Supply Chain Response during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multiple-Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

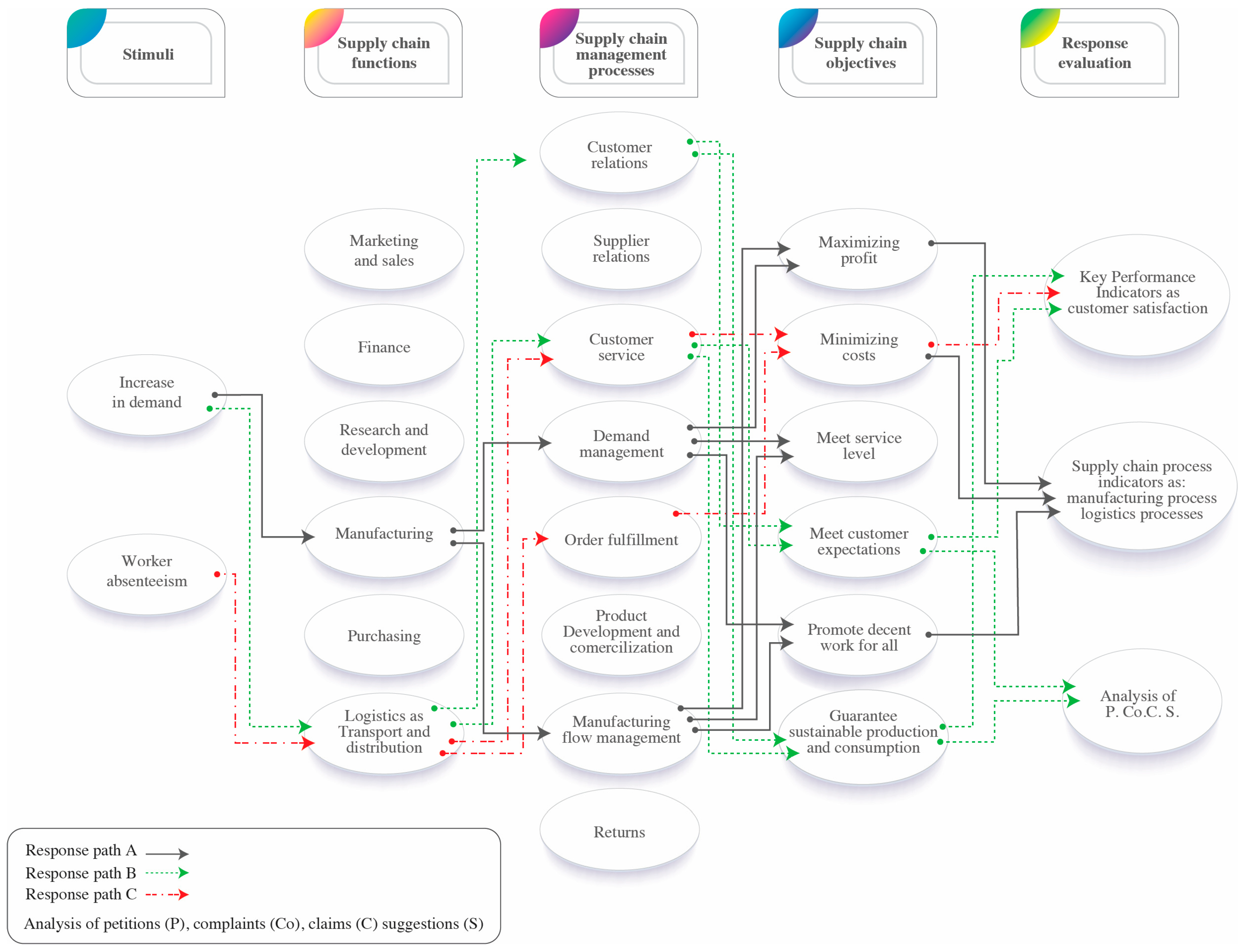

2.1. Supply Chain Response

2.2. Responses Implemented in the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.3. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on SCs around the World

2.4. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on SCs

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Defining the Research Questions

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Supply Chain Overview

3.3.1. Case Company A

3.3.2. Case Company B

3.3.3. Case Company C

3.3.4. Case Company D

3.3.5. Case Company E

3.4. Profile of the Interviewees

3.5. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Stimuli that Affected Company SC

4.2. Detection of the Stimuli that Affected Company SC

4.3. Planning of the Response to Stimuli Affecting Company SC

4.4. Evaluation of the Response to the Stimuli

4.5. Response Alternatives

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kritchanchai, D.; MacCarthy, B. Responsiveness of the order fulfilment process. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1999, 19, 812–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, O. Understanding the stimuli, scope, and impact of organizational transformation: The context of eBusiness technologies in supply chains. Strat. Change 2021, 30, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Mukherjee, A.A.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Srivastava, S.K. Supply chain management during and post-COVID-19 pandemic: Mitigation strategies and practical lessons learned. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 1125–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, A.R.; Kang, M.; Robb, C.A. Linking Supply Chain Disruption Orientation to Supply Chain Resilience and Market Performance with the Stimulus–Organism–Response Model. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrani, A.; Loukaides, E.G.; Elias, E.; Lunt, A.J. Exploration of alternative supply chains and distributed manufacturing in response to COVID-19: A case study of medical face shields. Mater. Des. 2020, 192, 108749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Chen, Y.-Y.; McDonald, M.; O’Neill, E. Dynamic Response Systems of Healthcare Mask Production to COVID-19: A Case Study of Korea. Systems 2020, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahiluoto, H.; Mäkinen, H.; Kaseva, J. Supplying resilience through assessing diversity of responses to disruption. Int. J. Oper. Prod. 2020, 40, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azyabi, N. How do information technology and knowledge management affect SMEs’ responsiveness to the coronavirus crisis? Bus. Inform. 2021, 15, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehme, T.; Aitken, J.; Turner, N.; Handfield, R. COVID-19 response of an additive manufacturing cluster in Australia. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 26, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.N.; Mishra, N.; Wulandhari, N.B.I.; Ramudhin, A.; Sivarajah, U.; Milligan, G. Supply chain agility responding to unprecedented changes: Empirical evidence from the UK food supply chain during COVID-19 crisis. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 26, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederico, G.F.; Kumar, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Impact of the strategic sourcing process on the supply chain response to the COVID-19 effects. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2021, 27, 1775–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margherita, A.; Heikkilä, M. Business continuity in the COVID-19 emergency: A framework of actions undertaken by world-leading companies. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollenkopf, D.A.; Ozanne, L.K.; Stolze, H.J. A transformative supply chain response to COVID-19. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Iqbal, U.; Gong, Y. The Performance of Resilient Supply Chain Sustainability in COVID-19 by Sourcing Technological Integration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giotopoulos, I.; Kontolaimou, A.; Tsakanikas, A. Digital responses of SMEs to the COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 1751–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoruyi, O.; Dakora, E.A.; Oluwagbemi, O.O. Insights into the impacts of and responses to COVID-19 pandemic: The South African food retail supply chains perspective. J. Transp. Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 16, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, U.; Aluko, O.; Ramanathan, R. Supply chain resilience and business responses to disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 2275–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; Cook, S.; Golden, A.; Iwane, M.A.; Kleiber, D.; Leong, K.M.; Mastitski, A.; Richmond, L.; Szymkowiak, M.; Wise, S. Review of adaptations of US Commercial Fisheries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic using the Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD) framework. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2022, 29, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mitchell, C.; Kushniruk, A.; Guitouni, A. Facing disruption: Learning from the healthcare supply chain responses in British Columbia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Manag. Forum 2022, 35, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, L.; Chatterjee, A.; Chatterjee, D. Critical Enablers that Mitigate Supply Chain Disruption: A Perspective from Indian MSMEs. Manag. Labour Stud. 2023, 48, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.M.; Armstrong, B.; Schaab-Rozbicki, S.; Young, G. Supply Chains & Working Conditions during the Long Pandemic. Daedalus 2023, 152, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, M.; Schmidt, C.G.; Wagner, S.M.; Swink, M. Firms’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, T.M.; Moscon, J.Z.; Junior, I.D.B.; Mendes, A.A.; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y. Public School Food Supply Chain during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of the City of Vitória (Brazil). Logistics 2022, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeo-Tad, N.; Jeenanunta, C.; Chumnumporn, K.; Nitisahakul, T.; Sanprasert, V. Resilient manufacturing: Case studies in Thai automotive industries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2021, 13, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanany, I.; Ali, M.H.; Tan, K.H.; Kumar, A.; Siswanto, N. A Supply Chain Resilience Capability Framework and Process for Mitigating the COVID-19 Pandemic Disruption. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, Z.; Khatir, M.V.; Rahimi, M. Robust design of a green-responsive closed-loop supply chain network for the ventilator device. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 53598–53618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, Z.; Ahmad, N.A.; Muhamad, M.R. Understanding responsiveness in manufacturing operations. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Research in Innovation and Sustainability, Melaka, Malaysia, 15–16 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hum, S.H.; Parlar, M.; Zhou, Y. Measurement and optimization of responsiveness in supply chain networks with queueing structures. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 264, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichhart, A.; Holweg, M. Creating the customer-responsive supply chain: A reconciliation of concepts. Int. J. Oper. Prod. 2007, 27, 1144–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, R.A.; Benedito, E. Supply Chain Response: Proposal for a General Definition. In Ensuring Sustainability: New Challenges for Organizational Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Stanske, S.; Lieberman, M.B. Strategic responses to crisis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyoko, A.T.; Erliza, A.; Alfonsus, M.; Suryo, L.; Sucipto, D.S. Strategic Adaptation to Response the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of Automotive Spare Parts Company in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Rome, Italy, 2–5 August 2021; pp. 922–932. Available online: http://www.ieomsociety.org/rome2020/proceedings/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Sharma, A.; Borah, S.B.; Moses, A.C. Responses to COVID-19: The role of governance, healthcare infrastructure, and learning from past pandemics. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hong, A.; Li, X.; Gao, J. Marketing innovations during a global crisis: A study of China firms’ response to COVID-19. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohenstein, N.O. Supply chain risk management in the COVID-19 pandemic: Strategies and empirical lessons for improving global logistics service providers’ performance. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2022, 33, 1336–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saïah, F.; Vega, D.; de Vries, H.; Kembro, J. Process modularity, supply chain responsiveness, and moderators: The Médecins Sans Frontières response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.R.; Akhter, F.; Sultana, M.M. SMEs in COVID-19 crisis and combating strategies: A systematic literature review (SLR) and A case from emerging economy. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2022, 9, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.K.; Lowe, A.; Herstein, J.J.; Trinidad, N.; Carvajal-Suarez, M.; Quintero, S.; Molina, D.; Schwedhelm, S.; Lowe, J.J. A rapid-response survey of essential workers in midwestern meatpacking plants: Perspectives on COVID-19 response in the workplace. J. Environ. Health 2021, 84, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Diao, Z.; Zanini, M.T. Business-to-business marketing responses to COVID-19 crisis: A business process perspective. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Venkatesh, M. Manufacturing and service supply chain resilience to the COVID-19 outbreak: Lessons learned from the automobile and airline industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Sethi, S.P.; Chung, S.H.; Choi, T.M. Reforming global supply chain management under pandemics: The GREAT-3Rs framework. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023, 32, 524–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowdon, A.W.; Saunders, M.J. Supply chain capacity to respond to COVID-19 in Newfoundland and Labrador: An integrated leadership strategy. In Healthcare Management Forum; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022; Volume 35, pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. The Global Economic Outlook during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Changed World. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlook-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- World Trade Organization [WTO]. Trade Falls Steeply in First Half of 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr858_e.htm (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Mańkowski, C.; Szmeter-Jarosz, A.; Jezierski, A. Managing Supply Chains during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Central Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 30, 90–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Alshazly, H.; Idris, S.A.; Bourouis, S. Evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on society, environment, economy, and education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppiah, K.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Ali, S.M. Modeling Impacts of COVID-19 in Supply Chain Activities: A Grey-DEMATEL Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldem, B.; Kluczek, A.; Bagiński, J. The COVID-19 Impact on Supply Chain Operations of Automotive Industry: A Case Study of Sustainability 4.0 Based on Sense–Adapt–Transform Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sombultawee, K.; Lenuwat, P.; Aleenajitpong, N.; Boon-Itt, S. COVID-19 and Supply Chain Management: A Review with Bibliometric. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunnusi, M.; Omotayo, T.; Hamma-Adama, M.; Awuzie, B.O.; Egbelakin, T. Lessons learned from the impact of COVID-19 on the global construction industry. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 20, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtner, P.; Darbanian, F.; Falatouri, T.; Udokwu, C. Impact of COVID-19 on the customer end of retail supply chains: A big data analysis of consumer satisfaction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.K. How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting global supply chains, logistics, and transportation? J. Int. Logist. Trade 2020, 18, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Navarrete, J.; Hauge, J.; López-Gómez, C. COVID-19’s impacts on global value chains, as seen in the apparel industry. Dev. Policy Rev. 2021, 39, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzón, G.; Felipe, L.; Mena, P.; Vivian, S.; Ruiz, J.; Humberto, C.; Restrepo, C.; Carlos, J. Aproximación a los Impactos de la Pandemia del COVID-19 en el Valle del Cauca. 2020. Available online: https://www.valledelcauca.gov.co/loader.php?lServicio=Tools2&lTipo=viewpdf&id=42221- (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Aday, S.; Aday, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual. Saf. 2020, 4, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Azevedo, A.L. COVID-19: Outcomes for global supply chains. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2020, 15, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Mangla, S.K.; Kazançoğlu, Y. COVID-19 impact on sustainable production and operations management. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2020, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautrims, A.; Schleper, M.C.; Cakir, M.S.; Gold, S. Survival at the expense of the weakest? Managing modern slavery risks in supply chains during COVID-19. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remko, V.H. Research opportunities for a more resilient post-COVID-19 supply chain–closing the gap between research findings and industry practice. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craighead, C.W.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Darby, J.L. Pandemics and supply chain management research: Toward a theoretical toolbox. Decis. Sci. 2020, 51, 838–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.U.; Hussain, A.; Masood, T.; Habib, M.S. Supply chain operations management in pandemics: A state-of-the-art review inspired by COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magableh, G.M. Supply chains and the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive framework. EMR 2021, 18, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Paul, S.K.; Kaisar, S.; Moktadir, M.A. COVID-19 pandemic related supply chain studies: A systematic review. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 148, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.S. Understanding the implications of pandemic outbreaks on supply chains: An exploratory study of the effects caused by the COVID-19 across four South Asian countries and steps taken by firms to address the disruptions. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2022, 52, 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.N. Responding to supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: A Black Swan event for omnichannel retailers. J. Transp. Supply Chain. Manag. 2021, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiers, J.; Seinhorst, J.; Zwanenburg, M.; Stek, K. Which strategies and corresponding competences are needed to improve supply chain resilience: A COVID-19 based review. Logistics 2022, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg, L.D.; Volpe, M. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation: A Road Map from Beginning to End; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Supply chain viability and the COVID-19 pandemic: A conceptual and formal generalisation of four major adaptation strategies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 3535–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiguashca, A.F.; García, A.C. Indice de Competitividad de Ciudades 2021, 1st ed.; Puntoaparte editores, Ed.; Panamericana Formas e Impresos S.A: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kähkönen, A.K. Conducting a case study in supply management. Oper. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 4, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.M.; Enz, M.G. Issues in supply chain management: Progress and potential. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 62, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajmi, A.; Adlan, N.; Lahyani, R. Assessment of Supply Chain Management Resilience within Saudi Medical Laboratories during COVID-19 Pandemic. Procedia CIRP 2021, 103, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomthanachai, S.; Wong, W.P.; Soh, K.L.; Lim, C.P. A global trade supply chain vulnerability in COVID-19 pandemic: An assessment metric of risk and resilience-based efficiency of CoDEA method. Res. Transp. Econ. 2022, 93, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Islam, S.M.; Khan, S.; Ahmad, H.; Ur Rahman, M.A.; Tomar, S.; Khan, M.Z. Assessment of challenges and problems in supply chain among retailers during COVID-19 epidemic through AHP-TOPSIS hybrid MCDM technique. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2022, 2, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the SC | SC Responses |

|---|---|

|

|

| Case | Economic Sector * | Industrial Activity | Number of Employees | Product Exportation Destination | Interview Duration (Minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Secondary | Pharmaceutical | 1200 | Andean Region | 70 |

| B | Secondary | Ready-to-assemble modular furniture manufacturer | 700 | South and Central America | 108 |

| C | Secondary | Aluminum profiles for various uses | 900 | The United States and the Caribbean | 63 |

| D | Tertiary | Marketer of products and services | 5500 | None | 66 |

| E | Secondary | Production of nutrition, hygiene, and personal care products | 1200 | Ecuador, Central America in the North Triangle, and Peru | 48 |

| Case | Educational Level | Position | Experience (Years) | Interview Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Industrial engineer | Planner and buyer | More than 4 | 11 January 2022 |

| B | Industrial engineer | Programming manager of production | More than 3 | 28 January 2022 |

| C | Marketing specialist | Technical advisor in the central region of the country | More than 4 | 21 January 2022 |

| D | Industrial engineer | Demand planning analyst | More than 8 | 13 January 2022 |

| E | Industrial engineer | Production supervisor | More than 6 | 19 January 2022 |

| CASE | Stimuli | Detection | Planning | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Increased demand for antiseptic alcohol, dietary supplements, and antibacterial gel | Increased product sales units Inventory rotation | Development of a new product | Business objectives and those of each area |

| Increase in production capacity through overtime | ||||

| Increased maintenance frequency | ||||

| Agreement with suppliers on modification in quantity and date of supply | ||||

| Work absenteeism | Lack of staff on the lines of production | Staff loan between production lines | Days of absenteeism per worker staff turnover | |

| Increased disabilities due to the spread of COVID-19 | Extension of work shifts | |||

| Mobility restrictions | Staff training | |||

| B | Increased demand for ready-to-assemble desks | Pending orders | Increased production capacity through overtime, hiring of personnel in production processes and product packaging | Production costs Billing level Production indicators Brand recognition by clients |

| Increased frequency and quantities of supply | ||||

| Increased supplier production capacity | ||||

| New production plant | ||||

| New distribution center | ||||

| Outsource production | ||||

| Purchase of machinery | ||||

| Implementation of online sales and service channels | ||||

| Salary bonus to production and logistics staff | ||||

| Work absenteeism | Lack of staff on the lines of production | Extension of work shifts | Days of absenteeism per worker Productivity per worker Work-attending days | |

| Increased disabilities due to the spread of COVID-19 | Staff training | |||

| Mobility restrictions | Increased staff availability | |||

| C | Increased demand for beds in intensive care units in Colombian hospitals | Increased occupancy levels of intensive care beds in Colombian hospitals Government request to increase the capacity of intensive care rooms in Colombian hospitals | Design and development of intensive care beds | Product launch time Cost of holding inventory Failures in the product design and the development process |

| Loss of contact with the end customer and with shop assistants | Increased warranty claims Increased complaints and claims | Design and development of online tutorials, which show cutting and assembling products. | Decrease in warranty cost Decrease in requests, complaints, suggestions, and claims | |

| D | Increased demand for antiseptic alcohol, and antibacterial gel | Increased product sales Information provided at the point of sale | Supply at the distribution center, at the point of sale, or direct delivery to the customer | Fulfillment of the promise Product delivery Return indicator, destruction indicator, supply indicator, service level indicator, on time delivery indicator, on time in full, out of stock indicator, excess indicator, and inventory level indicator |

| Decreased demand for the products that improve digestion | Decreased product sales Information provided at the point of sale | Supply renegotiation Product destruction Product return | ||

| Change in the way of purchasing products | Increased sales by online channels | Availability of the website Order traceability | Sales comparison by traditional channels versus online channels | |

| E | 8 g packets of tomato sauce, mayonnaise, and pink sauce in places such as restaurants and cafes | Change in the law that deals with the presentation of 8 g products in restaurants and cafeterias Increased demand for products packaged in 8 g sachets. | Supplying an increase in production capacity by extending work shifts and overtime | Compliance with the production schedule Production indicators |

| Work absenteeism | Lack of staff on the production lines | Staff training | Days of absenteeism per worker Work-attending days | |

| Increased disabilities due to the spread of COVID-19 | Increase in staff availability | |||

| Mobility restrictions | Certification for personnel handling the machines |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz Pacheco, R.A.; Benedito, E. Supply Chain Response during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multiple-Case Study. Processes 2023, 11, 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11041218

Díaz Pacheco RA, Benedito E. Supply Chain Response during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multiple-Case Study. Processes. 2023; 11(4):1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11041218

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz Pacheco, Raúl Antonio, and Ernest Benedito. 2023. "Supply Chain Response during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multiple-Case Study" Processes 11, no. 4: 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11041218

APA StyleDíaz Pacheco, R. A., & Benedito, E. (2023). Supply Chain Response during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multiple-Case Study. Processes, 11(4), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11041218