Tackling Food Waste in All-Inclusive Resort Hotels in Egypt

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How and why FLW emerges within and across the food service cycle, comprising procurement, menu planning, receiving, storage, preparation, food service and waste disposal?

- What are all-inclusive hotel mangers’ perceptions of the causes of FLW?

- How could FLW be reduced in all-inclusive hotels to the minimum level?

- How do all-inclusive hotels incorporate technological innovations in tackling FLW?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Food Waste and Loss

2.2. FLW in the Hotel Industry

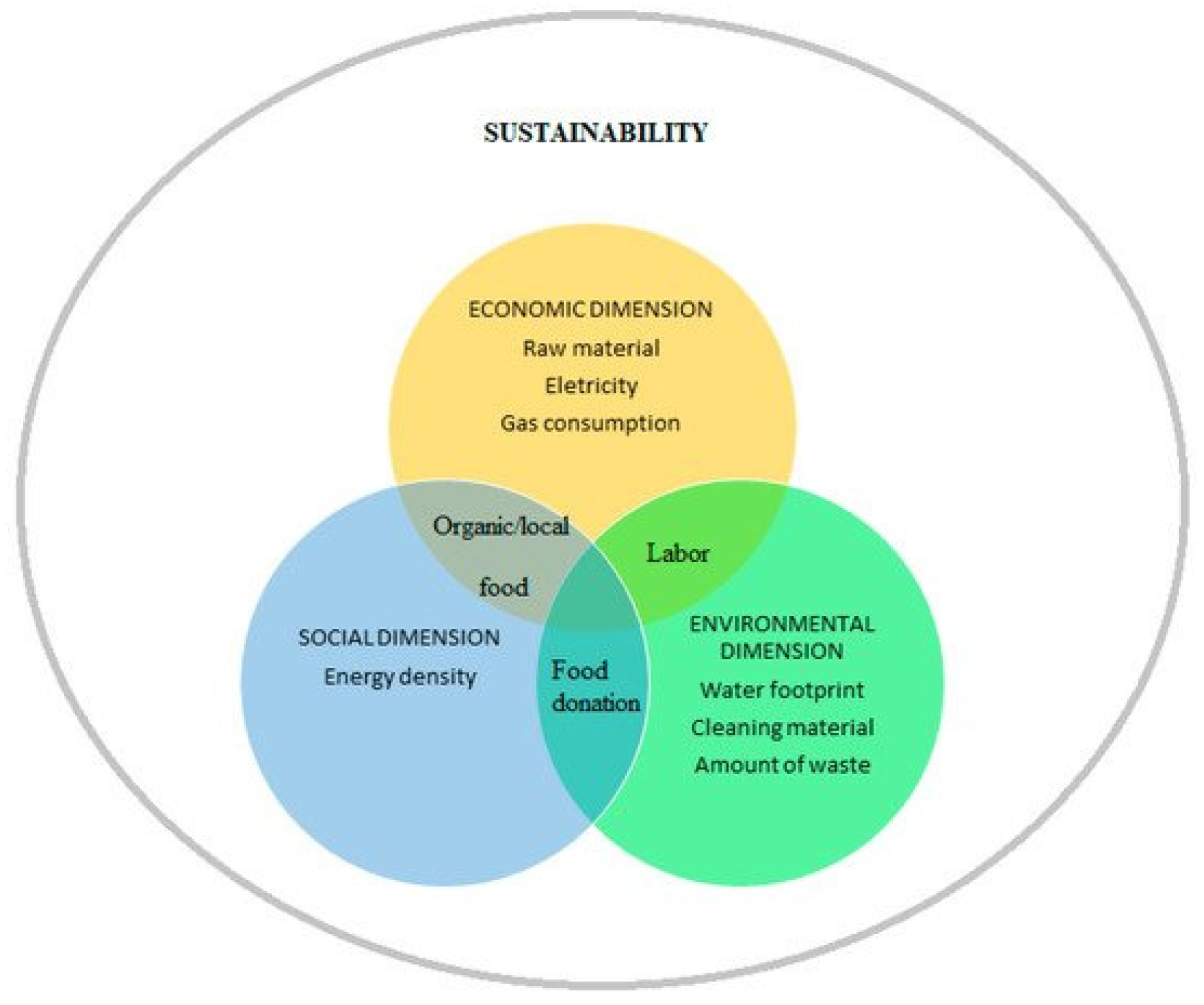

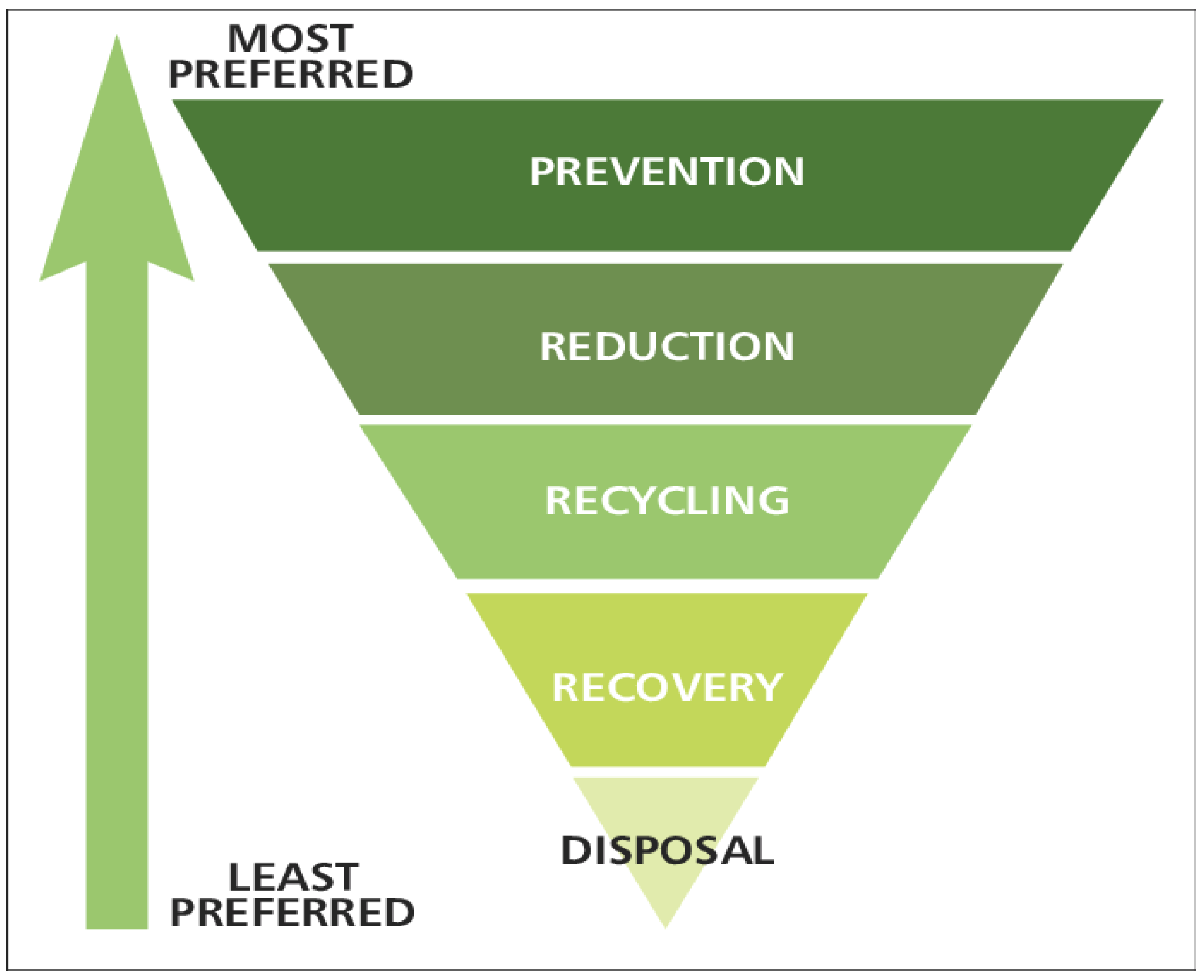

2.3. FLW Management Practices in the Hotel Industry

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Theme One: Management Operation

- The availability of an effective reduction plan

Senior management is required to define many attributes related to tackling food waste such as strategies and practices of reduction, staff hiring, training, and engagement, cascading the reduction culture, and awareness between hotel employees and guests.

- 2.

- Staff hiring process and training

Senior management is responsible to set the strategies to reduce food waste, while hotel employees whom responsible to apply the strategy. In Hurghada, especially in the high summer season we had to recruit enough employees in different hotel departments and usually, they are unqualified enough and there is no available time to train them. Consequently, these employees are the main drivers of food waste in kitchen operation.

In the last five years, the Egyptian hotel industry witnesses’ dramatic circumstances whether a political issue or the impact of COVID-19, therefore, most of the qualified employees shifting their careers. Consequently, we had to hire inexperienced employees with lack many required skills. Moreover, lack of time, as well as training costs, decrease the quality of training courses.

- 3.

- Awareness

There are some sequences to reduce the level of food waste, first, the management must engage hotel employees in their objectives and practices. Second, awareness of the problem and its impact. Third, conducting an effective training and create motivation drive for employees such as bonuses, gifts, salary increases. The fourth, financial penalty for improper practices.

- 4.

- Characteristic of all-inclusive operation

I feel that all-inclusive guests do not care about their level of food consumption since they already paid in advance a fixed price. Also, we have a lot of guest nationalities with different cultural background and eating habits, thus, breakfast, lunch, and dinner buffets have different food items with enough to satisfy the guest. A lot of waste is produced due to the nature of the all-inclusive concept.

During the peak season, the quality of some items may be below guest satisfaction due to the low room rate of all-inclusive hotels, consequently guests will order a different item and the first one will throw into garbage. For example, at my hotel the all-inclusive programs have 3 grades, guest belong to first and second grade are not authorized to consume the imported wine so guests had to test different kinds of local wine. The same situation could happen in a food item, therefore all-inclusive hotels generate more waste food than the traditional one.

- 5.

- Impact of food safety on FLW

- 6.

- Kitchen operations

Compared to our guests, kitchen operations waste less food. I believe that guests waste food between 40–50% of total FLW while kitchen operations might contribute 10–20% by the maximum from total FLW.

4.2. Theme Two: Foodservice Cycle

- Menu Planning

Certainly, menu design has the biggest impact on FLW, especially in all-inclusive hotels. Because all-inclusive main restaurants serve a cyclic menu for buffet. Buffet cyclic menus produce an excessive amount of waste because the surplus cannot be served the next day. On contrary, on ‘a la carte’menus we can manage better menu planning by trying to have a similar menu between different outlets. Admittedly, menus engineering could help to reduce FLW from arising.

Certainly, the low room rate of all-inclusive hotels influences on menu planning, because we are trying as much as possible to avoid the imported items and we are depending on national items. Like these practices increase the level of waste because the European guests haven’t eaten before the local foods hence thy might try to test too many items and vice versa for Egyptian and Arab nationalities.

- 2.

- Food Procurement

Economic and operational reflections rather than sustainability ones chiefly drove purchase decisions. All-inclusive hotels have a high operational cost so savings achieved by a cost-efficient procurement system were valued more than the losses accrued due to wastage.

Because Hurghada city is far away from the capital and food supply company, usually, executive chef ordering extra stocks to minimize the risk of food shortfalls and consequent impact, such this leads to an inability to use surplus stock which increases spoilage waste and purchasing costs especially on the dairy products, vegetables, fruits, and fresh juice.

- 3.

- Receiving and Storage

FLW might occur in the storage stage in few cases such as the poor condition of store equipment, improper food temperature, or in case the storekeeper did not follow standard stock control practices.

- 4.

- Food Production

In all-inclusive hotels, we are serving food around the clock buffet style to serve all in-house guests. Therefore, kitchen staff usually have a stock of cooked food for buffet refile and to avoid food shortfall. at the end of dinner time, we have unconsumed food in the kitchen as well as in the buffet. For hygiene and company quality standard such this is food considers as wastage.

- 5.

- Food Service

Despite the buffet service is more fit and suitable for guests and the F&B team, but the buffet is the main driver of food waste. Buffet should be full of food items up to last minutes, certainly too much food will not be consumed and too much food will go to waste.

4.3. Theme Three: All-Inclusive Employees

- Staff behavior

Chefs must use the entire package of beef when a recipe calls for four and a half kilograms of beef and a package of beef only comes in five kilograms. This act does not come with bad intentions, but it has resulted in a surprising amount of FLW.

In all-inclusive restaurants that offer ‘a la carte’menus, the service team can recommend or guide guests to food quantities that are suitable for them. This is a kind of positive staff attitude to reduce the level of dish waste.

- 2.

- Staff awareness

The hotel management should hire well-educated employees with the required skills. Besides, the senior management has a responsibility toward their employees such as promoting the FLW reduction culture between employees, conducting a sufficient training program, motivate their employees, cascading the awareness’s of the problem, ensuring proper and effective communication between hotel staff, green appraisal …. etc.

4.4. Theme Four: All-Inclusive Guests

- Guest attitude

Egyptian, Arab, and Russian nationality are more food wasteful because they visit the buffet than needed to try different food items further to over-consumed portion size, while the European visitors are less wasteful. Women and seniors are more conscious than men and younger. All of this goes around the clock, the perception is “eat endlessly, serve endless”.

Our visitors come from a variety of cultural backgrounds, which influences their eating habits. They want to eat and drink without worrying about what goes into the garbage because they have paid in advance. If we want to reduce waste in all-inclusive resorts, we need to pay attention to consumer behavior. Adjusting buffet food items according to most of the in-house guest nationality and their desires for food.

- 2.

- Awareness

Certainly, if guests are aware of sustainability and the different impacts of food waste, they will reduce the level of wastage. Proper communication with a guest can be done through awareness Champaigns and other ways such as toolkit for reduction, posters, brochures, and on-table cards. Consequently, guests will reduce their portion size from the buffet and will reduce food surplus.

Guest awareness of environmental and ethical impacts of FLW will change guest consumption behavior. For example, we have a daily announcement of the level of FLW by sign in the main restaurant, so the FLW on buffet has been reduced

4.5. The Common FLW in All-Inclusive Hotels

4.6. Recommendations for Tackling FLW in All-Inclusive Hotels

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

- Track and quantify FLW across the food service cycle, then analyze the reason for waste. Separate and categorize FLW using different colored bins, whether in the kitchen or in restaurants, to identify the most common sections where FLW occurs.

- Buffet service style can be changed to deliver individualized, high-value service. For example, instead, of offering food in chafing dishes, live a la minute cooking stations, can assist waste reduction by cooking meals according to guest orders.

- Replacing buffet service with the set menu during off and valley seasons. The set menu should be designed in co-operation with guests or tour leaders.

- Joining with charitable organizations (e.g., Egyptian food bank) to donate uneaten food or edible leftovers. To safeguard each participant from any potential liability, clear processes should be established.

- Effective implementation of the ‘4Rs’ (i.e., “reduce, reuse, recycle, and recover”). Several platforms (such as social media, television, and periodicals) should be utilized to highlight the importance of the 4Rs in the all-inclusive context.

- Create detailed instructions for the crucial processes that lead to waste that can be avoided. This relies on frequent inventory and stock control, FIFO, and a reduction in the size of plates and cups.

- Attention to FLW caused by hotel employees from the procurement stage until the post-service stage:

- A.

- Proper hiring processes and selection of educated and skilled employees.

- B.

- Conducting effective induction and training for reduction practices.

- C.

- During the high season, short training courses, or simulations and online courses, are required to engage part-time employees.

- D.

- Motivate hotel staff to apply the reduction strategy with the reward system. Hotel management can develop a concept of a ‘saver of the day’ between employees to reward them with a special bonus.

- E.

- Organize a “green team” of employees to promote environmentally friendly business practices in the workplace.

- F.

- Maintain constant communication within the team to guarantee policy compliance.

- G.

- Make signs to promote savings and current progress. Keep it brief and concentrate on the most important information, such as cost savings or environmental improvements.

- Emphasis on guest-related reasons for FLW (during post-service):

- A.

- Using different channels and methods to increase guest awareness and to help customers become more mindful of FLW. Channels such as social networks (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube), hotel websites, in-room information channels, booklets, mini table cards, signs, posters, and banners in restaurants and outlets, should be used to raise FLW awareness amongst guests.

- B.

- Co-operation with travel agencies and tour operators to engage and notify guests about the extent of FLW and what changes they might make to their behaviors to cut down on waste.

- C.

- Hotels can use a “heroes of the week concept,” in which a draw is held on a weekly basis to award free services to the family to one lucky guest who leaves no leftovers on their plate.

- D.

- Adding signs in the lobby area to show the extent of waste the previous day and how much food this could provide, to alter guests’ behavior toward FLW.

- Integration and adoption of technological innovations and applications to assist in the management, control, quantification and categorization of FLW.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacKenzie, N.; Gannon, M. Exploring the antecedents of sustainable tourism development. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2019, 31, 2411–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wells, V.K.; Taheri, B.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Manika, D. The role of generativity and attitudes on employees’ home and workplace water and energy saving behaviors. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zorpas, A.A.; Voukkali, I.; Pedreno, J.N. Tourist area metabolism and its potential to change through a proposed strategic plan in the framework of sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3609–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, S.I.; Arafat, H.A. Reduction of food waste generation in the hospitality industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, K.; Tonjes, D. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, T.; Bieg, C.; Harwatt, H.; Pudasaini, R.; Wellesley, L. Food System Impacts on Biodiversity Loss: Three Levers for Food System Transformation in Support of Nature; Chatham House Research Paper; Chatham House: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. FAO Is Closing the Food Loss and Waste Reduction Project with a Call for Sustained Efforts to Eradicate Hunger. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/egypt/news/detail-events/en/c/1203522/ (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Reuters. 2013. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-food-waste-idUSBRE9090TN20130110 (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- The Guardian. 2013. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment//jan/10/half-world-food-waste (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- FAO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IWP_2017_09.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- United Nations. 2017. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2017/TheSustainableDevelopmentGoalsReport2017.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Lins, M.; Puppin Zandonadi, R.; Raposo, A.; Ginani, V.C. Food Waste on Foodservice: An Overview through the Perspective of Sustainable Dimensions. Foods 2021, 10, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, I. University of Cape Coast Waste management practices of small hotels in Accra: An application of the waste management hierarchy model. J. Glob. Bus. Insights 2020, 5, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Taherib, B.; Giritlioglu, I.; Gannond, M. Tackling food waste in all-inclusive resort hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 28, 2483–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condratov, I. All-inclusive system adoption within Romanian tourist sector. Ecoforum. J. 2014, 3, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Moneim, A.; Gad, H.; Hassan, M. The Impact of All-Inclusive System on Hotels Profits: An Applied Study to Five-Star Hotels in Hurghada City. Int. J. Herit. Tour. Hosp. 2019, 13, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yolal, M.; Chi, Q.; Pesämaa, O. Examine destination loyalty of first-time and repeat visitors at all-inclusive resorts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1834–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almedia, M.M.; Robbin, C.F.; Pedroche, M.C.; Astorga, S. Revisiting green practices in the hotel industry: A comparison between mature and emerging destinations. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1415–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadban, S.; Shames, M.; Mayaleh, H.A. Trash crisis and solid waste management in Lebanon Analyzing hotels commitment and guests’ preferences. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 6, 1000169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdulredha, M.; Al Khaddar, R.; Jordan, D.; Kot, P.; Abdulridha, A.; Hashim, K. Estimating solid waste generation by hospitality industry during major festivals: A quantification model based on multiple regression. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.C.; Page, R.A. Marketing to the generations. J. Behav. Stud. Bus. 2011, 3, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, O.A.; Ilyasov, A. The food waste in five-star hotels: A study on Turkish guests’ attitudes. J. Tour Gastron. Stud. 2017, 5, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, B.; Cizel, B.; Cizel, R.B. Satisfaction with all-inclusive tourism resorts: The effects of satisfaction with destination and destination loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2012, 13, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Bilska, B.; Tul-Krzyszczuk, A.; Kołozyn-Krajewska, D. Estimation of the Scale of Food Waste in Hotel Food Services—A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, G.; Lugosi, P.; Hawkins, R. Food Waste Drivers in Corporate Luxury Hotels: Competing Perceptions and Priorities across the Service Cycle. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, W.; Turn, S.; Flachsbart, P. Characterization of food waste generators: A Hawaii case study. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2483–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; de Hooge, I.; Normann, A. Consumer-related food waste: Role of food marketing and retailers and potential for action. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2016, 28, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihoglu, G.; Salihoglu, N.K.; Ucaroglu, S.; Banar, M. Food loss and waste management in Turkey. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 248, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Program UNDP. Food Waste Index Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Boston Consulting Group (BCG). Tackling the 1.6-Billion-Ton Food Loss and Waste Crisis. 2018. Available online: www.bcg.com (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Egyptian Time Science. FAO Alerts of Increased Food Losses in Egypt and Arabian Region. 2012. Available online: http://egypttimesciences.blogspot.com (accessed on 15 June 2015).

- Reynolds, C.; Goucher, L.; Quested, T.; Bromley, S.; Gillick, S.; Wells, V.K.; Evans, D.; Koh, L.; Kanyama, A.C.; Katzeff, C.; et al. Review: Consumption-stage food waste reduction interventions—What works and how to design better interventions. Food Policy 2019, 83, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilt, K. Preventing Food Waste: Opportunities for Behavior Change and the Expansion of Food Recovery and Donation in Metro Vancouver. 2014. Available online: https://summit.sfu.ca/item/14104 (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Kantor, L.S.; Lipton, K.; Manchester, A.; Oliveira, V. Estimating and addressing America’s food losses. Food Rev. Int. 1997, 20, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, I. Innovation and 19th century hotel industry evolution. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Soto, E.; Armas-Gruz, Y.; Morini-Marrero, S.; Ramos-Henríquez, J.M. Hotel guests’ perceptions of environmental friendly practices in social media. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Coteau, D. Food waste management in hospitality operations: A critical review. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyngaard, A.T.; de Lange, R. The effectiveness of implementing eco initiatives to recycle water and food waste in selected Cape Town hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Gruen, B.; Dolnicar, S. Biting off more than they can chew: Food waste at hotel breakfast buffets. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, A.; Buchli, J.; Göbel, C.; Müller, C. Food waste in the Swiss food service industry Magnitude and potential for reduction. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- California Environmental Protection Agency. Restaurant Guide to Waste Reduction and Recycling Food for Thought. California environmental Protection Agency, Integrated Waste Management Board. 2013. Available online: http://www.calrecycle.ca.gov/publications/Documents/BizWaste/44198016.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Fieschi, M.; Pretato, U. Role of compostable tableware in food service and waste management. A life cycle assessment study. Waste Manag. 2018, 73, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunders, D. Wasted: How America is Losing up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill. Nat. Resour. Def. Counc. 2012, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Adenso-Díaz, B.; Mena, C. Food industry waste management. Sustain. Food Process. 2013, 18, 435–462. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, J.; Foskett, D.; Graham, D.; Hollier, A. Food and Beverage Management; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marthinsen, J.; Sundt, P.; Kaysen, O.; Kirkevaag, K. Prevention of Food Waste in Restaurants, Hotels, Canteens and Catering; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenaghen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Waste Resource Action Program. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Estimates_%20in_the_UK_Jan17.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Kallbekken, S.; Sælen, H. Nudging’ hotel guests to reduce food waste as a win–win environmental measure. Econ. Lett. 2013, 119, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immanuel, M.; Hartopo, R.; Anantodjaya, S.P.D.; Saroso, T. Food waste management: 3R approach in selected family-owned restaurants. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 2, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, M.; Hawkins, R. Waste Counts: A Handbook for Accommodation Operators. 2007. Available online: http://www.business.brookes.ac.uk/research/groups/files/waste_counts_ebook.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Fullerton, D.; Kinnaman, T.C. Household responses to pricing garbage by the bag. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 971–984. [Google Scholar]

- Radwan, H.R.; Jones, E.; Minoli, D. Managing solid waste in small hotels. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 18, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.; Taleb, M.A. Benchmarking waste disposal in the Egyptian hotel industry. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wan, T.H.; Hsu, Y.S.; Wong, J.Y.; Liu, S.H. Sustainable international tourist hotels: The role of the executive chef. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2017, 29, 1873–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Olya, H.; Ali, F.; Gannon, M.J. Understanding the influence of airport services cape on traveler dissatisfaction and misbehavior. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 1008–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, V.K.; Manika, D.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Taheri, B.; McCowlen, C. Heritage tourism, CSR and the role of employee environmental behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellis, E.; Lee, J.; Reeder, J.; Yip, C. Overcoming the Barriers to Zero Waste in Durham Restaurants; National Restaurant Association, Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornill, A. Formulating the research design. In Research Method for Business Students, 6th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2012; pp. 158–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Egyptian Hotel Association (EHA). 2021. Available online: http://www.egyptianhotels.org/Hotels.aspx?id=HURGHADA (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- TripAdvisor. 2021. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/Hotels-g297549.Hurghada_Red_SeaHotels.html (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/article/euromonitor-internationals-top-city-destinations-ranking1 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Krueger, R.; Casey, M. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobaih, A. Hospitality Employment Issues in Developing Countries: The Case of Egypt. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 14, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, B.; Özkul, E.; Candan, B. An Outlook on “all Inclusive” System as a Product Diversification Strategy in Terms of Consumer Attitudes. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rios, C.; Demen-Meier, C.; Gössling, S.; Cornuz, C. Food waste management innovations in the foodservice industry. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx-Pienaar, N.; Rand, G.D.; Fisher, H.; and Viljoen, A. The South African quick service restaurant industry and the wasteful company it keeps. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilibarda, N.; Food Safety and Food Waste in Hospitality. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Zero Hunger. 2019. Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-319-69626-3_107-1 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Medeiros, C.O.; Cavalli, S.B.; Salay, E. Food safety training in food services. In Practical Food Safety: Contemporary Issues and Future Directions, 1st ed.; Bhat, R., Gómez-López, V.M., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Wright, N.G.; Lozano, F.J.; Steinberger, J.K.; Padfield, R.; Ujang, Z. Conceptual framework for the study of food waste generation and prevention in the hospitality sector. Waste Manag. 2016, 49, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, L.; Pak, N.; and Potts, M.D. Tackling the issue of food waste in restaurants: Options for measurement method, reduction and behavioral change. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Bräutigam, K.R. Food waste prevention in Europe—A cause-driven approach to identify the most relevant leverage points for action. Resources, conservation, and recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne-Palacio, J.; Theis, M. Foodservice Management, 12th ed.; Pearson Education: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cavagnaro, E. The food and beverage department: At the heart of a sustainable hotel. In Guests on Earth: Sustainable Value Creation in Hospitality; Cavagnaro, E., Ed.; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 274–299. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, E.; Jie, F. To waste or not to waste: Exploring motivational factors of Generation Z hospitality employees towards food wastage in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P. European hoteliers’ environmental beliefs: Greening the business. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmann, C.; Göbel, C.; Friedrich, S.; Kreyenschmidt, J.; Ritter, G.; Teitscheid, P. A participatory approach to minimizing food waste in the food industry—A manual for managers. Sustainability 2017, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McAdams, B.; von Massow, M.; Gallant, M.; Hayhoe, M.A. A cross industry evaluation of food waste in restaurants. J. Food Serv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Taheri, B.; Gannon, M.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Hanifah, H. Does living in the vicinity of heritage tourism sites influence residents’ perceptions and attitudes? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1295–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I. Role of hotel management and catering technology institutes in ensuring food safety. In Food Safety in the 21st Century: Public Health Perspective, 1st ed.; Dudeja, P., Gupta, R.K., Minhas, A.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Rios, C.; Hofmann, A.; Mackenzie, N. Sustainability-oriented innovations in food waste management technology. Sustainability 2021, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Management operation | The availability of an effective reduction plan |

| Staff hiring process and training | |

| Awareness and motivation | |

| Characteristics of all-inclusive operation | |

| Impact of food safety in food waste | |

| Kitchen operation | |

| Food-service cycle | Menu Planning |

| Food Procurement | |

| Receiving and Storage | |

| Food Production | |

| Food Service | |

| All-inclusive employees | Staff behaviors |

| Staff awareness | |

| All-inclusive guests | Guest attitude |

| Guest awareness |

| Item | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 45 | 95.7 |

| Female | 2 | 4.3 | |

| Age | From 25–35 | 5 | 10.6 |

| From 36–45 | 22 | 46.8 | |

| From 46–60 | 20 | 42.6 | |

| Education Background | Bachelor’s degree | 32 | 68.1 |

| Postgraduate diploma | 3 | 6.4 | |

| Master’s degree | 7 | 14.9 | |

| PhD degree | 5 | 10.6 | |

| Type of hotel management | International corporate chain | 7 | 38.9 |

| National chain | 8 | 44.4 | |

| Independent | 3 | 16.7 | |

| Job Position | General manager | 8 | 17.0 |

| Food and beverage manager | 12 | 25.5 | |

| Quality assurance manager | 4 | 8.5 | |

| Training manager | 2 | 4.3 | |

| Executive chef | 8 | 17.0 | |

| Sous chef | 3 | 6.4 | |

| Restaurant manager | 7 | 14.9 | |

| Duty manager | 3 | 6.4 | |

| Hotel career experience | 1–5 years | 3 | 6.4 |

| 6–11 years | 13 | 27.6 | |

| 12–15 years | 14 | 29.8 | |

| More than 20 years | 17 | 36.2 | |

| Current hotel experience | 1–5 years | 7 | 14.9 |

| 6–11 years | 23 | 48.9 | |

| 12–15 years | 7 | 14.9 | |

| More than 15 years | 10 | 21.3 | |

| Stage | FLW Items | Reasons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Storage | Fish and seafood Meat and meat products Milk and dairy products Ice cream Butter | Improper storage temperature Improper storage equipment Over procurement Store-keeper does not follow standard stock control practices Expiration | |

| Vegetables and Fruit | Improper storage temperature and over procurement | ||

| Pasta and starchy food | Improper storage conditions | ||

| Food production | Fish and seafood Meat and meat products | Improper cooking because of unskilled staff Over-production due to bulk cooking | |

| Vegetables Fruit | Improper cutting and peeling because of improper machines, manual handling, and unskilled staff | ||

| Oil | Using one fryer for different cooking purposes, over-heating, and smoking. | ||

| During and post-service | Breakfast buffet | Bakery items | Surplus, excessive portions, quality of items below guest expectations. |

| Dairy products such as Yogurt Collection of cheeses | Yogurt is served by the bowl, not by portion creating guest surplus Unacceptable taste of imported cheese for domestic tourists Unacceptable taste of local cheese for foreign tourists | ||

| Salad, olives, and salad dressing | Generally wasted by international guests due to their different breakfast perceptions | ||

| Eggs | |||

| Hot and cold items | Guest plates surplus Below guest expectation | ||

| Fresh fruit | Leftovers, excessive portion size | ||

| During and post-service | Launch and dinner show Dinner show Buffet style | Rice and pasta | Overproduction and leftovers |

| International food items | Not required by domestic tourists | ||

| Local food items | Not required by international tourists | ||

| Soup | Over-production and type of soup may be below guest expectations | ||

| Sauce | Serving a variety of sauces and salad dressings that do not meet guest desires especially by domestic tourists | ||

| Dessert, Fresh fruit | Over-size portions and surplus, Unacceptable quality with a variety of items | ||

| Other service meal | A light meal such as mini pizza, burger, bakery items | Around the clock, there is food and beverage service, and guests may not be hungry but they pick up food to test as they have already pre-paid. | |

| Management | Include strategy for tackling FLW among the hotel strategies |

| The hiring process needs to be more rigorous, especially for food and beverage staff, and other skilled and educated staff required | |

| Regular training on reduction practices for relevant employees | |

| Monitoring staff behavior towards tackling FLW | |

| Increase the level of communication between departments and staff at all levels concerning proper food cycle | |

| Cascading awareness about the impact of FLW reduction among hotel employees | |

| Create the motivational drivers to encourage hotel employees to apply reduction strategy | |

| Sustain staff satisfaction by refining benefits to embrace the belief of “career” and decrease the turnover level | |

| Recognize the 4 Rs policy (reduce, reuse, recycle, and recover) | |

| Coordination/partnership with charitable organizations to donate unused food | |

| Using FLW for composting | |

| Separate the FLW into categories for environmental purposes | |

| Incorporate technological innovations in every aspect of the food service cycle with co-operation from technology providers | |

| F&B Team | Use some ingredients in multiple recipes and across multiple food service areas |

| Daily “dish of today” to use products that are close to expiry | |

| Have kids’ menus with suitable portions. For a buffet, have a kids’ corner with small dishes. | |

| Do not include a new dish without a test panel of staff and guests | |

| For storekeeper and kitchen staff, the proper use of quality control checks such as FIFO is mandatory | |

| Using technological equipment, applications, and programs to control procurement, storage, and cooking | |

| Avoid low-quality raw materials and food items | |

| Decrease bulk cooking to a minimum level | |

| Ensure the quality of cooked food through applying company standard recipes | |

| Serve set menus instead of buffet during the off and shoulder seasons | |

| Scale down large menus and plan menu items to suit the demands of most in-house guests whether international or local guests | |

| Frequently engineer menus to avoid the most wasteful items | |

| Serve food at the right temperature (hot to serve hot and cold to serve cold) | |

| Trimming and garnish to be at a minimum level, to ensure that dishes are entirely eaten | |

| Provide guests with accurate information about food items such as ingredients and taste | |

| Avoid buffet re-fill in the last quarter | |

| Using modern technology such as tablets over tables in restaurants to show food recipes and cooking steps for food items. Also, tablets can be used in awareness of the impact of FLW | |

| Guests | Involving hotel guests by encouraging them to behave sustainably and ethically |

| Provide guests with a small plate and a suitable portion | |

| Implement regular awareness campaigns using posters, toolkits, table cards, signs, and social media | |

| Educate and direct domestic guests about the flavor and taste of international food items | |

| Educat and direct international guests about the flavor and taste of local food items | |

| Frequently adopt buffet items matched with guests’ nationality, demographics, eating habits, and cultural backgrounds | |

| Offering doggy bags or food-boxes to clients to collect surplus food, ensuring food safety for doggy bags |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elnasr, A.E.A.; Aliane, N.; Agina, M.F. Tackling Food Waste in All-Inclusive Resort Hotels in Egypt. Processes 2021, 9, 2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9112056

Elnasr AEA, Aliane N, Agina MF. Tackling Food Waste in All-Inclusive Resort Hotels in Egypt. Processes. 2021; 9(11):2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9112056

Chicago/Turabian StyleElnasr, Ahmed E. Abu, Nadir Aliane, and Mohamed F. Agina. 2021. "Tackling Food Waste in All-Inclusive Resort Hotels in Egypt" Processes 9, no. 11: 2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9112056

APA StyleElnasr, A. E. A., Aliane, N., & Agina, M. F. (2021). Tackling Food Waste in All-Inclusive Resort Hotels in Egypt. Processes, 9(11), 2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9112056