The Low-Carbon Scheduling Optimization of Integrated Multispeed Flexible Manufacturing and Multi-AGV Transportation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- A mixed-integer programming (MIP) model is formulated to describe the LCSP-MSFM & MAGVT. The objectives of the MIP model are to optimize the comprehensive energy consumption and makespan simultaneously during the manufacturing operation.

- (2)

- In the proposed MIP model, a time-node model is built to describe the completion time per workpiece, and a comprehensive energy consumption model based on the operation process of the machine and AGV is established.

- (3)

- An estimation of distribution algorithm with a low-carbon scheduling heuristic strategy (EDA-LSHS) is developed to solve the proposed MIP model. In EDA, a novel probabilistic model is established to generate scheduling solutions satisfying the constraints. In LSHS, energy consumption optimization strategies for the machine processing, the AGV load state, and the AGV no-load transportation are proposed to guide the search direction of EDA.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Scheduling Optimization of Low-Carbon Manufacturing

2.2. Manufacturing Scheduling Considering Transportation

2.3. Overview

3. Formulation

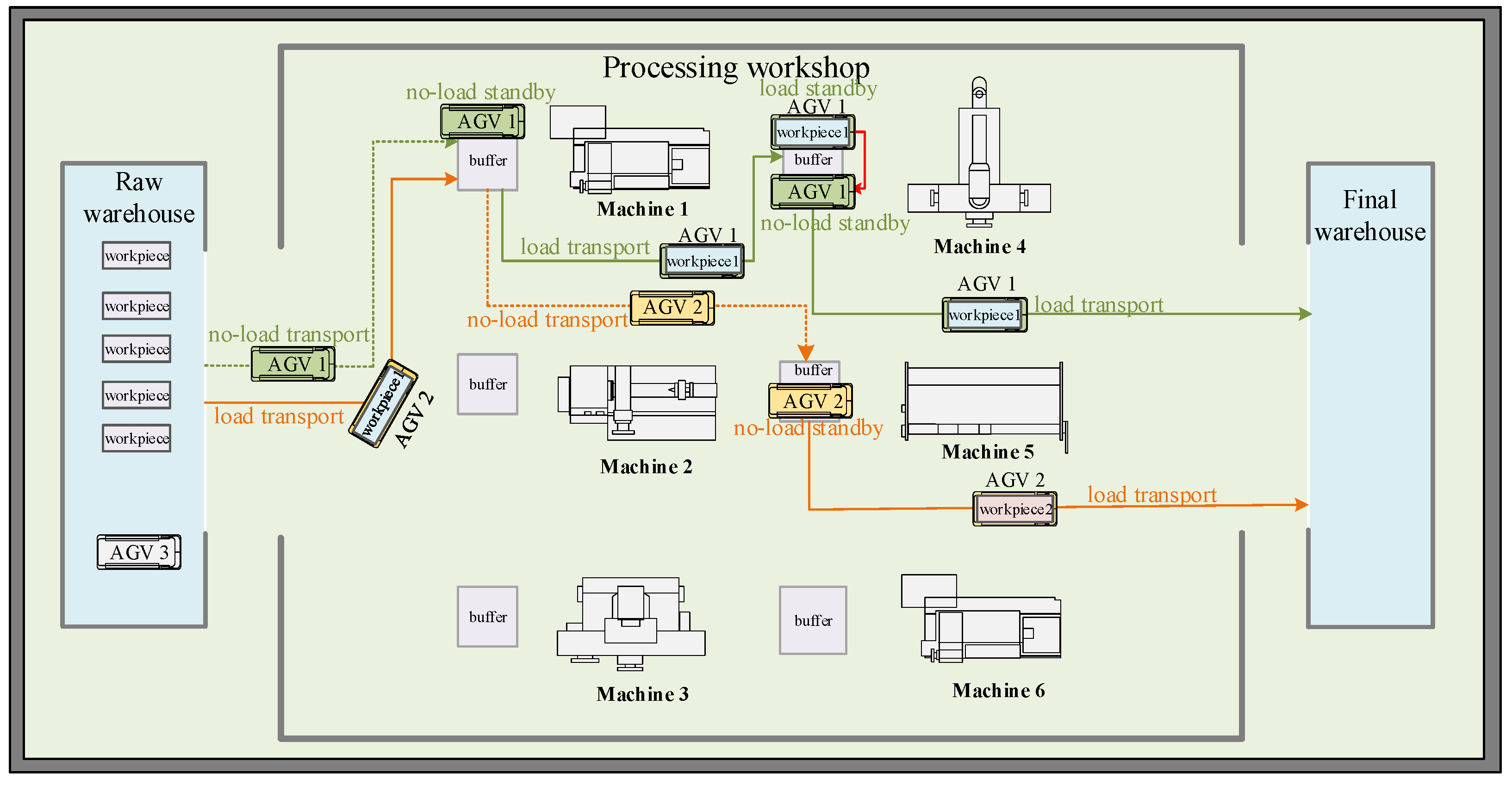

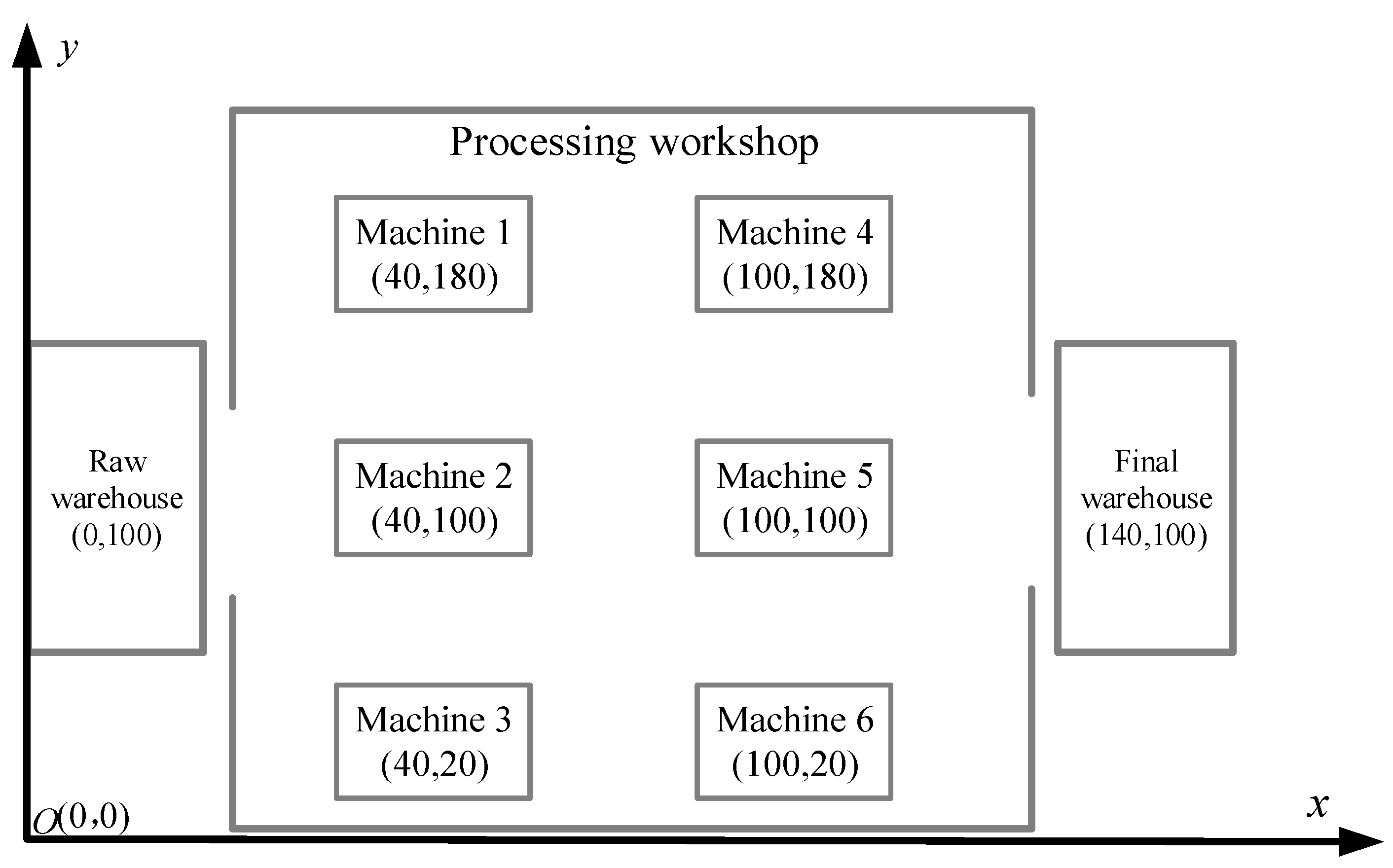

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. Assumptions

- Each machine can only process one workpiece at a time, and each workpiece can only be processed by one machine at the same time.

- Each AGV can only transport one workpiece at a time, and each workpiece can only be transported by one AGV at the same time.

- If and are processed on the same machine, does not need to be transported by the AGV.

- The machines that can be selected for each workpiece process are the machines available for it.

- All AGVs are fully charged and fault-free during the makespan.

- Assume that the raw warehouse is virtual machine and the final warehouse is virtual machine ; each workpiece has additional transportation to deliver the finished workpiece to the final warehouse.

- The starting point of all AGVs and workpieces is in the raw material warehouse, and the ending point is in the finished product warehouse.

- The machine only turns on when the first workpiece on it arrives and turns off only when the last workpiece on it completes.

3.3. Time-Node Model

3.3.1. The Start Time of No-Load State of AGV

3.3.2. The End Time of No-Load State of AGV

3.3.3. The Start Time of Load State of AGV

3.3.4. The End Time of Load State of AGV

3.3.5. The Start Time of Processing State of Machine

3.3.6. The End Time of Processing State of Machine

3.4. Comprehensive Energy Consumption Model

3.4.1. The Energy Consumption of the Machine Operation Process

- (1)

- The energy consumption of the standby state of the machine

- (2)

- The energy consumption of the processing state of the machine

- (3)

- The total energy consumption of the machine operation

3.4.2. The Energy Consumption of the AGV Operation

- (1)

- The energy consumption of the no-load transportation of the AGV

- (2)

- The energy consumption of the load transportation of the AGV

- (3)

- The energy consumption of the no-load standby state of the AGV

- (4)

- The energy consumption of the load standby state of the AGV

- (5)

- The total energy consumption of the AGV operation process

3.4.3. The Comprehensive Energy Consumption in the Workshop

3.5. The Formulation of the Mixed-Integer Programming Model

4. Methodology

4.1. The EDA-LSHS

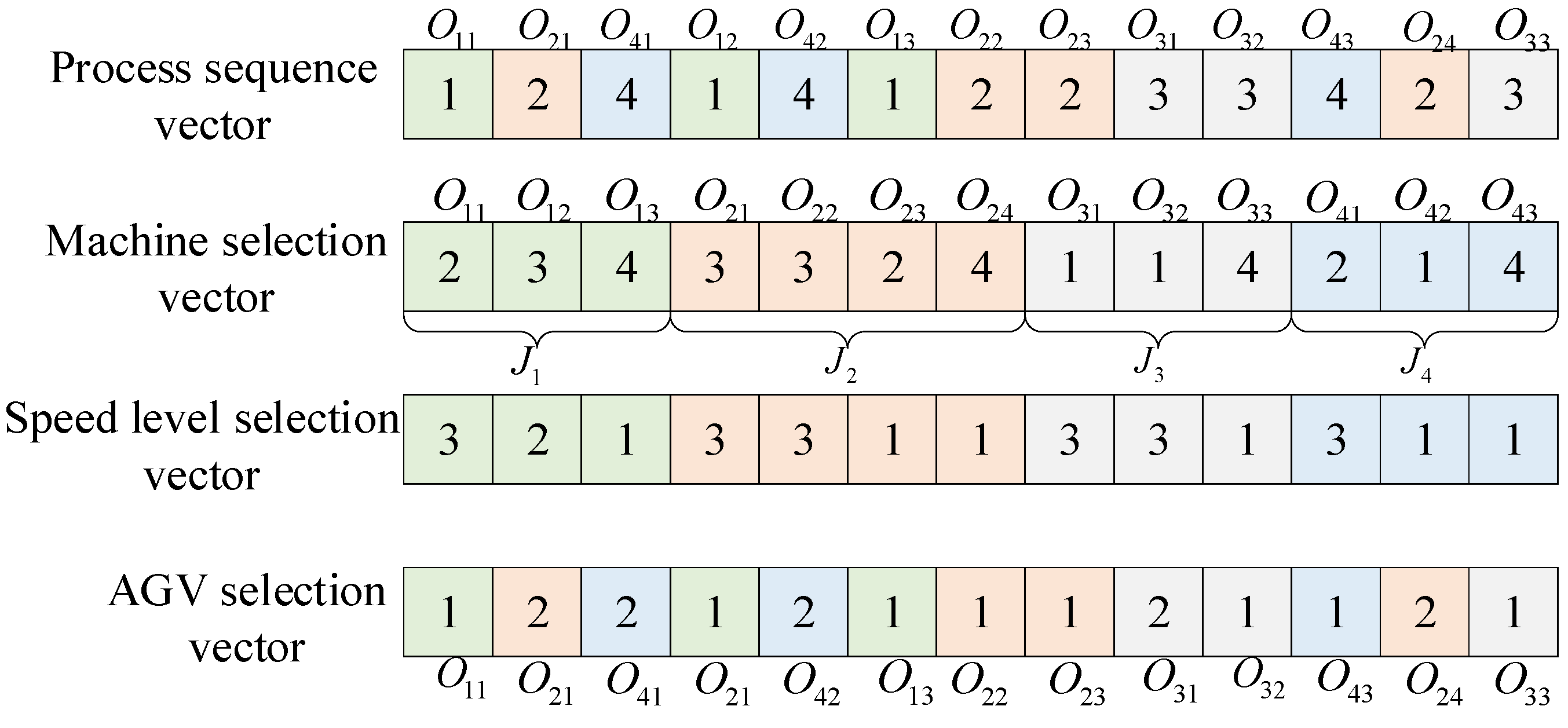

4.2. Representation of the Solution

4.3. Encoding and Decoding

4.4. Low-Carbon Scheduling Heuristic Strategy

4.4.1. Strategy 1: Machine Processing Energy Consumption Optimization

4.4.2. Strategy 2: AGV Load State Energy Consumption Optimization

4.4.3. Strategy 3: AGV No-Load Transportation Energy Consumption Optimization

4.5. Estimation of Distribution Algorithm

4.5.1. Population Initialization and Fitness Value

4.5.2. Probability Model and Update Mechanism

4.5.3. Generate New Population

5. Case Study

5.1. Data Source

5.2. Performance Analysis

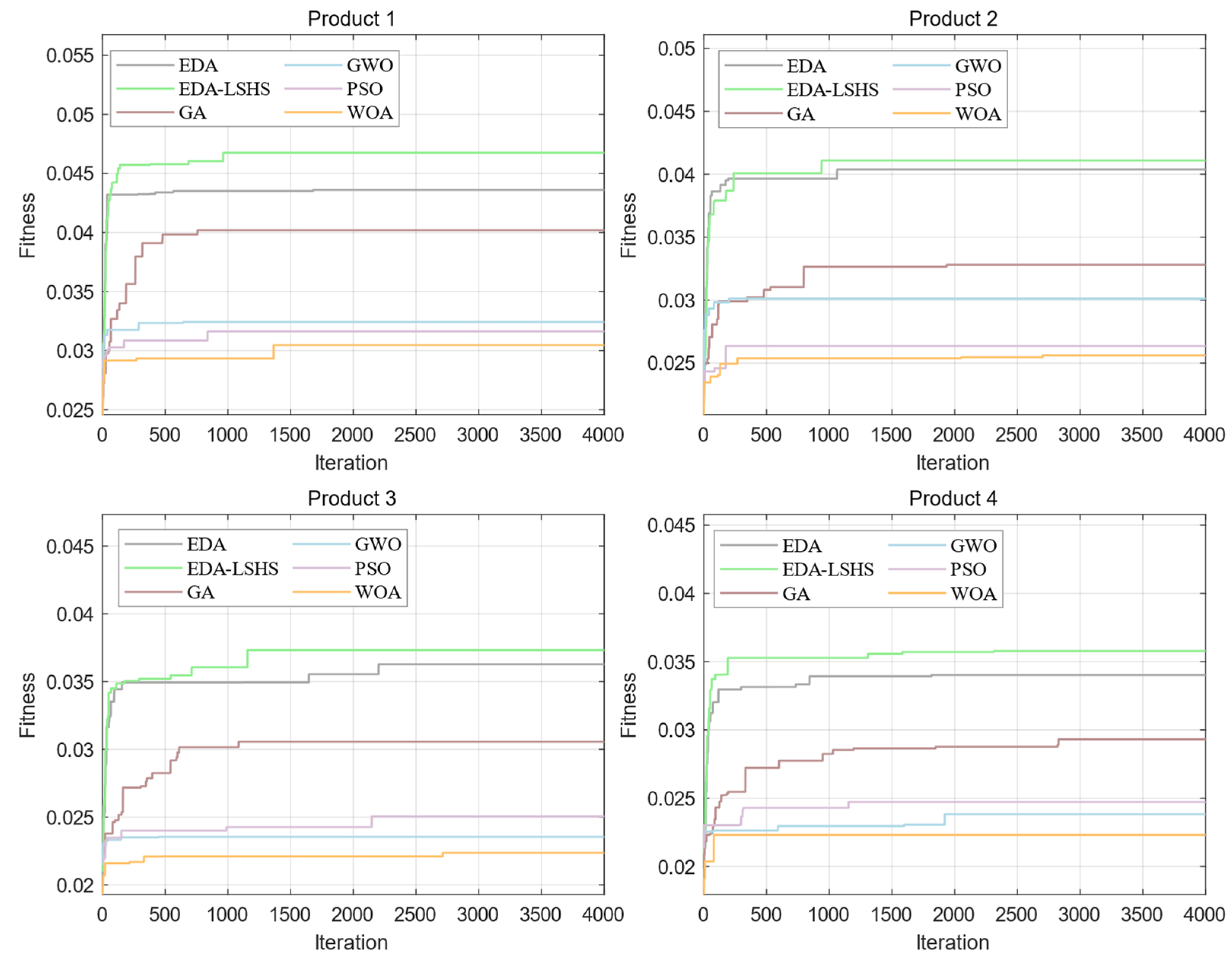

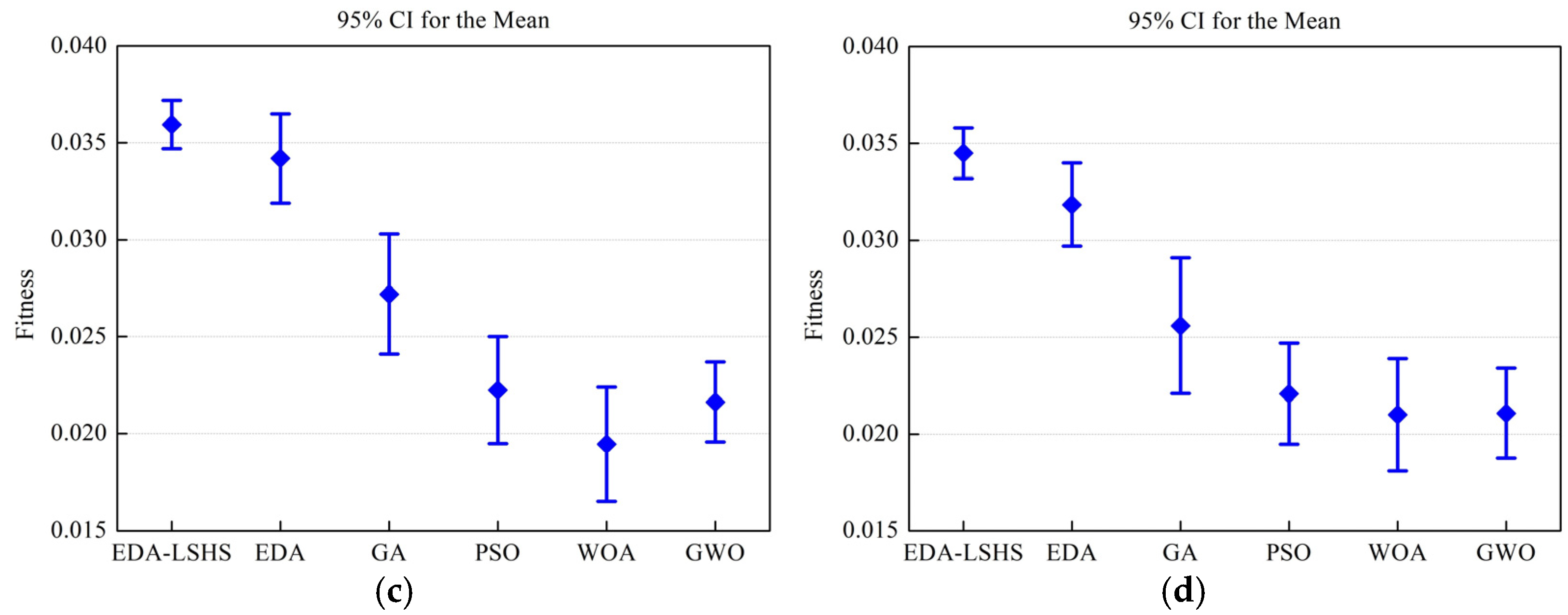

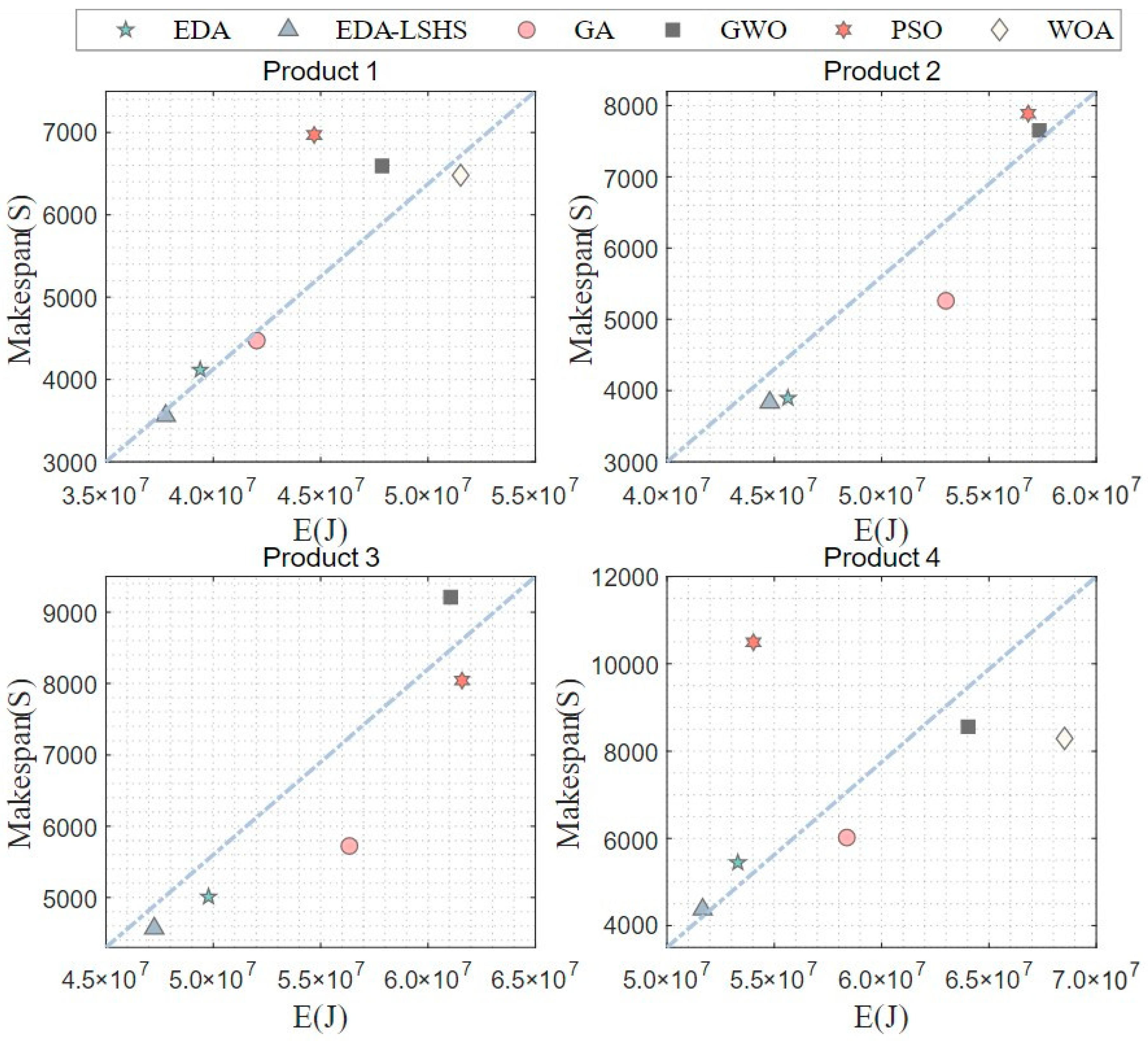

5.2.1. Comparative Experiment Analysis

- (1)

- EDA-LSHS: the estimation of distribution algorithm with low-carbon scheduling heuristic strategy.

- (2)

- EDA: the estimation of distribution algorithm.

- (3)

- GA: the genetic algorithm.

- (4)

- PSO: the particle swarm optimization algorithm.

- (5)

- WOA: the whale optimization algorithm.

- (6)

- GWO: the grey wolf optimization algorithm.

- (1)

- The EDA has better search ability than the GA, PSO, GWO, and WOA in the LCSP-MSFM & MAGVT, which provides a basic guarantee for the embedding of heuristic strategies.

- (2)

- The addition of the LSHS further improves the performance and stability of the EDA in the LCSP-MSFM & MAGVT.

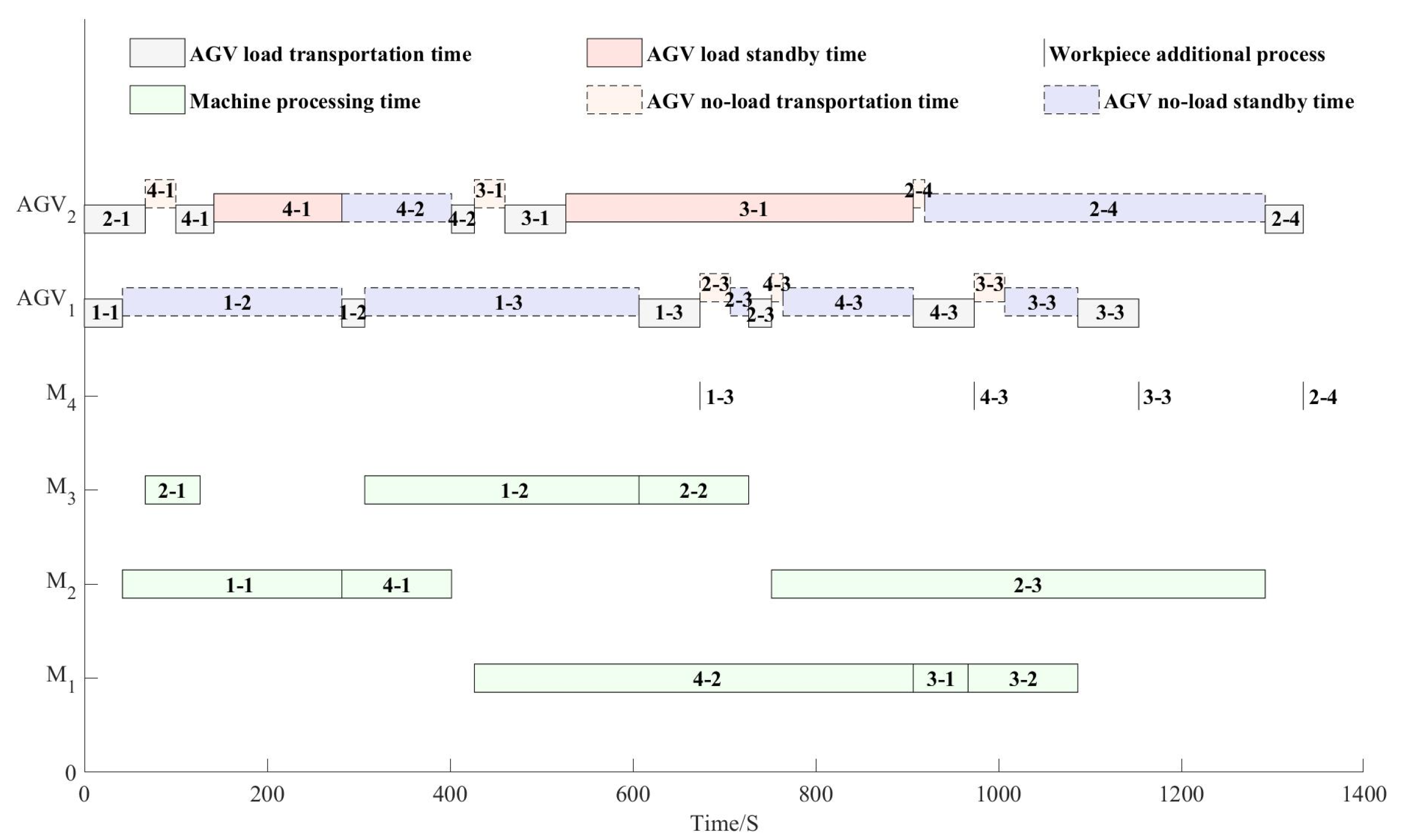

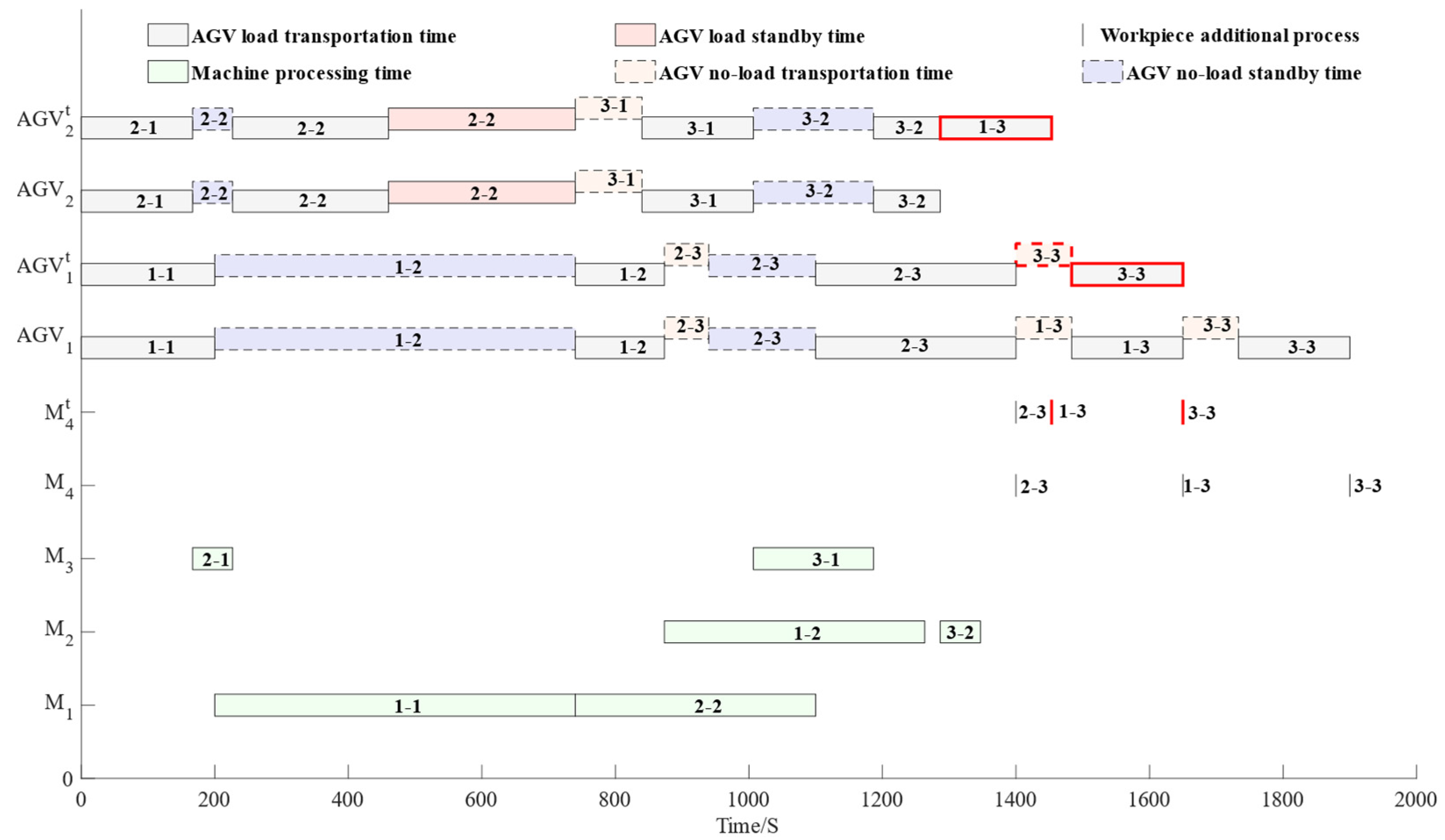

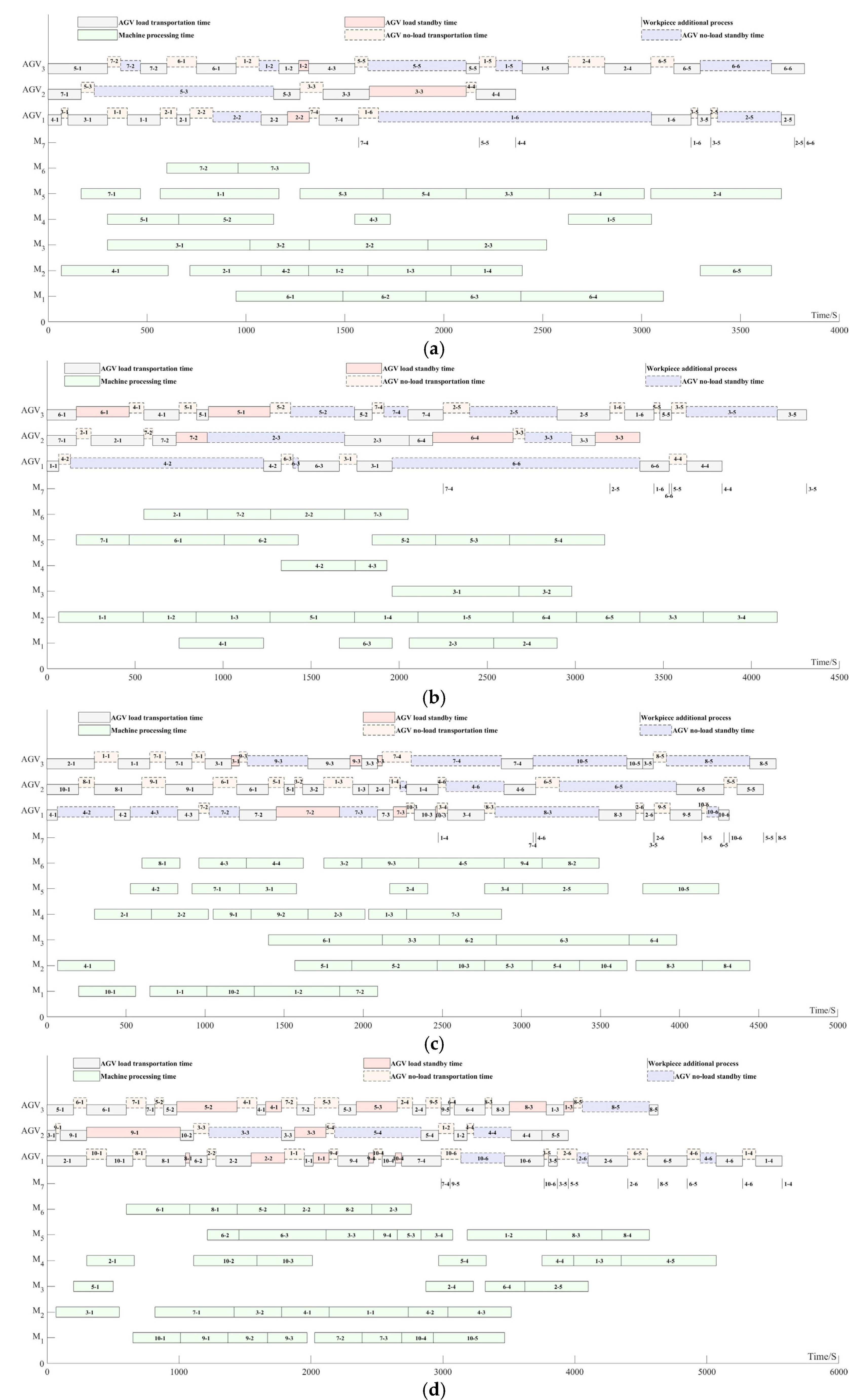

5.2.2. Optimization Strategy Analysis

- (1)

- According to the solution analysis, the three sub-strategies of the LSHS have obvious optimization effects, which not only improves the energy efficiency of machines and AGVs but also shortens the makespan.

- (2)

- As the complexity of product instances increases, the EDA-LSHS still maintains good optimization performance.

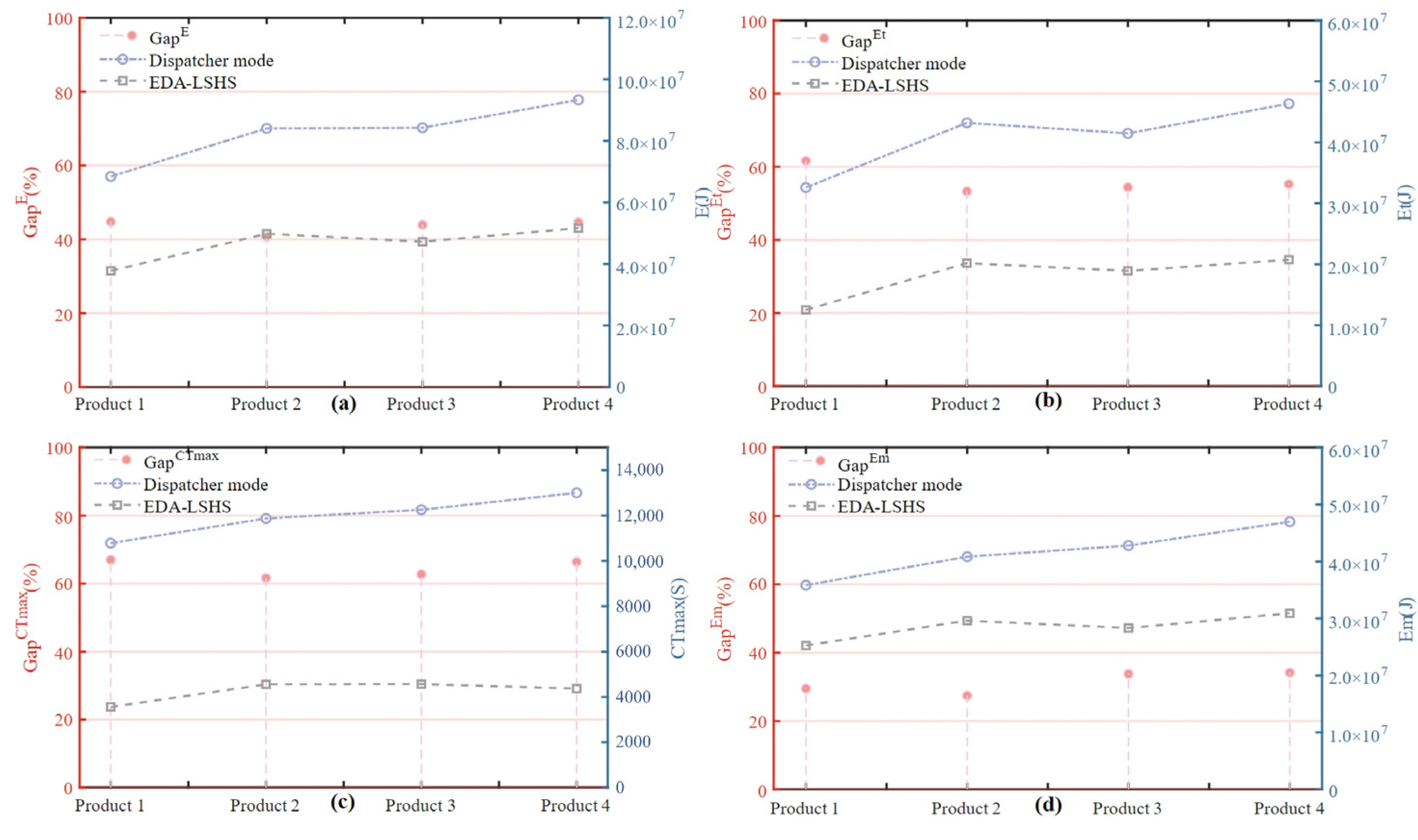

5.3. Low-Carbon Scheduling Analysis

5.3.1. Comprehensive Optimization Analysis

- (1)

- The EDA-LSHS and EDA have better comprehensive optimization effects and balanced optimization abilities than the other algorithms.

- (2)

- As the complexity of the products increases, the EDA-LSHS can still maintain favorable low-carbon scheduling optimization ability.

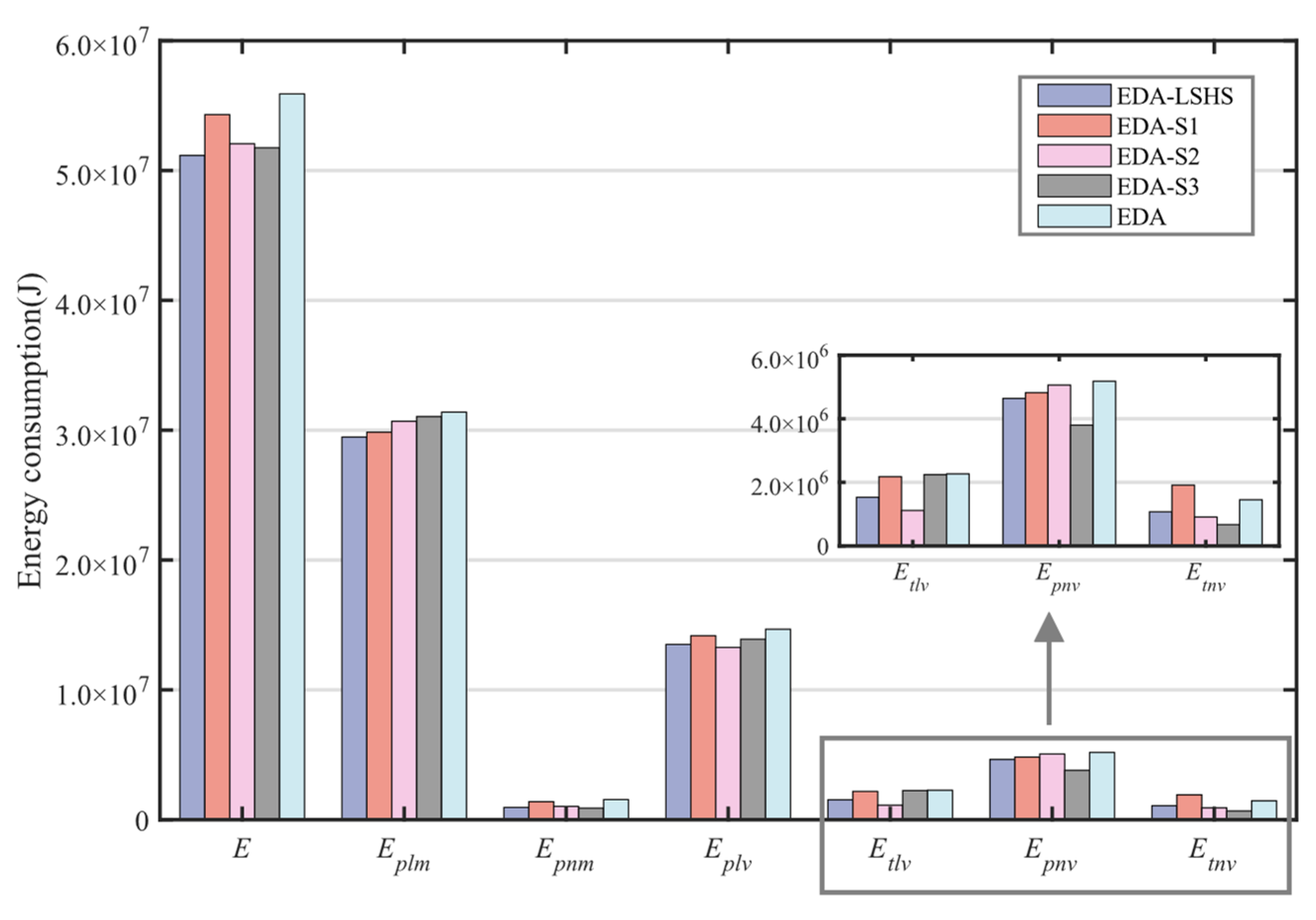

5.3.2. Energy Consumption Analysis

- (1)

- EDA-LSHS: the estimation of distribution algorithm with the low-carbon scheduling heuristic strategy.

- (2)

- EDA-S1: the estimation of distribution algorithm with strategy 1, machine processing energy consumption optimization with low-carbon scheduling heuristic strategy.

- (3)

- EDA-S2: the estimation of distribution algorithm with strategy 2, AGV load state energy consumption optimization with low-carbon scheduling heuristic strategy.

- (4)

- EDA-S3: the estimation of distribution algorithm with strategy 3, AGV no-load transportation consumption optimization with low-carbon scheduling heuristic strategy.

- (5)

- EDA: the estimation of distribution algorithm.

- (1)

- The single strategy 1, strategy 2, and strategy 3 in the LSHS have noticeable optimization effects on the energy consumption of machine processing, AGV load state, and AGV no-load transportation process, respectively.

- (2)

- The EDA-LSHS integrates the advantages of three sub-strategies. It has better optimization effects than the EDA for different types of energy consumption.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- To extend this study to the current major workshop types in manufacturing enterprises.

- (2)

- To study the impact of co-scheduling between humans and machines.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| The number of machines. | |

| The number of workpieces. | |

| The number of AGVs. | |

| Represents workpiece , . | |

| Represents machine , . | |

| Represents AGV , . | |

| The set of processes for workpiece ,. | |

| The total processes of all workpieces, . | |

| The set of available speed levels for machine , . | |

| The process of workpiece , . | |

| The standby power of the speed-level on machine . | |

| The machining power of the speed-level on the machine . | |

| The no-load transportation power of AGV. | |

| The load transportation power of AGV. | |

| The no-load standby power of AGV. | |

| The load standby power of AGV. | |

| The no-load transportation speed of AGV. | |

| The load transportation speed of AGV. | |

| Represents the transportation task of process . | |

| Represents a positive infinite number. | |

| Two-dimensional plane distance from machine to machine . | |

| The set of machines available for process , . | |

| The machining time of the speed-level of on the machine , . | |

| The machining starts time of the process on the speed-level on the machine . | |

| The machining end time of the process on the speed-level on the machine . | |

| The start time of the no-load state of the transportation task on . | |

| The end time of the no-load state of the transportation task on . | |

| The start time of the load state of the transportation task on . | |

| The end time of the load state of the transportation task on . | |

| The time of completing in AGV no-load transportation. | |

| The time of completing in AGV load transportation. | |

| The time of completing in AGV no-load standby. | |

| The time of completing in AGV load standby. | |

| The energy consumption of completing in the machine processing state. | |

| The energy consumption of completing in the machine standby state. | |

| The total energy consumption of the machine operation process in the makespan. | |

| The energy consumption of completing in AGV no-load transportation. | |

| The energy consumption of completing in AGV load transportation. | |

| The energy consumption of completing in AGV no-load standby. | |

| The energy consumption of completing in AGV load standby. | |

| The total energy consumption of the AGV operation process in the makespan. | |

| The total comprehensive energy consumption in the makespan. | |

| Represents the makespan. | |

| The decision variable of the machine processing. | |

| The decision variable of the machine processing order. | |

| The decision variable of the AGV transportation. | |

| The decision variable of the AGV transportation sequence. | |

| The decision variable of the AGV location. |

References

- Gao, P.; Yue, S.; Chen, H. Carbon emission efficiency of China’s industry sectors: From the perspective of embodied carbon emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wen, M.; Cui, Y.; Ming, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, C.; Ampah, J.D.; Jin, C.; Huang, H.; Liu, H. Effects of Methanol Application on Carbon Emissions and Pollutant Emissions Using a Passenger Vehicle. Processes 2022, 10, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Kang, H.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, D. Modified multi-crossover operator nsga-iii for solving low carbon flexible job shop scheduling problem. Processes 2020, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Deng, Q.; Gong, G.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Q. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms with heuristic decoding for hybrid flow shop scheduling problem with worker constraint. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Ye, C. Green scheduling of distributed two-stage reentrant hybrid flow shop considering distributed energy resources and energy storage system. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Li, P. Energy-efficient distributed heterogeneous welding flow shop scheduling problem using a modified MOEA/D. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 62, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, D.; Shen, C.; Yang, B. An improved multi-objective whale optimization algorithm for the hybrid flow shop scheduling problem considering device dynamic reconfiguration processes. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 174, 114793. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Liao, W.; Zhang, L. Hybrid energy-efficient scheduling measures for flexible job-shop problem with variable machining speeds. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 197, 116785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Z. Multi-objective optimization scheduling for manufacturing process based on virtual workflow models. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 122, 108786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, R.G.; Ranjbar, M. Minimizing the total tardiness and the total carbon emissions in the permutation flow shop scheduling problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 138, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Huang, Y.; Meng, L.; Gao, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, J. A Pareto-based collaborative multi-objective optimization algorithm for energy-efficient scheduling of distributed permutation flow-shop with limited buffers. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2022, 74, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.X.; Han, Y.Y.; Zhang, B.; Meng, L.L.; Liu, Y.P.; Pan, Q.K.; Gong, D.W. An improved iterated greedy algorithm for the energy-efficient blocking hybrid flow shop scheduling problem. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2022, 69, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, R.; Voß, S. Fixed set search application for minimizing the makespan on unrelated parallel machines with sequence-dependent setup times. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 110, 107521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Peng, J.; Xiao, X.; Wu, S. An effective approach for the dual-resource flexible job shop scheduling problem considering loading and unloading. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 707–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Hu, Y.; Luo, W.; Wang, L.; Wu, R. A multi-objective scheduling method for distributed and flexible job shop based on hybrid genetic algorithm and tabu search considering operation outsourcing and carbon emission. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Wu, R.; Guo, K. An improved artificial bee colony algorithm for solving multi-objective low-carbon flexible job shop scheduling problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 95, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chang, F. An adaptive ensemble deep forest based dynamic scheduling strategy for low carbon flexible job shop under recessive disturbance. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Gong, W.; Lu, C. Self-adaptive multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling with fuzzy processing time. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 168, 108099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakovitis, N.; Li, D.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, X. Novel approach to energy-efficient flexible job-shop scheduling problems. Energy 2022, 238, 121773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Wang, J. Robust scheduling for flexible machining job shop subject to machine breakdowns and new job arrivals considering system reusability and task recurrence. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 203, 117489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, S.; Palacios, J.J.; Puente, J.; Vela, C.R.; González-Rodríguez, I. Multi-objective enhanced memetic algorithm for green job shop scheduling with uncertain times. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2022, 68, 101016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Tan, J. Intelligent factory many-objective distributed flexible job shop collaborative scheduling method. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 164, 107884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, T.; Wang, B. A discrete differential evolution algorithm for flow shop group scheduling problem with sequence-dependent setup and transportation times. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Wang, L. A cooperative memetic algorithm with feedback for the energy-aware distributed flow-shops with flexible assembly scheduling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 168, 108126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Xi, S.H.; Chen, Q.X.; Smith, J.M.; Mao, N.; Li, X. Performance analysis of a flexible flow shop with random and state-dependent batch transport. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 982–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C. Research on flexible job shop scheduling under finite transportation conditions for digital twin workshop. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 72, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Chiong, R.; Li, W.; Budhi, G.S.; Zhang, Y. A multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for achieving energy efficiency in production environments integrated with multiple automated guided vehicles. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 243, 108315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, G.; Lu, J.; Zhang, W. A hybrid many-objective evolutionary algorithm for flexible job-shop scheduling problem with transportation and setup times. Comput. Oper. Res. 2021, 132, 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, S.; Wang, L. Integrated green scheduling optimization of flexible job shop and crane transportation considering comprehensive energy consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 765–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chung, S.H.; Wen, X.; Ma, H.L. Novel robotic job-shop scheduling models with deadlock and robot movement considerations. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 149, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Yuan, X.; Huang, G.; Liu, Z. Low-carbon joint scheduling in flexible open-shop environment with constrained automatic guided vehicle by multi-objective particle swarm optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 111, 107695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Fu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Pu, X.; Luo, L. Digital-twin driven energy-efficient multi-crane scheduling and crane number selection in workshops. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Chow, M.Y. Computational intelligence-based energy management for a large-scale PHEV/PEV enabled municipal parking deck. Appl. Energy 2012, 96, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Arias, M.J.; dos Santos, A.M.; Altamiranda, E. Evolutionary Algorithm to Support Field Architecture Scenario Screening Automation and Optimization Using Decentralized Subsea Processing Modules. Processes 2021, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Tian, G.; Liu, R.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z. Power Parametric Optimization of an Electro-Hydraulic Integrated Drive System for Power-Carrying Vehicles Based on the Taguchi Method. Processes 2022, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AGV State | Load Transport | Load Standby | No-Load Transport | No-Load Standby |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power (W) | 2500 | 800 | 1800 | 300 |

| Speed (m/s) | 0.6 | - | 1.2 | - |

| Power (W) | Speed Level 1 | Speed Level 2 | Speed Level 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Standby | Process | Standby | Process | Standby | |

| Machine 1 | 1120 | 170 | 1460 | 240 | 1780 | 310 |

| Machine 2 | 1340 | 230 | 1750 | 300 | 2150 | 370 |

| Machine 3 | 1050 | 160 | 1370 | 220 | 1680 | 280 |

| Machine 4 | 1210 | 190 | 1580 | 260 | 1940 | 330 |

| Machine 5 | 1170 | 180 | 1530 | 260 | 1880 | 320 |

| Machine 6 | 1290 | 210 | 1680 | 290 | 2070 | 360 |

| Product | EDA-LSHS | Dispatcher Mode | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | Et | Em | CTmax | E | Et | Em | CTmax | |

| 1 | 3.77 | 1.25 | 2.53 | 3.56 | 6.84 | 3.27 | 3.58 | 10.78 |

| 2 | 4.98 | 2.01 | 2.96 | 4.55 | 8.40 | 4.32 | 4.08 | 11.87 |

| 3 | 4.72 | 1.89 | 2.83 | 4.57 | 8.43 | 4.14 | 4.27 | 12.25 |

| 4 | 5.16 | 2.07 | 3.09 | 4.37 | 9.33 | 4.63 | 4.70 | 13.01 |

| Max gap | 44.78 | 61.60 | 34.19 | 66.98 |

| Average gap | 43.52 | 56.12 | 31.24 | 64.43 |

| Min gap | 40.73 | 53.27 | 27.45 | 61.62 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Luo, Q.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Li, Y. The Low-Carbon Scheduling Optimization of Integrated Multispeed Flexible Manufacturing and Multi-AGV Transportation. Processes 2022, 10, 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10101944

Liu Z, Luo Q, Wang L, Tang H, Li Y. The Low-Carbon Scheduling Optimization of Integrated Multispeed Flexible Manufacturing and Multi-AGV Transportation. Processes. 2022; 10(10):1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10101944

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhengchao, Qiang Luo, Lei Wang, Hongtao Tang, and Yibing Li. 2022. "The Low-Carbon Scheduling Optimization of Integrated Multispeed Flexible Manufacturing and Multi-AGV Transportation" Processes 10, no. 10: 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10101944

APA StyleLiu, Z., Luo, Q., Wang, L., Tang, H., & Li, Y. (2022). The Low-Carbon Scheduling Optimization of Integrated Multispeed Flexible Manufacturing and Multi-AGV Transportation. Processes, 10(10), 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10101944

_Tang.png)