1. Introduction

Since the discovery of chlorpromazine in France in the 1950s [

1], antipsychotic drugs (APs) have aimed to relieve disorganized thoughts and behaviors, hallucinations, and delusions. Accordingly, they are used to treat schizophrenia, bipolar mania, and behavioral symptoms, inter alia. The common mechanism underlying the efficacy of most APs is considered to be the antagonism of brain dopamine D2 receptors [

2]. In contrast with older drugs, referred to as ‘typical (or first-generation) antipsychotics’ (TAPs), the more recent ones (‘atypical (or second-generation) antipsychotics’, AAPs) are characterized by a stronger binding affinity to the serotonin 5HT2 receptor, compared to dopamine D2 receptors [

3].

In child psychiatry, despite limited evidence regarding their efficacy and safety profiles, APs are increasingly subject to off-label use [

4,

5,

6]. This phenomenon stems from a global increase in the prescribing of APs [

7,

8], a restricted pattern of marketing authorizations, as well as the lack of guidelines for their use in this population [

9,

10]. Aside from drug tolerance (which frequently leads to an increase in dosage), patients treated with APs are at risk of drug dependency [

11,

12,

13]. Whether resulting from prescription or recreative purposes (such as seeking euphoria or relaxation), this consumption may lead to abuse, intentional misuse, but also withdrawal phenomena [

14,

15]. In younger populations, ‘pharming’, which involves the non-medical use and misuse of, mainly psychoactive, medication [

16], may be favored in the growing role of the Internet and social media, especially regarding the easier accessibility of drugs [

17,

18]. Accordingly, the ‘psychonauts’ [

14,

16], ‘pharming’ users that try various psychoactive drugs and then share their experiences on social media, appeal to an ever-expanding audience, potentially influencing children and adolescents.

Studies investigating addictology-related symptoms in young people being scarce, beyond reports of accidental overdosage, we tried to characterize the different patterns of antipsychotic misuse and withdrawal, relying on an analysis of the World Health Organization (WHO) safety database (VigiBase

®, Uppsala Monitoring Centre, Sweden) [

19]. While withdrawal cases in infants and abuse cases in adolescents might be expected, there is still a grey area regarding middle-aged children. As antipsychotics are more and more subject to off-label use and illicit consumption in children and youth, we also aimed to identify potential drug safety signals regarding antipsychotic-related abuse, dependence, and withdrawal in this population. Further, we tried to shed some light on the most involved drugs, while suspecting the existence of different consumption patterns for each one, depending on the age group.

3. Results

3.1. Drug Abuse, Dependence, and Withdrawal

As of 4 August 2022, 16,054 reports belonging to the narrow SMQ ‘Drug abuse, dependence and withdrawal’ and involving consumers of antipsychotics were collected in VigiBase

® (UMC, Sweden). Among these reports, 1023 (6.4%) involved patients below 18 years of age, mostly belonging to the 12-to-17-year group (732, 71.6%). Records with patients aged under 18 mostly originated from the United States (398, 38.9%). Healthcare professionals issued 84.8% of the cases, with a majority of physicians (617, 60.3%). Details regarding the characteristics of the reports are provided in

Table 1.

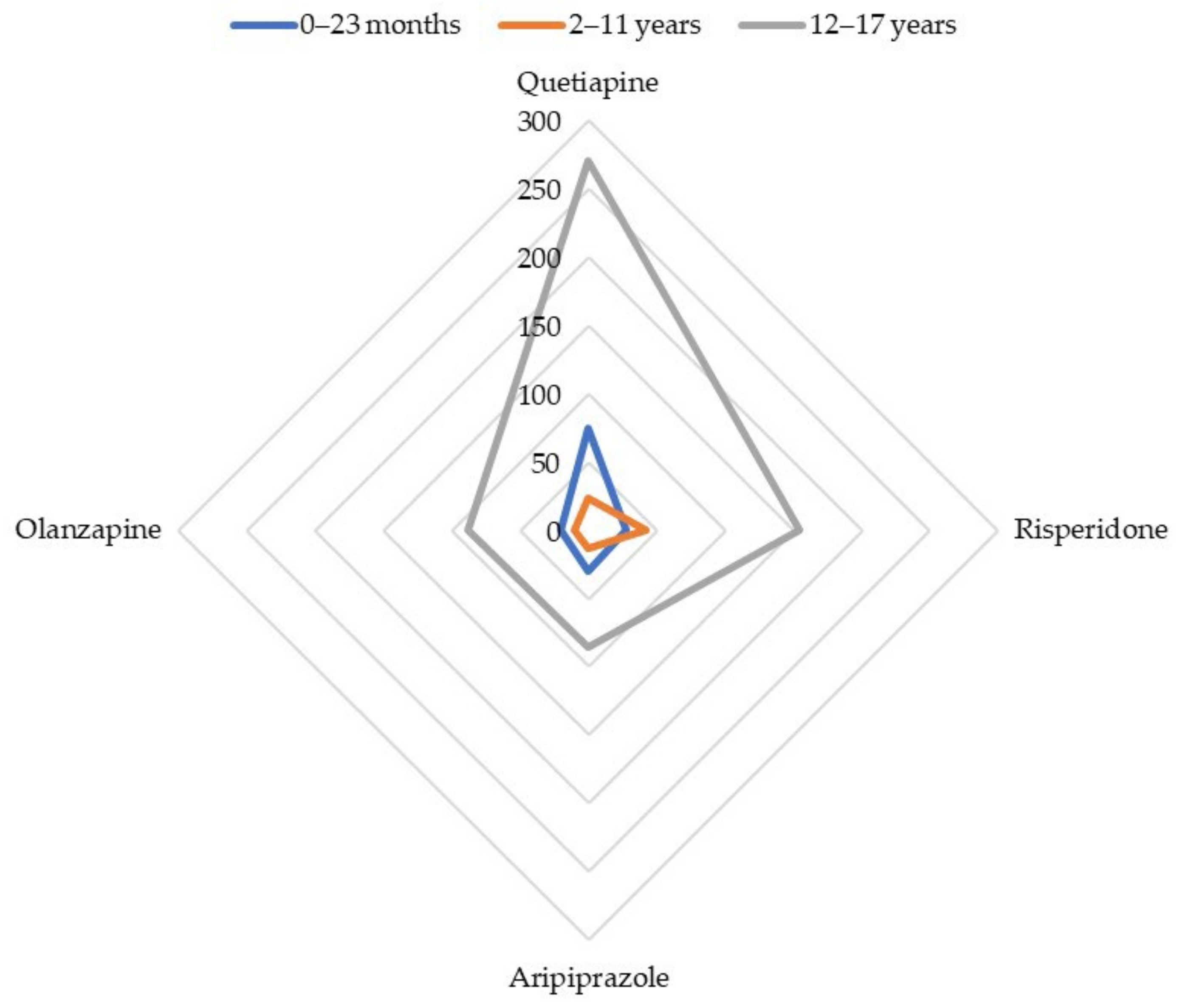

Four antipsychotics accounted for 839 (82.0%) reports of abuse, dependence, and withdrawal: quetiapine (368, 36.0%), risperidone (224, 21.9%), aripiprazole (129, 12.6%), and olanzapine (118, 11.5%). The number of reports for all ADRs in patients aged under 18 involving each of these antipsychotics is displayed in

Table S1.

Seriousness was assessed in 925 (90.4%) reports: 846 (91.5%) were deemed serious, among which 488 (57.6%) ADRs caused/prolonged hospitalizations, 78 (9.2%) life-threatening reactions, 40 (4.7%) deaths, and 30 (3.5%) congenital anomalies/birth defects. When details regarding the outcome were available (429, 41.6%), 356 (83.0%) patients recovered or were recovering, 40 (9.3%) did not recover, and 6 (1.4%) recovered with sequelae.

In patients aged under 18, antipsychotics were subject to a disproportionate reporting for the SMQ ‘Drug abuse, dependence and withdrawal’ (ROR 5.5; IC025 2.2).

3.2. Patients Aged between 0 Days and 23 Months

Among patients below 18 years of age, 198 (19.4%) reports of ADRs related to antipsychotic abuse, dependence, and withdrawal and involving infants aged from 0 days to 23 months were found in VigiBase

® (UMC, Sweden) In this age group, males represented 51.5% (n = 102) and their mean age was 2.3 (±2.9) months. Most of them (146, 73.7%) were newborns (aged under 28 days). The most frequently co-reported MedDRA terms were fetal exposure during pregnancy (63, 31.8%), premature baby (27, 12.1%), and tremor (17, 8.6%). Quetiapine was suspected in 75 records (37.8%), followed by aripiprazole (30, 15.2%), risperidone (28, 14.1%), and olanzapine (20, 10.1%). The complete list of involved antipsychotics is provided in

Table S2.

Co-reported drugs were found in 177 cases (89.4%). The most frequently suspected co-reported active ingredients were other psychotropic drugs, such as antidepressants sertraline (20, 10.1%), clomipramine and fluoxetine (18 cases each, 9.1%), venlafaxine (17, 8.6%), and the hypnotic drug zopiclone (14, 7.1%).

When available, 140 (96.5%) reports were deemed serious, among which 89 (63.6%) ADRs caused/prolonged hospitalizations, 30 (21.4%) congenital anomalies/birth defects, 13 (9.3%) life-threatening reactions, and 1 (0.7%) death. Among reports with available follow-up, 145 (91.8%) infants recovered or were recovering, 10 (6.3%) were not recovering, and 2 (1.3%) recovered with sequelae.

The most often involved antipsychotics (absolute number of reports) were disproportionately reported with the SMQ ‘Drug abuse, dependence, and withdrawal’: quetiapine (ROR 68.3; 95% CI: 53.2–87.8), risperidone (ROR 35.2; 95% CI: 23.8–52.0), aripiprazole (ROR 25.1; 95% CI: 17.2–36.4), and olanzapine (ROR 23.4; 95% CI: 14.9–36.9). Apart from quetiapine, the highest RORs were reached by cyamemazine (ROR 82.1; 95% CI: 47.5–141.8), amisulpride (ROR 68.3; 95% CI: 23.3–200.1), zuclopenthixol (ROR 60.3; 95% CI: 17.6–205.8), and levomepromazine (ROR 58.2; 95% CI: 28.6–118.0). The whole disproportionality analysis for cases of infants aged between 0 and 23 months is displayed in

Table 2.

Figure 1 summarizes the disproportionality analysis for the main antipsychotics involved in reports of abuse, dependence, or withdrawal, depending on the age range.

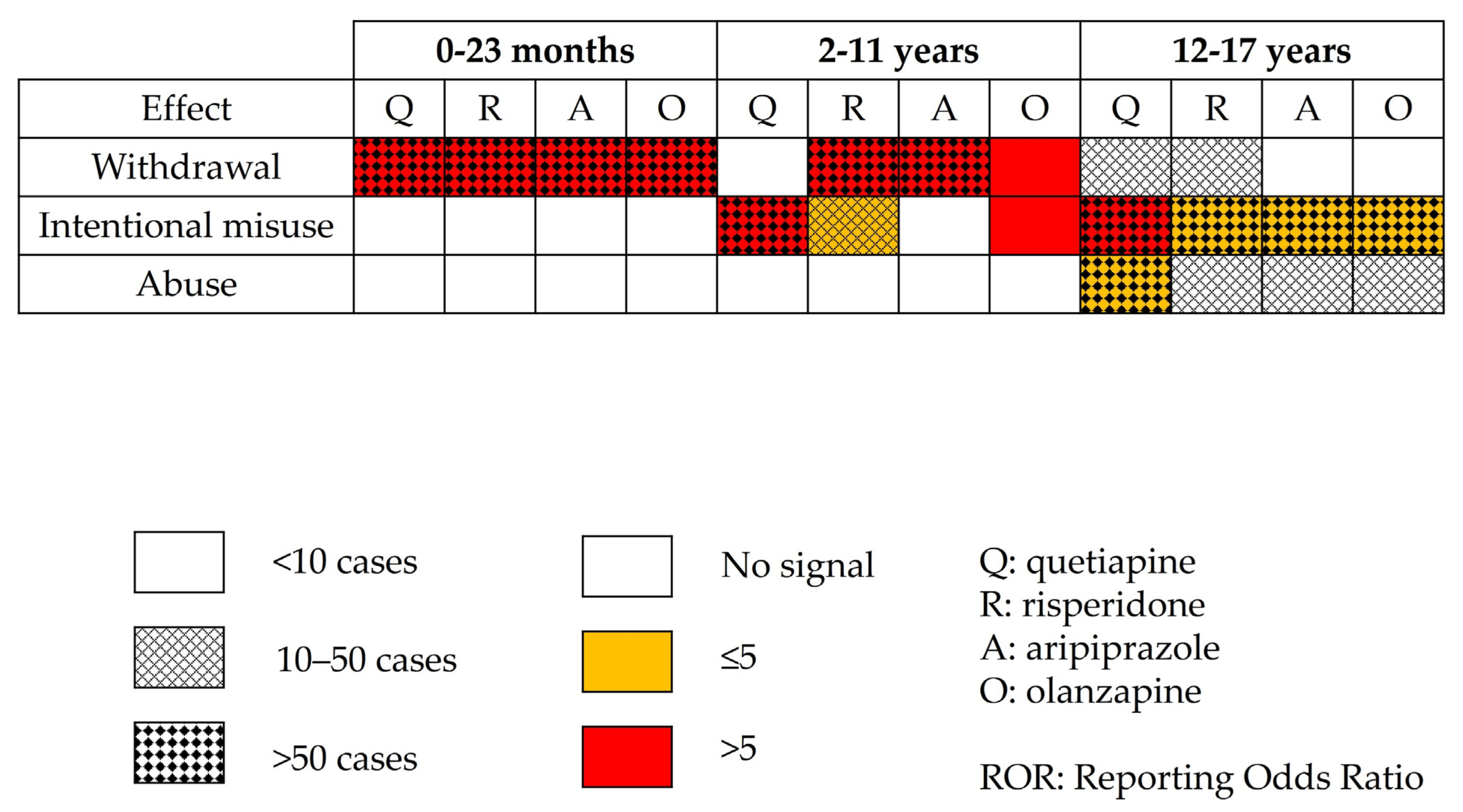

Upon closer inspection, in the narrow SMQ ‘Drug abuse, dependence, and withdrawal’, most reports involving infants aged between 0 days and 23 months referred to PTs related to withdrawal (192, 96.7%), as displayed in

Figure 2 and

Table S3.

The combination of ‘withdrawal’ PTs (drug withdrawal headache, drug withdrawal syndrome, drug withdrawal syndrome neonatal) showed disproportionate reporting for quetiapine (ROR 86.8; 95% CI: 67.4–111.8), risperidone (ROR 43.3; 95% CI: 29.1–64.5), aripiprazole (ROR 28.7; 95% CI: 19.4–42.5), and olanzapine (ROR 28.4; 95% CI: 17.8–45.3), as shown in

Table 3.

3.3. Patients Aged between 2 and 11 Years

Children aged between 2 and 11 years accounted for 93 (9.1%) reports involving patients aged under 18 years. The majority of patients in this age group were male (65, 69.9%), with a mean age of 8.4 years (±2.2). Dyskinesia (16, 17.2%), dystonia (13, 14.0%), and aggression (11, 11.8%) were the most frequently co-reported MedDRA terms. In this age range, risperidone was the most frequently suspected antipsychotic (42, 45.2%), followed by quetiapine (23, 24.7%), aripiprazole 13 (13, 14.0%), and olanzapine (10, 10.8%). The complete list is available in

Table S4.

Co-reported drugs were found in 63 cases (67.7%). The most frequently suspected co-reported active ingredients were methylphenidate (10, 10.8%), levothyroxine (6, 6.5%), citalopram (6, 6.5%), valproic acid (5, 5.4%), and omeprazole (5, 5.4%).

When available, 61 cases (79.2%) were considered to be serious, with 36 (46.8%) causing/prolonging hospitalizations, 8 (10.4%) deaths, and 4 (5.2%) life-threatening reactions. Among reports with follow-up, 19 (63.3%) infants recovered or were recovering, 4 (13.3%) were not recovering, and 2 (6.7%) recovered with sequelae.

Quetiapine (ROR 19.3; 95% CI: 12.7–29.4), olanzapine (ROR 10.0; 95% CI: 5.3–18.7), risperidone (ROR 5.0; 95% CI: 3.7–6.3), and aripiprazole (ROR 3.1; 95% CI: 1.8–5.3) were subject to a disproportionate reporting with the SMQ ‘Drug abuse, dependence, and withdrawal’ (

Table 4,

Figure 1).

In the SMQ ‘Drug abuse, dependence and withdrawal’, most reports involving children aged between 2 and 11 years referred to PTs related to intentional misuse (46, 49.5%) and withdrawal (37, 39.8%) (

Figure 2,

Table S5).

The ‘intentional misuse’ combination of PTs (intentional overdose, intentional product misuse) showed disproportionate reporting for quetiapine (ROR 34.4; 95% CI: 22.0–54.0), followed by olanzapine (ROR 12.2; 95% CI: 5.4–27.2) and risperidone (ROR 4.3; 95% CI: 2.7–6.9) (

Table 5). No report was found for aripiprazole in this category. The median time to onset for intentional misuse-related ADRs was 730 days (IQR 122–1460).

The ‘withdrawal’ combination of PTs (drug withdrawal syndrome, drug withdrawal convulsions) was subject to disproportionate reporting for olanzapine (ROR 13.7; 95% CI: 5.1–36.7), aripiprazole (ROR 10.0; 95% CI: 5.6–17.7), and risperidone (ROR 7.8; 95% CI: 4.9–12.4) (

Table 6).

3.4. Patients Aged between 12 and 17 Years

Adolescents aged between 12 and 17 years accounted for 732 (71.6%) of the queried reports. In this age group, most patients were female (408, 55.7%) and their mean age was 15.3 (±1.5) years, with more than one-quarter being 17-year-old adolescents (199, 27.2%). The most frequently co-reported MedDRA terms were suicide attempt (226, 30.9%), somnolence (156, 21.3%), and tachycardia (62, 8.5%). Quetiapine accounted for 270 records (36.9%), followed by risperidone (154, 21.0%), olanzapine (88, 12.0%), and aripiprazole (86, 11.7%). The complete list of suspected antipsychotics for this age range is available in

Table S6.

Other drugs were co-reported in 537 cases (73.4%). Fluoxetine (54, 7.4%), alprazolam (39, 5.3%), sertraline (36, 4.9%), paracetamol (35, 4.8%), and diazepam (28, 3.8%) were the most frequently suspected co-reported active ingredients.

When this information was available, 645 (61.7%) reports were deemed serious, including 363 (51.6%) causing/prolonging hospitalizations, 61 (8.6%) life-threatening reactions, and 31 (4.4%) deaths. Among reports with follow-up, 192 (76.7%) infants recovered or were recovering, 26 (10.7%) were not recovering, and 2 (0.8%) recovered with sequelae.

The most frequently involved antipsychotics were disproportionately reported with the narrow SMQ ‘Drug abuse, dependence and withdrawal’: quetiapine (ROR 8.9; 95% CI: 7.8–10.1), olanzapine (ROR 2.8; 95% CI: 2.3–3.5), risperidone (ROR 1.8; 95% CI: 1.5–2.1), and aripiprazole (ROR 1.7; 95% CI: 1.4–2.1) (

Table 7,

Figure 1). Beyond quetiapine, promazine (ROR 97.5; 95% CI: 56.0–169.8), chlorprothixene (ROR 35.5; 95% CI: 22.1–57.3), pipamperone (ROR 14.6; 95% CI: 8.5–25.0), and cyamemazine (ROR 4.2; 95% CI: 2.6–6.6) showed the greatest RORs.

Most of these reports referred to PTs related to intentional misuse (545, 74.5%) and abuse (168, 23.0%), as displayed in

Figure 2 and

Table S7.

The ‘intentional misuse’ combination of PTs (intentional overdose, intentional product misuse) was subject to disproportionate reporting for quetiapine (ROR 10.7; 95% CI: 9.3–12.3), olanzapine (ROR 3.6; 95% CI: 2.8–4.6), risperidone (ROR 2.1; 95% CI: 1.7–2.5), and aripiprazole (ROR 1.9; 95% CI: 1.5–2.5) (

Table 8).

The ‘abuse’ combination of PTs (drug abuse, drug dependence, substance abuse, drug abuser, drug use disorder, substance abuser, substance dependence, substance use disorder) was only disproportionately reported for quetiapine (ROR 4.8; 95% CI: 3.7–6.3), (

Table 9).

4. Discussion

Our analysis of the WHO pharmacovigilance database brings to light varying profiles for abuse, dependence, and withdrawal related to antipsychotics. Indeed, in infants aged under 2 years, almost all ADRs were understandably related to withdrawal symptoms. In children aged between 2 and 11 years, intentional misuse was at the forefront, with fewer cases of withdrawal, frequently complicated by extrapyramidal symptoms. Lastly, adolescents aged from 12 to 17 years were subject to intentional misuse, but also to abuse issues.

In infants aged from 0 days to 23 months, withdrawal syndrome reflects prenatal maternal exposure to APs. AAPs (quetiapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine) prevailed, both in terms of absolute number of cases and disproportionality, which is consistent with existing literature regarding their respective safety profiles and prescribing trends during pregnancy [

30,

31]. However, their drug labels indicate a risk of withdrawal in exposed neonates and recommend avoiding these drugs during pregnancy, unless their use is an absolute necessity [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Quetiapine showed the strongest signal in this population. Indeed, in women previously stabilized with quetiapine, it often remains prescribed during pregnancy [

36,

37]. At birth, the newborn being severed from the maternal blood supply and quetiapine being rapidly dissociated from the D2 receptors [

38,

39], its abrupt discontinuation may lead to greater risks of withdrawal at birth [

40]. The frequent maternal cotreatment with antidepressants (e.g., mood disorders) that we observed may also reinforce withdrawal symptoms in infants [

40,

41,

42].

In children aged between 2 and 11 years, the age and gender distribution regarding treatment with antipsychotics in the literature concurs with our findings [

43,

44,

45]. Indeed, significant disproportionality was found for AAP only, subject to a dramatic increase in consumption in children, circumscribed by the rise of off-label use in this population [

43,

44,

46,

47]. Regarding risperidone, which is the leading drug in terms of absolute number of reports, both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have granted it marketing authorization in irritability occurring in patients with an autistic disorder from the age of 5 [

35,

48]. Aripiprazole is authorized by the FDA from the age of 6 [

34] in the same indication, but its use is only recommended from the age of 13 by the EMA (manic episodes of bipolar I disorder) [

49]. Lastly, marketing authorization for olanzapine and for quetiapine is granted by the FDA in acute mixed or manic episodes of bipolar I disorder from the age of 10 [

32,

33]. However, the EMA stated that their safety and efficacy in children under the age of 18 have not been established yet and, therefore, that they should not be used in this group until further data become available [

50,

51]. In more than one-quarter of the reports, abuse, dependence, or withdrawal occurred concomitantly with dystonia and/or dyskinesia. These effects may reflect either overdosing following intentional misuse or withdrawal syndrome [

52,

53], subsequent to dopamine receptor hypersensitivity, GABA insufficiency, or cellular degeneration (neurotoxicity) [

54,

55]. In cases of withdrawal, the strongest disproportionality signals concerned risperidone and aripiprazole. This may indicate abrupt treatment discontinuations that could be favored by the urge of appeasing irritability and/or aggressive symptoms via the initiation of a new medication (e.g., in patients suffering from autistic disorders). In addition, possible impulsive and voluntary intoxications may also occur, especially in children presenting with behavioral disorders.

Adolescents aged from 12 to 17 years accounted for the vast majority of the reports belonging to the SMQ ‘drug abuse, dependence and withdrawal’. Paracetamol was quite frequently co-reported as suspect or interacting, which may reflect the fact that suicide attempts accounted for nearly one-third of the reports in this age range [

56]. Further, ingestion of co-reported substances, such as antidepressants and benzodiazepines, might also concur with phenomena of intentional misuse or abuse or designate a population of patients receiving long-term treatment with psychotropic drugs. In this context, the AAPs quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and aripiprazole were subject to disproportionate reporting, to a greater degree than TAPs, such as promazine, chlorprothixene, and cyamemazine. Regarding TAPs, cyamemazine has been granted marketing authorization in France (Agence Nationale du Médicament et des produits de santé—ANSM) for behavioral disorders with psychomotor agitation and aggressivity for children aged 3 years or older [

57]. Promazine and chlorprothixene were withdrawn from the market in the United States [

58,

59]. However, commonly prescribed AAPs may be ingested for recreative purposes, as Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPSs) [

12,

18]. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), NPSs are ‘substances of abuse, either in a pure form or a preparation, that are not controlled by the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs or the 1961 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, but which may pose a public health threat’ [

60]. Compared to ‘conventional’ illicit substances, NPSs are distinguished by greater affordability and ease of online purchase, but also lower detectability and social stigma [

61]. In younger populations, both appeasement of other consumption symptoms and search of emotional anesthesia are becoming more and more accessible, as these phenomena are further exacerbated by the ‘pharming’ and ‘psychonauts’ trends. As abuse and intentional misuse have been described for risperidone and aripiprazole [

13,

62], we extend this potential signal to adolescent populations. In line with previous findings (irrespective of the age range) [

13,

15], olanzapine was disproportionately reported for intentional misuse. Olanzapine can be consumed as a psychedelic or for its sedative effect, with rewarding properties involving glutamatergic stimulation of dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area [

63]. Our findings confirm that quetiapine, already involved in pharmacovigilance signals of intentional misuse and abuse, raises also issues in adolescents. Indeed, it is the leading drug in terms of absolute number of reports. Quetiapine has multiple street names, such as ‘quell’, ‘Susie-Q’, ‘baby heroin’, and ‘Q-ball’ (when associated with cocaine) [

64]. Consumed for anxiolytic properties, its popularity as an NPS may be linked to H1 and α1 receptor antagonism. The same rationale may apply to olanzapine, more and more available on the black market [

13,

64,

65].

While other studies aimed to assess the importance of antipsychotic abuse and misuse in different pharmacovigilance databases [

13,

15,

66], our analysis was the first to focus on children and youth. It highlighted different profiles, depending on the age of the patients. Nevertheless, this study is hindered by the inherent flaws of spontaneous reporting systems and post-marketing pharmacovigilance approaches, such as incomplete data and reporting bias. The strict definitions of the terms, from a pharmacovigilance perspective, might be unclear for notifiers, which may have led to a substantial coding heterogeneity, especially regarding intentional misuse and abuse. However, most reports were notified by healthcare professionals, which limits the risk of coding errors. Further, lack of follow-up and under-reporting, although usual in pharmacovigilance [

67], may have been heightened by the extent of overall consumption and the acute nature of manifestations (especially related to withdrawal or intentional overdose). Then, associated medications were recorded (co-reported active ingredients), but we were not able to retrieve data on the consumption of other illegal substances, as this is outside the scope of VigiBase

®(UMC, Sweden) Lastly, pharmaco-epidemiological studies aim to raise awareness about possible drug safety signals and no definite causality can be drawn from our findings.

Regarding implications for practice and research, different areas have to be taken into account. During pregnancy, as recommended by the safety agencies [

32,

33,

34,

35,

48,

49,

50,

51], each antipsychotic treatment must be introduced or maintained following a careful assessment of the benefit/risk ratio. In children, off-label prescription should be properly substantiated, considering the scarcity of data regarding safety in efficacy in this population [

50,

51]. In adolescents, the risk of antipsychotic abuse and its characteristics should be further investigated. In addition, particular heed should be paid to specialized social networks, underlying new consumption patterns [

14,

16].