, L.-N.; Ungvari, G.S. Prevalence of mental disorders in China. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 467–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, G.A.; Moeller, T.P.; Benett, J. Childhood sexual abuse and the consequences in adult women. Obstet. Gynecol. 1988, 71, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koverola, C.; Pound, J.; Heger, A.; Lytle, C. Relationship of child sexual abuse to depression. Child Abuse Negl. 1993, 17, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, F.W. Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniglio, R. Child sexual abuse in the etiology of depression: A systematic review of reviews. Depress. Anxiety 2010, 27, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chi, P.; Long, H.; Ren, X. Bullying victimization and depression among left-behind children in rural China: Roles of self-compassion and hope. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 96, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Gao, T.; Ren, H.; Hu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Liang, L.; Mei, S. The relationship between bullying victimization and depression in adolescents: Multiple mediating effects of internet addiction and sleep quality. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.M.; Neupane, D.; Rijal, S.; Thapa, K.; Mishra, S.R.; Poudyal, A.K. Sleep quality, internet addiction and depressive symptoms among undergraduate students in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.I.; Khanam, R.; Kabir, E. Bullying victimization, mental disorders, suicidality and self-harm among Australian high schoolchildren: Evidence from nationwide data. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Robinson, E.; Oginni, O.; Rahman, Q.; Rimes, K.A. Anxiety disorders, gender nonconformity, bullying and self-esteem in sexual minority adolescents: Prospective birth cohort study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, K.; Mak, J.; Bacchus, L.; Child, J.; Falder, G.; Petzold, M.; Astbury, J.; Watts, C. Intimate Partner Violence and Incident Depressive Symptoms and Suicide Attempts: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | ASIR | ASPR | Age-Standardized DALY Rate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | Upper | Lower | Change | Rate | Upper | Lower | Change | Rate | Upper | Lower | Change | |

| Global | 3588.25 | 4060.42 | 3152.71 | −5.79 | 3440.05 | 3817.64 | 3097.01 | −4.22 | 577.75 | 788.88 | 405.79 | −4.97 |

| High SDI | 4013.63 | 4550.43 | 3545.48 | 0.99 | 3581.47 | 3985.85 | 3230.01 | 0.50 | 626.84 | 852.48 | 438.47 | 1.03 |

| High–middle SDI | 3184.21 | 3583.66 | 2809.60 | −11.16 | 3151.21 | 3472.33 | 2851.66 | −9.04 | 523.01 | 713.05 | 367.02 | −10.84 |

| Middle SDI | 3139.00 | 3540.43 | 2765.35 | −4.79 | 3194.79 | 3534.33 | 2873.67 | −3.36 | 521.68 | 709.93 | 366.80 | −4.03 |

| Low–middle SDI | 4180.30 | 4740.48 | 3660.97 | −11.82 | 3839.57 | 4261.99 | 3440.78 | −7.83 | 654.34 | 897.85 | 458.32 | −9.71 |

| Low SDI | 4770.22 | 5461.66 | 4142.24 | −9.79 | 4283.03 | 4818.15 | 3805.88 | −6.83 | 738.87 | 1011.24 | 514.68 | −7.90 |

| Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia | 3176.93 | 3618.38 | 2772.56 | 9.69 | 3081.42 | 3442.33 | 2747.08 | 7.15 | 513.51 | 701.96 | 359.29 | 8.95 |

| Central Asia | 3327.42 | 3825.36 | 2888.66 | −3.57 | 3186.51 | 3644.09 | 2807.90 | −2.93 | 534.90 | 741.82 | 372.57 | −2.64 |

| Central Europe | 2436.80 | 2771.69 | 2132.45 | −12.87 | 2601.01 | 2956.18 | 2309.75 | −8.87 | 413.89 | 572.31 | 290.54 | −11.19 |

| Eastern Europe | 3546.80 | 4062.82 | 3076.08 | −9.93 | 3316.40 | 3683.91 | 2964.16 | −7.11 | 562.24 | 771.76 | 391.45 | −7.99 |

| High-income | 4179.27 | 4712.02 | 3699.39 | −6.11 | 3659.91 | 4062.62 | 3307.44 | −4.74 | 647.16 | 882.46 | 451.97 | −4.97 |

| Australasia | 5079.18 | 5925.80 | 4368.05 | −2.53 | 4284.28 | 4908.87 | 3764.64 | −1.32 | 777.82 | 1094.07 | 538.62 | −1.84 |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 2320.99 | 2600.80 | 2063.54 | 10.04 | 2084.27 | 2313.10 | 1885.57 | 5.49 | 365.65 | 499.26 | 253.57 | 7.78 |

| High-income North America | 4885.16 | 5532.44 | 4308.48 | 8.77 | 4270.27 | 4743.29 | 3867.94 | 4.43 | 753.77 | 1023.69 | 525.53 | 6.67 |

| Southern Latin America | 3313.55 | 3745.45 | 2925.62 | 4.72 | 2777.33 | 3111.55 | 2492.50 | 1.68 | 503.29 | 690.90 | 349.65 | 3.73 |

| Western Europe | 4347.46 | 4912.74 | 3841.95 | 28.37 | 3851.28 | 4296.63 | 3448.09 | 13.92 | 677.20 | 929.50 | 475.01 | 20.69 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 3983.79 | 4483.33 | 3524.74 | −8.56 | 3417.06 | 3791.43 | 3079.39 | −5.40 | 607.23 | 824.73 | 423.12 | −6.72 |

| Andean Latin America | 2886.58 | 3315.19 | 2499.39 | −2.63 | 2725.64 | 3105.16 | 2379.98 | −1.97 | 462.07 | 640.03 | 318.12 | −1.96 |

| Caribbean | 4336.17 | 5007.13 | 3737.42 | −5.36 | 3673.61 | 4178.74 | 3212.46 | −3.71 | 657.19 | 905.93 | 454.07 | −4.01 |

| Central Latin America | 3675.78 | 4181.96 | 3219.65 | −7.47 | 3198.45 | 3562.30 | 2865.73 | −4.93 | 563.62 | 771.17 | 392.72 | −6.00 |

| Tropical Latin America | 4560.16 | 5058.00 | 4084.43 | −0.63 | 3799.36 | 4168.93 | 3464.31 | −0.94 | 686.08 | 932.46 | 482.44 | −1.00 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 5098.60 | 5947.72 | 4378.86 | 0.59 | 4348.89 | 4971.11 | 3807.29 | 0.46 | 781.06 | 1075.62 | 535.18 | 0.52 |

| South Asia | 4179.15 | 4727.18 | 3668.72 | −3.51 | 3794.72 | 4199.68 | 3416.01 | −2.10 | 645.08 | 877.70 | 452.66 | −3.01 |

| Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania | 2274.02 | 2548.25 | 2016.08 | −10.20 | 2723.91 | 3022.42 | 2451.50 | −6.96 | 415.06 | 569.35 | 290.21 | −8.39 |

| East Asia | 2292.26 | 2562.45 | 2043.67 | −4.25 | 2720.13 | 3004.92 | 2449.91 | −2.36 | 415.98 | 573.46 | 291.93 | −2.85 |

| Oceania | 2711.59 | 3193.17 | 2306.26 | −9.64 | 3044.75 | 3541.71 | 2622.94 | −6.45 | 476.09 | 663.22 | 325.58 | −8.23 |

| Southeast Asia | 2060.52 | 2341.00 | 1797.73 | −9.19 | 2610.58 | 2958.36 | 2302.92 | −9.16 | 389.23 | 536.55 | 270.38 | −9.20 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 5072.06 | 5771.53 | 4432.41 | 1.06 | 4540.40 | 5112.41 | 4038.07 | 0.71 | 786.51 | 1083.35 | 549.28 | 0.13 |

| Central Sub-Saharan Africa | 6646.94 | 7819.84 | 5680.50 | −4.74 | 5536.91 | 6307.63 | 4801.31 | −3.47 | 1000.16 | 1397.69 | 682.15 | −3.81 |

| Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa | 5466.48 | 6234.48 | 4781.02 | −6.43 | 4849.21 | 5416.77 | 4317.19 | −4.90 | 845.40 | 1154.93 | 589.89 | −5.09 |

| Southern Sub-Saharan Africa | 4552.32 | 5105.97 | 4015.91 | −4.17 | 4166.26 | 4612.26 | 3736.31 | −3.10 | 705.61 | 958.57 | 497.87 | −3.56 |

| Western Sub-Saharan Africa | 4407.30 | 5021.82 | 3851.35 | −6.04 | 4075.39 | 4556.07 | 3633.02 | −4.06 | 693.84 | 949.29 | 485.18 | −4.80 |

| Region | ASIR | ASPR | Age-Standardized DALY Rate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | Upper | Lower | Change | Rate | Upper | Lower | Change | Rate | Upper | Lower | Change | |

| Global | 585.45 | 709.53 | 474.21 | 1.04 | 3779.52 | 4473.26 | 3181.07 | 1.74 | 360.12 | 494.44 | 248.60 | 2.13 |

| High SDI | 710.54 | 872.80 | 570.38 | 3.37 | 4806.55 | 5782.42 | 4017.17 | 1.10 | 456.89 | 626.95 | 312.75 | 1.18 |

| High–middle SDI | 584.85 | 704.58 | 476.96 | 2.07 | 3754.47 | 4406.91 | 3188.73 | 2.83 | 359.98 | 494.80 | 250.24 | 2.66 |

| Middle SDI | 599.21 | 719.35 | 487.91 | −0.94 | 3793.62 | 4438.95 | 3220.87 | −1.37 | 363.15 | 497.93 | 252.87 | −1.34 |

| Low–middle SDI | 549.87 | 670.04 | 446.34 | −0.30 | 3470.02 | 4097.03 | 2909.21 | −0.52 | 328.89 | 451.62 | 228.88 | −0.16 |

| Low SDI | 556.08 | 686.33 | 444.56 | −2.87 | 3494.81 | 4240.76 | 2879.71 | −3.24 | 331.48 | 455.65 | 226.98 | −2.88 |

| Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia | 470.73 | 576.51 | 379.52 | 10.05 | 2993.33 | 3562.52 | 2501.28 | 11.64 | 285.83 | 392.62 | 197.74 | 11.98 |

| Central Asia | 371.71 | 464.99 | 290.94 | −0.05 | 2221.55 | 2773.54 | 1751.53 | −0.04 | 212.77 | 298.07 | 142.78 | 0.78 |

| Central Europe | 506.31 | 624.14 | 403.70 | −5.91 | 3276.15 | 3986.55 | 2685.65 | −9.55 | 313.31 | 435.32 | 212.34 | −9.10 |

| Eastern Europe | 504.11 | 605.85 | 408.39 | −0.53 | 3188.52 | 3719.63 | 2727.09 | −0.89 | 304.66 | 414.36 | 214.57 | −0.39 |

| High-income | 735.38 | 896.97 | 593.37 | 0.72 | 5058.29 | 6047.44 | 4242.70 | 0.59 | 480.87 | 657.48 | 330.35 | 1.29 |

| Australasia | 848.68 | 1077.15 | 661.32 | 1.06 | 6031.85 | 7447.53 | 4885.40 | −0.32 | 575.65 | 805.72 | 383.79 | −0.12 |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 433.60 | 528.98 | 351.23 | 4.57 | 2616.41 | 3108.17 | 2184.38 | 3.65 | 253.02 | 350.79 | 174.36 | 3.56 |

| High-income North America | 806.33 | 987.22 | 643.52 | 3.98 | 5559.91 | 6582.64 | 4693.53 | 3.63 | 521.52 | 709.05 | 362.54 | 3.53 |

| Southern Latin America | 730.02 | 871.88 | 604.80 | −6.76 | 5125.85 | 5885.12 | 4459.77 | −6.91 | 491.15 | 662.28 | 343.49 | −6.59 |

| Western Europe | 791.24 | 977.02 | 629.18 | 8.12 | 5626.62 | 6814.10 | 4632.75 | 7.71 | 537.89 | 748.20 | 364.59 | 7.41 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 780.33 | 957.51 | 621.61 | 0.61 | 5502.31 | 6588.71 | 4625.85 | −0.92 | 524.13 | 721.08 | 361.15 | −0.58 |

| Andean Latin America | 787.71 | 1006.92 | 610.28 | 10.11 | 5497.27 | 6893.06 | 4467.76 | 16.07 | 527.34 | 741.83 | 351.37 | 16.46 |

| Caribbean | 669.28 | 846.20 | 520.30 | 2.59 | 4400.69 | 5499.82 | 3522.48 | 2.72 | 419.78 | 587.13 | 279.15 | 3.39 |

| Central Latin America | 609.11 | 757.86 | 484.47 | 2.14 | 3930.74 | 4782.64 | 3253.45 | 2.51 | 376.21 | 521.35 | 258.09 | 2.95 |

| Tropical Latin America | 989.45 | 1208.28 | 791.17 | 2.68 | 7378.64 | 8605.85 | 6296.08 | 1.81 | 700.17 | 953.94 | 487.24 | 2.01 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 783.08 | 980.97 | 615.84 | 4.12 | 5135.71 | 6267.23 | 4164.90 | 3.74 | 492.15 | 685.31 | 333.99 | 3.81 |

| South Asia | 497.90 | 596.56 | 403.59 | 2.43 | 3045.53 | 3547.16 | 2594.45 | 2.55 | 286.44 | 390.78 | 200.71 | 2.42 |

| Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania | 539.27 | 644.14 | 442.13 | 1.15 | 3292.85 | 3821.73 | 2801.90 | 0.74 | 317.21 | 434.13 | 222.90 | 1.29 |

| East Asia | 525.02 | 620.38 | 434.05 | 4.37 | 3180.75 | 3663.70 | 2712.31 | 4.70 | 307.61 | 421.59 | 215.22 | 5.21 |

| Oceania | 626.04 | 786.47 | 488.65 | −2.43 | 4006.76 | 4990.40 | 3182.94 | −5.56 | 380.21 | 531.82 | 253.59 | −5.18 |

| Southeast Asia | 578.70 | 710.45 | 464.32 | 1.76 | 3633.25 | 4314.97 | 3024.10 | −0.48 | 347.56 | 475.99 | 242.08 | −0.48 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 547.81 | 680.19 | 436.12 | −0.19 | 3462.63 | 4184.23 | 2839.15 | 0.45 | 329.74 | 457.57 | 224.61 | −0.09 |

| Central Sub-Saharan Africa | 604.33 | 768.91 | 465.78 | 0.62 | 3863.99 | 4826.48 | 3089.56 | 0.79 | 366.32 | 516.87 | 244.62 | 1.26 |

| Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa | 575.22 | 719.92 | 453.32 | 14.85 | 3716.29 | 4530.63 | 3050.00 | 25.06 | 353.88 | 487.70 | 241.11 | 25.67 |

| Southern Sub-Saharan Africa | 576.08 | 701.31 | 461.61 | 0.08 | 3657.96 | 4307.84 | 3100.42 | 1.50 | 345.37 | 472.97 | 241.16 | 1.53 |

| Western Sub-Saharan Africa | 499.15 | 612.78 | 401.76 | 1.31 | 3066.50 | 3683.28 | 2532.61 | 1.58 | 293.35 | 405.93 | 201.14 | 2.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Ning, W.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, B.; Mao, Y. Estimation of the Global Disease Burden of Depression and Anxiety between 1990 and 2044: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171721

Liu J, Ning W, Zhang N, Zhu B, Mao Y. Estimation of the Global Disease Burden of Depression and Anxiety between 1990 and 2044: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Healthcare. 2024; 12(17):1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171721

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jinnan, Wei Ning, Ning Zhang, Bin Zhu, and Ying Mao. 2024. "Estimation of the Global Disease Burden of Depression and Anxiety between 1990 and 2044: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019" Healthcare 12, no. 17: 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171721

APA StyleLiu, J., Ning, W., Zhang, N., Zhu, B., & Mao, Y. (2024). Estimation of the Global Disease Burden of Depression and Anxiety between 1990 and 2044: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Healthcare, 12(17), 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171721