Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights and Service Use among Undocumented Migrants in the EU: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Sources and Search Terms

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Data Items

2.5. Assessment of Quality of Studies

2.6. Data Synthesis and Reporting

3. Results

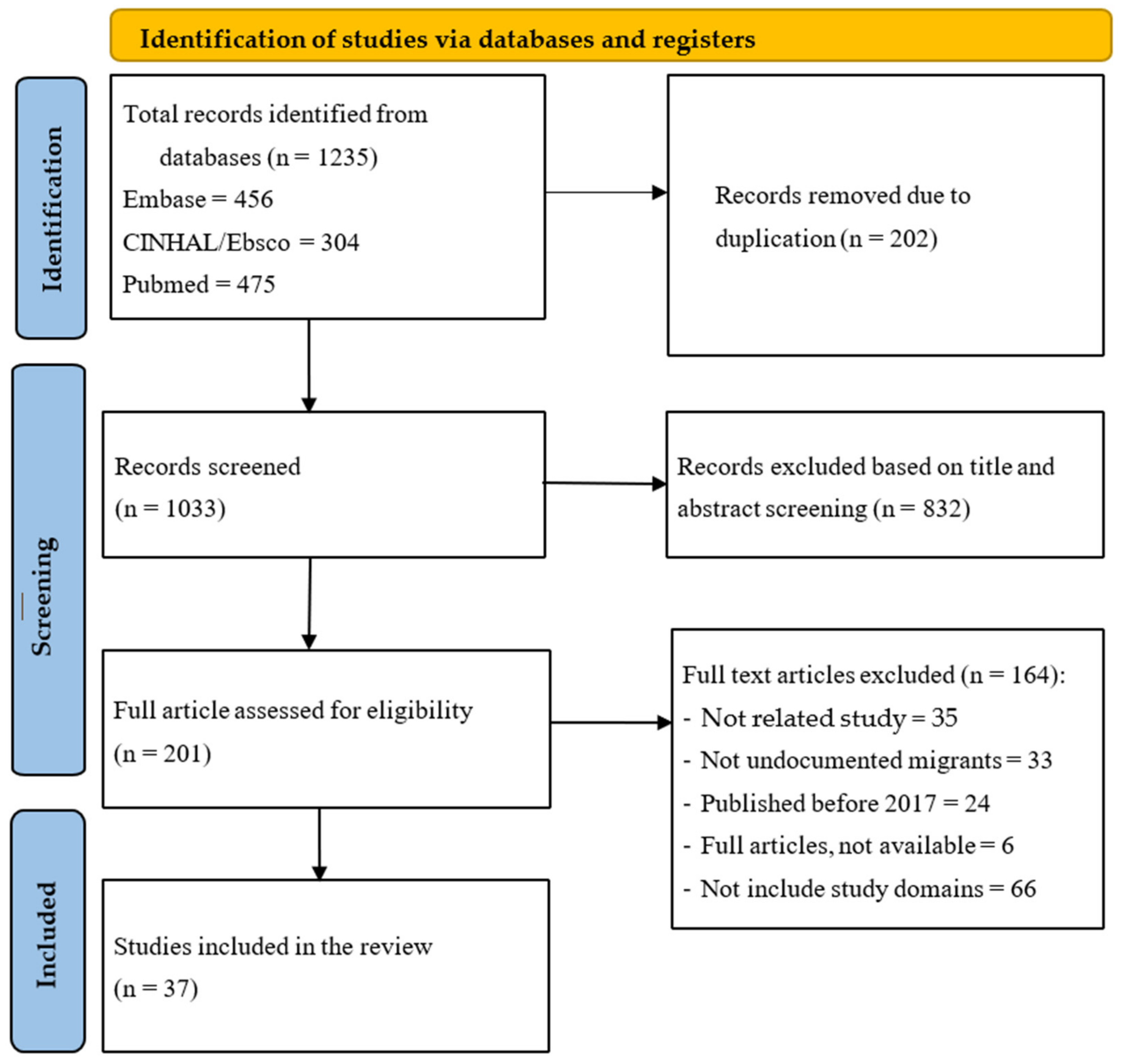

3.1. Search Results

3.2. General Description of the Selected Articles

3.3. Summary of Findings Related to Access to SRHSs for Undocumented Migrants

3.3.1. Availability

3.3.2. Approachability and Acceptability

3.3.3. Affordability

3.3.4. Appropriateness

3.3.5. SRHS Use and Health, Migration, and Economic Outcomes for Undocumented Migrants

3.3.6. Result of Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

Limitation of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA]. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: An Essential Element of Universal Health Coverage. Background Document for the Nairobi Summit on ICPD25—Accelerating the Promise; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population Development, 20th anniversary ed.; United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA]: New York, NY, USA, 2014.

- State of World Population—Unfinished Business; United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA]: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Plan for Sexual and Reproductive Health: Towards Achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Europe—Leaving No One Behind; World Health Organization (WHO) Office for Europe Action: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016.

- Smith, A.; Levoy, M. Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights of Undocumented Migrants, European Union. 2016. Available online: https://picum.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Sexual-and-Reproductive-Health-Rights_EN.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Achieving a World Free from Violence Against Women Domestic Violence (Istanbul Convention): What Is the Istanbul Convention? PICUM: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Picum Position Paper Undocumented Migrants and the Europe 2020 Strategy: Making Social Inclusion a Reality for All Migrants in Europe; PICUM: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Troutman, M.; Rafique, S.; Plowden, T.C. Are higher unintended pregnancy rates among minorities a result of disparate access to contraception? Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2020, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekerin, O.; Shomuyiwa, D.O.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., III; Agboola, O.O.; Damilola, A.S.; Onoja, S.O.; Chikwendu, C.F.; Manirambona, E. Restrictive migration policies and their impact on HIV prevention, care and treatment services. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2024, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savas, S.T.; Knipper, M.; Duclos, D.; Sharma, E.; Ugarte-Gurrutxaga, M.I.; Blanchet, K. Migrant-sensitive healthcare in Europe: Advancing health equity through accessibility, acceptability, quality, and trust. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 41, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union The 27 Member Countries of the EU. Available online: https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/countries_en#the-27-member-countries-of-the-eu (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- EFTA. Available online: https://www.efta.int/about-efta/the-efta-states (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Cuadra, C.B. Right of access to health care for undocumented migrants in EU: A comparative study of national policies. Eur. J. Public. Health 2012, 22, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, P.; Passel, J.S. Europe’s Unauthorized Immigrant Population Peaks in 2016, Then Levels Off; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Euronews. Here Are the Key Numbers about Migration to the EU You Need to Know. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/03/14/here-are-the-key-numbers-about-migration-to-the-eu-you-need-to-know (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Winters, M.; Rechel, B.; de Jong, L.; Pavlova, M. A systematic review on the use of healthcare services by undocumented migrants in Europe. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, L.; Pavlova, M.; Winters, M.; Rechel, B. A systematic literature review on the use and outcomes of maternal and child healthcare services by undocumented migrants in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, J.F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualizing access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme). Qualitative Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- NHLBI Quality Assessment Tools. 2022. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Tasa, J.; Holmberg, V.; Sainio, S.; Kankkunen, P.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. Maternal health care utilization and the obstetric outcomes of undocumented women in Finland—A retrospective register-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudtzen, F.C.; Mørk, L.; Nielsen, V.N.; Astrup, B.S. Accessing vulnerable undocumented migrants through a healthcare clinic including a community outreach programme: A 12-year retrospective cohort study in Denmark. J. Travel. Med. 2021, 29, taab128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R. NHS charging for maternity care in England: Its impact on migrant women. Crit. Soc. Policy 2021, 41, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogishvili, M.; Costa, S.A.; Flórez, K.; Huang, T.T. Policy implementation analysis on access to healthcare among undocumented immigrants in seven autonomous communities of Spain, 2012–2018. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funge, J.K.; Boye, M.C.; Parellada, C.B.; Norredam, M. Demographic characteristics, medical needs and utilisation of antenatal care among pregnant undocumented migrants living in Denmark between 2011 and 2017. Scand J. Public Health 2021, 50, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönborn, C.; De Spiegelaere, M.; Racape, J. Measuring the invisible: Perinatal health outcomes of unregistered women giving birth in Belgium, a population-based study. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, iii326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellums, L.B.; Powis, J.; Jones, L.; Miller, A.; Rustage, K.; Russell, N.; Friedland, J.S.; Hargreaves, S. “It’s a life you’re playing with”: A qualitative study on experiences of NHS maternity services among undocumented migrant women in England. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 270, 113610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, S.; van Dulm, E.; Boyd, A.; Generaal, E.; Eskander, S.; Joore, I.K.; van Cleef, B.; Siedenburg, E.; Bruisten, S.; van Duijnhoven, Y.; et al. Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infections among undocumented migrants and uninsured legal residents in the Netherlands: A cross-sectional study, 2018–2019. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.L.; Finnerty, F.; Richardson, D. Healthcare charging for migrants in the UK: Awareness and experience of clinicians within sexual and reproductive health and HIV. J. Public Health 2021, 43, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslier, M.; Deneux-Tharaux, C.; Sauvegrain, P.; Schmitz, T.; Luton, D.; Mandelbrot, L.; Estellat, C.; Azria, E. Association between Migrant Women’s Legal Status and Prenatal Care Utilization in the PreCARE Cohort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funge, J.K.; Boye, M.C.; Johnsen, H.; Nørredam, M. “No Papers. No Doctor”: A Qualitative Study of Access to Maternity Care Services for Undocumented Immigrant Women in Denmark. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.d.M.; López-Domene, E.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Faqyr, K.E.M.E.; Dobarrio-Sanz, I.; Granero-Molina, J. Understanding Violence against Women Irregular Migrants Who Arrive in Spain in Small Boats. Healthcare 2020, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, C.; Barlow, P.; Rozenberg, S. Urgent Medical Aid and Associated Obstetric Mortality in Belgium. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 22, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, G.; Castagno, R.; Rizzolo, R.; Armaroli, P.; Caprioglio, A.; Larato, C.; Giordano, L. A comparison of diagnostic indicators of cervical cancer screening among women accessing through volunteer organizations and those via the organized programme in Turin (Piedmont Region, Northern Italy). Epidemiol. Prev. 2020, 44, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Prats-Uribe, A.; Brugueras, S.; Comet, D.; Álamo-Junquera, D.; Ortega Gutiérrez Ll Orcau, À.; Caylà, J.A.; Millet, J.-P. Evidences supporting the inclusion of immigrants in the universal healthcare coverage. Eur. J Public Health 2020, 30, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wall-Wieler, E.; Urquia, M.; Carmichael, S.L.; Stephansson, O. Severe maternal morbidity among migrants with insecure residency status in Sweden 2000–2014: A population-based cohort study. J. Migr. Health 2020, 1–2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Cailhol, J. Are migration routes disease transmission routes? Understanding Hepatitis and HIV transmission amongst undocumented Pakistani migrants and asylum seekers in a Parisian suburb. Anthropol. Med. 2020, 27, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, S.J.; Crosby, L.J.; Turnbull, E.R.; Burns, R.; Miller, A.; Jones, L.; Aldridge, R.W. The negative health effects of hostile environment policies on migrants: A cross-sectional service evaluation of humanitarian healthcare provision in the UK. Wellcome Open Res. 2019, 4, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, C.; Heintze, C.; Holzinger, F. ‘Managing scarcity’—A qualitative study on volunteer-based healthcare for chronically ill, uninsured migrants in Berlin, Germany. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, J.; Quack Lötscher, K.C.; Eperon, I.; Gonik, L.; Martinez de Tejada, B.; Epiney, M.; Schmidt, N.C. Giving birth in Switzerland: A qualitative study exploring migrant women’s experiences during pregnancy and childbirth in Geneva and Zurich using focus groups. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Domene, E.; Granero-Molina, J.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; López-Rodríguez, M.d.M.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Guerra-Martín, M.D.; Jiménez-Lasserrrotte, M.d.M. Emergency Care for Women Irregular Migrants Who Arrive in Spain by Small Boat: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignier, N.; Desgrees Du Lou, A.; Pannetier, J.; Ravalihasy, A.; Gosselin, A.; Lert, F.; Lydie, N.; Bouchaud, O.; Spira, R.D.; Chauvin, P. Social and structural factors and engagement in HIV care of sub-Saharan African migrants diagnosed with HIV in the Paris region. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieles, N.C.; Tankink, J.B.; van Midde, M.; Düker, J.; van der Lans, P.; Wessels, C.M.; Bloemenkamp, K.W.M.; Bonsel, G.; van den Akker, T.; Goosen, S. Maternal and perinatal outcomes of asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Europe: A systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarenza, A.; Dauvrin, M.; Chiesa, V.; Baatout, S.; Verrept, H. Supporting access to healthcare for refugees and migrants in European countries under particular migratory pressure. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ahlberg, M.; Hjern, A.; Stephansson, O. Perinatal health of refugee and asylum-seeking women in Sweden 2014–17: A register-based cohort study. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignier, N.; Dray Spira, R.; Pannetier, J.; Ravalihasy, A.; Gosselin, A.; Lert, F.; Lydie, N.; Bouchaud, O.; Desgrees, A.; Lou, D. Refusal to provide healthcare to sub-Saharan migrants in France: A comparison according to their HIV and HBV status. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, C. Medical Care, Screening and Regularization of Sub-Saharan Irregular Migrants Affected by Hepatitis B in France and Italy. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkensjö, M.; Greenbrook JT v Rosenlundh, J.; Ascher, H.; Elden, H. The need for trust and safety inducing encounters: A qualitative exploration of women’s experiences of seeking perinatal care when living as undocumented migrants in Sweden. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-Gallego, L.; Gené-Badia, J.; Gallo, P. Effects of undocumented immigrants exclusion from health care coverage in Spain. Health Policy 2018, 122, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsanti, S. Hospitalization among migrants in Italy: Access to health care as an opportunity for integration and inclusion. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhrvold, T.; Småstuen, M.C. The mental healthcare needs of undocumented migrants: An exploratory analysis of psychological distress and living conditions among undocumented migrants in Norway. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.; Gama, A.; Pingarilho, M.; Simões, D.; Mendão, L. Health Services Use and HIV Prevalence Among Migrant and National Female Sex Workers in Portugal: Are We Providing the Services Needed? AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 2316–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea-Sánchez, M.; Gastaldo, D.; Molina-Luque, F.; Otero-García, L. Access and utilization of social and health services as a social determinant of health: The case of undocumented Latin American immigrant women working in Lleida (Catalonia, Spain). Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridolfo, A.L.; Oreni, L.; Vassalini, P.; Resnati, C.; Bozzi, G.; Milazzo, L.; Antinori, S.; Rusconi, S.; Galli, M. Effect of Legal Status on the Early Treatment Outcomes of Migrants Beginning Combined Antiretroviral Therapy at an Outpatient Clinic in Milan, Italy. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2017, 75, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, N.; Alessio, L.; Gualdieri, L.; Pisaturo, M.; Sagnelli, C.; Minichini, C.; Di Caprio, G.; Starace, M.; Onorato, L.; Signoriello, G.; et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in undocumented immigrants and refugees in Southern Italy: Demographic, virological, and clinical features. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2017, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, H. Paternity for Sale: Anxieties over “Demographic Theft” and Undocumented Migrant Reproduction in Germany. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2008, 22, 340–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebo, P.; Jackson, Y.; Haller, D.M.; Gaspoz, J.M.; Wolff, H. Sexual and Reproductive Health Behaviors of Undocumented Migrants in Geneva: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic of the Publication | Number of Publications (%) | Publication Reference Number (See Reference List) |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | ||

| 2020–2024 | 17 (46) | [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] |

| 2017–2019 | 20 (54) | [16,17,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] |

| Origin of the study | ||

| Southern Europe (PIGS- Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain) | 11 (30) | [25,33,35,36,42,50,51,53,54,55,56] |

| Northern, Central and East European countries | 15 (41) | [22,23,26,27,29,31,32,34,37,38,40,43,46,47,49] |

| EFTA countries (Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland) and UK | 6 (16) | [24,28,30,39,41,52] |

| Cross-country and multi-country studies (EU member states/Europe) (comparative analysis of two countries) | 5 (14) | [16,17,44,45,48] |

| Study objective | ||

| To assess and describe barriers to access, utilization and further needs for SRHSs for undocumented migrants | 11 (30) | [16,17,22,23,26,32,33,39,42,52,54] |

| Assessing the incidence/prevalence of STDs amongst the undocumented populations in the EU. More focused on single incidence of a disease within the population group (HIV, HBV, HCV…) | 3 (8) | [29,38,56] |

| Describe health outcomes related to (poor/inadequate) SRHS provision and use by undocumented migrants | 10 (27) | [17,22,24,27,31,34,37,43,44,46] |

| Investigate patients and provider experiences with SRHS provision and utilization | 7 (19) | [28,30,32,40,41,42,49] |

| To explore the gaps between national legislation/availability and utilization by undocumented migrants. The gap between “de juris” and “de facto” rights and entitlements to SRHSs. | 3 (8) | [25,47,50] |

| To compare differences in access, utilization, and outcomes across national, documented, and undocumented migrant populations | 7 (19) | [24,34,35,36,51,53,55] |

| Inform national/EU level policy to improve access to appropriate health services for undocumented migrant populations | 2 (5) | [45,48] |

| Research setting | ||

| Healthcare organization | 13 (35) | [30,31,35,36,38,40,41,43,45,47,48,55,56] |

| NGOs and volunteer-based health organizations | 11 (28) | [23,24,26,28,29,32,33,35,39,42,53] |

| Regions/cities/urban/rural areas (cities/autonomous communities) | 7 (19) | [22,25,49,50,51,52,54] |

| Registries and online databases (nation- wide, hospital, birth, pregnancy) | 7 (19) | [16,17,27,34,37,44,46] |

| Data Collection Characteristics | Number of Publications (%) | Publication Reference Number (See Reference List) |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | ||

| Qualitative (interviews, open-ended questionnaires, focus groups, consultation, case study, policy review, ethnographic research) | 15 (41) | [24,25,28,30,32,33,38,40,41,42,48,49,50,51,54] |

| Quantitative (cross-sectional, cohort studies) | 17 (46) | [22,23,26,27,29,31,34,35,36,37,39,43,46,47,53,55,56] |

| Literature review, systematic literature review | 3 (8) | [16,17,44] |

| Mixed-method approach | 2 (5) | [45,52] |

| Study population | ||

| Healthcare consumers/users/undocumented migrants | 31 (84) | [16,17,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,46,47,48,49,51,52,53,54,55,56] |

| Healthcare providers | 3 (8) | [30,40,45] |

| Key informants | 2 (5) | [42,45] |

| Review of published and unpublished literature. | 3 (8) | [25,44,50] |

| Sample size | ||

| 0–50 respondents | 11 (30) | [24,28,32,33,38,40,41,42,48,49,54] |

| 50–100 | 2 (5) | [22,52] |

| More than 100 | 19 (51) | [23,26,27,29,30,31,34,35,36,37,39,43,45,46,47,51,53,55,56] |

| Review of existing literature | 5 (14) | [16,17,25,44,50] |

| Method of data collection | ||

| Interview | 10 (27) | [24,28,32,33,40,41,42,48,49,54] |

| Questionnaire, survey | 4 (11) | [30,47,53,56] |

| Patients’ records, administrative files, official guidelines, hospital and patient registries | 11 (30) | [23,26,27,34,35,36,37,39,46,51,55] |

| Existing dataset (e.g., national surveys, published studies) | 2 (5) | [31,43] |

| Literature review | 5 (14) | [16,17,25,44,50] |

| Mixed (FDGs, interviews, questionnaires, and/or literature review, two or more of the above) | 6 (16) | [22,29,38,41,45,52] |

| Method of data analysis | ||

| Qualitative techniques (e.g., framework analysis) | 18 (49) | [16,17,24,25,28,30,32,33,38,40,41,42,44,45,48,49,50,54] |

| Quantitative techniques (statistical analysis) | 18 (49) | [22,23,26,27,29,31,34,35,36,37,39,43,46,47,51,53,55,56] |

| Mixed approach (qualitative and quantitative) | 1 (3) | [52] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mandroiu, A.; Alsubahi, N.; Groot, W.; Pavlova, M. Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights and Service Use among Undocumented Migrants in the EU: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171771

Mandroiu A, Alsubahi N, Groot W, Pavlova M. Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights and Service Use among Undocumented Migrants in the EU: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(17):1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171771

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandroiu, Alexandra, Nizar Alsubahi, Wim Groot, and Milena Pavlova. 2024. "Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights and Service Use among Undocumented Migrants in the EU: A Systematic Literature Review" Healthcare 12, no. 17: 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171771

APA StyleMandroiu, A., Alsubahi, N., Groot, W., & Pavlova, M. (2024). Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights and Service Use among Undocumented Migrants in the EU: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare, 12(17), 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171771