Metabolic Regulation Analysis of Ajmalicine Biosynthesis Pathway in Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don Suspension Culture Using Nanosensor

Abstract

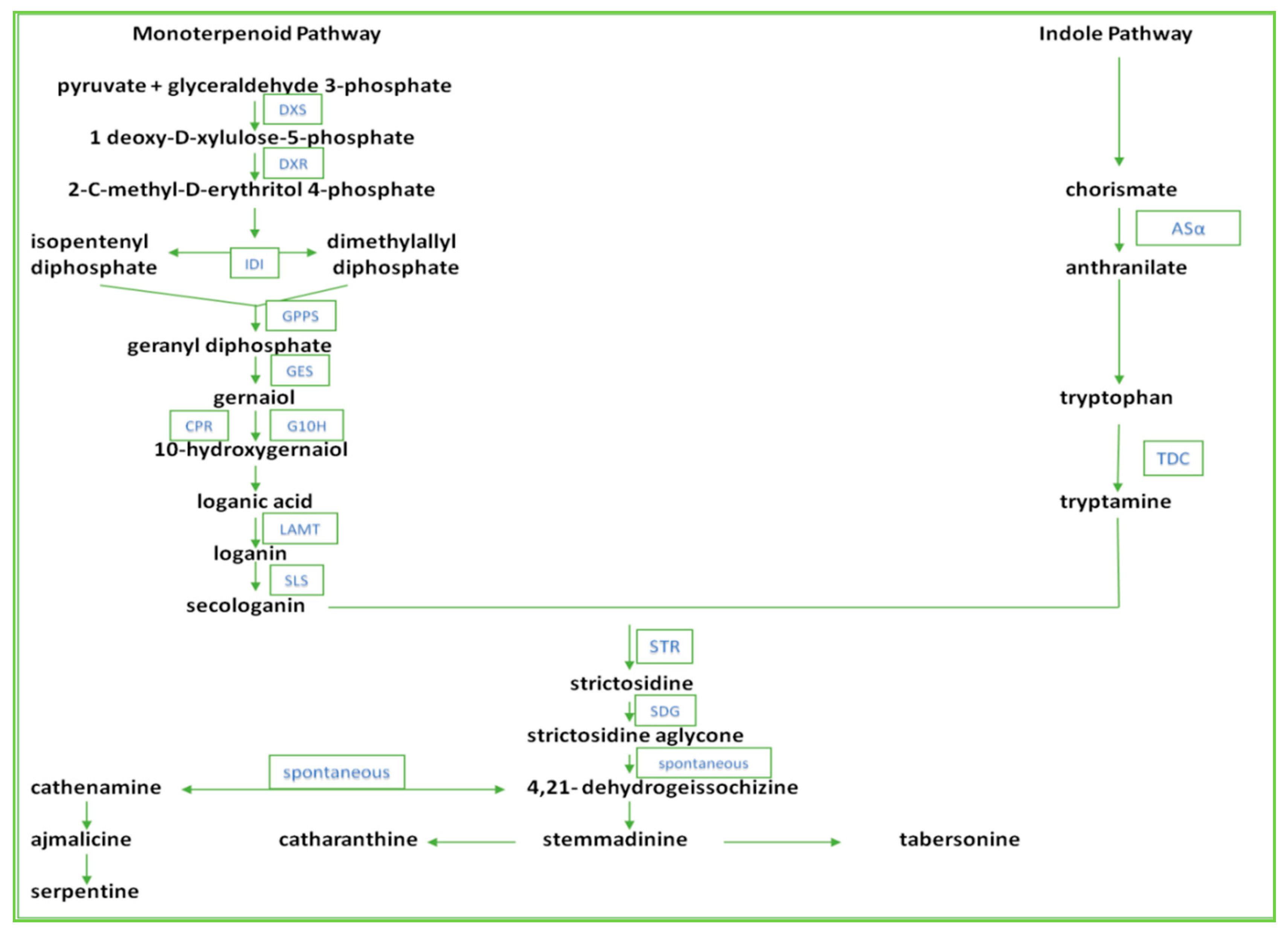

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

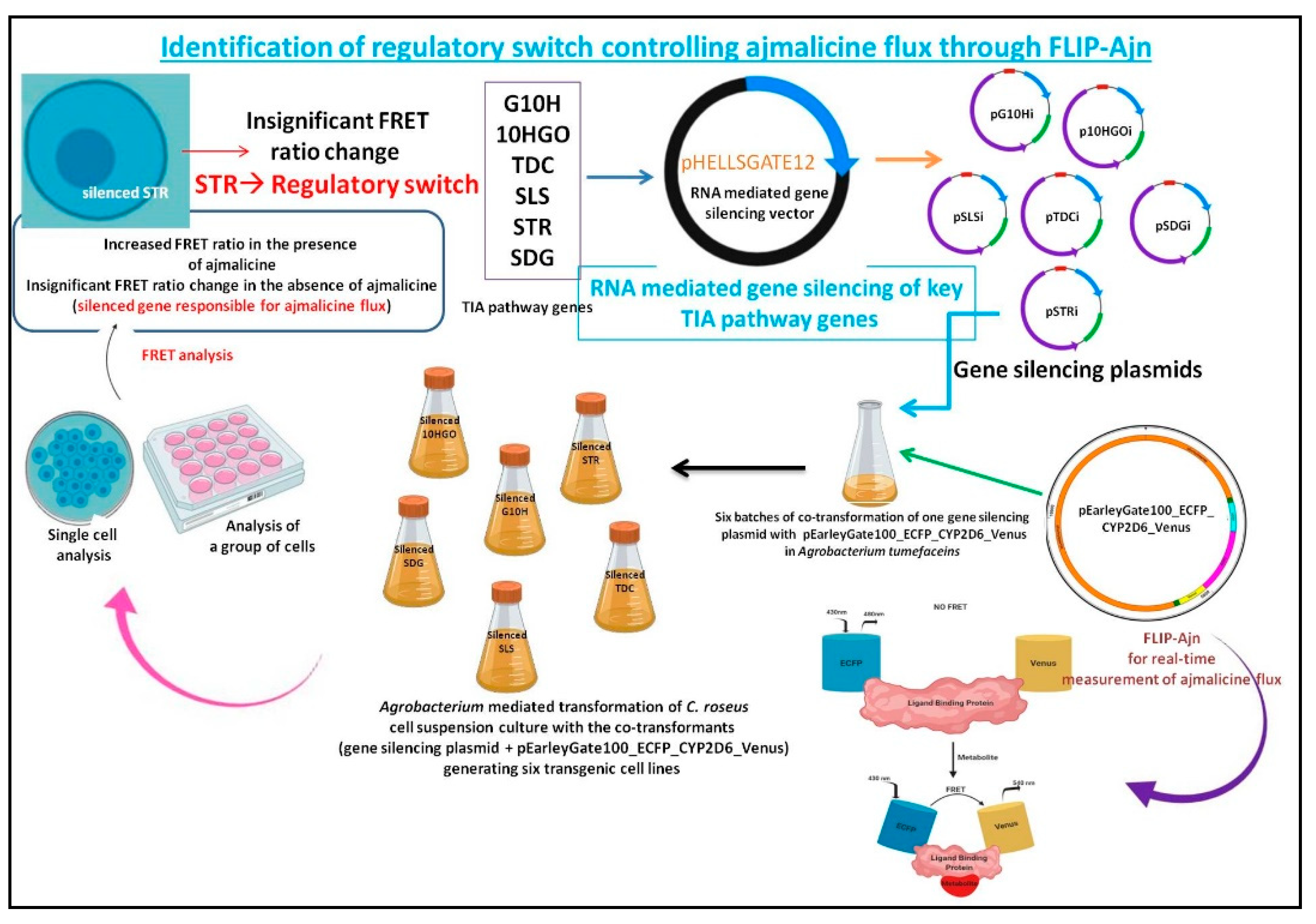

2.1. Development of the TIA Pathway Silenced Lines

2.2. Generation of Transgenic C. roseus Cell Lines

2.3. Explant

2.4. Transformation and Co-Cultivation

2.5. Elicitation

2.6. FRET Analysis

2.7. PCR Analysis

3. Results

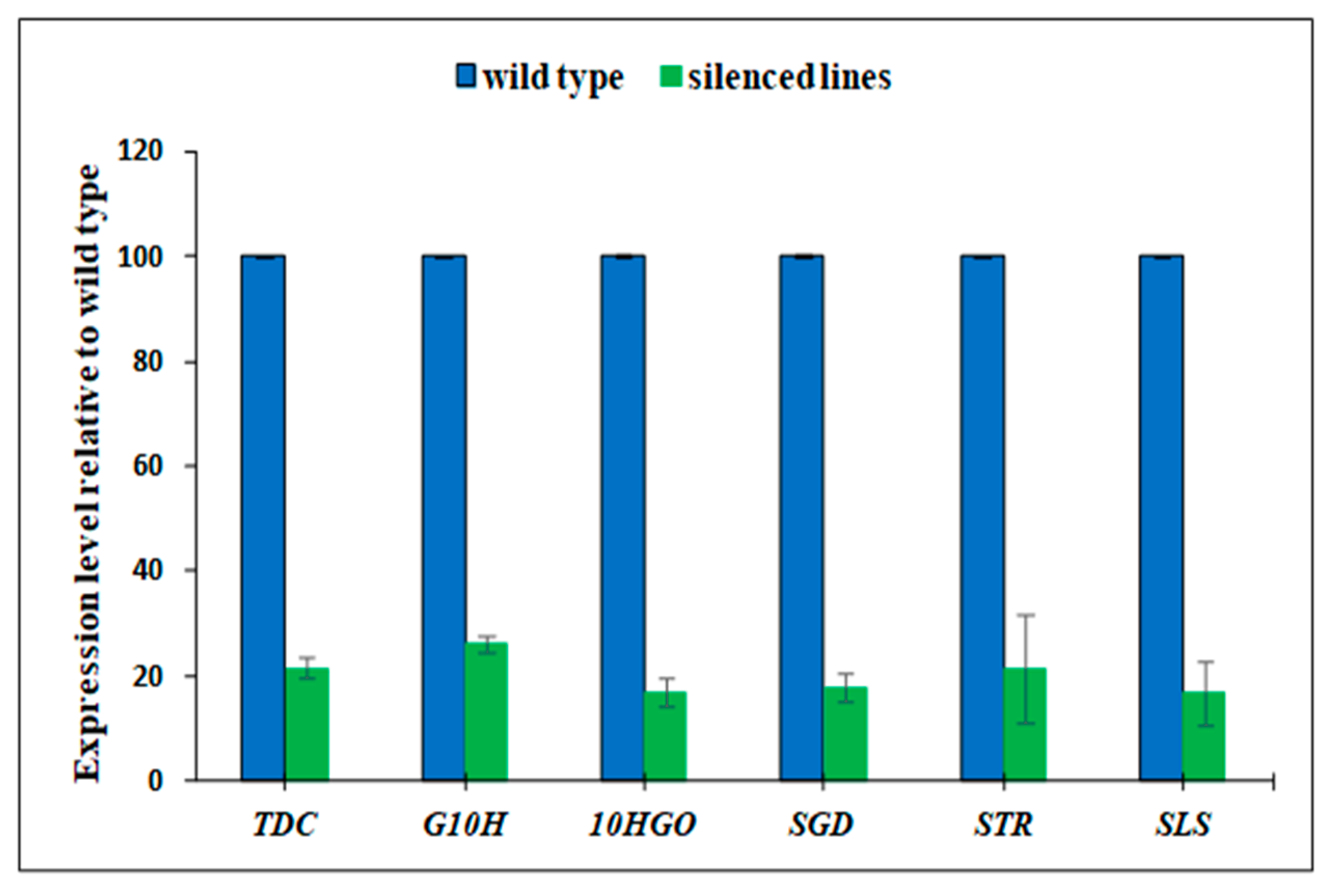

3.1. Gene Silencing and Validation

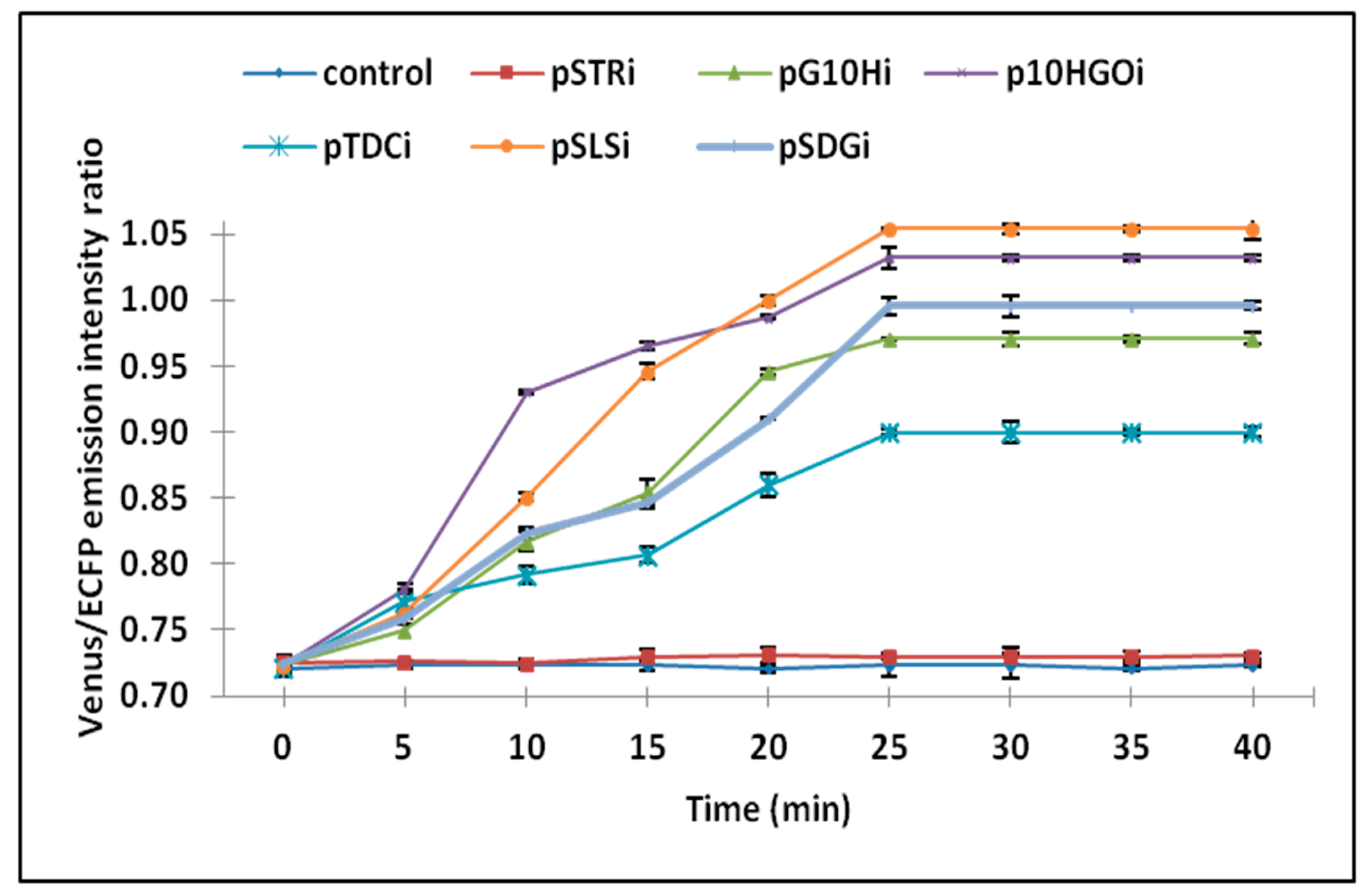

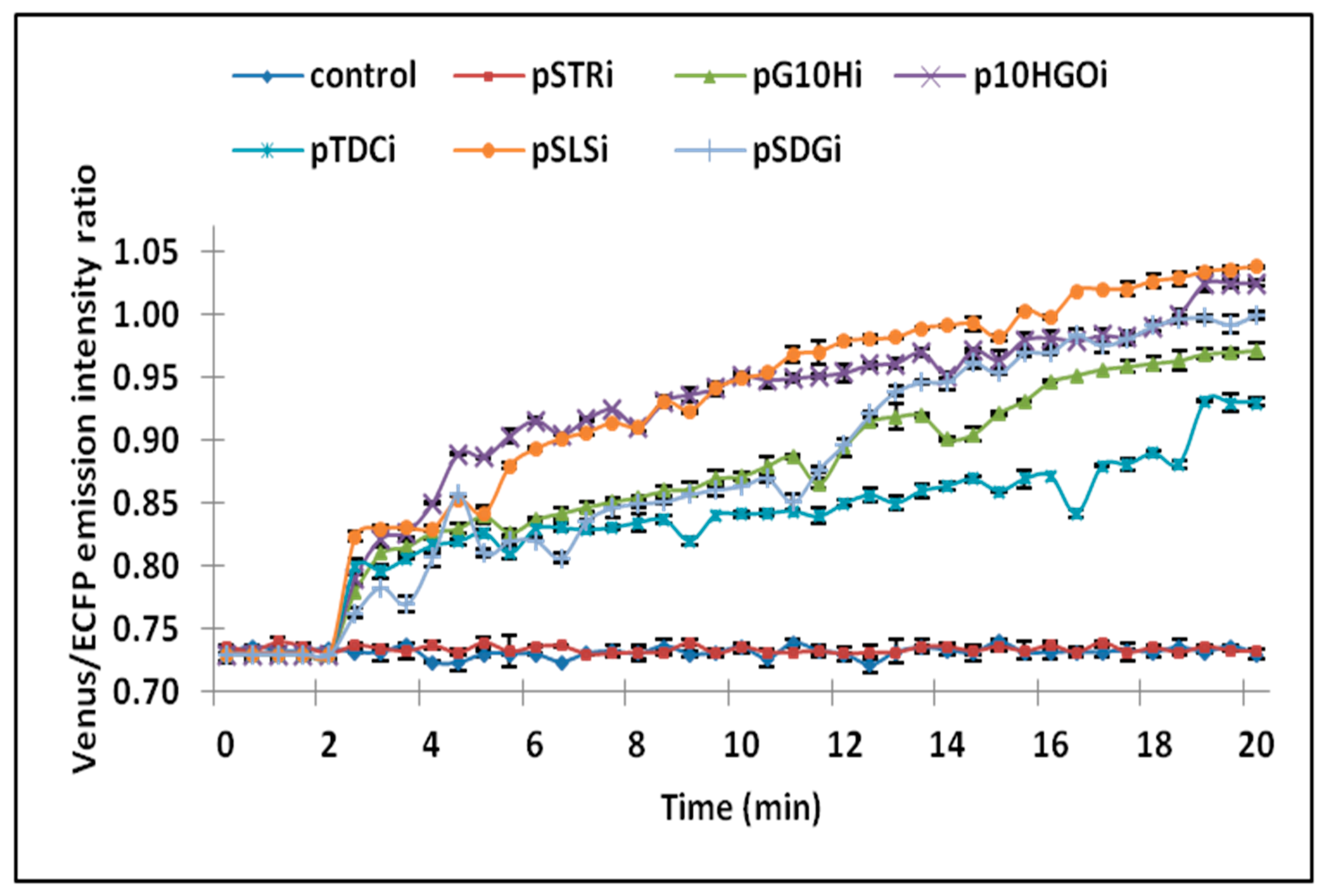

3.2. Analysis of Ajmalicine Dynamics

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fulzele, D.P.; Namdeo, A.G. Cost effective pilot-scale ajmalicine production by Catharanthus roseus cell suspension cultures in a 100 L bioreactor. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.R.; Jena, R.C.; Samal, K.C. Rapid in vitro multiplication of an endangered medicinal plant sarpgandha (Rauwolfia serpentina). Am. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oksman-Caldentey, K.M. Metabolic engineering of terpenoid indole alkaloid pathway in Catharanthus roseus. Planta Med. 2013, 79, WS17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.; Kumar, S.; Luthra, R. Bioconversion of ajmalicine to serpentine in Catharanthus roseus roots. J. Plant Sci. 2006, 1, 340–347. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Satyaprakash, K. Antimicrobial properties of natural products: A review. Pharma. Innov. J. 2018, 7, 532–537. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.; De, J.N. Anti-snake venom botanicals used by the ethnic groups of Purulia District, West Bengal, India. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2012, 18, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, C.A.; Gopi, R.; Manivannan, P.; Sankar, B.; Kishorekumar, A.; Panneerselvam, R. Antioxidant potentials and ajmalicine accumulation in Catharanthus roseus after treatment with giberellic acid. Colloid Surf. B 2007, 60, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, K.P.; Borison, H.L. Comparative effects of various Rauwolfia alkaloids on centrally evoked vasopressor responses. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1957, 119, 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Long, J.; Ma, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Assessment of the therapeutic activity of a combination of almitrine and raubasine on functional rehabilitation following ischaemic stroke. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2004, 20, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, P.G.; Passmore, P.A. The renin-angiotensin system and antihypertensive drugs in Alzheimer’s disease: Current standing of the angiotensin hypothesis? J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 30, S251–S268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wu, M. Cadmium treatment enhances the production of alkaloid secondary metabolites in Catharanthus roseus. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro, L.; Perez, A.L.; Pedreño, M.A. New method to enhance ajmalicine production in cell cultures based on the use of cyclodextrins. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 33, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, A.; Amin, D.; Sankaranarayanan, A.; Arora, R.; Mathur, A.K. Present status of Catharanthus roseus monoterpenoid indole alkaloids engineering in homo-and hetero-logous systems. Biotechnol. Lett. 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Pandey, S.S.; Shanker, K.; Kalra, A. Endophytes enhance the production of root alkaloids ajmalicine and serpentine by modulating the terpenoid indole alkaloid pathway in Catharanthus roseus roots. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 1128–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Sharma, S.; Misra, P. Elicitation based enhancement of secondary metabolites in Rauwolfia serpentina and Solanum khasianum hairy root cultures. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2016, 12, S315. [Google Scholar]

- Paeizi, M.; Karimi, F.; Razavi, K. Changes in medicinal alkaloids production and expression of related regulatory and biosynthetic genes in response to silver nitrate combined with methyl jasmonate in Catharanthus roseus in vitro propagated shoots. Plant Physiol. Biochem 2018, 132, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, J.; Zhu, J.; He, S.; Zhang, W.; Yu, R.; Zi, J.; Song, L.; Huang, X. Effects of β-cyclodextrin and methyl jasmonate on the production of vindoline, catharanthine, and ajmalicine in Catharanthus roseus cambial meristematic cell cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 7035–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, S.; Srivastava, V.; Rahman, L.U.; Kukreja, A.K. Overexpression of a Catharanthus tryptophan decarboxylase (tdc) gene leads to enhanced terpenoid indole alkaloid (TIA) production in transgenic hairy root lines of Rauwolfia serpentina. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. 2013, 115, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Qiu, F.; Chen, M.; Zeng, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, C.; Lan, X.; Wang, Q.; Liao, Z. Engineering the MEP pathway enhanced ajmalicine biosynthesis. Biotechnol. Appl. Bioc. 2014, 61, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Chen, M.; Zeng, L.; Lan, X.; Wang, Q.; Liao, Z. Abscisic acid enhanced ajmalicine biosynthesis in hairy roots of Rauvolfia verticillata by upregulating expression of the MEP pathway genes. Russ. J. Plant Physl. 2014, 61, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, A.S.; Ragab, A.E.; Ibrahim, A.R.S.; Abdel-Mageed, W.S.; Nasr, M.E. Cloning and overexpression of strictosidine β-D-glucosidase gene short sequence from Catharanthus roseus in Escherichia coli. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qu, Y.; Thamm, A.M.; Czerwinski, M.; Masada, S.; Kim, K.H.; Jones, G.; Liang, P.; De Luca, V. Geissoschizine synthase controls flux in the formation of monoterpenoid indole alkaloids in a Catharanthus roseus mutant. Planta 2018, 247, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, J.A.; McKee, A.E.; Keasling, J.D. High-throughput metabolic engineering: Advances in small-molecule screening and selection. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 563–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrin, G.; Ahmad, M.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Hashem, A.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Ahmad, A. Conversion of cytochrome P450 2D6 of human into a FRET-based tool for real-time monitoring of ajmalicine in living cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Runguphan, W.; Maresh, J.J.; O’Connor, S.E. Silencing of tryptamine biosynthesis for production of nonnatural alkaloids in plant culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13673–13678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, H.; Machida, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Mukai, N.; Misawa, M. Accumulation of glutamine by suspension cultures of Symphytum officinale. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1974, 38, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, M.; Frommer, W.B.; Lalonde, S. Visualization of maltose uptake in living yeast cells by fluorescent nanosensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9846–9851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fehr, M.; Lalonde, S.; Lager, I.; Wolff, M.W.; Frommer, W.B. In vivo imaging of the dynamics of glucose uptake in the cytosol of COS-7 cells by fluorescent nanosensors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 19127–19133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, M.; Mohsin, M.; Iqrar, S.; Manzoor, O.; Siddiqi, T.O.; Ahmad, A. Live cell imaging of vitamin B12 dynamics by genetically encoded fluorescent nanosensor. Sens. Actuators B. Chem. 2018, 257, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumoto, S.; Looger, L.L.; Micheva, K.D.; Reimer, R.J.; Smith, S.J.; Frommer, W.B. Detection of glutamate release from neurons by genetically encoded surface-displayed FRET nanosensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8740–8745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lager, I.; Fehr, M.; Frommer, W.B.; Lalonde, S. Development of a fluorescent nanosensor for ribose. FEBS Lett. 2003, 553, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meehan, T.D.; Coscia, C.J. Hydroxylation of geraniol and nerol by a monooxygenase from Vinca rosea. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1973, 53, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Iturbe, P.G.; Galaz-Avalos, R.M.; Loyola-Vargas, V.M. Determination and partial purification of 10-oxogeranial: Iridodial cyclase an enzyme catalyzing the synthesis of iridodial from Catharanthus roseus hairy roots. Phyton 2005, 54, 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, V.; Wiens, B.; Masada-Atsumi, S.; Yu, F.; De Luca, V. 7-deoxyloganetic acid synthase catalyzes a key 3 step oxidation to form 7-deoxyloganetic acid in Catharanthus roseus iridoid biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 2014, 101, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uesato, S.; Ikeda, H.; Fujita, T.; Inouye, H.; Zenk, M.H. Elucidation of iridodial formation mechanism-partial purification and characterization of the novel monoterpene cyclase from Rauwolfia serpentina cell suspension cultures. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 4431–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geu-Flores, F.; Sherden, N.H.; Courdavault, V.; Burlat, V.; Glenn, W.S.; Wu, C.; Nims, E.; Cui, Y.; O’Connor, S.E. An alternative route to cyclic terpenes by reductive cyclization in iridoid biosynthesis. Nature 2012, 492, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmler, S.; Schröder, G.; St-Pierre, B.; Crouch, N.P.; Hotze, M.; Schmidt, J.; Strack, D.; Matern, U.; Schröder, J. Indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus: New enzyme activities and identification of cytochrome P450 CYP72A1 as secologanin synthase. Plant J. 2000, 24, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, V.; Marineau, C.; Brisson, N. Molecular cloning and analysis of cDNA encoding a plant tryptophan decarboxylase: Comparison with animal dopa decarboxylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 2582–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kutchan, T.M. Expression of enzymatically active cloned strictosidine synthase from the higher plant Rauvolfia serpentina in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1989, 257, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, D.H.; Jin, H.B.; Chen, Y.H.; Cui, L.J.; Ren, W.W.; Gong, Y.F.; Tang, K.X. Terpenoid indole alkaloids biosynthesis and metabolic engineering in Catharanthus roseus. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007, 49, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Peebles, C.A. Engineering overexpression of ORCA3 and strictosidine glucosidase in Catharanthus roseus hairy roots increases alkaloid production. Protoplasma 2016, 253, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, F.; Xing, S.; Zhao, J.; Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R.; Tian, Y.; Wang, G.; Tang, K. Overexpression of ORCA3 and G10H in Catharanthus roseus plants regulated alkaloid biosynthesis and metabolism revealed by NMR-metabolomics. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julsing, M.K.; Koulman, A.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Quax, W.J.; Kayser, O. Combinatorial biosynthesis of medicinal plant secondary metabolites. Biomol. Eng. 2006, 23, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, E.; Runguphan, W.; O’Connor, S.; Prather, K.J. Opportunities in metabolic engineering to facilitate scalable alkaloid production. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallard, D.A.C. Transgenic Plant Cells for the Production of Indolealkaloids. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Canel, C.; Lopes-Cardoso, M.I.; Whitmer, S.; van der Fits, L.; Pasquali, G.; van derHeijden, R.; Hoge, J.H.; Verpoorte, R. Effects of over-expression of strictosidine synthase and tryptophan decarboxylase on alkaloid production by cell cultures of Catharanthus roseus. Planta 1998, 205, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goddijn, O.J.; Pennings, E.J.; van der Helm, P.; Schilperoort, R.A.; Verpoorte, R.; Hoge, J.H.C. Overexpression of a tryptophan decarboxylase cDNA in Catharanthus roseus crown gall calluses results in increased tryptomine levels but not in increased terpenoid indole alkaloid production. Transgenic Res. 1995, 4, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.T.; Liu, H.; Gao, X.S.; Zhang, H.X. Overexpression of G10H and ORCA3 in the hairy roots of Catharanthus roseus improves catharanthine production. Plant Cell Rep. 2010, 29, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Manmathan, H.; Sun, C.; Peebles, C.A. Examining the transcriptional response of overexpressing anthranilate synthase in the hairy roots of an important medicinal plant Catharanthus roseus by RNA-seq. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ambrin, G.; Ali, H.M.; Ahmad, A. Metabolic Regulation Analysis of Ajmalicine Biosynthesis Pathway in Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don Suspension Culture Using Nanosensor. Processes 2020, 8, 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8050589

Ambrin G, Ali HM, Ahmad A. Metabolic Regulation Analysis of Ajmalicine Biosynthesis Pathway in Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don Suspension Culture Using Nanosensor. Processes. 2020; 8(5):589. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8050589

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmbrin, Ghazala, Hayssam M. Ali, and Altaf Ahmad. 2020. "Metabolic Regulation Analysis of Ajmalicine Biosynthesis Pathway in Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don Suspension Culture Using Nanosensor" Processes 8, no. 5: 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8050589