Abstract

The objective of this work was to identify available evidence on nursing interventions for the prevention and treatment of phlebitis secondary to the insertion of a peripheral venous catheter. For this, a scoping systematic review was carried out following the guidelines in the PRISMA declaration of documents published between January 2015 and December 2020. The search took place between December 2020 and January 2021. Scielo, Pubmed, Medline, Scopus, WOS, CINHAL, LILACS, and Dialnet databases were consulted, and CASPe, AGREE, and HICPAC tools were used for the critical reading. A total of 52 studies were included to analyze nursing interventions for treatment and prevention. Nursing interventions to prevent phlebitis and ensure a proper catheter use included those related to the maintenance of intravenous therapy, asepsis, and choosing the dressing. With regard to the nursing interventions to treat phlebitis, these were focused on vigilance and caring and also on the use of medical treatment protocols. For the prevention of phlebitis, the highest rated evidence regarding asepsis include the topical use of >0.5% chlorhexidine preparation with 70% alcohol or 2% aqueous chlorhexidine, a proper hygienic hand washing, and the use clean gloves to handle connections and devices. Actions that promote the efficacy and safety of intravenous therapy include maintenance of venous access, infusion volume control, verification of signs of phlebitis during saline solution and medication administration, and constant monitoring. It is recommended to remove any catheter that is not essential. Once discharged from hospital, it will be necessary to warn the patient about signs of phlebitis after PVC removal.

1. Introduction

Vascular access cannulation through the use of peripheral venous catheters (PVCs) is a common practice and is considered the most common invasive procedure performed on hospitalized patients [1]. This technique allows quick access to the vascular system, being less invasive and less complex than other techniques [1,2,3]. The type of catheter is chosen based on the estimated duration and type of treatment to be infused, and among the uses of PVCs are fluid therapy, parenteral nutrition, blood products, and diagnostic tests [4].

The most common side effect of PVC is phlebitis [5]. This consists of acute inflammation of the wall of the blood vessels, with irritation of the venous endothelium in the section or segment cannulated by the catheter [6]. Identification of phlebitis requires assessment of possible signs and symptoms present in the insertion area, such as erythema, tumefaction in the vein, pain, heat, and fever [7]. In this sense, the use of rating scales such as the Visual Infusion Phlebitis (VIP) scale, the Phlebitis scale, and the Maddox scale [8,9,10] may be useful.

In Spain, up to 30% of the bacteriaemia associated with hospital care is related to the use of intravascular devices, and these produce increased morbidity and hospital expenses, which are estimated at around 18,000 euros per episode [4].

PVC management is an under-recognized issue regarding patient risk within the complexity of care [11]. It was verified through the National Study of Adverse Events (ENEAS, for its acronym in Spanish) that if phlebitis is included as an adverse healthcare event, it would rank first followed by medication errors, infections arising from healthcare-related practices, and surgical techniques [7]. On the other hand, the SENECA Project: Quality of care standards for patient safety in National Health System hospitals, enabled from 1344 revised medical records, from 32 different hospitals, identified approximately 377 patients who developed phlebitis and/or extravasation (25.1%) [7]. Phlebitis prolongs hospitalization and treatment, increases economic expenses, decreases patient satisfaction, and can lead to other complications such as sepsis, pain, discomfort, stress, possibility of clotting, thrombophlebitis, and embolism [5,12,13].

The Infusion Nurses Society (INS) [9] indicates that the accepted phlebitis rate should be 5% or less [14,15]. Currently, a phlebitis incidence of 0.5% to 59.1% [5] is estimated, with a prevalence of between 20 and 80% of patients following intravenous treatment [16].

Nurses’ knowledge on the proper management of PVC and early recognition of risk factors can reduce these complications [14,17]. In Spain, it is a nursing competence, collected in Order CIN/2134/2008, of 3 July [18]. In addition, the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA-I) collects a risk diagnosis to prevent risk of (00213) phlebitis, and the Nursing Intervention Classification (NIC) establishes interventions for the prevention and treatment of phlebitis such as (4200) Intravenous therapy (iv); (2314) Medication administration: intravenous (iv); and (4235) Phlebotomy: Cannulated Vessel [19,20].

For this reason, the objective of this review was to identify available evidence on nursing interventions for the prevention and treatment of phlebitis secondary to the insertion of a peripheral venous catheter.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

A systematic scoping review [21] of the literature was carried out, following the standards set out in the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [22]. Based on the PICO format (Table 1), the following research question was developed: What are the evidence-based nursing interventions for the prevention and treatment of phlebitis in patients with PVC?

Table 1.

PICO.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search was performed between December 2020 and January 2021 (Table 2). The databases consulted were Scielo, Pubmed, Medline, Scopus, WOS, CINHAL, LILACS, and Dialnet using MeSH and DeCS descriptors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Search strategy.

2.3. Selection Criteria

The search was limited to full-text documents, in Spanish, English, and/or Portuguese, published in the last 5 years. These included empirical studies and clinical guidelines that focused on phlebitis, its classification, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment from the nursing competence perspective. Those that, during the critical reading, did not meet the expected criteria in the first three questions of the CASPe [23] tool nor of Berra et al.’s instrument [24] for descriptive articles were excluded. Articles not available in full text and published in languages other than Spanish, English, or Portuguese were also excluded.

Following the recommendations for improvement for Scoping Reviews by Levac, Colquon, and O’Brien [25], it was decided not to discriminate by type of study in the selection. In the classification and presentation of results, we differentiate according to the design of the selected studies.

2.4. Data Collection and Extraction

The search was conducted independently and pooled by the researchers as detailed in the Authors Contributions. The authors performed an evidence synthesis by peer evaluation, analyzing each intervention and evidence individually, following the criteria provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). The discrepancies were jointly discussed to reach consensus on the degree of evidence (DE) and the degree of recommendation (DR).

2.5. Evaluation of Methodological Quality

Once the titles and summaries of the articles were critically read, data were classified according to the objectives of the study. The included full-text articles were assessed with the CASPe [23] and Berra et al.’s [24] tools. For clinical practice guidelines, AGREE [26] was used for critical reading and the HICPAC system for evidence synthesis [27]. The JBI [28] criteria were used to classify the degree of evidence (DE) and the degree of recommendation (DR) of nursing interventions.

3. Results

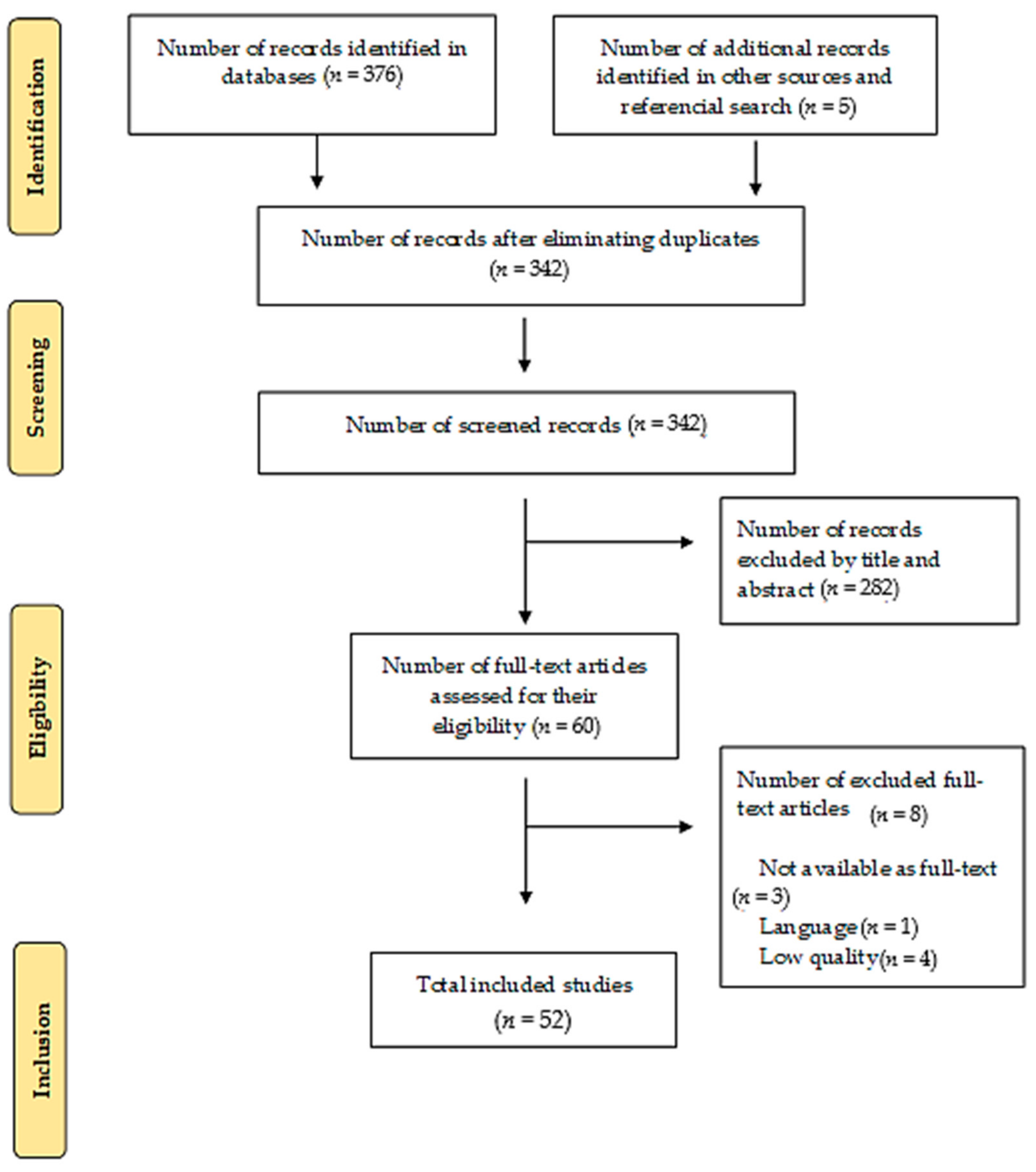

The number of records identified in the databases was 376, to which five more records were added by referential search to introduce the clinical practice guidelines, for a total of 381 references. Of the 381 identified references, 52 studies were finally selected according to eligibility criteria (Figure 1) [22].

Figure 1.

Search results (PRISMA flowchart).

In terms of typology, 9 randomized clinical trials, 17 cohort studies, 8 systematic reviews, 3 case and control studies, 1 qualitative study, 10 descriptive studies, and 4 clinical practice guidelines, out of the total of 52 selected studies were included. Table 3 lists the characteristics of the studies included in the scoping review classified according to the type of article.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies included in the scoping review.

The articles are classified as nursing interventions for the prevention of phlebitis or for the treatment of phlebitis, both for nurses who apply care independently and for nurses that follow guidelines and protocols.

3.1. Nursing Interventions for the Prevention of Phlebitis

Management and maintenance of intravenous therapy

- Protocol monitoring and continuous evaluation [28,29].

- Records need to include date of puncture, dressings used, professional performing the procedure, date of change of PVC, puncture locations, number of puncture attempts, intravenous medication in use, change of dressing, and next check-up [4,44].

- For intermittent flushing and locking of PVC, it is recommended to use saline solution (SS) before and after administration of medication by performing the positive pressure technique [4,29]. According to the Flebitis Zero project, flushing heparin is not recommended because it can cause thrombocytopenia [7]. A randomized clinical trial reflected that continuous infusion of heparin into PVCs improved the duration of permeability, reducing infusion failure and phlebitis. However, no statistically significant differences were found when heparin was used intermittently. If PVC is used to obtain a blood sample, the use of diluted heparin is indicated [43]. Double-pump syringes enable both medication and cleaning solution administration to reduce PVC manipulation and complications [40].

- To prevent and treat phlebitis, Aloe vera, Matricaria chamomilla, and Xianchen (composed of some components such as Fritillaria and Bletilla striata) can be used. The application of Moist Exposed Burn Ointment (MEBO) for topical treatment of burn injuries, containing sesame oil, β-sitosterol, Berberine, and other medicinal plants (Coptis chinensis, Scutellaria baicalensis, Phellodendron chinese, and Papaver somniferum) [36] is also effective.

- Remove peripheral venous catheters if the patient develops signs of phlebitis (warmth, tenderness, erythema, or palpable venous cord), infection, or a malfunctioning catheter [7,45].

- Not performing a systematic catheter change every 72 to 96 h. It must be changed when clinically justified. There are no significant differences in the percentage of complications (phlebitis, occlusion...) between PVC that have been inserted less than 96 h and those that have been inserted for more than 96 h [4,46,47].

- Avoiding insertion into joint areas, wrist, and antecubital fossa, because there is a higher incidence of mechanical phlebitis related to catheter movement [4].

- Replacing administration systems, extension cords, and accessories with a frequency of more than 96 h and less than 7 days, when dirty or damaged connections are observed, and whenever there is an accidental disconnection of the circuit [4].

- Withdrawing systems of blood administration and of blood products at the end of transfusion [4].

- In adults, an upper-extremity site for catheter insertion must be used. Any catheter inserted in a lower extremity must be replaced to an upper extremity site as soon as possible [4].

- Using a 0.22-micron line filter to remove air and bacteria and small drug particles that were not properly diluted. A filter is also required when the infusion of amiodarone exceeds 24 h [48].

- Guiding patients and family members on signs and symptoms of phlebitis, during infusion and post-infusion after extraction of PVC [2,31]. Educating patients on the fact that ensuring proper care of PVC helps reduce risk of infection [17].

3.2. Asepsis

- Using alcoholic chlorhexidine solution at > 0.5% or aqueous chlorhexidine at 2%. In cases of hypersensitivity, iodine solutions or alcohol at 70% may be used [4,17].

- Applying antiseptics to clean skin and complying with drying times (2% alcoholic chlorhexidine: 30 s; non-alcoholic chlorhexidine and povidone–iodine: 2 min) [4].

- Hygienic hand washing and usage of clean gloves for both punctures and equipment, hubs, stopcocks, and bio-connectors handling. It is not necessary to wear sterile gloves if the previously disinfected area is not touched again during the technique [4]. Using disposable tourniquets can help reduce PVC contamination rates [49].

- Minimizing handling of connectors for infusion equipment [4].

- Protecting dressing and connectors in activities that may pose a risk of contamination [4].

- High incidence of phlebitis and infection of inserted PVCs has been found in emergency areas. In these cases, it is recommended to replace the catheter within the first 48 h if aseptic technique could not be ensured [7,41].

3.3. Nursing Assessment

- Involving the patient in the choice of PVC and puncture site [2].

- Analyzing patient characteristics, prescribed medications (irritant and/or vesicant, pH, and osmolarity), expected duration of the treatment, and other risk factors for the onset of phlebitis, before opting for a PVC [4,30].

- Assessing the status of venous resources. Whenever possible, choose straight, palpable, and well-filled vessels [4].

- Keeping the PVC insertion site visible [40,45]. Developing an observation table to document the development of signs of phlebitis for early detection and decreased discomfort and pain [50].

- Previously identifying comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus due to the changes in the circulatory system caused by this disease [31].

- Asking the patient if there is pain/discomfort, heat, or burning at the insertion site [32].

3.4. Catheter

- Selecting the length and caliber of the catheters based on objective, expected time of use, known infectious or non-infectious complications, experience of those who insert and manage the catheter [7].

- Selecting a catheter of the least length and caliber possible, not exceeding the caliber of the chosen vessel, to allow blood to pass into the vessel and favor the hemodilution of the preparations to be infused [4,45].

- Using the minimum number of three-way stopcocks. Idle ports should always be capped [4].

- Using only one of the ports of the three-way stopcock to place a bio-connector, where medication solutions and bolus will be administered. The results of a prospective experimental study indicate that using SwabCap significantly reduced connector contamination from 43.7% to 0% (p = 0.006) [51]. If this cap is not available, the bio-connector is disinfected with alcoholic chlorhexidine at >0.5% or 70% alcohol for 30 s [4,7].

- Teflon, silicone, or polyurethane elastomer catheters are safer than those of polyethylene, polyvinyl hydrochloride, or steel needles, which might cause tissue necrosis if extravasation occurs [43].

3.5. Dressing

- It is not advisable to bandage the site of the intravenous line. Sterile, transparent [45], semipermeable adhesive dressing will be used to improve visibility of the insertion site [7,32,52].

- The dressing should be placed aseptically, with clean or sterile gloves, without excessively touching the adhesive layer and without placing tie-shaped adhesive tapes under the dressing. Wear sterile gloves for central and arterial devices [4].

- Changing dressings at least every 7 days, except in pediatric patients, where the risk of moving the catheter is greater than the advantages derived from changing the dressing [7]. Routine dressing change is not recommended, as it increases the risk of colonization at the puncture site [49].

- Replacing catheter site dressing if the dressing becomes damp, loosened, or visibly soiled [7].

- If the site is bleeding or oozing, use gauze dressing until this is resolved [4].

- Ensuring correct securement or dressing to prevent dislodgement [4].

- Softly removing dressing, without moistening the puncture site [4].

- For catheter securement, products such as CliniFix simultaneously reduce the risk of infection and trauma from cannula movement. Made with hydrocolloid adhesive, not harmful to the skin, that can remain in place for up to 7 days without affecting the integrity of the skin. In the presence of wound oozing, hydrocolloids absorb fluid and form gel to help reduce the spread of infection [42].

- Using skin glue (cyanoacrylate) at the insertion site to improve catheter securement and reduce rates of phlebitis and occlusion. Apply a drop at the insertion site and a drop under the center of the catheter, allow to dry for 30 s, and place a dressing [33].

- Using the “I.V. House UltraDressing” in pediatric patients to increase catheter dwell time, and to protect and stabilize PIVCs [34].

3.6. Nursing Interventions for the Treatment of Phlebitis

Nurse as a care prescriber

- Apply alternating hot and cold compresses to decrease erythema, edema, and pain. The hot compress stimulates vasodilation by inducing optimal blood circulation and promoting a faster wound-healing process. The cold compress stimulates vasoconstriction and reduces edema [35].

- Apply compresses with 0.9% NaCl to stimulate anti-inflammatory response and relieve pain, redness, swelling, and edema [35].

- Apply 10 drops (3 mL) of sesame oil (SO) twice daily for two weeks. Massage for 5 min within 10 cm of the place of phlebitis. Use a finger with a sterile glove to apply a rotary technique. SO contains unsaturated fatty acids (linoleic acid, oleic acid) that relieve pain by reducing prostaglandins and leukotriene. In addition, the SO has lignans responsible for analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects [36].

- Administer chamomile extract (2.5%), as it has anti-inflammatory and anti-edema properties. It is the most effective in the treatment of grade II phlebitis. The use of topical chamomile showed that the incidence of phlebitis in patients treated with amiodarone decreases significantly. Aqueous chamomile extract inhibits the production of prostaglandins by the suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and direct gene expression of inhibition of COX-2 enzyme activity [37].

- Apply a compress with Burow solution at a temperature between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius, and leave on for 20 min every 8 h. This formulation has as its main component aluminium acetate, which is known for its astringent properties and ability to produce the precipitation of proteins at the topical level. Based on observed results, the Burow solution could be defined as an effective therapeutic alternative in the treatment of post-infusion phlebitis [38].

- Apply marigold ointment every 8 h. Calendula/marigold flavonoids prevent histamine release and prostaglandin production. In addition, they inhibit blood plasma secretion in tissues, reduce the migration of white blood cells to the swelled area, and prevent the growth of bacteria and fungi by reducing capillary permeability. In one study, the application of marigold ointment decreased the severity of phlebitis in a shorter period compared to using a wet and hot compress. It is proven to have anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects. Although calendula has an anti-inflammatory effect similar to corticoids, it has none of its complications and is safe to use [39].

3.7. Nurses Following Protocols and Guidelines

- Topical treatments with Aloe vera or “Chamomilla Recutita” using wet compresses at 38 degrees Celsius on the affected area. Apply topical diclofenac and "Essaven" heparin gel. Other topical products such as notoginseny and 5 mg nitroglycerin patch accelerate the improvement of phlebitis symptoms, as compared to heparinoid substances [6].

- Dilution of chemotherapeutic agents, immediate catheter removal, intermittent heparin washing, prophylactic antibiotics, transparent dressings, topical application of anti-inflammatory or corticosteroid agents, and application of a hot and/or wet compress are preventive and therapeutic approaches [36].

- There is no definitive treatment to prevent phlebitis; drugs such as heparin, corticosteroids, and piroxicam have been proposed as therapeutic agents [39].

In addition, Table 4 identifies the interventions found in the literature, their evidence synthesis, and their correspondence with NIC nursing interventions.

Table 4.

Correspondence with NIC interventions and DE and DR analysis with JBI.

4. Discussion

The objective of this review was to identify available evidence on nursing interventions for the prevention and treatment of phlebitis secondary to the insertion of a peripheral venous catheter.

For the prevention of phlebitis, the greatest evidence found regarding asepsis is to use >0.5% chlorhexidine preparation with alcohol or 2% aqueous chlorhexidine, perform hygienic hand washing, and use clean gloves to handle connections and stopcocks (category AI). Regarding the maintenance of PVC, the interventions with the greatest evidence (category IA) are replacing extensions and administration sets between 4 and a maximum of 7 days if they are not loosened or soiled, and using the fewest three-way stopcocks, one of the ports with a bio-connector, and having the others capped [4]. Actions that promote the efficacy and safety of intravenous therapy include maintenance of access, infusion control, verification of signs of phlebitis during saline solution replacement and medication administration, and constant monitoring [53,54]. It is recommended to remove any catheter that is not essential (Category IA) [7]. Once discharged from hospital, it will be necessary to warn the patient about signs of phlebitis after PVC removal [2] (DE 1a).

Regarding the dressing, the greatest evidence obtained is the use of “IV House UltraDressing” in pediatric patients to increase dwell time and stabilize the catheter [34] (DE IA). The dressing must be sterile, transparent, and semi-permeable for continuous visual inspection of the catheter site [7] (Category IA). A novel technique is the use of medical grade cyanoacrylate for catheter securement to reduce rates of phlebitis [33] (DE 1c).

Vein quality control through palpation and visual inspection can prevent phlebitis as well as the nurse’s duration of hand hygiene and the clinical experience [55]. Regarding the choice of veins, a controversy has been found, as some studies recommend the forearm as it has a larger diameter and this reduces rates of phlebitis in the region, but there are many others that claim that this region should be avoided, in addition to the joints and wrist areas (category IA), for having a higher incidence of mechanical phlebitis related to catheter movement [4,56]. A review of the literature concluded that veins from the antecubital region are associated with lower rates of phlebitis, as compared to veins in the hands. Therefore, although the back of the hand is considered an easily accessible venous place, it is not indicated for prolonged venous therapy, and nurses are believed to need to be trained in carrying out alternatives such as jugular vein venipuncture that has very low rates of prevalence of phlebitis [44].

Although some studies, such as the one conducted by Circolini et al. (cited in Wei et al. [57]), in which Cox’s analysis was used, showed that as the PVC’s dwell time increased by 24 h, the risk of phlebitis also did so with an odds ratio of 1.05. Webster et al.’s [46] team concluded in their clinical trial review that the catheter should be removed only when clinically indicated, evaluating at every new shift to identify signs of phlebitis [46,57,58] early.

There are higher rates of phlebitis when larger caliber catheters are used, as they increase attraction to the vessel wall, so the smallest possible length and caliber catheters (Category IB) are recommended [4,56].

The nurse’s clinical judgment regarding the selection of a PVC should also involve assessing comfort, anxiety, and restrictions in the patient’s day-to-day activities. The number of venipuncture attempts is one of the quality indicators and shows patient satisfaction for its sensory impact [59].

For the control and management of intravenous therapy, nurses should carry out a protocol that includes recording all aspects related to the catheter and its maintenance (DE 4a and DR A) [28].

According to the studies consulted, the data show a higher proportion of complications in peripheral venous catheters among women (p = 0.0300), patients 85 years of age or older as compared to those under 65 (p = 0.0500), and when puncturing the forearm region as compared to other regions (p ≤ 0.0001) [60].

Regarding saline flush, the effectiveness and safety of a solution of 0.9% of sodium chloride was compared with heparin saline solution, and it was concluded that both agents are equally effective and safe [14]. However, flushing PVC with normal saline prevents the accumulation of bacteria, proteins, and platelets suspended in plasma; therefore, saline flush prevents and reduces phlebitis [13] (DE 1c).

It is necessary to check that the prescription of intravenous medication can be administered peripherally, as many of these drugs are irritating. Regular evaluation is key to the prevention and early detection of intravenous complications (DE 5a) [30,61].

In case the patient has phlebitis, nursing interventions with more evidence in their application are Moist Exposed Burn Ointment (MEBO) for topical treatment of burn injuries, Aloe vera, chamomilla recutita in wet compresses, topical diclofenac, “Essaven” heparin gel, notoginseny, and 5 mg nitroglycerin patch and anti-inflammatory or corticosteroids in a hot or wet compress (DE 1a) [6,36]. On the other hand, the application of marigold ointment, piroxicam, and sesame oil has an evidence level of 1C [36,39].

Some limitations of this bibliographic review are the little available evidence on the use of Burow’s solution as a treatment for phlebitis, despite its usual use in hospitals. This review may contain limitations inherent to the search and selection process. Therefore, we believe that further research and systematic review of the findings is needed.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this review includes evidence-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of phlebitis associated to the venous catheter. The need for nursing training on the latest available evidence regarding the use and management of venous catheters is highlighted. It is important that hospitals implement projects such as “Flebitis Zero” so that nurses can rely and base their knowledge on them, thus providing quality care to patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Data curation, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G. and G.D.-C.; Formal analysis, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Investigation, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Methodology, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Project administration, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G. and G.D.-C.; Resources, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Software, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Supervision, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Validation, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Visualization, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Writing—original draft, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C.; Writing—review and editing, A.G.-S., M.B.S.-G., M.E.C.-P., J.Á.R.-G., J.G.-S. and G.D.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available within this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank to the School of Nursing Nuestra Señora de Candelaria of Tenerife, Spain, its teachers and board of directors, for their collaboration for the development of this Final Degree Project, as well as for their educational and socializing work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Urbanetto, J.S.; Peixoto, C.G.; May, T.A. Incidencia de flebitis durante el uso y después de la retirada de catéter intravenoso periférico. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem 2016, 24, e2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro-Oliveira, A.S.; Basto, M.L.; Braga, L.M.; Arreguy-Sena, C.; Melo, M.N.; Parreira, P.M. Nursing practices in peripheral venous catheter: Phlebitis and patient safety. Texto Contexto-Enferm 2019, 28, e20180109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enes, S.M.S.; Opitz, S.P.; Faro, A.R.M.d.C.d.; Pedreira, M.d.L.G. Phlebitis associated with peripheral intravenous catheters in adults admitted to hospital in the Western Brazilian Amazon. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2016, 50, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Muñoz, R.; Marín-Navarro, L.; Gallego-Sánchez, J.C. Cuidados de Enfermería en los Accesos Vasculares. Guía De recomendaciones. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz. Área de Salud de Badajoz. 2018. Available online: https://www.areasaludbadajoz.com/Calidad_y_Seguridad_2016/Cuidados_enfermeria_accesos_vasculares.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Tork-Torabi, M.; Namnabati, M.; Allameh, Z.; Talakoub, S. Vancomycin Infusion Methods on Phlebitis Prevention in Children. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2019, 24, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gil, B.; Fernández-Castro, M.; López-Vallecillo, M.; Peña-García, I. Efectividad del tratamiento tópico de la flebitis secundaria a la cateterización periférica: Una revisión sistemática. Enferm. Glob. 2017, 16, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ortega, C.; Suárez Mier, B.; Cantero, M.; Llinás, M.; Plan Nacional Resistencia Antibióticos. Prevención de Complicaciones Relacionadas con Accesos Vasculares de Inserción Periférica. Programa Flebitis Zero. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. 2019. Available online: http://www.resistenciaantibioticos.es/es/system/files/content_images/programa_flebitis_zero.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Ray-Barruel, G.; Cooke, M.; Mitchell, M.; Chopra, V.; Rickrad, C.M. Implementing the I-DECIDED clinical decision-making tool for peripheral intravenous catheter assessment and safe removal: Protocol for an interrupted time-series study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infusion Nurses Society. Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice. J. Infus. Nurs. 2016, 36, 1–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz del Río, C.A.; Pérez de la Blanca, E.B.; Buzón Barrera, M.L.; Calderón Sandubete, E.; Carrero Caballero, M.C.; Carrión Camacho, M.R.; Luna Rodríguez, M.E.d.; García Aguilar, R.; García Díez, R.; García Fernández, F.P.; et al. Guía de Práctica Clínica Sobre Terapia Intravenosa con Dispositivos no Permanentes en Adultos. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Agencia de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias de Andalucía (AETSA). 2014. Available online: https://www.aetsa.org/publicacion/guia-de-practica-clinica-sobre-terapia-intravenosa-con-dispositivos-no-permanentes-en-adultos/ (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Nickel, B. Peripheral Intravenous Access: Applying Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice to Improve Patient Safety. Crit. Care Nurse 2019, 39, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, S.; Sen, S.; Cukurlu, D. Phlebitis-related peripheral venous catheterization and the associated risk factors. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbali-Babadi, M.; Ghadiriyan, R.; Hosseini, S.M. The effect of saline lock on phlebitis rates of patients in cardiac care units. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2015, 20, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milutinović, D.; Simin, D.; Zec, D. Risk factor for phlebitis: A questionnaire study of nurses’ perception. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2015, 23, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, M.S.; Costa-Lima, A.F. Direct cost of procedures for phlebitis treatment in an Inpatient Unit. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2020, 54, e03647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P.C.; Lee, Y.H.; Hsu, H.T.; Fneg, Y.T.; Lu, I.C.; Chiu, S.L.; Cheng, K.I. Establish a perioperative check forum for peripheral intravenous access to prevent the occurrence of phlebitis. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2015, 31, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, C.; Khadka, M.; Wosti, D.; Gurung, G.; Zhao, Q. Knowledge and practice towards care and maintenance of peripheral intravenous cannula among nurses in Chitwan Medical College Teaching Hospital, Nepal. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. Orden Cin/2134/2008, de 3 de Julio, Por la Que se Establecen los Requisitos para la Verificación de los Títulos Universitarios Oficiales que Habiliten para el Ejercicio de la Profesión de Enfermero. BOE Num 174, de 19 de Julio de 2008. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/2008/07/03/cin2134 (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Herdman, T.H.; Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.) NANDA International Nursing Diagnoses: Definition and Clasification 2018–2020, 11th ed.; Thieme Medical Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, H.K.; Bulechek, G.M.; Dochrterman, J.M.; Wagner, C. Clasificación de Intervenciones de Enfermería (NIC), 7th ed.; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-Olmo, R. Programa de habilidades en Lectura Crítica Español (CASPe). Nefroplus 2017, 9, 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Berra, S.; Elorza-Ricart, J.M.; Estrada, M.D.; Sánchez, E. Instrumento para la lectura crítica y la evaluación de estudios epidemiológicos transversales. Gac. Sanit. 2008, 22, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Gómez, I.D.; Montoya, D.C. Las guías de práctica clínica y el instrumento AGREE II. Rev. Colomb. Ppsiquiat. 2011, 40, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C.; Asenjo-Lobos, C.; Otzen, T. Jerarquización de la evidencia: Niveles de evidencia y grados de recomendación de uso actual. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2014, 31, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, Z.; Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E. The update Joanna Briggs Institute Model of Evidence Based Healthcare. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2019, 17, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichembach-Danski, M.T.; Mingorance, P.; Athanasio-Johann, D.; Adami-Vayego, S.; Lind, J. Incidence of local complications and risk factors associated with peripheral intravenous catheter in neonates. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2016, 50, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, L.M.; Parreira, P.M.; Salgueiro-Oliveira, A.S.; Mendes-Mónico, L.S.; Arreguy-Sena, C.; Henriques, M.A. Flebitis e infiltración: Traumas vasculares asociados al catéter venoso periférico. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 2018, 26, e3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário-Pereira, M.S.; de Oliveria-Cunha, A.T.; Almeida-Lima, E.F.; Ferreira-Santos, T.F.; Batista-Portugal, F. La Seguridad del paciente en el contexto de las flebitis notificadas en un hospital universitario. Rev. Epidemiol. Controle Infecção 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.Y.P.; Wong, C.Y.W.; Kek, L.K.; Suhairi, S.S.B.M.; Yip, W.K. Improving the Visibility of Intravenous (IV) Site in Pediatric Patients to Reduce IV Site Related Complications-An Evidence-based Utilization Project. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 41, e39–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugden, S.; Shean, K.; Scott, M.; Mihala, G.; Clark, S.; Johnstone, C.; Fraser, J.F.; Rickard, C.M. Skin Glue Reduces the Failure Rate of Emergency Department-Inserted Peripheral Intravenous Catheters: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2016, 68, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükyılmaz, F.; Şahiner, N.C.; Cağlar, S.; Eren, H. Effectiveness of an Intravenous Protection Device in Pediatric Patients on Catheter Dwell Time and Phlebitis Score. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annisa, F.; Nurhaeni, N.; Wanda, D. Warm Water Compress as an Alternative for Decreasing the Degree of Phlebitis. Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2017, 40 (Suppl. 1), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamloo, M.B.B.; Nasiri, M.; Maneiy, M.; Dorchin, M.; Mojab, F.; Bahrami, H.; Naseri, M.S.; Kiarsi, M. Effects of topical sesame (Sesamum indicum) oil on the pain severity of chemotherapy-induced phlebitis in patients with colorectal cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 35, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Ardani, M.; Yekefallah, L.; Asefzadeh, S.; Nassiri-Asl, M. Efficacy of topical chamomile on the incidence of phlebitis due to an amiodarone infusion in coronary care patients: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 15, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quintanilla, L.; Otero-Barreiro, M.; González-Barcia, M.; Virgós-Lamela, A.; Rodríguez-Prada, M.; Lamas, M.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A. Estudio de la Utilización, Eficacia y Seguridad de la Solución de Burow en el tratamiento de la flebitis. Rev. Ofil Ibero Lat. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2018, 28, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Jourabloo, N.; Nasrabadi, T.; Ebrahimi-Abyaneh, E. Comparing the effect of warm moist compress and Calendula ointment on the severity of phlebitis caused by 50% dextrose infusion: A clinical trial. Med. Surg. Nurs. 2017, 6, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Parreira, P.; Sousa, L.B.; Marques, I.A.; Santos-Costa, P.; Braga, L.M.; Cruz, A.; Salgueiro-Oliveira, A. Double-chamber syringe versus classic syringes for peripheral intravenous drug administration and catheter flushing: A study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2020, 21, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granda, M.J.; Bouza, E.; Pinilla, B.; Cruces, R.; González, A.; Millán, J.; Guembe, M. Randomized clinical trial analyzing maintenance of peripheral venous catheters in an internal medicine unit: Heparin vs. saline. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgingson, R. IV cannula securement: Protecting the patient from infection. Br. J. Nurs. 2015, 24, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, J.; Pellowe, C.; Instituto Joanna Briggs. Manejo de los dispositivos intravasculares periféricos. Best Pract. 2008, 12, 1–4, ISSN 1329-1874. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva-Oliveira, E.C.; Barros-de Oliveira, A.P.; de Oliveira, R.C. Caracterización de flebitis notificada a la gestión de riesgos en la red centinela hospitalaria. Rev. Baiana Enferm. 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattox, E.A. Complications of Peripheral Venous Access Devices: Prevention, Detection, and Recovery Strategies. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Osborne, S.; Rickard, C.M.; Marsh, N. Clinically-indicated replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous catheters. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 23, CD007798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilton, L.; Seymour, A.; Baker, R.B. Changing Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Sites When Clinically Indicated: An Evidence-Based Practice Journey. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2019, 16, 418–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oragano, C.A.; Patton, D.; Moore, Z. Phlebitis in Intravenous Amiodarone Administration: Incidence and Contributing Factors. Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parreira, P.; Serambeque, B.; Costa, P.S.; Mónico, L.S.; Oliveira, V.; Sousa, L.B.; Gama, F.; Bernardes, R.A.; Adriano, D.; Marques, I.A.; et al. Impact of an Innovative Securement Dressing and Tourniquet in Peripheral Intravenous Catheter-Related Complications and Contamination: An Interventional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Raghu, K. Study on incidence of phlebitis following the use of peripheral intravenous catheter. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 2827–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Nicolás, F.; Nazco-Casariego, G.J.; Viña-Romero, M.M.; González-García, J.; Ramos-Diaz, R.; Perez-Perez, J.A. Reducing the degree of colonisation of venous access catheters by continuous passive disinfection. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2016, 23, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, A.; Ullman, A.J.; Mihala, G.; Ray-Barruel, G.; Ray-Barruel, G.; Alexandrou, E.; Rickard, C.M. Peripheral intravenous catheter dressing and securement practice is associated with site complications and suboptimal dressing integrity: A secondary analysis of 40,637 catheters. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos-Alves, J.; Mendes-Rodrígues, C.; Velloso-Antunes, A. Prevalence of Phlebitis in a Clinical Inpatient Unit of a High-complexity Brazilian University Hospital. Rev. Bras. Ciências Saúde 2018, 22, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Ros, A.C.; Ramos-Oliveira, D.; Debon, R.; Scaratti, M. Intravenous therapy in hospitalized older adults: Care evaluation. Cogitare Enferm 2017, 2, e49989. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.S. A Model of Phlebitis Associated with Peripheral Intravenous Catheters in Orthopedic Inpatients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro-Buzatto, L.; Pinna-Massa, G.; Sorgini-Peterlini, M.A.; Yamaguchi-Whitaker, I. Factors associated with phlebitis in elderly patients with intravenous infusion. Acta. Paul. Enferm. 2016, 29, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Li, X.; Yue, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Lin, Q.; Tan, Y.; Peng, S.; Li, X. Catheter Dwell Time and Risk of Catheter Failure in Adult Patients With Peripheral Venous Catheters. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4488–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanetto, J.S.; Minuto-Muniz, F.O.; Martis da Silva, R.; Christo de Freitas, A.P.; Ribeiro de Oliveira, A.P.; Ramos dos Santos, J.C. Incidence of phlebitis and post-infusion phlebitis in hospitalised adults. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2017, 38, e58793. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, L.M.; Salgueiro-Oliveira, A.S.; Pereira Henriques, M.A.; Arreguy-Sena, C.; Pianetti Albergaria, V.M.; Dinis-Parreira, P.M. Cateterismo venoso periférico: Comprensión y evaluación de las prácticas de enfermería. Texto Context-Enferm. 2019, 28, e20180018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichembach Danski, M.T.; Johann, D.A.; Vayego, S.A.; Rodrigues-Lemes de Oliveira, G.; Lind, J. Complications related to the use of peripheral venous catheters: A randomized clinical trial. Acta. Paul. Enferm. 2016, 29, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Barruel, G. Infection Prevention: Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Assessment and Care. Aust. Nurs. Midwifery J. 2017, 24, 34. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).