Abstract

Digital holographic microscopy (DHM) provides numerous advantages, such as noninvasive sample analysis, real-time dynamic detection, and three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction, making it a valuable tool in fields such as biomedical research, cell mechanics, and environmental monitoring. To achieve more accurate and comprehensive imaging, it is crucial to capture detailed information on the microstructure and 3D morphology of samples. Phase processing of holograms is essential for recovering phase information, thus making it a core component of DHM. Traditional phase processing techniques often face challenges, such as low accuracy, limited robustness, and poor generalization. Recently, with the ongoing advancements in deep learning, addressing phase processing challenges in DHM has become a key research focus. This paper provides an overview of the principles behind DHM and the characteristics of each phase processing step. It offers a thorough analysis of the progress and challenges of deep learning methods in areas such as phase retrieval, filtering, phase unwrapping, and distortion compensation. The paper concludes by exploring trends, such as ultrafast 3D holographic reconstruction, high-throughput holographic data analysis, multimodal data fusion, and precise quantitative phase analysis.

1. Introduction

The concept of digital holography was first introduced by Professor Goodman in 1967, marking the beginning of holographic technology development [1]. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, digital holography faced significant challenges in realizing its full potential due to constraints in imaging hardware and computational power. In the 1990s, the development of high-resolution charge-coupled devices (CCDs) allowed CCDs to replace traditional photosensitive media, such as photographic and laser plates, for recording holograms. This shift enabled the use of digital methods to simulate optical diffraction, facilitating the full digitalization of both hologram recording and reconstruction.

Digital holographic microscopy (DHM) is a technology that combines traditional optical microscopy with holographic phase imaging techniques [2]. It provides benefits, such as noninvasive sample analysis, real-time dynamic detection, and three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction [3]. Furthermore, DHM allows for the quantitative measurement of a sample’s 3D morphological characteristics. This technology has found widespread use in fields such as biomedical research [4,5], cell mechanics studies [6], and environmental monitoring [7].

The goal of phase processing is to recover the complete phase information of an object from incomplete data, thereby obtaining its 3D shape and characteristics. However, traditional phase processing methods in DHM face several challenges, such as high computational complexity, poor resistance to noise, phase ambiguity, and limited real-time performance. Additionally, as the demand for higher resolution, increased imaging precision, and 3D imaging grows, issues such as larger data volumes, more complex scenes, and diverse equipment have become more prominent.

As noted by Rivenson et al., recent advancements in deep learning have led to significant progress in holography and coherent imaging by effectively addressing their inherent challenges while preserving their fundamental benefits [8]. Unlike traditional methods, deep learning-based phase processing techniques do not require prior knowledge and can automatically manage complex, nonlinear relationships. These methods have been progressively applied to various steps, such as phase retrieval [9], phase filtering [10], phase unwrapping [11], and phase distortion compensation [12]. Recently, the use of deep learning in solving phase processing challenges in DHM has become a major research focus in the field.

Deep learning, inspired by the structure and function of the human brain, utilizes deep neural networks composed of multiple layers of interconnected neurons through which information is propagated [13].

This paper provides a brief overview of the fundamental principles of DHM and emphasizes its potential advantages in addressing the challenges faced by traditional methods. It also examines the application of current deep learning methods in phase retrieval, phase filtering, phase unwrapping, and phase distortion compensation, while comparing the performance of various deep learning approaches. Furthermore, the paper highlights the limitations of existing methods and offers perspectives on future developments in the field, such as ultrafast 3D holographic reconstruction, high-throughput holographic data analysis, precise quantitative phase analysis, and multimodal data fusion. The aim is to offer valuable insights for advancing phase processing techniques in DHM.

2. Principles of Digital Holographic Microscopy

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Digital Holographic Microscopy

The evolution of quantitative phase imaging (QPI) technology began with the introduction of phase contrast microscopy in 1942, followed by a major breakthrough in holography in 1962, and the further development of digital holography in 1999. Over time, QPI has become a highly accurate imaging technique that is now widely applied in various fields, such as biomedical research and materials science.

QPI addresses the challenge of phase information loss in optical imaging by quantitatively measuring the changes in diffraction patterns or interference fringes caused by variations in the refractive index, thus extracting the phase information of the object [14].

Holographic microscopy (HM), a prominent technique within the QPI framework, works by combining a reference wave with an object wave to create interference, converting phase information into intensity, which is then captured in a hologram. When a reconstruction wave is used to illuminate the hologram, the phase and amplitude distribution of the object can be restored. With the development of CCDs and complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) sensors, hologram recording shifted from photographic plates to digital methods. The interference pattern is projected onto a high-resolution CCD or CMOS sensor for capture, and digital signal processing techniques are applied for decoding and reconstruction, allowing for the recording and reproduction of 3D object images [15].

2.1.1. Digital Holographic Microscopy Recording

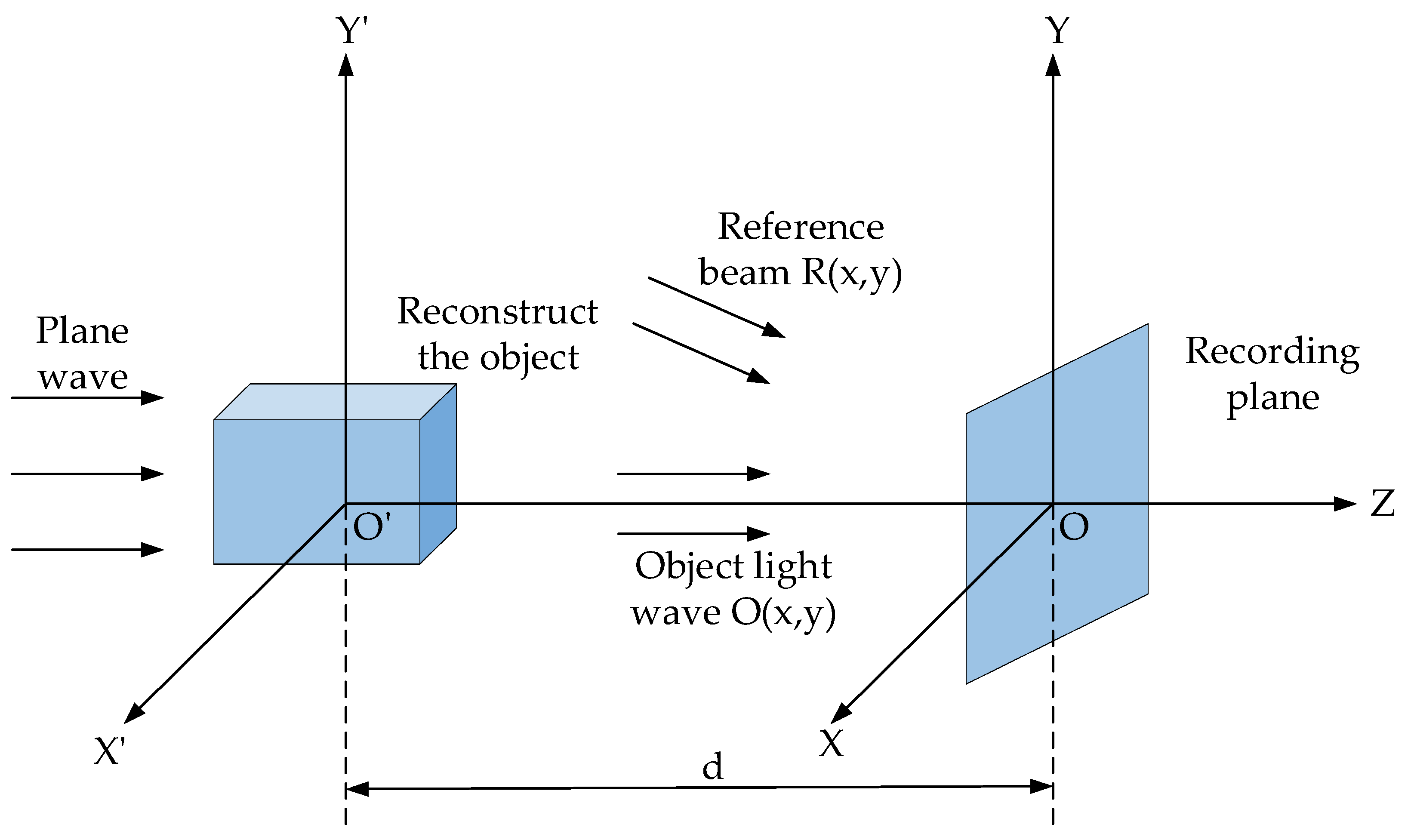

The measurement principle of digital holography follows the same basic concept as traditional optical holography, with the key difference being that digital holography utilizes an electronic imaging sensor instead of a traditional holographic plate to record a digital hologram. Figure 1 illustrates the optical path for recording a digital hologram. In this setup, X’0’Y’ represents the object plane, X0Y signifies the recording plane where the CCD photosensitive surface is located, and d indicates the recording distance of the digital holography system. When the object wave and reference wave are illuminated simultaneously, the hologram is captured by the CCD based on the principle of light interference, thereby achieving the digitalization of the hologram.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the digital holography recording process.

Let the object wave , generated on the object plane by the illumination of the observed object, and the reference wave , be represented by the following mathematical expressions:

where and denote the amplitudes of the object wave and reference wave, respectively; , where is the light’s wavelength; and θ is the angle between the reference wave and the z-axis.

The intensity distribution of the interference pattern created by the two waves at the recording plane is expressed as

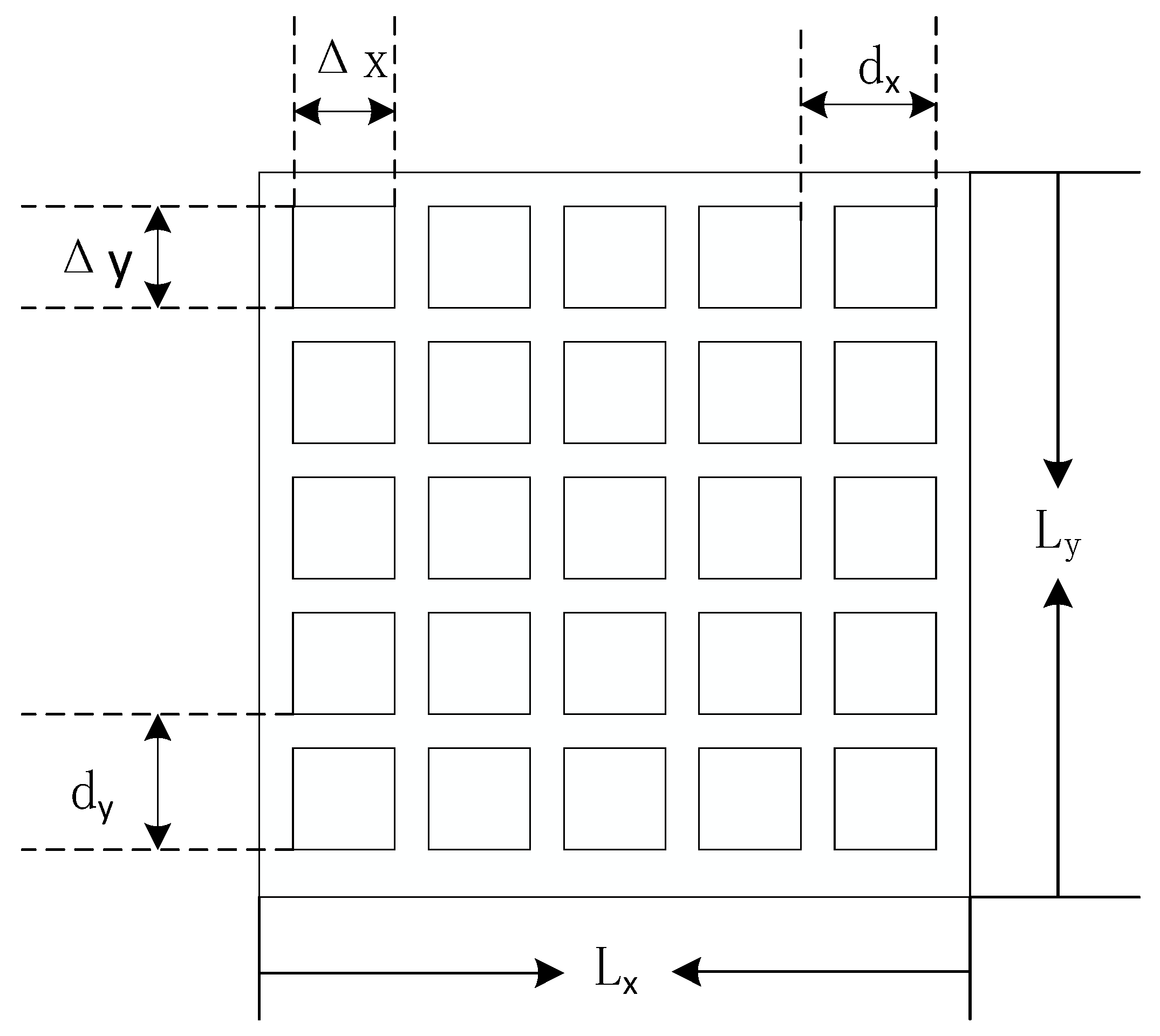

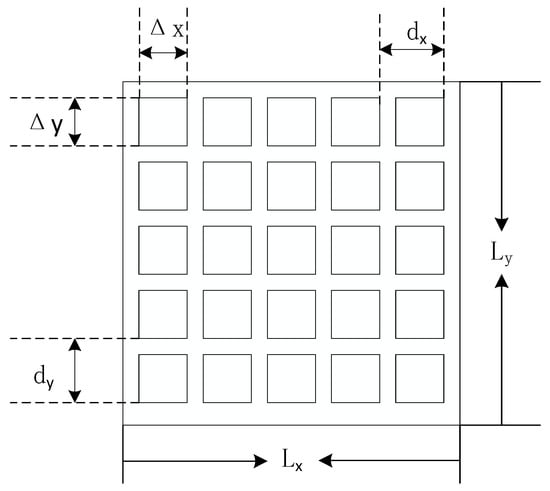

where and are the complex conjugates of the object wave and reference wave, respectively. The CCD captures the interference light intensity and converts it into an electrical signal. The structural schematic of the CCD is presented in Figure 2. Let the dimensions of the CCD’s photosensitive surface be and , the pixel size be , the number of pixels be , and the pixel interval be , where and . The discretized interference intensity recorded by the CCD can then be expressed as

where p and q refer to integers within specified ranges and , and signifies a two-dimensional Dirac delta function, which is an extension of the one-dimensional Dirac delta function, . The one-dimensional Dirac delta function, , is defined as . The two-dimensional Dirac delta function, , can be formulated as the product of two one-dimensional delta functions: . Finally, the hologram recorded by the CCD is stored as a numerical matrix in the computer.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the CCD image sensor structure.

2.1.2. Digital Holographic Microscopy Reconstruction

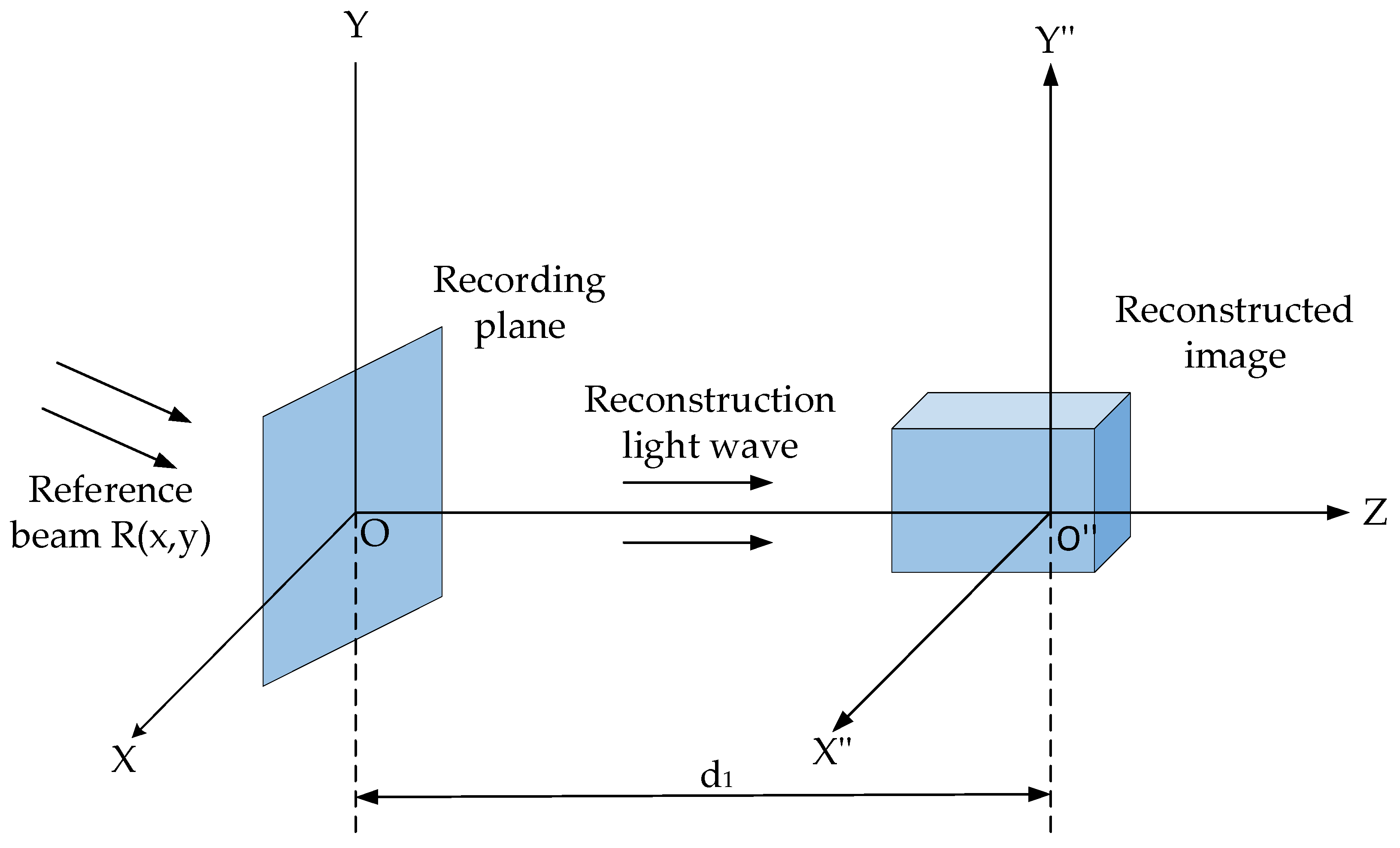

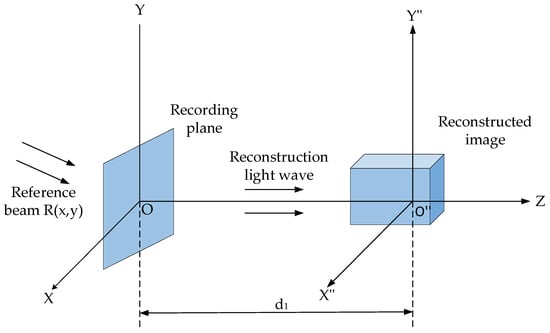

The digital holography reconstruction process involves digitizing the recorded interference image and inputting it into a computer system. The computer then simulates the illumination of the hologram by light waves and the diffraction of emitted light reaching the observation plane. This allows for the calculation of both the intensity and phase information of the object being measured. Figure 3 illustrates the hologram reconstruction process, where the hologram is positioned in the XOY plane, and the reconstructed image is in the X″O″Y″ plane. The distance d1 represents the reconstruction distance.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the digital holographic reconstruction process.

Let the complex amplitude of the light wave after illuminating the hologram be denoted as . During the reconstruction process, a numerical reconstruction algorithm is employed to obtain the complex amplitude of the object wave at the image plane, denoted as . From the complex amplitude distribution, the intensity and phase of the reconstructed image can then be calculated as follows:

where and denote the imaginary and real parts of , respectively. Since the phase calculated using the arctangent function is wrapped within the range [], phase unwrapping is necessary to recover the true phase of the object.

2.2. Signal Changes in Phase Processing

Phase processing is a critical aspect of DHM, encompassing several key steps, such as phase recovery, filtering, phase unwrapping, and distortion compensation. These processes together guarantee the quality and precision of the imaging results.

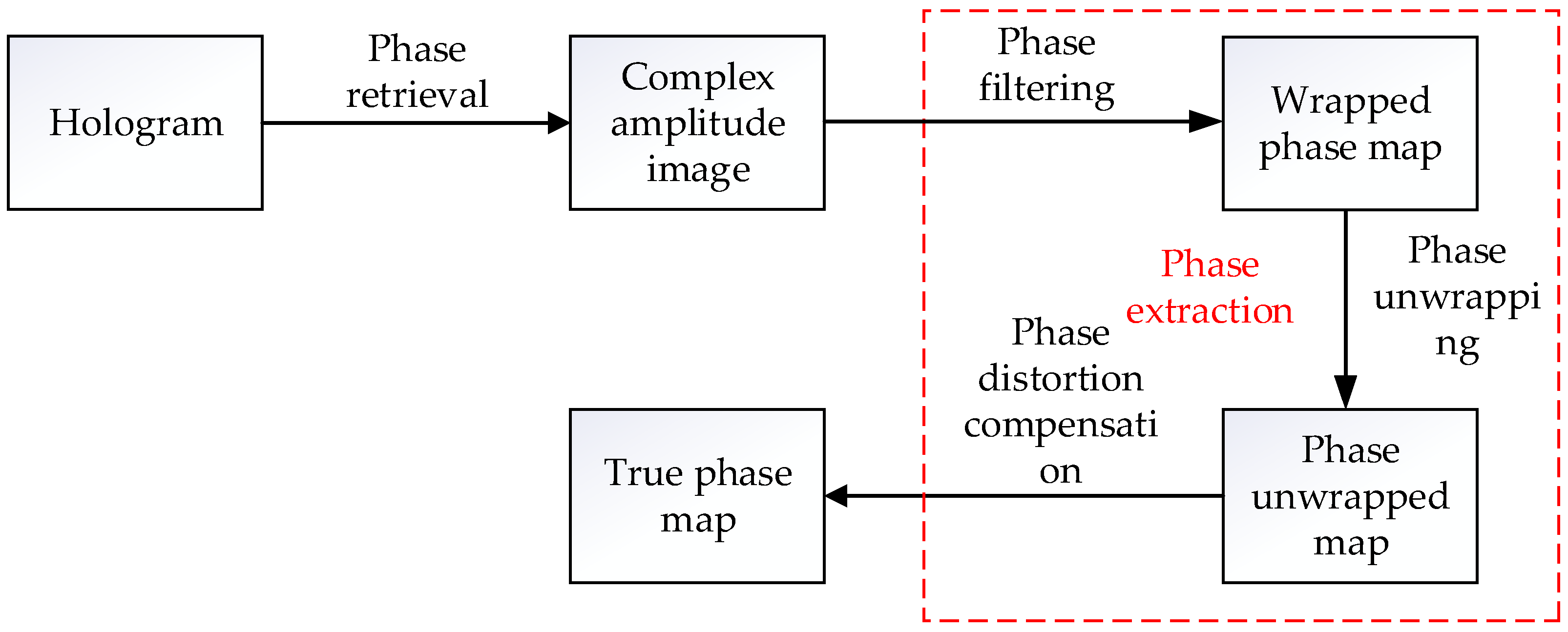

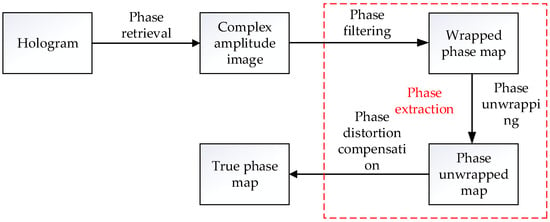

As illustrated in Figure 4, which presents a flowchart for phase processing steps in DHM, the red dashed section is designed as phase extraction. This phase extraction process involves three main steps: phase filtering, phase unwrapping, and phase distortion compensation.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of phase processing.

In the phase recovery step, the intensity of the recorded interference light field is extracted using Equation (3). DHM algorithms, Fourier transform, or deep learning techniques are then applied to recover the phase information, allowing the complex amplitude to be computed, which encompasses both intensity and phase. The phase that needs to be recovered is denoted as .

In the phase filtering step, the process involves applying a Fourier transform to convert the complex amplitude into the frequency domain, performing the filtering operation, and subsequently transforming it back to the spatial domain. Suppose the complex amplitude is processed with the frequency domain filter , resulting in .

where implies the frequency domain representation of and implies the frequency domain filter. denotes the inverse Fourier transform.

After phase filtering, the updated phase information can be extracted from , and its expression is denoted as

where represents the intensity information of the object wave after filtering, and denotes the phase information after filtering.

During phase unwrapping, the unwrapped phase information is given by

where signifies an integer function, indicating the integer multiple of 2π that should be added during the phase unwrapping process. The complex amplitude following phase unwrapping is expressed as

In the phase distortion compensation step, assuming that the unwrapped phase contains a certain known phase distortion , the phase information after distortion compensation, , can be expressed as

The complex amplitude after distortion compensation can be expressed as

where denotes the estimated aberration.

Following the above steps, the phase complex amplitude can be represented as

where indicates the phase information derived from the difference between the phase after distortion compensation and the original signal during the phase processing. Finally, the real phase obtained through phase processing is

2.3. Theoretical Framework for Phase Processing in Deep Learning

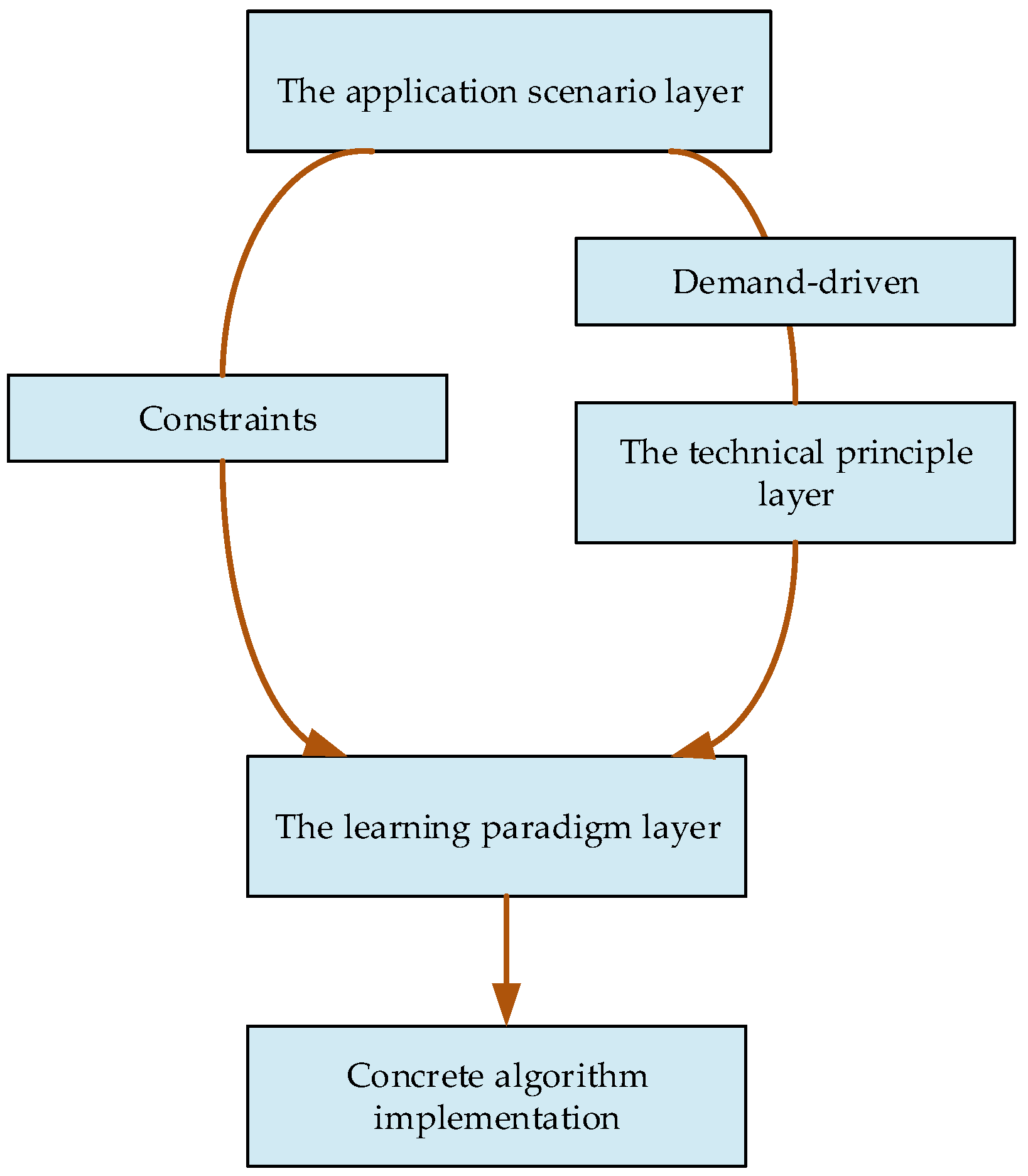

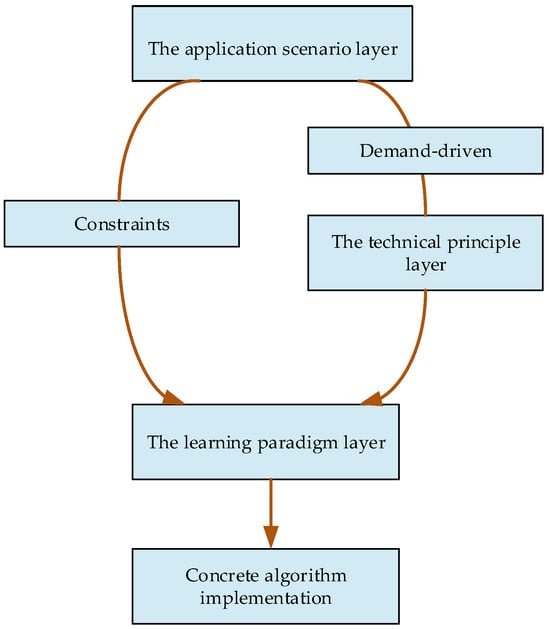

Figure 5 introduces a structured, three-layer classification framework designed to clarify how deep learning techniques are applied to DHM phase processing across three dimensions: the application scenario layer (e.g., biomedical, materials science), the technical principle layer (data-driven, model-driven, hybrid), and the learning paradigm layer (supervised, unsupervised, self-supervised learning).

Figure 5.

Theoretical framework for phase processing in digital holographic microscopy.

Additionally, the theoretical framework for deep learning-based phase processing is structured into four hierarchical layers: the application scenario, technical principle, learning paradigm, and algorithm implementation.

2.3.1. Application Scenario Dimension

From the perspective of application scenarios, deep learning-based phase processing in DHM serves distinct roles across fields. In biomedical research, it enables label-free, dynamic analysis of biological samples by suppressing phase noise and reconstructing 3D structures for high-resolution, long-term live-cell tracking.

In materials science, deep learning-based phase processing facilitates the extraction of microstructural features, such as crystal orientations and interfacial defects, supporting process optimization and performance prediction for advanced materials.

While both fields rely on precise phase analysis at the microscale, biomedical applications emphasize non-destructive monitoring of dynamic processes, whereas materials science focuses on high-throughput analysis of static structure–property relationships.

2.3.2. Technical Principle Dimension

From the perspective of technical principles, three paradigms have been adopted in DHM phase processing using deep learning. In the data-driven paradigm, models are trained on large annotated datasets to automatically learn phase reconstruction mapping relationships from raw holograms. This approach, reliant on data volume and model capacity, is suited for data-rich scenarios involving complex, non-explicit physical mechanisms.

In the physics model-driven paradigm, optical priors, such as light wave propagation and diffraction theory, are embedded into model structures or loss functions. By incorporating physical constraints or differentiable simulation modules, model outputs are aligned with underlying physical laws. This paradigm offers greater interpretability and generalization, particularly in data-limited cases with well-defined physics.

The hybrid paradigm combines both strategies. Deep learning is used to model nonlinearities and noise, while physical constraints are introduced—e.g., via wave equation regularization terms based on wave equations to neural networks. This method enhances phase reconstruction accuracy while preserving physical consistency, making it well-suited for biomedical and materials science applications demanding both high precision and interpretability.

2.3.3. Learning Paradigm Dimension

The characteristics of the three learning paradigms are discussed in what follows.

Supervised learning involves training models on large volumes of annotated data to directly learn the mapping between inputs and corresponding outputs. The accuracy of such models is highly dependent on both the quality and quantity of the annotations provided. In applications requiring phase continuity constraints, loss functions are employed to enforce consistency between the model’s output and the continuous phase of the target labels.

Unsupervised learning performs phase unwrapping by harnessing the intrinsic structure of the data, thereby eliminating the need for annotated datasets. This approach is particularly suitable for scenarios where annotation is costly or prior domain knowledge is scarce. Phase continuity constraints are implemented by designing prior constraints or leveraging the intrinsic structure of the data.

Self-supervised learning automatically circumvents manual annotation by constructing supervisory signals through proxy tasks designed directly from unlabeled data. Incorporating physical priors improves the model’s generalization to unseen samples. Phase continuity constraints are enforced either through transformations—such as rotation or occlusion—that require consistent phase predictions, or by leveraging phase correlation across multi-frame images or data from different sensors.

3. Application of Deep Learning in Phase Recovery of Digital Holographic Microscopy

Phase information is essential for reconstructing the 3D structure and complex details of an object. However, direct measurement of phase information from a hologram is not possible. Phase retrieval techniques reconstruct the object’s phase from the recorded holographic intensity, forming the foundation for subsequent phase reconstruction and 3D imaging from indirect or incomplete data. This process enhances image quality and contrast while enabling the analysis of internal structures and dynamic changes in the object. Traditional phase retrieval methods, such as the Gerchberg–Saxton algorithm [16] and the Fienup algorithm [17], have robust anti-interference capabilities. However, they face the following limitations:

- (1)

- They rely on iterative calculations, which are time-consuming and inefficient.

- (2)

- The complex operational processes lead to lower-quality reconstructed images.

- (3)

- They require that the intensity and phase be processed separately in sequential steps, as they lack an integrated framework for efficient joint reconstruction.

To address the issue (1), Zhang et al. from Tsinghua University proposed a model in 2018 based on a U-shaped (U-Net) convolutional neural network (CNN) [18]. This model incorporates the U-Net structure, enabling faster recovery of the original phase of the sample and replacing traditional iterative methods, thus reducing computation time. However, this study did not provide specific evaluation metrics.

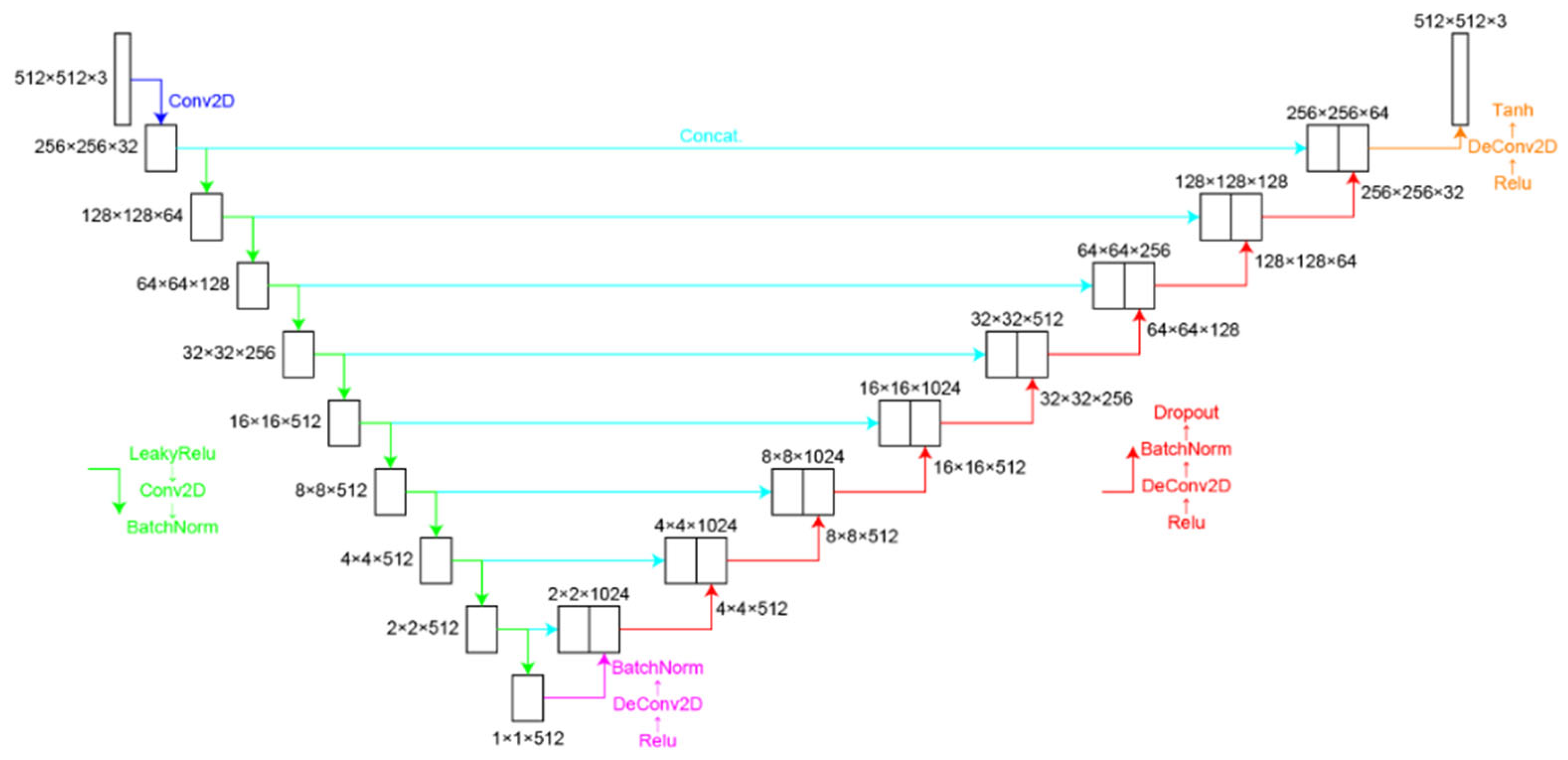

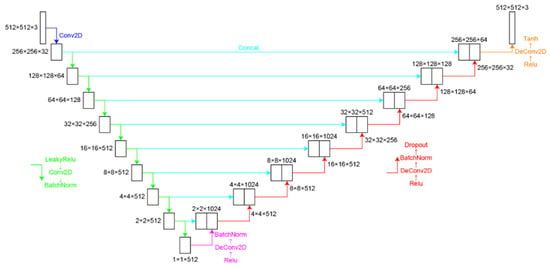

To address the issue (2), Yuki Nagahama from the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology introduced a phase retrieval method using a U-Net network model in 2022 [19]. Figure 6 depicts the U-Net CNN model. This approach can process a single hologram, significantly simplifying the process, effectively removing overlapping conjugate images, and enhancing the quality of reconstructed images. In terms of the evaluation metric mean absolute error (MAE), this method reduces the error by 0.058–0.069 π compared to traditional methods. However, comparisons of this method to other deep learning models were not provided.

Figure 6.

U-Net CNN model [19], where green line represents the combination of LeakyRelu + Conv2D + BatchNorm, pink line represents the combination of Relu + DeConv2D + BatchNorm, red line represents the combination of Relu + DeConv2D + BatchNorm + Dropout, and orange line represents the combination of Relu + DeConv2D + Tanh.

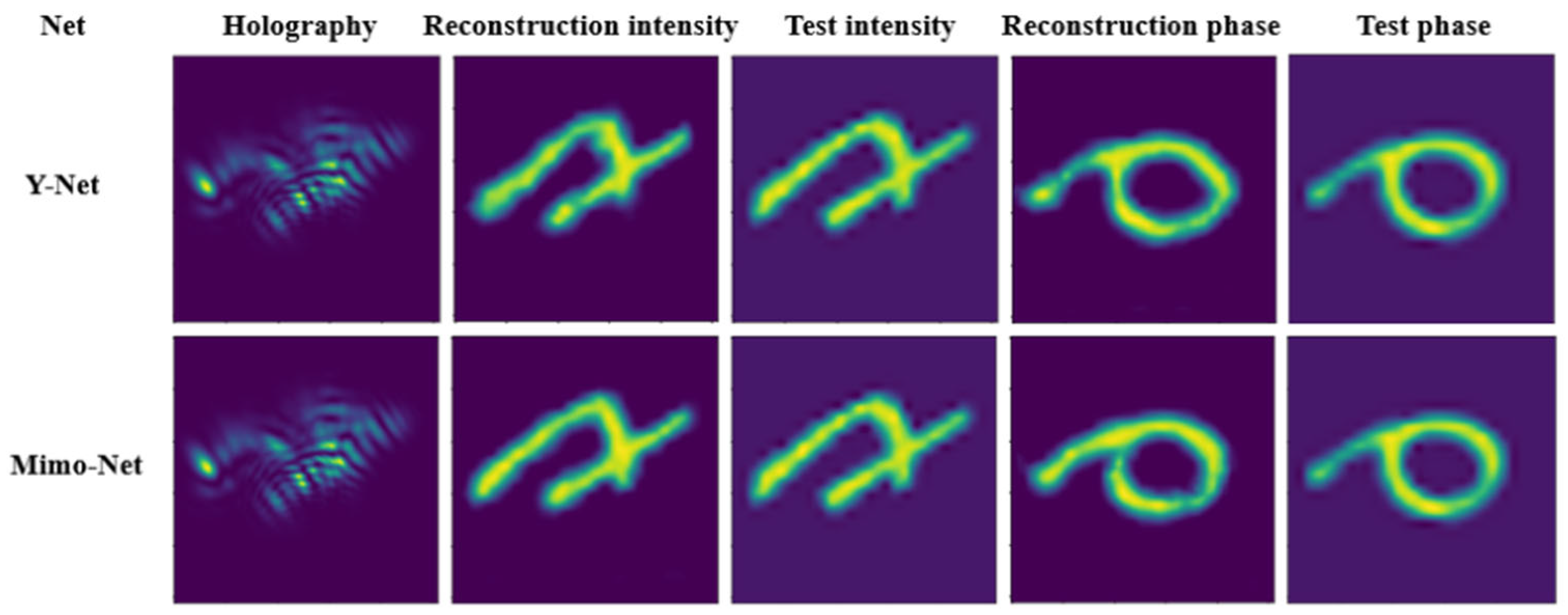

To address the issue (3), Wang et al. from Northwestern Polytechnic University proposed the one-to-two Y-Net network in 2019 [20]. This network was developed to simultaneously reconstruct both intensity (light intensity distribution) and phase information from a single digital hologram. However, the Y-Net network requires three rounds of training, which affects its training efficiency and necessitates further optimization.

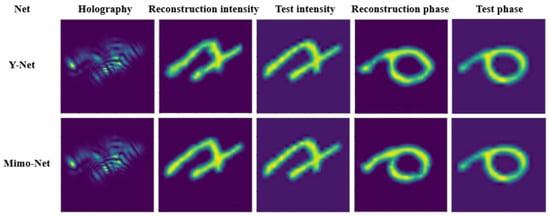

In 2023, Chen et al. from the North China University of Science and Technology proposed the Mimo-Net network [21], which requires only a single training session to simultaneously reconstruct intensity and phase information at three different scales. Compared to Y-Net [20], Mimo-Net offers superior reconstruction performance in terms of image quality. Figure 7 compares the reconstruction results of Mimo-Net and Y-Net at the same scale of 256 × 256.

Figure 7.

Comparison of network reconstruction results between Mimo-Net and Y-Net at a 256 × 256 scale [21].

To provide a structured overview of phase processing research, the subsequent analysis is organized across multiple dimensions. Table 1 classifies existing phase recovery networks, highlighting structural design principles that impact phase recovery performance. Table 2 compares the core mechanisms, advantages, and disadvantages of phase recovery algorithms, distilling key insights to validate algorithmic applicability across diverse scenarios.

Table 1.

Classification of phase recovery networks across key dimensions.

Table 2.

Comparison of advantages, disadvantages, and mechanisms analysis of phase recovery algorithms.

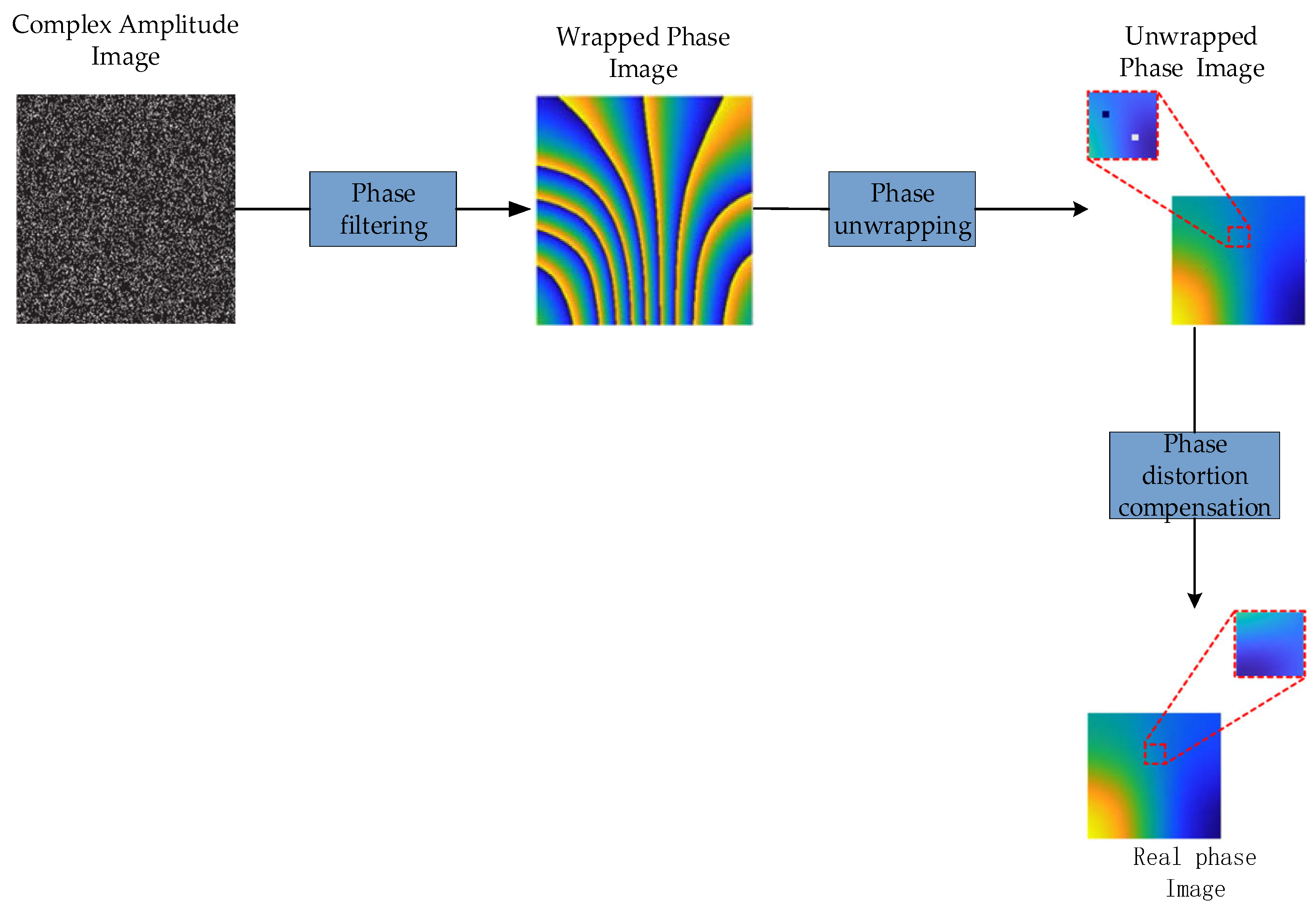

4. Application of Deep Learning in Phase Extraction for Digital Holographic Microscopy

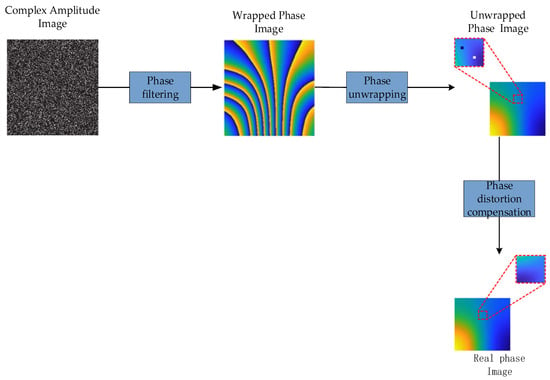

Figure 8 illustrates the process of phase extraction in DHM, which involves three key steps: phase filtering, phase unwrapping, and phase distortion compensation. The phase extraction process begins with phase retrieval to acquire the complex amplitude image. This image is then subjected to phase filtering to produce the wrapped phase map. Subsequently, phase unwrapping is performed on the wrapped phase map to generate the phase unwrapping map. Finally, phase distortion compensation is applied to the unwrapped phase map to obtain the final real phase information.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of phase extraction, where the red dashed box represents local magnification.

4.1. Application of Deep Learning in Phase Filtering

Phase information obtained through phase retrieval can be affected by high-frequency noise or artifacts due to environmental noise, optical system limitations, or computational errors. These noises can cause the phase images to become unstable or distorted. Phase filtering helps remove such unwanted noise, smooth the phase map, and optimize its spatial distribution, effectively reducing artifacts and minimizing imaging errors caused by noise.

Traditional speckle noise filtering methods are divided into spatial domain, transform domain, and deep learning-based techniques, based on their theoretical foundations and processing stages. Spatial domain filtering methods include median filtering [22], mean filtering [23], blind convolution filtering [24], block matching [25], and 3D filtering [26], while transform domain methods include Wiener filtering [27], windowed Fourier transform [28], and wavelet filtering [29]. Although these methods classify and process objects, several challenges remain in practice:

- (1)

- Difficulty in obtaining noise-free phase maps for labeling.

- (2)

- Unclear feature representation.

- (3)

- Inefficient in denoising.

Recent studies have shown that deep learning approaches enable robust single-image super-resolution without iterative processing, greatly enhancing the speed of high-resolution hologram acquisition and reconstruction.

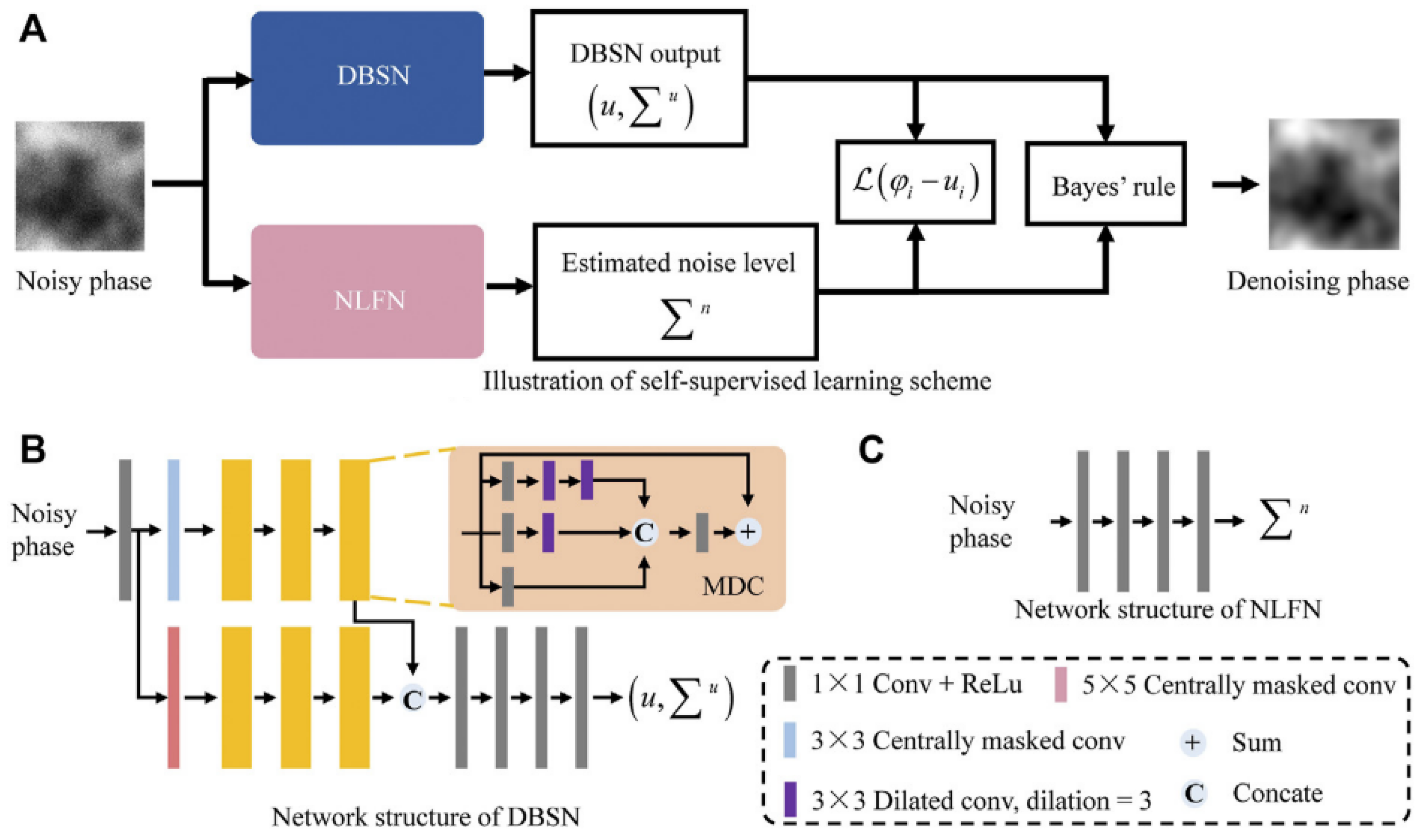

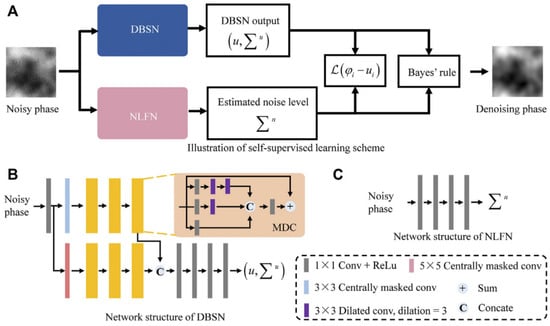

To address the issue (1), Wu et al. from Guangdong University of Technology proposed a network comprising a deep bilateral network (DBSN) and a non-local feature network (NLFN) in 2022 [30]. The framework of the DBSN and NLFN network is shown in Figure 9. The network is trained using a self-supervised loss function and outperforms traditional median filtering, block-matching, and 3D filtering in noise removal, providing superior noise suppression and generating noise-free phase maps.

Figure 9.

Network framework diagrams of DBSN and NLFN [30], where (A) represent the self-supervised learning scheme, (B) represent the DBSN network model, and (C) represent the NLFN network model.

To address the issue (2), Tang et al. from Zhejiang University of Science and Technology (2024) identified the high similarity between digital holographic mixed phase noise (DHHPN) and Perlin noise and proposed a deep learning-based continuous phase denoising method utilizing this similarity [31]. This approach not only resolved challenges associated with experimental data collection and labeling but also improved the generalizability of the trained CNN model across different DHM systems, effectively addressing unclear feature representation.

In 2025, Awais et al. proposed a lightweight wrapped-phase denoising network, WPD-Net [32], that enhances feature selection capability in noisy regions through residual dense attention blocks (RDABs), thereby providing an efficient solution for real-time biomedical imaging.

The Table 3 below presents an analysis and comparative summary of the mechanisms of deep learning and traditional methods for phase filtering, focusing on the challenges in acquiring noise-free phase labels and unclear feature representations.

Table 3.

Mechanism analysis and comparison of traditional methods and deep learning algorithms for phase filtering, focusing on the challenges in acquiring noise-free phase labels and unclear feature representations.

To tackle the issue (3), Fang et al. from the Kunming University of Science and Technology (2022) introduced a deep learning-based speckle denoising algorithm using conditional generative adversarial networks (cGANs) [33], which enhanced feature extraction and denoising performance. In 2023, they integrated the Fourier neural operator into the CNN model [34], proposing the Fourier-UNet network. This architecture boosted denoising accuracy while reducing the number of training parameters. In 2024, they further enhanced their model by incorporating a 4-f optical speckle simulation module into the CycleGAN network [35]. This approach eliminated the need for pre-labeled paired data, improving both training accuracy and speed, and resulting in a 6.9% performance improvement over traditional methods when applied to simulated data. Figure 10 compares various methods with those reported in [24] for speckle noise denoising performance.

Figure 10.

Comparison of speckle noise image denoising using different methods [35].

The Table 4 below presents an analysis and comparative summary of the mechanisms of deep learning and traditional methods for phase filtering, focusing on denoising inefficiencies.

Table 4.

Mechanism-level analysis and comparison of deep learning algorithms for phase filtering, focusing on denoising inefficiencies.

The Table 5 below presents a classification and comparative summary of deep learning and traditional methods for phase filtering.

Table 5.

Classification of phase filtering network dimensions.

The Table 6 below presents a comparative analysis of deep learning methods for improving phase filtering denoising effects.

where denote the true and predicted values of the sample, respectively. represents the maximum value of the image point color, which is 255 when each sample point is represented by 8 bits. and represent the mean values of images X and Y, respectively. and are the variances of images X and Y, respectively. indicates the covariance between images X and Y, and and are constants.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of deep learning methods for enhancing denoising performance in phase filtering.

In phase filtering, spatial frequency serves as a key metric for assessing the effectiveness of denoising. Equations (21) and (22) define the row frequency and column frequency, which quantify the frequency variations along the row and column directions of an image, respectively. Equation (23) combines row frequency and column frequency to compute the overall spatial frequencies, providing a comprehensive measure of the image’s frequency distribution.

Currently, deep learning-based denoising techniques are confronted with challenges, such as limited accuracy, high reliance on data, poor generalization, substantial computational demands, and model complexity. Future research is expected to focus on enhancing adaptability, improving accuracy, and simplifying model architectures to address these limitations.

4.2. Application of Deep Learning in Phase Unwrapping

After phase filtering, phase values are often confined within the 2π periodic range, resulting in jumps or discontinuities in the phase signal , . The goal of phase unwrapping is to remove these periodic jumps, enabling the phase variation to represent a continuous and physically plausible process. This process involves sequentially correcting the phase data to eliminate errors introduced by periodic constraints, thereby ensuring an accurate representation of the object’s surface morphology and subtle phase variations.

Traditional phase unwrapping techniques are generally categorized into time phase unwrapping (TPU) and spatial phase unwrapping (SPU) methods. TPU methods address phase unwrapping by acquiring multiple phase maps at different frequencies over time, with multi-frequency approaches [36] being commonly used to resolve phase surface discontinuities. SPU methods, which focus on phase unwrapping the phase in a single two-dimensional wrapped phase image, include path-following and minimum norm methods. The path-following approach recovers the continuous phase by defining integration paths, with common techniques, such as branch cut [37], quality-guided [38], and region growth [39]. The minimum norm method transforms phase unwrapping into a global optimization problem, aiming to minimize the difference between the phase gradient and the true phase gradient, with least squares being a typical representative technique.

Traditional phase unwrapping methods take into account the image features of the phase map and the algorithm’s stability, but they still encounter several challenges, including

- (1)

- Prolonged phase unwrapping time;

- (2)

- Limited robustness;

- (3)

- Poor generalization;

- (4)

- Low accuracy.

Deep learning approaches to phase unwrapping are typically categorized into two main types: regression-based methods and segmentation-based methods. Regression-based methods approach phase unwrapping as an image recovery problem, whereas segmentation-based methods treat it as an image segmentation issue.

To address the issue (1), Seonghwan Park et al. from South Korea introduced a deep learning model called “UnwrapGAN” in 2021 [40]. This model uses phase unwrapping as an image recovery task, effectively overcoming the challenges posed by phase discontinuities. Compared to traditional phase unwrapping methods, UnwrapGAN is able to perform phase unwrapping at twice the speed.

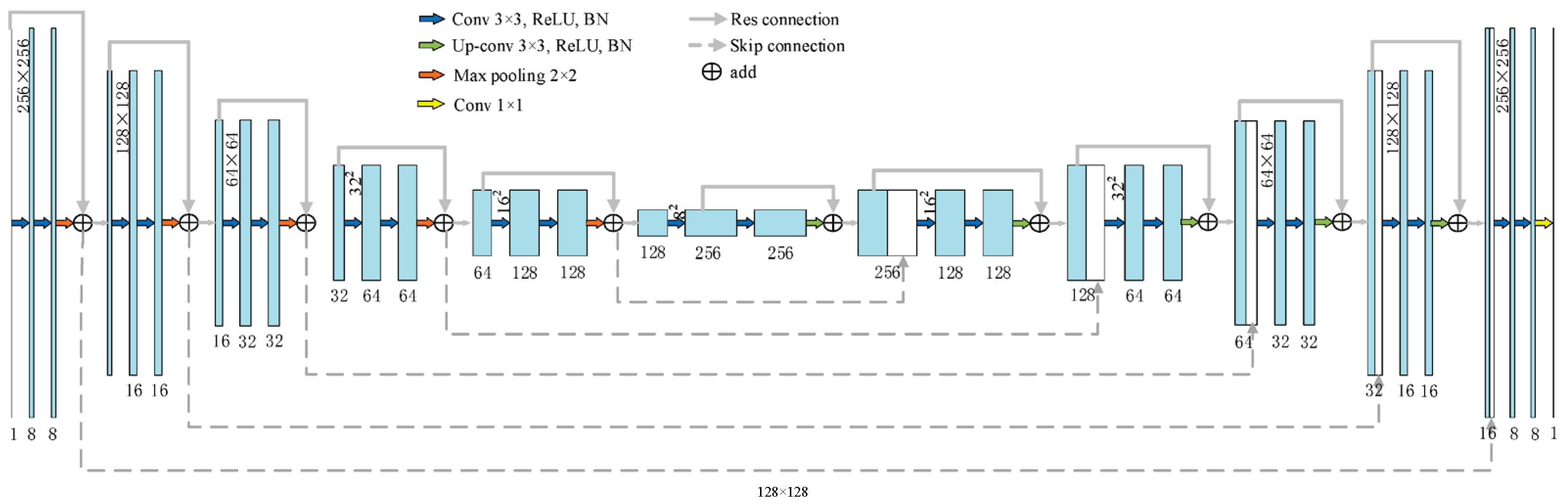

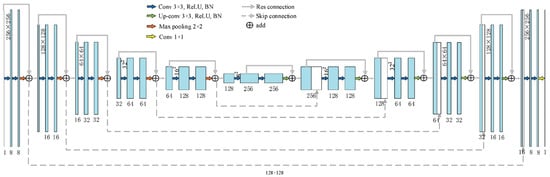

In 2024, Wang et al. from Hefei University of Technology introduced the Res-UNet network [41], as depicted in the detailed schematic in Figure 11. This network leverages the correlation between residual networks and U-Net networks. Compared to the “UnwrapGAN” model [40], the Res-UNet network achieves phase unwrapping in approximately 1 s, even for larger images. Additionally, in comparison to path-based algorithms, this network not only demonstrates superior noise suppression capabilities but also delivers better performance across varying image sizes.

Figure 11.

Detailed schematic of the neural network structure [41].

The Table 7 below presents an analysis and comparative summary of the mechanisms of deep learning and traditional methods for phase unwrapping, focusing on mitigating the phase unwrapping time problem.

Table 7.

Comparative analysis of traditional and deep learning methods in mitigating the phase unwrapping time problem.

The Table 8 below presents a comparative analysis of the impact of deep learning methods on reducing phase unwrapping time.

Table 8.

Comparative analysis of deep learning methods for reducing phase unwrapping time.

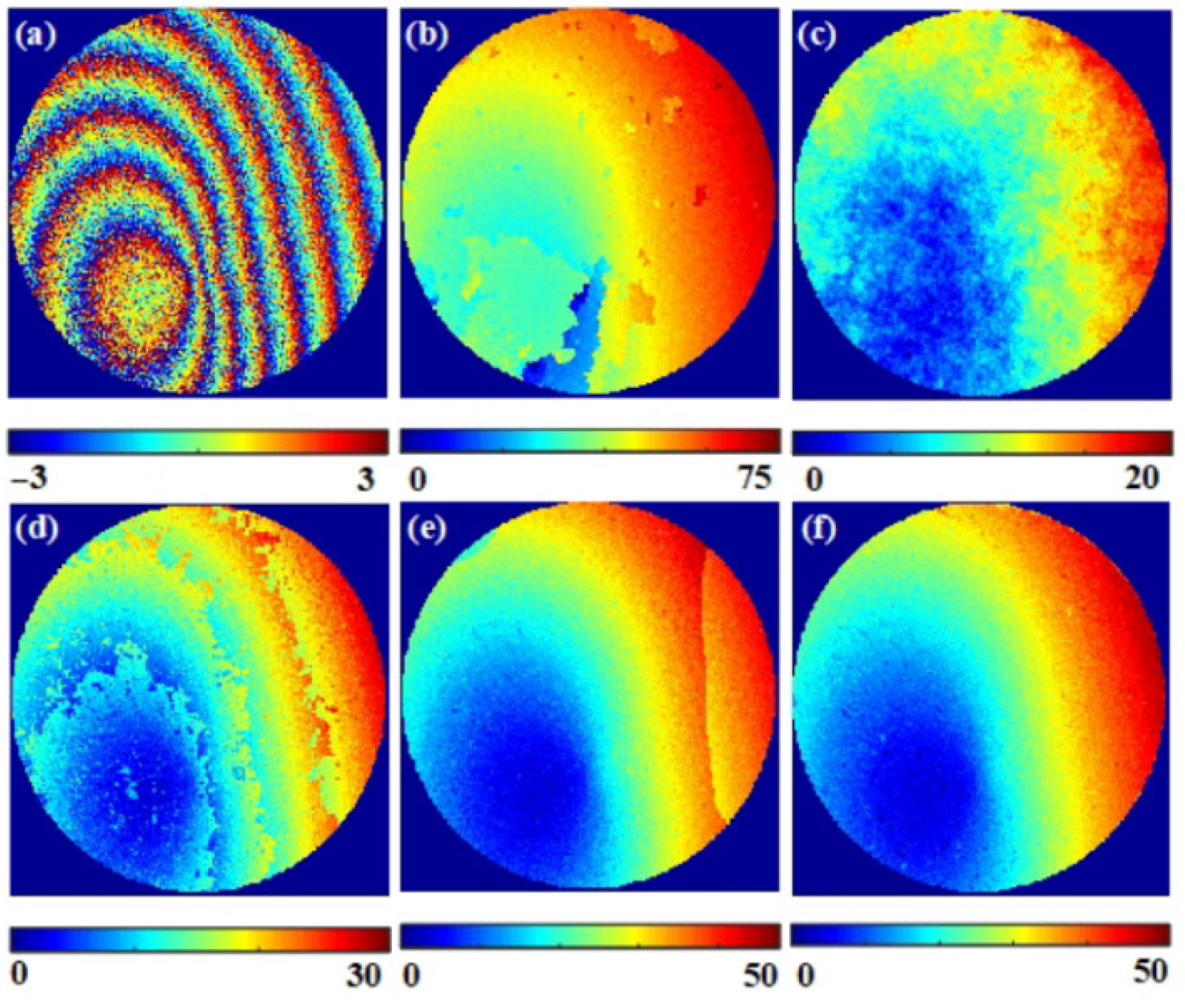

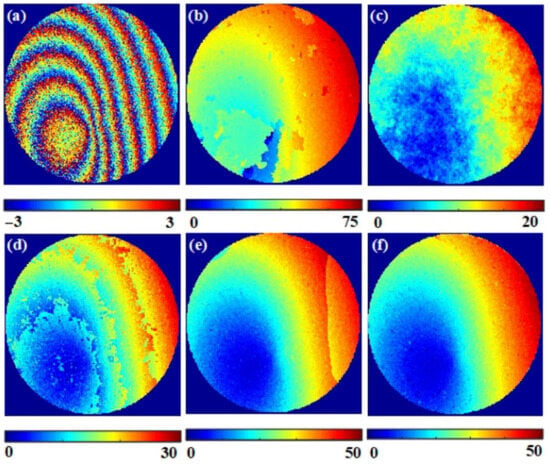

To address the issue (2), the following methods frame the problem as an image segmentation task. In 2019, Zhang et al. from Hangzhou Dianzi University introduced the DeepLabV3+ network [42], based on deep CNNs. Compared to conventional phase unwrapping techniques, this network delivers satisfactory phase unwrapping results, even in highly noisy conditions. Figure 12 in their study illustrates the phase unwrapping of real circular data of the methods in reference [42] and the traditional methods sorting by reliability following a noncontinuous path (SRFNP), transport of intensity equation (TIE), iterative transport of intensity equation (ITIE), and robust transport of intensity equation (RTIE) under significant noise.

Figure 12.

Phase unwrapping of real circular data under strong noise ((a–f) represent the wrapped phase map, SRFNP, TIE, ITIE, RTIE, and the unwrapped phase map generated by the method in reference [42], respectively).

In 2020, Spoorthi et al. from the Indian Institute of Technology introduced a new phase unwrapping learning framework called PhaseNet2.0 [43]. Unlike the previously proposed PhaseNet method [44], this framework incorporates a novel loss function (such as L1 and residual loss) and uses L1 loss to address class imbalance. Moreover, it eliminates the need for post-processing.

In 2024, Zhang et al. from Northwestern Polytechnical University, drawing inspiration from SegFormer [45], introduced a new phase unwrapping approach based on SFNet. This method outperforms traditional phase unwrapping approaches and the DeepLabV3+ network [42] in terms of noise resistance, accuracy, and generalization, especially in cases involving mixed noise and discontinuities.

In 2025, Awais et al. proposed the DenSFA-PU [46] network to address issues of poor robustness, error accumulation, and low computational efficiency in phase unwrapping under strong noise conditions.

The Table 9 below presents an analysis and comparative summary of the mechanisms of deep learning and traditional methods for phase unwrapping, focusing on addressing limited robustness.

Table 9.

Comparative mechanism analysis of deep learning methods addressing limited robustness in phase unwrapping.

The Table 10 below presents a comparative analysis of the impact of deep learning methods on improving robustness.

Table 10.

Comparative analysis of the effects of deep learning methods in addressing limited robustness in phase unwrapping.

To address the problem (3), the following networks treat the phase unwrapping algorithm as an image restoration task. In 2022, Zhao et al. from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China introduced the VDE-Net network [47], building upon the VUR-Net network [48]. This network incorporated a weighted skip-edge attention mechanism for the first time, and, compared to VUR-Net, the VDE-Net demonstrated improved performance in undersampled wrapped phase maps.

In 2023, Chen et al. from the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology developed the U2-Net network [49]. This model enhances generalization by incorporating deeper nested U-structures and residual modules, allowing it to maintain strong performance across various noise conditions and diverse datasets.

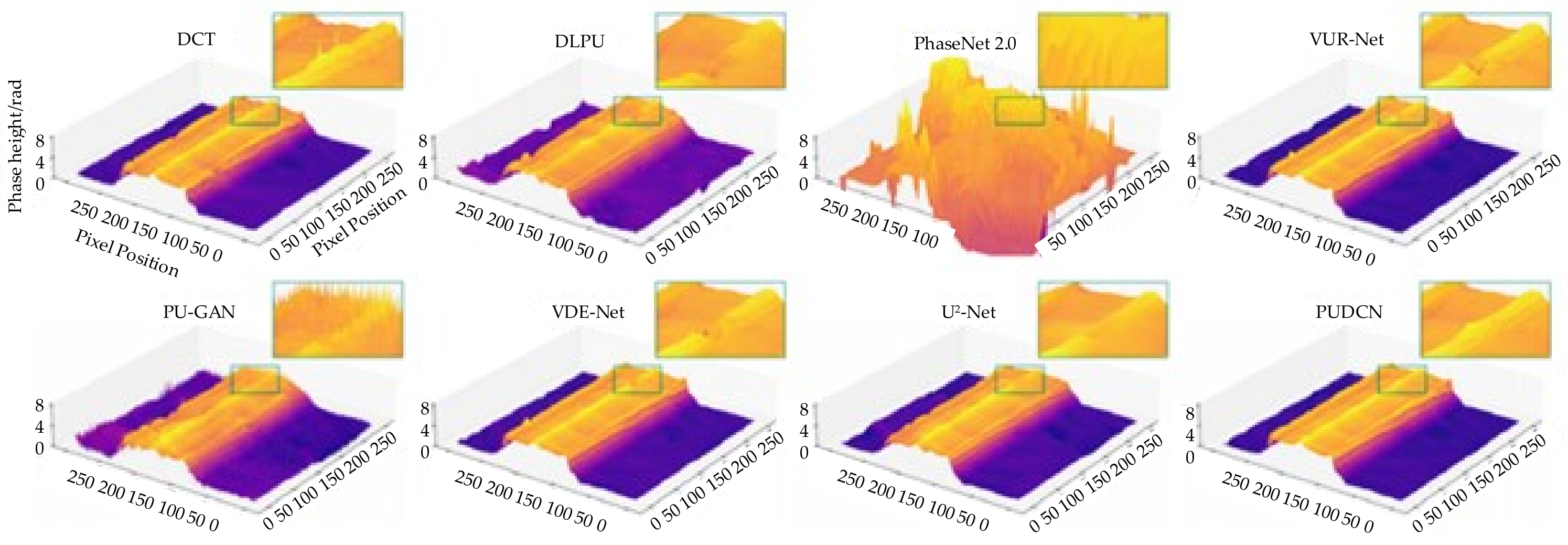

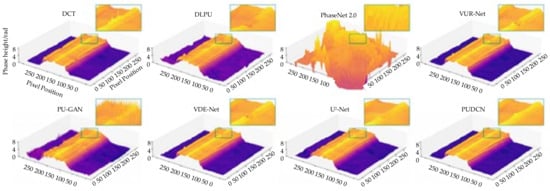

In 2024, Li et al. from Harbin Engineering University proposed the phase unwrapping deep convolutional network (PUDCN) for phase unwrapping in the presence of mixed noise and discontinuous regions [50]. The PUDCN was applied to phase unwrapping of optical fibers in interferometric measurements, demonstrating fewer fluctuations, outliers, and distortions, which indicates its robust generalization ability. Figure 13 presents a 3D visualization of the phase height of coaxial dual-waveguide fiber side projections, calculated using different methods.

Figure 13.

Three-dimensional visualization of the side projection phase height of coaxial dual-waveguide fibers calculated using different methods [50].

The Table 11 below presents an analysis and comparative summary of the mechanisms of deep learning and traditional methods for phase unwrapping, focusing on addressing poor generalization.

Table 11.

Mechanism comparison of deep learning methods addressing poor generalization in phase unwrapping.

The Table 12 below presents a comparative analysis of the impact of deep learning methods in addressing poor generalization.

Table 12.

Comparative analysis of the effects of deep learning methods in addressing poor generalization.

To address the problem (4), Li et al. from Guangxi University of Science and Technology proposed a deep learning-based center difference information filtering PU (DLCDIFPU) algorithm in 2023 [51]. This algorithm approaches the phase unwrapping problem as an image restoration task and introduces a novel, efficient, and robust filter (CDIF) combined with efficient local phase gradient estimation and a path-tracking strategy based on heap sorting. This approach improved the accuracy of phase unwrapping by approximately 15%.

In 2024, Zhao et al. from Guilin University of Electronic Technology introduced the C-HRNet network [52], which framed the phase unwrapping problem as an image segmentation challenge. By incorporating a high-resolution network and an object context representation module, the C-HRNet network significantly enhanced phase unwrapping accuracy. Notably, when compared to the DeeplabV3+ network, it exhibited lower root mean square error (RMSE) and higher PSNR.

The Table 13 below presents an analysis and comparative summary of the mechanisms of deep learning and traditional methods for phase unwrapping, focusing on addressing low accuracy.

Table 13.

Mechanism analysis of deep learning mechanisms addressing low accuracy in phase unwrapping.

The following Table 14 presents a comparative analysis of deep learning-based methods for enhancing accuracy.

where N represents the number of observations, denotes the actual value of the i-th observation, and indicates the predicted value of the i-th observation. X and Y signify the number of rows and columns of the unwrapped phase image, respectively. BEM(x, y) is the pixel value on the binary error map, where the pixel is 1 if the phase is correctly unwrapped, and 0 otherwise.

Table 14.

Comparative analysis of deep learning methods for addressing low accuracy in phase unwrapping.

In phase unpacking, the absolute error graph map serves as a critical metric for evaluating unwrapping accuracy. Equation (25) quantifies the error of understanding by computing the difference between the unwrapped and the ground truth phase images.

The Table 15 below presents a classification and comparative summary of deep learning and traditional methods for phase unwrapping.

Table 15.

Classification of phase unwrapping network dimensions.

4.3. Application of Deep Learning in Phase Distortion Compensation

Phase distortion can arise due to factors such as aberrations in the optical system, uneven illumination, tilt between the recording surface and the object, and the surface morphology of the object. These distortions can introduce unwanted low-frequency backgrounds, nonlinear errors, or high-frequency noise during the holographic reconstruction process, ultimately affecting the accuracy of the reconstructed image and the true optical characteristics of the sample.

Phase distortion compensation is a crucial process for eliminating these artifacts caused by imperfect systems or environments, correcting non-physical backgrounds, and restoring the true phase distribution of the target. This process improves the quality of holographic image reconstruction and enhances the accuracy of quantitative analysis. Traditional phase distortion compensation methods can generally be categorized into physical and numerical approaches. Physical methods typically involve electronically adjustable lenses, co-located DHM configurations, telecentric setups, and the use of identical objective lenses. Numerical methods rely on post-processing techniques and do not require additional holograms or optical components. These include fitting calculations, principal component analysis, spectral analysis, geometric transformations, and nonlinear optimization, typically implemented using traditional software.

While these traditional methods are grounded in mature physical and mathematical theories, they still face several limitations:

- (1)

- They require extensive preprocessing.

- (2)

- They are constrained by perturbation assumptions.

- (3)

- They often require manual intervention.

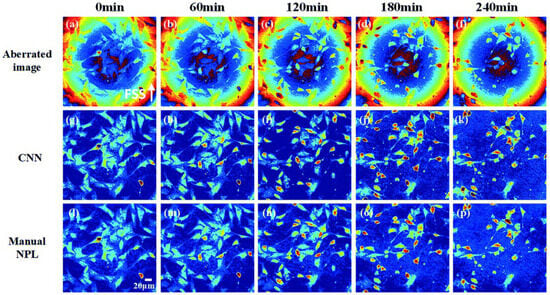

To address the issue (1), Xiao et al. from Beihang University proposed a CNN-based multi-variable regression distortion compensation method in 2021 [53]. This method predicts the optimal compensation coefficients and automatically compensates for phase distortions without needing to detect background areas or any physical parameters. Figure 14 compares the compensation results of this method with those of manual nonlinear programming-based phase compensation (NPL) methods across multiple time periods.

Figure 14.

Comparison of compensation results between the method in reference [53] and manual NPL over multiple time periods, where (a–d,f) represent distorted images at different time periods, (g–k) represent distorted images after distortion compensation by CNN at different time periods, and (l–p) represent distorted images after distortion compensation by Manual NPL at different time periods.

In 2023, Li et al. from Xi’an University of Technology introduced a digitally-driven phase distortion compensation network (PACUnet3+) [54]. This network directly generates a reference hologram from sample holograms, eliminating the need for any preprocessing techniques. PACUnet3+ outperforms the original Unet3+ network [55] in eliminating phase distortion and also surpasses traditional methods, such as phase aberration compensation (PAC) and fitting.

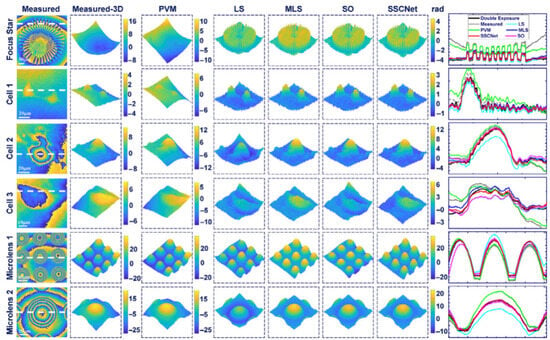

To address the issue (2), Tang et al. from Northwestern Polytechnical University introduced a self-supervised sparse constraint network (SSCNet) in 2023 [56]. The SSCNet combines sparse constraints with Zernike model enhancement and requires only a single measured phase for self-supervision. This network achieves high accuracy and stability in PAC, without the need for target masks or perturbation assumptions. When it comes to adaptive compensation for dynamic distortions, SSCNet outperforms the double exposure technique. Figure 15 compares the compensation results of SSCNet with those of various algorithms.

Figure 15.

Compensation effects of SSCNet and various algorithms [56].

The Table 16 below presents an analysis and comparative summary of the mechanisms of deep learning and traditional methods for phase distortion compensation, focusing on extensive preprocessing and perturbation assumption constraints.

Table 16.

Comparative analysis of deep learning mechanisms in extensive preprocessing and perturbation assumption constraints.

To address the issue (3), Thanh Nguyen et al. from the Catholic University of America proposed a fully automated technique in 2017 that combined deep learning-based CNNs and Zernike polynomial fitting (ZPF) [57]. This method’s advantage lies in its ability to automatically monitor the background region and compensate for higher-order aberrations, enhancing the accuracy of real-time measurements and enabling dynamic process monitoring.

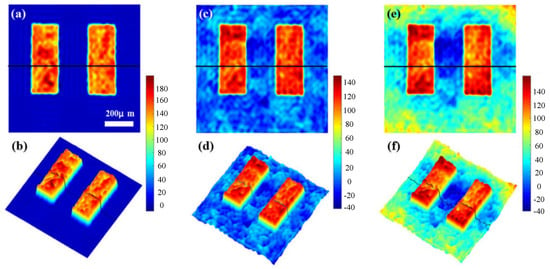

In 2021, MA et al. from Northeastern University [58] introduced a phase distortion compensation method for DHM based on a two-stage generative adversarial network (GAN). This method eliminates the need for a complex spectral centering process or prior knowledge, significantly simplifying the operational workflow while improving both precision and efficiency. It successfully automates the compensation process without requiring manual intervention. Figure 16 compares the distortion compensation results of this method with those of traditional approaches.

Figure 16.

(a) Result obtained by the proposed method; (b) 3D rendering of (a). (c) Result obtained by BS+ZPF; (d) 3D rendering of (c). (e) Result obtained by ZPF; (f) 3D rendering of (e) [58].

The Table 17 below presents an analysis and comparative summary of the mechanisms of deep learning and traditional methods for phase distortion compensation, focusing on addressing the manual intervention issue.

Table 17.

Comparative analysis of deep learning mechanisms addressing the manual intervention issue.

In summary, traditional phase distortion compensation methods offer advantages in terms of theoretical framework and algorithmic simplicity, while deep learning methods stand out for their adaptability and ability to manage complex relationships. However, there is still considerable potential for improving the effectiveness of phase distortion compensation using deep learning techniques in the future.

The Table 18 below presents a classification and comparative summary of deep learning and traditional methods for phase distortion compensation.

Table 18.

Classification table of phase distortion compensation network dimensions.

The Table 19 below presents a comparative analysis of deep learning-based phase distortion compensation methods.

Table 19.

Summary of deep learning-based methods for phase distortion compensation.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics for Phase Processing Results

In DHM, the quality of phase processing is essential, as it directly impacts the accuracy, fidelity, and applicability of the results. These results influence subsequent analyses and applications. Both qualitative and quantitative evaluations are commonly used to assess phase processing.

Qualitative evaluation generally focuses on three key factors: visual quality, detail preservation, and background smoothness. Quantitative evaluation involves numerical metrics to objectively assess the reconstruction from several perspectives, including phase accuracy, image quality, and noise suppression. Accuracy is often evaluated using metrics, such as the mean squared error (MSE) and MAE. Image quality is assessed with the PSNR and SSIM. Noise suppression is evaluated using the RMSE.

5. Summary and Outlook

Deep learning approaches in DHM have shown improvements in accuracy, processing speed, and generalization compared to traditional phase processing methods. However, research in this field is still in its early stages. Key areas for further exploration include the following:

- (1)

- Ultrafast 3D Holographic Reconstruction: Current 3D reconstruction in DHM relies on time-consuming iterative algorithms. Future work could focus on deep learning-based fast inversion algorithms, such as Bayesian–physical joint modeling [59] or a 3D reconstruction method based on unpaired data learning [60]. By training on a large dataset of paired holographic interference patterns and their 3D reconstructions, these models can be trained to learn the direct mapping. This pattern enables the rapid conversion of interference patterns into 3D reconstructions, significantly improving real-time imaging—particularly for capturing dynamic processes, such as cell movement.

- (2)

- High-Throughput Holographic Data Analysis: DHM generates vast amounts of data in high-throughput experiments (such as drug screening). Automating data analysis using deep learning pipelines, such as few-shot learning and transfer learning, could improve classification, segmentation, and feature extraction. In practice, the model can first be pre-trained on a large-scale general holographic dataset to learn a broad feature representation of the data. Subsequently, few-shot learning can be applied to quickly adapt the model to specific high-throughput experimental data, enabling accurate analysis and enhancing the efficiency and automation of these experiments.

- (3)

- Precise Quantification of Phase Analysis: In biomedical applications, accurate phase analysis is crucial for the non-destructive measurement of optical thickness and refractive index in cells and tissues. Deep learning could help develop more precise phase recovery algorithms. A CNN-based architecture can be tailored to effectively extract phase information from holograms. By introducing an attention mechanism, the network can prioritize key regions with significant phase features, enabling automatic extraction of quantitative data for complex biological analysis.

- (4)

- Multimodal Data Fusion: Combining DHM with other imaging techniques (e.g., electron or fluorescence microscopy) could significantly enhance the information gathered from images. Deep learning could integrate these modalities. A multimodal fusion network is specifically designed to extract features from each modality separately. These features are then combined through the fusion layer to reveal deeper structural and biological information, enhancing resolution, contrasts, and the diversity of biological markers in biomedical research.

Author Contributions

W.J.: Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation, Writing-review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. L.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Data curation, Investigation, Writing-original draft preparation. Y.B.: Methodology, Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (grant no. 2021JDJQ0027) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 61875166).

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying the results presented in this manuscript are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Wenbo Jiang gratefully acknowledges the support of the Sichuan Provincial Academic and Technical Leader Training Plan and the Overseas Training Plan of Xihua University (09/2014-09/2015, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goodman, J.W. Digital image formation from electronically detected holograms. Proc. SPIE-Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 1967, 10, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Qian, J.; Feng, S.; Yin, W.; Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Han, J.; Qian, K.; Chen, Q. Deep learning in optical metrology: A review. Light Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, W.; Qu, J. Ultralow laser power three-dimensional superresolution microscopy based on digitally enhanced STED. Biosensors 2022, 12, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K. Applications of digital holography in biomedical microscopy. J. Opt. Soc. Korea 2010, 14, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.C.; Xiong, Z.; McLeod, E. Clinical and biomedical applications of lensless holographic microscopy. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2400197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.J.; Yu, L.; Kim, M.K. Movies of cellular and sub-cellular motion by digital holographic microscopy. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2006, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ozcan, A. Lensless digital holographic microscopy and its applications in biomedicine and environmental monitoring. Methods 2017, 136, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivenson, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ozcan, A. Deep learning in holography and coherent imaging. Light Sci. Appl. 2019, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Song, L.; Wang, C.; Ren, Z.; Zhao, G.; Dou, J.; Di, J.; Barbastathis, G.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, J.; et al. On the use of deep learning for phase recovery. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, V.; Memmolo, P.; Leo, M.; Montresor, S.; Distante, C.; Paturzo, M.; Picart, P.; Javidi, B.; Ferraro, P. Strategies for reducing speckle noise in digital holography. Light Sci. Appl. 2018, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Huang, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Q.; Asundi, A. Temporal phase unwrapping algorithms for fringe projection profilometry: A comparative review. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2016, 85, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yan, W.; Li, R.; Weng, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, L.; Ye, T.; Qu, J. Aberration correction for improving the image quality in STED microscopy using the genetic algorithm. Nanophotonics 2018, 7, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Lam, E.Y. Deep learning for digital holography: A review. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 40572–40593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.K.; Depeursinge, C.; Popescu, G. Quantitative phase imaging in biomedicine. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K. Principles and techniques of digital holographic microscopy. J. Photonics Energy 2009, 1, 8005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; He, Z.; Cao, L. Double amplitude freedom Gerchberg-Saxton algorithm for generation of phase-only hologram with speckle suppression. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 120, 061103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, E.J.R.; Beck, A.; Eldar, Y.C.; Sabach, S. On Fienup methods for sparse phase retrieval. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2018, 66, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Guan, T.; Shen, Z.; Wang, X.; Hu, T.; Wang, D.; He, Y.; Xie, N. Fast phase retrieval in off-axis digital holographic microscopy through deep learning. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 19388–19405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahama, Y. Phase retrieval using hologram transformation with U-Net in digital holography. Opt. Contin. 2022, 1, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Dou, J.; Kemao, Q.; Di, J.; Zhao, J. Y-Net: A one-to-two deep learning framework for digital holographic reconstruction. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 4765–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, J.; Wang, Y. Deep-learning multiscale digital holographic intensity and phase reconstruction. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, C. An improved median filtering algorithm for image noise reduction. Phys. Procedia 2012, 25, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, S.; Ghosh, A.; Shankar, B.U. Fast mean filtering technique (FMFT). Pattern Recognit. 2007, 40, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, D.; Hatzinakos, D. Blind image deconvolution. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 1996, 13, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjatya, A. Block matching algorithms for motion estimation. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2004, 8, 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Dabov, K.; Foi, A.; Katkovnik, V.; Egiazarian, K. Image Denoising with Block-Matching and 3D Filtering. In Image Processing: Algorithms and Systems, Neural Networks, and Machine Learning, Proceedings of the Electronic Imaging 2006, 15–19 January 2006, San Jose, CA, USA; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 6064, pp. 354–365. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Benesty, J.; Huang, Y.; Doclo, S. New insights into the noise reduction Wiener filter. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2006, 14, 1218–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Kemao, Q.; Pan, B.; Asundi, A.K. Comparison of Fourier transform, windowed Fourier transform, and wavelet transform methods for phase extraction from a single fringe pattern in fringe projection profilometry. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2010, 48, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasenor, J.D.; Belzer, B.; Liao, J. Wavelet filter evaluation for image compression. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1995, 4, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Di, J. Coherent noise suppression in digital holographic microscopy based on label-free deep learning. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 880403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, B.; Yan, L.; Huang, L. Continuous phase denoising via deep learning based on Perlin noise similarity in digital holographic microscopy. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 8707–8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, T.; Choi, W.; Lee, B. A Lightweight Neural Network for Denoising Wrapped-Phase Images Generated with Full-Field Optical Interferometry. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Xia, H.-T.; Song, Q.; Zhang, M.; Guo, R.; Montresor, S.; Picart, P. Speckle denoising based on deep learning via a conditional generative adversarial network in digital holographic interferometry. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 20666–20683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Li, Q.; Song, Q.; Montresor, S.; Picart, P.; Xia, H. Convolutional and Fourier neural networks for speckle denoising of wrapped phase in digital holographic Interferometry. Opt. Commun. 2024, 550, 129955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.B.; Fang, Q.; Song, Q.H.; Montresor, S.; Picart, P.; Xia, H. Unsupervised speckle denoising in digital holographic interferometry based on 4-f optical simulation integrated cycle-consistent generative adversarial network. Appl. Opt. 2024, 63, 3557–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demer, D.A.; Soule, M.A.; Hewitt, R.P. A multiple-frequency method for potentially improving the accuracy and precision of in situ target strength measurements. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1999, 105, 2359–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenguer, J.-M.; Benavent, E.; Prins, C.; Prodhon, C.; Calvo, R.W. A branch-and-cut method for the capacitated location-routing problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2011, 38, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Su, X.; Asundi, A.; Kemao, Q. Quality-guided phase unwrapping technique: Comparison of quality maps and guiding strategies. Appl. Opt. 2011, 50, 6214–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, J. Improved region growing method for image segmentation of three-phase materials. Powder Technol. 2020, 368, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, Y.; Moon, I. Automated phase unwrapping in digital holography with deep learning. Biomed. Opt. Express 2021, 12, 7064–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cao, X.; Lan, M.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y. An Anti-noise-designed residual phase unwrapping neural network for digital speckle pattern interferometry. Optics 2024, 5, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Dixit, K.; Zhou, X.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, C. Rapid and robust two-dimensional phase unwrapping via deep learning. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 23173–23185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoorthi, G.E.; Gorthi, R.K.S.S.; Gorthi, S. PhaseNet 2.0: Phase unwrapping of noisy data based on deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 4862–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoorthi, G.E.; Gorthi, S.; Gorthi, R.K.S.S. PhaseNet: A deep convolutional neural network for two-dimensional phase unwrapping. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2018, 26, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Han, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, W.; Liu, M.; Lu, Q. Efficient and robust phase unwrapping method based on SFNet. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 15410–15432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Yoon, T.; Hwang, C.O.; Lee, B. DenSFA-PU: Learning to unwrap phase in severe noisy conditions. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 187, 112757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Du, X.; Hao, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. VDE-Net: A two-stage deep learning method for phase unwrapping. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 39794–39815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Wan, S.; Wan, Y.; Weng, J.; Liu, W.; Gong, Q. Direct and accurate phase unwrapping with deep neural network. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 7258–7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Fu, Y.; Zhuang, S. Two-dimensional phase unwrapping based on U2-Net in complex noise environment. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 29792–29812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Meng, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yuan, L. PUDCN: Two-dimensional phase unwrapping with a deformable convolutional network. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 27206–27220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiaying, L. Central difference information filtering phase unwrapping algorithm based on deep learning. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 163, 107484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yan, J.; Jin, D.; Ling, J. C-HRNet: High resolution network based on contexts for single-frame phase unwrapping. IEEE Photonics J. 2024, 16, 5100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Xin, L.; Cao, R.; Wu, X.; Tian, R.; Che, L.; Sun, L.; Ferraro, P.; Pan, F. Sensing morphogenesis of bone cells under microfluidic shear stress by holographic microscopy and automatic aberration compensation with deep learning. Lab A Chip 2021, 21, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, F.; Jin, P.; Zhang, H.; Feng, B.; Guo, R. Accurate phase aberration compensation with convolutional neural network PACUnet3+ in digital holographic microscopy. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 171, 107829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Wang, P.; Ni, C.; Hao, W. Cloud and snow detection of remote sensing images based on improved Unet3+. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Mao, S.; Ren, Z.; Di, J.; Zhao, J. Phase aberration compensation via a self-supervised sparse constraint network in digital holographic microscopy. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 168, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Bui, V.; Lam, V.; Raub, C.B.; Chang, L.-C.; Nehmetallah, G. AutAomatic phase aberration compensation for digital holographic microscopy based on deep learning background detection. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 15043–15057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Liu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, S. Quantitative phase imaging in digital holographic microscopy based on image inpainting using a two-stage generative adversarial network. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 24928–24946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Niu, H.; Su, W.; He, Z. Structured light 3D shape measurement for translucent media base on deep Bayesian inference. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; He, Z.; Su, W.; Huang, T.; Xie, S. Large depth range binary-focusing projection 3D shape reconstruction via unpaired data learning. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2024, 181, 108442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).