The Role of Family in the Life Satisfaction of Young Adults: An Ecological-Systemic Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To describe the characteristics of life satisfaction according to types of parental family cohabitation.

- To explore the relationship between life satisfaction and personal (psychological distress) and social (social support) situations.

- To analyze how the social situation (perception of social support) affects the relationship between personal situation (psychological distress) and life satisfaction.

- To examine the moderating role of the family cohabitation model in the mediating influence of social situation (perception of social support) on the relationship between personal situation (psychological distress) and life satisfaction.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Information

2.2.2. Psychological Distress

2.2.3. Life Satisfaction

2.2.4. Social Support

2.2.5. Parental Family Cohabitation

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Correlational Analysis of the Instruments and Their Relationship with the Type of Parental Family Cohabitation

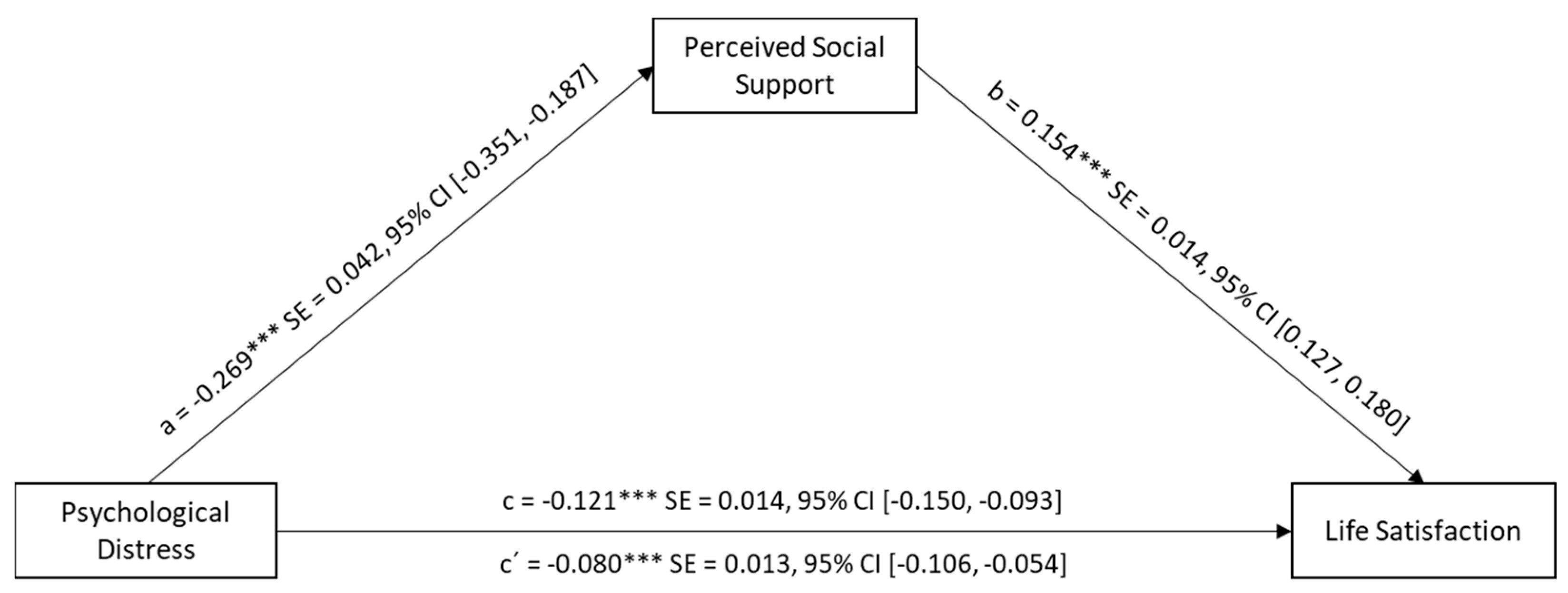

3.2. Social Support as a Mediator in the Relationship between Psychological Distress and Life Satisfaction

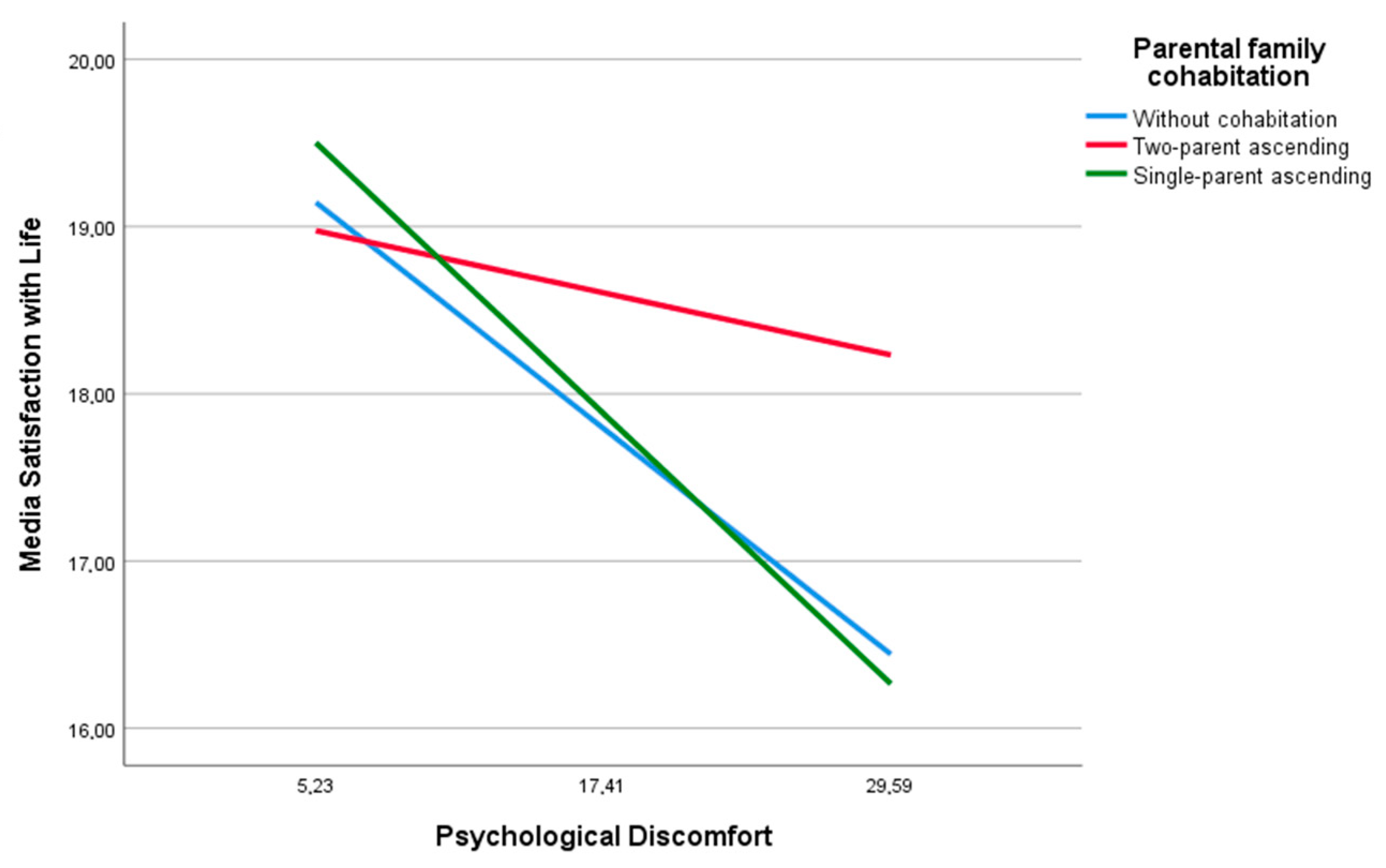

3.3. Parental Family Cohabitation as a Moderator in the Mediated Relationship of Perceived Social Support between Psychological Distress and Life Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Adolescent Health. World Health Organization. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Lowe, S.; Colleen, D.; Rhodes, J.E.; Zwiebach, L. Defining Adult Experiences: Perspectives of a Diverse Sample of Young Adults. J. Adolesc. Res. 2013, 28, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morshidi, M.I.; Toh, M.-H.C. Mental Health Among Young People. In Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1669–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.; Crapnell, T.; Lau, L.; Bennett, A.; Lotstein, D.; Ferris, M.; Kuo, A. Emerging Adulthood as a Critical Stage in the Life Course. In Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Halfon, N., Forrest, C., Lerner, R., Faustman, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Piko, B.F. Adolescent Life Satisfaction: Association with Psychological, School-Related, Religious and Socially Supportive Factors. Children 2023, 10, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmayr, R.; Wirthwein, L.; Modler, L.; Barry, M.M. Development of subjective well-being in adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belay, A.S.; Guangul, M.M.; Asmare, W.N.; Mesafint, G. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Psychological Distress among Nurses in Public Hospitals, Southwest, Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2021, 31, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carrión, R.; Villarejo-Carballido, B.; Villardón-Gallego, L. Children and adolescents mental health: A systematic review of interaction-based interventions in schools and communities. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granrud, M.D. Mental Health Problems among Homeless Adolescents: Public Health Nurses’ Work and Interprofessional Collaboration within the School Health Service. In Karlstad University Studies; Karlstad University: Karlstad, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative. Global Burden of Disease Study 2018 (GBD 2018) Results; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME): Seattle, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler, M.; Lane, R.I.; Wiley, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A.; Howard, M.E.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W. Follow-Up Survey of US Adult Reports of Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation during the COVID-19 Pandemic, September 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Subjective Well-Being: The Science of Happiness and Life. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 39, pp. 463–473. [Google Scholar]

- Antaramian, S. The Importance of Very High Life Satisfaction for Students’ Academic Success. Cogent Educ. 2017, 4, 1307622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Katz, C.C.; Fulginiti, A.; Taussig, H. Sources and Types of Social Supports and Their Association with Mental Health Symptoms and Life Satisfaction among Young Adults with a History of Out-of-Home Care. Children 2022, 9, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadyaya, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Developmental Dynamics between Young Adults’ Life Satisfaction and Engagement with Studies and Work. Longitud. Life Course Stud. 2017, 8, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Branquinho, C.; Moraes, B.; Cerqueira, A.; Tomé, G.; Noronha, C.; Gaspar, T.; Rodrigues, N.; Matos, M.G. Positive Youth Development, Mental Stress and Life Satisfaction in Middle School and High School Students in Portugal: Outcomes on Stress, Anxiety and Depression. Children 2024, 11, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, L.; Fernández, A.R.; Palacios, E.G. Adolescent Life Satisfaction Explained by Social Support, Emotion Regulation, and Resilience. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 694183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Martins, C.; Brás, M.; Carmo, C.; Gonçalves, A.; Pina, A. Impact of an Online Parenting Support Programme on Children’s Quality of Life. Children 2022, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Stevens, G.W.; Maes, M. Perceived Social Support from Different Sources and Adolescent Life Satisfaction Across 42 Countries/Regions: The Moderating Role of National-Level Generalized Trust. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 1384–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Martins, C.; Almeida, A.; Ayala-Nunes, L.; Gonçalves, A.; Nunes, C. The Adapted DUKE-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire in a Community Sample of Portuguese Parents. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2022, 32, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Stevens, M.; Purtscheller, D.; Knapp, M.; Fonagy, P.; Evans-Lacko, S. Mobilising Social Support to Improve Mental Health for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review Using Principles of Realist Synthesis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.S.; Saucier, D.A.; Hafner, E. Meta-Analysis of the Relationships between Social Support and Well-Being in Children and Adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 624–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariépy, G.; Honkaniemi, H.; Quesnel-Vallée, A. Social Support and Protection from Depression: Systematic Review of Current Findings in Western Countries. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, J.L.; Garside, R.B.; Labella, M.H.; Klimes-Dougan, B. Parent Socialization of Positive and Negative Emotions: Implications for Emotional Functioning, Life Satisfaction, and Distress. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 3455–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, M.J.; Marujo, H.A.; Charepe, Z.; Querido, A.; Laranjeira, C. Well-Being and Dispositional Hope in a Sample of Portuguese Citizens: The Mediating Role of Mental Health. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2101–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueger, S.Y.; Malecki, C.K.; Pyun, Y.; Aycock, C.; Coyle, S. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Association between Perceived Social Support and Depression in Childhood and Adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M. Distinctions between Social Support Concepts, Measures, and Models. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 413–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, B.C.; Collins, N.L. A New Look at Social Support: A Theoretical Perspective on Thriving through Relationships. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 19, 113–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecki, K.L.; Salthouse, T.A.; Oishi, S.; Jeswani, S. The Relationship between Social Support and Subjective Well-Being across Age. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 117, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, B.H.; Bergen, A.E. Social Support Concepts and Measures. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho Guedes, F.; Cerqueira, A.; Gaspar, S.; Gaspar, T.; Moreno, C.; Gaspar de Matos, M. Family Environment and Portuguese Adolescents: Impact on Quality of Life and Well-Being. Children 2022, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. The Association between Family Structure and Subjective Well-Being among Emerging Adults in China: Examining the Sequential Mediation Effects of Maternal Attachment, Peer Attachment, and Self-Efficacy. J. Adult Dev. 2019, 26, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, V.; Boyd, L.M.; Pragg, B. Parent–adolescent closeness, family belonging, and adolescent well-being across family structures. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2007–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Del Toro, J.; Scanlon, C.L.; Schall, J.D.; Zhang, A.L.; Belmont, A.M.; Plevniak, K.A. The Roles of Stress, Coping, and Parental Support in Adolescent Psychological Well-Being in the Context of COVID-19: A Daily-Diary Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, J. Ten Years of Marriage and Cohabitation Research in the Journal of Family and Economic Issues. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Khatiwada, J.; Muzembo, B.A.; Wada, K.; Ikeda, S. The Effect of Perceived Social Support on Psychological Distress and Life Satisfaction among Nepalese Migrants in Japan. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustamov, E.; Musayeva, T.; Xalilova, X.; Ismayilova, G.; Nahmatova, U. Investigating the Links between Social Support, Psychological Distress, and Life Satisfaction: A Mediation Analysis among Azerbaijani Adults. J. Posit. Psychol. Wellbeing 2023, 7, 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.L.; Manning, W.D.; Stykes, J.B. Family Structure and Child Well-Being: Integrating Family Complexity. J. Marriage Fam. 2015, 77, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassler, S.; Lichter, D.T. Cohabitation and Marriage: Complexity and Diversity in Union-Formation Patterns. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Axinn, W.G. Cohabitation Dissolution and Psychological Distress among Young Adults: The Role of Parenthood and Gender. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 102, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinisman, T.; Montserrat, C.; Casas, F. The Subjective Well-Being of Spanish Adolescents: Variations According to Different Living Arrangements. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 2374–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Comtois, K.; Bussières, E.L.; Cyr, C.; St-Onge, J.; Baudry, C.; Milot, T.; Labbé, A.P. Are Children and Adolescents in Foster Care at Greater Risk of Mental Health Problems than Their Counterparts? A Meta-Analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 127, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, I.; Brás, M.; Lemos, M.; Nunes, C. Psychological Distress Symptoms and Resilience Assets in Adolescents in Residential Care. Children 2021, 8, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seker, S.; Boonmann, C.; Gerger, H.; Jäggi, L.; d’Huart, D.; Schmeck, K.; Schmid, M. Mental Disorders among Adults Formerly in Out-of-Home Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1963–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.K.; Jaccard, J.; Ramey, S.L. The Relationship between Social Support and Life Satisfaction as a Function of Family Structure. J. Marriage Fam. 1996, 58, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkonen, J.; Bernardi, F.; Boertien, D. Family Dynamics and Child Outcomes: An Overview of Research and Open Questions. Eur. J. Popul. 2017, 33, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumariu, L.E.; Kerns, K.A. Parent-Child Attachment and Internalizing Symptoms in Childhood and Adolescence: A Review of Empirical Findings and Future Directions. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Baek, M.; Park, S. Association of Parent–Child Experiences with Insecure Attachment in Adulthood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2021, 13, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Nunes, L.; Nunes, C.; Lemos, I. Social Support and Parenting Stress in At-Risk Portuguese Families. J. Soc. Work 2017, 17, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E. Social Support: A Review. In The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology; Friedman, H.S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B.; Keppens, G. Gender Differences in Mental Health Problems among Adolescents and the Role of Social Support: Results from the Belgian Health Interview Surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecha, P.; Martin-Romero, N.; Sanchez-Lopez, A. Associations between Social Support Dimensions and Resilience Factors and Pathways of Influence in Depression and Anxiety Rates in Young Adults. Span. J. Psychol. 2023, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Mullan, J.T.; Semple, S.J.; Skaff, M.M. Caregiving and the Stress Process: An Overview of Concepts and Their Measures. Gerontologist 1990, 30, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed.; Husen, T., Postlethwaite, T.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1994; Volume 3, pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A. MedPower: An Interactive Tool for the Estimation of Power in Tests of Mediation [Computer Software]. 2017. Available online: https://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Paino, M.; Lemos-Giráldez, S.; Muñiz, J. Propiedades psicométricas de la Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) en universitarios españoles. Ansiedad Y Estrés 2010, 16, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atienza, F.; Pons, D.; Balaguer, I.; García-Merita, M. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la vida en adolescentes. Psicothema 2000, 12, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar]

- Landeta, O.; Calvete, E. Adaptación y validación de la Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido. Ansiedad Y Estrés 2002, 8, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Ed: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; LEA: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Musick, K.; Meier, A. Are Both Parents Always Better than One? Parental Conflict and Young Adult Well-Being. Soc. Sci. Res. 2010, 39, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Luo, J.; Boele, M.; Windhorst, D.; van Grieken, A.; Raat, H. Parent, Child, and Situational Factors Associated with Parenting Stress: A Systematic Review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 1687–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarik, A.S.; Conger, R.D. Stress and Child Development: A Review of the Family Stress Model. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Crossman, E.J.; Small, P.J. Resilience and Adversity. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Socioemotional Processes; Lamb, M.E., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 247–286. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, G.; de Sousa, B.; Crespo, C.; Relvas, A.P. Economic Strain and Quality of Life among Families with Emerging Adult Children: The Contributions of Family Rituals and Family Problem-Solving Communication. Fam. Process, 2023; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Leget, D.L.; LaCaille, L.J.; Hooker, S.A.; LaCaille, R.A.; Lauritsen, M.W. Applying Self-Determination Theory to Internalized Weight Stigma and Mental Health Correlates among Young and Middle Adult Women: A Structural Equation Model. J. Health Psychol. 2024, 13591053241248283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marum, G.; Clench-Aas, J.; Nes, R.B.; Raanaas, R.K. The Relationship between Negative Life Events, Psychological Distress and Life Satisfaction: A Population-Based Study. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, M.; Elias, P.; Ferreira Cunha, F.; Martins, C.; Nunes, C.; Carmo, C. Vulnerability to Suicide Ideation: Comparative Study between Adolescents with and without Psychosocial Risk. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappel, A.M.; Suldo, S.M.; Ogg, J.A. Associations between Adolescents’ Family Stressors and Life Satisfaction. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Maldonado, C.; Jiménez-Iglesias, A.; Camacho, I.; Rivera, F.; Moreno, C.; Matos, M.G. Factors Associated with Life Satisfaction of Adolescents Living with Employed and Unemployed Parents in Spain and Portugal: A Person-Focused Approach. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 110, 104740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Grunert, K.G.; Orellana, L.; Miranda, H.; Lobos, G.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Hueche, C. The Diverging Patterns of Life Satisfaction between Families: A Latent Profile Analysis in Dual-Earner Parents with Adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 7240–7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Young, T.; Samdal, O.; Torsheim, T.; Augustson, L.; Barkenow, V. Growing up Unequal: Gender and Socioeconomic Differences in Young People’s Health and Well-Being. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report from the 2013/2014 Survey; Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No. 7; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/303438/HSBC-No.7-Growing-up-unequal-Full-Report.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Kolisiati, A.; Vraka, I.; Kosiara, K.; Siskou, O.; Kaitelidou, D.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Gallos, P.; et al. Resilience and Social Support Improve Mental Health and Quality of Life in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Syndrome. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Categories | M (SD)/f (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 253 (49.2) |

| Woman | 261 (50.8) | |

| Age | 20.64 (2.30) | |

| 17–18 years | 122 (23.7) | |

| 19–21 years | 194 (37.7) | |

| 22–24 years | 198 (38.5) | |

| Educational and employment status | Study | 312 (60.7) |

| Work | 87 (16.9) | |

| Study and work | 103 (20) | |

| Neither studies nor works | 12 (2.3) | |

| Level of education | No education | 3 (0.6) |

| Primary education or basic general education | 7 (1.9) | |

| Compulsory secondary education or intermediate vocational training cycle | 63 (12.3) | |

| High school diploma or higher vocational training cycle | 195 (37.9) | |

| University studies | 246 (47.9) | |

| Parental family cohabitation | No parental family cohabitation | 143 (27.8) |

| Living in an ascending biparental family | 265 (51.6) | |

| Living in an ascending single-parent family | 106 (20.6) |

| No Parental Family Cohabitation (n = 143) | Living in an Ascending Biparental Family (n = 265) | Living in an Ascending Single-Parent Family (n = 106) | Total | r | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1 PD | 17.83 (11.95) | 16.50 (11.90) | 19.10 (13.05) | 17.41 (12.18) | - | - | - |

| 2 PSS | 59.92 (11.44) | 59.23 (12.44) | 60.09 (11.34) | 59.60 (11.93) | −0.27 *** | - | - |

| 3 LS | 17.78 (4.33) | 18.57 (4.08) | 17.74 (4.40) | 18.18 (4.22) | −0.35 *** | 0.50 *** | - |

| Consequents | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedents | M (Perceived Social Support) | Y (Life Satisfaction) | ||||||||

| β | SE | t | p | 95% CI | Β | SE | t | p | 95% CI | |

| X | −0.27 | 0.040 | −6.46 | 0.00 | −0.35, −0.19 | −0.11 | 0.02 | −4.47 | 0.00 | −0.16, −0.06 |

| M | 0.16 | 0.01 | 11.70 | 0.00 | 0.13, 0.18 | |||||

| W1 | −0.59 | 0.64 | −0.91 | 0.36 | −1.85, 0.67 | |||||

| W2 | 0.47 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.56 | −1.11, 2.05 | |||||

| X × W1 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 2.63 | 0.01 | 0.02, 0.14 | |||||

| X × W2 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.61 | 0.54 | −0.09, 0.05 | |||||

| Constant | 64.28 | 0.88 | 72.72 | 0.00 | 62.54, 66.02 | 10.29 | 1.02 | 10.12 | 0.00 | 8.29, 12.29 |

| Conditional effects | ||||||||||

| No parental family cohabitation | −0.11 | 0.02 | −4.47 | 0.00 | −0.16, −0.06 | |||||

| Living in an ascending biparental family | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.64 | 0.10 | −0.07, 0.01 | |||||

| Living in an ascending single-parent family | −0.13 | 0.03 | −5.05 | 0.00 | −0.18, −0.08 | |||||

| Δ2 (X × W) − R2 = 0.017, F (2507) = 0.017, p = 0.002 | ||||||||||

| R2 = 0.075 | R2 = 0.32 | |||||||||

| F (1512) = 41.720, p < 0.001 | F (6507) = 40.078, p < 0.001 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales Almeida, P.; Brás, M.; Nunes, C.; Martins, C. The Role of Family in the Life Satisfaction of Young Adults: An Ecological-Systemic Perspective. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2772-2786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14100182

Morales Almeida P, Brás M, Nunes C, Martins C. The Role of Family in the Life Satisfaction of Young Adults: An Ecological-Systemic Perspective. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2024; 14(10):2772-2786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14100182

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales Almeida, Paula, Marta Brás, Cristina Nunes, and Cátia Martins. 2024. "The Role of Family in the Life Satisfaction of Young Adults: An Ecological-Systemic Perspective" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 14, no. 10: 2772-2786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14100182

APA StyleMorales Almeida, P., Brás, M., Nunes, C., & Martins, C. (2024). The Role of Family in the Life Satisfaction of Young Adults: An Ecological-Systemic Perspective. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(10), 2772-2786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14100182