Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity (VUCA) in Healthcare

Abstract

1. Introduction

The VUCA Concept—Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity of the Surrounding World

- Volatility—the production costs of basic goods have continuously fluctuated, leading to financial fluctuations in terms of tariffs for goods and services provided;

- Uncertainty—there have been insights into understanding how events were triggered, but there is no certainty as to when and in what context they might recur;

- Complexity—there has been an uncontrollable accumulation of variables that have complicated the normal and known way of doing things (costs, tariffs, legislation, people, etc.);

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

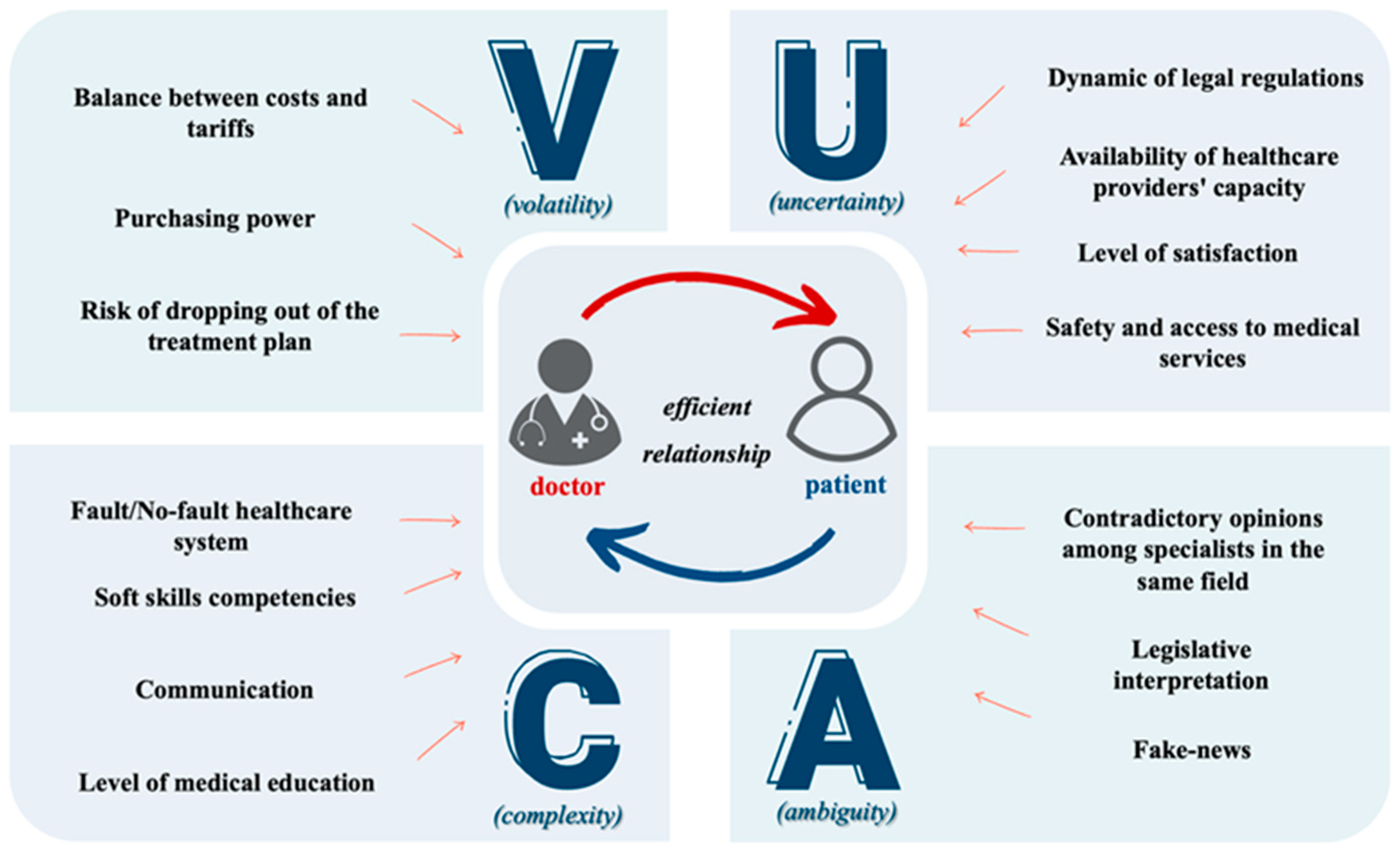

3.1. VUCA in Healthcare

3.1.1. Volatile Elements in Healthcare

3.1.2. Uncertain Elements in Healthcare

3.1.3. Complex Elements in Healthcare

- The no-fault system—The mechanism used in this system prioritizes the rapid compensation of patients harmed by medical acts, without the need to prove the guilt of the culprit, and promotes the idea of identifying the error and the conditions in which it occurred, in order to establish rules that would anticipate future error [21]. This system focuses on implementing a compensation model at a national level [22]. Countries such as Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and New Zealand have implemented such a system, which emphasizes extrajudicial procedures. This system has proven to be useful, as evidenced by the small number of malpractice cases that are resolved in court [23].

- The fault system—This system is used in the USA, most European Union states, and Romania. The compensation process for patients can be cumbersome due to the obligation to pursue and prove specific malpractice conditions, including the illicit act, the damage, the causal link, and the guilt [21,24]. Although mediation procedures are regulated by law, the community’s focus is primarily on punishing the presumed guilty party rather than compensating the harmed party. It is important to note that this mindset may hinder the effectiveness of mediation as a means of resolving disputes.

3.1.4. Ambiguous Elements in Healthcare

4. Discussion

4.1. VUCA Treatment in Healthcare

4.1.1. Vision in Healthcare

4.1.2. Understanding in Healthcare

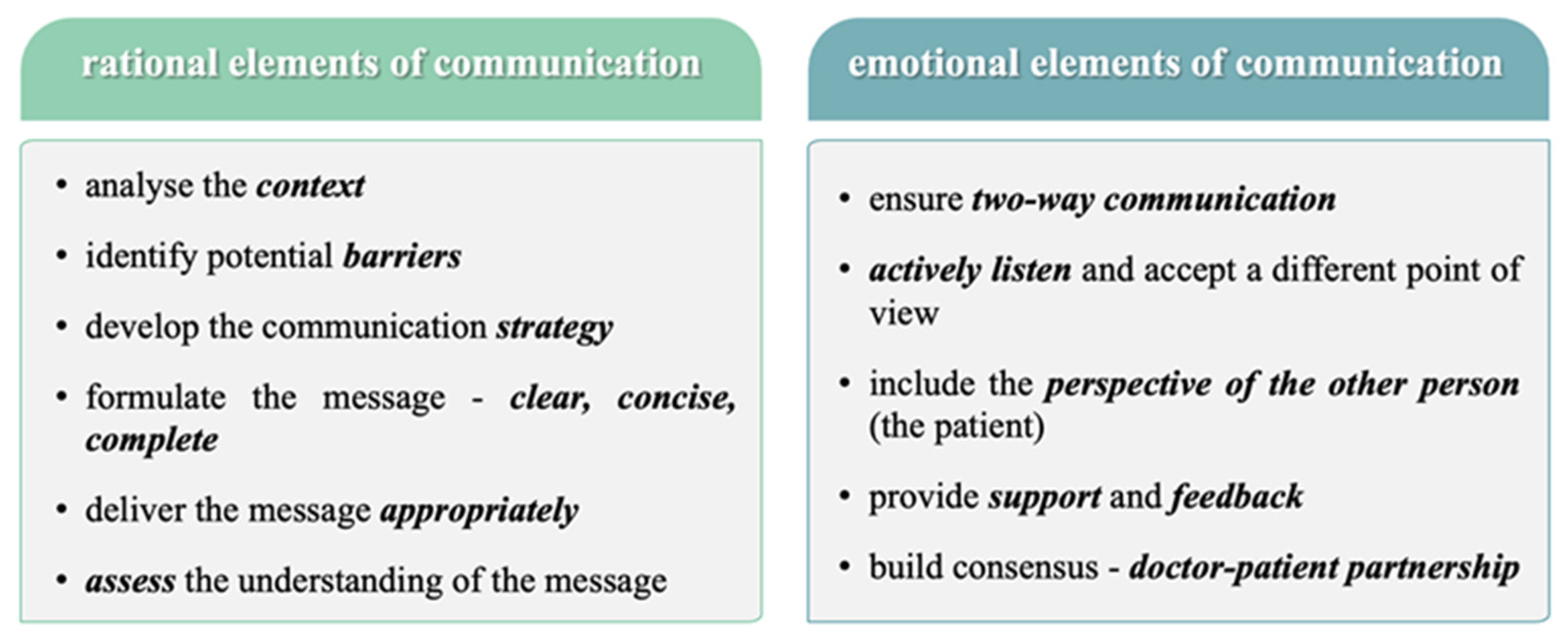

4.1.3. Clarity in Healthcare

4.1.4. Agility in Healthcare

5. Conclusions

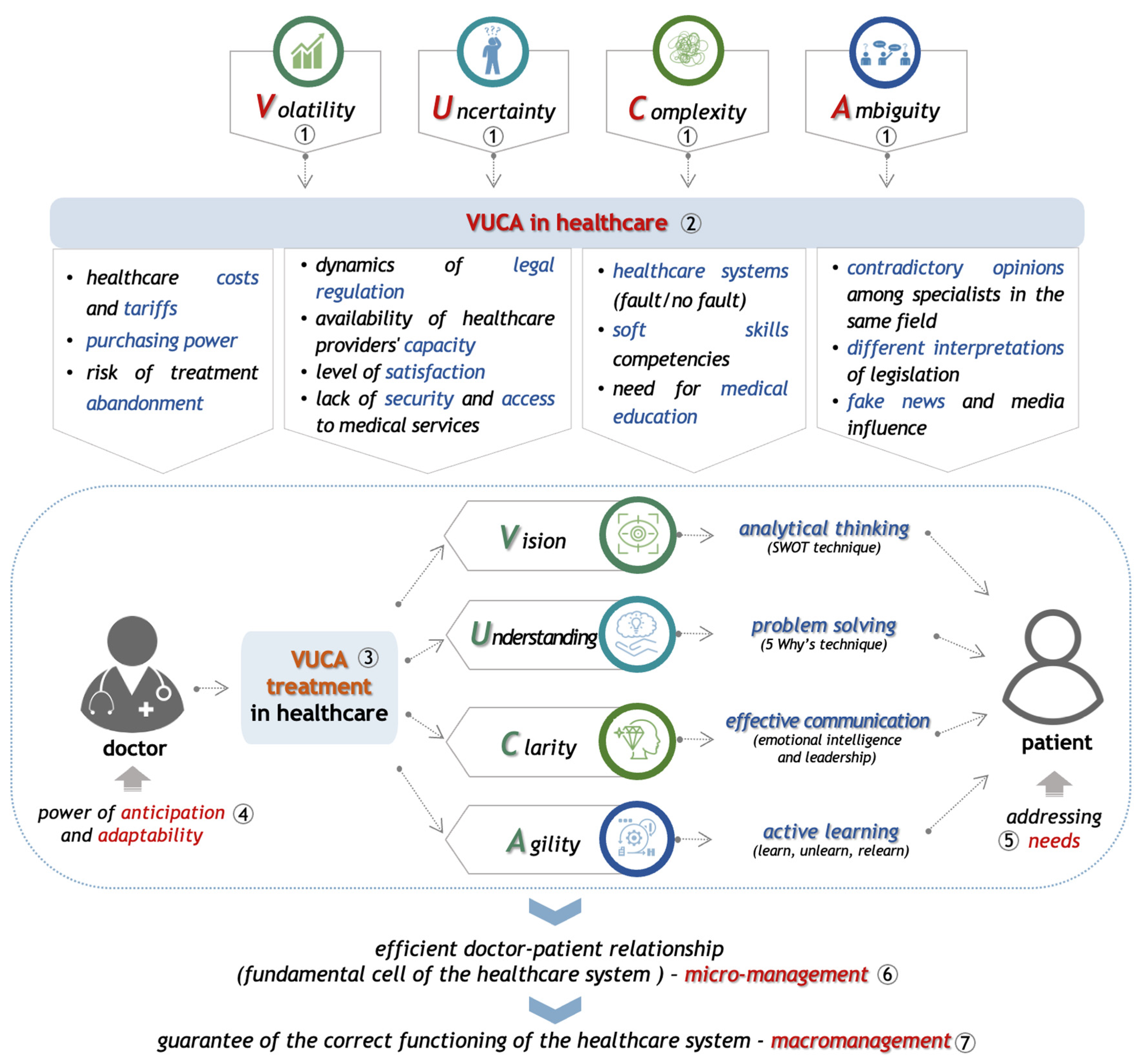

- Understanding the nature and functionality of the general characteristics of the constituent elements of VUCA—volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

- Healthcare professionals must have the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities to be aware of the specificity of the VUCA phenomenon in healthcare. The new VUCA dimension in healthcare thus represents an accumulation of elements and factors capable of influencing the professional activity of medical staff, the quality of the medical services provided, and the effectiveness of the relationship they build with their patients, with significant implications for the healthcare system as a whole.

- In order to mitigate the effects of this phenomenon, the doctor will apply the VUCA treatment in healthcare, which is a functional guide based on principles from which arises the need to acquire cross-functional competencies, whose applicability can be achieved through the use of efficient mechanisms and techniques capable of clarifying and reducing the crises and chaos created by VUCA. This can be achieved as follows:

- ▪

- Volatility will be countered by vision, which the doctor can achieve by developing analytical thinking; this defines his ability to understand the real context in which he operates, using the SWOT technique;

- ▪

- Uncertainty will be replaced by understanding, by developing the ability to solve problems efficiently, using techniques to identify the root cause and reduce the likelihood of recurrence, such as the “5 Why’s” technique;

- ▪

- Complexity is replaced by clarity, based on the doctor’s ability to communicate effectively (to listen and be understood) as an essential characteristic in the development of emotional intelligence and specific leadership skills to be applied in the relationship with the patient;

- ▪

- Ambiguity is replaced by the doctor’s agility, which is the result of the effort of active learning, ensuring a continuous process of “learning, unlearning, relearning”.

- Therefore, if we consider that VUCA is a certainty of the contemporary world that is intensifying year by year, the application of this treatment proves to be a necessity in the performance of the profession. This treatment ultimately supports the professional in developing two essential characteristics: anticipation and adaptability.

- This, in turn, offers the perspective of better understanding and addressing more easily the needs of the patient, as the real beneficiary of the health services and of all the efforts made at the system level.

- In this context, we can consider the doctor–patient relationship as efficient, representing the fundamental cell of the healthcare system, from the perspective of successful micro-management.

- This is therefore a guarantee of the correct functioning of the entire system at the level of macro-management applied to healthcare.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/human-rights/universal-declaration/translations/english (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Saleh, A.; Watson, R. Business excellence in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment (BEVUCA). TQM J. 2017, 29, 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, B.; Lemoine, J. What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseyin, Ç. VUCA Concept and Leadership. In Management & Strategy; Artikel Akademi: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taguma, M.; Gabriel, F. Future of Education and Skills 2030: Curriculum Analysis Preparing humanity for change and artificial intelligence: Learning to learn as a safeguard against volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. In Proceedings of the 8th Informal Working Group (IWG), Paris, France, 29–31 October 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/Preparing-humanity-for-change-and-artificial-intelligence.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Murugan, S.; Rajavel, S.; Aggarwal, A.; Singh, A. Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity (VUCA) in Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Challenges and Way Forward. Int. J. Health Syst. Implement. Res. 2020, 4, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, C.; Welker, A.; Kühn, A.; Schwertz, R.; Otto, B.; Moraldo, L.; Dentz, U.; Arends, A.; Welk, E.; Wendorff, J.-J.; et al. Public Health Leadership in a VUCA World Environment: Lessons Learned during the Regional Emergency Rollout of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccinations in Heidelberg, Germany, during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2021, 9, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horney, N.; Pasmore, B.; O’Shea, T. Leadership agility: A business imperative for a VUCA world. People Strategy 2010, 33, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, J.; De Paula, T. Events in VUCA Environments: Coping with the Covid-19 Pandemic in the Swedish event Industry (Dissertation). Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1678121/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- IESE Business School, University of Navarra. Keys to Beat Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity. Available online: https://www.iese.edu/insight/articles/volatility-uncertainty-complexity-ambiguity/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Taskan, B.; Junça-Silva, A.; Caetano, A. Clarifying the conceptual map of VUCA: A systematic review. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2022, 30, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.F.; De Mello Costa De Liberal, M.; Rached, C.D.A. Cost Management in a Multi-Professional Small-Scale Clinic of Popular Health Services. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–13. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/Cost-management-in-a-multi-professional-small-scale-clinic-of-popular-health-services-1939-4675-23-2-270.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Ferreira, D.C.; Marques, R.C.; Nunes, A.M. Pay for performance in health care: A new best practice tariff-based tool using a log-linear piecewise frontier function and a dual–primal approach for unique solutions. Oper. Res. Int. J. 2021, 21, 2101–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.; Marques, R.C. Do quality and access to hospital services impact on their technical efficiency? Omega 2019, 86, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branning, G.; Vater, M. Healthcare Spending: Plenty of Blame to Go Around. Am. Health Drug Benefits 2016, 9, 445–447. [Google Scholar]

- Maria, K.; Pinelopi, K.; Myria, I.; Ioannis, K.; Andrew, G. The Phenomenon of Treatment Dropout, Reasons and Moderators in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and other Active Treatments: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2019, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostin, L.O.; Monahan, J.T.; Kaldor, J.; DeBartolo, M.; Friedman, E.A.; Gottschalk, K.; Kim, S.C.; Alwan, A.; Binagwaho, A.; Burci, G.L.; et al. The legal determinants of health: Harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development. Lancet 2019, 393, 1857–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, A.; Sreeganga, S.D.; Ramaprasad, A. Access to Healthcare during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, N. Equity of access to health care: Some conceptual and ethical issues. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health Soc. 1982, 60, 51–81. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int. J. Health Serv. Plan. Adm. Eval. 1992, 22, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, K.; Kottenhagen, R. Patients’ Rights, Medical Error and Harmonisation of Compensation Mechanisms in Europe. Eur. J. Health Law. 2018, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, S.D.; Boscolo-Berto, R.; Viel, G. Malpractice and Medical Liability: European State of the Art and Guidelines; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gregorio, V.; Ferriero, A.M.; Specchia, M.L.; Capizzi, S.; Damiani, G.; Ricciardi, W. Defensive medicine in Europe: Which solutions? Vincenzo Di Gregorio. Eur. J. Public Health. 2015, 25, ckv171043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Romanian Civil Code. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/255190 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Moukalled, T.; Elhaj, A. Patient negligence in healthcare systems: Accountability model formulation. Health Policy Open 2021, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterick, T.E.; Patel, N.; Tajik, A.J.; Chandrasekaran, K. Improving health outcomes through patient education and partnerships with patients. Bayl. Univ. Med Cent. Proc. 2017, 30, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, W. The physician and patient education: A review. Patient Educ. Couns. 1986, 8, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanthakumari, S. Soft skills and its application in work place. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2019, 3, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Soft Skill Association. The Soft Skills Disconnect. Available online: https://www.nationalsoftskills.org/the-soft-skills-disconnect/ (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- ACOG. Committee Opinion No. 587: Effective Patient-Physician Communication. Obstet Gynecol. 2014, 123 Pt 1, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Mohammadnezhad, M. Doctor–Patient Communication in Primary Health Care: AMixed-Method Study in Fiji. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, C.J.; Stuntz, M.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y. Impact of adverse media reporting on public perceptions of the doctor-patient relationship in China: An analysis with propensity score matching method. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PEW Research Center. Internet Health Resources. 2003. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2003/07/16/internet-health-resources/ (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Melissa, T.; Leticia, B.; Emily, V. Mobilizing Users: Does Exposure to Misinformation and Its Correction Affect Users’ Responses to a Health Misinformation Post? Soc. Media + Soc. 2020, 6, 205630512097837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garattini, L.; Padula, A. Defensive medicine in Europe: A ‘full circle’? Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 165–170, Erratum in: Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, N.; Shynkarenko, V.; Kryvoruchko, O.; Zéman, Z. Enterprise management in VUCA conditions. Econ. Manag. Enterp. 2018, 170, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emet, G. SWOT ANALYSIS: A THEORETICAL REVIEW. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2017, 10, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, S. The Five Whys Technique. In Knowledge Solutions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyananda, P.L. Soft skills for physicians: Have we addressed it enough? J. Ceylon Coll. Physicians 2013, 44, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, S.D.; John, L.G. Motivational Determinants for Adult Learning. 1972. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED062602 (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Christine, C. Harvard Medical School. Available online: https://hms.harvard.edu/news/medicine-changing-world (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Joanna, D.; Patrick, L. Learning, Unlearning, and Relearning: Using Web 2.0 Technologies to Support the Development of Lifelong Learning Skills. In E-Infrastructures and Technologies for Lifelong Learning: Next Generation Environments; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiru, A.B. Half-Life Learning Curves in the Defense Acquisition Life Cycle. Def. ARJ 2012, 19, 283–308. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cernega, A.; Nicolescu, D.N.; Meleșcanu Imre, M.; Ripszky Totan, A.; Arsene, A.L.; Șerban, R.S.; Perpelea, A.-C.; Nedea, M.-I.; Pițuru, S.-M. Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity (VUCA) in Healthcare. Healthcare 2024, 12, 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070773

Cernega A, Nicolescu DN, Meleșcanu Imre M, Ripszky Totan A, Arsene AL, Șerban RS, Perpelea A-C, Nedea M-I, Pițuru S-M. Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity (VUCA) in Healthcare. Healthcare. 2024; 12(7):773. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070773

Chicago/Turabian StyleCernega, Ana, Dragoș Nicolae Nicolescu, Marina Meleșcanu Imre, Alexandra Ripszky Totan, Andreea Letiția Arsene, Robert Sabiniu Șerban, Anca-Cristina Perpelea, Marina-Ionela (Ilie) Nedea, and Silviu-Mirel Pițuru. 2024. "Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity (VUCA) in Healthcare" Healthcare 12, no. 7: 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070773

APA StyleCernega, A., Nicolescu, D. N., Meleșcanu Imre, M., Ripszky Totan, A., Arsene, A. L., Șerban, R. S., Perpelea, A.-C., Nedea, M.-I., & Pițuru, S.-M. (2024). Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity (VUCA) in Healthcare. Healthcare, 12(7), 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070773

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)