Abstract

Background: During the various stages of education, adolescents undergo emotional and motivational experiences that can play key roles in their development. This study aims to analyse the relationship among academic self-efficacy, optimism, and academic performance. Methods: This study comprised 1852 adolescent (male, N = 956, 51.61% and female, N = 896, 48.38%) aged 12–19 years (M = 14.77; SD = 1.80) from twelve secondary schools in Spain. The instruments used for the evaluation were the Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES) and the Life Orientation Test—Revised (LOT-R); the students’ average marks were used to measure their academic performance. Results: The results of the study revealed significant correlations among self-efficacy, optimism and academic performance. Conclusions: These results emphasise the importance of academic self-efficacy as a mediating variable between the other two variables as well as its central role in the promotion of adaptive behaviours in the classroom, leading to adequate personal development, helping to prevent early school dropout and contributing to a more satisfactory academic experience.

1. Introduction

During students’ school years, they face numerous personal and contextual situations that can have a significant impact on their development, especially during adolescence, a key period for their academic and personal growth in the life cycle, when adult personality is forged [1].

Some students will pass this stage of life without difficulties at the academic and personal levels, but others, conditioned by various variables, may stagnate at some point and be affected by some psychological variables that in turn affect their academic performance [2].

For this reason, research on certain psychological variables can cause a positive impact in the school context and help in understanding the cognitive and motivational processes that can lead to personal and academic improvements [3].

Self-efficacy plays an important role in the learning process and in the way students face their school tasks [4]. In academic contexts, self-efficacy is a self-regulatory mechanism that affects the academic behaviour of students in that it determines the student’s perception of their own competence towards a given task and their ability to adapt to and cope with future academic demands [5].

As such, students with higher levels of self-efficacy perceive homework to be a challenge to be faced with confidence in their own ability and to practice their skills responsibly and efficiently [6]. Empirical research has shown that academic self-efficacy can be used to predict students’ participation and commitment towards school tasks [7]; perseverance and motivation [8]; academic performance [9]; and more broadly, greater levels of academic satisfaction and happiness [10]. Conversely, low levels of self-efficacy have been related to low commitment and poor academic performance [11] and have even lead to psychological conditions such as anxiety and stress [12,13].

Another important variable for self-perception in a variety of contexts is optimism, defined as a more or less stable set of positive expectations concerning future experiences [14].

Optimism is a personal pre-disposition that mediates between external conditions and the way we interpret them, affecting decision-making processes. While optimistic individuals tend to respond positively to adverse events, hence overcoming them, less optimistic individuals are less capable of responding to negative, critical, and even traumatic experiences [15].

The existing literature on optimism in academic contexts established that this factor can be used to predict other psychological variables. Optimistic students who use adaptive coping strategies [16] and present higher levels of personal and academic self-efficacy [17] are more likely to meet their personal and academic targets [18], are less vulnerable [19], present higher levels of self-concept and self-esteem, and are more assertive [20,21,22].

In short, optimism plays a crucial role in the way individuals confront everyday experiences, especially during adolescence, during which their adult personality is formed [14].

Finally, academic performance is understood as the quantitative/qualitative assessment of academic achievements during the learning process [23]. The scientific literature has been based mainly on two measures that assess and determine the academic performance of students: from a quantitative point of view, obtaining school grades and, from a more qualitative point on view, focused on their personal variables and context [24].

On the one hand, average for school grades has always served as a representative evaluation of students’ academic performance [25]. On the other hand, certain authors defend other types of evaluations as being better representatives of academic performance such as the number of repeated school years and even the time dedicated to student assimilation [26,27].

Academic performance in adolescents is a broad construct that has been approached from some perspectives and theoretical references. Gónzalez [28] emphasises the intrapersonal factors that determine the personality of adolescent students; Fierro, Almagro, and Sáenz-López [29] focus on all of those socio-emotional variables, especially the motivational processes that direct the behaviour of students. Pulido and Herrera [30] attached importance to the value of the influence of sociodemographic variables in the context closest to the student body.

For all of these reasons, following the study by Méndez [31], studies that advocate the interactive processes of students are necessary to learn first-hand about other variables that directly influence the academic performance of students not only to improve their grades but also to work with all of the underlying variables that affect personal development in students [32].

In this way, there are not many manuscripts that relate study variables to academic performance or other variables that play important roles in the study of factors that determine academic performance. Therefore, the objective of this research was to analyse the relationship among the variables self-efficacy, optimism, and academic performance in adolescent students.

The two main hypotheses of this investigation were as follows:

- (a)

- Self-efficacy is linked to optimism and academic performance, stimulating adaptive behaviours;

- (b)

- The relationship between optimism and students’ academic performance will be mediated by self-efficacy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The study population comprised 1852 students (male, N = 956, 51.61% and female, N = 896, 48.38%) in 12 schools, with ages ranging 12–19 years (M = 14.77; SD = 1.80). The inclusion criteria were the ability to read and communicate, as a necessary condition to understand the questionnaires. Incomplete questionnaires (29) and students with cognitive disorders, which hampered a complete understanding of the questionnaires, were excluded. The different schools in the sample were chosen by simple random sampling through the completion of a questionnaire; 98.89% of questionnaires were returned and counted.

First, with the objective to evaluate the self-efficacy of students, the Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES) was used, validated by García, Inglés, Torregrosa, Ruiz, Díaz, Pérez, and Martínez (2010) for adolescent students [33]. The scale comprises 10 individual items to evaluate self-efficacy in an academic context (for example, “I am convinced that I can carry out outstanding exams”). The responses to the questionnaire ranged from 1 to 5 points on a Likert-type scale, where 1 point means “Strongly disagree” (1) and 5 points means “Strongly agree” (5). The value of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91, demonstrating high reliability in school environments, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha in our study of 0.89.

Concerning optimism, Scheier, Carver, and Bridges’s (1994) [34] Life Orientation Test—Revised (LOT-R) was translated and validated into Spanish for adolescents by Ferrando, Chico, and Tous (2002) [35]. The scale includes six items, three of which are positive statements (for example, “I am always optimistic about my future”) and the other three being negative statements (for example, “I hardly ever expect things to go my way”). The answers to the questions were determined on a scale from 1 to 5 points on a Likert-type scale, where 1 point means “Strongly disagree” (1) and 5 points means “Strongly agree” (5). The value of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78, demonstrating high reliability in academic and school environments, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha in our study of 0.79.

Finally, the variable academic performance was evaluated on the basis of the average marks in the first trimester, ranging from 0 to 10 (minimum/maximum). This variable is widely used and regarded as an effective predictor of students’ academic performance [25,36,37]. For our study, this variable yielded a Cronbach-α of 0.86.

2.2. Protocol

The questionnaires were handed out to the students in their classrooms. All students from each school receiving the questionnaire on the same day provided signed informed consent from the parents/guardians in advance, coordinated with the school’s management. At all times, parents and students were informed of the objectives of the investigation and that their participation was voluntary, which is in line with the ethical directives set out in the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) [38]. The protocol was endorsed by the Opiics Research Group (46_20R, 2020–2022) (Psychology and Sociology Deparment of he University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, 5009). Questionnaires were anonymous and confidential, and students could opt out at any point in the process.

2.3. Data Analysis

First, to establish the sociodemographic data of the students, descriptive statistics of the variables sex, age, academic year, type of study, and number of repetitions for the academic year and the variables self-efficacy, optimism, and academic performance were analyzed. After performing the descriptive analysis, bivariate correlations were made between the three study variables using IBM SPSS v26.0. Subsequently, a cluster analysis was executed to compare the sample in three significant groups, with each other using K-means in a cluster. Finally, a bootstrapping mediation analysis (10,000 runs) was performed in order to give the proposed model adequacy and confidence using a confidence level of 5% and p ≤ 0.05 at the significance.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Variables of the Study

The study comprised 1852 adolescent (male, N = 956, 51.61% and female, N = 896, 48.38%) aged 12–19 years (M = 14.77; SD = 1.80), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic features of the sample.

3.2. Descriptive Variables of the Study

The values for the variables self-efficacy, optimism, and academic performance are highly variable, as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive values of the variables.

Optimism was shown to be of little statistical significance and slightly higher in males (Cohen’s d = 0.285). Males scored slightly higher in the variable self-efficacy, while females scored slightly higher in academic performance.

3.3. Correlational Analysis of the Study

As seen in Table 3, we can observe some correlations in all variables, which are related in different ways. Self-efficacy is positively correlated with optimism (r = 0.375) and academic performance (r = 0.370), while optimism showed a much weaker correlation with academic performance (r = 0.106) than self-efficacy (r = 0.375)

Table 3.

Values of the correlational analysis.

3.4. Cluster Analysis of Statistically Significant Groups of the Students

Three significant groups were made through a K-means cluster analysis to divide the students into three significant groups among them.

Group nº 1 (N = 596, 32.18%) was characterised by low scores in self-efficacy, optimism, and academic performance; Group º2 (N = 616, 33.26%) presented variable scores, with near average scores in self-efficacy, high scores in optimism, and poor academic performance; finally, Group nº 3 (N = 640, 34.55%) was characterised by high scores in self-efficacy, optimism, and academic performance, as illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Values of the cluster analysis.

3.5. Mediation of the Effects of Self-Efficacy between Optimism and Academic Performance of Students

To establish whether the relationship between optimism and academic performance is mediated by self-efficacy, we used MACRO by Hayes (2018) [39] in SPSS Process 3.0 (v 26.0), continuing the methodology proposed by Tal-Or, Cohen, Tsarfati, and Gunther (2010) [40].

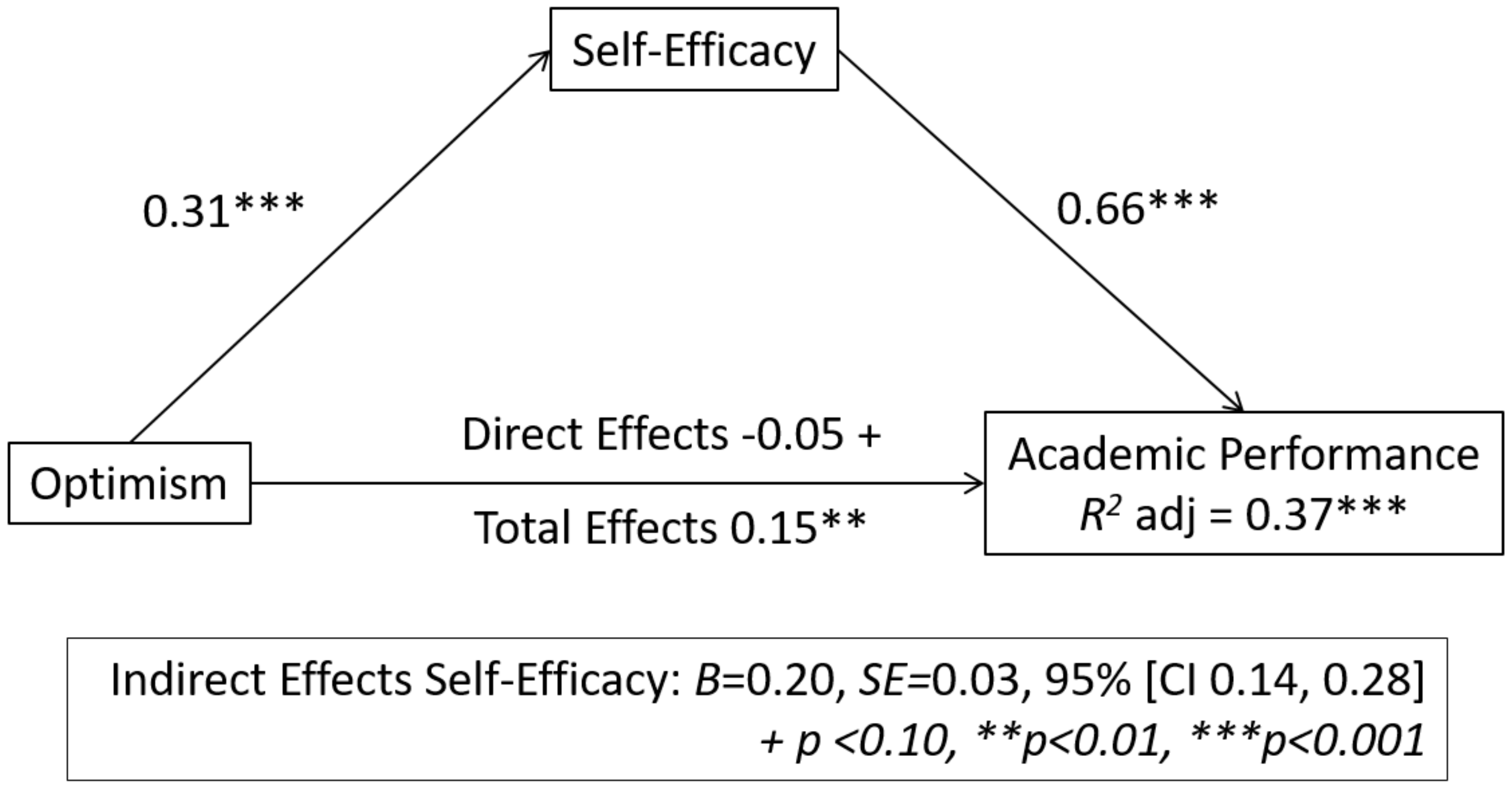

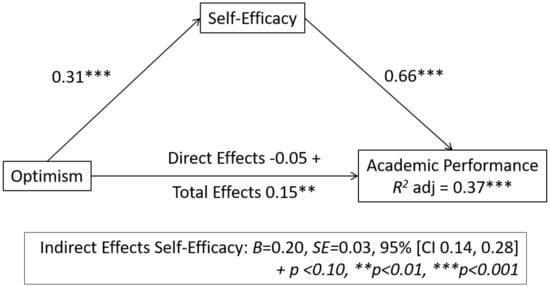

In Figure 1, we can see that self-efficacy plays a significant mediating effect on the relationship between optimism and academic achievement. Thus, the results indicate a mediating effect of optimism (VI) on self-efficacy of 0.31 m and a mediating effect of self-efficacy on academic performance (VD) of 0.66; in both cases, p > 0.001, which therefore, is statistically significant. Zero was not included in the bootstrap interval, B = 0.20, SE = 0.03, and 95% [CI 0.14, 0.28], so it can be stated that mean self-efficacy has a positive relationship with optimism and academic performance.

Figure 1.

Values of the mediating role of self-efficacy in the variables of the study.

These findings establish that optimism by itself does not have a direct significant effect on academic performance (−0.05, p < 0.10) but that its combination with self-efficacy does, yielding a result of 0.15, p < 0.001 (direct effect + indirect effect), with the proportion of variance being explained by the model R2 = 0.37 ***.

These results suggest the role that self-efficacy plays in its relationship with optimism and academic performance, and the practical implications that it may entail.

4. Discussion

The results of our research aimed to analyse the intrinsic relationship among self-efficacy, optimism, and academic performance on a sample of school-age adolescents.

The first hypothesis raised was confirmed based on our findings. Namely, the results show that self-efficacy is positively correlated with optimism and academic performance.

Our finding is in line with other studies in the scientific literature. Alejos (2018) [41] established a relationship between academic self-efficacy and optimism as key factors in student happiness; De Besa, Gil, and García (2019) [42] showed that various individual psycho-social features determine the level of optimism, such as self-efficacy and learning strategies; Rand (2018) [43] showed the close relationship between optimism and self-efficacy in adolescent students in a study that dealt with self-confidence and hopes for the future; Fínez and Morán [44] drew a link between intrapersonal self-evaluation factors, such as self-concept, self-esteem, and self-efficacy, and resilience in adolescent students; finally, Liu et al. (2018) [45] pointed out that self-efficacy and optimism can be used to predict student subjective wellbeing.

On the other hand, the relation between self-efficacy and academic performance has been paid greater attention in a scholarly context. Some studies establish a direct relationship between these variables; Avalos, Oropeza, Ramírez, and Palos (2018) [46], and Galleguillos and Olmedo (2017) [47] found statistically significant correlations between self-efficacy and academic performance; Castro (2020) [48] drew a similar link in both primary and secondary school contexts.

Other studies have examined the relationship between self-efficacy and academic performance in broader studies that take into consideration more variables, such as study strategies, coping styles, resilience and self-esteem, the development of creativity, and commitment and motivation towards school tasks [9,28,49,50].

The second hypothesis that we made in the investigation was also confirmed; that is, self-efficacy remained as a mediating variable between optimism and academic performance. In this way, we can affirm that the academic self-efficacy of the adolescent students in the study influences the relationship between the other two variables. However, these results must be carefully commented on since, although they present bidirectional correlations with each other, optimism is a poor predictor of academic performance; that is, the effect of the former on the latter is not statistically significant.

The current scientific literature is divided about this issue. Some studies find that optimism can predict academic performance: for example, Pulido and Herrera (2018) [51] in a sample of secondary school students and Kolovelonies and Goudas (2018) in primary school students, among others [52,53,54]. Other studies, however, argue against the predictive value of optimism over academic performance [17,55,56], in agreement with our own results.

The results suggest that self-efficacy plays a mediating role between the other two variables, which only emphasises the importance of this variable for adolescent students, especially by mediating between optimism and academic performance. This has relevant practical implications.

There are some investigation that examine these variables from different points of view, but no previous investigation have directly addressed the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship with optimism and academic performance. Alhadabi and Karpinski (2020) [57] established the mediating role of self-efficacy between more intrinsically oriented academic motivations and school performance; Usher, Li, Butz, and Rojas (2019) [58] reached similar conclusions with a sample of students in different educational tiers; Avalos, Oropeza, Ramírez, and Palos (2018) [46] established the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship with academic skills and achievements; Cerezo et al. (2019) [59] established a direct correlation between training in self-regulated learning strategies and an increased understanding of said strategies, a relationship in which self-efficacy plays a mediating role. Alipio (2020) [60] alluded to the influence of self-efficacy on value expectancy beliefs about students’ academic performance. Udavar, Fiori, and Bausseron (2020) [61] found that the relationship between achievement and emotional intelligence was supported by the modulation of the self-efficacy of adolescents.

5. Conclusions

For these reasons, the important role played by the constructs used in our research is highlighted, which together with the personal and contextual circumstances of students, can directly affect school performance [62].

The limitations of this study are chiefly related to its lateral nature. Data collection was a one-off event, and as a result, the data have no temporal depth, while scores can easily change significantly from year to year and even within the same school year. In a similar fashion, the schools were randomly selected in terms of type of school, students and teachers, socioeconomic conditions, and social/cultural settings.

Future studies should examine the role that self-efficacy plays for students as well as its influence on other psychological variables. That students feel competent in their school tasks is a prerequisite for other adaptive behaviours and an adequate personal and academic development. It is also necessary to undertake longitudinal studies that allow for an examination of the evolution of these constructs over a longer time span, although the methodological challenges that these studies pose must be recognised. In addition, it would be interesting to take into consideration other academic tiers, such as primary school (6–11 years) and university (18 years and over). It would also be of interest to take into consideration other sociodemographic variables, such as gender, age, and type of school (public, private, and rural environments). Similarly, programmes directed by psychology and educational professionals can also help to improve students’ overall experience, decreasing the risk of early school dropout.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: C.S., P.U. and A.Q.-R.; data curation, C.S., P.U. and A.Q.-R.; investigation, C.S., P.U. and A.Q.-R.; methodology, C.S., P.U. and A.Q.-R.; supervision, C.S., P.U. and A.Q.-R.; writing—original draft, C.S., P.U. and A.Q.-R.; writing—review and editing, C.S., P.U. and A.Q.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was performed by Research Group OPIICS (S46_20R), University of Zaragoza (Zaragoza, Spain), and was supported by research funds provided by the Department of Science and Technology of the Government of Aragón (Spain) and the European Social Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the OPIICS research group (S46_20R), Psychology and Sociology Department, Universidad de Zaragoza, on 26 February 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

All students were volunteers and signed an informed consent form.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding autor.

Acknowledgments

Universidad de Zaragoza, Fundación Bancaria Ibercaja y Fundación CAI (Ref. CH 17/21).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this research.

References

- Longobardi, C.; Prino, L.E.; Marengo, D.; Settanni, M. Student-teacher relationships as a protective factor for school adjustment during the transition from middle to high school. Front. Psy. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreno, S.; Haro, O.; Freire, P. Relation between academic performance and attendance as factors of student promotion. Rev. Cátedra 2019, 2, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, X. Adolescencia: ¿una etapa problemática del desarrollo humano? Rev. Cienc. Sal. 2019, 17, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2006; Volume 5, pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Rosal, I.; Bermejo, M. Autoeficacia en estudiantes universitarios: Diferencias entre el grado de maestro en educación primaria y los grados en ciencias. Inter. J. Dev. Educ. Psy. 2017, 1, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.M.; Inglés, C.; Vicent, M.; Gonzálvez, C.; Pérez, A.; San Martín, N. Escala de Autoeficacia Percibida Específica de Situaciones Académicas en Chile y su Relación con las Estrategias de Aprendizaje. Rev. Iber. Diag. Eval. 2016, 41, 118–131. [Google Scholar]

- Galyon, C.E.; Blondin, C.A.; Yaw, J.S.; Nalls, M.L.; Williams, R.L. The relationship of academic self-efficacy to class participation and exam performance. Soc. Psy. Educ. 2012, 15, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Posada, A.; Liu, Y. The moderating effects of gender on the relationship between academic stress and academic self-efficacy. Inter. J. Str. Manag. 2018, 25, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honicke, T.; Broadbent, J. The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 17, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakman, A.; Kinney, A.; Schierl, M.; Henry, K. Academic performance in student service members/veterans: Effects of instructor autonomy support, academic self-efficacy and academic problems. Educ. Psy. 2019, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Chiu, C.; Owens, B.; Brown, J.; Liao, J. Growing Followers: Exploring the Effects of Leader Humility on Follower Self-Expansion, Self-Efficacy, and Performance. J. Manag. Stu. 2019, 56, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. Academic Self-Efficacy, Coping, and Academic Performance in College. Int. J. Under. Res. Creat. Act. 2013, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keye, M.D.; Pidgeo, A.M. An investigation of the relationship between resilience, mindfulness, and academic self-efficacy. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Dispositional optimism. Trends Cog. Sci. 2014, 18, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro, J.; Guzmán, J.; Sirlopú, D.; García, C.; Reyes, F.; Gaudlitz, L. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en los Estudiantes (SLSS) de Huebner en niños y niñas de 10 a 12 años de Chile. Anal. Psic. 2016, 32, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabras, C.; Mondo, M. Coping strategies, optimism, and life satisfaction among first-year university students in Italy: Gender and age differences. High. Educ. 2018, 75, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, K.; Martin, A.; Shea, A. Hope, but not optimism, predicts academic performance of law students beyond previous academic achievement. J. Res. Pers. 2011, 45, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodarahmi, E.; Zarrinabadi, N. Self-Regulation and Academic Optimism in a Sample of Iranian Language Learners: Variations across Achievement Group and Gender. Curr. Psy. 2016, 35, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, B. Testing a model of subjective well-being: The roles of optimism, psychological vulnerability, and shyness. Health Psych. Open 2019, 6, 2055102919884290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, I.T.; Rico, T.P. Psicología Positiva y Promoción de la Salud Mental. Emociones Positivas y Negativas. In Aplicaciones Educativas de la Psicología Positiva; En, A.C., Vãnó, R., Eds.; Generalitat Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 2010; pp. 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, E.; Ortega, N.; Escobar, J.; García, R. Evaluación de la asertividad en estudiantes universitarios con bajo rendimiento académico. Rev. Cient. Elect. Psic. 2009, 9, 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- León, A.; Rodríguez, C.; Ferrel, F.; Ceballos, G. Asertividad y autoestima en estudiantes de primer semestre de la facultad de ciencias de la salud de una universidad pública de la ciudad de Santa Marta (Colombia). Rev. Psic. Desde Car. 2009, 24, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Garbanzo, G. Factores asociados al rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios desde el nivel socioeconómico: Un estudio en la Universidad de Costa Rica. Rev. Elect. Educ. 2013, 17, 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J. Medición del nivel socioeconómico familiar en el alum¬nado de Educación Primaria. Rev. Educ. 2011, 362, 298–322. [Google Scholar]

- Córdoba, L.; García, V.; Luengo, L.; Vizuete, M.; Feu, S. How academic career and habits related to the school environment influence on academic performance in the physical education subject. Retos 2012, 21, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, C.; Sánchez, P.; Bakieva, M. Actividades extraescolares y rendimiento académico: Diferencias en autoconcepto y género. Rev. Inv. Educ. 2011, 29, 447–465. [Google Scholar]

- Hernando, A.; Oliva, A.; Pertegal, M. Variables familiares y rendimiento académico en la adolescencia. Est. Psic. 2012, 33, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.I. Autoestima, Optimismo y Resiliencia en Niños en Situación de Pobreza. Rev. Int. Psic. 2018, 16, 2–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro, S.; Almagro, B.J.; Sáenz-López, P. Necesidades psicológicas, motivación e inteligencia emocional en Educación Física. Rev. Elect. Inter. Form. Prof. 2019, 22, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, F.; Herrera, F. Influencia de la felicidad en el rendimiento académico en primaria: Importancia de las variables sociodemográficas en un contexto pluricultural. Rev. Esp. Orien. Psicop. 2019, 30, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, J. Autoconcepto académico y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de la Universidad de la Frontera: Análisis comparative por facultades. Rev. Invest. Educ. 2016, 26, 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Vizoso, C.; Arias, O. Resiliencia, optimismo y burnout académico en estudiantes universitarios. Europ. J. Educ. Psy. 2018, 11, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.M.; Inglés, C.; Torregrosa, M.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; Díaz, A.; Pérez, E.; Martínez, M. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Autoeficacia Percibida Específica de Situaciones Académicas en una muestra de estudiantes españoles de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Eur. J. Educ. Psy. 2010, 3, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Distinguising optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self mastery and self este-em): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Pers. Soc. Psy. 1994, 67, 1.063–1.078. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Chico, E.; Tous, J.M. Propiedades psicométricas del test de optimismo Life Orientation Test (LOT). Psicothema 2022, 14, 673–680. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, A.; Peralbo, M.; Porto, A.; Marcos, J.; Brenlla, J. Metas académicas del alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO) y Bachillerato con alto y bajo rendimiento escolar. Rev. Educ. 2011, 354, 341–368. [Google Scholar]

- Risso, A.; Peralbo, M.; Barca, A. Cambios en las variables predictoras del rendimiento escolar en Enseñanza Secundaria. Psicothema 2010, 22, 790–796. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación Médica Mundial. Declaración de Helsinki. Principios Éticos Para las Investigaciones con los Seres Humanos; AMM: Seoul, Korea, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tal-Or, N.; Cohen, J.; Tsarfati, Y.; Gunther, A. Testing causal direction in the influence of presumed media influence. Sage Open 2010, 37, 801–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejos, C. Autoeficacia y Optimismo Atributivo en la Determinación de la Felicidad en Estudiantes de una Universidad Privada de Lima Sur. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma del Perú, Lima, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Besa, M.R.; Gil, J.; García, A.J. Variables psicosociales y rendimiento académico asociados al optimismo en estudiantes universitarios españoles de nuevo ingreso. Act. Colom. Psic. 2019, 22, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, K.L. Hope, self-efficacy, and optimism: Conceptual and empirical differences. In The Oxford Handbook of Hope; Oxford Library of Psychology; Gallagher, M.W., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fínez, M.J.; Morán, C. Resiliencia y autovaloraciones esenciales: Estudio comparativo en adolescentes y jóvenes. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2017, 9, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Hsu, A.; Chen, C.; Liu, J.; Yu, G. Optimism and self-efficacy mediate the association between shyness and subjective well-being among Chinese working adults. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, M.L.; Oropeza, R.; Ramírez, J.C.; Palos, M.U. Percepción de autoeficacia y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de bachillerato. Rev. Cienc. Soc. Hum. 2018, 22, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleguillos, P.; Olmedo, E.M. Autoeficacia académica y rendimiento escolar: Un estudio metodológico y correlacional en escolares. ReiDoCrea 2017, 6, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M. Autoeficacia y Rendimiento Académico en Adolescentes de un Centro de Educación Técnico Productiva. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad César Vallejo, Lima, Peru, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, J.G.; Medina, A.R. Enfoques de aprendizaje, autorregulación y autoeficacia y su influencia en el rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios de Psicología. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2019, 9, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, A.; Bandura, A.; Locke, E.; Lee, D.; Sergent, K. Test of three conceptual models of influence of the big five personality traits and self-efficacy on academic performance: A meta-analytic path-analysis. Pers. Indiv. Diff. 2018, 120, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, F.; Herrera, F. Estados emocionales contrapuestos como predictores del rendimiento académico en secundaria. Rev. Inv. Educ. 2018, 37, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; González, A.; Trianes, M. Relaciones entre estrés académico, apoyo social, optimismo-pesimismo y autoestima en estudiantes universitarios. Electr. J. Res. Educ. Psy. 2015, 13, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.; Youssef, C.; Chambel, M.; Marques, A. Antecedents of academic performance of university students: Academic engagement and psychological capital resources. Educ. Psy. 2019, 39, 1047–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizoso, C.; Arias, C.; Rodríguez, C. Exploring coping and optimism as predictors of academic burnout and performance among university students. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewine, R.; Sommers, A. Unrealistic Optimism in the Pursuit of Academic Success. Int. J. Schol. Teach. Learn. 2016, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mackenzie, S.; Fischer, I.; Rand, K. Hope, optimism, and affect as predictors and consequences of expectancies: The potential moderating roles of perceived control and success. J. Res. Pers. 2020, 84, 103903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadabi, A.; Karpinski, A. Grit, self-efficacy, achievement orientation goals, and academic performance in University students. Inter. J. Adol. Youth 2020, 25, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, E.; Li, C.; Butz, A.; Rojas, J.P. Perseverant grit and self-efficacy: Are both essential for children’s academic success? J. Educ. Psy. 2019, 111, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, R.; Fernández, E.; Amieiro, N.; Valle, A.; Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C. Mediating Role of Self-efficacy and Usefulness between Self-Regulated Learning Strategy Knowledge and Its Use. Rev. Psicodid. 2019, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipio, M. Predicting Academic Performance of College Freshmen in the Philippines using Psychological Variables and Expectancy-Value Beliefs to Outcomes-Based Education: A Path Analysis. Educ. Adm. EdArXiv 2020, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udavar, S.; Fiori, M.; Bausseron, E. Emotional intelligence and performance in a stressful task: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Pers. Ind. Diff. 2020, 156, 109790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, R.; Pérez, J.C.; García, E. Inteligencia Emocional en Educación; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).