Abstract

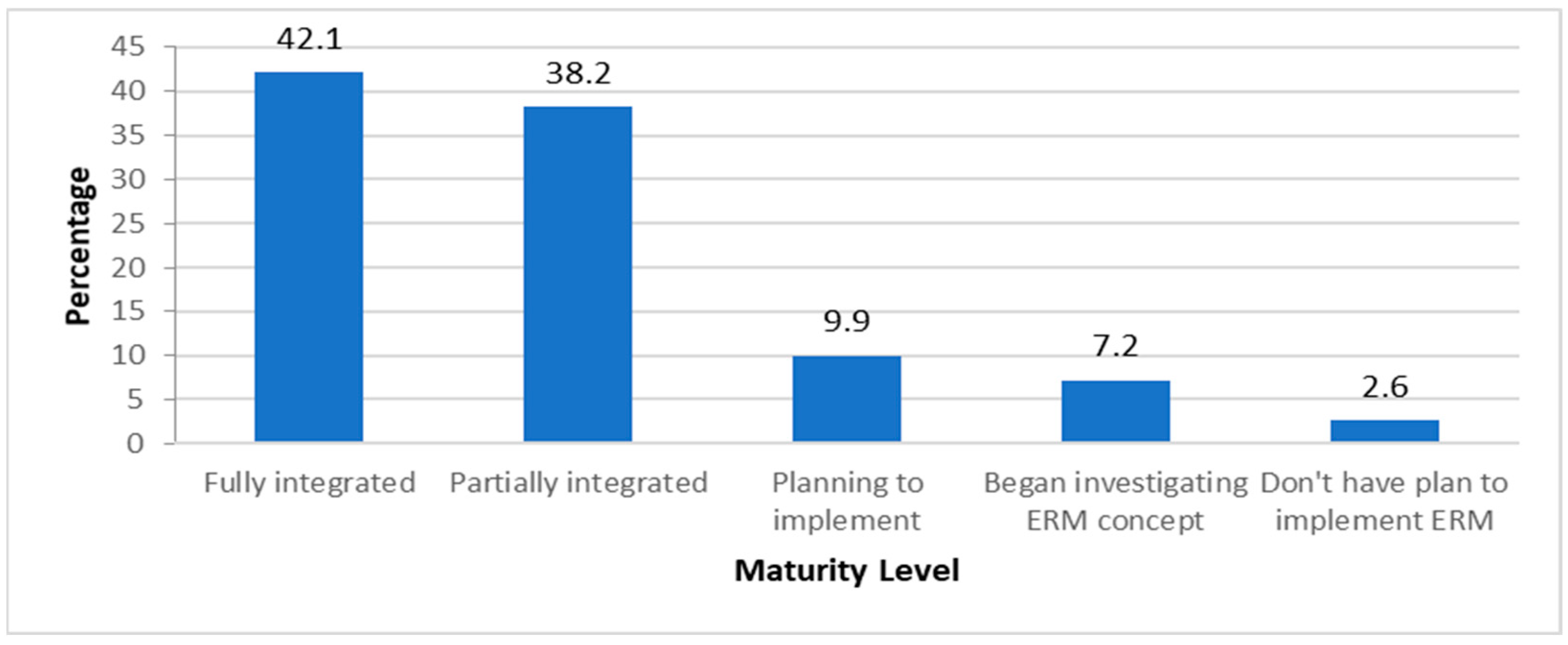

The study aims to examine the enterprise risk management (ERM) practices of Ethiopian commercial banks. This approach is undertaken to examine the current approach to enterprise risk management within the Ethiopian banking context. A mixed-methods research design is employed which comprises content analysis and a survey study. The study found that the prevailing emphasis of risk management functions in Ethiopian commercial banks revolves on ensuring compliance with regulatory reporting standards. A significant number of the banks have implemented ERM programs primarily to meet regulatory obligations, rather than leveraging ERM to generate firm value. The study identified several gaps in the risk management function of Ethiopian commercial banks, including lack of integration of risk management with the banks’ mission and core values, failure to assess the resources required for effective risk management and to prioritise resource allocation accordingly, inadequate coverage of relevant activities and functional areas by both risk management and internal audit activities, and limitations on the assignment of chief risk officers (CROs) to oversee the risk management function within the banks. Overall, the maturity level of ERM implementation among Ethiopian commercial banks is moderate and requires further enhancement.

1. Introduction

Banks play the role of catalysts for economic development and growth by providing a wide range of financial services for investments (Rundassa and Batra 2016, p. 108; Mutava and Ali 2016, p. 15). In the process of financial intermediary, banks are exposed to both financial and non-financial risks (Attarwala and Balasubramaniam 2015, p. 10). Risk management is fundamental for the sustainable growth of organisations (Abdullah et al. 2017, p. 2).

The function of risk management in the banking sector has been improved in recent years, mainly to comply with the regulations that resulted from the global financial crisis and the measures taken to improve the resilience of the financial institutions (Härle et al. 2016, p. 5). Lately, the concept of risk management has further improved. It has transformed from the traditional silo approach to the holistic one. Enterprise risk management (ERM) has become a global standard across the world to manage organisational risks due to the failure of the traditional risk-based approach (Olayinka et al. 2017, p. 938). Härle et al. (2016, p. 3) also noted that the transformation of bank risk management is afoot, which implies risk management will be practiced even more widely in the future.

The banking business in Ethiopia started during the reign of Emperor Menelik II in 1905. The Bank of Abyssinia, the first bank in Ethiopia, started its operation on 17 February 1905, to issue currency notes and engage in commercial banking (Alemayehu and Teklemedhin 2012, p. 1; Chanie 2015, p. 130). Later in 1932, the Bank of Abyssinia changed to the Bank of Ethiopia. Formerly, it was owned by Egyptian investors, and now it is owned by Ethiopian shareholders. During 1974–1991, the government nationalised financial institutions and the banking sector became a fragile and fully government-owned industry. Especially, up to the mid-1990s, mismanagement, poor monitoring and supervision, and higher political intervention made the sector underdeveloped (Ayalew and Zhang 2017, p. 6).

The newly replaced government in 1991 embarked on a new economic reform to replace centrally planned economic policy with a market-oriented system in 1994 and opened the banking industry to private domestic investors. The government has taken many structural measures to handle problems in the financial sector and to improve competition and efficiency. The newly introduced monetary and banking proclamation no. 83/1994 provides more autonomy to the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) and the industry is opened for domestic private investment (Ayalew and Zhang 2017, p. 6). In 1994, the first private commercial bank was licensed to operate in Ethiopia (Kannan and Sudalaimuthu 2016, p. 7). In 2021, the number of private commercial banks operating in Ethiopia reached 17, up from the only one in 1994 (NBE 2021, p. 69). Furthermore, following the new home-grown economic reform agenda, the government has opened the sector to full-fledged interest-free banks and allowed the foreign nationals of Ethiopian origin to own a share in Ethiopian banks and insurances. Accordingly, 14 banks joined the sector between 2020 and 2023, bringing the total number of commercial banks operating in Ethiopia to 31.

Even though the banking business has a long history in Ethiopia, it is still in its infancy, and its emerging intermediary sector and the financial system is underdeveloped (Fanta and Makina 2016, p. 152; Fanta 2016, p. 310). It is not yet competitive and efficient, nor is it capable of accelerating the economic growth of the country, which remains marginal (Dido 2020, p. 60). The Ethiopian population access to a bank is the lowest, even at sub-Saharan standards. The percentile of Ethiopian adults with an account is 35%, which is lower than the average percentile of the sub-Saharan region of 43% (Mengistu 2018, p. 1).

The structure of the Ethiopian financial sector shows that more than 76% of the sector’s asset is controlled by the three largest banks (NBE 2019). This higher degree of concentration indicates a lower degree of competition (Fanta and Makina 2016, p. 153). The performance of Ethiopian commercial banks is mainly determined by macroeconomic performance rather than competition (Guruswamy and Abdurkerm 2014, p. 20). Haile (2019, p. 51) also argued that macroeconomic factors are the key determinants of the financial performance of Ethiopian commercial banks. In general, the Ethiopian banking industry is characterised by less efficiency and little or insufficient competition (Ijara and Sharma 2020, p. 171; Dido 2020, p. 60).

Regulators are responsible for ensuring the existence of a strong risk management system and practices in banks to enhance reliance on the banking industry. The NBE has revised the Bank Risk Management Guidelines, which were established in 2003. In the revised guidelines, the NBE requires all banks operating in Ethiopia to establish a comprehensive risk management programme by focusing on credit, liquidity, market, and operational risks (NBE 2010). The large stock of provisions held by Ethiopian banks set aside for problem loans, which largely exceeds the provisions required for regular loans, confirms that credit risk has been a major concern of the Ethiopian banking industry (Lelissa 2014, p. 141). Over recent years, provisions for non-performing loans (NPLs) have consistently increased. Provisions held by Ethiopian commercial banks rose from 70% of NPLs in 2021 to 122.9% in 2022, and further climbed to 132.5% by the end of June 2023 (NBE 2024, p. 24). Furthermore, the NPL ratio of the banks increased consecutively from 2019 to 2022, rising from 2.3% to 3%, then to 3.5%, and finally to 3.9%. However, there was a declining trend in 2023, with the NPL ratio decreasing to 3.6%. Nevertheless, it is not only the result of poor credit risk management function; due to the interdependence of risks, other risk types could also contribute to the weakness of this function. It needs an integrated approach to risk management to handle all risks holistically encountered by the banks.

Ethiopia aims to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) by opening up the local market in all sectors for foreign investors, including foreign banks. At that juncture, stiff competition will ensue in the market between the existing banks and the new entrants. The competition is likely to be followed by the subsequent introduction of innovative products and operational and IT risks coming from the innovative products. If it is not managed effectively, it could adversely affect the operation and profitability of the overall Ethiopian banking sector. Establishing an effective ERM function is essential to compete and survive in the global market (Setapa et al. 2020, p. 498). The embedding of strong risk management systems will enable the banks to manage the aforementioned issues proactively. Therefore, there is a pressing need to assess the current ERM practices of Ethiopian commercial banks, pinpointing any gaps in the existing approach to ERM, in order to integrate a robust risk management system tailored to the Ethiopian banking sector.

Despite the growing literature on the issue of ERM in the financial sector, there is a lack of literature focusing on Ethiopia that examines the implementation of ERM in the Ethiopian banking industry. Only a few studies (Guruswamy and Abdurkerm 2014; Lelissa 2014; Gizaw et al. 2015; Asfaw and Veni 2015; Ademe 2015; Tade and Mebratu 2017; Pasha and Mintesinot 2017; Gugsa 2018; Tsige and Singla 2019; Alemu 2020) have examined the risk management function in the Ethiopian banking industry. Most of the prior studies focused on the traditional risk management (TRM) approach, the determinant factors of risk management, and its relationship with performance in the context of Ethiopian commercial banks.

From the above literature, only four studies (Ademe 2015; Gugsa 2018; Tsige and Singla 2019; Alemu 2020) have examined the ERM functions in Ethiopian financial institutions. The result of studies revealed the existence of weak ERM practices. However, the gaps in the ERM practices were not identified comprehensively, such as examining the risk assessment reports of the Ethiopian commercial banks.

2. Review of Relevant Literature

Doing business is compounded by uncertainties. These uncertainties might affect the main objectives of companies both positively and negatively (Shad et al. 2019, p. 415). Risk is a key concern for organisations when operating their businesses and the focus given to this issue has been increasing (ISO 2018, p. 1). Khan et al. (2016, p. 1886) suggested that, even if it is impossible to fully avoid risks, organisations should manage all types of risk they face. Historically, risk management was developed to cope with risks that arise in insurance companies and financial institutions, and it was known as traditional risk management (Shad et al. 2019, p. 416). Traditionally, the function of risk management was considered to protect an organisation from loss (Tuten 2018, p. 1). The approach and focus of silo-based risk management were limited to holistically managing interrelated risks, particularly in complex and global companies exposed to the financial crisis (Florio and Leoni 2017, p. 57).

The development of risk models and enterprise-wide approaches to risk management promotes the function of risk management to broaden enterprise wide, across all business lines and different types of risks (Bessis 2012, p. 43). A new concept named Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) was developed in 1990 to manage a group of risks around all business units using a holistic approach (Shad and Lai 2015, p. 1; Soomro and Lai 2017, p. 329; Braumann 2018, p. 241). This approach is a more integrated approach and involves assessment, quantification, and management of risks in the whole enterprise within all business functions and levels (Florio and Leoni 2017, pp. 57–58). There are various guiding principles for the conceivable adoption of an ERM programme that enable the evaluation of all material risks facing an organisation in a holistic approach. Due to the incorporation of risk management into corporate strategy, ERM should be a top-down process that the board of directors is responsible for (Bohnert et al. 2019, p. 236).

In an environment of increased risk complexities, the stakeholders of organisations need a risk management framework that promotes the benefits of efficiency, transparency, and solutions for interrelated risks. ERM can be used as a suitable tool to address these issues (Naik and Prasad 2021, p. 33). Employing ERM helps to confirm the soundness of reporting events and prevent risks to the reputation of the organisation (Heong et al. 2018, p. 84). Organisations that build a well-integrated ERM process into their strategic directions and day-to-day activities can exhibit a greater ability to handle risks within the whole organisation and, as a result, can improve their firm value (Prewett and Terry 2018, p. 17).

The amount of resources and time needed to respond to the risk and the inevitable crisis that might occur due to not implementing the ERM programme far outweigh those needed for prevention. The resources and time required to recover the losses resulting from public trust and confidence is enormous (Brandt 2018, p. 30). ERM plays a role in corporate governance by managing all corporate risks in an integrated manner and increasing the probability of attaining the strategic and operational objectives of organisations by supporting decision making (McShane 2018, p. 137). It is important to consider all risks that affect the firm’s performance to achieve the expected benefits of ERM and facilitate effective operational and strategic decision making (Lin et al. 2017, p. 346).

Banks are complicated financial firms engaging in intermediation activities with risks such as liquidity risk, credit risk, market risk, interest rate risk, systemic risk, operational risk, as well as performance risk (Udoka and Orok 2017, p. 69). Dabari et al. (2017, p. 4) also argued that the banking business is more complex and the measures to mitigate risk exposures have become crucial for their survival. The bankruptcy of large capital institutions following the large-scale financial crisis has severely impacted both the financial sector and the real economy (Kahramanoğlu and Koç 2016, p. 6). The global financial crisis of 2007–2008 was concluded by the collapse of major financial institutions (Udoka and Orok 2017, p. 69).

The banking sector in developing countries also has witnessed several causes of collapse, such as some banks from Nigeria and Kenya (Dabari et al. 2017, p. 5). The banking industry was primarily affected by these crises, and this situation has increased the interest of banks towards risk management (Kahramanoğlu and Koç, 2016, p. 6). The failures of risk management were mostly considered as one of the main reasons for the global financial crisis (Bates 2010, p. 23). The adoption of ERM in financial institutions needs to include four fundamental processes to make it integrated and holistic. This comprises the establishment of an ERM strategy, aligning the ERM strategy with a particular threat, identifying all risks facing financial institutions, building risk management infrastructure, and creating an ERM environment (Olayinka et al. 2017, p. 940).

Some researchers have investigated the implementation of ERM functions in financial institutions. Kahramanoğlu and Koç (2016, p. 6) studied the ERM practices in the Turkish banking sector, and the result of the study revealed that most of the banks have allocated budgets for the ERM function, which is an indicator of the banks’ concern with risk management. Similarly, Udoka and Orok (2017, p. 68) investigated the ERM practice in Nigerian banks and the study showed that there are different hindrances that highly affect the degree of acceptance and the level of ERM implementation in Nigerian banks. The government policies on ERM have a significant influence on the level of ERM implementation by Nigerian banks, and the acceptance and implementation of ERM have a positive influence on the performance of the banks. Beasley et al. (2005, pp. 521–22) examined the determinants of the stage of ERM implementation at various U.S. and international companies. The study revealed that the stage of ERM implementation is correlated with the type of industries, and it is positively related to the banking industry. Seik et al. (2011, p. 7) also investigated the effects of ERM programmes on publicly traded U.S. insurance companies during the financial turmoil. The result of their study revealed that all ERM programmes are not valuable but only well-designed once.

The recent regulatory developments following the financial crisis have increased the relevance of holistic ERM frameworks for financial institutions (Bohnert et al. 2019, p. 234). There are various factors that drive the implementation of ERM. Another strand of literature has identified several variables that are detrimental to the implementation of ERM. The increase in local and international regulatory pressures and internal organisational factors such as the availability of growth opportunities, poor earnings performance, and the anticipated likelihood of financial distress and its implicit and explicit costs make a significant contribution in moving organisations to adopt ERM (Khan et al. 2016, p. 1886). Arnold et al. (2015, p. 2) also noted that the shift of the risk management process from a rudimentary focus to a strategic approach is influenced by various factors involving current marketplace volatility, competition, globalisation, the level of stakeholder aversion to uncertainty, and compliance mandates. To implement the ERM system successfully, it is important to obtain strong support from the management, create risk awareness across the enterprise, and have the parties participate in the process (Oliveira et al. 2019, pp. 1015–16).

The study conducted by Yazid et al. (2012, p. 80) proposes seven factors that influence an organisation to adopt ERM: the appointment of a CRO, turnover, profitability, leverage, size, international diversification, and institutional ownership. On the other hand, Eckles et al. (2014, p. 247) argued that the adoption of ERM is related to diversification, institutional ownership, and stock volatility. Furthermore, Sprčić et al. (2015, p. 776) revealed that the maturity level of ERM implementation is mainly related to investment opportunities and firm size. Khan et al. (2016, p. 1887) also identified the variables that encourage organisations to put in place ERM as the risk management practice of the company, internal control, and external and internal drivers that force them to enhance the role of corporate governance.

Furthermore, Khan et al. (2016, pp. 1888–91) identified various factors that motivate organisations to implement ERM in a set of external factors and internal factors. The external factors generally comprise the increasing number of local and international regulations. It involves the guidelines and standards of organisations for employing and integrating their risk management practices. The major external factors that motivate organisations to implement ERM are industry consolidation and deregulation, globalisation, and technological progress that create better risk analysis and quantification. In addition, the major internal factors that influence companies to implement ERM are the possibility and the estimated costs of financial distress, the presence of growth prospects and high research and development levels, capital structure and market performance, and corporate governance-related factors.

The development and acceptance of ERM have arisen from a reaction to the speedy growth caused by globalisation and regulatory forces on firms to enhance their risk management practice in a holistic approach. In recent years, it has essentiality increased intensely due to continual financial scandals, corporate fraud, growing sophistication of risks and regulatory pressure (Shad et al. 2019, p. 415). Bohnert et al. (2019, p. 238) also documented the five firm characteristics that determine the ERM implementation of insurance companies as firm size, financial leverage, capital opacity, financial slack, and stock price and cash flow volatility.

The outcome of ERM depends on the maturity of its implementation. Organisations that engage in a mature ERM function realise higher operational performance than those that employ a less mature ERM function. Organisations that have a matured ERM function can achieve better performance (Mardessi and Arab 2018, p. 445; Farrell and Gallagher 2019, p. 616). The level of ERM implementation is influenced by different factors (Beasley et al. 2005, p. 521). Various types of ERM implementation stages are defined by different authors.

Yazid et al. (2011, p. 94) developed the level of ERM implementations into three stages: planning to adopt ERM, partial ERM implementers, and complete ERM in place. Similarly, Sprčić et al. (2015, p. 775) also published three ERM indices that help measure the maturity level of ERM development: ERM not developed, ERM moderately developed, and ERM highly developed.

Beasley et al. (2005, p. 527) also proposed five stages of ERM implementation: (1) no plans exist to implement ERM; (2) investigating ERM but no decision has been made yet; (3) planning to implement ERM; (4) partial ERM is in place, and (5) complete ERM is in place. Likewise, Beasley et al. (2015, p. 228) have identified five stages of ERM growth as very immature, developing, evolving, mature, and robust. Very immature firms have no plans to implement ERM and no ERM process is in place. Developing is when companies are presently studying the ERM concepts but have not yet decided to implement them. Evolving is when firms have no formal ERM process but plan to put one in place. Mature ERM is when organisations implement a partial ERM process but all risk areas are not addressed, and robust ERM is when organisations implement a complete formal ERM process. Based on the above two proposals, the first three steps are when organisations are not implementing the ERM process, and the last two steps are when companies are implementing the ERM processes.

Similar to the above developments, Oliva (2016, p. 66) proposed five maturity levels of ERM implementation: insufficient, contingency, structured, participative, and systemic ERM. Insufficient ERM is when firms with little understanding have no conceptual or physical structure dedicated to enterprise risks and no structured approach to adopting risk management practices. Contingency ERM includes organisations that have an awareness of risks that can affect them, and they roughly apply risk management methods, tools, and techniques. In the contingency stage, risk management is centralised, and the overall participation of employees is low. At the structured ERM stage, organisations have a greater level of process related to ERM and use more intense risk management methods, tools, and techniques. Participative ERM includes organisations that have a high awareness and structure about ERM processes and centralised risk management functions. This level of ERM is conducted with the involvement of most employees, and communication is a fundamental part of the risk management function.

Based on Oliva’s (2016, p. 78) explanation, the highest matured level of ERM is systemic ERM. At this level, organisations involve structured, conscious, and transparent ERM. To enhance their risk management, these organisations drew support from research institutions, partners, and consulting firms. Furthermore, their risk assessment function includes assessing the risk environments beyond their sovereignty.

Different from the above approaches, Ahmad et al. (2014, p. 544) identified six stages of the ERM implementation measurement instrument. The proposed stages are not considering ERM, rejecting the ERM concept, currently investigating the concept of ERM but have not made decisions yet, no formal ERM process in place but have plans to implement one, a partial ERM process in place, and a complete ERM process in place. The stages starting from one to four are taken as non-adopted, but stages five and six are considered as ERM adopters. Stage five shows partial employment of ERM, but stage six exhibits a complete ERM implementation.

In addition, Oliva (2016, p. 78) has proposed three parameters to assess the maturity level of ERM implementation. These are (1) the transparency in the communication of potential risks; (2) risk assessment in the environment of value; and (3) the participation of external agents in risk management. Ahmad et al. (2014, p. 545) noted that the integration of ERM with corporate strategy planning and decision-making processes demonstrates the full or complete implementation of ERM functions. Organisations with a medium degree of ERM maturity have an ERM function with a high level of structure and use techniques with a higher level of decentralisation (Oliva 2016, p. 78).

A well-designed ERM programme resulted in better performance, while weak ERM programmes are destructive since their implementation is incomplete and the overall programme is not integrated with the business strategic planning processes (Seik et al. 2011, p. 7). There is a higher gap between the current stage of ERM implementation and the expected future maturity level of banks ERM functions. This creates a higher need for ERM infrastructure to facilitate the enhancement of ERM capabilities over time (Dabari et al. 2017, p. 5). Implementing formal risk management policies and providing training on risk management for key business unit managers and senior executives promotes firms to establish a mature ERM function (Beasley et al. 2015, p. 221). Beasley et al. (2015, p. 221) also noted that more mature ERM functions might be developed by forming a management-level risk committee, including the senior executives that can deliver direction to business unit managers to assess the influence of risk events.

Despite the importance of risk management growing, there is a lack of information on the maturity level of ERM implementation in the banking sector, mainly in developing economies (Oyede et al. 2019, p. 2). Lundqvist and Vilhelmsson (2018, p. 127) examined the association between levels of ERM implementation and default risk with 78 of the world’s largest banks. The results of the study revealed that the maturity level of ERM implementation is adversely associated with the level of default risk. Seik et al. (2011, p. 7) also investigated the effects of ERM programmes on publicly traded U.S. insurance companies during the financial turmoil. The results of their study revealed that all ERM programmes are not valuable but only well designed once. Companies that established quality ERM programmes had higher profitability and lower stock volatility compared with weak-ERM performers and non-ERM peers. Dabari et al. (2017, p. 13) also examined the adoption of ERM in Nigerian banks, and the results of the study revealed that the Nigerien banks have a completely in-place ERM structure. The study also showed that human resource competency, internal audit effectiveness, and top management commitment also have a positive relationship with the maturity level of ERM in Nigerian banks.

The global financial crisis of 2008/09 exhibited that the risk management of various enterprises was weak. Consequently, financial regulators promote ERM to support the risk management of organisations and show that they are taking actions to enhance risk management. Following that, the ERM practice was expected to be widely initiated, implemented, and mature; nevertheless, the progress has been unsatisfactory. Some firms started and failed, some are still ready to try it, and several of those who begin are striving and undertaking only a few activities (Fraser and Simkins 2016, p. 690). Even implementing ERM has improved shareholders’ value with the adoption of a holistic risk management approach related to extensive costs. These include the hiring of CROs, instituting a board risk committee, building a risk culture all over the enterprise, and outspreading exertions about public relations. However, firms that implement ERM can improve their shareholders’ value since the benefits exceed the cost of ERM adoption (Bohnert et al. 2019, p. 237). Arnold et al. (2015, pp. 4–5) also noted that ERM is mostly troubled by a shortage of systems-level integration needed to obtain information simply and mitigate risks within the entire organisation. Without the integration of systems and data, the top management is not able to take a holistic view of risk management for risks faced by enterprises.

The regulatory bodies of various developed countries pressure institutions to enhance their risk management functions and risk disclosure practices. Some of the regulatory pressures are the UK Corporate Governance Code, the Dutch Corporate Governance Code, the NYSE Corporate Governance Rules, and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) in the U.S. These codes are practiced on publicly listed companies and request firms to establish an effective risk management system (Paape and Speklé 2012, p. 538).

The literature related to ERM has shown progress in developed economies; however, there is a remarkable lack of literature in developing economies that investigated the influence of ERM on the performance of financial institutions (Olayinka et al. 2017, p. 938). In recent years, various organisations from developing countries have begun to adopt a holistic and an integrated approach to risk management (Anton 2018, p. 151). ERM has a different influence on organisations from developing and developed countries due to the variation in financial systems and regulations (Chen et al. 2020, p. 10). The interest in studying risk management has shown a growing trend all over the world as a result of various economic conditions. These economic conditions have shown that the frequent global financial crisis underlined the essentials of the risk management function (Olayinka et al. 2017, p. 937).

The 2008 financial crisis, which overwhelmed the entire financial world, had a spillover influence on the financial systems of emerging economies. The regulatory institutions to safeguard the financial institutions have to ensure that all organisations in the institution implement ERM as soon as possible and carry out practices to confirm strict compliance with the ERM framework. The implementation of ERM in developing countries is also significantly associated with the financial performance of organisations similar to those in developed economies (Olayinka et al. 2017, pp. 937–38).

In the process of financial intermediation, banks are exposed to financial and non-financial risks. These risks are interrelated, and the risk occurrence in either area can influence the magnitude of other risks (Attarwala and Balasubramaniam 2015, p. 10). The three major risks that face all banks are credit risk, liquidity risk, and operational risk (Elbadry 2018, p. 123). The types of risks to which organisations are exposed can be classified as financial and operational risks (Bessis 2012, pp. 26–27; Attarwala and Balasubramaniam 2015, p. 10). The financial risks consist of liquidity risk, credit risk, mismatch risk, foreign exchange risk, interest rate risk, and solvency risk. However, risks can also be classified as hazard, financial, operational, and strategic risks (McShane 2018, p. 137).

In less monetised countries such as Ethiopia, banks dominate the financial sector. The major financial institutions in Ethiopia are banks, contributing significantly to the economic growth and development of the country (Tade and Mebratu 2017, p. 47). In Ethiopia, commercial banks are playing a fundamental role as financial intermediaries for the economic growth and development of the country by transferring idle funds from depositors to borrowers for investment (Kossa and Pasha 2016, p. 89). The status of risk management practices in Ethiopian banks showed that risk management programmes and strategies are not documented as required and risk management documents are not reviewed regularly.

Ademe (2015) has investigated ERM practices in Ethiopian private banks. The study revealed that the ERM practice of Ethiopian banks is in the infant stage. In addition, most Ethiopian banks either do not establish the risk management programme needed by NBE at all or fail to establish a comprehensive risk management programme. Alemu (2020) also examined the ERM function in Ethiopian banks. The study found that almost all Ethiopian commercial banks do not have adequate awareness of enterprise level risk management practices. The study also found that the major challenges facing banks to manage their enterprise-level risks are a weak tone at the top and less attention from top management, the absence of workable environments, the absence of qualified staff, and the absence of advanced risk management software. The study conducted by Tsige and Singla (2019, p. 5289) also revealed that the implementation of ERM in Ethiopian financial institutions is low and it is in the infant stage and these financial institutions have a less developed ERM practice compared with the international organisations.

3. Research Methodology

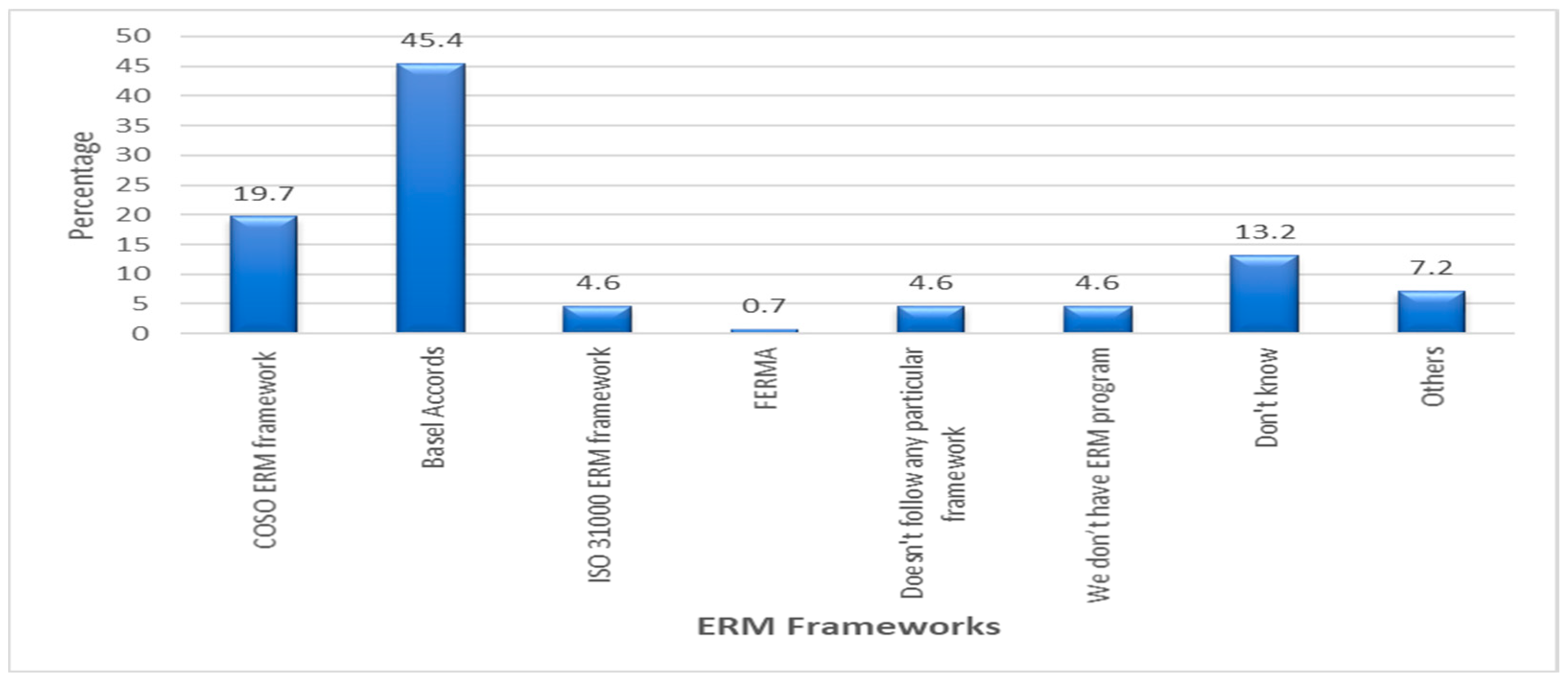

The objective of this study is to examine the ERM practices of Ethiopian commercial banks. To achieve this objective, the study adopted a mixed-methods research design consisting of qualitative and quantitative research designs. The qualitative research design was a content analysis of risk assessment reports of Ethiopian commercial banks and ERM standards. The target population for the content analysis was all Ethiopian commercial banks established before 2021. The number of commercial banks operating in Ethiopia during the 2021 year was 17 (NBE 2021, p. 68). Of the seventeen Ethiopian commercial banks, four banks granted the researcher permission to access their yearend risk assessment report for the purpose of the study. Convenience sampling is a type of non-probability sampling, where the target population members that meet definite measures, such as easy accessibility, geographical proximity, availability at a given time, or the willingness to participate, are incorporated for the objective of the study (Etikan et al. 2016, p. 2). Accordingly, convenience sampling was adopted to select the samples for the content analysis.

Sample banks for the content analysis were selected based on their convenience or willingness to allow the use of their risk assessment reports for research purposes, and the year-end risk assessment reports of sample commercial banks were collected and analysed. The year-end risk assessment reports for the fiscal year 2020/21 of the sample Ethiopian commercial banks, NBE Risk Management Guidelines, and ISO:31000 and COSO ERM frameworks were collected for the study. The annual risk assessment reports of the sample banks were analysed to check their compliance with NBE requirements and other internationally acceptable guidelines, such as ISO:31000 and COSO ERM frameworks. The data were analysed using Atlas-ti software, and themes were developed by employing thematic analysis.

The second phase of the study was a collection of quantitative data using a survey. Following the content analysis, it was important to examine the maturity of the current approach to ERM in Ethiopian banks and related gaps. These could be addressed by developing a questionnaire and distributing it to the risk management experts who are familiar with the risk management functions of Ethiopian commercial banks. Hence, a survey study was employed in the second phase, and the questionnaire was administered to risk managers and risk management officers of Ethiopian commercial banks. The questionnaire that was developed for this study was distributed to respondents through email. The quantitative data were collected from risk managers and risk management officers. The results of the descriptive statistics analysis of the survey study were used to examine the current practice of ERM in Ethiopian commercial banks. The online survey was distributed to 181 respondents through LimeSurvey. Out of the total 181 target potential respondents, 152 respondents fully completed the online survey, which gives an 84% response rate to the survey.

The researcher applied various methods to ensure the internal and external validity of the result of the survey study. The questionnaire was pre-tested to ensure its validity and reliability. The pre-test was conducted with the risk manager and risk management officers of the Bank of Abyssinia. Eight experts participated in the pilot survey of the study. Since one of the researchers was an employee of the Bank of Abyssinia, the bank’s employees were excluded from the main survey but participated in the pre-test of the questionnaire.

The content validity of the research was tested by a risk management expert, who was a chairman of the “Risk Management Association of Ethiopian Banks”, and two academicians, who are also the chairman and members of Board Risk Management Committees in Ethiopian commercial banks. These three experts reviewed the questionnaire, identifying and eliminating redundant, technical/non-user-oriented items, and less relevant items, and their feedback used to revise the questionnaire. The face validity of the study was tested to ensure a logical link between the questions included in the questionnaire and the objective of the study. One of the researchers, who also supervised the study, evaluated this aspect, and relevant revisions were made based on the feedback of the supervisor.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the research findings of the study, divided into two sub-sections. First, the results of the content analysis are discussed. Then, the results of the survey study are presented.

4.1. Content Analysis

The purpose of the content analysis was to develop two groups of themes: one from ERM standards and another from the risk assessment reports of Ethiopian commercial banks. From the ERM standards, including the NBE risk management guidelines, as well as the COSO and ISO ERM frameworks, a total of 460 codes were developed. These codes were organised into 108 sub-groups and summarised into 30 overarching themes, which were then grouped under seven distinct ERM pillars or factors.

Conversely, through the content analysis of the risk assessment reports of Ethiopian commercial banks, 190 codes were produced, which were categorised into 59 sub-groups and ultimately summarised into 27 themes (see Appendix A). These themes were subsequently aligned with the seven ERM pillars, consistent with the structure derived from the ERM frameworks and guidelines. Finally, a comparative analysis was conducted between the themes derived from the Ethiopian commercial banks’ reports and those extracted from the standards. Through this comparison, gaps in the risk management practices of Ethiopian commercial banks were identified, providing valuable insights for enhancing their ERM frameworks.

4.1.1. Vision, Mission, Core Values, and Strategy

From the thematic analysis of ERM standards and Ethiopian banks’ risk assessment reports, several key themes pertaining to vision, mission, core values, and strategy were developed. From the ERM standards, the identified themes were vision, mission, and core values; strategy; and business objectives. Similarly, the analysis of the banks’ risk assessment reports yielded three themes: vision, strategy, and business objectives.

The themes of vision, mission, and core values were identified from the ERM standards. A parallel theme, vision, was also developed from the thematic analysis of risk assessment reports. The themes explained that the banks’ risk management function did not originate from their mission and core values. The reports did not evaluate the alignment of risk management practices with the mission and core values of the banks. In addition, the risk assessment reports failed to assess the integration of the risk management function with their mission and core values.

A theme strategy was developed from the thematic analysis of both the ERM standards and the risk assessment report of the banks. A comparison of the descriptions of this theme from the two sources revealed that the risks to achieving the banks’ strategies were identified and the realisation of strategic targets, particularly in terms of financial performance and asset quality level, was addressed in the risk assessment report of the banks. Most of the banks have initiated strategic plans to achieve their vision and mission. However, there was a bank which has no strategic plan during the reviewed period, the previous five-year strategic plan had expired and a new one had not been finalised. Furthermore, the alignment of risk management function with their strategies was not assessed, and potential risks considered during strategy setting were not identified and evaluated by the banks.

The third theme developed through the thematic analysis of both ERM standards and the risk assessment reports was business objectives. This theme elucidated that the banks’ risk management function evaluated the achievement of targets and business objectives, particularly in terms of financial performance and asset quality. Risks to attaining these business objectives were identified. However, their risk management function did not assess risks during setting business objectives.

4.1.2. Risk Management Environment

The second group of themes, developed from the thematic analysis of both ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports, pertains to the risk management environment. Themes derived from ERM standards included internal and external context, governance and culture, board risk oversight roles, and management risk management roles. Similarly, four themes were identified from the banks’ risk assessment reports, namely internal and external context, culture, board risk oversight roles, and management risk management roles.

The theme of internal and external context, developed from the analysis of both sets of documents, illustrates that Ethiopian commercial banks have been assessed regarding the internal and external factors that could confront their strategy execution and organisational performance.

The theme of governance and culture was identified during the thematic analysis of ERM standards. From the thematic analysis of the banks’ risk assessment report, a related theme, culture, was developed, which corresponded to the theme of governance and culture established by ERM standards. These themes demonstrated that Ethiopian commercial banks were committed to prompting a sound business environment through robust risk management practices and enhancing risk culture across the enterprise, with the ultimate goal of maintaining risks at an acceptable level by minimizing losses and strengthening control mechanisms. However, the governance issue was not addressed in the banks’ risk assessment report.

The theme of board risk oversight roles was developed from the thematic analysis of both ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports. The theme showed that the factors that could expose the banks to various risks and the issues that require the attention of the board were assessed and reports were delivered to the board of directors. The boards had drawn notation, deliberation and correction actions on the issues and concerns with regard to specific cases and overall practices, compliance and ethical considerations. The banks’ risk assessment reports provided relevant information to decision makers to make informed decisions and realise their objectives. The reports supported the boards to ensure the effectiveness of the risk management practice throughout the banks, and to bring areas of concern that require the attention of the board. However, the risk oversight role of the boards was not strong enough to enable the banks to comply with the regulatory and internal risk exposure limits, since the banks failed to comply with various regulatory and internal limits.

The last theme that was developed that related to the risk management environment through both thematic analysis of ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports was management of risk management roles. The theme argued that events that could expose the banks to various risks and that needed the attention of the senior management were assessed and the reports were delivered to the management. The reports also revealed that there were submissions of incident reports, but there is still a lot to be done by the management to set the right tone at the top to emphasise the strict fill-out and dispatch of incident reports by all concerned personnel. In addition, from the sample of four banks, only one bank assigned a CRO at the executive management level for its risk management function, even though assigning a CRO is one of the proxies of implementing the ERM function in an organisation. For the remaining three banks, their risk management functions were managed by risk and compliance Directors.

4.1.3. Risk Management Tools

From the thematic analysis of both ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports, themes related to risk management tools were developed. Four themes, namely resources for risk management, risk management policies and procedures, risk exposure limits, and clearly defined risk management authority, were identified from the ERM standards. Furthermore, three themes related to risk management tools, namely risk management policies and procedures, risk exposure limits, and clearly defined risk management authority, were developed from the risk assessment reports.

The theme of resources for risk management was developed from the ERM standards. However, no theme related to resources for risk management was developed from the banks’ risk assessment reports. Consequently, this illustrates that the risk assessment reports of Ethiopian banks did not evaluate the resources needed to manage risk or support the prioritisation of resource deployment for risk management. The reports did not assess the adequacy of the human and physical resources allocated to risk management.

From the thematic analysis of both sets of documents, the theme of risk management policies and procedures was developed. This theme describes that Ethiopian commercial banks have established policies and procedures to manage risks and ensure compliance with relevant laws and regulations. The reports also indicate that one of the four banks revised its procedures during the period under review.

The theme of risk exposure limits was established in both the ERM standards and the banks’ assessment reports. These themes show that the banks have set various risk exposure limits, including one of the four banks established a zero-fraud tolerance limit as an operational risk exposure limit. However, this operational risk exposure limit was set only for fraud, and there were no exposure limits established for other risks such as IT risk, legal risk, reputational risk, strategic risk, and regulatory risks. Furthermore, there was no credit concentration limit set for sub-sector loans within domestic and trade sector loans.

The last theme that was developed related to risk management tools through thematic analysis of the ERM standards was clearly defined risk management authority. Similarly, the theme of risk management authority was also developed during the thematic analysis of the banks’ risk assessment reports. These themes highlighted that there was a lack of understanding among staff regarding their risk management authority. The risk assessment reports recommended that the banks enhance the awareness among frontline staff regarding internal control by assigning responsibility and accountability and communicating pertinent procedures and circulars from top frontline staff. The recommendation also suggested that the banks provide adequate training to new hires and refresh other relevant staff members to ensure a thorough understanding of the bank’s procedures and adherence to them.

4.1.4. Risk Management Function

From the thematic analysis, five themes related to risk management function were identified from the ERM standards, and four themes were identified from the banks’ reports. The themes developed from ERM standards were independent risk function, internal audit of risk management activities, internal control, management information system (MIS), and ERM framework. Furthermore, independent risk function, internal audit of risk management activities, internal control, and ERM framework were the themes developed from the banks’ risk assessment reports.

The theme of independent risk function was developed both from the thematic analysis of ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports. The theme explained that the Ethiopian commercial banks have delivered their risk assessment reports directly to the board risk committees. The NBE, under its corporate governance directive number SBB/71/2019, requested that the board risk committee of every Ethiopian commercial bank hold regular meetings, at least once every month, and report regularly to the full board. To undertake this responsibility, the board risk committee of each bank is expected to receive a periodic risk assessment report from the Risk and Compliance Management Department. The Ethiopian commercial banks had established an independent risk function and the functions had delivered their reports directly to the board risk committee and full board.

From both the thematic analysis of ERM standards and the banks’ reports, the theme of internal control was developed. The theme highlighted that the banks set policies, procedures, and limits as an internal control tool. However, potential areas of conflict of interest were not identified and reviewed by internal control and risk management functions.

The theme of internal audit of risk management activities was also developed from the thematic analysis of the ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports. The theme explained that the internal audit function of Ethiopian commercial banks covered some branches and selected a few head office organs of the banks. Hence, the audit function did not cover all activities and functional areas of the banks, including risk management processes and practices.

The theme of MIS was developed from the thematic analysis of ERM standards. However, there was no theme derived from the banks’ risk assessment reports related to MIS and the risk assessment reports of the banks revealed that information used for the risk analysis was collected from different functions of the banks, such as audit, portfolio management, finance and accounting, treasury management, trade finance, and branch operations. There was no structured MIS on the banks that deliver all relevant information to their risk management department and track changes on risk exposure of the banks, and compare the current risk exposure with policy limits and past forecasts.

The last theme developed which related to risk management function from the thematic analysis of ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports was the ERM framework. The theme revealed that the sample banks have a risk management programme, and among the four banks, one has developed operational risk management framework and risk vulnerability assessment of two business units was conducted based on the framework. However, the banks have no comprehensive ERM framework and a framework was only prepared for operational risk in one of the four banks. More importantly, the banks failed to establish an IT risk management framework to manage risks related to the current evolving technological changes and digitalisation era.

4.1.5. Risk Management Process

From the thematic analysis of the ERM standards, 164 codes that were summarised into the following six themes: risk identification, risk measurement, risk controlling, risk monitoring, information, communication and reporting, and regular review and revision, related to risk management processes, were established from the ERM standards. Similarly, from the thematic analysis of Ethiopian banks’ risk assessment reports, 94 codes which were related to the risk management processes were identified. Likewise, the result of the thematic analysis of ERM standards, the codes were summarised under six themes.

Risk identification was the first theme that related to risk management process and identified both from the ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports. The theme explained that the Ethiopian commercial banks have identified various risks. The risk assessment reports assessed the interdependency between rescheduled loans, which are linked to credit risk, and the stability of the banks’ liquidity position, asset quality, and earnings. The reports revealed that external fraud incidents have been increasing recently, and debit card fraud cases were also on the rise from time to time, both of which pose reputational risks to the banks. The risk assessment reports also indicated the existence of failures to appropriately manage the source of operational risks. The banks have identified some common risk indicators for operational risk monitoring purposes. In addition, based on credit risk indicators, credit-related risks were identified by the banks. However, risks in all functional areas such as purchasing, facility management, building construction, and security and activities such as interest-free banking products and activities were not covered by the banks. In addition, the relationship between all relevant risks and the impact of one risk on other risks was not assessed in all risk types.

The second theme established from both sets of documents and related to risk management processes was risk measurement. The theme explained that Ethiopian commercial banks have been measuring various risks. The banks used various risk measurement tools, such as stress testing, scenario analysis, and gap analysis. The banks measured their capital adequacy to absorb losses by using the capital adequacy ratio. They also computed their average loan recovery rate to determine their credit risk exposure level. The banks conducted risk forecasting of various risk by using different techniques. In addition, one of the four banks prepared a risk register to measure its exposure to operational risk. However, not all banks prepared operational risk registers. Furthermore, the level of operational risk was not measured. In addition, IT risks and reputational risks were not included in the banks’ risk measurement systems.

Risk controlling was the first theme that related to the risk management process and identified both from the ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports. The theme explained that the banks conducted controlling activities over compliance risk, credit risk, FOREX risk, interest rate risk (IRR), IT risk, liquidity risk, off-balance-sheet risk, operational risk, regulatory risk, and strategic risk. The banks underwent a review of the collateral taken and measured their collateral adequacy ratio to assess the strength of their credit risk mitigating tools. The banks also held provisions for loss loans to absorb losses related to defaulted loans.

The theme of risk monitoring was also developed from the thematic analysis of the two groups of documents. This theme explained that the banks conducted risk monitoring activities over compliance risk, credit risk, FOREX risk, IRR, liquidity risk, off-balance-sheet risk, operational risk, regulatory risk, and strategic risk. However, the effect of each controlling activity on reducing the risk exposure levels of the respective risks was not assessed by the banks’ risk monitoring activities.

The thematic analysis of both the ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports have developed the theme of information, communication, and reporting. The theme explained that the Ethiopian commercial banks reported and communicated the exposure levels of compliance risk, credit risk, FOREX risk, legal risk, liquidity risk, market risk, operational risk, strategic risk, and IR risk. The report of one of the banks showed that its strategy was communicated to the staff and work units and its corporate strategy has been cascaded to the respective work units and corresponding personnel. The incident reports were collected only from a few functional areas. Audit reports resulting from audits conducted on various work units were received and considered as an input for the risk assessment reports.

The theme of regular review and revision was established based on the thematic analysis of both the ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports. The theme explained that the banks have periodically reviewed their risks using different acceptable techniques. The banks reviewed their guidelines and risk exposure limits for various activities. The reports also recommended a review and reconsideration of risk exposure limits in various activities, such as loan portfolio exposure by sector and credit products, time deposit ratio, FOREX asset to total asset ratio, and FOREX deposit to liquid asset ratio.

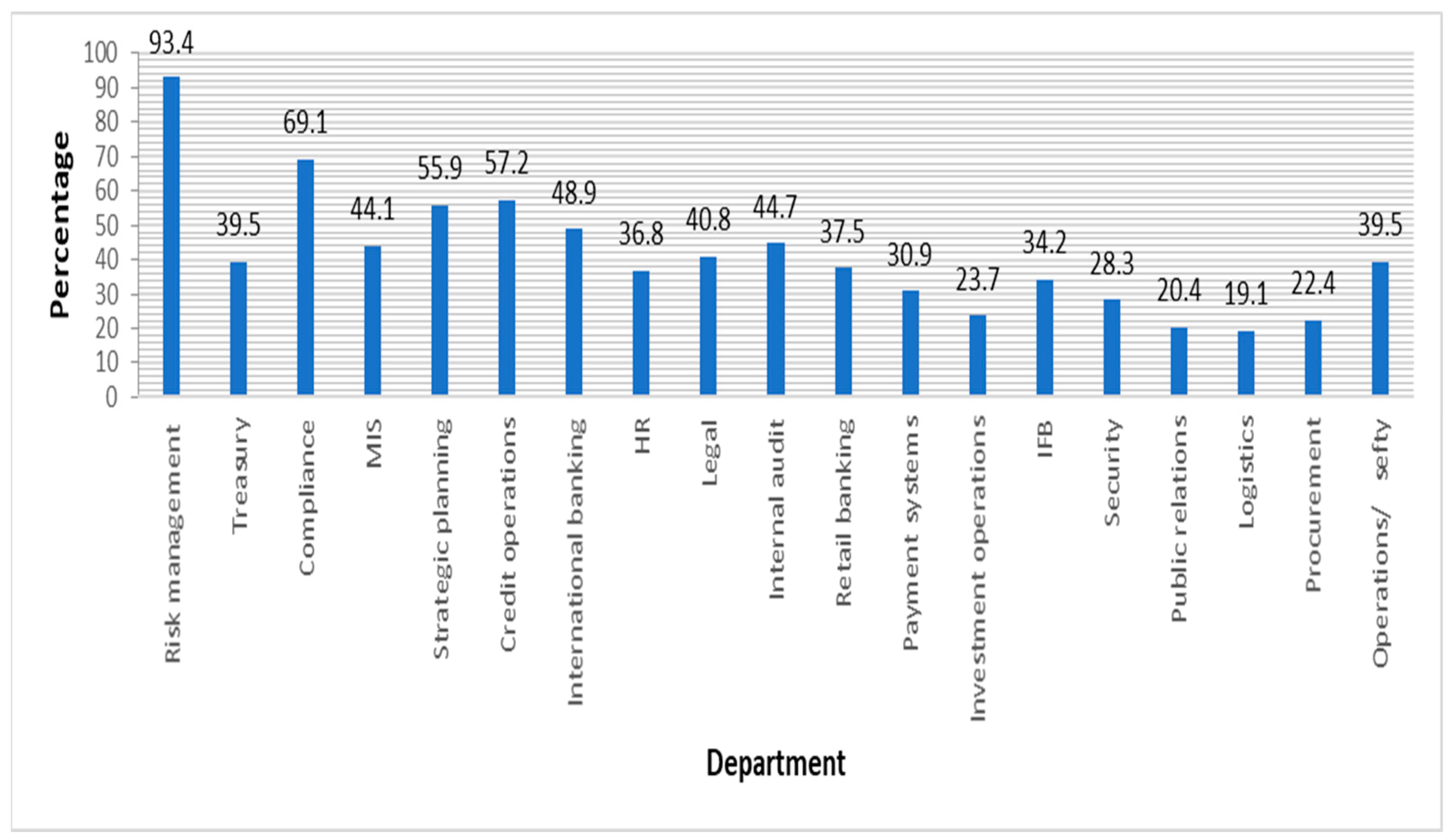

4.1.6. Comprehensiveness, Integration and Alignment

The other groups of themes developed from the ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports were related to comprehensiveness, integration, and alignment. The themes developed from the ERM standards were the comprehensiveness of the risk management function, integration of risk management activities, and alignment of risk management with strategy and performance. Likewise, 28 codes developed from the banks’ risk assessment reports were summarised under two themes: comprehensive risk management function and alignment of risk management with vision and strategy.

The theme of comprehensiveness of the risk management function was identified during the thematic analysis of both ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports. The theme discussed was that most relevant risks such as credit risk, market risk, FOREX risk, IRR, operational risk, IT risk, regulatory risk, reputational risk, and legal risk were identified and assessed by the Ethiopian commercial banks. In addition, events that could be the source of various risks such as system failure, FOREX rate movement, FOREX off-balance sheet commitment, fraud and fraud attempts, control systems, human resources, and IT were assessed by the banks. However, their risk management function did not cover all risks, such as systemic risks and cyber security risks.

The theme of integration of risk management activities was developed from the thematic analysis of ERM standards. However, no theme related to the integration of risk management activities was identified from the thematic analysis of risk management reports. The Ethiopian commercial banks had been assessed for risks in some functional areas such as finance and accounting, credit business, branch banking operations, e-banking, IS, and trade finance departments. However, the risk management function was not integrated into all functional areas, and activities and functional areas such as management information systems (MISs), IT security, marketing, strategy planning, and purchasing were not covered by the risk assessment report. In addition, risks that arise in one functional area and have an impact on other functional areas were not analysed. The reports also did not review the integration of their risk management activities with strategy and performance.

The theme of alignment of risk management, strategy, and performance was established from the thematic analysis of ERM standards; likewise, the theme of alignment of risk management with vision and strategy was developed from the thematic analysis of the risk assessment reports of the banks. The theme illustrated that risk management was set as one of the strategic objectives in a commercial bank taken as a sample. However, the thematic analysis of the study showed that the banks did not evaluate the alignment of their risk management activities with organisational vision and strategy.

4.1.7. Enhanced Value

The last groups of themes developed from the thematic analysis of the ERM standards and the banks’ risk assessment reports were related to enhanced value. The five themes developed from the ERM standards were informed decision making, respond to change, performance improvement, compliance, and value creation. Fifteen codes that related to the impact of risk management on firms’ value enhancement were also developed from the thematic analysis of the banks’ reports. The codes were summarised under five themes as the themes developed from the ERM standards.

The descriptions of the theme of informed decision making revealed that the Ethiopian banks risk assessment reports provided information for decision makers of the banks, mainly the board and senior management, towards the achievement of organisational objectives. The reports also measured the effectiveness of risk management practices throughout the banks and brought up areas of concern that required the attention of the board and senior management. The reports also provided recommendations on risks and opportunities and potential decisions that could be taken to manage the risk and utilise the opportunities.

The comparison of the respond to change theme identified from the two sets of documents highlighted that the Ethiopian commercial banks had established contingency plans for liquidity risks to deal with unexpected liquidity situations. However, the result of the study revealed that banks had not taken proactive measures for the adverse effects of COVID-19 and the influence of the current political and economic instability of the country. Moreover, the banks have not prepared contingency plans for risks other than liquidity risks, such as operational risk.

The theme of performance improvement developed both from the ERM standards and the banks’ reports showed how the risk management function of Ethiopian commercial banks supported them in achieving their financial performance. Their risk management function provided feedback on the measures that could be taken to enhance their performance. The overall financial performance of Ethiopian commercial banks was above their budget in terms of earnings and profit. The banks achieved most of their performance targets and objectives. However, the banks failed to achieve some performance targets, such as capital adequacy ratio, loan-to-deposit ratio, expense, interest income, effective IR and cost of funds, interest expense, revaluation loss, and branch opening targets.

The theme of compliance was developed from the thematic analysis of the two groups of documents. These themes explained that the Ethiopian commercial banks have complied with the majority of the internal and regulatory limits. However, the result of the study revealed that the banks failed to comply with various internal risk exposure limits, the standards set on KYC during account opening, and discrepancies were observed on banks complying with internal policies and procedures. Moreover, the banks complied with most of the NBE directives, but they failed to comply with NBE directives, in terms of credit concentration limits on the NPL level and their sectoral concentration, FOREX risk limits on the FOREX open position, and operational risk regulations related to account opening, set by the NBE customer due diligence directive and the Ethiopian Financial Intelligence Center (EFIC) KYC directive. The banks delivered an adequate report to EFIC on cash transactions, non-cash transactions, and suspicious transactions. They also provided training on AML/CFT for their staff in accordance with EFIC requirements.

The last theme identified from the thematic analysis of ERM standards and the banks’ reports was value creation. The theme explained that the ERM function of Ethiopian commercial banks was mainly focused on ensuring compliance with regulatory directives, reporting, and their own policies and risk-exposure limits. The banks have not been taking proactive measures for adverse changes. Even though the banks can achieve the target, the ERM function could go further to create value and to utilise the opportunities.

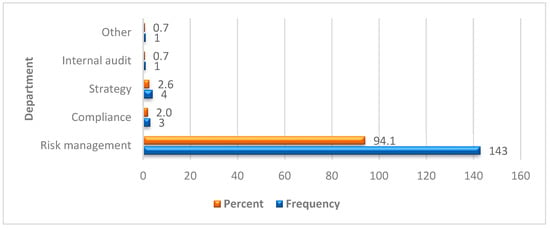

4.2. Survey Study

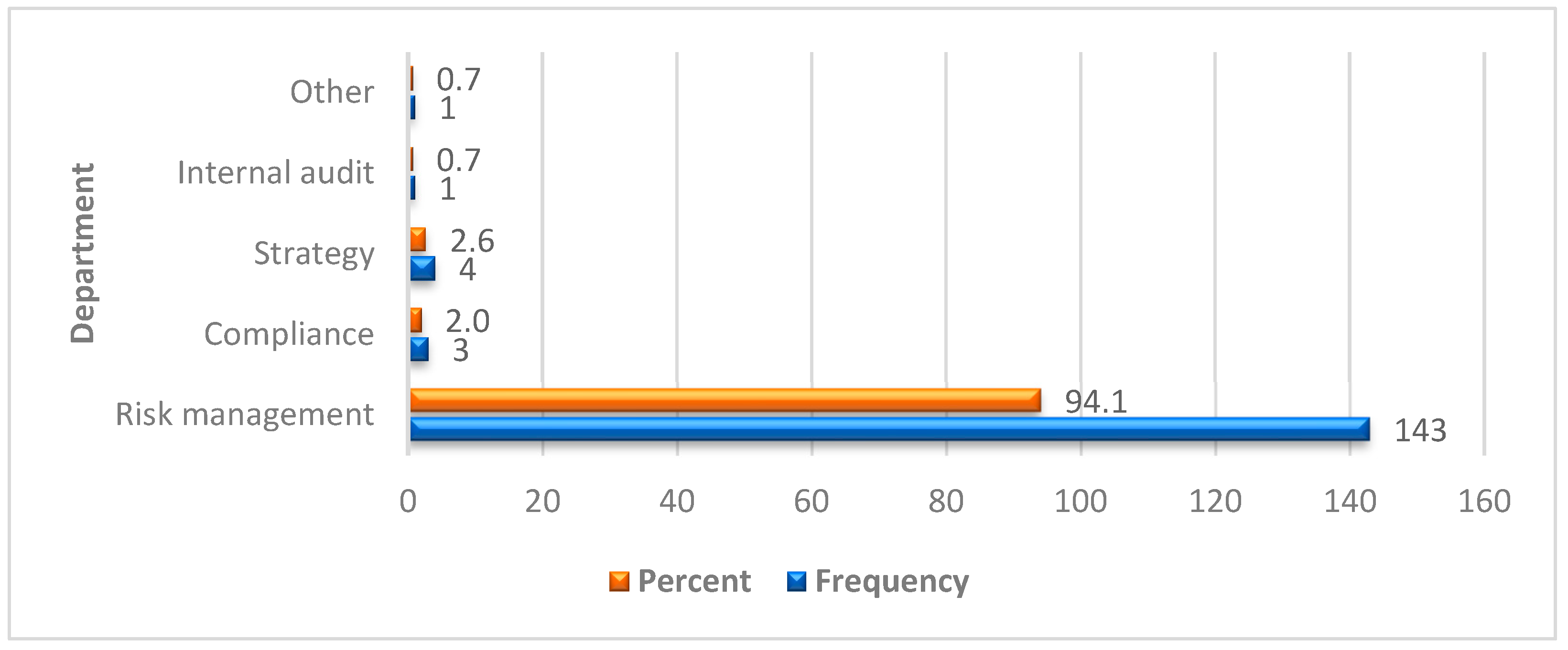

The questionnaire was distributed to all risk managers and risk management officers across all Ethiopian commercial banks except the Bank of Abyssinia. The online survey was distributed to 181 respondents through a lime survey. Out of the total 181 target potential respondents, 152 respondents fully completed the online survey, which gives an 84% response rate to the survey.

4.2.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

In total, 152 respondents who have experience in risk management in Ethiopian banks participated in the study. Table 1 presents a summary of demographic characteristics of the survey participants such as current position, educational status, and work experience.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents.

The job positions of the respondents, as illustrated in Table 1, indicate that the largest share of respondents (42.8%) were senior risk management officers, followed by risk management officers (22.4%). The risk managers comprised 21.7% of the respondents, and 9.2% were principal risk management officers. The remaining 3.9% of respondents were junior risk management officers. This indicates that most of the respondents (73.7%) had senior risk expertise experience; they were senior risk officers, principal risk officers, and risk managers. This finding highlighted that the majority of the respondents have an adequate understanding of ERM and its practices in Ethiopian commercial banks.

The educational background of the respondents established that most of the respondents (65.8%) had a second degree, followed by 33.6% of first-degree holders. The remaining one respondent (0.7%) had a doctorate degree. This indicates that all of the respondents have a minimum of a bachelor’s degree and most of the respondents have a master’s degree. This highlighted that all of the respondents had a minimum first degree, which indicated that the respondents were educated and knowledgeable. In addition, it could be considered that the respondents understand the questionnaire that was distributed with regard to ERM and are capable of giving relevant responses based on their knowledge. The presence of skilled and qualified employees is essential to embedding a structured approach to ERM in Ethiopian commercial banks. Furthermore, the study revealed that the risk management functions of Ethiopian commercial banks were dominated by a literate group of personnel.

The banking experience of the respondents revealed that the majority of the respondents (40.8%) had 6 to 10 years of experience, followed by 25% with 11 to 15 years, 17.1% with 2 to 5 years, and 14.5% with over 15 years. The remaining 2.6% had less than 2 years of banking experience. This indicates that most of the respondents (80.3%) had above 5 years of experience, and almost all of the respondents (97.4%) had more than 2 years of banking experience. The study established that most of the respondents had adequate experience in the operations of Ethiopian commercial banks. This finding highlighted that the majority of the respondents had an adequate understanding of the Ethiopian banking industry and the risk management environment and practices of the industry. It could be deduced that the employees had adequate knowledge of the industry to establish an appropriate risk management function in banks. In addition, their adequate banking experience could help to identify all risk exposures in all functional areas of the banks, and it is fundamental to establish an effective risk management function in banks.

The risk management experience of respondents showed that the highest percentage of participants had less than 2 years of experience in the risk management function (36.2%), followed by 2 to 5 years of experience (34.9%). Moreover, 24.3% of the participants had between 6 and 10 years of experience in the risk management function, and the remaining 4.6% of the participants had 11 to 15 years of experience in the risk management function. This indicates that most of the respondents (63.8%) had over 2 years of experience in risk management functions. The study established that the respondents have an adequate understanding of the risk management function of Ethiopian commercial banks and are proficient enough to participate in the study.

Overall, the demographic information of the respondents revealed that the risk management function of the Ethiopian commercial banks was dominated by senior risk management experts. In addition, the risk management employees of Ethiopian commercial banks had adequate experience in the banking sector and risk management functional areas. Furthermore, most of the risk management employees had second degrees. This highlighted that the risk management functions of the banks were dominated by skilled personnel.

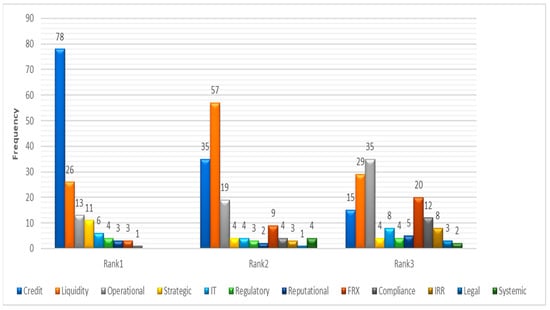

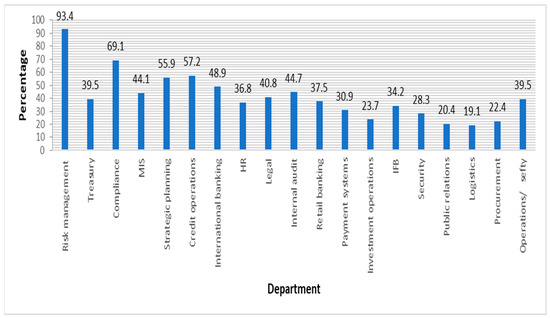

4.2.2. ERM Practices of Ethiopian Commercial Banks

The second part of the survey study was intended to investigate the ERM practices of Ethiopian commercial banks. The current approach and practices of ERM in the Ethiopian banking context are described in this section.

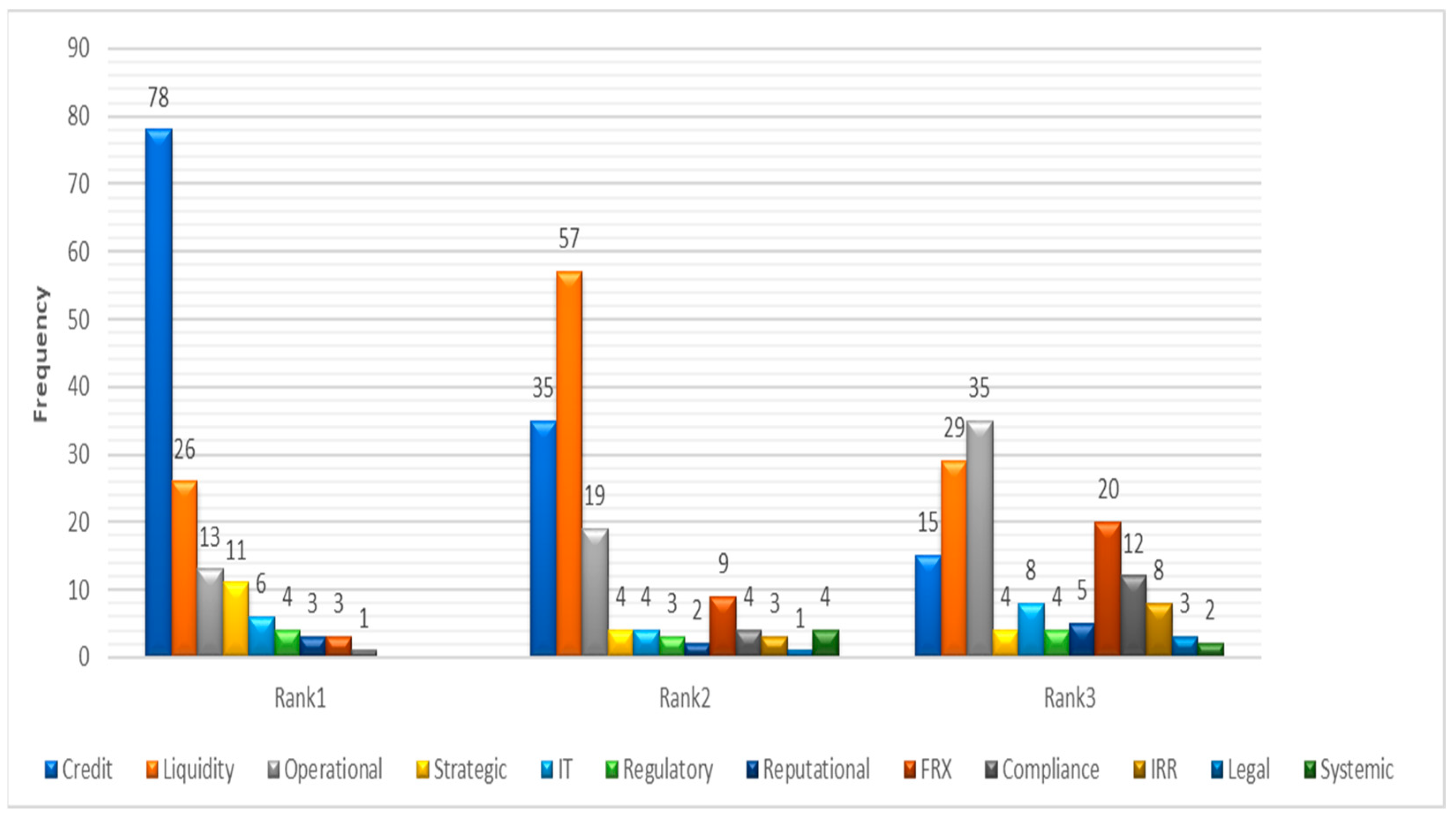

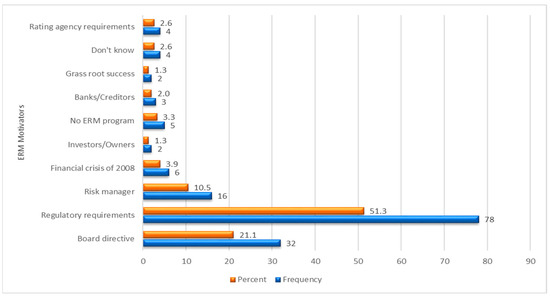

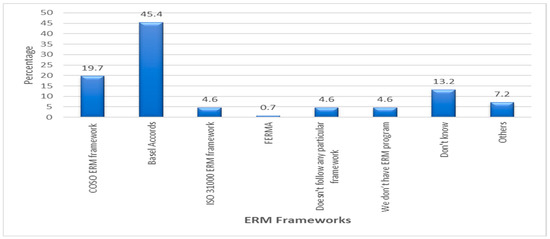

Responsible for the Review and Approval of Risk Management Policies and Guidelines

The revised Bank Risk Management Guidelines prepared by NBE (2010) indicated that the board of directors is responsible for reviewing and approving a bank’s risk management strategies and policies. In addition, the COSO ERM framework (COSO 2017, p. 2) sets the oversight role of the board of directors as reviewing, challenging, and concurring with management on proposed strategies and risk appetites. Respondents were asked to determine the responsibilities of different bodies of their banks regarding ERM practices. Figure 1 depicts the result of the body responsible for the review and approval of risk management policies and guidelines.

Figure 1.

Party responsible for approval of risk management policies and procedures.

Consistent with established standards, the result of the study indicated that the risk management policies and guidelines of Ethiopian commercial banks were mainly approved by the board of directors (82.9%). The remaining 6.6%, 4.6%, and 4.6% of the banks’ risk management policies and guidelines were approved by the CEO, executive management, and risk management department, respectively. This indicated that most of the policies and procedures were approved by the board of directors in line with the NBE guidelines and COSO ERM framework. Therefore, the mandate of reviewing and approving risk management policies and procedures was given to the right body in the targeted banks. Considering that all risk management policies and procedures are expected to be approved by the board of directors, the remaining 17.1% of the banks’ risk management policies and procedures should ideally also be approved by the board. This would establish the right tone at the top, promote accountability, maintain governance standards, ensure regulatory compliance, and align risk management with the overall strategy, thereby ensuring a sound risk management system in the banks.

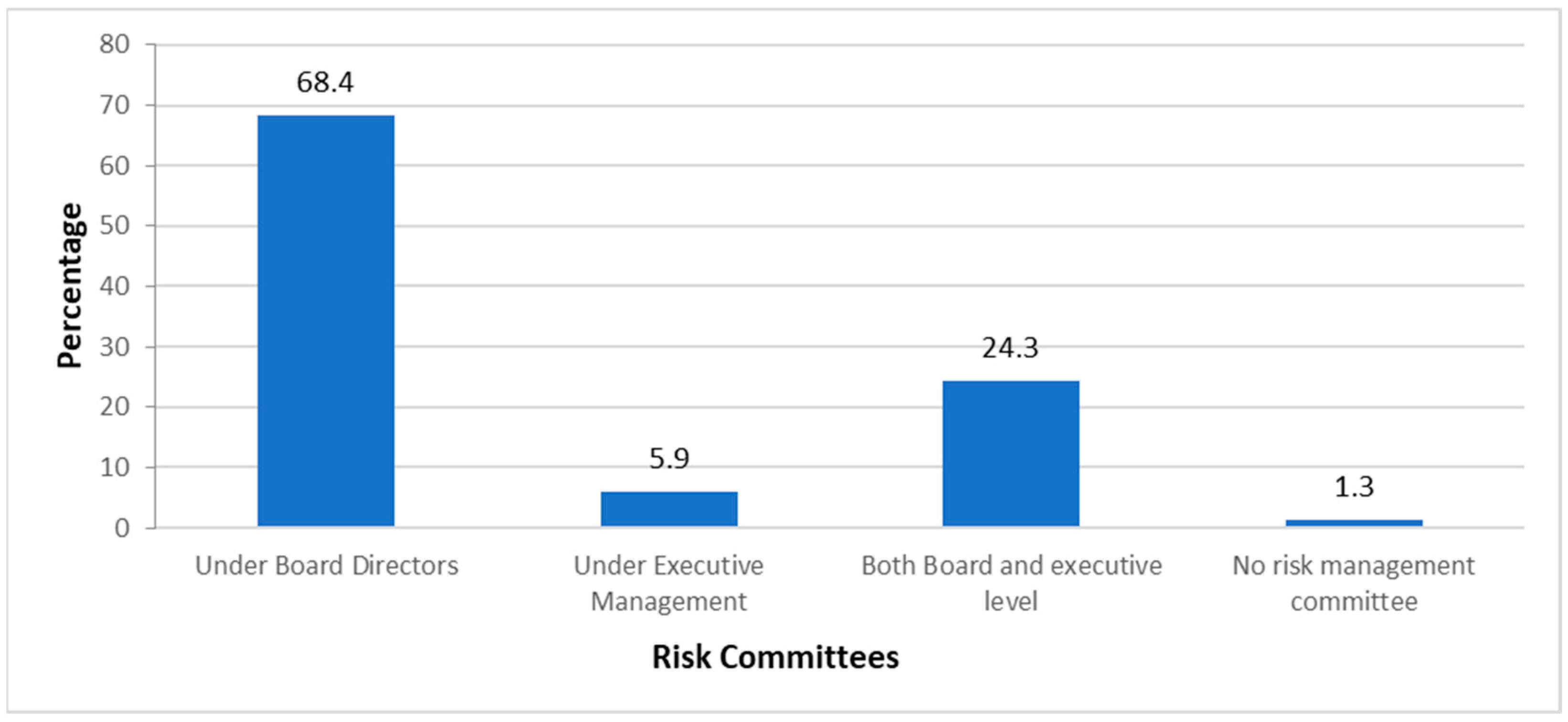

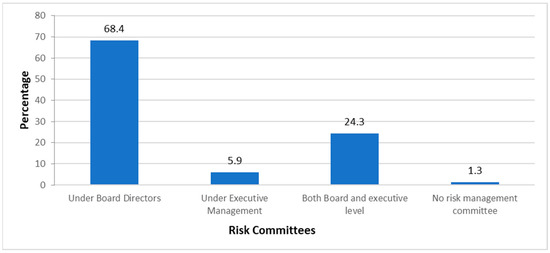

Risk Management Committee Structure

The adoption of a holistic risk management approach needs the institution of a board risk committee (Bohnert et al. 2019, p. 237). Beasley et al. (2015, p. 221) also argued that a more mature ERM function might be developed by forming a management-level risk committee including the senior executives that can deliver direction to business unit managers to assess the impact of risk events.

The composition of the risk management committees is presented in Figure 2. The risk management committees of Ethiopian commercial banks were mainly under the board of directors (68.4%), followed by those at the board and executive management level (24.3% each). This indicated that the risk management committees were established under the board of directors in the majority of the target banks (92.7%). However, in some banks, the committee was functioning only under executive management, which is not appropriate because it can affect their independence (5.9%). The remaining 1.3% of the respondents responded that there was no risk management committee responsible for risk oversight activities.

Figure 2.

Risk management committees.

The result of the study established that the risk management function of Ethiopian commercial banks was mainly overseen by the risk management committee at the board level and encouraged the establishment of an independent risk management function. This was consistent with the findings of Ademe (2015, p. 36), who identified that all three Ethiopian commercial banks covered by the study have a committee at the board level. The study conducted by Gugsa (2018, p. 41) on Ethiopian insurance companies also revealed that 86.5% of the companies have established risk management committees at the board level, and 30.2% of the respondents agreed with the existence of risk management committees at the management level. On the contrary, the study conducted by Alemu (2020, p. 41) argued that risk management committees exist only in 9.8% of Ethiopian commercial banks.

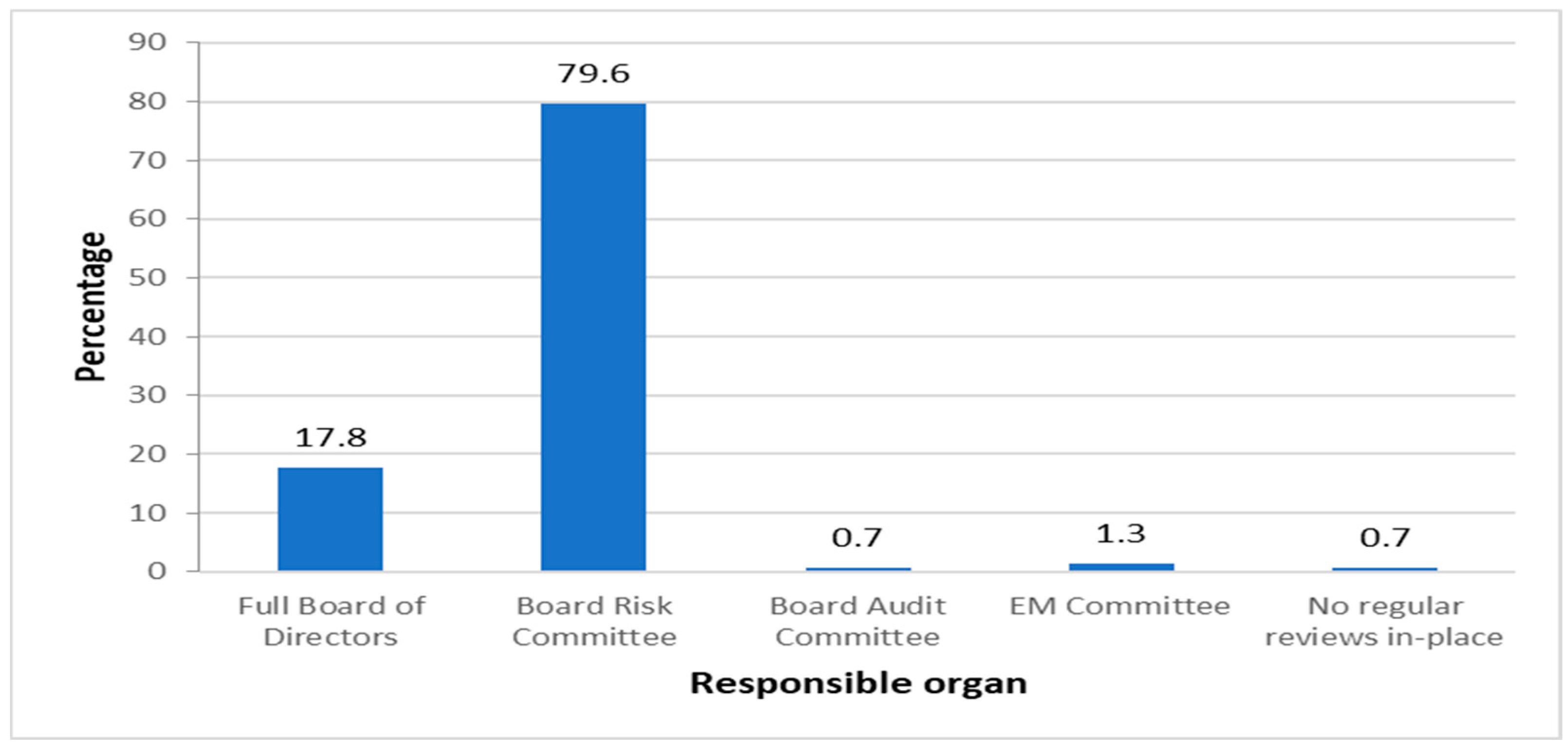

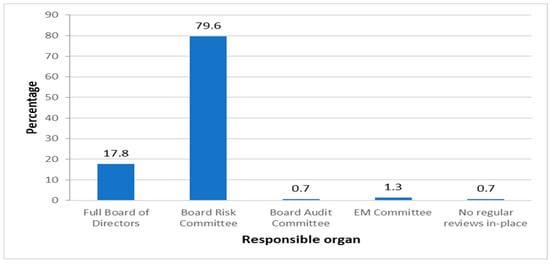

ERM Responsibility at Board Level

Firms necessitate establishing an independent risk management function that fully focuses on the risk management activities preferably reporting directly to the board or its risk management committee for independence. Figure 3 depicts the body responsible for reviewing ERM reports and outputs. The board risk committee was mainly responsible for reviewing ERM reports and outputs as reported by the majority (79.6%) of the respondents. The full board of directors was the second most frequently mentioned body, which is responsible for the task by 17.8% of the respondents.

Figure 3.

ERM review responsibility.

In addition, 1.3% and 0.7% of respondents responded that the ERM reports were reviewed by executive management and the board audit committee, respectively. The remaining 0.7% of respondents responded that there is no regular review of ERM reports at the bank level. This indicated that almost all of the ERM reports of the banks (98.14%) were reviewed by the full board or board-level risk or audit committees. This result is consistent with the study conducted by Ademe (2015, p. 42) that identified the risk management units of all three commercial banks covered by the research that were accountable to the board and enjoying independence. This result indicated that the board of directors of Ethiopian commercial banks undertake their risk oversight role by reviewing periodic ERM reports and it is practical in nearly all of the Ethiopian commercial banks.

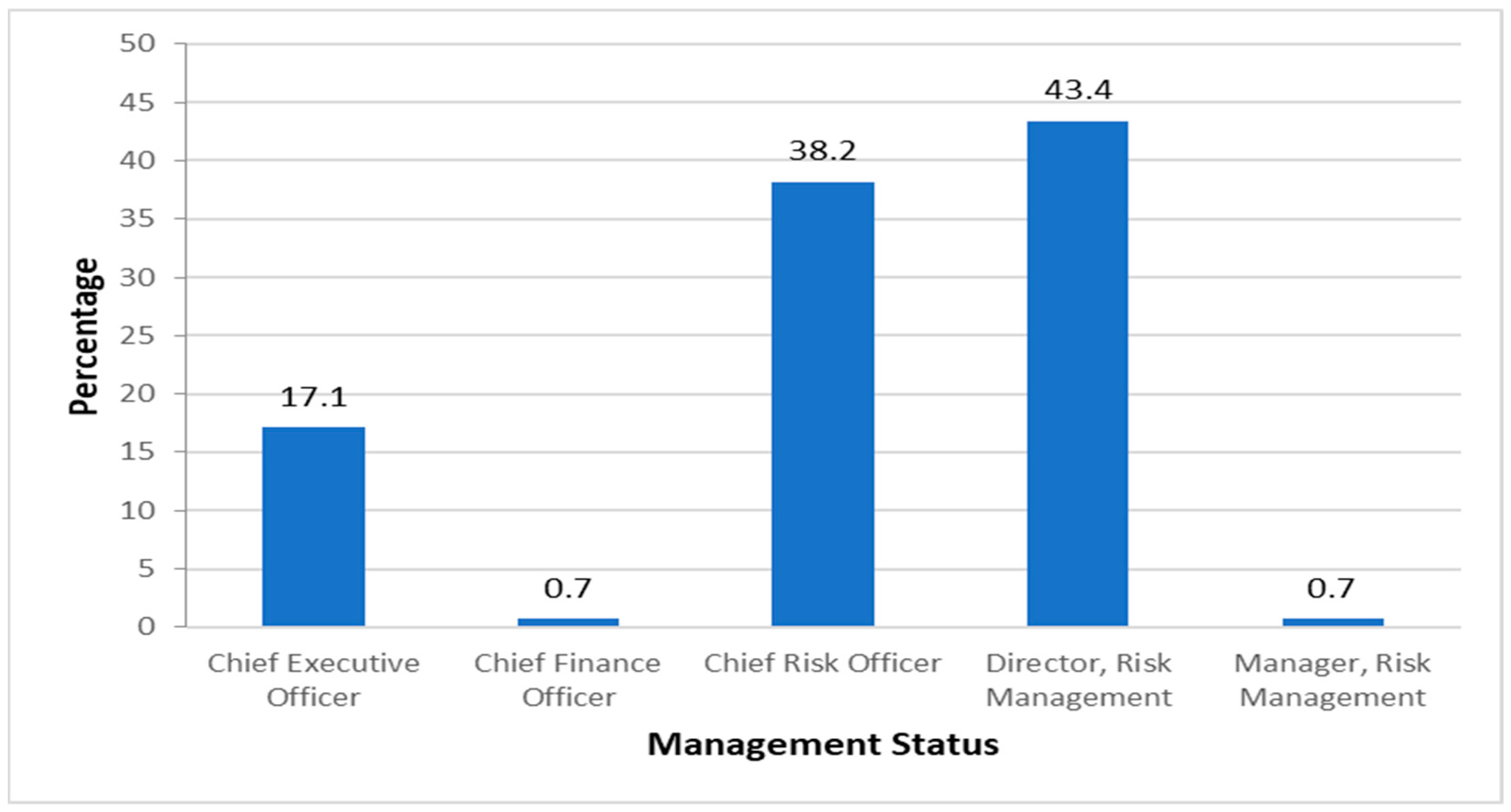

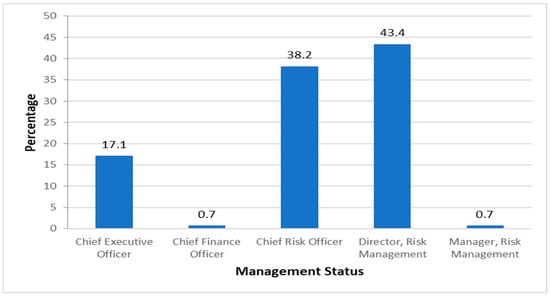

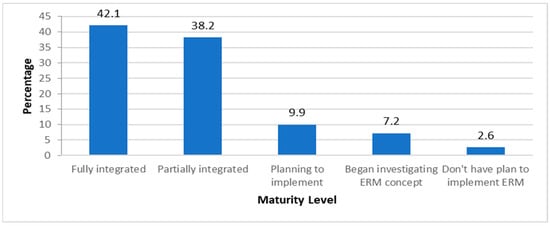

ERM Responsibility at Executive Level

Nowadays, the function of risk management is frequently led by a senior executive with the title of chief risk officer (Quon et al. 2012, p. 263). The presence of a CRO is one of the main determinant factors for ERM implementation, and the appointment of a CRO is recognised as an indicator of the existence of ERM implementation by a company (González et al. 2020, p. 117; Setiawan et al. 2021, p. 293). As shown in Figure 4, the result of the study revealed that the risk management director is assigned to ERM responsibility in most Ethiopian commercial banks (43.4%), followed by a chief risk officer (38.2%). In addition, 17.1% of the respondents responded that the chief executive officer is assigned to ERM responsibility at the executive level.

Figure 4.

ERM responsibility at executive level.

This indicates that only 38.2% of Ethiopian commercial banks assigned a CRO to lead their risk management function, and it is an indicator of the existence of ERM implementation in these banks. This data is consistent with the fact that of the 16 commercial banks, the survey distributed, only 6 (37.5%) assigned CROs to undertake the responsibility of their risk management function. Even though assigning a CRO is the main proxy of ERM implementation, most Ethiopian commercial banks have failed to assign CROs to their risk management function. Therefore, banks without a CRO should appoint one to ensure effective risk management and align with best practices in ERM. The NBE should enforce this appointment to strengthen the banking sector’s stability and ensure consistent ERM implementation across all banks.

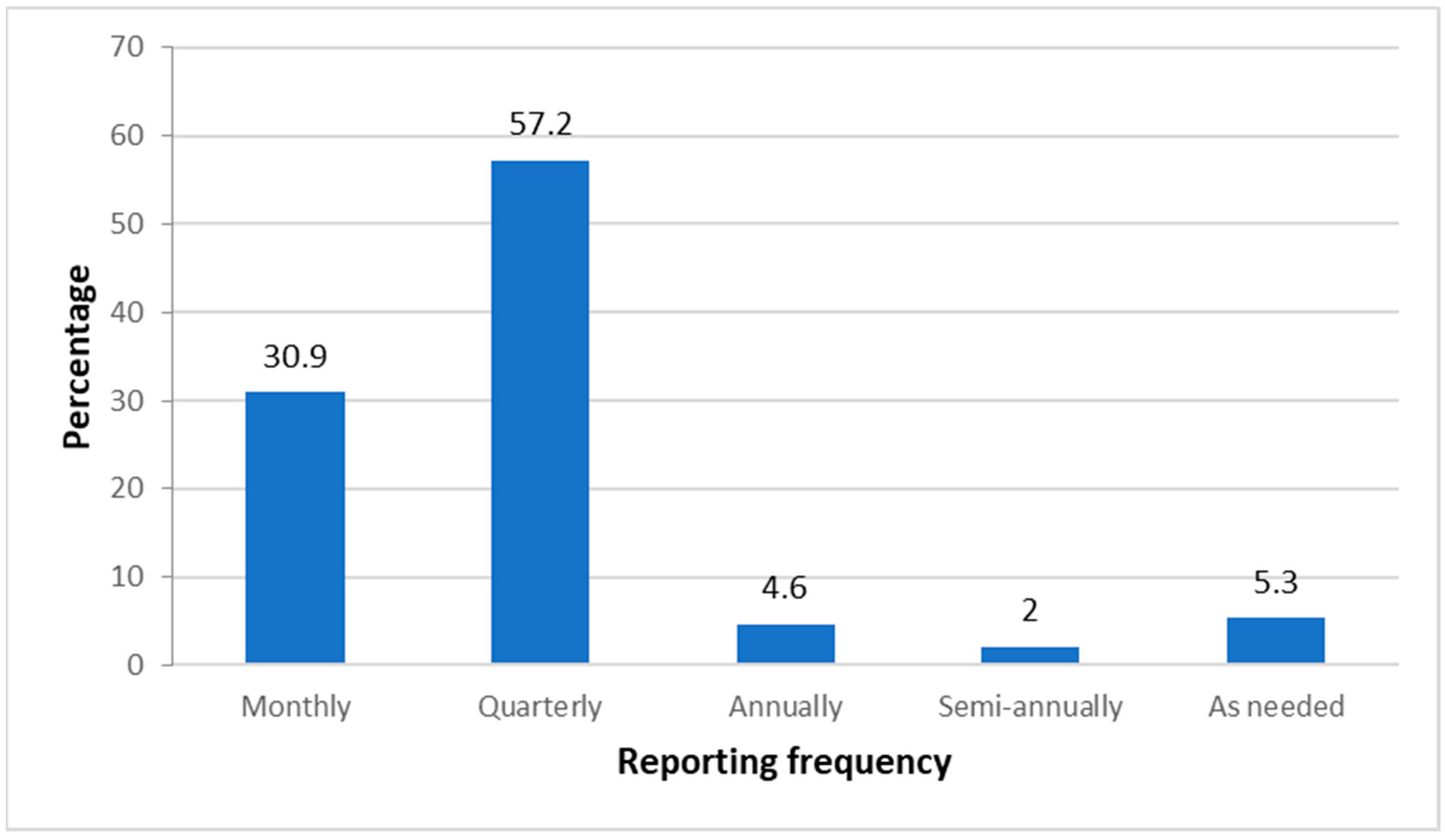

Frequency of Top Risk Executive Report to the Board

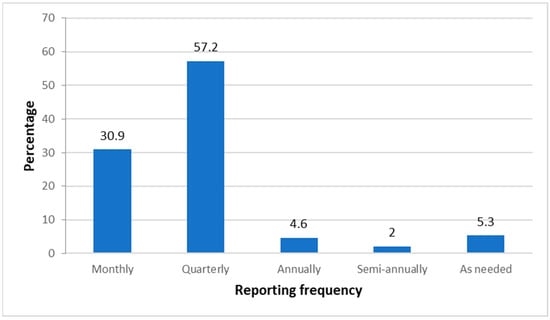

Regarding the frequency of top-risk executives’ reports to the board or board committee charged with enterprise risk oversight, 57.2% said that the report is quarterly and 30.9% said monthly. As needed, annually and semi-annually were replayed by 5.3%, 4.6%, and 2% of the respondents, respectively, as depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

ERM report frequency.

The NBE, under its corporate governance directive number SBB/71/2019, requested that the board risk committee of every Ethiopian bank hold regular meetings, at least once every month, and to report regularly to the full board (NBE 2019, p. 15). However, most of the banks (68.4%) have not delivered the top-risk executive reports to the board of directors on a monthly basis. Ademe (2015, p. 39) also revealed that Ethiopian commercial banks submitted quarterly reports to the board to ensure that all risks were identified and properly controlled and that the risk management programme was working effectively. These results indicate that the boards of these banks are not receiving timely monthly reports to effectively oversee and address risks proactively. Moreover, the findings suggest that most banks are not fully complying with the NBE’s requirement for monthly meetings, as only 30.9% of the banks delivered top-risk reports to the board on a monthly basis. This highlights a gap in risk oversight that could potentially hinder the banks’ ability to manage risks in a timely and responsive manner.

Risk Appetite and Risk Tolerance Statements

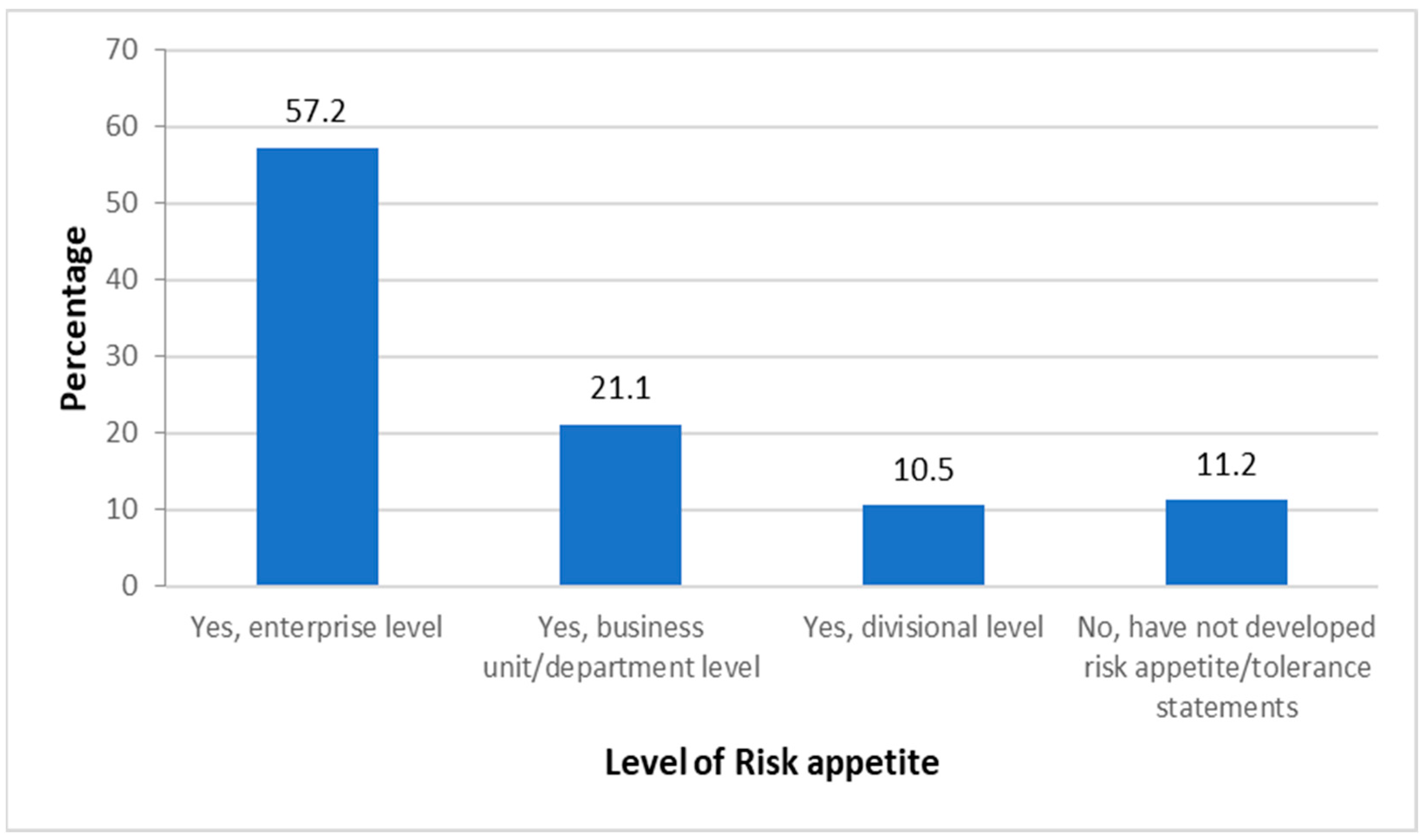

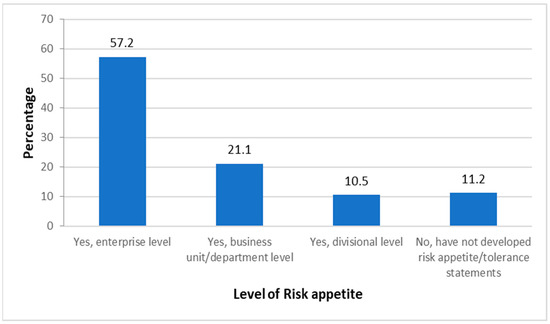

ERM frameworks involve a risk management policy, risk process, risk tolerance, risk appetite, risk governance, strong risk culture, and integrated decision making (Tuten 2018, p. 6). The enterprise-wide risk management process of financial institutions includes setting goals and risk appetite, risk identification, risk measurement and monitoring, and review (McShane 2018, p. 141). As shown in Figure 6, the result of the study showed that most Ethiopian commercial banks had developed risk appetite or tolerance statements at the enterprise level (57.2%). In addition, 21.1% and 10.5% of the respondents responded that their banks had developed a risk appetite at the business unit level and division level, respectively. The remaining 11.2% of respondents responded that their banks did not develop a risk appetite.

Figure 6.

Risk appetite or tolerance statements of Ethiopian banks.