Perioperative Multi-Kingdom Gut Microbiota Alters in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Metagenomic Sequencing Data Analysis and Functional Annotation of Species

2.3.1. DNA Extraction and Library Construction from Fecal Samples

2.3.2. Sequencing and Data Analysis

2.3.3. Taxonic and Functional Annotation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Changes in Gut Microbiology After Surgery

3.2.1. Bacterial Changes After Surgery

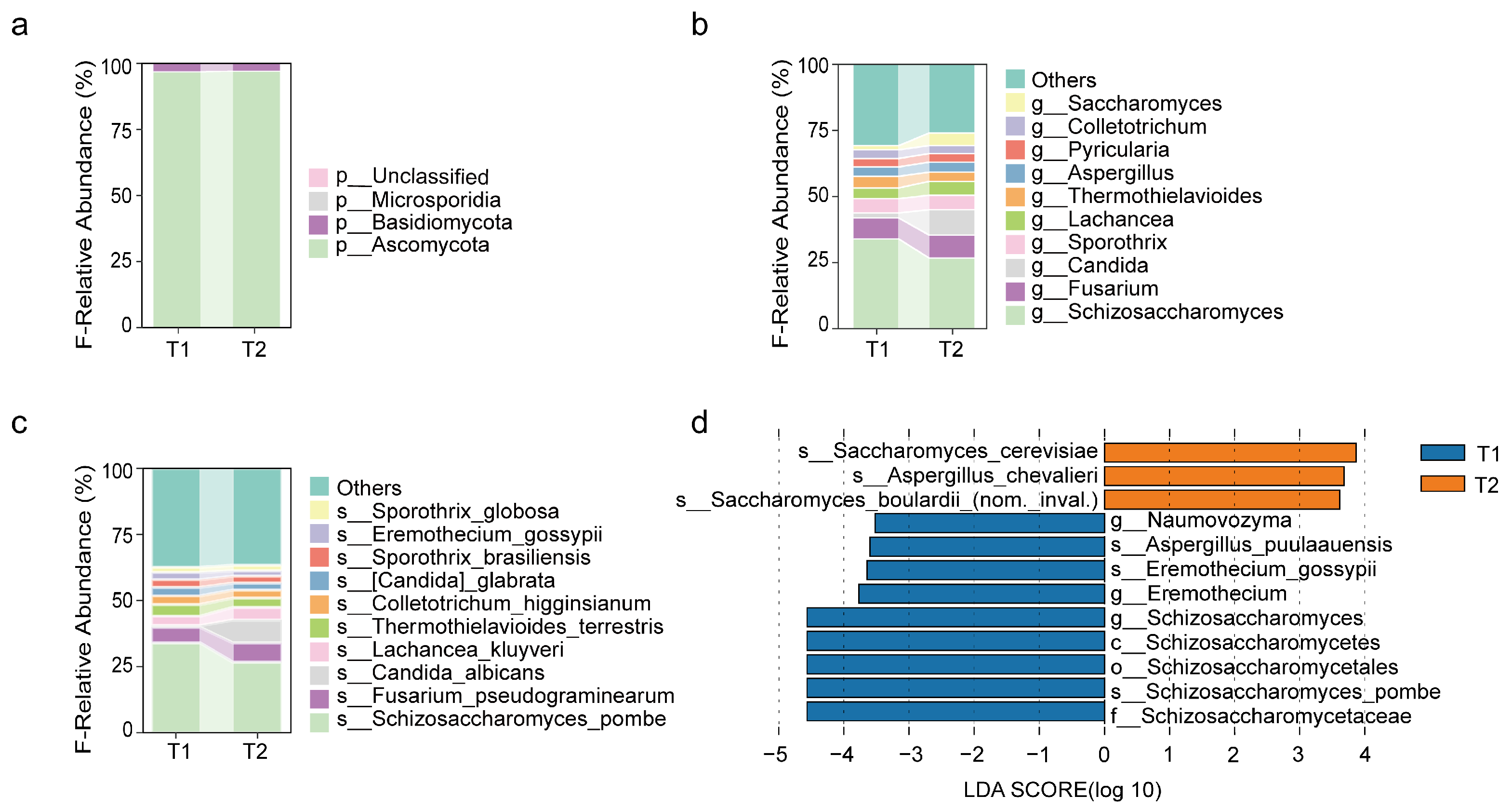

3.2.2. Changes in Fungal Communities After Surgery

3.2.3. Changes in Archaeal Communities After Surgery

3.2.4. Changes in Viral Communities After Surgery

3.2.5. Changes in Genes, Metabolic Pathways, and Resistance Genes After Surgery

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.3.1. Correlations Between Multi-Kingdom Species

3.3.2. Multi-Kingdom Species and Genes, Metabolic Pathways, and Resistance Genes

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Yu, L.; Zhu, K.; Du, N.; Si, Y.; Liang, J.; Shen, R.; Chen, B. Comparison of hybrid coronary revascularization versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 17, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Młynarska, E.; Czarnik, W.; Fularski, P.; Hajdys, J.; Majchrowicz, G.; Stabrawa, M.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. From Atherosclerotic Plaque to Myocardial Infarction-The Leading Cause of Coronary Artery Occlusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowski, E.J.; Kożuch, M.; Dobrzycki, S. Left Main Coronary Artery Disease-Current Management and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.D.; Verster, A.J.; Radey, M.C.; Schmidtke, D.T.; Pope, C.E.; Hoffman, L.R.; Hajjar, A.M.; Peterson, S.B.; Borenstein, E.; Mougous, J.D. Human gut bacteria contain acquired interbacterial defence systems. Nature 2019, 575, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aardema, H.; Lisotto, P.; Kurilshikov, A.; Diepeveen, J.R.J.; Friedrich, A.W.; Sinha, B.; de Smet, A.; Harmsen, H.J.M. Marked Changes in Gut Microbiota in Cardio-Surgical Intensive Care Patients: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, J.; Zhu, H.; Liu, D.; Li, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.; Lv, H.; Liu, K.; Hao, C.; Tian, Z.; et al. A Pilot Study: Changes of Gut Microbiota in Post-surgery Colorectal Cancer Patients. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahansepas, A.; Aghazadeh, M.; Rezaee, M.A.; Hasani, A.; Sharifi, Y.; Aghazadeh, T.; Mardaneh, J. Occurrence of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium in Various Clinical Infections: Detection of Their Drug Resistance and Virulence Determinants. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.O.; Singh, K.V.; Cruz, M.R.; Kaval, K.G.; Francisco, L.E.; Murray, B.E.; Garsin, D.A. Cardiac Microlesions Form During Severe Bacteremic Enterococcus faecalis Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, F. Current Knowledge of Enterococcal Endocarditis: A Disease Lurking in Plain Sight of Health Providers. Pathogens 2024, 13, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Bouza, E.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Eiros, J.M.; Pérez, M.J.; Sánchez-Somolinos, M.; Rincón, C.; Hortal, J.; Peláez, T. Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia: An emerging infectious disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2005, 40, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, J.; Singh, S.M. Aspergillus chevalieri (Mangin) Thom and Church: A new opportunistic pathogen of human cutaneous aspergillosis. Mycoses 1994, 37, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, L.; Perini Leme Giordano, A.L.; Reichert-Lima, F.; Gualtieri Beraquet, C.A.; Leite Pigolli, G.; Arai, T.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Watanabe, A.; Goldman, G.H.; et al. Insights into Aspergillus fumigatus Colonization in Cystic Fibrosis and Cross-Transmission between Patients and Hospital Environments. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.P.; Conway, P.L.; Schlundt, J. Methanogens in humans: Potentially beneficial or harmful for health. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 3095–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dridi, B.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. Archaea as emerging organisms in complex human microbiomes. Anaerobe 2011, 17, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catlett, J.L.; Carr, S.; Cashman, M.; Smith, M.D.; Walter, M.; Sakkaff, Z.; Kelley, C.; Pierobon, M.; Cohen, M.B.; Buan, N.R. Metabolic Synergy between Human Symbionts Bacteroides and Methanobrevibacter. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0106722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsola, S.L.; Prevodnik, A.A.; Sinclair, L.F.; Sanders, I.A.; Economou, C.K.; Eyice, Ö. Methanomethylovorans are the dominant dimethylsulfide-degrading methanogens in gravel and sandy river sediment microcosms. Environ. Microbiome 2024, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carding, S.R.; Davis, N.; Hoyles, L. Review article: The human intestinal virome in health and disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 800–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkoporov, A.N.; Hill, C. Bacteriophages of the Human Gut: The “Known Unknown” of the Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; You, X.; Mai, G.; Tokuyasu, T.; Liu, C. A human gut phage catalog correlates the gut phageome with type 2 diabetes. Microbiome 2018, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clooney, A.G.; Sutton, T.D.S.; Shkoporov, A.N.; Holohan, R.K.; Daly, K.M.; O’Regan, O.; Ryan, F.J.; Draper, L.A.; Plevy, S.E.; Ross, R.P.; et al. Whole-Virome Analysis Sheds Light on Viral Dark Matter in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 764–778.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomofuji, Y.; Kishikawa, T.; Maeda, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Nii, T.; Okuno, T.; Oguro-Igashira, E.; Kinoshita, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Sonehara, K.; et al. Whole gut virome analysis of 476 Japanese revealed a link between phage and autoimmune disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Gong, J.; Lu, T.; Yuan, L.; Lan, Y.; Tu, X. Characteristics of intestinal bacteriophages and their relationship with Bacteria and serum metabolites during quail sexual maturity transition. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liang, H.; Lu, J.; He, Y.; Lai, R. Probiotics Improve Postoperative Adaptive Immunity in Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 2975–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhu, P.; Shi, L.; Gao, N.; Li, Y.; Shu, C.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y.; He, J.; Guo, D.; et al. Bifidobacterium longum promotes postoperative liver function recovery in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 131–144.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Yang, H.; Zhong, Z.; Luo, C.; Huang, Q.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Xiang, H.; Tang, Y.; Chen, T. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis LPL-RH improves postoperative gastrointestinal symptoms and nutrition indexes by regulating the gut microbiota in patients with valvular heart disease: A randomized controlled trial. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 7605–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 40 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.55 ± 8.06 |

| Male (N, %) | 31 (77.5%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.05 ± 3.42 |

| Smoking (N, %) | 21 (52.2%) |

| Drinking (N, %) | 12 (30%) |

| Hypertension (N, %) | 25 (62.5%) |

| Diabetes mellitus (N, %) | 19 (47.5%) |

| Hyperlipidemia (N, %) | 18 (45%) |

| Heart rate (bpm/min) | 73 ± 14 |

| Planned operation | |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) (N %) | 20 (50%) |

| Hybrid Coronary Revascularization (HCR) (N, %) | 20 (50%) |

| Exposure antibiotics | |

| Days of β-lactamase (days) | 7.35 ± 4.89 |

| Chronic kidney failure (N, %) | 2 (5%) |

| Postoperative sample collection time (days) | 7.4 ± 4.0 |

| Omeprazole/Pantoprazole (N, %) | 40 (100%) |

| Anesthesia | |

| Intravenous Anesthetics (N, %) | 12 (30%) |

| Intravenous + Inhalational (N, %) | 28 (70%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130 ± 15 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75 ± 11 |

| Days of hospital(days) | 20.5 (17.25, 25.75) |

| Syntax score | 28.33 ± 6.50 |

| Clinical Indicators | Preoperative | Postoperative | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (109/L) | 6.06 (5.69, 7.81) | 10.47 (7.82, 11.70) | 0.000 |

| NE (109/L) | 3.82 (3.10,4.48) | 9.02 (6.84, 10.52) | 0.000 |

| LY (109/L) | 1.84 ± 0.68 | 0.74 ± 0.36 | 0.000 |

| SII | 450.98 (325.22, 667.70) | 2281.72 (1049.80, 3123.47) | 0.000 |

| Cr (umol/L) | 68.80 (63.68, 80.20) | 81.83 (66.18, 92.00) | 0.001 |

| UREA (mmol/L) | 6.36 ± 2.07 | 5.42 ± 1.63 | 0.006 |

| URIC (umol/L) | 334.00 ± 71.27 | 245.92 ± 71.27 | 0.010 |

| ALT (U/L) | 23.50 (16.00, 31.00) | 32.50 (23.25, 46.87) | 0.017 |

| AST (U/L) | 21.00 (18.25, 34.00) | 35.00 (26.25, 49.50) | 0.003 |

| TNI (ng/mL) | 0.16 (0.00, 6.20) | 16.98 (0.40, 778.10) | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, Z.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Y.; Xie, B.; An, K.; Yuan, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, J.; Tong, Z.; et al. Perioperative Multi-Kingdom Gut Microbiota Alters in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13020475

Fu Z, Jia Y, Zhao J, Guo Y, Xie B, An K, Yuan W, Chen Y, Zhong J, Tong Z, et al. Perioperative Multi-Kingdom Gut Microbiota Alters in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(2):475. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13020475

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Zhou, Yanxiong Jia, Jing Zhao, Yulin Guo, Boqia Xie, Kun An, Wen Yuan, Yihang Chen, Jiuchang Zhong, Zhaohui Tong, and et al. 2025. "Perioperative Multi-Kingdom Gut Microbiota Alters in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting" Biomedicines 13, no. 2: 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13020475

APA StyleFu, Z., Jia, Y., Zhao, J., Guo, Y., Xie, B., An, K., Yuan, W., Chen, Y., Zhong, J., Tong, Z., Liu, X., & Su, P. (2025). Perioperative Multi-Kingdom Gut Microbiota Alters in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Biomedicines, 13(2), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13020475