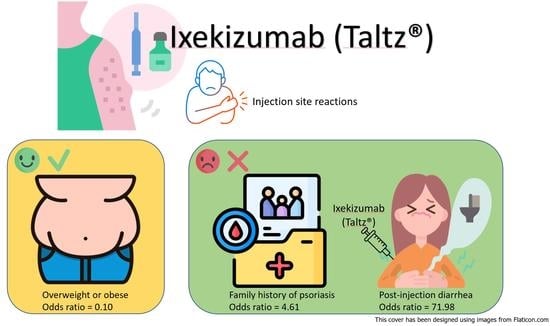

Risk Factors of Ixekizumab-Induced Injection Site Reactions in Patients with Psoriatic Diseases: Report from a Single Medical Center

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

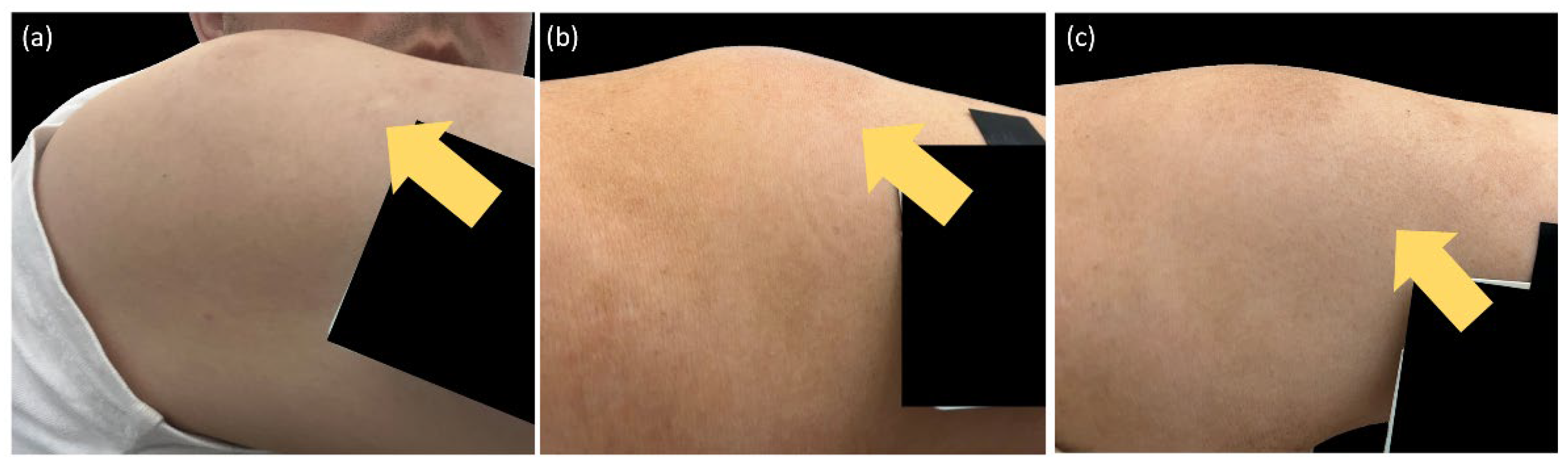

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parisi, R.; Iskandar, I.Y.K.; Kontopantelis, E.; Augustin, M.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Ashcroft, D.M. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: Systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ 2020, 369, m1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-S.; Chen, P.-H.; Hsu, S.-H.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Tsai, T.-F. Psoriasis in Taiwan: From epidemiology to new treatments. Dermatol. Sin. 2018, 36, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-F.; Ho, J.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Hsiao, P.-F.; Lee, W.-R.; Chi, C.-C.; Lan, C.-C.; Hui, R.C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Yang, K.-C.; et al. Health-related quality of life among patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in Taiwan. Dermatol. Sin. 2018, 36, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.S.; Kim, T.-H. The role of ixekizumab in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2021, 13, 1759720X20986734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.B.; Blauvelt, A.; Papp, K.A.; Langley, R.G.; Luger, T.; Ohtsuki, M.; Reich, K.; Amato, D.; Ball, S.G.; Braun, D.K.; et al. Phase 3 Trials of Ixekizumab in Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahnik, B.; Beroukhim, K.; Zhu, T.H.; Abrouk, M.; Nakamura, M.; Singh, R.; Lee, K.; Bhutani, T.; Koo, J. Ixekizumab for the Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review of Phase III Trials. Dermatol. Ther. 2016, 6, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, F.; Piaserico, S. The dark side of the moon: The immune-mediated adverse events of IL-17A/IL-17R inhibition. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eker, H.; Islamoğlu, Z.G.K.; Demirbaş, A. Vitiligo development in a patient with psoriasis vulgaris treated with ixekizumab. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marasca, C.; Fornaro, L.; Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Fabbrocini, G.; Megna, M. Onset of vitiligo in a psoriasis patient on ixekizumab. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e15102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loft, N.D.; Vaengebjerg, S.; Halling, A.-S.; Skov, L.; Egeberg, A. Adverse events with IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of phase III studies. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paller, A.S.; Seyger, M.M.; Magariños, G.A.; Pinter, A.; Cather, J.C.; Rodriguez-Capriles, C.; Zhu, D.; Somani, N.; Garrelts, A.; Papp, K.A.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of up to 108 weeks of ixekizumab in pediatric patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: The IXORA-PEDS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.K.; Shin, J.U.; Lee, H.J.; Yoon, M.S.; Kim, D.H. Injection site reactions due to the use of biologics in patients with psoriasis: A retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2023, 10, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shear, N.H.; Paul, C.; Blauvelt, A.; Gooderham, M.; Leonardi, C.; Reich, K.; Ohtsuki, M.; Pangallo, B.; Xu, W.; Ball, S.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of Ixekizumab: Integrated Analysis of Injection-Site Reactions from 11 Clinical Trials. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2018, 17, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomaidou, E.; Ramot, Y. Injection site reactions with the use of biological agents. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e12817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Barrios, M.; Rodriguez-Peralto, J.L.; Vico-Alonso, C.; Velasco-Tamariz, V.; Calleja-Algarra, A.; Ortiz-Romero, P.; Rivera-Diaz, R. Injection-site reaction to ixekizumab histologically mimicking lupus tumidus: Report of two cases. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2018, 84, 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poelman, S.M.; Keeling, C.P.; Metelitsa, A.I. Practical Guidelines for Managing Patients with Psoriasis on Biologics: An Update. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2019, 23 (Suppl. 1), 3S–12S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NicDhonncha, E.; Bennett, M.; Murphy, L.A.; Murphy, M.; Bourke, J.F. Injection site reactions to ixekizumab—A series of four patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, e137–e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.; Tsai, T. Clinical experience of ixekizumab in the treatment of patients with history of chronic erythrodermic psoriasis who failed secukinumab: A case series. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 181, 1106–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.-H.; Lee, J.J.; Yu, E.W.-R.; Hu, H.-Y.; Lin, S.-Y.; Ho, C.-Y. Association between obesity and education level among the elderly in Taipei, Taiwan between 2013 and 2015: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, K.; Puig, L.; Mallbris, L.; Zhang, L.; Osuntokun, O.; Leonardi, C. The effect of bodyweight on the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab: Results from an integrated database of three randomised, controlled Phase 3 studies of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, L.W.; Schiff, M.H.; Baumgartner, S.W.; Tindall, E.A.; Fleischmann, R.M.; Bulpitt, K.J.; Weaver, A.L.; Keystone, E.C.; Furst, D.E.; Mease, P.J.; et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Estebaranz, J.L.; Sánchez-Carazo, J.L.; Sulleiro, S. Effect of a family history of psoriasis and age on comorbidities and quality of life in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: Results from the ARIZONA study. J. Dermatol. 2015, 43, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, J.; Hu, J.Z.; Nowacki, A.S.; Khanna, U.; Mazloom, S.; Kabbur, G.; Husni, M.E.; Fernandez, A.P. Family history of psoriasis, psychological stressors, and tobacco use are associated with the development of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: A case-control study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.-H.; Sun, C.-C.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Chu, C.-Y. Contact dermatitis to topical medicaments: A retrospective study from a medical center in Taiwan. Dermatol. Sin. 2015, 33, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöhrl, S.; Hemmer, W.; Focke, M.; Götz, M.; Jarisch, R. Patch Testing in Children, Adults, and the Elderly: Influence of Age and Sex on Sensitization Patterns. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2003, 20, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caron, B.; Jouzeau, J.-Y.; Miossec, P.; Petitpain, N.; Gillet, P.; Netter, P.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Gastroenterological safety of IL-17 inhibitors: A systematic literature review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 21, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, N.-L.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Tsai, T.-F.; Chiu, H.-Y. Gut Microbiome in Psoriasis is Perturbed Differently During Secukinumab and Ustekinumab Therapy and Associated with Response to Treatment. Clin. Drug Investig. 2019, 39, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, I.; Ramser, A.; Isham, N.; Ghannoum, M.A. The Gut Microbiome as a Major Regulator of the Gut-Skin Axis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, C.E.M.; Gooderham, M.; Colombel, J.-F.; Terui, T.; Accioly, A.P.; Gallo, G.; Zhu, D.; Blauvelt, A. Safety of Ixekizumab in Adult Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis: Data from 17 Clinical Trials with Over 18,000 Patient-Years of Exposure. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 1431–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.M.; Madsen, S.; Krase, J.M.; Shi, V.Y. Classification and mitigation of negative injection experiences with biologic medications. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Lai, T.W. Citric Acid in Drug Formulations Causes Pain by Potentiating Acid-Sensing Ion Channel 1. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 4596–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, T.; Hansen, B.; Fisker, S. Pain Perception after Subcutaneous Injections of Media Containing Different Buffers. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006, 98, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.S.; Luu, P. 854 Comparison of Injection Site Pain with Citrate Free and Original Formulation Adalimumab in Pediatric IBD Patients. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2019, 114, S493–S494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabra, S.; Gill, B.J.; Gallo, G.; Zhu, D.; Pitou, C.; Payne, C.D.; Accioly, A.; Puig, L. Ixekizumab Citrate-Free Formulation: Results from Two Clinical Trials. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 2862–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics (N = 116) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (year, mean ± SD) | 51.2 | 13.0 |

| Gender (male) | 85 | 73.3% |

| Height (cm, mean ± SD) | 167.4 | 8.11 |

| Weight (kg, mean ± SD) | 78.1 | 16.2 |

| Onset age of PsO (year, mean ± SD) | 29.6 | 15.1 |

| FH of PsO | 38 | 32.8% |

| Habit | ||

| Smoking | 46 | 39.7% |

| Alcohol | 25 | 21.6% |

| BMI | ||

| Underweight | 0 | 0% |

| Normal | 24 | 20.7% |

| Overweight | 32 | 27.6% |

| Obesity | 60 | 51.7% |

| Baseline severity of PsO | ||

| PASI (mean ± SD) | 12.0 | 8.8 |

| BSA (mean ± SD) | 17.8 | 22.8 |

| Underlying diseases | ||

| Erythrodermic PsO | 18 | 15.6% |

| PsA | 74 | 63.8% |

| HTN | 49 | 42.2% |

| DM | 26 | 22.4% |

| CVD | 4 | 3.4% |

| HBV | 10 | 8.6% |

| IGRA | 21 | 18.1% |

| Prior PsO treatments | ||

| Acitretin | 82 | 70.7% |

| MTX | 95 | 81.9% |

| CsA | 29 | 25.0% |

| Phototherapy | 91 | 78.4% |

| Prior Biologic agents | 95 | 81.9% |

| 1 agent | 27 | 23.3% |

| 2 agents | 24 | 20.7% |

| 3 agents | 17 | 14.7% |

| 4 agents | 14 | 12.1% |

| 5 agents | 8 | 6.9% |

| 6 agents | 5 | 3.4% |

| 7 agents | 0 | 0% |

| 8 agents | 1 | 0.9% |

| Event Type (N = 116) | ||

|---|---|---|

| ISRs | ||

| Incidence | 40 | 34.5% |

| Duration (day, mean ± SD) | 2.6 | 1.1 |

| Diarrhea | ||

| Incidence | 19 | 16.4% |

| Duration (day, mean ± SD) | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| Severity of PsO at week 12 | ||

| PASI (mean ± SD) | 2.7 | 4.3 |

| BSA (mean ± SD) | 2.4 | 9.0 |

| PASI response at week 12 | ||

| PASI 75 | 81 | 69.8% |

| PASI 90 | 52 | 44.8% |

| PASI 100 | 35 | 30.2% |

| Characteristics | OR | (95.0% C.I.) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.95 | (0.92–0.98) | 0.002 |

| Height | 1.01 | (0.96–1.06) | 0.70 |

| Weight | 1.00 | (0.98–1.02) | 0.89 |

| Onset age of PsO | 0.96 | (0.93–0.99) | 0.003 |

| Gender (male) | 0.54 | (0.23–1.25) | 0.14 |

| Family history of PsO | 2.71 | (1.21–6.10) | 0.01 |

| Habit | |||

| Smoking | 0.87 | (0.40–1.91) | 0.73 |

| Alcohol | 0.87 | (0.34–2.23) | 0.77 |

| BMI ≥ 24 | 0.35 | (0.14–0.88) | 0.02 |

| Baseline PASI | 1.00 | (0.95–1.04) | 0.87 |

| Underlying diseases | |||

| Erythrodermic PsO | 1.25 | (0.45–3.53) | 0.67 |

| PsA | 1.08 | (0.49–2.41) | 0.84 |

| HTN | 0.74 | (0.34–1.62) | 0.45 |

| DM | 0.64 | (0.24–1.67) | 0.36 |

| CVD | 0.62 | (0.06–6.20) | 1.00 |

| HBV | 0.45 | (0.09–2.22) | 0.49 |

| IGRA | 0.54 | (0.18–1.59) | 0.26 |

| Prior PsO treatments | |||

| Acitretin | 1.69 | (0.70–4.08) | 0.24 |

| MTX | 1.39 | (0.50–3.93) | 0.53 |

| CsA | 1.81 | (0.76–4.27) | 0.18 |

| Phototherapy | 1.89 | (0.69–5.19) | 0.21 |

| Prior biologic agents | 1.28 | (0.45–3.63) | 0.64 |

| Diarrhea after injection | 7.65 | (2.51–23.33) | <0.001 |

| PASI response at week 12 | |||

| PASI 75 | 1.22 | (0.52–2.84) | 0.65 |

| PASI 90 | 1.18 | (0.55–2.54) | 0.68 |

| PASI 100 | 1.41 | (0.62–3.21) | 0.41 |

| Characteristics | OR | (95.0% C.I.) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.95 | (0.88–1.02) | 0.14 |

| Height | 1.08 | (0.94–1.25) | 0.27 |

| Weight | 0.98 | (0.92–1.04) | 0.48 |

| Onset age of PsO | 0.98 | (0.91–1.05) | 0.50 |

| Gender (male) | 0.14 | (0.01–1.40) | 0.09 |

| Family history of PsO | 4.61 | (1.25–17.09) | 0.02 |

| Habit | |||

| Smoking | 1.90 | (0.47–7.70) | 0.37 |

| Alcohol | 0.47 | (0.09–2.49) | 0.37 |

| BMI ≥ 24 | 0.10 | (0.01–0.74) | 0.02 |

| Baseline PASI | 1.01 | (0.92–1.10) | 0.89 |

| Underlying diseases | |||

| Erythrodermic PsO | 2.33 | (0.32–16.95) | 0.40 |

| PsA | 1.05 | (0.27–4.06) | 0.95 |

| HTN | 0.45 | (0.10–2.00) | 0.29 |

| DM | 2.00 | (0.32–12.40) | 0.46 |

| CVD | 1.35 | (0.07–25.47) | 0.84 |

| HBV | 0.16 | (0.01–2.34) | 0.18 |

| IGRA | 2.29 | (0.32–16.44) | 0.41 |

| Prior PsO treatments | |||

| Acitretin | 0.13 | (0.01–1.38) | 0.09 |

| MTX | 0.84 | (0.11–6.45) | 0.87 |

| CsA | 5.45 | (0.91–32.75) | 0.06 |

| Phototherapy | 6.78 | (0.65–71.21) | 0.11 |

| Prior biologic agents | 1.65 | (0.25–11.01) | 0.60 |

| Diarrhea after injection | 71.98 | (9.31–556.47) | <0.001 |

| PASI 75 at week 12 | 0.57 | (0.14–2.29) | 0.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiu, I.-H.; Tsai, T.-F. Risk Factors of Ixekizumab-Induced Injection Site Reactions in Patients with Psoriatic Diseases: Report from a Single Medical Center. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11061718

Chiu I-H, Tsai T-F. Risk Factors of Ixekizumab-Induced Injection Site Reactions in Patients with Psoriatic Diseases: Report from a Single Medical Center. Biomedicines. 2023; 11(6):1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11061718

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiu, I-Heng, and Tsen-Fang Tsai. 2023. "Risk Factors of Ixekizumab-Induced Injection Site Reactions in Patients with Psoriatic Diseases: Report from a Single Medical Center" Biomedicines 11, no. 6: 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11061718

APA StyleChiu, I.-H., & Tsai, T.-F. (2023). Risk Factors of Ixekizumab-Induced Injection Site Reactions in Patients with Psoriatic Diseases: Report from a Single Medical Center. Biomedicines, 11(6), 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11061718