Preparedness of Nursing Homes: A Typology and Analysis of Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis in a French Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources, Instruments, and Collection

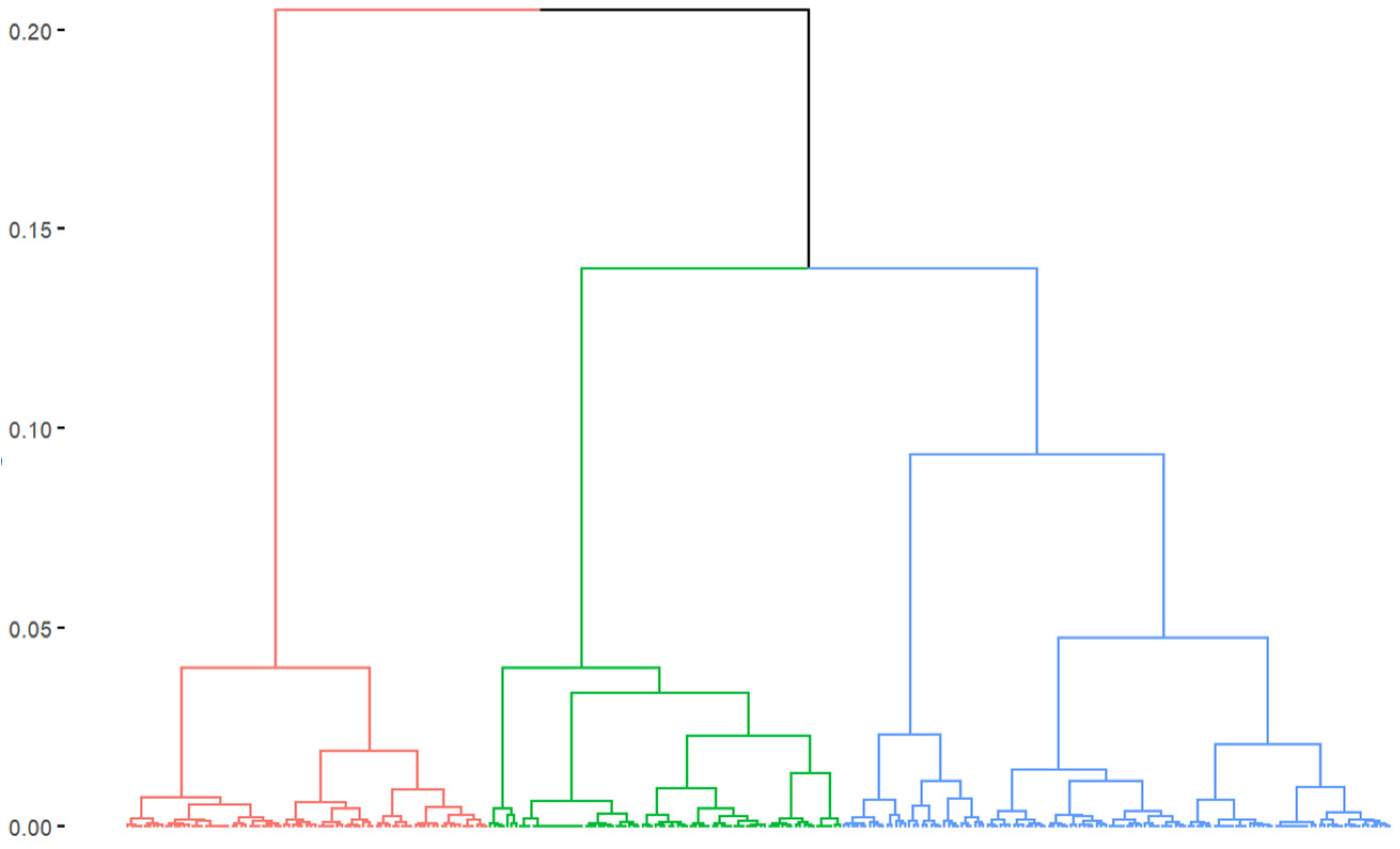

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. A Network with Diverse Characteristics

3.2. Three Profiles of NHs within the Network

- Cluster 1: This cluster comprises 86 NHs (29.7%) (Table 3). These are large facilities (>100 beds in 30.2% of cases), where residents are generally more dependent than in the other network’s NHs (average GMP of 743.5). The NHs in this cluster are mostly located in urban areas with hospital emergency services, but with a low level of primary care territorial structuring. These NHs are in areas with a low number of available NH beds and a low institutionalization rate in NHs.

- Cluster 2: This cluster comprises 100 NHs (34.5%). These are smaller facilities: 44.0% of them report having fewer than 80 beds. These NHs are more frequently located in rural areas than the other network’s NHs. They are in areas with a lower presence of hospital emergency services and a low level of primary care territorial structuring. In the territories where these NHs are located, the number of NH beds is within the average observed across the network, as is the proportion of institutionalized seniors over 75 years old. The magnitude of the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak was higher in the territories of NHs in Clusters 1 and 2 than in the rest of the network.

- Cluster 3: This cluster comprises 104 NHs (35.9%). These are medium-sized facilities, hosting less dependent residents compared to the other network’s NHs (average GMP of 722.1). The majority of NHs in this cluster are located in areas with hospital emergency services and a high level of primary care territorial structuring. These NHs are mainly in urban areas, where the proportion of seniors over 75 years old in the population is high, as is the proportion of seniors institutionalized in NHs. The number of NH beds in these areas is higher than in the rest of the network. The magnitude of the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak was lower in the territories of the NHs in this third cluster than in other network territories.

3.3. Outcomes of the Outbreak: Mortality and Hospitalization Requests

3.4. Prevention and Control Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asfoor, D.A.; Tabche, C.; Al-Zadjali, M.; Mataria, A.; Saikat, S.; Rawaf, S. Concept analysis of health system resilience. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2024, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, J.D.; MacNeill, A.J.; Biddinger, P.D.; Ergun, O.; Salas, R.N.; Eckelman, M.J. Sustainable and Resilient Health Care in the Face of a Changing Climate. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2023, 44, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, S.G.; Lorenzoni, V.; Pirri, S.; Turchetti, G. What are the Characteristics of a Resilient Healthcare System: A Scoping Review. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2475348/v1 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Peterson, L.J. Protecting nursing home residents in disasters: The urgent need for a new approach amid mounting climate warnings. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 702–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cefalu, C.A. Disaster Preparedness for Seniors: A Comprehensive Guide for Healthcare Professionals; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4939-0665-9 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- National Research Council (U.S.). Health Care Comes Home: The Human Factors; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; 189p.

- Usher, K.; Durkin, J.; Gyamfi, N.; Warsini, S.; Jackson, D. Preparedness for viral respiratory infection pandemic in residential aged care facilities: A review of the literature to inform post-COVID-19 response. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. A Strategic Framework for Emergency Preparedness. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/a-strategic-framework-for-emergency-preparedness (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Khan, Y.; O’Sullivan, T.; Brown, A.; Tracey, S.; Gibson, J.; Généreux, M.; Henry, B.; Shwartz, B. Public health emergency preparedness: A framework to promote resilience. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/pandemic-influenza-preparedness-framework (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Lane, S.J.; McGrady, E. Measures of emergency preparedness contributing to nursing home resilience. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2018, 61, 751–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Interim Guidance for Influenza Outbreak Management in Long-Term Care and Post-Acute Care Facilities|CDC. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/ltc-facility-guidance.htm (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- NHS. Influenza Guidance for Care Homes. 2019. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/london/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/12/Appx-7-NHSI-Infection-Control-Team-Influenza-Guidance-for-Care-Homes.docx (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Holstein, J.; Canouï-Poitrine, F.; Neumann, A.; Lepage, E.; Spira, A. Were less disabled patients the most affected by 2003 heat wave in nursing homes in Paris, France? J. Public Health 2005, 27, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGS FM of H. Le Plan de Gestion des Tensions Hospitalières et des Situations Sanitaires Exceptionnelles des Établissements de Santé. Ministère du Travail, de la Santé et des Solidarités, 2024. Available online: https://sante.gouv.fr/prevention-en-sante/securite-sanitaire/guide-gestion-tensions-hospitalieres-SSE (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Fouillet, A.; Pontais, I.; Caserio-Schönemann, C. Excess all-cause mortality during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in France, March to May 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2001485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canouï-Poitrine, F.; Rachas, A.; Thomas, M.; Carcaillon-Bentata, L.; Fontaine, R.; Gavazzi, G.; Laurent, M.; Robine, J.-M. Magnitude, change over time, demographic characteristics and geographic distribution of excess deaths among nursing home residents during the first wave of COVID-19 in France: A nationwide cohort study. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbalayen, F.; Mir, S.; de l’Estoile, V.; Letty, A.; Le Bruchec, S.; Pondjikli, M.; Seringe, E.; Berrut, G.; Kabirian, F.; Fourrier, M.-A.; et al. Impact of the first COVID-19 epidemic wave in a large French network of nursing homes: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmin, J.; Um-Din, N.; Donadio, C.; Magri, M.; Nghiem, Q.D.; Oquendo, B.; Pariel, S.; Lafuente-Lafuente, C. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outcomes in French Nursing Homes That Implemented Staff Confinement with Residents. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020, 3, e2017533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.J.; Coste, J.; Canouï-Poitrine, F.; Pouchot, J.; Rachas, A.; Carcaillon-Bentata, L. Impact of the First COVID-19 Pandemic Wave on Hospitalizations and Deaths Caused by Geriatric Syndromes in France: A Nationwide Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisado-Clavero, M.; Ares-Blanco, S.; Serafini, A.; Del Rio, L.R.; Larrondo, I.G.; Fitzgerald, L.; Vinker, S.; van Pottebergh, G.; Valtonen, K.; Vaes, B.; et al. The role of primary health care in long-term care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic in 30 European countries: A retrospective descriptive study (Eurodata study). Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2023, 24, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantur, D.; İşeri-Say, A. Organizational resilience: A conceptual integrative framework. J. Manag. Organ. 2012, 18, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Majumdar, S.; et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet. Res. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, S.; Josseran, L. How primary healthcare sector is organized at the territorial level in France? A typology of territorial structuring. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2024, 13, 8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, S.; Ray, M.; Rousseau, A.; Seixas, C.; Baumann, S.; Gaucher, L.; LeBreton, J.; Bouchez, T.; Saint-Lary, O.; Ramond-Roquin, A.; et al. Primary healthcare and COVID-19 in France: Contributions of a research network including practitioners and researchers. Sante Publique 2022, 33, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monziols, M. Comment les médecins généralistes ont-ils exercé leur activité pendant le confinement lié au COVID-19? Etudes Résultats 2020, 1150, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lenti, C. Évaluation de la Nouvelle «Hotline Gériatrique» du CHU de Grenoble Auprès des Médecins Généralistes et Médecins Coordinateurs en EHPAD: Connaissance, Utilisation, Satisfaction Perçue. 2021. Available online: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-03349789v1/file/2021GRAL5106_lenti_camille_dif.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Basile, G.; Agodi, A. Applying a hierarchical clustering on principal components approach to identify different patterns of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic across Italian regions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, F.; Josse, J.; Pagès, J. Principal Component Methods—Hierarchical Clustering—Partitional Clustering: Why Would We Need to Choose for Visualizing Data? Appl. Math. Dep. 2010, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, M.; Riedel, M.; Mot, E.; Willemé, P.; Röhrling, G.; Czypionka, T. A Typology of Long-Term Care Systems in Europe. ENEPRI Research Report No. 91. August 2010. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Typology-of-Long-Term-Care-Systems-in-Europe.-No.-Kraus-Riedel/a478c1885dbba3dc2f26e8cdddd4a23936899766 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Fischer, J.; Frisina Doetter, L.; Rothgang, H. Comparing long-term care systems: A multi-dimensional, actor-centred typology. Soc. Policy Adm. 2022, 56, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, J.M.; Ströbel, A.M.; Holle, B.; Palm, R. Empirical development of a typology on residential long-term care units in Germany—Results of an exploratory multivariate data analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, N.S.; Zimmerman, S.; Sloane, P.D.; Gruber-Baldini, A.L.; Eckert, J.K. An empirical typology of residential care/assisted living based on a four-state study. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestage, C.; Dubuc, N.; Bravo, G. Développement et validation d’une classification québécoise des résidences privées avec services accueillant des personnes âgées. Can. J. Aging 2014, 33, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujmovic, M.; Roederer, T.; Frison, S.; Melki, C.; Lauvin, T.; Grellety, E. COVID-19 in French nursing homes during the second pandemic wave: A mixed-methods cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, A.W.; Renton, M.; Wehbi, N.K.; Sheehan, E.J.; Gregorio, T.M.; Yurkofsky, M.; Levine, S.; Jackson, V.; Pu, C.T.; Lipsitz, L.A. Building community and resilience in Massachusetts nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2716–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühl, A.; Hering, C.; Herrmann, W.J.; Gangnus, A.; Kohl, R.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Kuhlmey, A.; Gelert, P. General practitioner care in nursing homes during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: A retrospective survey among nursing home managers. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, P.; Mas Bergas, M.A.; Puig, J.; Isnard, M.; Massot, M.; Vedia, C.; Peiró, R.; Ordorica, Y.; Pablo, S.; Ulldemolins, M.; et al. COVIDApp as an Innovative Strategy for the Management and Follow-Up of COVID-19 Cases in Long-Term Care Facilities in Catalonia: Implementation Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e21163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debie, A.; Nigusie, A.; Gedle, D.; Khatri, R.B.; Assefa, Y. Building a resilient health system for universal health coverage and health security: A systematic review. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2024, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Events/Decisions | H8 Indicator Levels from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker [23] |

|---|---|---|

| Before | (None.) | 0—No measures. |

| March 5 | (None.) | 1—Recommended isolation, hygiene, and visitor restriction measures in LTCFs and/or elderly people required to stay at home. |

| March 6 | Activation of the plan bleu in nursing homes (national decision). | (Same as above: level 1.) |

| March 11 | Stopping of visits in nursing homes extended to the entirety of France. | 3—Extensive restrictions for isolation and hygiene in LTCFs, all non-essential external visitors prohibited, and/or all elderly people required to stay at home and not leave the home with minimal exceptions, and receive no external visitors. |

| March 12 | Blue plan extended to all elderly care facilities (including facilities for people with disabilities). | (Same as above: level 3.) |

| March 17 | Widespread lockdown in France. | (Same as above: level 3.) |

| April 1 | Inclusion of deaths in nursing homes in the total count of COVID-19-related deaths. | (Same as above: level 3.) |

| April 1 | Opinion of the national ethics advisory committee on measures concerning nursing homes and the role of professional teams (director, coordinating physician) in the implementation of lockdown. | (Same as above: level 3.) |

| April 6 | Announcement of the initiation of screening in facilities hosting the most vulnerable individuals and professionals, primarily in nursing homes. | (Same as above: level 3.) |

| April 20 | Reintroduction of supervised visitation rights for the elderly in nursing homes with strict adherence to barrier measures. | (Same as above: level 3.) |

| May 12 | (None.) | 2—Narrow restrictions for isolation, hygiene in LTCFs, some limitations on external visitors and/or restrictions protecting elderly people at home. |

| n (%) | N = 290 |

|---|---|

| French administrative region | |

| Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 30 (10.3) |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 10 (3.4) |

| Bretagne | 3 (1.0) |

| Centre-Val-de-Loire | 22 (7.6) |

| Grand-Est | 21 (7.2) |

| Hauts-de-France | 14 (4.8) |

| Ile-de-France | 63 (21.7) |

| Normandie | 16 (5.5) |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 36 (12.4) |

| Occitanie | 23 (7.9) |

| Pays-de-la-Loire | 13 (4.5) |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur | 39 (13.4) |

| Number of accommodation beds * | |

| <80 beds | 109 (37.6) |

| 80–100 beds | 123 (42.4) |

| >100 beds | 58 (20.0) |

| Mean age of residents (years old) | 88.3 |

| Presence of a protected living unit † | 201 (69.3) |

| Presence of a PASA ‡ | 38 (13.1) |

| Percentage of residents who fall § | |

| <40% | 15 (5.2) |

| 40–50% | 38 (13.1) |

| ≥50% | 237 (81.2) |

| Presence of a hospital emergency service in the municipality | 158 (54.5) |

| Primary care territorial structuring (municipality level) ** | |

| Under- or unstructured | 68 (23.4) |

| With potential for structuring | 103 (35.5) |

| In the way for structuring | 112 (38.6) |

| Already structured | 7 (2.4) |

| Number of accommodation places per 1000 people aged 75 and over in the county †† | |

| <100 | 74 (25.5) |

| 100–130 | 150 (51.7) |

| ≥130 | 66 (22.8) |

| Percentage of the people aged 75 and over in the county living in a nursing home | |

| <9.5% | 198 (68.3) |

| ≥9.5% | 92 (31.7) |

| Percentage of people aged 75 and over in the total population of the county | |

| <8% | 73 (25.2) |

| 8–10% | 100 (34.5) |

| ≥10% | 117 (40.3) |

| Magnitude of the outbreak in the county ‡‡ | |

| Low | 178 (61.4) |

| Moderate | 67 (23.1) |

| High | 45 (15.5) |

| Questionnaire response rate | 192 (66.2) |

| n (%) | All N = 290 | Cluster 1 n = 86 (29.7) | Cluster 2 n = 100 (34.5) | Cluster 3 n = 104 (35.9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active variables | ||||

| Number of accommodation beds * | ||||

| <80 beds | 109 (37.6) | 24 (27.9) | 44 (44.0) | 41 (39.4) |

| 80–100 beds | 123 (42.4) | 36 (41.9) | 36 (36.0) | 51 (49.0) |

| >100 beds | 58 (20.0) | 26 (30.2) | 20 (20.0) | 12 (11.5) |

| Presence of a protected living unit † | 201 (69.3) | 57 (66.3) | 68 (68.0) | 76 (73.1) |

| Presence of a hospital emergency service in the municipality | 158 (54.5) | 47 (54.7) | 24 (24.0) | 87 (83.7) |

| Primary care territorial structuring (municipality level) ‡ | ||||

| Under- or unstructured | 68 (23.4) | 26 (30.2) | 37 (37.0) | 5 (4.8) |

| With potential for structuring | 103 (35.5) | 40 (46.5) | 48 (48.0) | 15 (14.4) |

| In the way for structuring | 112 (38.6) | 20 (23.3) | 14 (14.0) | 78 (75.0) |

| Already structured | 7 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (5.8) |

| Number of accommodation places per 1000 people aged 75 and over in the county § | ||||

| <100 | 74 (25.5) | 61 (70.9) | 5 (5.0) | 8 (7.7) |

| 100–130 | 150 (51.7) | 25 (29.1) | 85 (85.0) | 40 (38.5) |

| ≥130 | 66 (22.8) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (10.0) | 56 (53.8) |

| Percentage of people aged 75 and over in the county living in a nursing home | ||||

| <9.5% | 198 (68.3) | 86 (100) | 79 (79.0) | 33 (31.7) |

| ≥9.5% | 92 (31.7) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (21.0) | 71 (68.3) |

| Percentage of people aged 75 and over in the total population of the county | ||||

| <8% | 73 (25.2) | 23 (26.7) | 41 (41.0) | 9 (8.7) |

| 8–10% | 100 (34.5) | 33 (38.4) | 38 (38.0) | 29 (27.9) |

| ≥10% | 117 (40.3) | 30 (34.9) | 21 (21.0) | 66 (63.5) |

| Urban or rural character of the county | ||||

| Rural | 23 (7.9) | 2 (2.3) | 19 (19.0) | 2 (1.9) |

| Urban | 267 (92.1) | 84 (97.7) | 81 (81.0) | 102 (98.1) |

| Illustrative variables | ||||

| Mean age of residents (years old) | 88.3 | 88.3 | 88.2 | 88.4 |

| Mean GMP ** | 732.9 | 743.5 | 735.1 | 722.1 |

| Percentage of wandering residents | ||||

| <20% | 71 (37.0) | 29 (49.2) | 20 (32.8) | 22 (30.6) |

| 20–30% | 69 (35.9) | 18 (30.5) | 21 (34.4) | 30 (41.7) |

| ≥30% | 52 (27.1) | 12 (20.3) | 20 (32.8) | 20 (27.8) |

| N.A. | 98 | 27 | 39 | 32 |

| Magnitude of the outbreak in the county †† | ||||

| Low | 178 (61.4) | 51 (59.3) | 52 (52.0) | 75 (72.1) |

| Medium | 67 (23.1) | 19 (22.1) | 25 (25.0) | 23 (22.1) |

| High | 45 (15.5) | 16 (18.6) | 23 (23.0) | 6 (5.8) |

| Questionnaire response rate | 192 (66.2) | 59 (68.6) | 61 (61.0) | 72 (69.2) |

| n (%) | All N = 192 | Cluster 1 n = 59 | Cluster 2 n = 61 | Cluster 3 n = 72 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 mortality | <0.05 | ||||

| At least 1 death | 81 (42.2) | 28 (47.5) | 31 (50.8) | 22 (30.6) | |

| No deaths | 111 (57.8) | 31 (52.5) | 30 (49.2) | 50 (69.4) | |

| Satisfying hospitalization requests for COVID-19 | <0.05 | ||||

| No requests | 99 (51.5) | 27 (45.8) | 30 (49.2) | 42 (58.3) | |

| Requests generally satisfied | 76 (39.6) | 31 (52.5) | 23 (37.7) | 22 (30.6) | |

| Requests generally unsatisfied | 17 (8.9) | 1 (1.7) | 8 (13.1) | 8 (11.1) |

| n (%) | All N = 192 | Cluster 1 n = 59 | Cluster 2 n = 61 | Cluster 3 n = 72 | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stopping of visits | N.S. | ||||

| Before March 11 | 132 (70.6) | 38 (66.7) | 43 (72.9) | 51 (71.8) | |

| March 11 or later | 55 (29.4) | 19 (33.3) | 16 (27.1) | 20 (28.2) | |

| Missing data | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Room confinement | N.S. | ||||

| Before March 11 | 49 (26.8) | 12 (21.4) | 13 (22.8) | 24 (34.3) | |

| March 11 or later | 134 (73.2) | 44 (78.6) | 44 (77.2) | 46 (65.7) | |

| Missing data | 9 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Cohorting | N.S. | ||||

| Yes | 177 (92.2) | 54 (91.5) | 57 (93.4) | 66 (91.7) | |

| No | 15 (7.8) | 5 (8.5) | 4 (6.6) | 6 (8.3) | |

| Dedicated COVID-19 units | N.S. | ||||

| No COVID-19 unit † | 73 (41.0) | 17 (30.9) | 24 (42.1) | 32 (48.5) | |

| Daytime-only dedicated staff | 22 (12.4) | 6 (10.9) | 5 (8.8) | 11 (16.7) | |

| Nighttime-only dedicated staff | 83 (46.6) | 32 (58.2) | 28 (49.1) | 23 (34.8) | |

| Missing data | 14 | 4 | 4 | 6 | |

| Audit of practices | <0.05 | ||||

| Yes | 141 (73.4) | 51 (86.4) | 44 (72.1) | 46 (63.9) | |

| No | 51 (26.6) | 8 (13.6) | 17 (27.9) | 26 (36.1) | |

| Support by an external hygiene team | N.S. | ||||

| Yes, in 2020 | 63 (32.8) | 25 (42.4) | 18 (29.5) | 20 (27.8) | |

| Yes, but prior to 2020 or without a visit | 60 (31.3) | 17 (28.8) | 19 (31.1) | 24 (33.3) | |

| No | 69 (35.9) | 17 (28.8) | 24 (39.3) | 28 (38.9) | |

| Resident mass testing | <0.01 | ||||

| April 6 or before | 14 (8.0) | 10 (18.2) | 4 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| After April 6 | 161 (92.0) | 45 (81.8) | 53 (93.0) | 63 (100) | |

| Missing data ‡ | 17 | 4 | 4 | 9 | |

| Staff mass testing | <0.001 | ||||

| April 6 or before | 11 (6.2) | 9 (16.7) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.5) | |

| After April 6 | 167 (93.8) | 45 (83.3) | 57 (98.3) | 65 (98.5) | |

| Missing data ‡ | 14 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gautier, S.; Mbalayen, F.; Dutheillet de Lamothe, V.; Ndiongue, B.M.; Pondjikli, M.; Berrut, G.; Clôt-Faybesse, P.; Jurado, N.; Fourrier, M.-A.; Armaingaud, D.; et al. Preparedness of Nursing Homes: A Typology and Analysis of Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis in a French Network. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171727

Gautier S, Mbalayen F, Dutheillet de Lamothe V, Ndiongue BM, Pondjikli M, Berrut G, Clôt-Faybesse P, Jurado N, Fourrier M-A, Armaingaud D, et al. Preparedness of Nursing Homes: A Typology and Analysis of Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis in a French Network. Healthcare. 2024; 12(17):1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171727

Chicago/Turabian StyleGautier, Sylvain, Fabrice Mbalayen, Valentine Dutheillet de Lamothe, Biné Mariam Ndiongue, Manon Pondjikli, Gilles Berrut, Priscilla Clôt-Faybesse, Nicolas Jurado, Marie-Anne Fourrier, Didier Armaingaud, and et al. 2024. "Preparedness of Nursing Homes: A Typology and Analysis of Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis in a French Network" Healthcare 12, no. 17: 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171727

APA StyleGautier, S., Mbalayen, F., Dutheillet de Lamothe, V., Ndiongue, B. M., Pondjikli, M., Berrut, G., Clôt-Faybesse, P., Jurado, N., Fourrier, M.-A., Armaingaud, D., Delarocque-Astagneau, E., & Josseran, L. (2024). Preparedness of Nursing Homes: A Typology and Analysis of Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis in a French Network. Healthcare, 12(17), 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171727