Abstract

Visible light communication (VLC) is an emerging optical wireless technology capable of delivering high data rates for both indoor and outdoor environments. When combined with multiple-input, multiple-output (MIMO) systems, VLC demonstrates enhanced capacity, extended transmission range, and improved reliability. However, VLC systems are susceptible to ambient light interference, which can degrade performance. This paper investigates the performance of MIMO-VLC systems using three modulation techniques: non-return to zero (NRZ), return to zero (RZ), and quadrature phase shift keying (QPSK). The study evaluates the VLC systems in terms of bit error rate (BER), quality factor (Q-factor), and received power over varying link distances. The obtained results show that MIMO-based systems outperform single-input, single-output (SISO) systems in terms of transmission range, with MIMO achieving up to 1450 m using QPSK, compared to 1125 m for SISO. Under ambient light noise, MIMO-based systems experience a greater reduction in transmission distance (13.6%) compared to SISO (6.2%), but the overall performance gain of MIMO compensates for this degradation. Among the modulation schemes, NRZ and QPSK provide the best performance, showing greater resilience to ambient light interference. The findings confirm that MIMO–VLC systems, particularly with NRZ and QPSK, offer a robust solution for overcoming interference and maximizing transmission distance in real-world applications.

1. Introduction

Optical communication, which uses light in transmission, offers increased data rates, longer transmission distances, and improved reliability. These factors made optical communication a solution for high-capacity, long-distance data transmission. Therefore, it emerged as a critical component of the internet backbone and data center infrastructure [1]. If the light used as a carrier signal falls in the visible light region, 400–700 nm or 430–750 THz of the electromagnetic spectrum, then such communication system is called visible light communication (VLC) [2,3,4,5]. It has several advantages such as supporting high data rates, using abundant free spectrum, and being immune to electromagnetic interference. Additionally, the implementation cost is lower. Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and light amplification by stimulated emission radiation (LASER) serve as transmitters, while photodiodes can be used as receivers. LEDs offer several advantages, including long lifespan, low manufacturing costs, and broad adoption in indoor lighting applications. In contrast, LASER provides a higher data rate and a longer range due to its higher frequency and power [6].

Visible light communication (VLC) has found applications in a wide range of areas such as light-fidelity (Li-Fi), intelligent transportation systems (ITS), vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communications, and smart city infrastructure [7,8,9,10,11]. These applications leverage VLC’s inherent advantages, including high data rates, enhanced security, and immunity to electromagnetic interference. Its use of visible spectrum light enables it to coexist with existing lighting infrastructure, making it a suitable candidate for various short- and medium-range wireless communication scenarios, particularly in indoor and controlled environments.

VLC has evolved beyond indoor environments to play a significant role in various outdoor applications, particularly in enhancing ITS [8]. VLC enables high-speed, secure, and interference-free communication, making it ideal for V2V and V2I communications [9,10]. These applications facilitate real-time data exchange for traffic management, collision avoidance, and autonomous vehicle coordination. Recent studies have highlighted VLC’s potential to improve traffic flow and safety by integrating it with traffic signals and vehicle headlights to create dynamic communication networks. Moreover, VLC’s low power consumption and immunity to electromagnetic interference make it ideal for energy-efficient, secure communication in rural or greenhouse environments, promoting sustainable farming practices.

In addition to transportation, VLC is being explored for applications in smart city infrastructure, where it can support data transmission for street lighting systems, public safety communications, and environmental monitoring [11,12]. By leveraging existing lighting infrastructure, VLC offers a cost-effective and energy-efficient solution for expanding communication networks in urban and rural areas.

Despite its advantages, VLC faces significant challenges such as limited range, susceptibility to blockages, and interference from sources like sunlight, daylight, LED lamps, and mobile phone screens. Ambient light is typically considered a DC-level signal under non-mobile conditions. Various techniques have been proposed to mitigate the impact of ambient light interference [13,14]. One common approach involves filtering the DC component by placing a capacitor at the receiver’s input, though this can introduce transmission delays. Another method uses a differential amplifier to subtract a positive DC voltage from the output of the transimpedance amplifier, or alternatively, summing a negative DC voltage with the output signal. Additionally, high-pass filters can be employed to eliminate low-frequency ambient light interference [15].

One approach to mitigating these issues is the use of multiple-input, multiple-output (MIMO) techniques, which transmit data in parallel from multiple sources [16,17,18,19]. MIMO, originally developed for wireless communication systems, addresses signal degradation caused by fading and other environmental impairments [20,21]. By employing spatial diversity using multiple spatially separated antennas for transmission and/or reception, MIMO enhances signal reliability and mitigates the effects of fading and interference, ultimately improving overall system performance. Furthermore, multiple users can be supported efficiently [22,23]. Therefore, spatial multiplexing can reduce the interference caused by ambient light.

Several alternative methods have been proposed for driving light sources (LEDs or LASER) in VLC systems. On-off keying (OOK) is one of the simplest modulation techniques used in VLC, but it requires detection threshold or logic level classification methods to estimate information bits for user mobility, which is a major drawback [17]. Additionally, the bit error rate (BER) performance of OOK is susceptible to interference from ambient light, as it causes fluctuations in the threshold level. This highlights the need for modulation schemes that can improve data bit detection without relying on a threshold. In this paper, we focus on non-return to zero (NRZ), return to zero (RZ), and quadrature phase shift keying (QPSK) to identify the most effective modulation schemes for improving the performance of MIMO–VLC systems [24,25,26].

In this paper, we study the performance of MIMO–VLC systems using various modulation techniques, with a focus on their transmission capabilities over different distances and resilience to ambient light interference. The spatial multiplexing inherent in MIMO systems helps reduce interference from ambient light, enabling MIMO to outperform SISO consistently in terms of distance coverage. Among the modulation schemes, NRZ and QPSK prove to be the most effective, demonstrating superior performance in mitigating ambient light interference. MIMO systems also exhibit greater robustness in challenging lighting conditions. The insights gained from this study provide valuable guidance for designing communication systems that meet specific performance requirements in diverse environments.

2. Related Work

Numerous research papers have been published in the literature focusing on VLC. A comprehensive survey of existing work on MIMO–VLC is conducted in [2], categorizing various MIMO techniques and providing brief descriptions of each, with a detailed discussion on the application of machine learning techniques in MIMO–VLC systems. The paper concludes by identifying future research directions for MIMO-based VLC systems. However, the study does not address the effects of ambient light interference, which is a critical factor for real-world implementations.

The work in [13] presents a framework to demonstrate the impact of ambient light on VLC systems. The results show that as ambient light levels increase, the BER performance deteriorates, ultimately saturating the receiver. While an experimental setup is employed to observe these effects, with a hybrid structure consisting of field programmable gate arrays (FPGA) and analog circuits used to amplify photodiode current and reduce ambient light interference, the study has notable limitations. It does not explore the use of MIMO technology. Additionally, it lacks an analysis of different modulation schemes that may further improve performance under varying ambient light conditions.

The article in [14] examines the effect of dynamic vehicular traffic density on the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and the corresponding BER performance of vehicle-to-vehicle VLC (V2V-VLC) systems. While the article provides insights into how traffic density affects communication performance, it does not consider the interference caused by ambient light, which is a significant factor in V2V–VLC systems. Additionally, the effects of using various modulation schemes on system performance under different traffic and lighting conditions are not explored.

The performance of the MIMO–VLC system in data transmission is assessed by considering factors like distance from the source, data bit rate, and modulation technique, in [16]. While the analysis provides valuable insights into system performance, it does not consider the impact of ambient light interference, a significant challenge in VLC systems. Moreover, the effects of different modulation schemes on system resilience to ambient light interference are not addressed, limiting the study’s applicability to real-world scenarios where such interference is common.

In [17], the performance of an indoor VLC system was studied using NRZ–OOK modulation, considering OptiSystem, showing improved performance compared to RZ–OOK modulation. However, this work is limited by its focus solely on NRZ–OOK and RZ–OOK without considering more advanced modulation techniques. Additionally, the study does not explore the use of MIMO systems, which are known to enhance system capacity and robustness significantly.

The study in [27] investigates the performance of an indoor VLC system using white LEDs modeled in OptiSystem. The system’s effectiveness is evaluated through measurements of the quality factor and BER at varying data rates and link lengths. With a Q factor of 6.508, the system achieves a transmission rate of 1 GB/s over a distance of up to 3 m. However, the investigation focuses solely on NRZ–OOK modulation, limiting its scope by not considering other modulation schemes that could improve performance. While the study examines VLC performance under external ambient light influences, it lacks a detailed analysis of ambient light interference beyond the use of a rectangular optical filter, leaving room for further exploration of more advanced interference mitigation techniques.

The study in [28] investigates multiple methods to suppress ambient light interference in the electronic, optical, communication, and wavelength domains, specifically focusing on VLC systems for vehicular communication. Designing transceivers for outdoor VLC systems is particularly challenging due to the dynamic nature of the environment and fluctuating interference from various ambient light sources.

Recent advancements have highlighted the potential of VLC in vehicular networks. Mouna Garai et al. [29] proposed a vehicular VLC network architecture facilitating wireless infrastructure-to-vehicle (I2V) and V2V communication. This architecture employs a tree-based network access scheme designed to maximize network coverage and enhance rapid connectivity beyond the reach of conventional lighting gateways. Furthermore, Dhouha Krichen et al. [30] explored the application of VLC in aeronautical networks for in-flight entertainment distribution. Their proposed architecture combines advanced wavelength assignment methods to mitigate intra- and inter-cell interference. Although the research provides valuable insights into optical interference across multiple physical domains, it lacks an in-depth exploration of the effects of modulation schemes and MIMO techniques.

The work by Han and Lee [31] introduces an ambient light noise filtering technique for MIMO–VLC systems, with a focus on mitigating the adverse effects of ambient light interference during high-speed multimedia data transmission. However, their study is limited to specific filtering configurations, leaving room for more extensive analyses, such as the inclusion of various modulation techniques and evaluation across different interference levels. In contrast, the present paper evaluates MIMO–VLC system performance using different modulation schemes (NRZ, RZ, and QPSK), offering a detailed quantitative analysis of BER, Q-factor, and received power under varying ambient noise conditions.

In [32], Jesuthasan et al. assess the performance of a MIMO–VLC system designed for data transmission, focusing on modulation schemes and signal processing techniques under typical communication conditions. However, their work does not explicitly consider the impact of ambient light interference on the system’s performance. Conversely, the current study provides a comprehensive evaluation of ambient light interference’s effect on MIMO–VLC systems, specifically addressing the performance of various modulation schemes (NRZ, RZ, QPSK) under significant ambient noise.

Finally, Sindhuja and Shankar [33] examine the use of MIMO technology in VLC systems for high-data-rate indoor wireless communication. Their research evaluates different types of LEDs (phosphor-converted, organic, micro-LED, RGB, and white LEDs) and analyzes their performance in terms of luminous flux, luminous efficacy, switching time, data rate, and brightness. While this work focuses on the performance of different LED types in a MIMO-VLC system, it does not consider the influence of ambient light interference on system performance. In contrast, the present study specifically explores how ambient light interference affects the BER, Q-factor, and transmission range of MIMO–VLC systems. Additionally, the current research offers a comparative analysis of various modulation schemes under these interference conditions, which is not covered in [33].

Table 1 provides a summary of the related work, highlighting the key objectives, technologies used, performance metrics, and main limitations of each study.

Table 1.

Summary of related work.

From the above discussion, it is evident that some studies on VLC systems focus on mitigating ambient light interference without incorporating MIMO techniques, while others explore MIMO techniques without addressing the impact of different modulation schemes or ambient light interference. This highlights the significance of the present study, which examines the performance of MIMO–VLC systems using various modulation techniques and different ambient noise sources. Our analysis specifically focuses on the systems’ ability to transmit over varying distances and their resilience to interference from ambient light, filling a critical gap in the existing research. The main contributions of this research are outlined as follows.

- Performance Evaluation of MIMO–VLC: The paper evaluates the performance of a MIMO–VLC system under various modulation techniques, specifically NRZ, RZ, and QPSK.

- Comparison of modulation schemes for ambient light interference mitigation: The paper compares the effectiveness of different modulation schemes (NRZ, RZ, and QPSK) in mitigating ambient light interference and optimizing performance.

- Resilience to Ambient Light Interference: The study investigates how MIMO-–LC systems perform in the presence of ambient light interference, focusing on the system’s robustness.

- Distance and Transmission Capability: It analyzes the system’s ability to transmit over different distances and assesses the performance in terms of distance coverage.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 3 introduces the MIMO-VLC system model, encompassing both the MIMO–VLC channel model and the ambient light noise model. Section 4 discusses the implementation of MIMO–VLC using OptiSystem. Simulation results and discussions are presented in Section 5. Lastly, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines potential future research directions.

3. VLC System Model

Traditionally, VLC systems have relied on LEDs as the primary light source due to their energy efficiency, low cost, and widespread availability. However, recent advancements have demonstrated the potential of laser-based light sources to overcome key limitations of LED-based systems, particularly in achieving higher data rates and extended transmission distances [34,35].

Laser-based VLC systems offer several advantages over their LED counterparts. The collimated beam profile of lasers significantly reduces beam divergence, enabling long-range communication with minimal attenuation. Additionally, lasers exhibit higher modulation bandwidths compared to LEDs, making them suitable for high-speed data transmission. Recent studies have validated these advantages in practical implementations. For instance, Chen et al. achieved indoor data rates of up to 100 Gbps and outdoor point-to-point transmission speeds of 4.8 Gbps using laser-based light sources, highlighting the feasibility of laser technology for both indoor and outdoor VLC applications [34].

Furthermore, Hou et al. presented a mobile VLC system utilizing lasers, demonstrating the ability of such systems to support dynamic communication scenarios while maintaining high-performance metrics. This study emphasizes the versatility of lasers in addressing the challenges of real-world VLC environments, including mobility and ambient light interference [35]. By leveraging these advancements, the proposed system employs laser-based light sources to achieve superior performance in terms of transmission distance, data rate, and noise resilience [36].

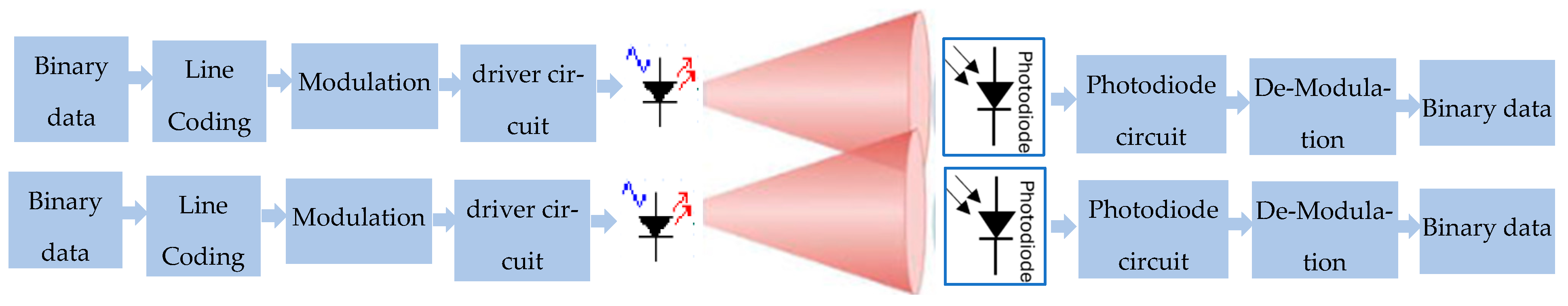

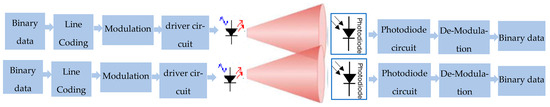

Figure 1 shows the block diagram of a 2 × 2 MIMO-based VLC system. According to this diagram, the data source generates binary data, which is passed through the line coding that uses NRZ or RZ techniques to convert binary data into electric pulses. Next, a certain type of modulation technique is used to modulate an electric pulse signal over a continuous wave light signal and produce a modulated light signal.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of a 2 × 2 MIMO-based VLC system.

Then the modulated signal is transmitted via LASER; the transmitted signal must be positive and real valued since LASER cannot send imaginary data [34,35,36,37]. At the receiver side, the light wave is detected through photodiodes, which are then demodulated, and the original binary data is recovered.

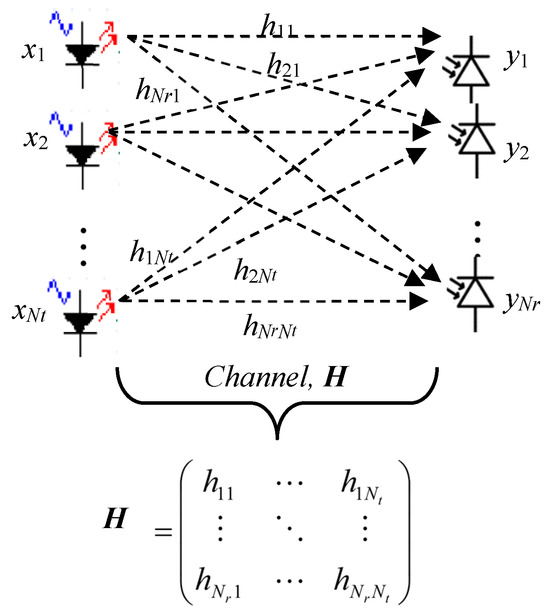

3.1. MIMO VLC Channel Model

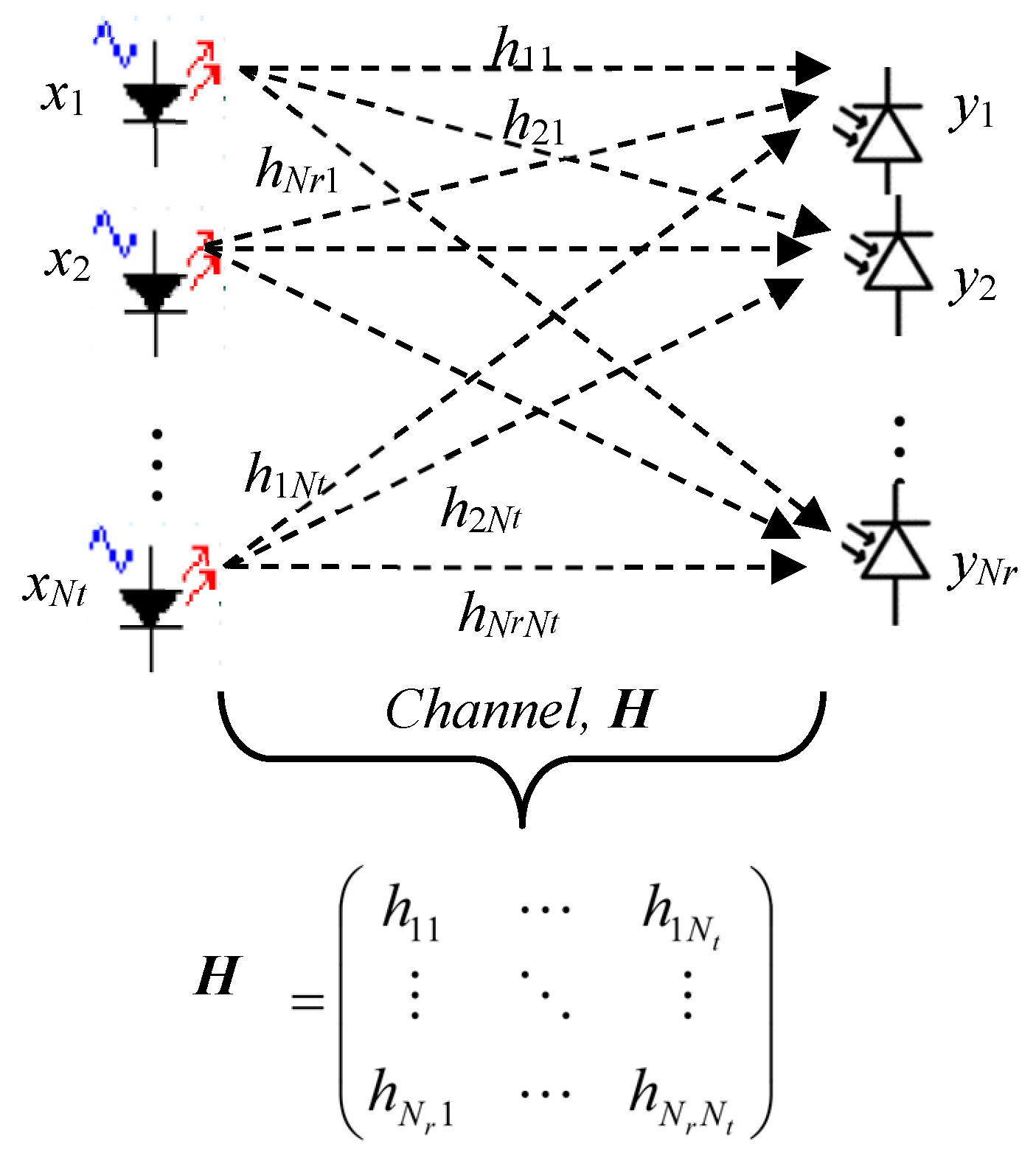

The presented system model is intended for outdoor, long-range, point-to-point communication scenarios. Figure 2 shows the MIMO–VLC channel model with LASER sources and photodiodes at the receiver. A DC bias is typically applied alongside the AC signal for each light source. This ensures that the transmitted data is positive and real valued. As a result, the input to each LASER consists of a combination of the DC bias and the AC signal.

Figure 2.

MIMO–VLC channel model with light sources and photodiodes.

Let be the transmitted signal vector, is the MIMO channel matrix gain. The received signal vector can be given by [2]:

where represents the noise vector, typically modeled as additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN), which is commonly used in analytical modeling of VLC systems. In this work, the noise is modeled as a combination of thermal noise and optical shot noise induced by ambient light sources, specifically fluorescent lamps and dimmable white LEDs, and is assumed to have zero mean with a variance given by [2]:

where are the thermal noise variance and shot noise variance, respectively. The shot noise is due to sunlight. Adaptive differential equalization, such as presented in [15,25], has been employed to mitigate the impact of optical interference and shot noise resulting from ambient light. In this work, we considered a deterministic channel model with a line-of-sight (LOS) component.

3.2. Ambient Light Noise Model

Ambient light refers to the natural or existing light in an environment, typically from sources like the sun or artificial lighting, such as fluorescent lamps and white LED [13,15]. It provides general, non-directional illumination that enhances overall visibility rather than focusing on a specific object or area. However, ambient light can lead to interference, signal attenuation, and reduced coverage range in VLC systems. The use of spatial multiplexing can help mitigate the interference caused by ambient light, as will be explained later.

Mathematical modeling of the ambient light noise generated by two different light sources (fluorescent lamp and white LED) is presented in this subsection. Let Ex(t) represent the light of white LED and Ef(t) and Ed(t) are the ambient lights of fluorescent lamp and white LED, respectively and written as [15]:

where n1(t) and n2(t) are the ambient interference noises from fluorescent lamps and white LED ambient light sources, respectively. f0, f1, and f2 represent the central optical frequencies within the spectral range of three distinct light sources, while , , and denote the respective elemental frequency intervals for each light source. Additionally, , , and correspond to random optical phases that are uncorrelated for each value of l. Finally, and Bi represents the spectral region of each light source.

At the receiver side, two types of shot noise are produced: stationary shot noise, which originates from the white LED and two ambient light sources biased by DC current, and non-stationary shot noise, which results from the time-varying photocurrent created by the NRZ-OOK signal and interference signals. The time-varying and non-stationary shot noise current can be modeled as [17].

where R is the responsivity of the photodetector, q represents the electronic charge, p(t) is the optical power at receiver, hi(t) represents the optical receiver impulse response, B is the noise bandwidth of the receiver, and finally τ is the integration variable representing time delay in the convolution operation between the received optical power and the squared impulse response of the optical receiver.

3.3. Modulation Characteristics and BER Performance

Each modulation scheme employed in this study possesses distinct characteristics that affect the performance of the VLC system. Additionally, the impact of ambient light interference varies across the modulation schemes due to their unique spectral attributes. This subsection highlights these characteristics and provides the BER expressions for the modulation schemes under consideration.

- NRZ: Its superior performance, particularly under ambient light interference, can be attributed to its lower spectral width and better energy efficiency, which reduce vulnerability to noise. The BER expression of NRZ is written as [16]:where Pr is the received optical power, N0 is the noise power spectral density and Q(.) is the Q-function and given as:

- RZ: While RZ modulation offers better timing accuracy, its higher bandwidth requirement and shorter pulse duration make it more susceptible to interference and attenuation, explaining its relatively lower performance. Its BER is expressed as [16]:

- QPSK: The robust phase-based modulation of QPSK provides enhanced resilience to noise and interference, which is why it performs well under challenging conditions. For QPSK, the BER is [27]:where N is the number of spatial streams in MIMO systems. The SNR in a MIMO system is calculated as:where Pt is the transmitted power vector. According to the above expressions, the BER in VLC systems depends on the received SNR, channel conditions, and the modulation scheme.

4. Implementation of MIMO–VLC Using OptiSystem

To evaluate the performance of the presented MIMO–VLC system, we utilize the optical system simulation software OptiSystem 21.0. As explained above, the main contribution of this study is to provide a comparative analysis of SISO–VLC and MIMO–VLC without and with the influence of ambient light with different line coding techniques.

4.1. Without Ambient Light

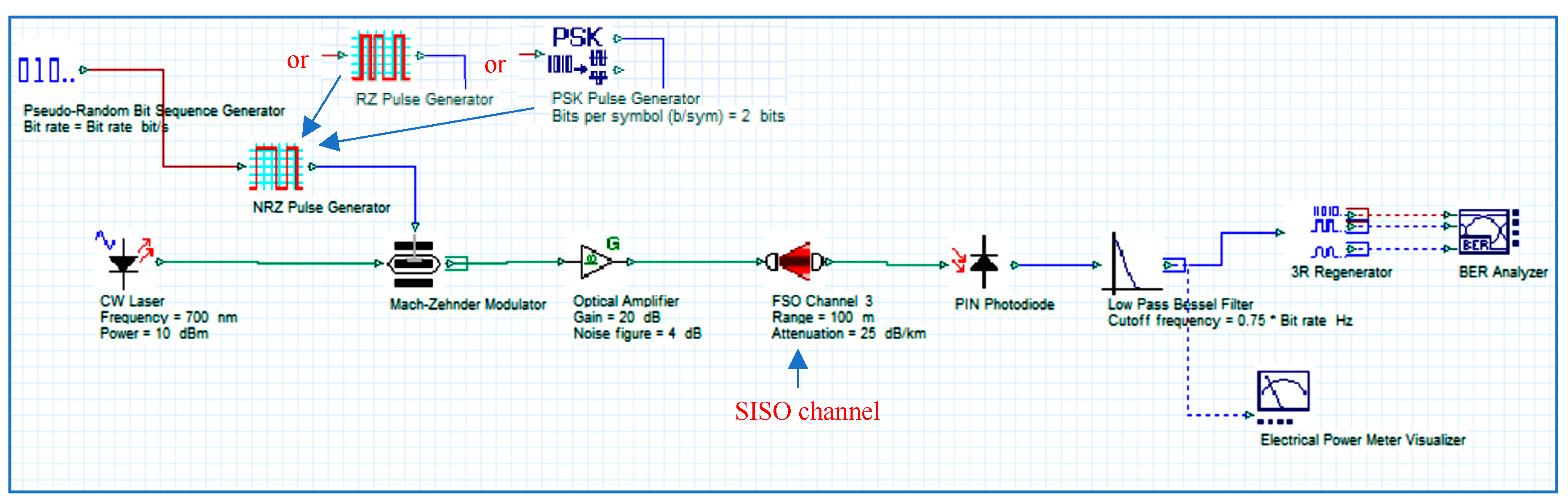

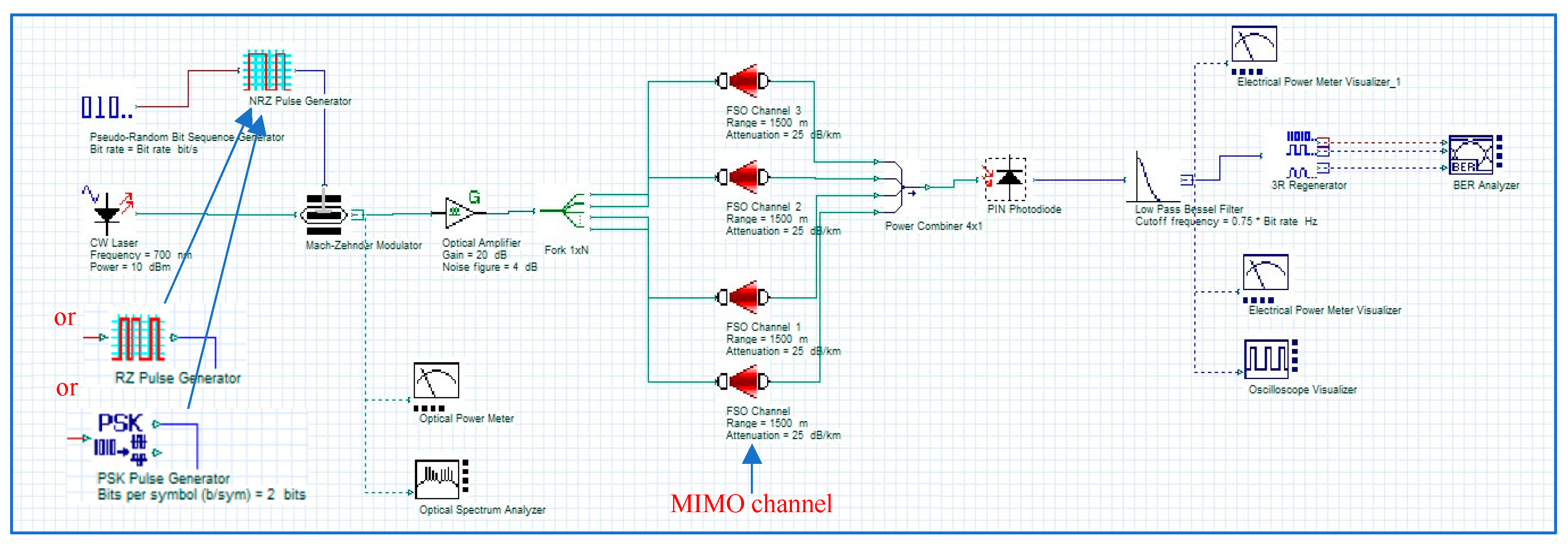

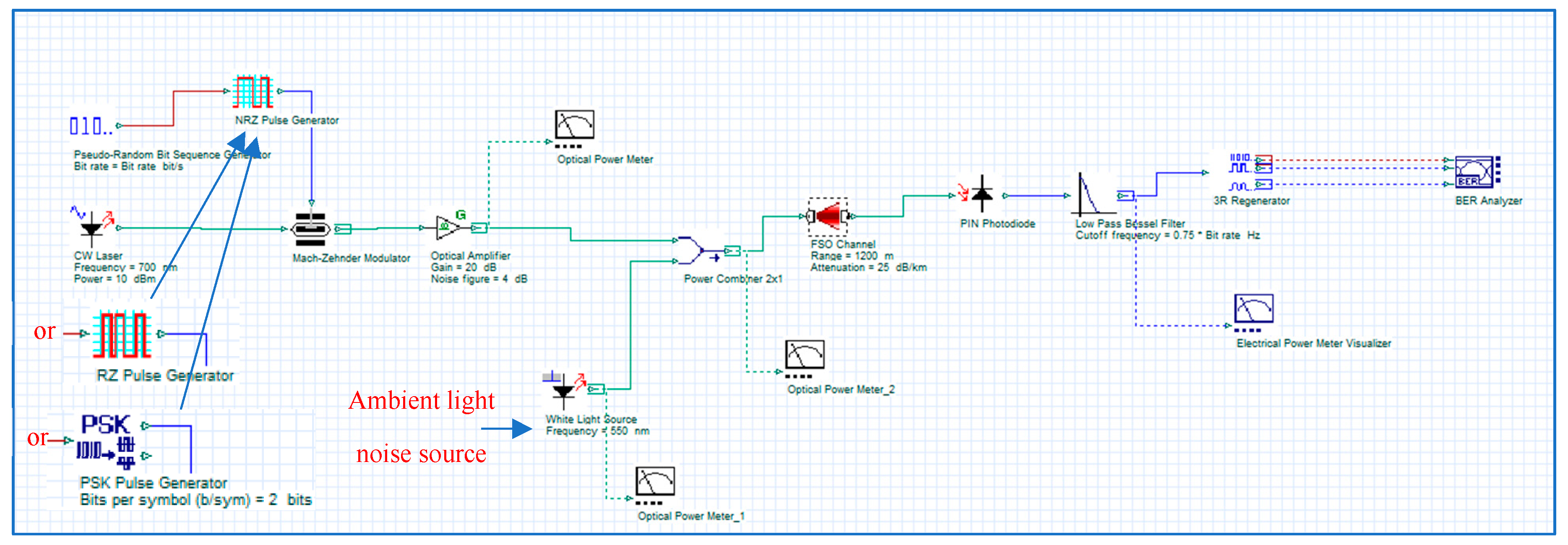

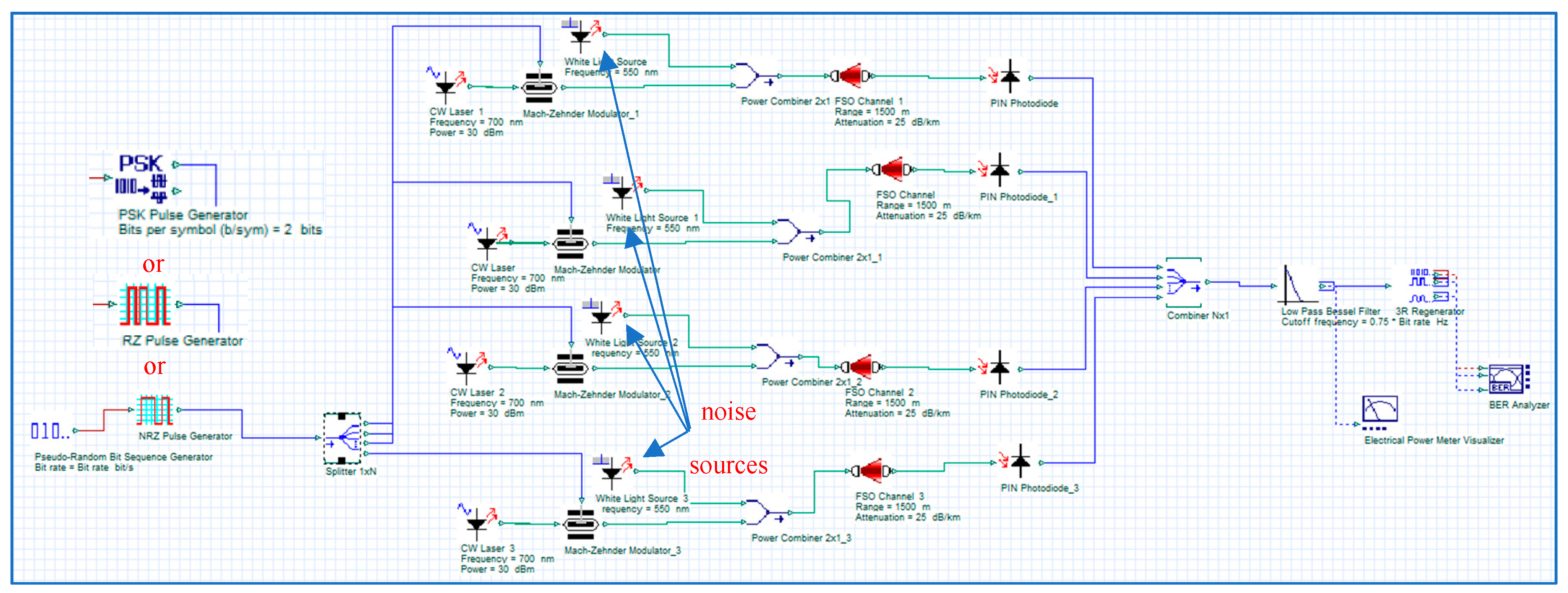

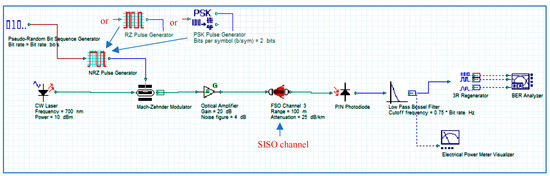

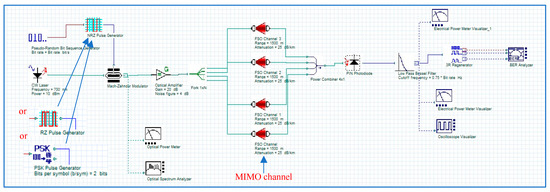

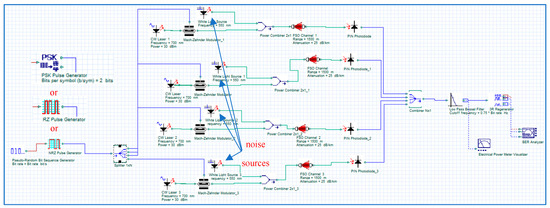

Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the implementation of SISO–VLC and MIMO–VLC systems, respectively, without considering the effects of ambient light noise. The implementation is done using three different types of line coding techniques: NRZ, RZ and PSK.

Figure 3.

SISO–VLC without ambient light with different line coding techniques.

Figure 4.

MIMO–VLC without ambient light with different line coding techniques.

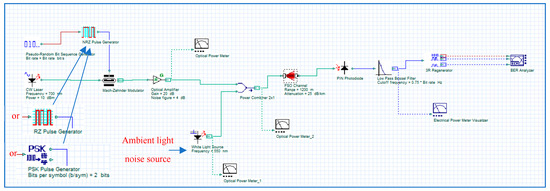

4.2. With Ambient Light

To illustrate the effects of ambient light noise sources on the performance of both SISO- and MIMO-based VLC systems, we implement the systems presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively. We considered two different light sources, which are the fluorescent lamp and white LED, with mathematical modeling presented in Section 3.2.

Figure 5.

SISO–VLC with ambient light noises and different line coding techniques.

Figure 6.

MIMO–VLC with ambient light noises and different line coding techniques.

5. Simulation Results and Discussions

To compare the performance of the considered systems, BER, received power and Q-factor are taken as metrics with the following parameters listed in Table 2. As indicated by the above figures, the transmitter side started by pseudo-random bit sequence generator with a rate 1 Gbps followed by a line coding technique (NRZ or RZ or PSK), then the modulator stage. We consider LASER as a light source with a wavelength of 700 nm and power 10 dBm. The data bits and laser light are received through a Mach–Zehnder (MZ) modulator. Two ambient light noise sources are considered with a wavelength of 550 nm. The channel may be SISO or MIMO according to the considered system. At the receiver side, the optical signal is recovered by PIN photodiode, which is then passed through a low-pass Bessel filter. A BER analyzer is utilized to calculate the BER.

Table 2.

Simulation parameters.

In Table 2, an attenuation value of 25 dB/km was chosen to represent a worst-case or highly lossy channel condition that may arise in realistic free-space optical (FSO) or long-range VLC scenarios, particularly under adverse environmental factors such as heavy ambient interference, fog, rain, or aerosol-dense atmospheres. This value allows the system’s performance to be evaluated under challenging outdoor conditions, ensuring that the proposed MIMO-VLC system is assessed in severe yet plausible attenuation scenarios.

5.1. Performance Analysis

BER and Q-factor are two metrics that indicate the quality of a communication link. BER is defined as the number of erroneous bits per total number of bits transmitted. Similarly, the Q-factor represents the difference between the average energy of correctly received bits and the average energy of incorrectly received bits, normalized by the standard deviation of the received signal. The relationship between the Q-factor and BER is inversely proportional: as the Q-factor increases, the BER decreases. Therefore, the Q-factor must be high, and the BER must be low.

5.2. Results Without Ambient Light Noise

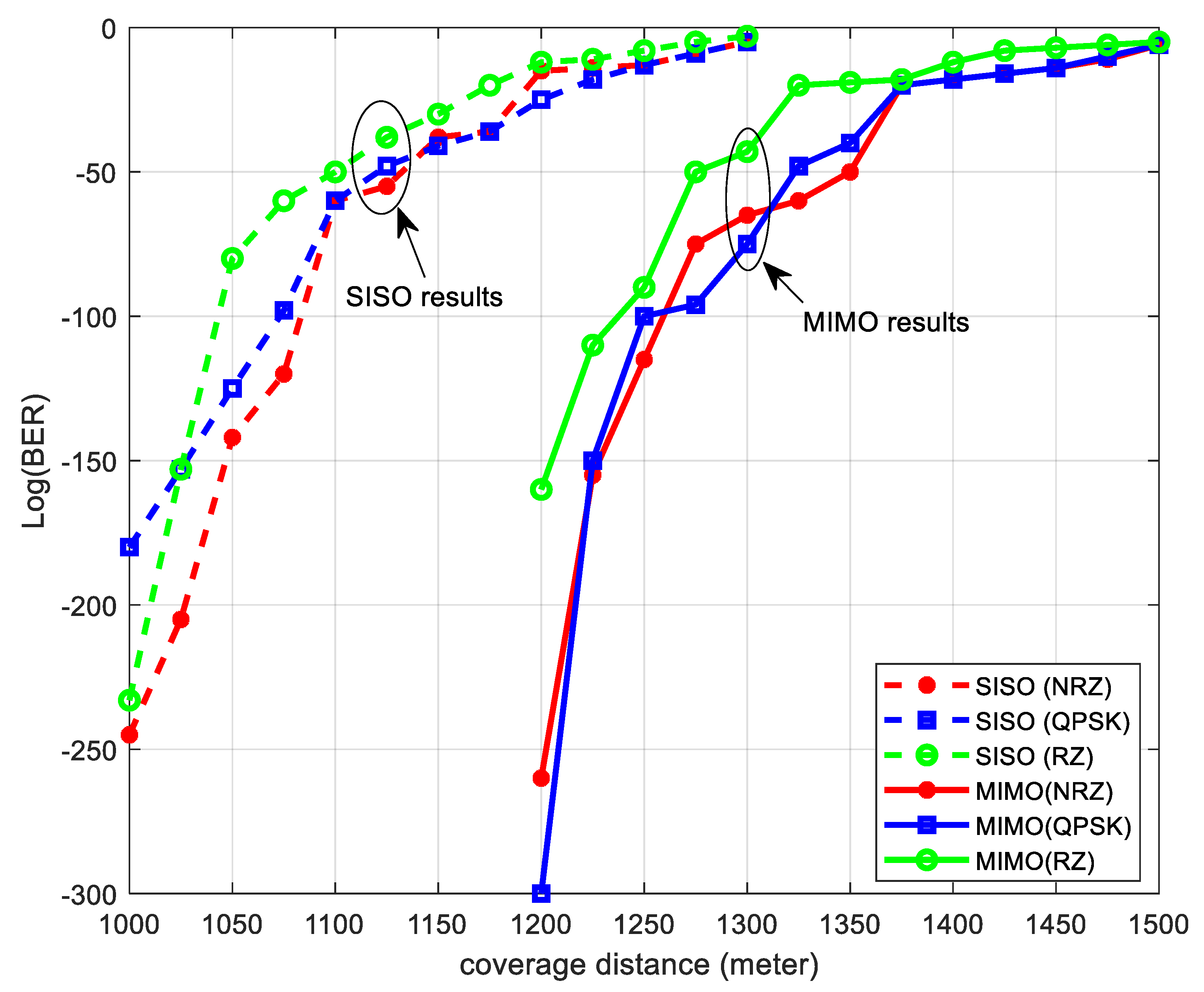

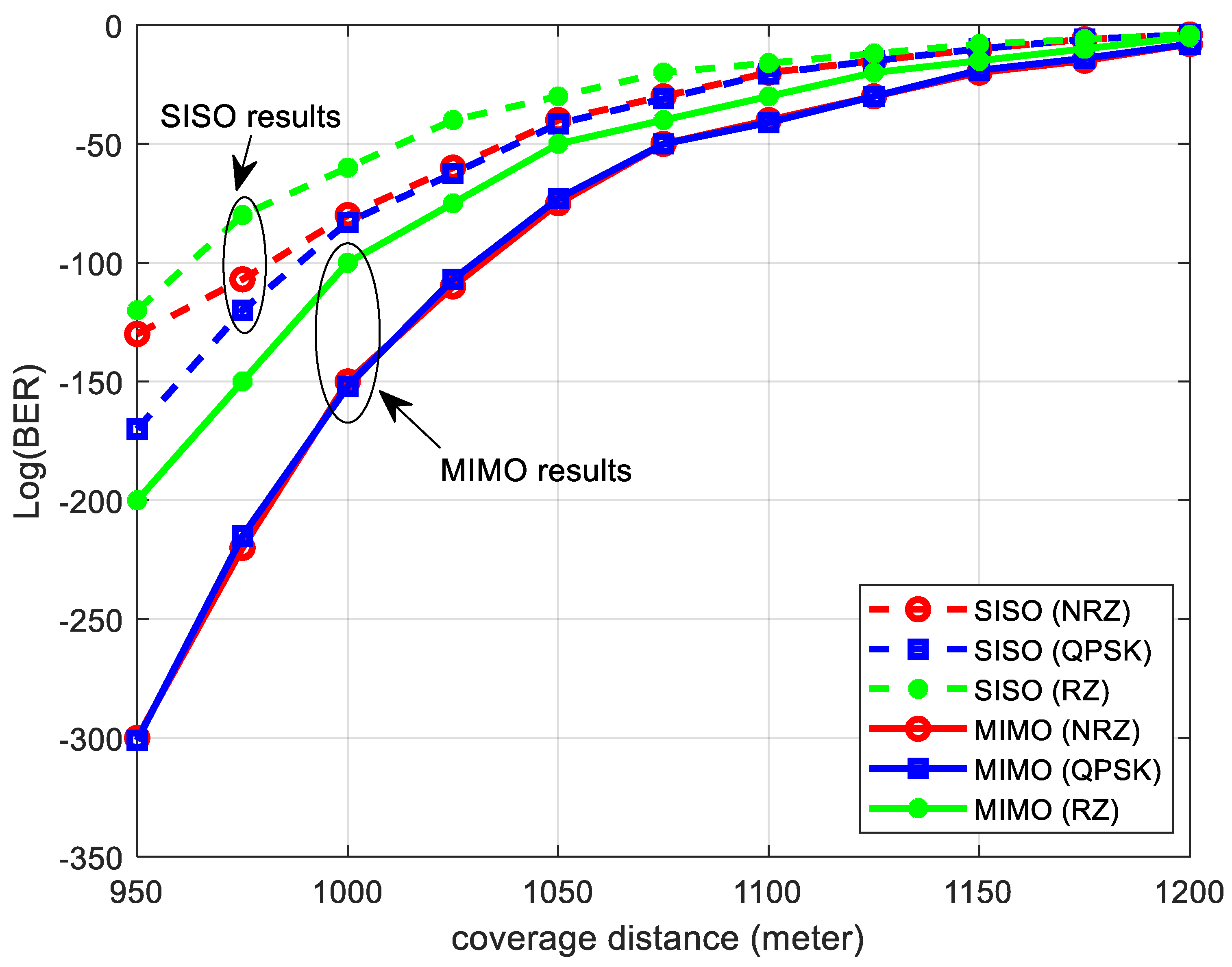

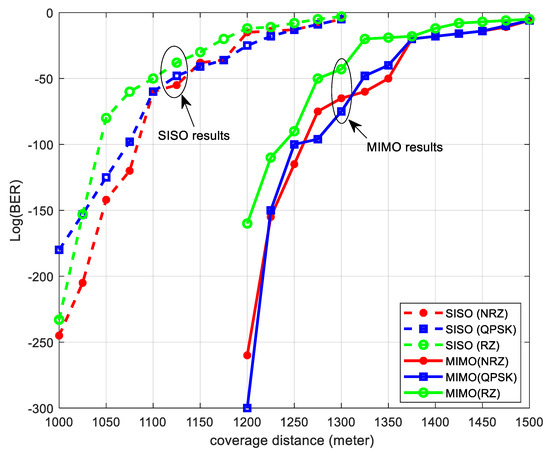

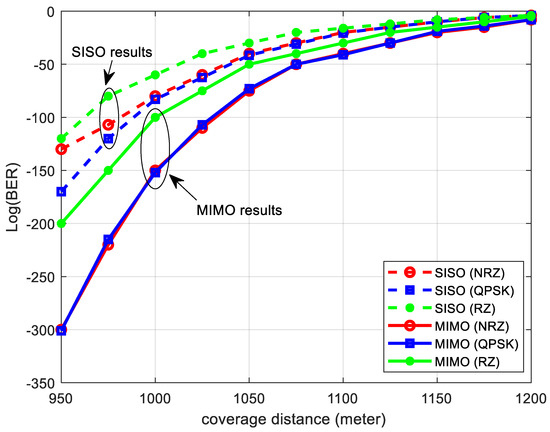

In this subsection, we evaluate the performance of the considered systems in terms of BER, Q-factor, and received power, excluding the effects of ambient light noise. Figure 7 presents the BER performance as a function of distance for both MIMO and SISO-based VLC systems. It is evident that both QPSK and NRZ techniques outperform the RZ technique in both SISO and MIMO systems. Furthermore, the MIMO-based VLC system outperforms the SISO–VLC system due to spatial multiplexing achieved by using multiple light sources and detectors.

Figure 7.

BER performance versus distance for both MIMO- and SISO-based VLC systems without considering ambient light noise.

Based on Figure 7, the RZ modulation briefly outperforms QPSK in terms of BER performance within the narrow distance range of 1000 to 1025 m. The temporary performance advantage of RZ modulation in this specific range is attributed to its better temporal signal separation, which reduces ISI at moderate transmission distances. In this region, the benefits of the shorter pulse duration in RZ help maintain clearer symbol distinction, especially under reduced noise influence, compared to QPSK, which, while spectrally efficient, is more sensitive to phase noise and ambient distortion under certain conditions. However, as the distance increases further, the higher spectral efficiency and robustness of QPSK allow it to outperform RZ in terms of BER and coverage, as stated above.

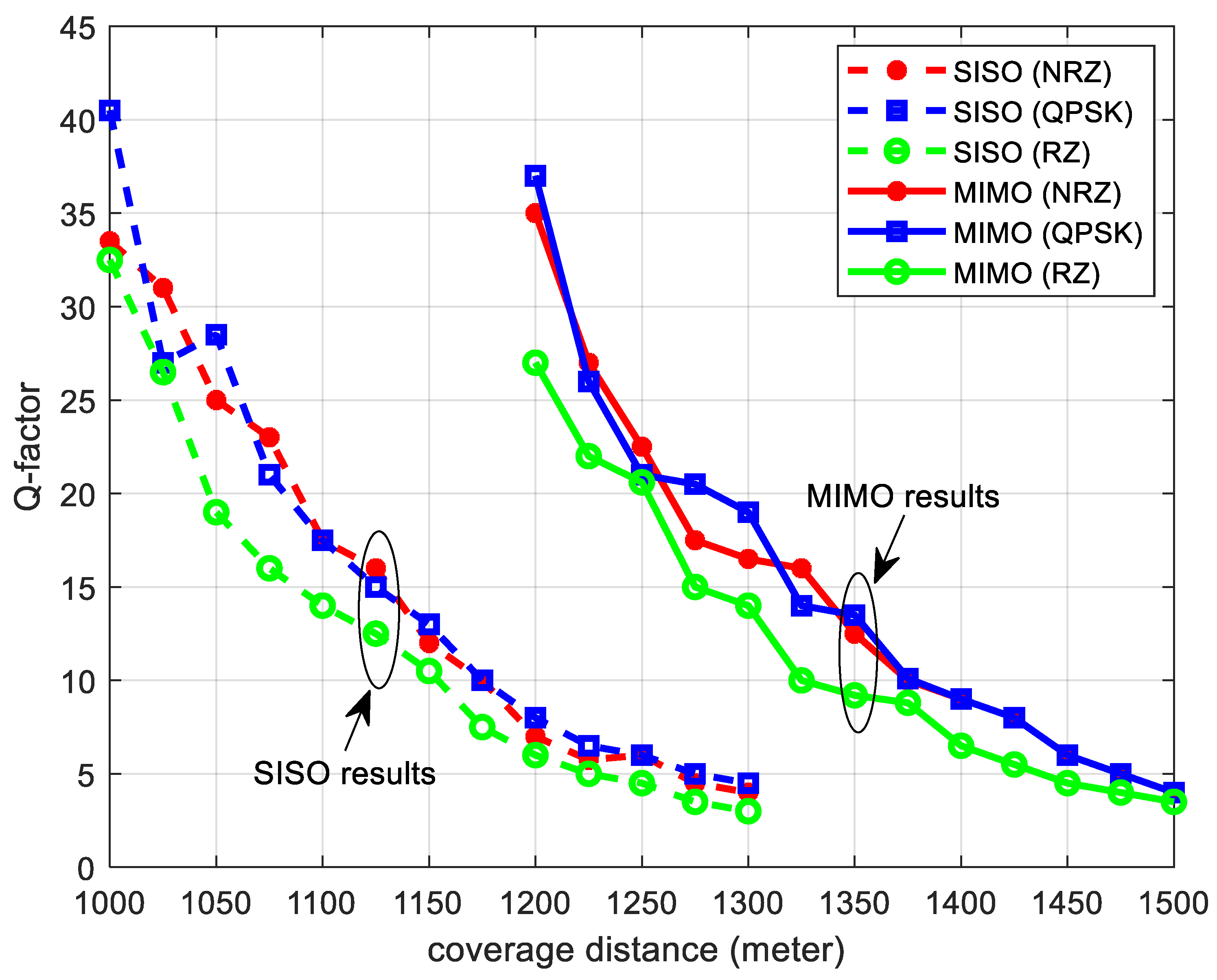

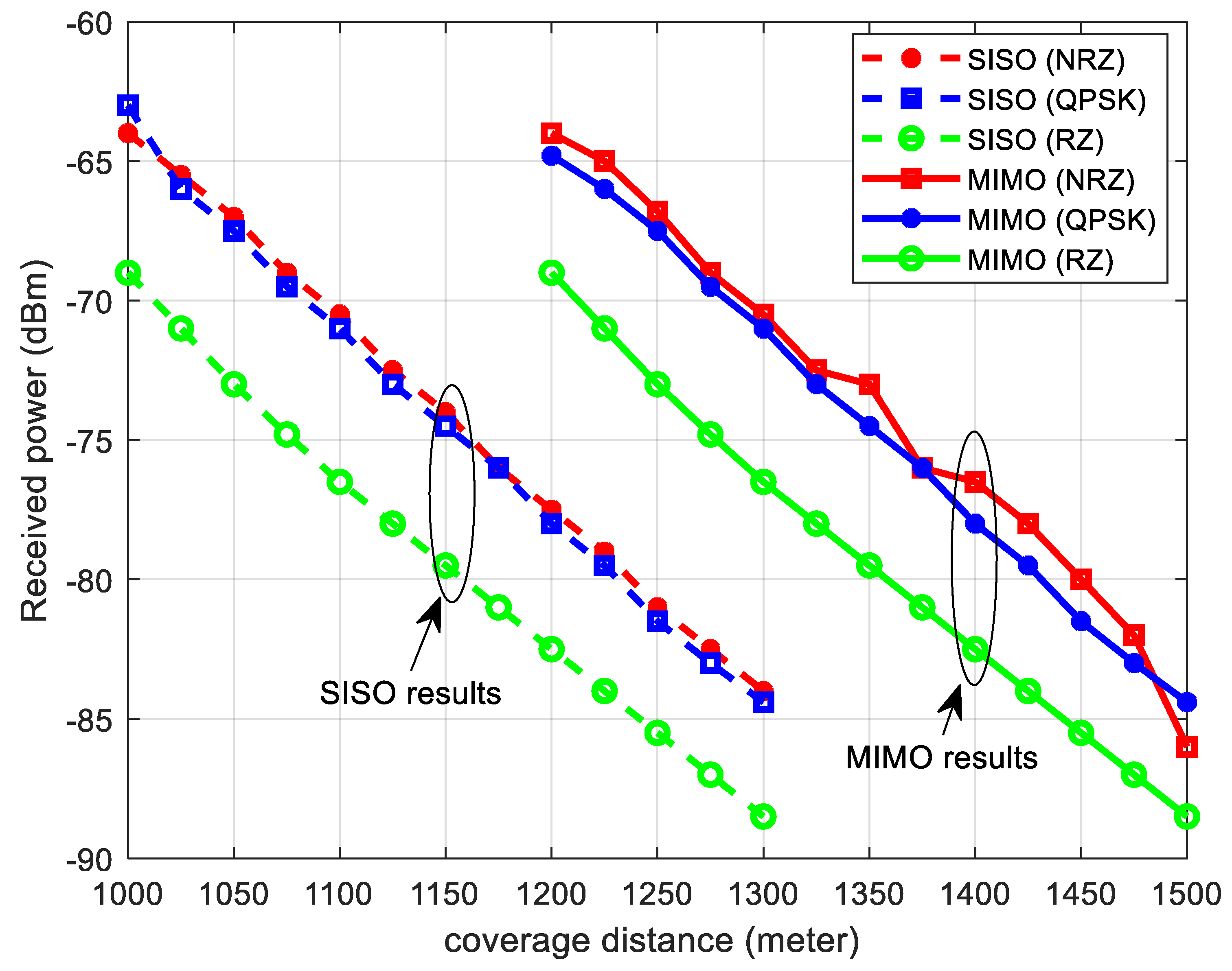

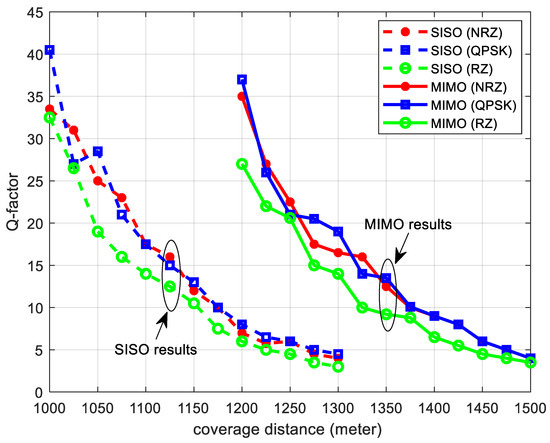

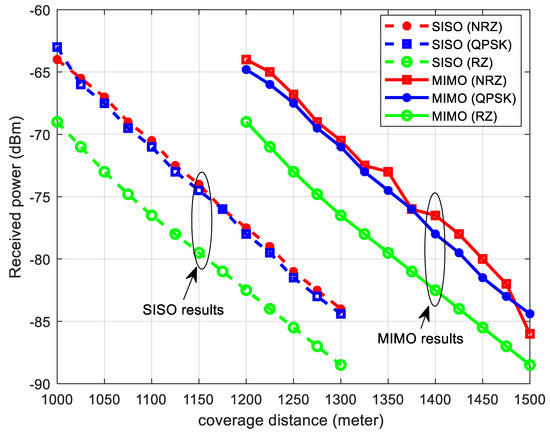

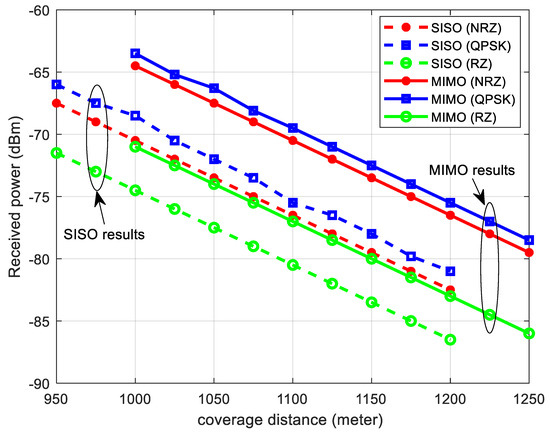

Figure 8 and Figure 9 depict the Q-factor and received power as a function of distance for both systems without considering ambient light noise, respectively, further supporting the observations from Figure 7. Table 3 presents the achievable link distance in both SISO and MIMO systems that achieve the acceptable BER limit, which must be greater than 1 per data rate.

Figure 8.

Q-factor as a function of distance for both MIMO- and SISO-based VLC systems without considering ambient light noise.

Figure 9.

Received power against distance for both MIMO- and SISO-based VLC systems without considering ambient light noise.

Table 3.

Achievable link distance excluding the effects of ambient light noise.

As demonstrated in Table 3, the MIMO system achieves greater transmission distances compared to the SISO system. The results show that MIMO systems, particularly with NRZ and QPSK modulation, achieve longer distances, while RZ performs the worst in both systems.

It is important to note that minor inconsistencies between Q-factor and BER results may occur, particularly near the performance degradation threshold. This is due to the nonlinear relationship between the Q-factor and BER, especially when modulation schemes are subjected to complex channel conditions, such as ISI. While the Q-factor provides a statistical measure of signal quality based on the separation between logic levels and noise margins, BER is a direct measure of bit errors over time. As a result, transient effects, such as variations in noise, phase distortions, or symbol misalignments, may cause short-range discrepancies between the two metrics (as in SISO scenario 1000 to 1025 m). These effects are more pronounced at the edge of the communication range, where signal degradation accelerates, and different modulation schemes respond differently to distortion. Such variations are expected and do not imply fundamental contradictions but rather reflect the sensitivity of each metric to different aspects of signal quality.

5.3. Results with Ambient Light Noise

In this subsection, we consider the effects of ambient light noise sources. As explained above, two ambient noise sources are considered, which are fluorescent lamps and white LEDs as presented in Section 3.2.

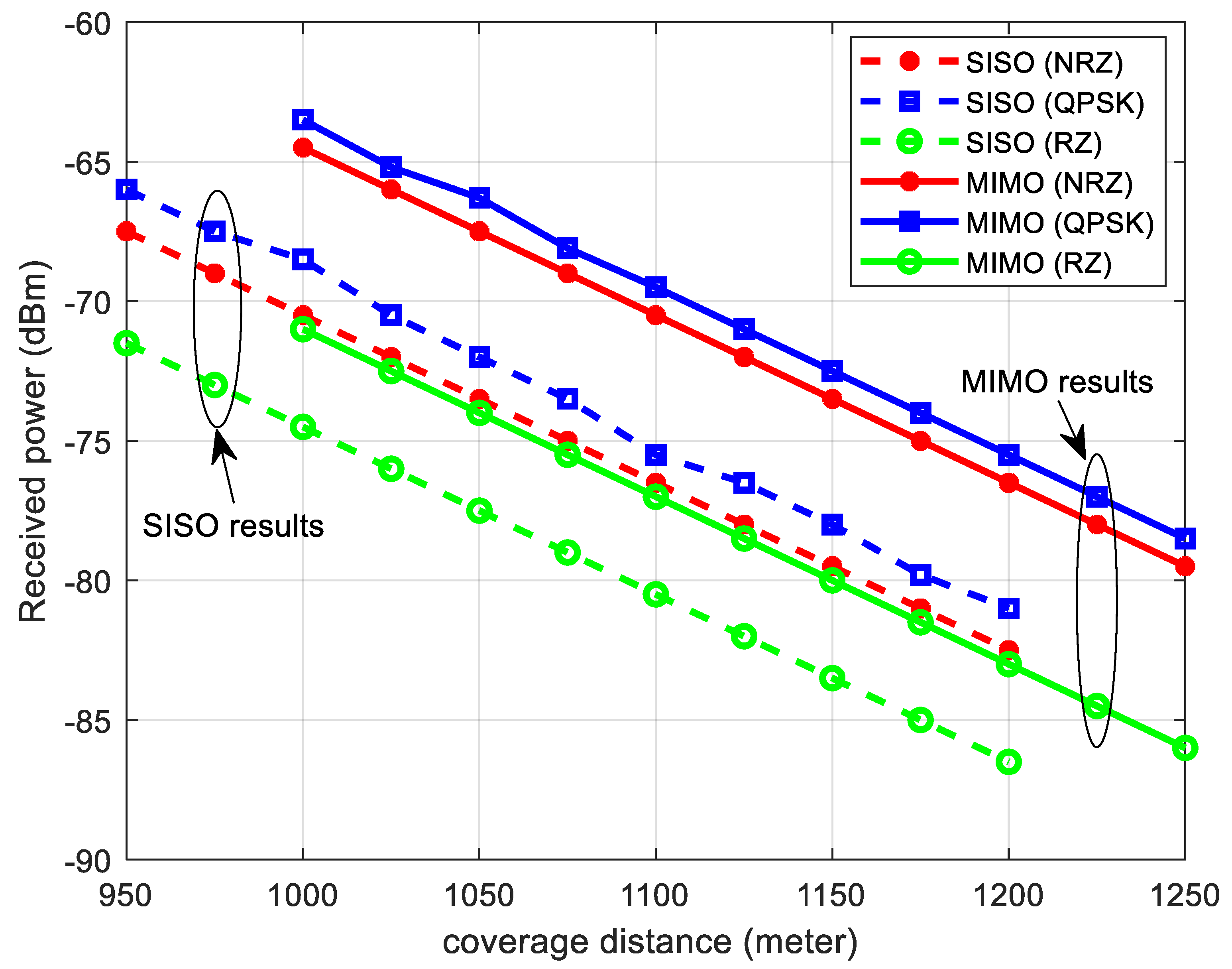

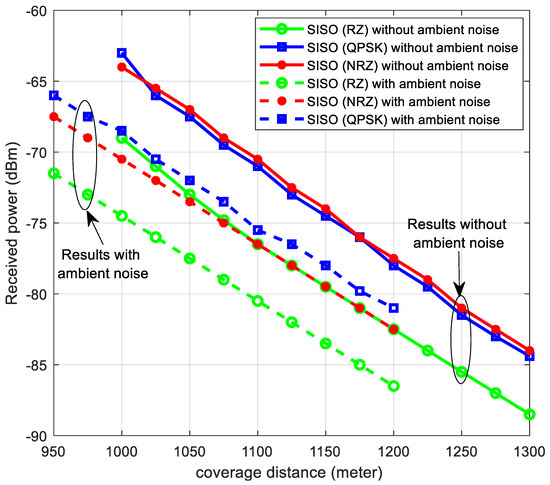

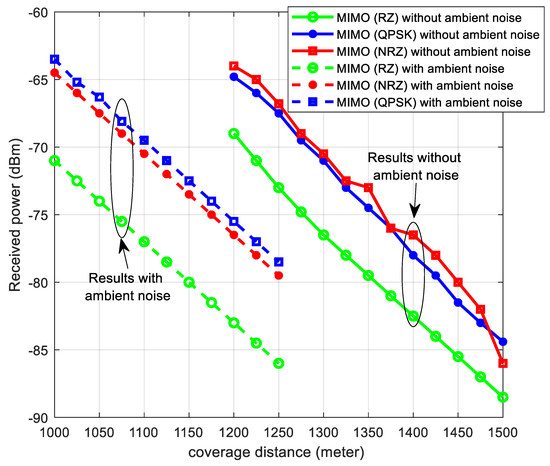

Figure 10 and Figure 11 present the BER and received power versus distance for both MIMO- and SISO-based VLC systems with ambient light noises. It is observed that MIMO enables more efficient transmission over longer distances, exhibiting better results in terms of received power and minimized BER even in the presence of ambient light noises. Also, the higher-order modulation technique, QPSK, demonstrates superior performance in MIMO–VLC systems. Table 4 presents the achievable link distance in both SISO and MIMO systems with ambient light noise.

Figure 10.

BER performance against distance for both MIMO- and SISO-based VLC systems with ambient light noise.

Figure 11.

Received power versus distance for both MIMO- and SISO-based VLC systems with ambient light noise.

Table 4.

Achievable link distance considering the effects of ambient light noise.

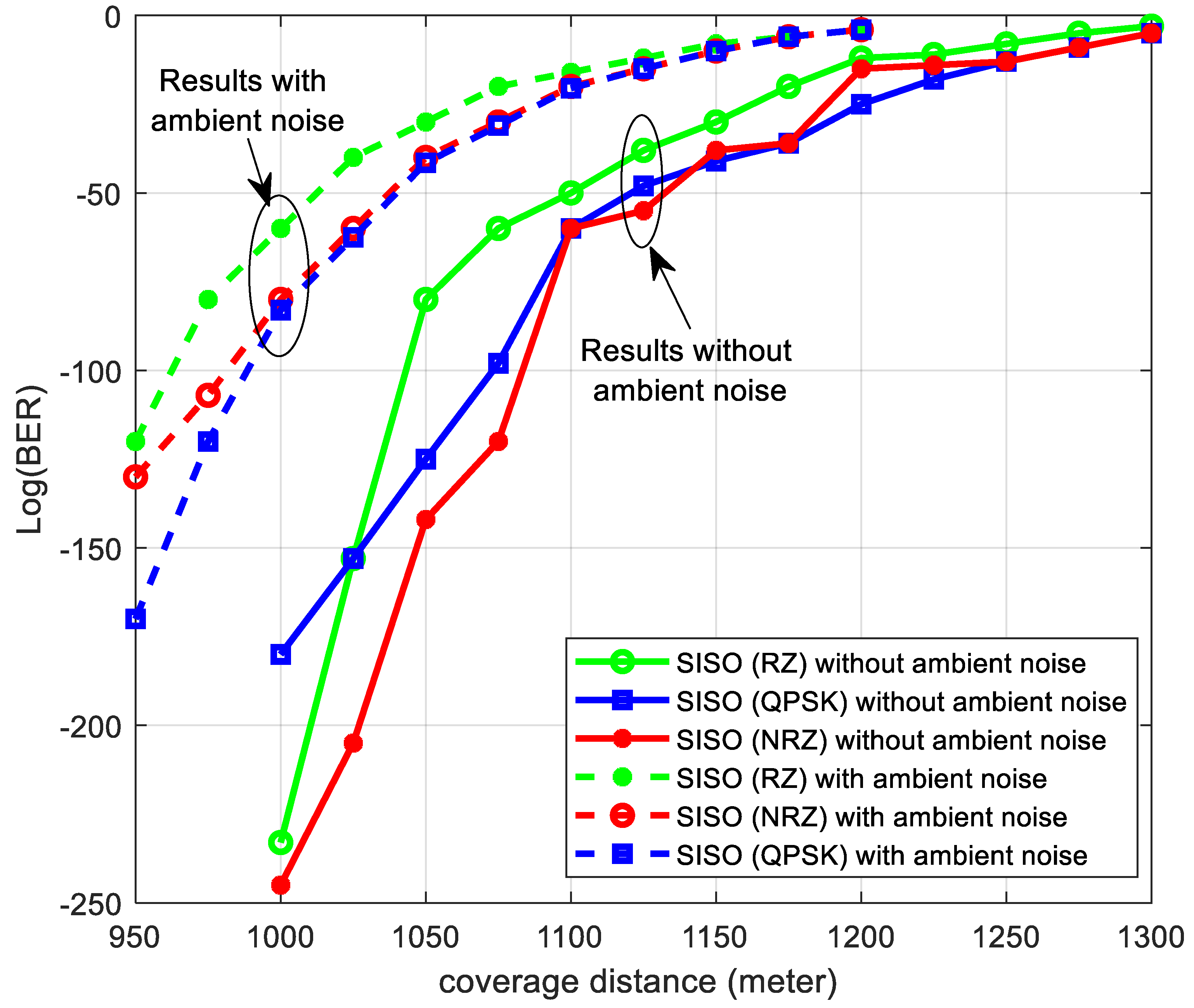

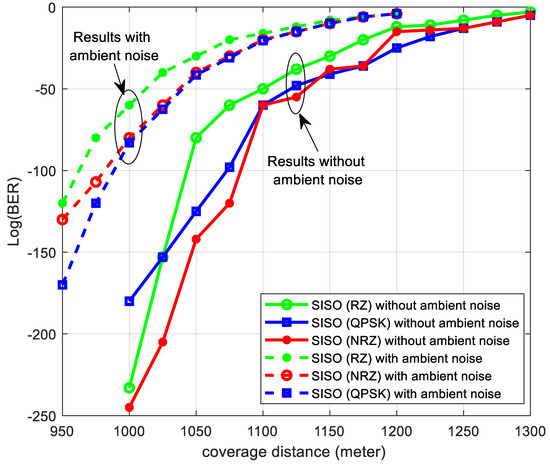

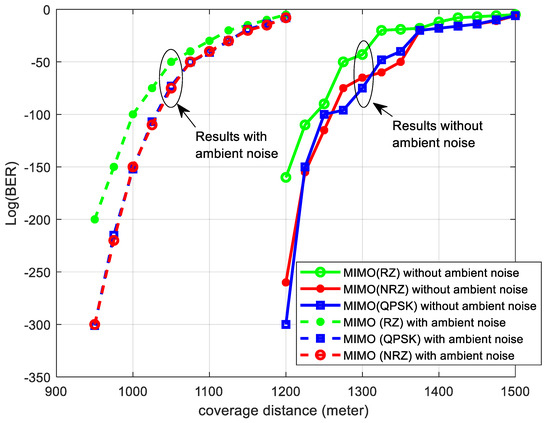

5.4. Performance Comparison

This subsection compares the performance of SISO and MIMO systems under scenarios with and without ambient noise. Figure 12 illustrates the detrimental effects of ambient light noise on the SISO–VLC system, showing a decrease in coverage distance from 1125 m to 1040 m (a 7.6% reduction) at a log(BER) of −50 dB, using the QPSK technique.

Figure 12.

BER performance comparison for the SISO–VLC system with and without ambient noises.

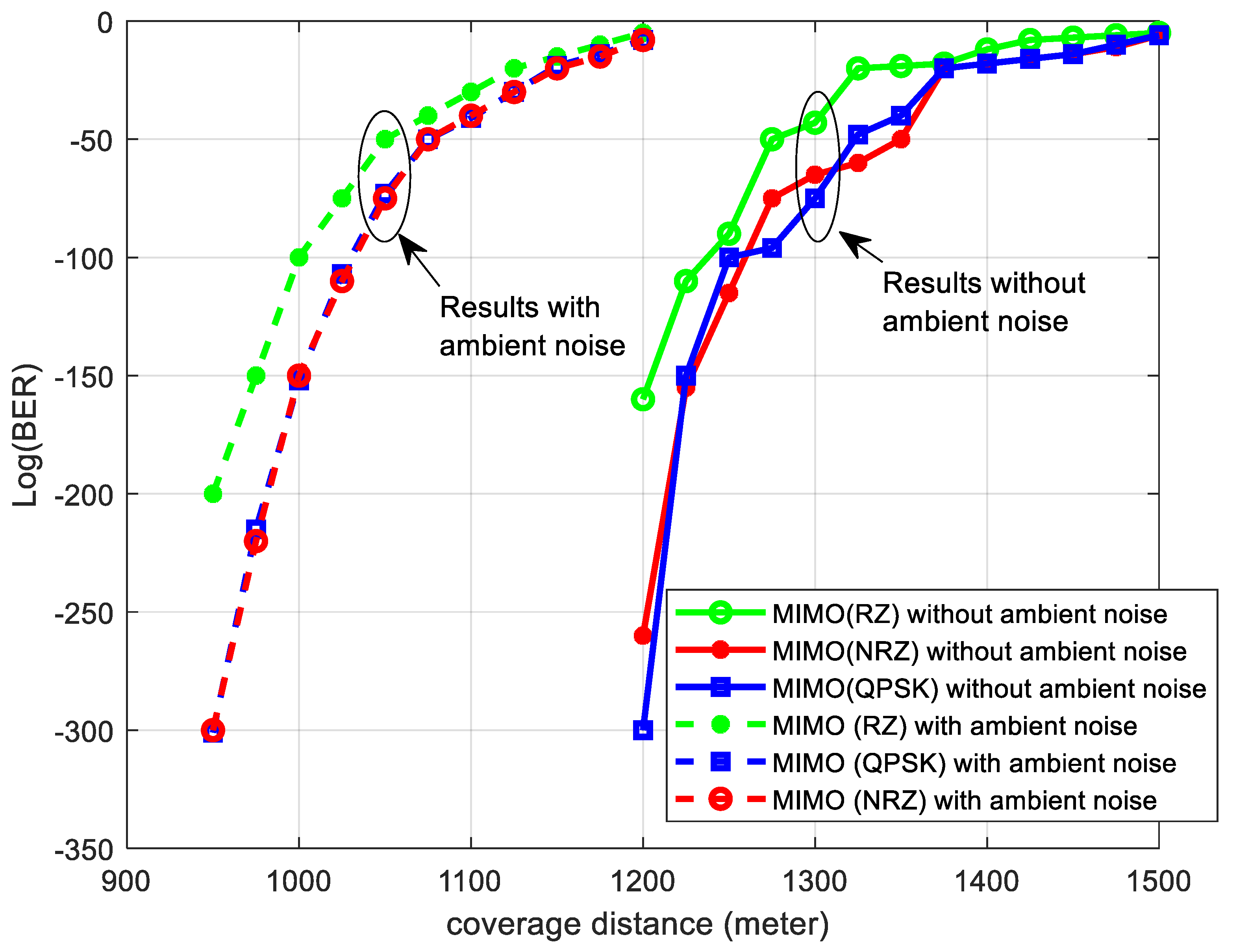

Similarly, Figure 13 displays the impact on the MIMO–VLC system, where at the same BER level, the coverage distance drops from 1325 m to 1075 m, marking an 18.9% reduction. Despite this, the overall performance gain provided by MIMO’s diversity outweighs the losses caused by ambient noise.

Figure 13.

BER performance comparison for the MIMO–VLC system with and without ambient noises.

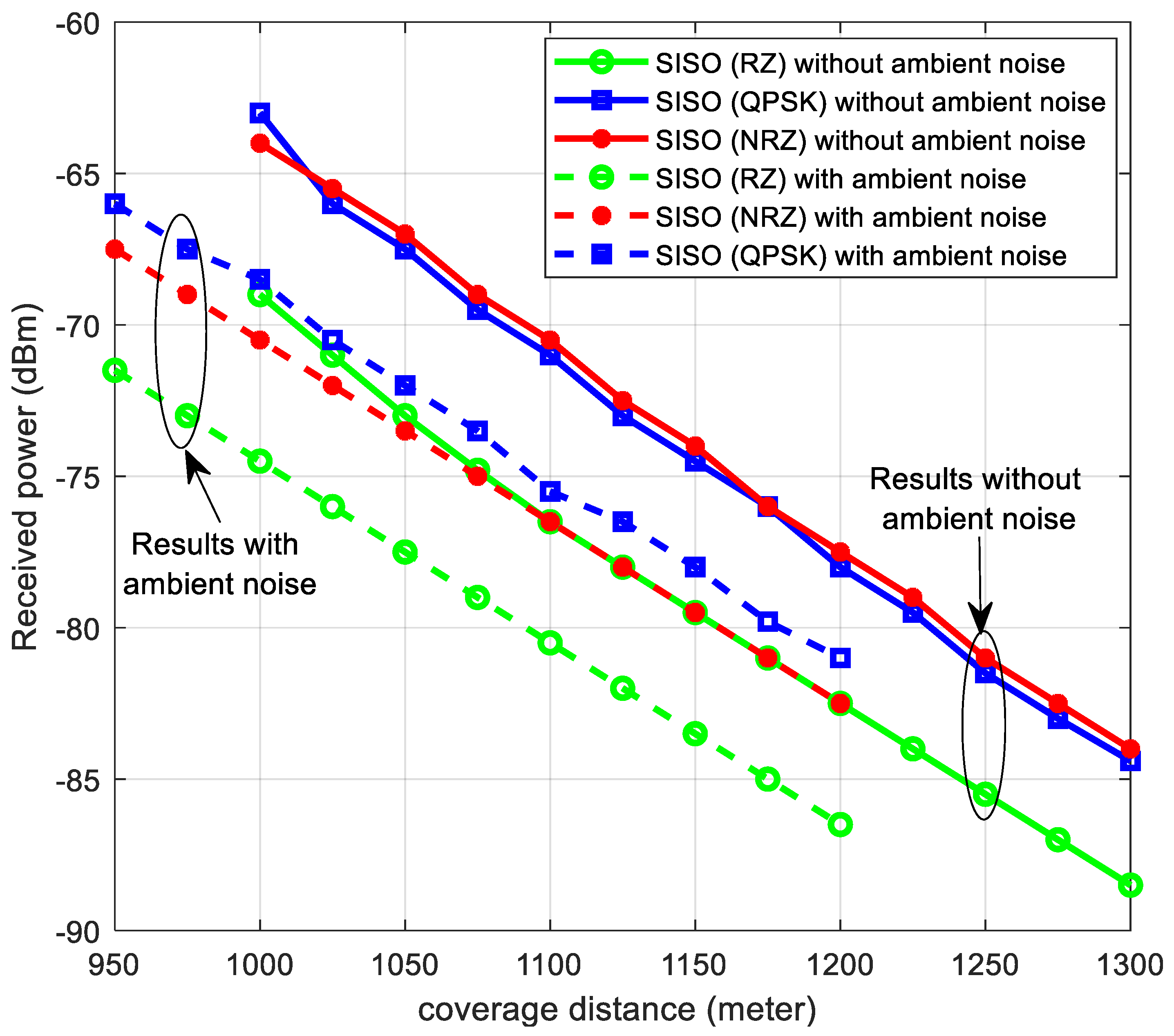

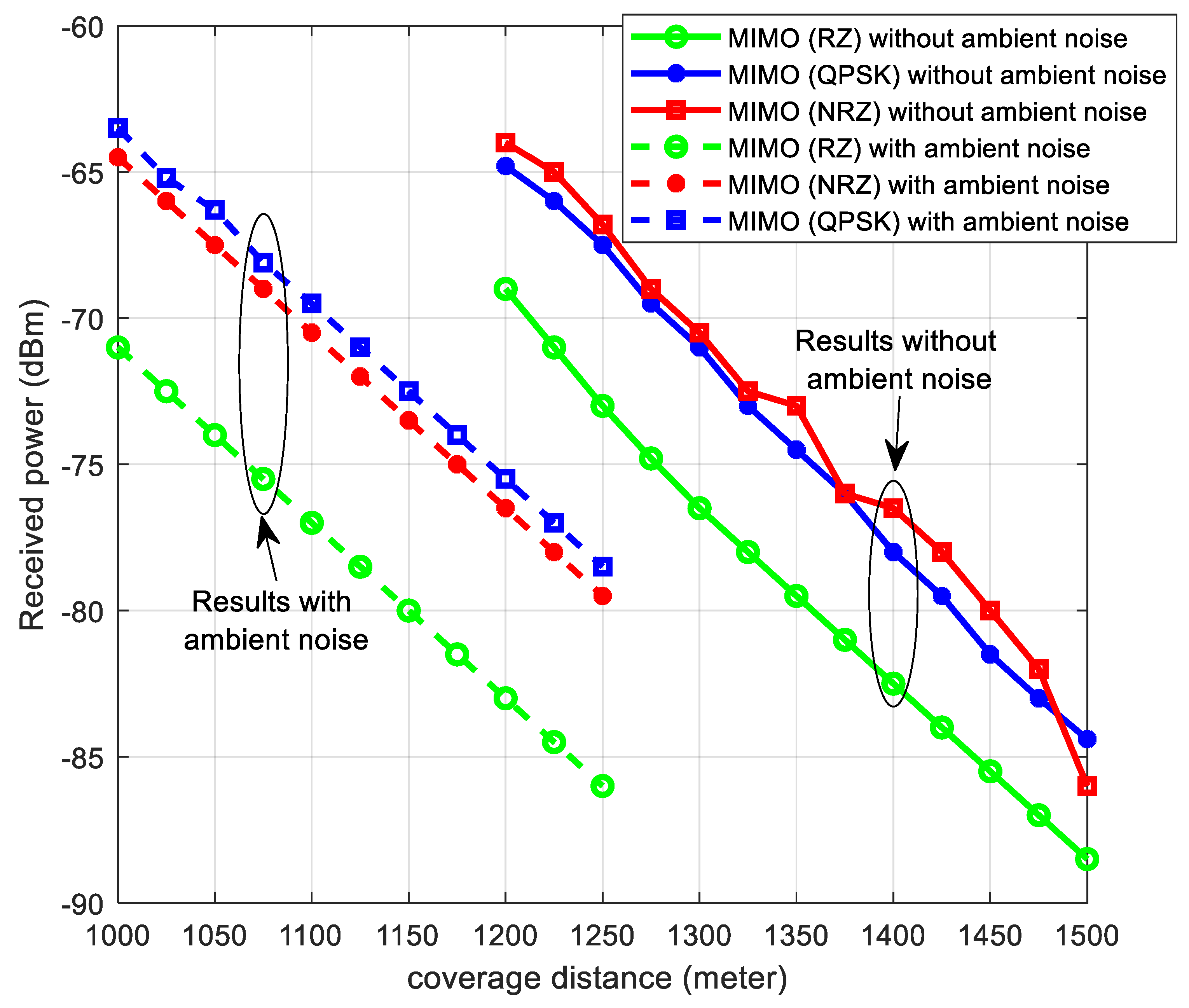

Figure 14 and Figure 15 illustrate the received power for SISO–VLC and MIMO–VLC systems, respectively, both with and without ambient noise. The effect of ambient noise is evident in the performance degradation. For the SISO–VLC system, the coverage distance decreases from 1087 m to 1020 m, a reduction of 6.2%. In the MIMO–VLC system, the coverage distance drops from 1280 m to 1105 m, marking a 13.6% reduction at a target received power of −70 dBm.

Figure 14.

Received power comparison for the SISO–VLC system with and without ambient noise.

Figure 15.

Received power comparison for the MIMO–VLC system with and without ambient noise.

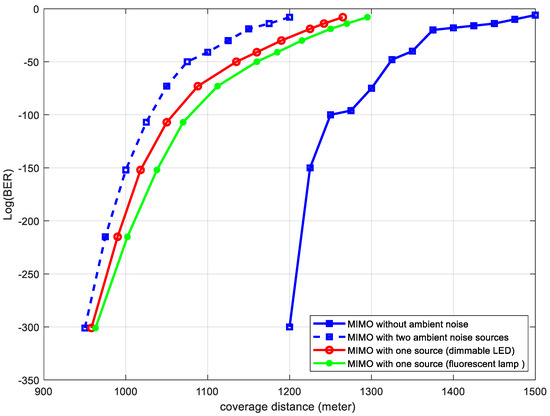

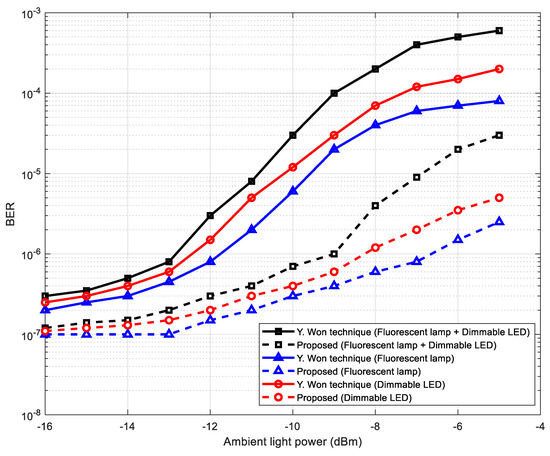

5.5. Effects of Different Ambient Light Sources

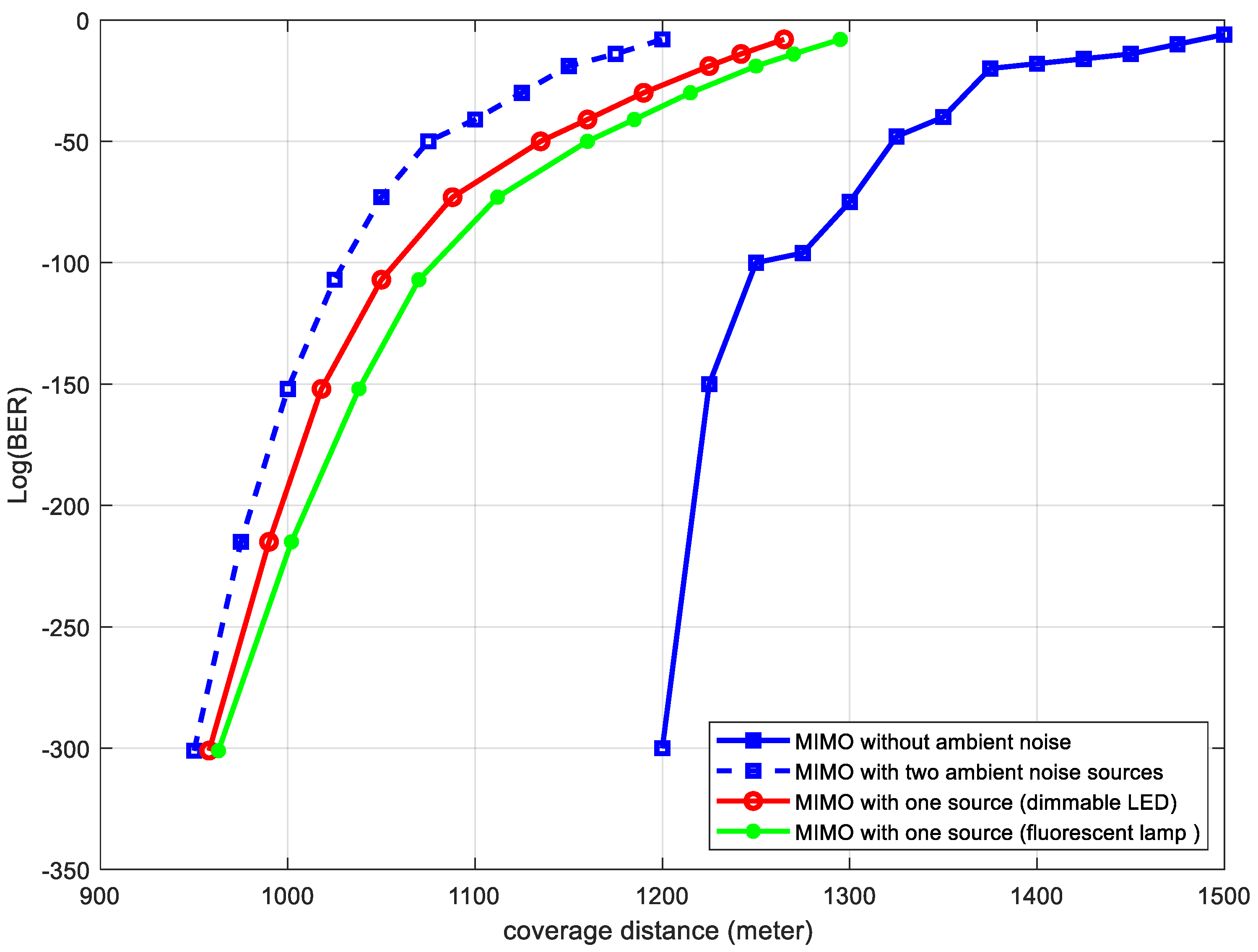

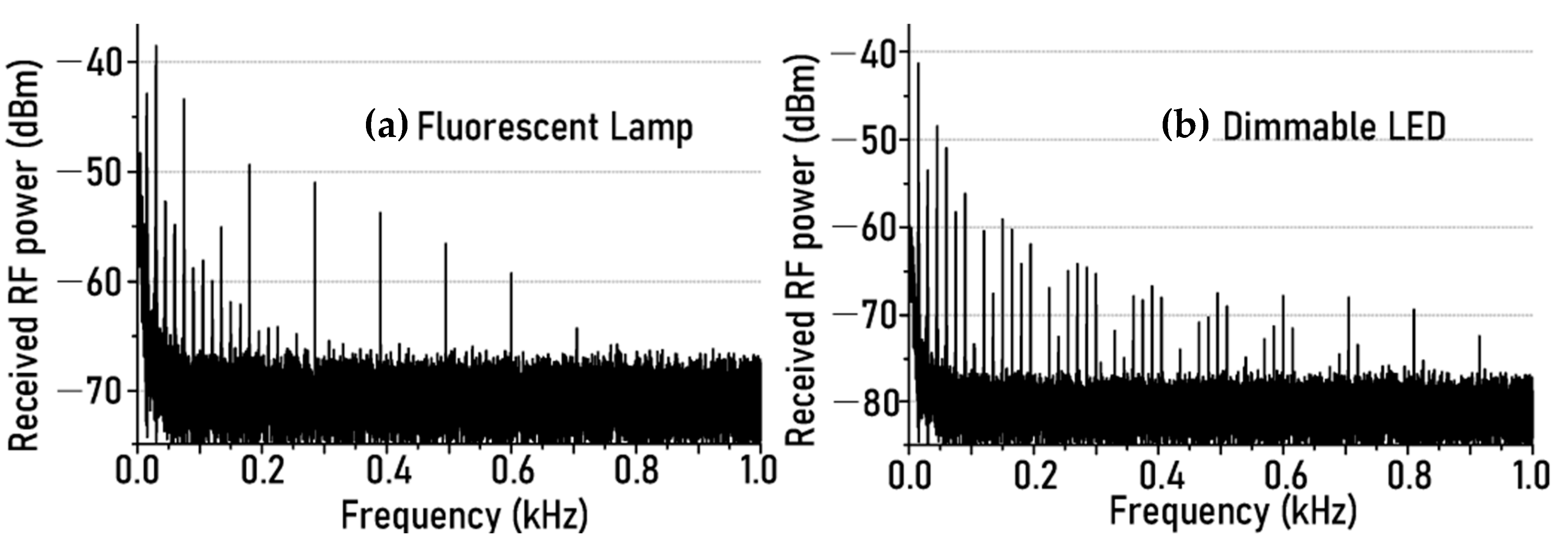

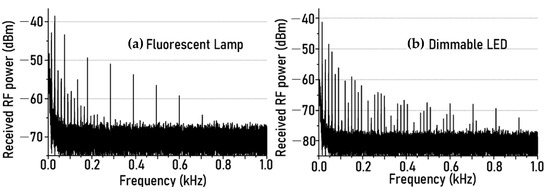

In the results above, the effects of two ambient noise sources (fluorescent lamps and dimmable LEDs) on the performance of the VLC systems were analyzed. This subsection examines the impact of noise generated by each source individually on the BER performance of the MIMO–VLC system using the QPSK technique.

To accurately evaluate the effect of ambient light interference on system performance, quantitative values for background light noise sources were incorporated into the simulation. Two typical ambient light sources were modeled: a fluorescent lamp and a dimmable LED, each contributing distinct interference characteristics. The optical noise power received at the photodiode from the fluorescent lamp was approximately 0.2 µW, corresponding to typical indoor lighting conditions (~500 lux). The dimmable LED introduced a stronger interference level of around 0.5 µW, reflecting brighter environments (~1000 lux) and accounting for pulse-width modulation flicker [15]. When both sources were active simultaneously, the total ambient noise power reached approximately 0.7 µW. These power levels were incorporated into the shot noise model using Equation (6), with the help of a photodetector responsivity R = 0.6 A/W and receiver bandwidth B = 1 GHz, to simulate realistic interference levels in the MIMO–VLC system.

As shown in Figure 16, the noise from the dimmable LED has a greater effect on BER performance compared to that from the fluorescent lamp. For instance, at a log(BER) of −50 dB, the coverage distance decreases from 9.3 m to 4.6 m, representing a 50.5% reduction when both noise sources are considered. However, when only the dimmable LED noise is considered, the coverage distance decreases from 9.3 m to 5.8 m, a reduction of 37.6%. Similarly, the noise from the fluorescent lamp alone reduces the coverage distance from 9.3 m to 6.2 m, corresponding to a 33.3% reduction. This greater impact of dimmable LED noise is due to the larger number of interference noise components, as illustrated by the radio frequency (RF) spectrum in Figure 17 [15]. This figure illustrates the RF spectrum of ambient light interference generated by both the fluorescent lamp and the dimmable LED. The dimmable LED shows a denser and more complex spectral profile, contributing more high-frequency noise components compared to the fluorescent lamp. These additional noise components increase the system’s susceptibility to interference when dimmable LEDs are present, particularly in higher data rate modulation schemes like QPSK.

Figure 16.

BER performance of the MIMO–VLC system using the QPSK technique under various ambient noise sources.

Figure 17.

The RF spectrum of fluorescent lamps and dimmable LED light sources.

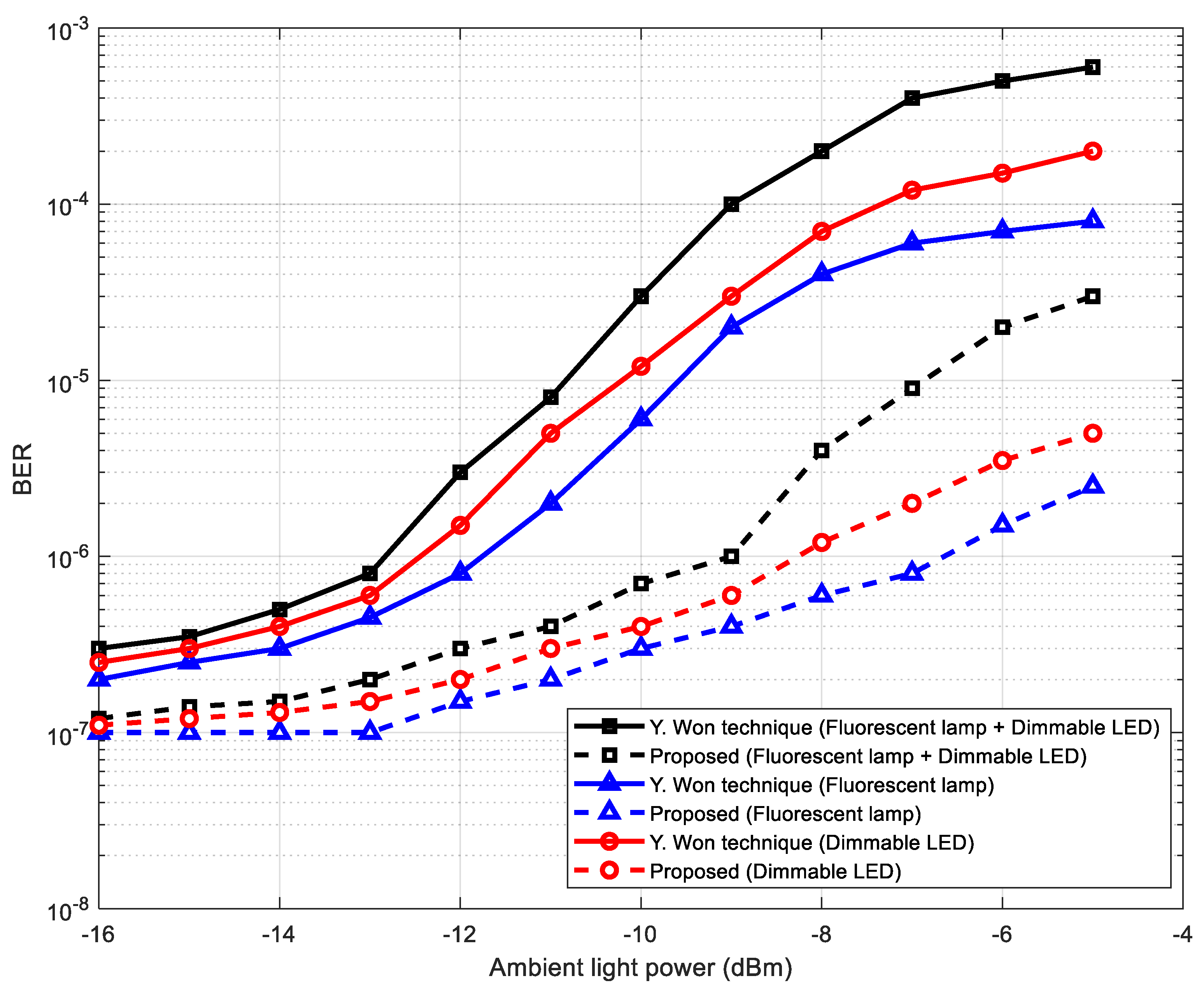

To validate the effectiveness of the presented MIMO–VLC system in realistic VLC environments, we compared it with the findings presented by Y. Won [15]. Figure 18 presents the BER performance as a function of ambient light power (dBm) under different lighting conditions, including fluorescent lamps and dimmable white LEDs. It can be observed that across all lighting scenarios, the presented MIMO–VLC system consistently achieves a lower BER under increasing ambient light power, demonstrating a clear improvement in system robustness. Notably, for combined fluorescent and LED interference at –6 dBm, the MIMO-VLC system achieves a BER below 10−4, while the Y. Won [15] suffers significant performance degradation.

Figure 18.

Comparison of BER performance versus ambient light power under various ambient lighting conditions.

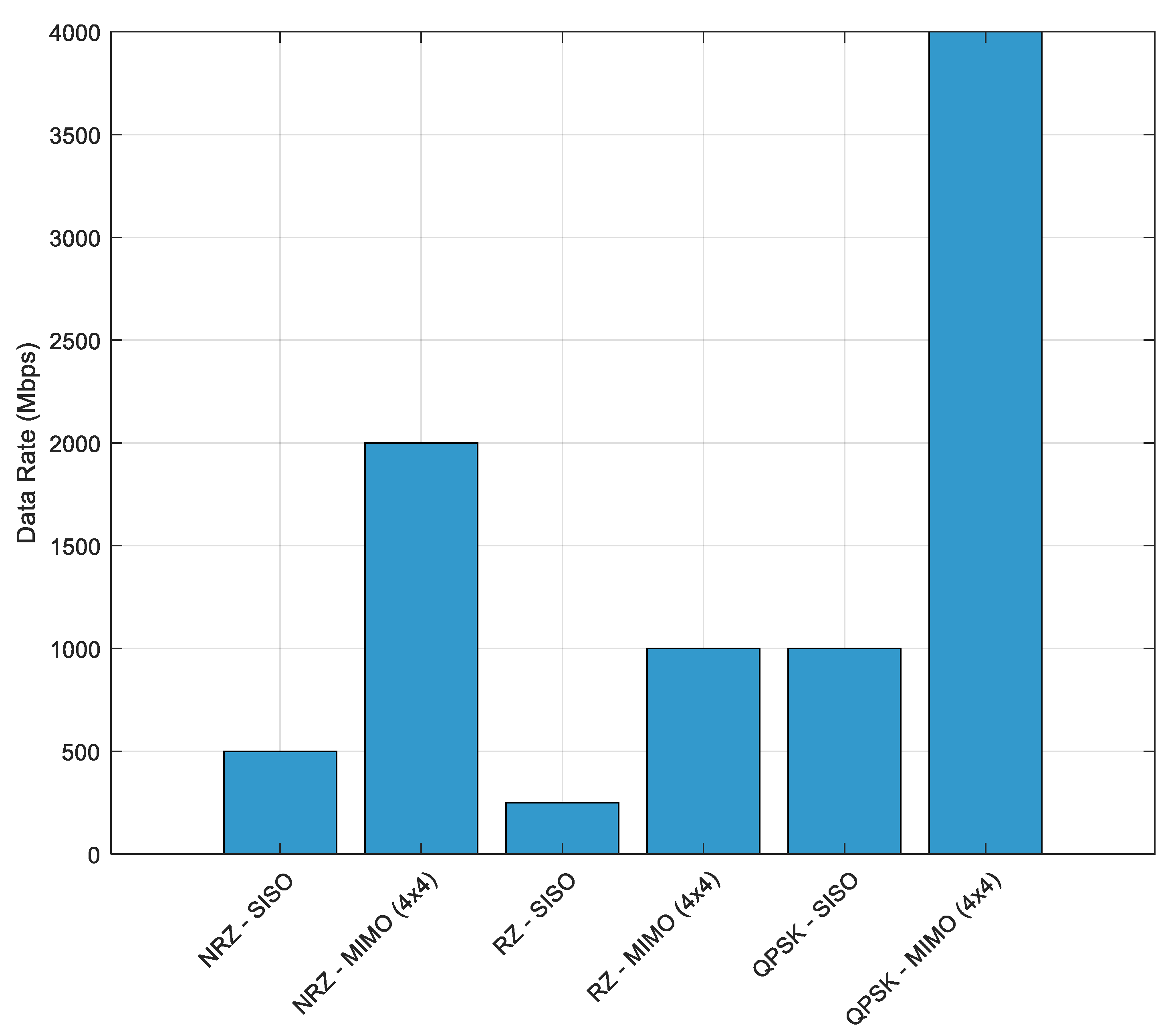

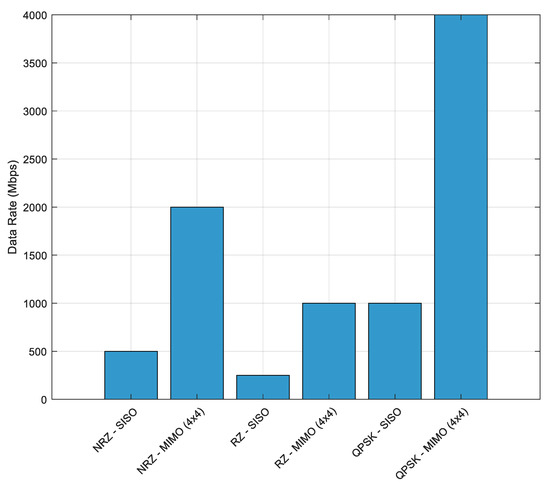

Figure 19 presents a comparison of the achievable data transmission rates for the considered modulation schemes under both SISO and MIMO configurations. The results demonstrate that QPSK outperforms both NRZ and RZ in terms of data rate due to its higher spectral efficiency, achieving up to 1000 Mbps in SISO and 4000 Mbps in MIMO (4 × 4) configurations. NRZ, with a spectral efficiency of 1 bit/symbol, provides a balanced performance with data rates of 500 Mbps (SISO) and 2000 Mbps (MIMO), making it a viable choice when both robustness and throughput are important. Conversely, RZ shows the lowest data rates (250 Mbps in SISO and 1000 Mbps in MIMO) due to its lower duty cycle and lower energy per symbol. The use of MIMO architecture significantly enhances data rate across all modulation schemes through spatial multiplexing, showing a 4-times increase in data rate compared to SISO when using 4 × 4 configurations.

Figure 19.

Comparison of data transmission rates for NRZ, RZ, and QPSK modulation schemes under SISO and MIMO configurations.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented a comprehensive analysis of MIMO–VLC systems using NRZ, RZ, and QPSK modulation techniques, evaluating their performance in both ambient light noise-free and noise-affected scenarios. The results demonstrated that MIMO-based VLC systems offer significant improvements in transmission range, BER, and received power compared to SISO systems, particularly when utilizing NRZ and QPSK modulation techniques. In the absence of ambient light interference, MIMO achieved longer transmission distances, with QPSK reaching up to 1450 m. However, ambient light noise caused performance degradation, with MIMO systems experiencing a 13.6% reduction in distance, while SISO systems saw a 6.2% reduction. Despite this, the advantages of MIMO diversity outweigh the performance losses, with MIMO consistently outperforming SISO across various metrics.

Future work could explore advanced techniques to mitigate ambient light interference further, such as adaptive filtering and advanced modulation schemes, to enhance the reliability and efficiency of MIMO-VLC systems under real-world conditions. Additionally, extending the study to include higher-order MIMO configurations and hybrid modulation techniques could provide deeper insights into optimizing VLC for high-performance applications in both indoor and outdoor environments. Plans are also underway to extend the system’s evaluation under more complex and dynamic scenarios, including experimental validations and further optimization of noise-cancellation techniques. Moreover, future simulations will incorporate the spatial dependency of ambient noise sources, potentially through radiometric modeling approaches, to more accurately reflect real-world lighting geometries and their effect on system performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.H.; Methodology, E.S.H.; Software, E.S.H.; Validation, A.J. and A.A.A.; Formal analysis, E.S.H.; Data curation, E.S.H.; Writing—original draft, E.S.H.; Writing—review & editing, A.J. and A.A.A.; Visualization, A.J. and A.A.A.; Supervision, E.S.H.; Funding acquisition, E.S.H., A.J. and A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, through Project Number JU-20250252-DGSSR-RP-2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VLC | Visible light communication |

| MIMO | Multiple-input, multiple-output |

| SISO | Single input, single output |

| NRZ | Non-return to zero |

| RZ | Return to zero |

| QPSK | Quadrature phase shift keying |

| OOK | On-off keying |

| LEDs | Light-emitting diodes |

| LASER | Light amplification by stimulated emission radiation |

| Li-Fi | light-fidelity |

| ITS | Intelligent transportation systems |

| FPGA | Field programmable gate arrays |

| V2V | vehicle-to-vehicle |

| I2V | infrastructure-to-vehicle |

References

- Sarbazi, E.; Kazemi, H.; Crisp, M.; El-Gorashi, T.; Elmirghani, J.; Richard, V.; Penty, R.V.; White, I.H.; Safari, M.; Haas, H. Design and Optimization of High-Speed Receivers for 6G Optical Wireless Networks. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2024, 72, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejan, M.A.S.; Rahman, M.H.; Aziz, M.A.; Kim, D.-S.; You, Y.-H.; Song, H.-K. A Comprehensive Survey on MIMO Visible Light Communication: Current Research, Machine Learning and Future Trends. Sensors 2023, 23, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, E.S. Three layer hybrid PAPR reduction method for NOMA-based FBMC-VLC networks. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2024, 56, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrakah, H.T.; Gutema, T.Z.; Sinanovic, S.; Popoola, W.O. PAPR Reduction in PAM-DMT based WDM VLC. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks and Digital Signal Processing (CSNDSP), Porto, Portugal, 20–22 July 2022; pp. 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrakah, H.; Gutema, T.; Offiong, F.; Popoola, W. PAPR Reduction in DCO-OFDM and PAM-DMT Based VLC Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO), San Jose, CA, USA, 15–20 May 2022; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Farid, S.M.; Saleh, M.Z.; Elbadawy, H.M.; Elramly, S.H. ASCO-OFDM based VLC system throughput improvement using PAPR precoding reduction techniques. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2023, 55, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, M.; Ren, X. Design and Implementation of Wireless Optical Access System for VLC-IoT Networks. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, K.; Shamim, M.h.M.; Abdur-Rouf, K. Visible light communication for intelligent transportation systems: A review of the latest technologies. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2021, 8, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ali, K.B. Intelligent Traffic System using Vehicle to Vehicle (V2V) & Vehicle to Infrastructure (V2I) communication based on Wireless Access in Vehicular Environments (WAVE) Std. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO), Noida, India, 13–14 October 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramudya, T.; Yudistira, R.P.; Trisnawan, M.A.; Setianingrum, L.; Wijayanto, Y.N.; Hamidah, M.; Dewi, M.F.; Firdaus, M.Y.; Rasuanta, M.P.; Rahmadiansyah, M.; et al. Transmitter and Receiver Design for Visible Light Communication System with Off-the-Shelf LED Towards its Implementation Possibility for Vehicle to Vehicle/Infrastructure (V2V/V2I) Communication. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Radar, Antenna, Microwave, Electronics, and Telecommunications (ICRAMET), Bandung, Indonesia, 15–16 November 2023; pp. 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georlette, V.; Moeyaert, V.; Bette, S.; Point, N. Visible Light Communication Challenges in the Frame of Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2020 22nd International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Bari, Italy, 19–23 July 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeeb, H.B.; Uysal, M. Visible Light Communication-Based Outdoor Broadcasting. In Proceedings of the 2021 17th International Symposium on Wireless Communication Systems (ISWCS), Berlin, Germany, 6–9 September 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, M.; Sökmen, Ö.G. Ambient Light Effect on Receiver for Visible Light Communication Systems. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2022, 35, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalami, F.M.; Haas, O.C.L.; Al-Kinani, A.; Wang, C.-X.; Ahmad, Z.; Rajbhandari, S. Impact of Dynamic Traffic on Vehicle-to-Vehicle Visible Light Communication Systems. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 3512–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, Y.-Y.; Yoon, S.M.; Seo, D. Ambient LED light noise reduction using adaptive differential equalization in Li-Fi wireless link. Sensors 2021, 21, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.S.; Abaza, M.; Mansour, A.; Alfalou, A. Performance Analysis of Power Allocation and User-Pairing Techniques for MIMO-NOMA in VLC Systems. Photonics 2024, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, M.; Verma, I.K.; Nag, P.; Goswami, S.; Singh, V. Performance Analysis of Indoor Visible Light Communication System Using NRZ-OOK Modulation Technique. In Advances in Smart Communication and Imaging Systems; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Agrawal, R., Kishore Singh, C., Goyal, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Huang, S.; Tavakkolnia, I.; Safari, M.; Haas, H. Spatial and Wavelength Division Joint Multiplexing System Design for MIMO-OFDM Visible Light Communications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 109526–109543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.-N.; Zhang, J. Spatial Constellation Design for MIMO Visible Light Communication Based on the Optimal Geometric Shaping. IEEE Photonics J. 2024, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.S. Multi-Carrier Communication Systems with Examples in MATLAB®: A New Perspective; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781498735322. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, E.S. Performance Enhancement and PAPR Reduction for MIMO based QAM-FBMC Systems. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Panayırcı, E. Physical Layer Security with MIMO-Generalized Space Shift Keying Modulation Technique in Li-Fi Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Mersin, Turkiye, 15–18 May 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Ren, X. Design and Implementation of More Than 50m Real-Time Underwater Wireless Optical Communication System. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 3654–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Jang, Y.M. Design of MIMO C-OOK using Matched filter for Optical Camera Communication System. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 13–16 April 2021; pp. 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjian, T.; Baghersalimi, G.; Ghassemlooy, Z. Performance Evaluation of a MIMO VLC System Employing Single Carrier Modulation with Frequency Domain Equalization. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd West Asian Symposium on Optical and Millimeter-Wave Wireless Communication (WASOWC), Tehran, Iran, 24–25 November 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Weng, J.-H.; Chow, C.-W.; Luo, C.-M.; Xie, Y.-R.; Chen, C.-J.; Wu, M.-C. 1.7 to 2.3 Gbps OOK LED VLC Transmission Based on 4 × 4 Color-Polarization-Multiplexing at Extremely Low Illumination. IEEE Photonics J. 2019, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivam, C.; Sharma, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, R. Performance Analysis of an Indoor Visible Light Communication System Using Optisystem Software. In Proceedings of the 2023 Third International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT), Bhilai, India, 5–6 January 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Atta, M.A.; Farmer, J.; Dawy, Z.; O’Brien, D.; Bermak, A. Multidomain Suppression of Ambient Light in Visible Light Communication Transceivers. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 18145–18154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai, M.; Sliti, M.; Boudriga, N. Access and resource reservation in vehicular Visible Light Communication networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 18th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Trento, Italy, 10–14 July 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichene, D.; Sliti, M.; Abdallah, W.; Boudriga, N. An aeronautical visible light communication system to enable in-flight connectivity. In Proceedings of the 2015 17th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Budapest, Hungary, 5–9 July 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Lee, K. Ambient light noise filtering technique for multimedia high speed transmission system in MIMO-VLC. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 34751–34765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesuthasan, F.H.; Rohitkumar, H.; Shah, P.; Trestian, R. Implementation and Performance Evaluation of a MIMO-VLC System for Data Transmissions. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Broadband Multimedia Systems and Broadcasting (BMSB), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 5–7 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Dong, Z.; Chen, Y. On Weighted Sum Rate of Multi-User Photon-Counting Multiple-Input Multiple-Output Visible Light Communication Systems under Poisson Shot Noise. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Das, S.; Videv, S.; Sparks, A.; Babadi, S.; Krishnamoorthy, A.; Lee, C.; Grieder, D.; Hartnett, K.; Rudy, P. 100 Gbps Indoor Access and 4.8 Gbps Outdoor Point-to-Point LiFi Transmission Systems Using Laser-Based Light Sources. J. Light. Technol. 2024, 42, 4146–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Hu, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, X.; Xia, L.; Liu, G.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Laser-Based Mobile Visible Light Communication System. Sensors 2024, 24, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Cai, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, C.; Chi, N. 11.2 Gbps 100-meter free-space visible light laser communication utilizing bidirectional reservoir computing equalizer. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 44315–44327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Zhu, X.; Liu, W.; Jia, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, A.; Zhang, M. Robust Wide-Angle Optical Wireless Communication System: From Design to Prototype. J. Light. Technol. 2025, 43, 3709–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).