Disseminated Peritoneal Leiomyomatosis—A Challenging Diagnosis-Mimicking Malignancy Scoping Review of the Last 14 Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

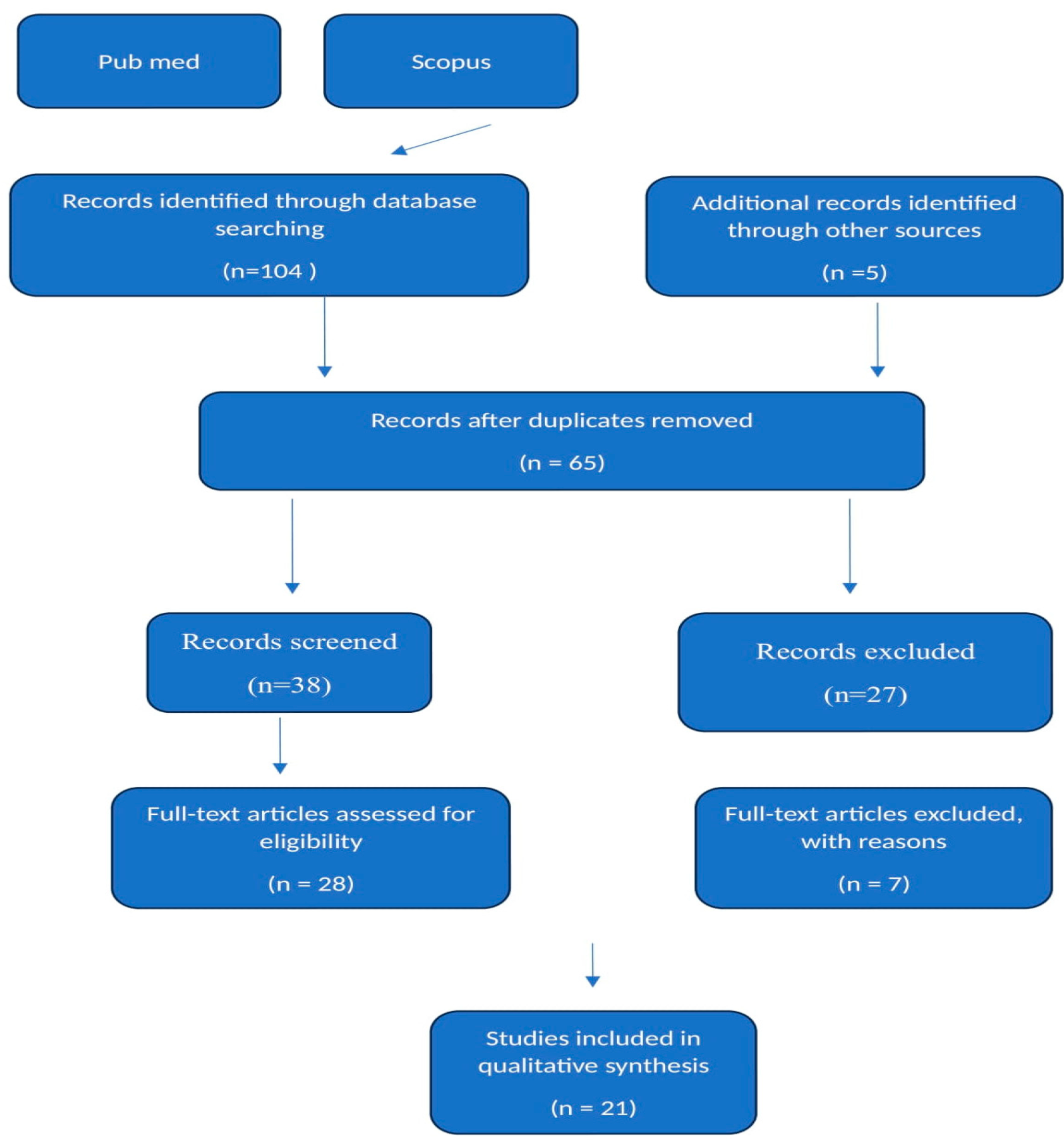

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Peritoneal Leiomyomatosis Pathogenesis, Epidemiology, Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating Uterine Leiomyomas from DPL

2.2. DPL Diagnosis

- ○

- Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma that typically presents with diffuse thickening of the peritoneum, which can be distinguished from DPL by its pattern and associated calcifications. Histopathology is crucial for differentiation, as mesothelioma shows a diffuse malignant cell pattern, unlike the well-circumscribed leiomyomas seen in DPL [1].

- ○

- Ovarian leiomyomatosis that typically manifests as localized ovarian masses rather than diffuse peritoneal lesions. Histologically, these are similar to uterine leiomyomas but confined to the ovaries [11].

- ○

- Sarcomas (including leiomyosarcomas) that exhibit more aggressive features, including high cellularity, atypical mitoses, and necrosis. Imaging may show irregular masses with heterogeneous enhancement [12].

- ○

- Other tumors such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) that are differentiated by immunohistochemical profiles (e.g., CD117 positive) and distinct cellular morphology.

3. Results

3.1. Gestation/Para

3.2. Age

3.3. Symptoms

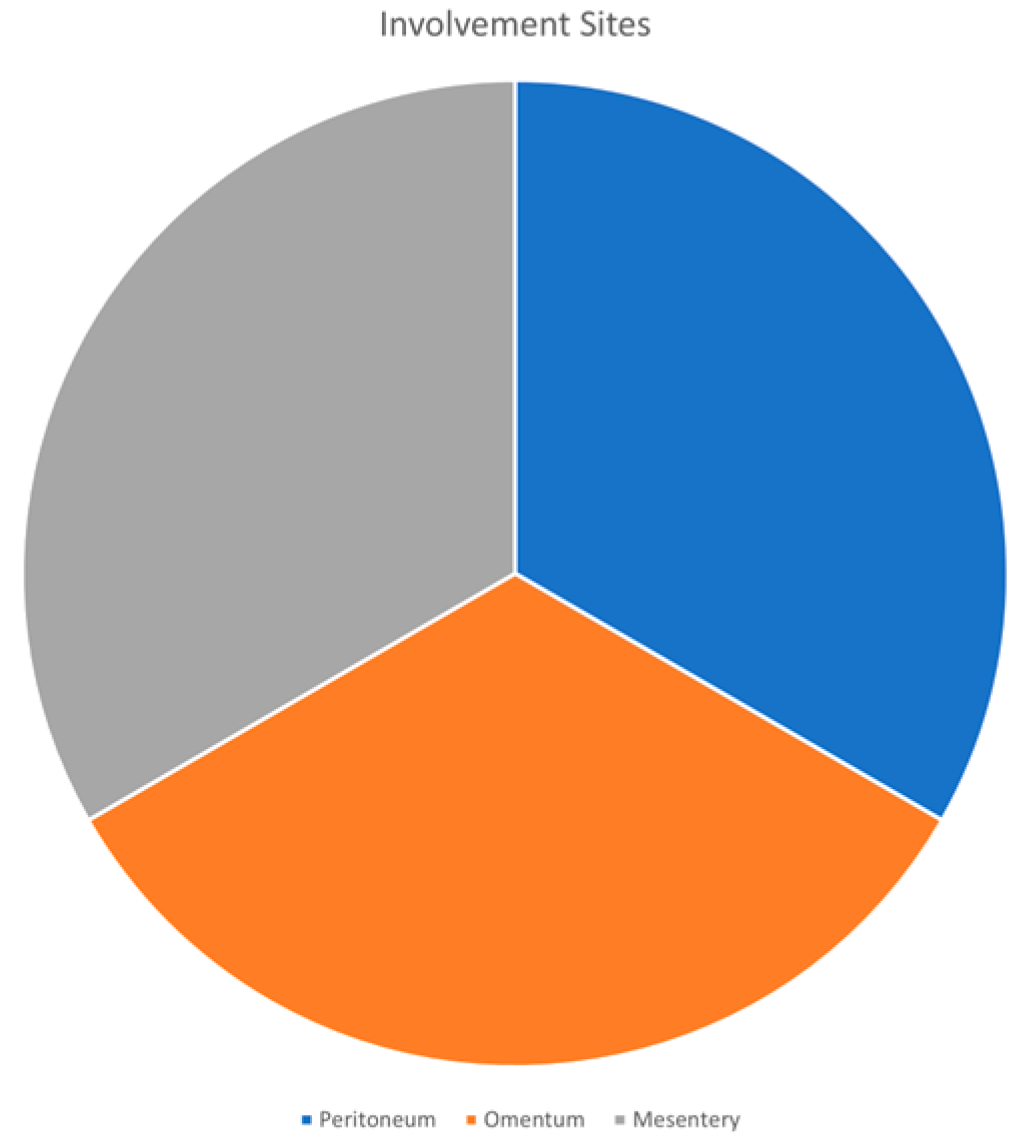

3.4. Involvement Sites

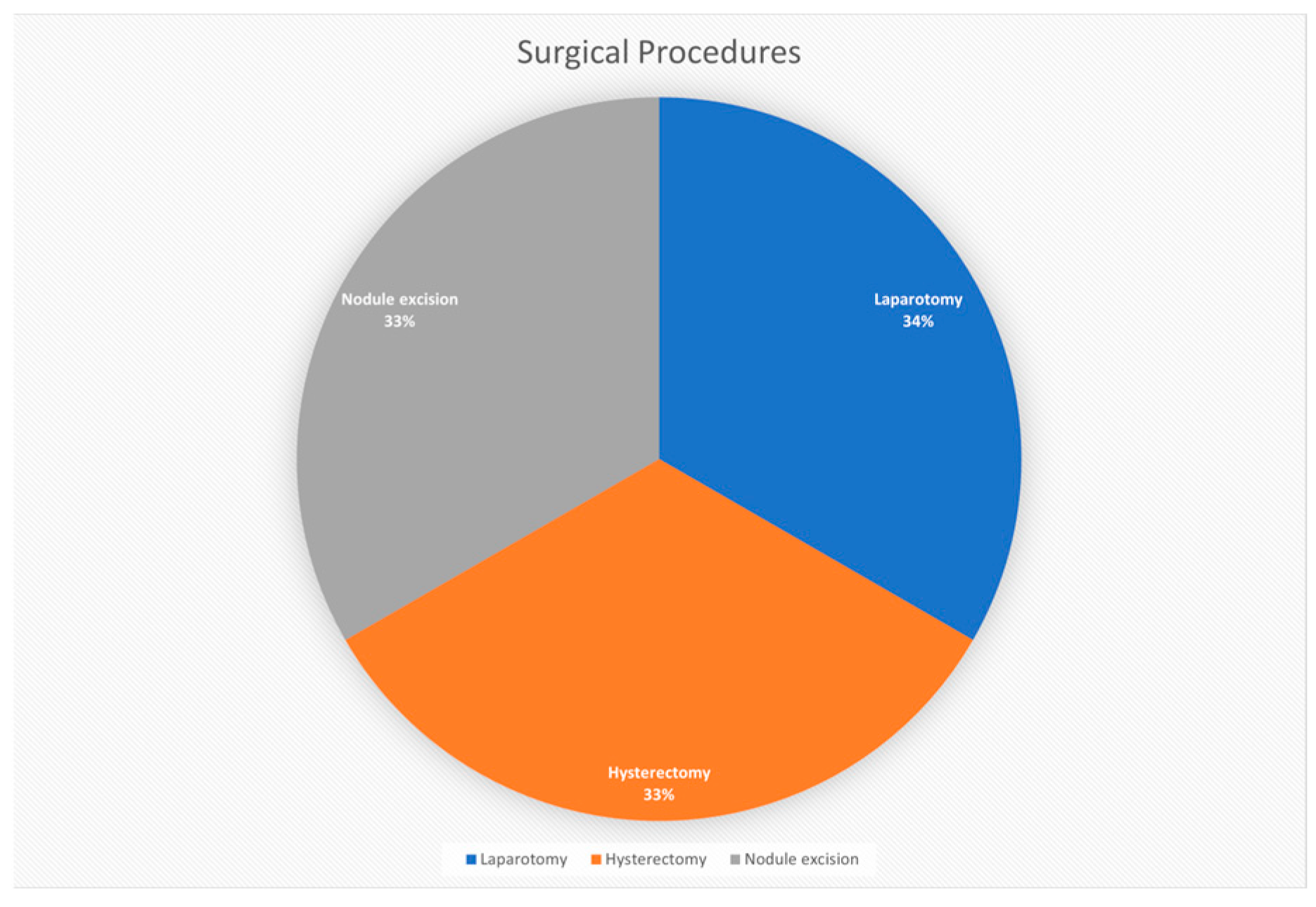

3.5. Surgical Procedures

3.5.1. Number of Nodules

3.5.2. Follow-Up Period

3.5.3. DPL Management

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soni, S.; Pareek, P.; Narayan, S. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis: An unusual presentation of intra-abdominal lesion mimicking disseminated malignancy. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2020, 93, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosati, A.; Vargiu, V.; Angelico, G.; Zannoni, G.F.; Ciccarone, F.; Scambia, G.; Fanfani, F. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis and malignant transformation: A case series in a single referral center. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 262, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Dai, S. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata: A clinical analysis of 13 cases and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 28, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.W.; Hua, Y.; Xu, H.; He, L.; Huo, H.Z.; Zhu, C.F. Treatment of leiomyomatosis peritoneal dissemination with goserelin acetate: A case report and review of the literature. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 5217–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.D.; Kahiye, M.; Kule, I.; Yahaya, J.J.; Othieno, E. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis as an incidental finding: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e05541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thi, S.N.; Thy, T.M.; Huy, H.P. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis: Two case reports and literature review. Pathology 2023, 55, S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, M.; Al-Hendy, A. Medical treatment of uterine leiomyoma. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 19, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izi, Z.; Outznit, M.; Cherraqi, A.; Tbouda, M.; Billah, N.M.; Nassar, I. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis: A case report. Radiol. Case Rep. 2023, 18, 2237–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnavi, R.; Nair, S.S.; Sudha, S.; Nitu, P. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis: An unusual complication of laparoscopic myomectomy. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2024, 18, QD04–QD05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Q. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis: A case report and review of the literature. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 03000605211033194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.F.; Wen, C.Y.; Liao, C.I.; Lin, J.C.; Tsai, C.C. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata mimicking peritoneal carcinomatosis 13 years after laparoscopic uterine myomectomy: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 81, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Qian, J. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata with sarcomatous transformation: A rare case report and literature review. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 2019, 3684282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, E.-J.; Chang, Y.-W.; Hong, S.-S.; Hwang, J.; Oh, E.; Num, B.D.; Choi, I.-H.; Lee, H.P. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis with atypical features and comorbid uterine STUMP: A case report and review of the literature. Investig. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 24, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, L.; Zerbi, P.; Angiolini, M.R.; Agarossi, A.; Riggio, E.; Bondurri, A.; Danelli, P. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata: A case report of recurrent presentation and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 49, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, A.S.; Angeles, M.A.; Illac, C.; Boulet, B.; Ferron, G.; Martinez, A. Effect of medical treatments in disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis: A case report. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 2022, rjac166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verguts, J.; Orye, G.; Marquette, S. Symptom relief of leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata with ulipristal acetate. Gynecol. Surg. 2014, 11, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mex, G.O. Leiomiomatosis peritoneal. Caso tratado mediante laparoscopia. Ginecol. Obstet. Mex. 2014, 82, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimercati, A.; Santarsiero, C.M.; Esposito, A.; Putino, C.; Malvasi, A.; Damiani, G.R.; Laganà, A.S.; Vitagliano, A.; Marinaccio, M.; Restra, L.; et al. A sporadic case of disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis with a pelvic leiomyosarcoma and omental metastasis after laparoscopic morcellation: A systematic review of the literature. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Shi, H.; Fan, Q.; Sun, D.; Lang, J. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata following laparoscopic surgery with uncontained morcellation: 13 cases from one institution. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 788749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, N.; Liu, Y. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata: Three case reports. Medicine 2020, 99, e22633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, Y.; Yoshiki, N.; Nakamura, R.; Iwahara, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Miyasaka, N. Large leiomyomatosis peritoneal dissemination after laparoscopic myomectomy: A case report with literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 77, 866–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Data |

|---|---|

| Gestation/para | Nullipara/1/2 |

| Average age | 38.5 years |

| Most common symptoms | Abdominal discomfort, pelvic pain |

| Frequent Involvement sites | Peritoneum, omentum, mesentery |

| Types of surgical procedures | Laparotomy, hysterectomy, nodule excision |

| Average number of nodules | 10 |

| Range of follow-up periods | 3–49 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bucuri, C.E.; Ciortea, R.; Malutan, A.M.; Oprea, V.; Toma, M.; Roman, M.P.; Ormindean, C.M.; Nati, I.; Suciu, V.; Simon-Dudea, M.; et al. Disseminated Peritoneal Leiomyomatosis—A Challenging Diagnosis-Mimicking Malignancy Scoping Review of the Last 14 Years. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081749

Bucuri CE, Ciortea R, Malutan AM, Oprea V, Toma M, Roman MP, Ormindean CM, Nati I, Suciu V, Simon-Dudea M, et al. Disseminated Peritoneal Leiomyomatosis—A Challenging Diagnosis-Mimicking Malignancy Scoping Review of the Last 14 Years. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(8):1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081749

Chicago/Turabian StyleBucuri, Carmen Elena, Razvan Ciortea, Andrei Mihai Malutan, Valentin Oprea, Mihai Toma, Maria Patricia Roman, Cristina Mihaela Ormindean, Ionel Nati, Viorela Suciu, Marina Simon-Dudea, and et al. 2024. "Disseminated Peritoneal Leiomyomatosis—A Challenging Diagnosis-Mimicking Malignancy Scoping Review of the Last 14 Years" Biomedicines 12, no. 8: 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081749

APA StyleBucuri, C. E., Ciortea, R., Malutan, A. M., Oprea, V., Toma, M., Roman, M. P., Ormindean, C. M., Nati, I., Suciu, V., Simon-Dudea, M., & Mihu, D. (2024). Disseminated Peritoneal Leiomyomatosis—A Challenging Diagnosis-Mimicking Malignancy Scoping Review of the Last 14 Years. Biomedicines, 12(8), 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081749