Mediation Role of Behavioral Decision-Making Between Self-Efficacy and Self-Management Among Elderly Stroke Survivors in China: Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. General Information Questionnaire

2.3.2. The Modified Rankin Scale (MRS)

2.3.3. The Stroke Self-Management Scale (SSMS)

2.3.4. The Stroke Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SSEQ)

2.3.5. The Behavioral Decision-Making Scale for Stroke Patients

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Demographic Characteristics

3.3. Correlations Among the Main Variables

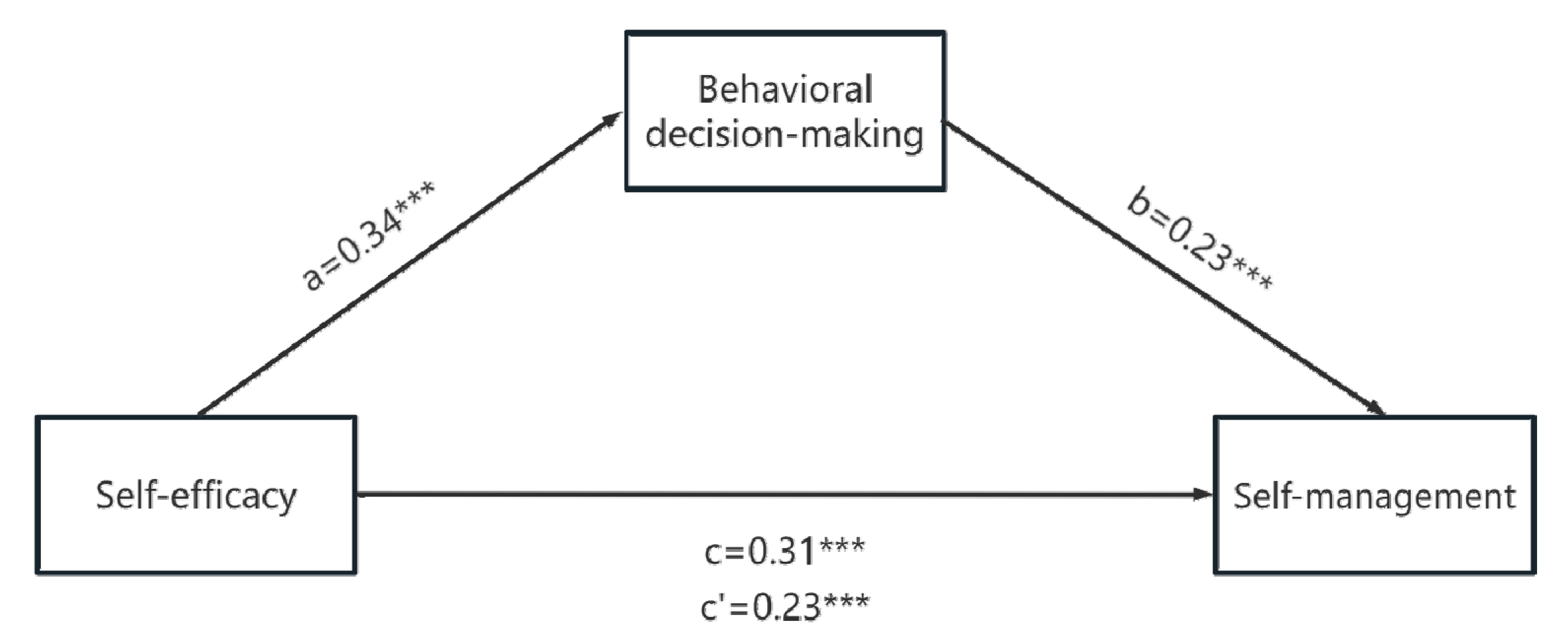

3.4. Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Stroke and Its Risk Factors, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Li, R.; Wang, L.; Yin, P.; Wang, Y.; Yan, C.; Ren, Y.; Qian, Z.; Vaughn, M.G.; McMillin, S.E.; et al. Temporal Trend and Attributable Risk Factors of Stroke Burden in China, 1990–2019: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. Public Health 2021, 6, e897–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report on Stroke Prevention and Treatment in China Writing Group. Brief report on stroke prevention and treatment in China, 2021. Chin. J. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 20, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, J.A.; Schepers, V.P.M.; Nijsse, B.; van Heugten, C.M.; Post, M.W.M.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A. The Influence of Psychological Factors and Mood on the Course of Participation up to Four Years after Stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reistetter, T.; Hreha, K.; Dean, J.M.; Pappadis, M.R.; Deer, R.R.; Li, C.-Y.; Hong, I.; Na, A.; Nowakowski, S.; Shaltoni, H.M.; et al. The Pre-Adaptation of a Stroke-Specific Self-Management Program Among Older Adults. J. Aging Health 2023, 35, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Li, X.; Marshall, I.J.; Bhalla, A.; Wang, Y.; O’Connell, M.D.L. Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms 10 Years after Stroke and Associated Risk Factors: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet 2023, 402 (Suppl. 1), S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, I.; Ariti, C.; Williams, A.; Wood, E.; Hewitt, J. Prevalence of Fatigue after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Stroke J. 2021, 6, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ory, M.G.; Ahn, S.; Towne, S.D.; Smith, M.L. Chronic Disease Self-Management Education: Program Success and Future Directions. In Geriatrics Models of Care: Bringing “Best Practice” to an Aging America; Malone, M.L., Capezuti, E.A., Palmer, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 147–153. ISBN 978-3-319-16068-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, C.C.; Oliveira, E.; Sousa, D.; Uba-Chupel, M.; Furtado, G.; Rocha, C.; Teixeira, A.; Ferreira, P.; Alves, C.; Gisin, S.; et al. Proceedings of the 3rd IPLeiria’s International Health Congress: Leiria, Portugal. 6–7 May 2016. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16 (Suppl. 3), 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pan, Q.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Q.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, M.; Guo, M. Status and influencing factors of health self-management in elderly stroke patients in Wuhan. Chin. J. Gerontol. 2017, 37, 4658–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska-Gieracha, J.; Mazurek, J. The Role of Self-Efficacy in the Recovery Process of Stroke Survivors. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer-Goossensen, D.; van Genugten, L.; Lingsma, H.F.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Koudstaal, P.J.; den Hertog, H.M. Self-Efficacy for Health-Related Behaviour Change in Patients with TIA or Minor Ischemic Stroke. Psychol. Health 2018, 33, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.P.; Barker, M. Why Is Changing Health-Related Behaviour so Difficult? Public Health 2016, 136, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, W. Behavioral Decision Theory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1961, 12, 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Jin, Y.; Mei, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Xue, L.; An, B. Preliminary Construction of Recurrence Risk Perception and Behavioral Decision Model in Stroke Patients. Mil. Nurs. 2024, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Zeng, S.; Ling, K.; Chen, S.; Yao, T.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Zhu, X. Experiences and Needs of Older Patients with Stroke in China Involved in Rehabilitation Decision-Making: A Qualitative Study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Maki, A.; Montanaro, E.; Avishai-Yitshak, A.; Bryan, A.; Klein, W.M.P.; Miles, E.; Rothman, A.J. The Impact of Changing Attitudes, Norms, and Self-Efficacy on Health-Related Intentions and Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cadilhac, D.A.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Mei, Y.; Ping, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lin, B. Developing a Chain Mediation Model of Recurrence Risk Perception and Health Behavior Among Patients With Stroke: A Cross-Sectional Study. Asian Nurs. Res. 2024, 18, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Lin, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Current situation of the health behavioral decision making in ischemic stroke patients and its influencing factors analysis. Chin. J. Nurs. 2024, 59, 2222–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurology, C.; Society, C. Diagnostic Criteria of Cerebrovascular Diseases in China (Version 2019). Chin. J. Neurol. 2019, 9, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N. The Sample Size Estimation in Quantitative Nursing Research. Chin. J. Nurs. 2010, 45, 378e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J. Cerebral Vascular Accidents in Patients over the Age of 60: I. General Considerations. Scott. Med. J. 1957, 2, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Ji, X.; Lan, L. The Application of mRS in the Methods of Outcome Assessment in Chinese Stroke Trials. Chin. J. Nerv.Ment. Dis. 2015, 41, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Construction and Application of Self-Management Intervention Project for Patients After Stroke. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, F.; Partridge, C.; Reid, F. The Stroke Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: Measuring Individual Confidence in Functional Performance after Stroke. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fang, L.; Bi, R.; Cheng, H.; Huang, J.; Feng, L. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Stroke Self Efficacy Questionnaire. Chin. J. Nurs. 2015, 50, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhang, Z.; Mei, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, P.; Tang, Q.; Guo, J.; Zhang, W. Development and psychometric test of the Behavioral Decision-making Scale for Stroke Patients. Chin. J. Nurs. 2022, 57, 1605–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye., B. Different Methods for Testing Moderated Mediation Models: Competitors or Backups? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuqi, H.; Siqin, L.; Xiaoyan, W.; Rong, Y.; Lihong, Z. The Risk Factors of Self-Management Behavior among Chinese Stroke Patients. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 2023, 4308517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Salcedo, A.; Dugravot, A.; Fayosse, A.; Jacob, L.; Bloomberg, M.; Sabia, S.; Schnitzler, A. Long-Term Evolution of Functional Limitations in Stroke Survivors Compared with Stroke-Free Controls: Findings from 15 Years of Follow-Up Across 3 International Surveys of Aging. Stroke 2022, 53, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhana, K.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Beck, T.; Holland, T.M.; Dhana, A.; Cherian, L.J.; Desai, P.; Evans, D.A.; Rajan, K.B. Lifestyle and Cognitive Decline in Community-Dwelling Stroke Survivors. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 89, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Chen, H.-X.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Z.-Y.; Zhou, C.-F.; Hu, X.-Y. Physical Activity as a Predictor of Activities of Daily Living in Older Adults: A Longitudinal Study in China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1444119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohle, E.; Lewis, B.; Agarwal, S.; Warburton, E.A.; Evans, N.R. Frailty Reduces Penumbral Volumes and Attenuates Treatment Response in Hyperacute Ischemic Stroke. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuelsson, C.M.; Hansson, P.-O.; Persson, C.U. Determinants of Recurrent Falls Poststroke: A 1-Year Follow-up of the Fall Study of Gothenburg. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Yuki, M.; Otsuki, M. Prevalence of Stroke-Related Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 105092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, R.M.; Gangwani, R.; Mark, J.I.; Fletcher, K.; Baratta, J.M.; Cassidy, J.M. Predictive Utility of Self-Efficacy in Early Stroke Rehabilitation. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2024, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Qiao, X.; Ji, L.; Si, H.; Bian, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, J.; et al. Association between Self-Efficacy and Self-Management Behaviours among Individuals at High Risk for Stroke: Social Support Acting as a Mediator. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. Self-Efficacy in the Adoption and Maintenance of Health Behaviors: Theoretical Approaches and a New Model. In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action; Hemisphere Publishing Corp: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 217–243. ISBN 978-1-56032-269-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, C.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Theadom, A. Exploring Facilitators and Barriers to Long-Term Behavior Change Following Health-Wellness Coaching for Stroke Prevention: A Qualitative Study Conducted in Auckland, New Zealand. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juavinett, A.L.; Erlich, J.C.; Churchland, A.K. Decision-Making Behaviors: Weighing Ethology, Complexity, and Sensorimotor Compatibility. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018, 49, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zeng, S.; Ling, K.; Chen, S.; Yao, T.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Zhu, X. A Qualitative Study on the Experience of Rehabilitation Decision-Making in Semi-disabled Elderly Patients with Stroke. J. Chengdu Med. Coll. 2024, 19, 342–346. [Google Scholar]

- Légaré, F.; Witteman, H.O. Shared Decision Making: Examining Key Elements and Barriers to Adoption into Routine Clinical Practice. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, B.J.; Turgeon, R.D. Incorporation of Shared Decision-Making in International Cardiovascular Guidelines, 2012–2022. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2332793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.J. Shared Decision-Making in Stroke: An Evolving Approach to Improved Patient Care. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2017, 2, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwyn, G.; Laitner, S.; Coulter, A.; Walker, E.; Watson, P.; Thomson, R. Implementing Shared Decision Making in the NHS. BMJ 2010, 341, c5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukasczik, M.; Wolf, H.D.; Vogel, H. Development and Initial Evaluation of the Usefulness of a Question Prompt List to Promote Patients’ Level of Information about Work-Related Medical Rehabilitation: A Pilot Study. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2024, 5, 1266065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.; Jafari, Z.; Rakhshan, M.; Yarahmadi, F.; Zonoori, S.; Akbari, F.; Moghimi, E.S.; Amirmohseni, L.; Abbasi, M.; Sharstanaki, S.K.; et al. Application of Orem’s Theory-Based Caring Programs among Chronically Ill Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 70, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Tao, Q.; Zhou, X.; Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L.; Tao, J.; Chan, C.C. Patient and Family Member Factors Influencing Outcomes of Poststroke Inpatient Rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 249–255.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | n (%) | Self-Management [M(P25, P75)] | Z/H |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 195 (67.01) | 174 (157, 193) | −2.504 * |

| Women | 96 (32.99) | 187.5 (161.25, 209.5) | ||

| Marriage | Married | 259 (89.00) | 180 (157, 198) | −0.006 |

| Divorced | 32 (11.00) | 174 (158, 203) | ||

| Residential area | Rural | 108 (37.11) | 191 (165, 209.5) | −4.288 *** |

| Urban | 183 (62.89) | 170 (156, 191.25) | ||

| Working state | Unemployed | 105 (36.08) | 184 (163, 201.75) | 12.514 ** |

| Pensioner | 84 (28.87) | 189.5 (149.25, 211.75) | ||

| Working | 102 (35.05) | 164.5 (157, 190.25) | ||

| Educational level | Primary or below | 112 (38.49) | 171 (156, 191) | −0.010 |

| Junior high school | 78 (26.80) | 177 (156, 201) | ||

| High school | 79 (27.15) | 186 (161, 198) | ||

| University or above | 22 (7.56) | 208 (182.25, 225.25) | ||

| Number of strokes | 1 | 156 (53.60) | 188 (162, 200) | 9.117 * |

| 2 | 95 (32.65) | 165 (156, 191) | ||

| 3 or more | 40 (13.75) | 169 (144, 192) | ||

| Duration of stroke | <3 months | 55 (18.90) | 188 (159, 208) | 3.988 |

| 3 months~ | 131 (45.02) | 176 (160, 193) | ||

| 1 year~ | 44 (15.12) | 172.5 (146.75, 199.75) | ||

| 3 years or more | 61 (20.96) | 182 (156.25, 212) | ||

| Family history of stroke | Yes | 58 (19.93) | 181 (146.75, 205) | −0.344 |

| No | 233 (80.07) | 177 (159, 197.75) | ||

| Type of stroke | Ischemic | 239 (82.13) | 177 (157, 196) | −2.043 * |

| Hemorrhagic | 52 (17.87) | 189 (162, 208) | ||

| mRS (scores) | <3 | 243 (83.51) | 184 (158, 198) | −1.708 |

| ≥3 | 48 (16.49) | 172 (153.25, 185) | ||

| Number of chronic diseases | 1 | 16 (5.50) | 191 (159.5, 193.75) | 15.343 *** |

| 2 | 173 (59.45) | 172 (156, 192.5) | ||

| 3 | 56 (19.24) | 175 (156.25, 201.5) | ||

| 4 or more | 46 (15.81) | 199 (175.5, 212) | ||

| ADL | 40~ | 9 (3.09) | 176 (151.5, 207) | −0.010 |

| 60~ | 282 (96.91) | 178.5 (158, 198) |

| Regression Equation | Global Fit Index | Significance of Regression Coefficient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | Predictor variable | R | R2 | F | B (95% CI) | t |

| Self-management | Gender | 0.51 | 0.26 | 14.21 | 0.16 (−0.05, 0.37) | 1.51 |

| Residential area | 0.34 (0.14, 0.54) | 3.33 ** | ||||

| Working state | −0.17 (−0.29, −0.05) | −2.88 ** | ||||

| Number of strokes | −0.14 (−0.28, −0.01) | −2.02 * | ||||

| Type of stroke | 0.20 (−0.05, 0.46) | 1.58 | ||||

| Number of chronic diseases | 0.18 (0.06, 0.30) | 2.92 ** | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.31 (0.22, 0.41) | 6.50 *** | ||||

| Behavioral decision-making | Gender | 0.41 | 0.17 | 14.98 | 0.28 (0.03, 0.53) | 2.19 * |

| Residential area | 0.36 (0.12, 0.60) | 2.94 ** | ||||

| Working state | −0.01 (−0.15, 0.13) | −0.16 | ||||

| Number of strokes | 0.18 (0.01, 0.35) | 2.12 * | ||||

| Type of stroke | 0.22 (−0.09, 0.52) | 1.41 | ||||

| Number of chronic diseases | −0.13 (−0.27, 0.02) | −1.73 | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.34 (0.23, 0.46) | 5.98 *** | ||||

| Self-management | Gender | 0.56 | 0.32 | 16.28 | 0.10 (−0.11, 0.30) | 0.94 |

| Residential area | 0.26 (0.06, 0.46) | 2.58 * | ||||

| Working state | −0.17 (−0.28, −0.06) | −2.94 ** | ||||

| Number of strokes | −0.19 (−0.32, −0.05) | −2.68 ** | ||||

| Type of stroke | 0.15 (−0.09, 0.40) | 1.23 | ||||

| Number of chronic diseases | 0.21 (0.09, 0.33) | 3.51 ** | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.23 (0.14, 0.33) | 4.75 *** | ||||

| Behavioral decision-making | 0.23 (0.14, 0.33) | 4.80 *** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Kevine, N.T.; An, B.; Ping, Z.; Lin, B.; Zhang, Z. Mediation Role of Behavioral Decision-Making Between Self-Efficacy and Self-Management Among Elderly Stroke Survivors in China: Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070704

Wang X, Jiang H, Zhao Z, Kevine NT, An B, Ping Z, Lin B, Zhang Z. Mediation Role of Behavioral Decision-Making Between Self-Efficacy and Self-Management Among Elderly Stroke Survivors in China: Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):704. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070704

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaoxuan, Hu Jiang, Zhixin Zhao, Noubessi Tchekwagep Kevine, Baoxia An, Zhiguang Ping, Beilei Lin, and Zhenxiang Zhang. 2025. "Mediation Role of Behavioral Decision-Making Between Self-Efficacy and Self-Management Among Elderly Stroke Survivors in China: Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070704

APA StyleWang, X., Jiang, H., Zhao, Z., Kevine, N. T., An, B., Ping, Z., Lin, B., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Mediation Role of Behavioral Decision-Making Between Self-Efficacy and Self-Management Among Elderly Stroke Survivors in China: Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(7), 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070704