Advancing Energy Recovery: Evaluating Torrefaction Temperature Effects on Food Waste Properties from Fruit and Vegetable Processing

Abstract

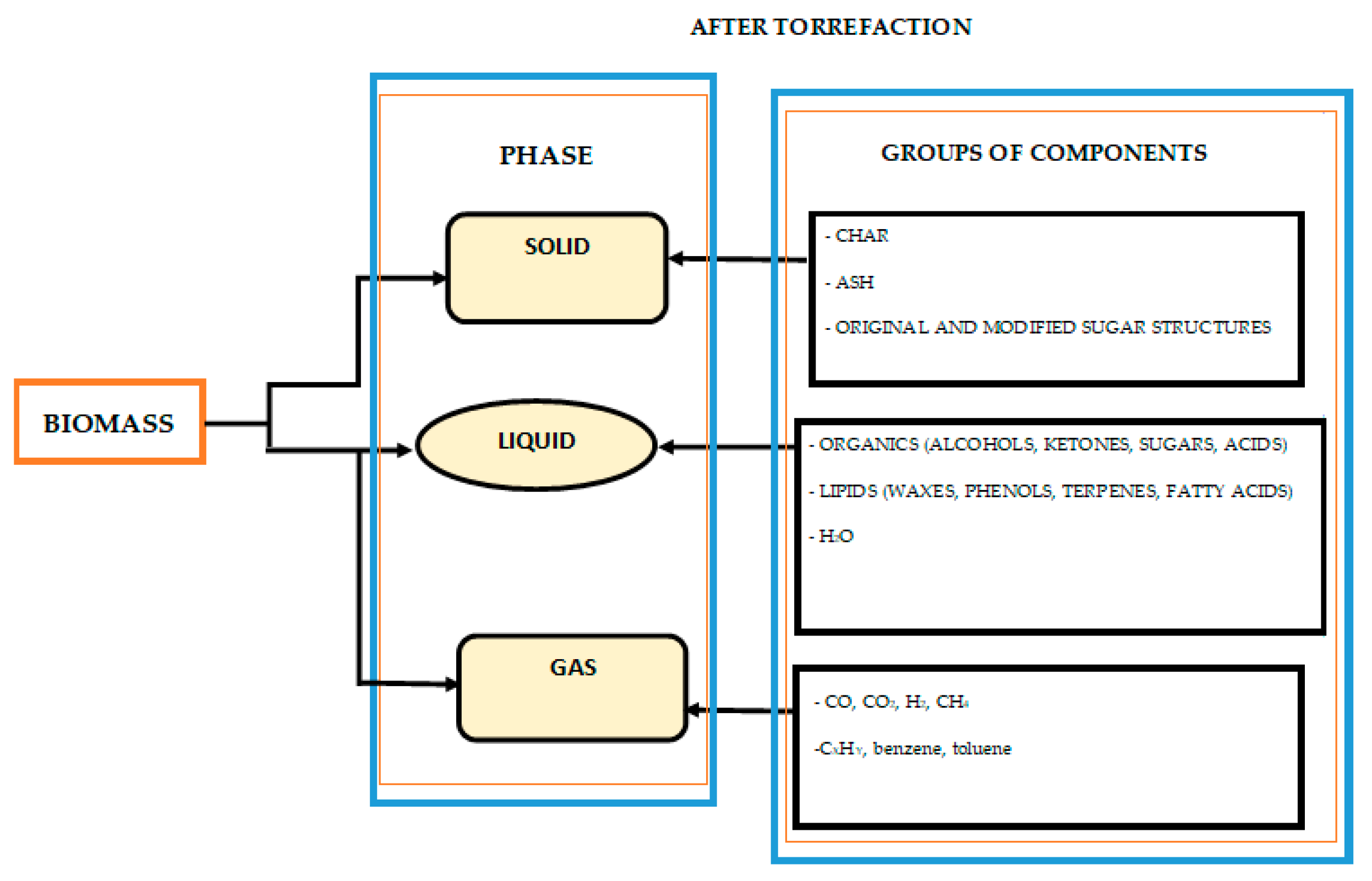

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

2.2. Torrefaction Experiments

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Higher Heating Value Analysis, Mass Yield and Energy Yield

- mr = weight of the raw sample;

- mt = weight of the torrefied sample.

2.3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

3. Results and Discussion

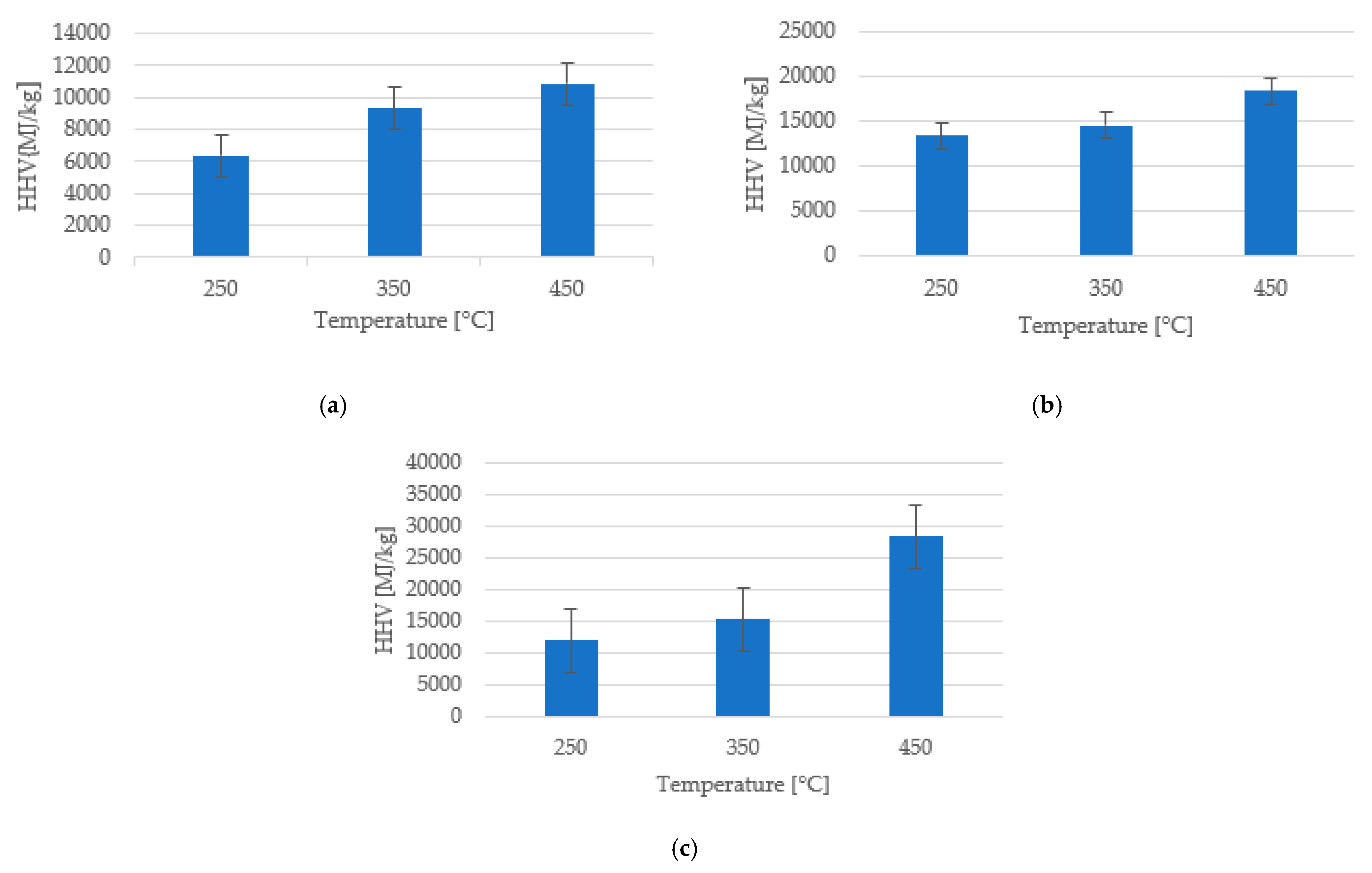

3.1. Parameters for the Efficiency of the Torrefaction Process

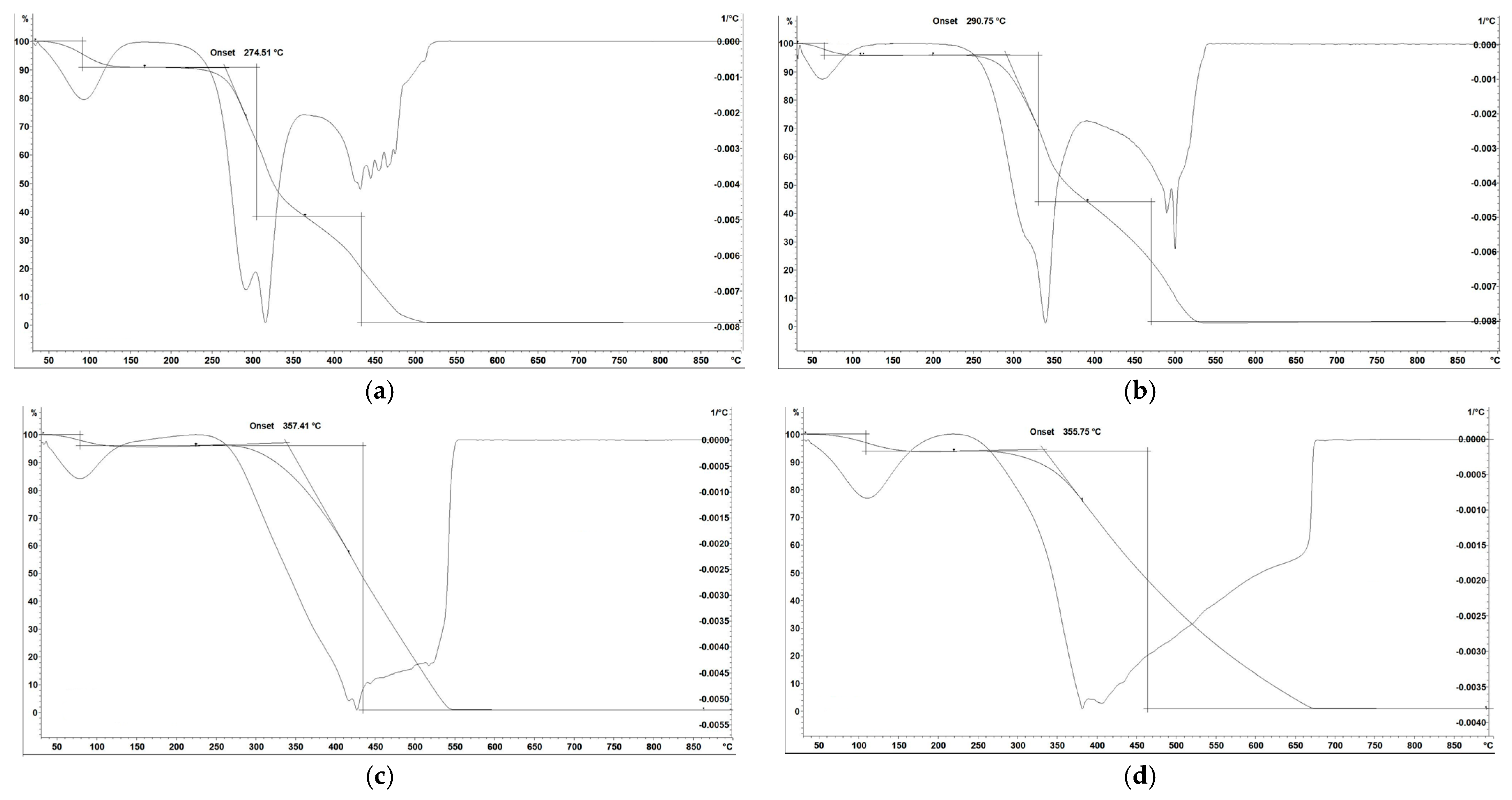

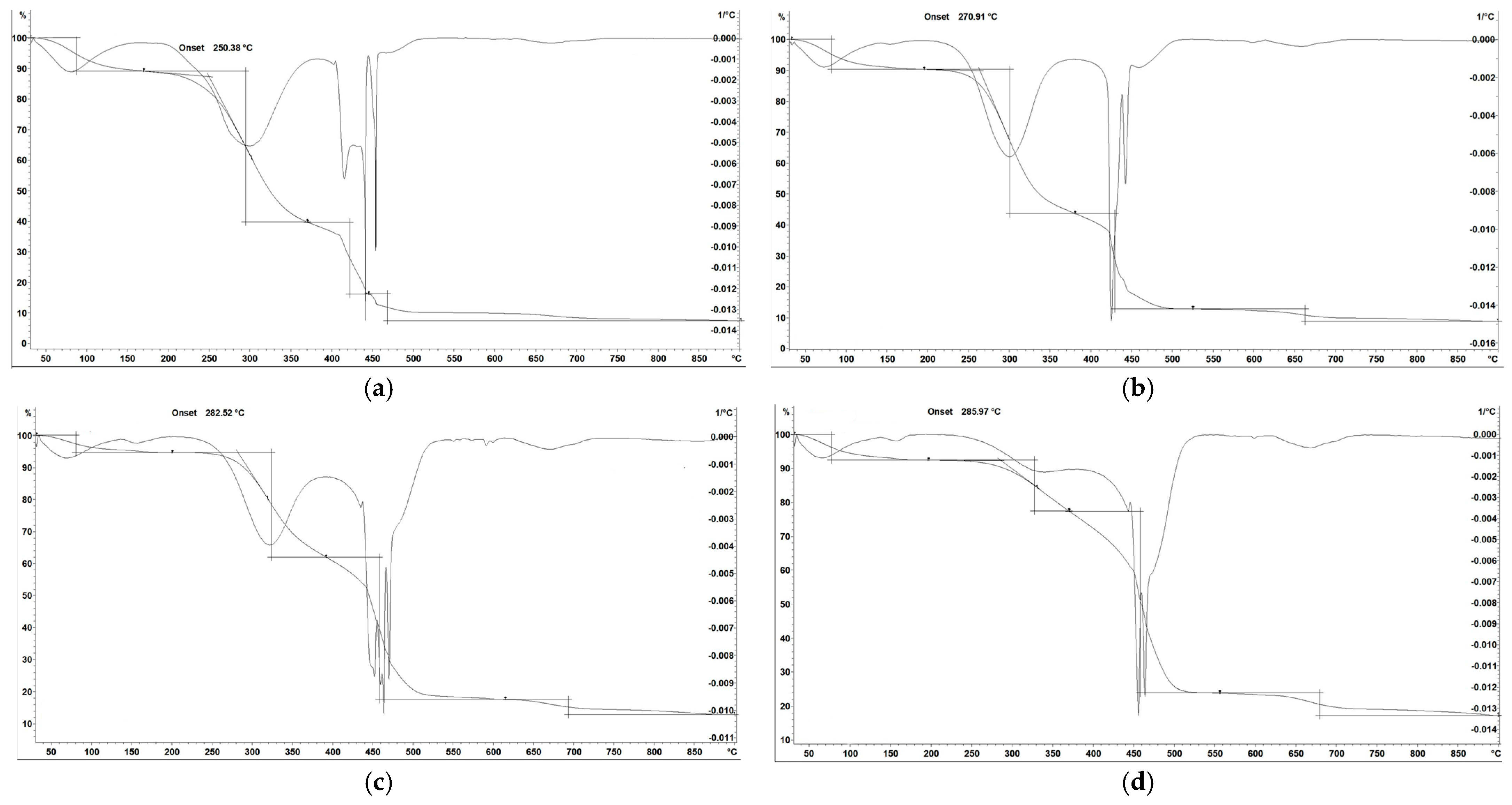

3.2. TGA/DTG Analysis

3.3. Hydrophobicity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATR | Attenuated total reflection |

| DTG | Derivative thermogravimetric |

| ED | Energy density |

| EF | Enhancement factor |

| EY | Energy yield |

| FC | Fixed carbon |

| FR | Fuel ratio |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| FW | Food waste |

| HHV | Higher heating value |

| MY | Mass yield |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| WL | Weight loss |

References

- Orisaleye, J.I.; Jekayinfa, S.O.; Pecenka, R.; Ogundare, A.A.; Akinseloyin, M.O.; Fadipe, O.L. Investigation of the Effects of Torrefaction Temperature and Residence Time on the Fuel Quality of Corncobs in a Fixed-Bed Reactor. Energies 2022, 15, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyjakon, A.; Noszczyk, T.; Smędzik, M. The Influence of Torrefaction Temperature on Hydrophobic Properties of Waste Biomass from Food Processing. Energies 2019, 12, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Ahmmed, R.; Ahsan, S.M.; Rana, J.; Ghosh, M.K.; Nandi, R. A Comprehensive Review of Food Waste Valorization for the Sustainable Management of Global Food Waste. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kende, Z.; Piroska, P.; Szemők, G.E.; Khaeim, H.; Sghaier, A.H.; Gyuricza, C.; Tarnawa, Á. Optimizing Water, Temperature, and Density Conditions for In Vitro Pea (Pisum sativum L.) Germination. Plants 2024, 13, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, F.; Voukkali, I.; Papamichael, I.; Phinikettou, V.; Loizia, P.; Naddeo, V.; Sospiro, P.; Liscio, M.C.; Zoumides, C.; Țîrcă, D.M.; et al. Turning Food Loss and Food Waste into Watts: A Review of Food Waste as an Energy Source. Energies 2024, 17, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, S.E.; Mahamood, R.M.; Jen, T.-C.; Loha, C.; Akinlabi, E.T. An Overview of Biomass Solid Fuels: Biomass Sources, Processing Methods, and Morphological and Microstructural Properties. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2023, 8, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.; Nogueiro, D.; Pizarro, C.; Matos, M.; Bueno, J.L. Non-Oxidative Torrefaction of Biomass to Enhance Its Fuel Properties. Energy 2018, 158, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchpole, O.; Tallon, S.; Dyer, P.; Montanes, F.; Moreno, T.; Vagi, E.; Eltringham, W.; Billakanti, J. Integrated Supercritical fluid extraction and Bioprocessing. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 8, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, P.A.; Carr, M.A.; Kim, S.S.; Beautyman, M.J. Energy Recovery from Waste Food by Combustion or Gasification with the Potential for Regenerative Dehydration: A Case Study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. A Review of the Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass Waste for Hydrochar Formation: Process Conditions, Fundamentals, and Physicochemical Properties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, P.; Raja, V.; Dutta, S.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Food Waste Valorisation via Gasification—A Review on Emerging Concepts, Prospects and Challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 157955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveed, M.H.; Gul, J.; Khan, M.N.A.; Naqvi, S.R.; Štěpanec, L.; Ali, I. Torrefied Biomass Quality Prediction and Optimization Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2024, 19, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, P.; Boersma, A.; Zwart, R.; Kiel, J. Torrefaction for Biomass Co-Firing in Existing Coal-Fired Power Stations; Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands ECN: Petten, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovski, M.; Goričanec, D.; Urbancl, D. The Evaluation of Torrefaction Efficiency for Lignocellulosic Materials Combined with Mixed Solid Wastes. Energies 2023, 16, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.C.; Yu, K.L.; Chen, W.-H.; Pillejera, M.K.; Bi, X.; Tran, K.-Q.; Pétrissans, A.; Pétrissans, M. Variation of Lignocellulosic Biomass Structure from Torrefaction: A Critical Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.U.; Sadiq, K.; Anis, M.; Hussain, G.; Usman, M.; Fouad, Y.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Fayaz, H.; Silitonga, A.S. Turning Trash into Treasure: Torrefaction of Mixed Waste for Improved Fuel Properties. A Case Study of Metropolitan City. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Râpă, M.; Darie-Niță, R.N.; Coman, G. Valorization of Fruit and Vegetable Waste into Sustainable and Value-Added Materials. Waste 2024, 2, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.M.C.; Godina, R.; Matias, J.C.D.O.; Nunes, L.J.R. Future Perspectives of Biomass Torrefaction: Review of the Current State-Of-The-Art and Research Development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazar-Ruiz, A.; Dorado, F.; Sanchez-Silva, L. Influence of Temperature and Residence Time on Torrefaction Coupled to Fast Pyrolysis for Valorizing Agricultural Waste. Energies 2022, 15, 7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głód, K.; Lasek, J.A.; Supernok, K.; Pawłowski, P.; Fryza, R.; Zuwała, J. Torrefaction as a Way to Increase the Waste Energy Potential. Energy 2023, 285, 128606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI EN 14918:2019; Solid Recovered Fuels—Method for the Determination of Calorific Value. UNI: Milano, Italy, 2019.

- ASTM DIN 51900; Determining the Gross Calorific Value of Solid and Liquid Fuels Using the Bomb Calorimeter, and Calculation of Net Calorific Value—Part 1: General Information. DIN: Berlin, Germany, 2000.

- ISO 1928; Solid Mineral Fuels—Determination of Gross Calorific Value by the Bomb Calorimeter and Calculation of the Net Calorific Value. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Mamvura, T.A.; Pahla, G.; Muzenda, E. Torrefaction of Waste Biomass for Application in Energy Production in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, B.R. Slow Pyrolysis of Agro-Food Waste to Produce Biochar and Activated Carbon for Adsorption of Pollutants from Model Wastewater. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călin, C.; Sîrbu, E.-E.; Tănase, M.; Győrgy, R.; Popovici, D.R.; Banu, I. A Thermogravimetric Analysis of Biomass Conversion to Biochar: Experimental and Kinetic Modeling. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhalifa, S.; Mariyam, S.; Mackey, H.R.; Al-Ansari, T.; McKay, G.; Parthasarathy, P. Pyrolysis Valorization of Vegetable Wastes: Thermal, Kinetic, Thermodynamics, and Pyrogas Analyses. Energies 2022, 15, 6277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Wright, C.T.; Boardman, R.D.; Kremer, T. Proximate and Ultimate Compositional Changes in Corn Stover during Torrrefaction Using Thermogravimetric Analyzer and Microwaves. In Proceedings of the 2012, Dallas, TX, USA, 29 July–1 August 2012; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.-J.; Silveira, E.A.; Colin, B.; Chen, W.-H.; Pétrissans, A.; Rousset, P.; Pétrissans, M. Prediction of Higher Heating Values (HHVs) and Energy Yield during Torrefaction via Kinetics. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, R.; Gonçalves, M.; Nobre, C.; Mendes, B. Impact of Torrefaction and Low-Temperature Carbonization on the Properties of Biomass Wastes from Arundo Donax L. and Phoenix Canariensis. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 223, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Liu, F. Prediction of Fuel Properties of Torrefied Biomass Based on Back Propagation Neural Network Hybridized with Genetic Algorithm Optimization. Energies 2023, 16, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebode, W.A.; Ogunsuyi, H.O. Impact of Torrefaction Process Temperature on the Energy Content and Chemical Composition of Stool Tree (Alstonia Congenisis Engl) Woody Biomass. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, M.; Vlassa, M.; Petean, I.; Țăranu, I.; Marin, D.; Perhaiță, I.; Prodan, D.; Borodi, G.; Dragomir, C. Structural Characterization and Bioactive Compound Evaluation of Fruit and Vegetable Waste for Potential Animal Feed Applications. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardick, C.D.; Callahan, A.M.; Chiozzotto, R.; Schaffer, R.J.; Piagnani, M.C.; Scorza, R. Stone Formation in Peach Fruit Exhibits Spatial Coordination of the Lignin and Flavonoid Pathways and Similarity to Arabidopsisdehiscence. BMC Biol. 2010, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatani, A.M.N.; Suh, J.H.; Auger, J.; Alabasi, K.M.; Wang, Y.; Segal, M.S.; Dahl, W.J. Pea Hull Fiber Supplementation Does Not Modulate Uremic Metabolites in Adults Receiving Hemodialysis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1179295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Ye, S.-C.; Sheen, H.-K. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Sugarcane Bagasse via Wet Torrefaction in Association with Microwave Heating. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 118, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Ramos, R.; Valdez Salas, B.; Montero Alpírez, G.; Coronado Ortega, M.A.; Curiel Álvarez, M.A.; Tzintzun Camacho, O.; Beleño Cabarcas, M.T. Torrefaction under Different Reaction Atmospheres to Improve the Fuel Properties of Wheat Straw. Processes 2023, 11, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvis Sandoval, D.E.; Lozano Pérez, A.S.; Guerrero Fajardo, C.A. Pea Pod Valorization: Exploring the Influence of Biomass/Water Ratio, Particle Size, Stirring, and Catalysts on Chemical Platforms and Biochar Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.T.; Freitas, A.; Yang, X.; Hiibel, S.; Lin, H.; Coronella, C. Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC) of Cow Manure: Carbon and Nitrogen Distributions in HTC Products. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2016, 35, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.Y.; Ong, H.C.; Ling, T.C.; Chen, W.-H.; Chong, C.T. Torrefaction of De-Oiled Jatropha Seed Kernel Biomass for Solid Fuel Production. Energy 2019, 170, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, K.D. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy as a Tool for Identifying the Unique Characteristic Bands of Lipid in Oilseed Components: Confirmed via Ethiopian Indigenous Desert Date Fruit. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovski, M.; Goricanec, D.; Krope, J.; Urbancl, D. Torrefaction Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Sustainable Solid Biofuel Production. Energy 2022, 240, 122483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewtrakulchai, N.; Wisetsai, A.; Phongaksorn, M.; Thipydet, C.; Jongsomjit, B.; Laosiripojana, N.; Worasuwannarak, N.; Pimsamarn, J.; Jadsadajerm, S. Parametric Study on Mechanical-Press Torrefaction of Palm Oil Empty Fruit Bunch for Production of Biochar. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2024; 100285, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, R.; Sun, K.; Jiang, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Study on the Effect of Torrefaction on Pyrolysis Kinetics and Thermal Behavior of Cornstalk Based On a Combined Approach of Chemical and Structural Analyses. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 13789–13800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, M.; Khaerudini, D.S.; Chew, J.J.; Sunarso, J. Wet Torrefaction of Empty Fruit Bunches (EFB) and Oil Palm Trunks (OPT): Effects of Process Parameters on Their Physicochemical and Structural Properties. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 35, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimsamarn, J.; Kaewtrakulchai, N.; Wisetsai, A.; Mualchontham, J.; Muidaeng, N.; Jiraphothikul, P.; Autthanit, C.; Eiad-Ua, A.; Laosiripojana, N.; Jadsadajerm, S. Torrefaction of Durian Peel in Air and N2 Atmospheres: Impact on Chemical Properties and Optimization of Energy Yield Using Multilevel Factorial Design. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallampati, R.; Valiyaveettil, S. Apple Peels—A Versatile Biomass for Water Purification? ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 4443–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovski, M.; Petrovič, A.; Goričanec, D.; Urbancl, D.; Simonič, M. Exploring the Properties of the Torrefaction Process and Its Prospective in Treating Lignocellulosic Material. Energies 2023, 16, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zheng, Z.; Fu, K.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, J.; Lu, M. Torrefaction of Biomass Stalk and Its Effect on the Yield and Quality of Pyrolysis Products. Fuel 2015, 159, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Lin, B.-J.; Colin, B.; Chang, J.-S.; Pétrissans, A.; Bi, X.; Pétrissans, M. Hygroscopic Transformation of Woody Biomass Torrefaction for Carbon Storage. Appl. Energy 2018, 231, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Ghiasi, B.; Soelberg, N.R.; Sokhansanj, S. Biomass Torrefaction Process, Product Properties, Reactor Types, and Moving Bed Reactor Design Concepts. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 728140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grycova, B.; Pryszcz, A.; Krzack, S.; Klinger, M.; Lestinsky, P. Torrefaction of Biomass Pellets Using the Thermogravimetric Analyser. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 11, 2837–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.A.R.; Silva, A.M.S.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Nunes, F.M.; Wessel, D.F.; Cardoso, S.M.; Coimbra, M.A. The Hydrophobic Polysaccharides of Apple Pomace. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 223, 115132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyjakon, A.; Noszczyk, T.; Sobol, Ł.; Misiakiewicz, D. Influence of Torrefaction Temperature and Climatic Chamber Operation Time on Hydrophobic Properties of Agri-Food Biomass Investigated Using the EMC Method. Energies 2021, 14, 5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, T.C.; Coronella, C.J.; Vasquez, V.R. Effect of Thermal Pretreatment on Equilibrium Moisture Content of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 4849–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniwal, A.; Sangwan, V.; Punia, D.; Savita, V.S. Pea Shells (Pisum sativum L.) Powder: A Study on physiochemical, in vitro Digestibility and Phytochemicals Screening. Multilogic Sci. 2022, XII, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikhiev, I.G.; Kraysman, N.V.; Sverguzova, S.V. Review of Peach (Prúnus Pérsica) Shell Use to Remove Pollutants from Aquatic Environments. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2024, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, V.; Khayet, M.; Montero-Prado, P.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Liakopoulos, G.; Karabourniotis, G.; Del Río, V.; Domínguez, E.; Tacchini, I.; Nerín, C.; et al. New Insights into the Properties of Pubescent Surfaces: Peach Fruit as a Model. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 2098–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Ttor (°C) | HHV (kJ/kg) ±3% | WL (%) | MY (%) | EY (%) | Enhancement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pea shells | Raw | 4.811 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1.00 |

| 250 | 6.366 | 15.94 | 74.05 | 97.75 | 1.32 | |

| 350 | 9.307 | 47.44 | 50.55 | 97.56 | 1.93 | |

| 450 | 10.888 | 63.38 | 36.61 | 82.73 | 2.26 | |

| Apple peels | Raw | 10.019 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1.00 |

| 250 | 12.098 | 33.54 | 66.45 | 80.40 | 1.21 | |

| 350 | 15.346 | 51.79 | 48.20 | 73.74 | 1.53 | |

| 450 | 28.481 | 66.03 | 33.96 | 96.44 | 2.84 | |

| Peach pits | Raw | 11.898 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1.00 |

| 250 | 13.352 | 21.47 | 89.08 | 99.76 | 1.12 | |

| 350 | 14.531 | 48.10 | 51.89 | 63.30 | 1.22 | |

| 450 | 18.370 | 7.91 | 38.35 | 59.05 | 1.54 |

| Sample | Ti (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tb (°C) | Moisture Content (%) | Volatile Matter Contents (%) | Ash Content (%) | Fixed Carbon Content (%) | Fuel Ratio (FR) (/) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pea shells | ||||||||

| Raw | 250.4 | 290.2 | 469.8 | 7.06 | 91.39 | 7.4 | 0.01 | 0.0001 |

| 250 °C | 270.9 | 301.3 | 525.2 | 6.79 | 92.15 | 7.8 | 0.05 | 0.00054 |

| 350 °C | 282.5 | 320.5 | 520.3 | 6.51 | 87.29 | 12.6 | 0.11 | 0.0013 |

| 450 °C | 285.9 | 330.6 | 510.3 | 6.39 | 81.50 | 18.3 | 0.20 | 0.0024 |

| Apple peels | ||||||||

| Raw | 194.6 | 225.4 | 505.2 | 7.11 | 98.47 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 250 °C | 278.7 | 308.2 | 560.1 | 5.15 | 93.94 | 3.2 | 2.86 | 0.031 |

| 350 °C | 295.06 | 332.1 | 550.3 | 4.45 | 83.38 | 5.3 | 11.32 | 0.136 |

| 450 °C | 306.69 | 350.1 | 561.2 | 4.34 | 63.91 | 7.3 | 28.79 | 0.403 |

| Peach pits | ||||||||

| Raw | 274.51 | 290.1 | 510.2 | 5.23 | 94.75 | 0.2 | 5.05 | 0.053 |

| 250 °C | 290.75 | 330.3 | 530.2 | 4.80 | 99.37 | 0.3 | 0.33 | 0.003 |

| 350 °C | 357.41 | 420.2 | 540.8 | 4.02 | 84.23 | 0.7 | 15.07 | 0.179 |

| 450 °C | 355.75 | 395.1 | 670.1 | 3.50 | 61.34 | 1.1 | 37.56 | 0.612 |

| Wavelength (cm−1) | Functional Groups | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3700 | O–H stretching in alcohols | Mostly in raw biomass |

| 3340 | O–H peak in hydroxyl groups | In torrefied samples, a less intense peak |

| 3000–2850 | C–H expansion in alkanes | Loss of aliphatic groups with temperature increase |

| 1710 | C=O | As the temperature increases, it decreases |

| 1630 | Variation of C=O groups | Higher peak at torrefaction temperatures |

| 1513 | C=C expansion of aromatic rings | Stronger with increasing temperature. No change in the raw sample |

| 1315–1000 | Expansion vibrations of CO | Larger peaks in torrefied samples than in raw biomass |

| 1150–1300 | C–H deformation | As the temperature rises, these deformations are increased |

| 770 | C-H vibrations in cellulose | With an increase in temperature |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Škorjanc, A.; Gruber, S.; Rola, K.; Goričanec, D.; Urbancl, D. Advancing Energy Recovery: Evaluating Torrefaction Temperature Effects on Food Waste Properties from Fruit and Vegetable Processing. Processes 2025, 13, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13010208

Škorjanc A, Gruber S, Rola K, Goričanec D, Urbancl D. Advancing Energy Recovery: Evaluating Torrefaction Temperature Effects on Food Waste Properties from Fruit and Vegetable Processing. Processes. 2025; 13(1):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13010208

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠkorjanc, Andreja, Sven Gruber, Klemen Rola, Darko Goričanec, and Danijela Urbancl. 2025. "Advancing Energy Recovery: Evaluating Torrefaction Temperature Effects on Food Waste Properties from Fruit and Vegetable Processing" Processes 13, no. 1: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13010208

APA StyleŠkorjanc, A., Gruber, S., Rola, K., Goričanec, D., & Urbancl, D. (2025). Advancing Energy Recovery: Evaluating Torrefaction Temperature Effects on Food Waste Properties from Fruit and Vegetable Processing. Processes, 13(1), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13010208