Abstract

The emergence of drug-resistant bacteria is considered a critical public health problem. The need to establish alternative approaches to countering resistant microorganisms is unquestionable in overcoming this problem. Among emerging alternatives, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) has become promising to control infectious diseases. aPDT is based on the activation of a photosensitizer (PS) by a particular wavelength of light followed by generation of the reactive oxygen. These interactions result in the production of reactive oxygen species, which are lethal to bacteria. Several types of research have shown that aPDT has been successfully studied in in vitro, in vivo, and randomized clinical trials (RCT). Considering the lack of reviews of RCTs studies with aPDT applied in bacteria in the literature, we performed a systematic review of aPDT randomized clinical trials for the treatment of bacteria-related diseases. According to the literature published from 2008 to 2022, the RCT study of aPDT was mostly performed for periodontal disease, followed by halitosis, dental infection, peri-implantitis, oral decontamination, and skin ulcers. A variety of PSs, light sources, and protocols were efficiently used, and the treatment did not cause any side effects for the individuals.

1. Introduction

Currently, one of the most important clinical challenges in the world is the increasing resistance of bacteria to antibiotics. According to recent reports about drug-resistant infections, the actual scenario shows a risk is being posed to the ability to treat common infections with any single kind of antibiotic, with antimicrobial resistance being one of the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity [1,2]. Humans have exposed microorganisms, specifically pathogenic microbial populations, to antimicrobial agents, such as antibiotics and antiseptics, to control infectious diseases. The overuse of these substances makes disease-causing microorganisms develop various resistance mechanisms to drugs commonly used to treat them, which is a severe worldwide threat to managing infectious diseases [3]. To overcome the resistance problem, the search for alternative approaches is necessary. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) has become a promising and potential treatment, since it is nontoxic, noninvasive, and has presented effective results against microorganisms, while not causing them to quickly develop resistance [4].

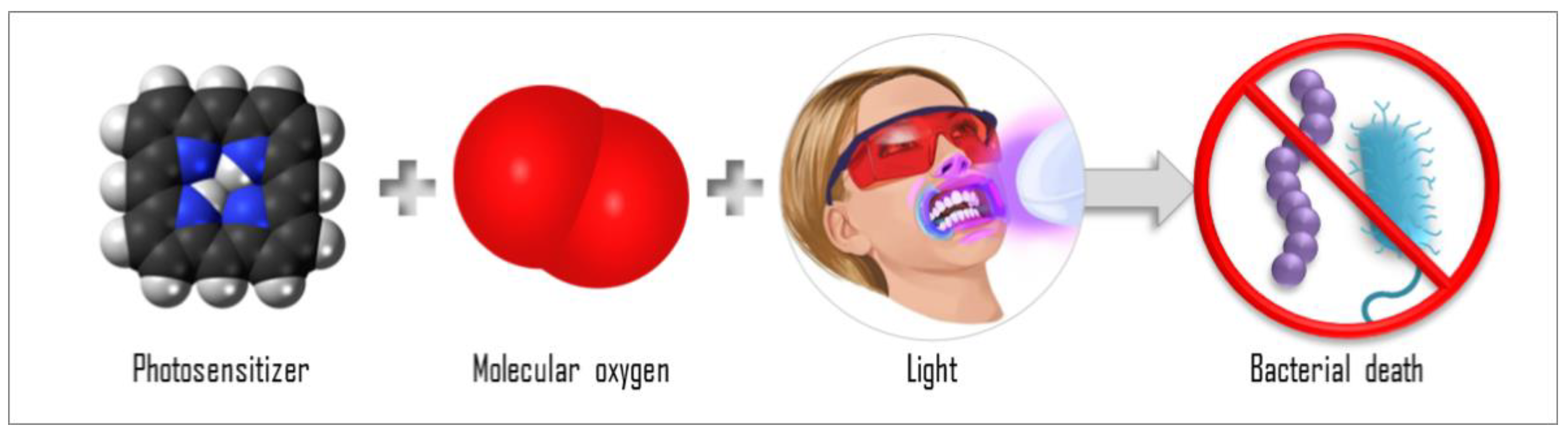

The mechanisms of aPDT are based on the interaction of the photosensitizer (PS) molecule with light in a compatible wavelength in the presence of molecular oxygen (Figure 1). When the PS molecule in its singlet ground state (S0) absorbs a photon (hν), it transitions to the singlet excited state (Sn). From Sn, the PS can release energy through fluorescence emission (f) or through internal conversion, releasing heat, then returning to the ground state, S0. The PS molecule may, from Sn, still undergo an intersystem crossing (ISC) to a triplet excited state (T1) with a longer lifetime. From T1, the PS may return to S0 after emitting phosphorescence (P) or after participating in reactions that lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS): type I reactions and type II reactions. In a type I reaction, when the PS is in the T1, it can transfer a proton or an electron to the substrate to form a radical anion or radical cation; these radicals may react with oxygen to produce ROS. In a type 2 reaction, the PS in the T1 can directly transfer energy to molecular oxygen (a triplet in the ground state), producing excited-state singlet oxygen (1O2). Both type 1 and 2 reactions occur simultaneously, but depending on the chemical structure of the PS, one of the reactions will be preferential. The efficiency of the aPDT is often related to the 1O2 quantum yield of the PS [5,6,7,8]. The photoproducts species are responsible for inducing the death of the target cell. Then, aPDT represents a multi-target damaging process, since the reactive oxygen species generated can interact and damage all structures that are close to them. For this reason, the effectiveness of the aPDT is also related to the PS localization and uptake, where the oxidative process will occur [9,10]. Moreover, the ability of the ROS to damage a nonspecific site means that aPDT is unlikely to induce resistance in the microorganisms, and this characteristic is an advantage of aPDT over antibiotics. Antibiotics, regardless of the class, bind to and act on a specific target, to that the bacteria is more likely to develop resistance to them.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) components: interaction of PS, molecular oxygen, and light, causing bacterial death.

Photodynamic action has been applied to non-melanoma skin lesions with well-established protocols and is strongly recommended by the American and European academies of dermatology [11,12,13]. Moreover, many other areas have promisingly benefited from this technique with marked improvement in human-health-concerning infections; however, these do not have defined, validated, effective, and secure protocols.

For example, some aPDT applications, such as the control of disease vectors, are also a great gain that photodynamics can offer. Through the use of appropriate PSs, it is possible to place breeding sites for vectors of the main diseases, such as dengue, etc., in suitable forms that allow the larvae to absorb the substance. With this and with the help of sunlight, the elimination of these larvae can reach 90%, without any aggression to the environment [14,15]. Decontamination of blood banks is also a source of infection for humans [16] and photodynamic with riboflavin and UVA light allows a considerable decrease in the viral and bacterial load of blood bags, thus decreasing the chances of contamination of receptors [17].

Additionally, many infectious diseases are caused by contamination in food [18]. In the case of raw foods (meats, grains, vegetables, and fruits), the number of contaminants that remain in the food when it reaches the consumer’s hands are large. The action of aPDT has been shown to be adequate for the preservation and elimination of infectious factors in food. Finally, water-borne diseases are also a global burden that is estimated to cause several million deaths and innumerable cases of sickness every year. The application of photodynamic processes has been exploited to address the decontamination of waters, where sunlight-mediated aPDT can eliminate pathogens present in municipal and other water supplies [19]. These examples are some cases on the subject, which demonstrate that photodynamic inhibition can go far beyond human health.

The antimicrobial potential of PDT has also been widely and successfully applied for the management of bacterial infectious diseases, such as for the oral decontamination of orthodontic patients [20,21]; for the inactivation of Streptococcus mutans biofilm [22,23] and Staphylococcus aureus biofilm in in vitro and in vivo studies [24]; in the treatment of pharyngotonsillitis [25,26]; against bacteria that cause pulmonary diseases [27,28,29]; in the decontamination of blood [16,30,31]; and in cooperative and competitive aPDT effects [32]. Some studies have focused on the development of new compounds for the enhancement of aPDT [33]. In this context, researchers have synthesized nanoparticle and dye diffusion in bacterial biofilms for aPDT applications [34], such as the use of superhydrophobic sensitizer techniques in the treatment of periodontitis [35].

The natural evolution of these in vitro and in vivo aPDT findings is to translate them to clinical trials aiming to define and validate effective and secure protocols. There are several types of clinical studies, such as randomized controlled trials (RCT), cohort studies, case–control studies, case series, case reports, and opinion reports. Considering the hierarchy of evidence parameters among them, RCT can be considered the gold standard of clinical trials, providing the most reliable evidence of the effectiveness of interventions. RCTs are designed to have the participants randomly assigned to one of two or more clinical interventions which minimize the risk of confounding factors influencing the results [36].

Considering the lack in the literature of reviews reuniting RCTs studies with aPDT applied in bacteria, we performed a systematic review aiming at aPDT randomized clinical trials to treat bacteria-related diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

The present systematic review searched aPDT randomized clinical trials for the treatment of bacteria-related diseases. The studies were collected from The Web of Science database, using the keywords “Photodynamic”, “bacteria”, and “randomized controlled”, from 2008 to 2022.

3. Results and Discussion

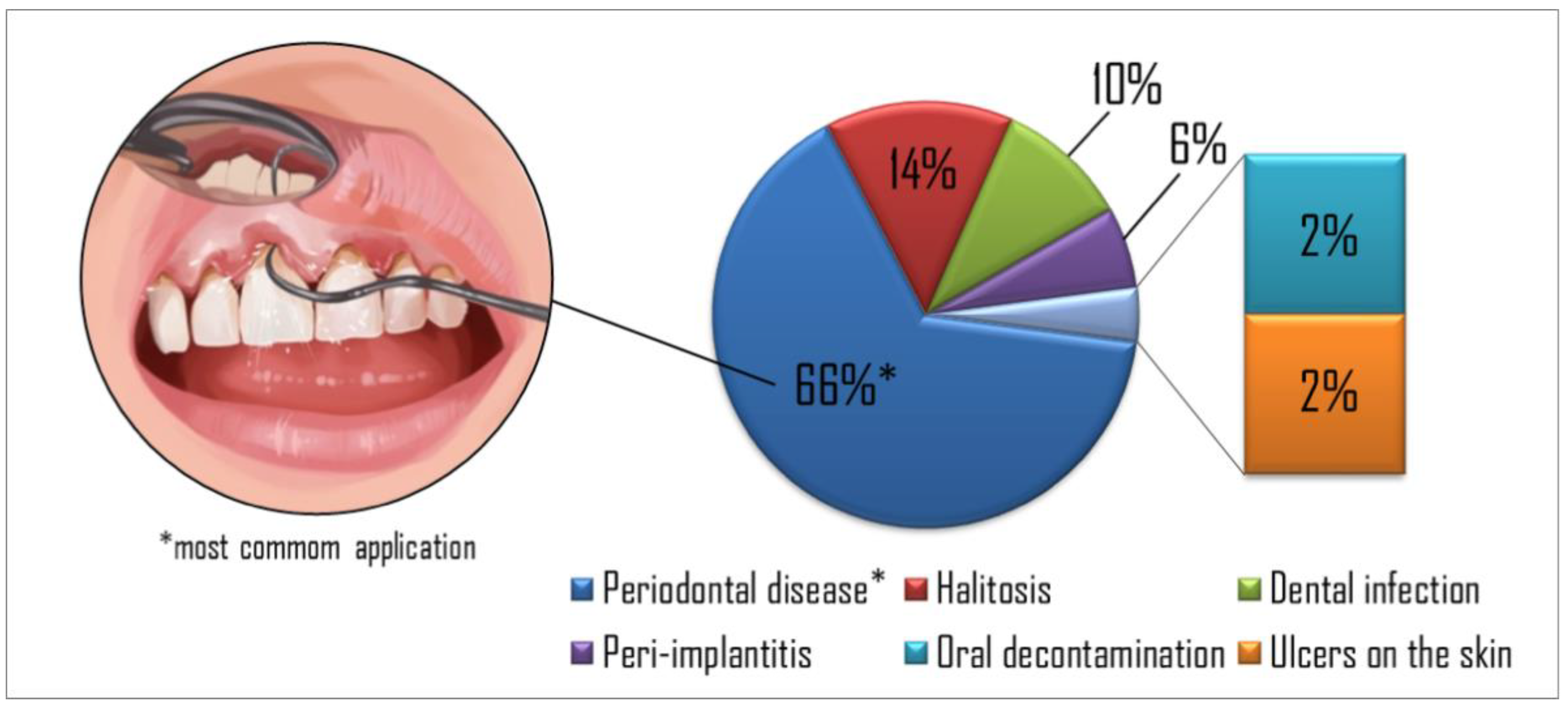

Figure 2 summarizes the percentage of each aPDT application in the studies evaluated. Periodontal disease was the most common application explored in the studies (65%), followed by halitosis (14%), dental infection (10%), peri-implantitis (6%), oral decontamination (2%), and skin ulcers (2%), respectively. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 show the studies’ details organized by diseases found in the present search.

Figure 2.

The percentage of targets in the papers reviewed showed periodontal disease as the most common application found in the studies, followed by halitosis, dental infection, peri-implantitis, oral decontamination, and skin ulcers, respectively.

Table 1.

Randomized clinical trials that evaluated aPDT for the treatment of periodontal disease. SRP—scaling and root planning.

Table 2.

Randomized clinical trials that evaluated aPDT for the treatment of halitosis.

Table 3.

Randomized clinical trials that evaluated aPDT for the treatment of peri-implantitis.

Table 4.

Randomized clinical trials that evaluated aPDT for the treatment of dental infections.

Table 5.

Randomized clinical trials that evaluated aPDT for oral decontamination.

Table 6.

Randomized clinical trials that evaluated aPDT for the treatment of ulcers on the skin.

About 65% of the studies (32/49) we reviewed were related to periodontal disease and they are presented in Table 1. Periodontal disease affects the gingiva, the supporting connective tissue, and the alveolar bone, which anchor the teeth in the jaws. Gingivitis is the mildest form of periodontal disease and is caused by bacterial biofilm (dental plaque) that accumulates on teeth surface adjacent to the gingiva (gums). Periodontitis causes loss of connective tissue and bone support, being a significant cause of tooth loss in adults. In addition to pathogenic microorganisms in the biofilm, genetic and environmental factors, especially tobacco use, contribute to the cause of these diseases [86,87]. The treatment of disease is directed at slowing the progression of the disease process, with mechanical removal of the bacteria. The treatment regime depends on the severity of the disease, the presence or absence of periodontal pockets, and the extent of the loss of alveolar bone; the more advanced the destruction, the more mechanical intervention is necessary [86]. Most of the studies presented in Table 1 compare the association of aPDT with conventional methods: ultrasonic debridement and/or scaling and root planning (SRP).

Among the aPDT protocols used, phenothiazine chlorine, methylene blue, toluidine blue, and indocyanine green (ICG) were adopted as PSs with a maximum incubation period of 5 min. The regions treated with ICG were irradiated at 810 nm, while the irradiations were performed at ranges between 628 and 680 nm to use the other PSs. It is also possible to verify the irradiation protocols, with irradiance varying between 2 and 100 mW/cm2 and fluences between 20 and 320 J/cm2. The trials presented follow-up reviews of 21 days–12 months.

Several studies point out that there is no significant difference between the conventional procedure groups without or with the association of aPDT. In contrast, several other studies observed significant clinical differences as a reduction in bleeding scores, gingival inflammation, and some of the critical periodontal pathogens. All protocols that used ICG as PSs in association with conventional treatment observed improvement in the clinical aspect, concluding that aPDT is a promising adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal therapy [51,65,68]. A single study was performed comparing conventional ultrasonic and aPDT alone and both therapies resulted in the same clinical effect; however, aPDT was less harmful to teeth than ultrasonic therapy [41].

Moreover, aPDT has been applied to treat other infectious diseases, such as halitosis (Table 2), peri-implantitis (Table 3), dental infection (Table 4), oral decontamination (Table 5), and ulcers on the skin (Table 6). Concerning halitosis, it is an oral condition that is characterized by unpleasant odors emanating from the oral cavity caused by deep carious lesions, peri-implant disease, periodontal disease, oral infections, mucosal ulcerations, pericoronitis, and impacted food. [88] In order to develop a safe and effective protocol to treat halitosis, authors from Brazil and Saudi Arabia evaluated (2014–2021) different clinical photodynamic protocols/conditions for treating the tongue, e.g., light parameters (395–660 nm, 36–318 J/cm2), PS type, and concentration and with different follow-up periods (7 days–3 months). These studies reported the effectiveness (reduction in oral pathogens) of aPDT against halitosis. Methylene blue has been applied as a PS to treat halitosis due to its low toxicity and high efficiency. Additionally, the authors concluded that aPDT is a useful and efficient option for treating halitosis without mechanical aggression of the lingual papillae.

Furthermore, aPDT was evaluated in treatment of peri-implantitis (Table 3). This is a pathological health condition in tissues (around dental implants), characterized by an inflammation process in the peri-implant tissue and loss of supporting bone [89]. According to our knowledge, there are three randomized controlled clinical studies concerning the application of aPDT to treat peri-implantitis. In these studies, authors reported the use of aPDT as an adjunctive option or as the primary treatment option to treat initial peri-implantitis, decontamination of the implant surface, and peri-implant diseases. Only two different PSs were applied to treat peri-implantitis, namely phenothiazine chloride and Fotosan. The authors observed a significant reduction in bleeding on probing compared with chlorhexidine (control group) and substantial decontamination of implant surfaces. Moreover, the authors observed an effective reduction in mucosal inflammation process.

Besides periodontal disease, halitosis, and peri-implantitis, there are a set of randomized controlled clinical studies reporting the use of aPDT against dental infections (Table 4) and oral decontamination (Table 5). The authors used different parameters, PSs (toluidine blue, methylene blue, and curcumin), and control groups (e.g., antibiotics, calcium hydroxide therapy, and others) to compare the results obtained. In addition, the authors reported that aPDT can disaggregate oral plaque and reduce the pathogenic microorganisms load present in the oral cavity. In this regard, aPDT was also applied to treat ulcers (chronic diabetic foot) and the authors demonstrated a significant photoinactivation of bacteria (Table 6).

4. Conclusions

Finally, it is possible to conclude that, from 2008 to 2022, aPDT was studied mainly for dentistry applications and was demonstrated to have promising clinical results. A variety of PSs, light sources, and protocols were efficiently used, and the treatment did not cause any side effects for the individuals. However, it is important to emphasize that the lack of standardization in the studies hinders the comparison among them and hinders the translation of preclinical results to clinical studies, which can lead to the failure of the treatment. Future studies should consider performing randomized clinical trials evaluating other infectious diseases, since this treatment has demonstrated antimicrobial effectiveness in in vitro, in vivo, and clinical reports; however, there are few RCT studies that could help the feasibility of this therapy for the management of other infectious diseases. Besides that, the constant emergence of resistant bacteria to the conventional antibiotics and the improbably improbable development of resistance to aPDT, turn photodynamic therapy into a powerful alternative antimicrobial method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A., M.D.S., M.B.R., K.C.B., L.D.D., T.Q.C. and V.S.B.; methodology, F.A. and L.D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A., M.D.S., M.B.R., K.C.B., L.D.D. and T.Q.C.; writing—review and editing, F.A., M.D.S., M.B.R., K.C.B., L.D.D., T.Q.C. and V.S.B.; supervision, V.S.B.; project administration, F.A.; funding acquisition, V.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP/CEPOF), Proc. Nº 13/07276-1. Blanco K.C. thanks FAPESP for Post-doc grant 2019/12694-3 and 2021/09952-0. L.D. Dias thanks FAPESP for Post-doc grant 2019/13569-8. F.A. thanks FAPESP for Post-doc grant 2021/01324-0.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the free data base used to create part of the Figure 1 and Figure 2. The websites are: https://www.authoritydental.org/, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Porphyrin-3D-spacefill.png, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oxygen_molecule.svg, accessed on 2 April 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; Government of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2018.

- Kashef, N.; Hamblin, M.R. Can microbial cells develop resistance to oxidative stress in antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation? Drug Resist. Updat. 2017, 31, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youf, R.; Müller, M.; Balasini, A.; Thétiot, F.; Müller, M.; Hascoët, A.; Jonas, U.; Schönherr, H.; Lemercier, G.; Montier, T.; et al. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy: Latest Developments with a Focus on Combinatory Strategies. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieplik, F.; Deng, D.; Crielaard, W.; Buchalla, W.; Hellwig, E.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Maisch, T. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy-what we know and what we don’t. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klausen, M.; Ucuncu, M.; Bradley, M. Design of Photosensitizing Agents for Targeted Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandna, S.; Thakur, N.S.; Kaur, R.; Bhaumik, J. Lignin–Bimetallic Nanoconjugate Doped pH-Responsive Hydrogels for Laser-Assisted Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 3216–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, J.M. Reactive Oxygen Species in Photodynamic Therapy: Mechanisms of Their Generation and Potentiation. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 343–394. [Google Scholar]

- Jori, G.; Fabris, C.; Soncin, M.; Ferro, S.; Coppellotti, O.; Dei, D.; Fantetti, L.; Chiti, G.; Roncucci, G. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of microbial infections: Basic principles and perspective applications. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006, 38, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacellar, I.O.L.; Oliveira, M.C.; Dantas, L.S.; Costa, E.B.; Junqueira, H.C.; Martins, W.K.; Durantini, A.M.; Cosa, G.; Di Mascio, P.; Wainwright, M.; et al. Photosensitized Membrane Permeabilization Requires Contact-Dependent Reactions between Photosensitizer and Lipids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9606–9615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.A.; Szeimies, R.M.; Basset-Séguin, N.; Calzavara-Pinton, P.G.; Gilaberte, Y.; Hædersdal, M.; Hofbauer, G.F.L.; Hunger, R.E.; Karrer, S.; Piaserico, S.; et al. European Dermatology Forum guidelines on topical photodynamic therapy 2019 Part 2: Emerging indications–field cancerization, photorejuvenation and inflammatory/infective dermatoses. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.A.; Szeimies, R.M.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Calzavara-Pinton, P.; Gilaberte, Y.; Hædersdal, M.; Hofbauer, G.F.L.; Hunger, R.E.; Karrer, S.; Piaserico, S.; et al. European Dermatology Forum guidelines on topical photodynamic therapy 2019 Part 1: Treatment delivery and established indications–actinic keratoses, Bowen’s disease and basal cell carcinomas. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 2225–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braathen, L.R.; Szeimies, R.-M.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Bissonnette, R.; Foley, P.; Pariser, D.; Roelandts, R.; Wennberg, A.-M.; Morton, C.A. Guidelines on the use of photodynamic therapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: An international consensus. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 56, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzacappo, N.F.; Souza, L.M.; Inada, N.M.; Dias, L.D.; Garbuio, M.; Venturini, F.P.; Corrêa, T.Q.; Moura, L.; Blanco, K.C.; de Oliveira, K.T.; et al. Curcumin/d-mannitol as photolarvicide: Induced delay in larval development time, changes in sex ratio and reduced longevity of Aedes aegypti. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2530–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, L.M.; Inada, N.M.; Venturini, F.P.; Carmona-Vargas, C.C.; Pratavieira, S.; de Oliveira, K.T.; Kurachi, C.; Bagnato, V.S. Photolarvicidal effect of curcuminoids from Curcuma longa Linn. against Aedes aegypti larvae. J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 2019, 22, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, T.Q.; Blanco, K.C.; Soares, J.M.; Inada, N.M.; Kurachi, C.; Golim, M.D.A.; Deffune, E.; Bagnato, V.S. Photodynamic inactivation for in vitro decontamination of Staphylococcus aureus in whole blood. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 28, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Li, C.; Wang, D. A novel ultraviolet illumination used in riboflavin photochemical method to inactivate drug-resistant bacteria in blood components. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020, 204, 111782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, T.Q.; Blanco, K.C.; Garcia, E.B.; Perez, S.M.L.; Chianfrone, D.J.; Morais, V.S.; Bagnato, V.S. Effects of ultraviolet light and curcumin-mediated photodynamic inactivation on microbiological food safety: A study in meat and fruit. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 30, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jori, G.; Magaraggia, M.; Fabris, C.; Soncin, M.; Camerin, M.; Tallandini, L.; Coppellotti, O.; Guidolin, L. Photodynamic Inactivation of Microbial Pathogens: Disinfection of Water and Prevention of Water-Borne Diseases. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2011, 30, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panhóca, V.H.; Luis Esteban Florez, F.; Quatrini Corrêa, T.; Paolillo, F.R.; Oliveira de Souza, C.W.; Bagnato, V.S. Oral decontamination of orthodontic patients using photodynamic therapy mediated by blue-light irradiation and curcumin associated with sodium dodecyl sulfate. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammery, D.; Michelogiannakis, D.; Ahmed, Z.U.; Ahmed, H.B.; Rossouw, P.E.; Romanos, G.E.; Javed, F. Scope of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in Orthodontics and related research: A review. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 25, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhóca, V.H.; Carreira Geralde, M.; Corrêa, T.Q.; Carvalho, M.T.; Wesley, C.; Souza, O.; Bagnato, V.S. Enhancement of the Photodynamic Therapy Effect on Streptococcus Mutans Biofilm. J. Phys. Sci. Appl. 2014, 4, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, M.; Deng, D.M.; Wu, Y.; de Oliveira, K.T.; Bagnato, V.S.; Crielaard, W.; de Souza Rastelli, A.N. Photodynamic inactivation mediated by methylene blue or chlorin e6 against Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 31, 101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.P.; Alves, F.; Stringasci, M.D.; Buzzá, H.H.; Ciol, H.; Inada, N.M.; Bagnato, V.S. One-Pot Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Carbon Dots and in vivo and in vitro Antimicrobial Photodynamic Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 662149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, K.C.; Inada, N.M.; Carbinatto, F.M.; Giusti, A.L.; Bagnato, V.S. Treatment of recurrent pharyngotonsillitis by photodynamic therapy. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 18, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, J.M.; Inada, N.M.; Bagnato, V.S.; Blanco, K.C. Evolution of surviving Streptoccocus pyogenes from pharyngotonsillitis patients submit to multiple cycles of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020, 210, 111985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geralde, M.C.; Leite, I.S.; Inada, N.M.; Salina, A.C.G.; Medeiros, A.I.; Kuebler, W.M.; Kurachi, C.; Bagnato, V.S. Pneumonia treatment by photodynamic therapy with extracorporeal illumination—An experimental model. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, I.S.; Geralde, M.C.; Salina, A.C.G.; Medeiros, A.I.; Dovigo, L.N.; Bagnato, V.S.; Inada, N.M. Near–infrared photodynamic inactivation of S. pneumoniae and its interaction with RAW 264.7 macrophages. J. Biophotonics 2018, 11, e201600283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassab, G.; Geralde, M.C.; Inada, N.M.; Achiles, A.E.; Guerra, V.G.; Bagnato, V.S. Nebulization as a tool for photosensitizer delivery to the respiratory tract. J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.; Gomes, A.T.; Freitas, A.; Faustino, M.A.; Neves, M.G.; Almeida, A. Photodynamic inactivation of candida albicans in blood plasma and whole blood. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spesia, M.B.; Rovera, M.; Durantini, E.N. Photodynamic inactivation of Escherichia coli and Streptococcus mitis by cationic zinc (II) phthalocyanines in media with blood derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 2198–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.D.; Correa, T.Q.; Bagnato, V.S. Cooperative and competitive antimicrobial photodynamic effects induced by a combination of methylene blue and curcumin. Laser Phys. Lett. 2021, 18, 075601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratavieira, S.; Uliana, M.P.; dos Santos Lopes, N.S.; Donatoni, M.C.; Linares, D.R.; de Freitas Anibal, F.; de Oliveira, K.T.; Kurachi, C.; de Souza, C.W.O. Photodynamic therapy with a new bacteriochlorin derivative: Characterization and in vitro studies. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 34, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, C.C.; Ashraf, S.; Alburquerque, J.Q.; Souza Rastelli, A.N.; Hasan, T.; Lyons, A.M.; Greer, A. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Inactivation Using Topical and Superhydrophobic Sensitizer Techniques: A Perspective from Diffusion in Biofilms. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushalkar, S.; Ghosh, G.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ghogare, A.A.; Atem, C.; Greer, A.; Saxena, D.; Lyons, A.M. Superhydrophobic Photosensitizers: Airborne 1 O 2 Killing of an in Vitro Oral Biofilm at the Plastron Interface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 25819–25829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akobeng, A.K. Understanding randomised controlled trials. Arch. Dis. Child. 2005, 90, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Christodoulides, N.; Nikolidakis, D.; Chondros, P.; Becker, J.; Schwarz, F.; Rössler, R.; Sculean, A. Photodynamic Therapy as an Adjunct to Nonsurgical Periodontal Treatment: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 1638–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondros, P.; Nikolidakis, D.; Christodoulides, N.; Rössler, R.; Gutknecht, N.; Sculean, A. Photodynamic therapy as adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal treatment in patients on periodontal maintenance: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2009, 24, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulic, M.; Leiggener Görög, I.; Salvi, G.E.; Ramseier, C.A.; Mattheos, N.; Lang, N.P. One-year outcomes of repeated adjunctive photodynamic therapy during periodontal maintenance: A proof-of-principle randomized-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Huang, Y.Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Photodynamic therapy for localized infections-State of the art. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2009, 6, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rühling, A.; Fanghänel, J.; Houshmand, M.; Kuhr, A.; Meisel, P.; Schwahn, C.; Kocher, T. Photodynamic therapy of persistent pockets in maintenance patients—A clinical study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2010, 14, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoro, L.H.; Silva, S.P.; Pires, J.R.; Soares, G.H.G.; Pontes, A.E.F.; Zuza, E.P.; Spolidório, D.M.P.; de Toledo, B.E.C.; Garcia, V.G. Clinical and microbiological effects of photodynamic therapy associated with nonsurgical periodontal treatment. A 6-month follow-up. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balata, M.L.; Andrade, L.P.D.; Santos, D.B.N.; Cavalcanti, A.N.; Tunes, U.D.R.; Ribeiro, E.D.P.; Bittencourt, S. Photodynamic therapy associated with full-mouth ultrasonic debridement in the treatment of severe chronic periodontitis: A randomized-controlled clinical trial. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2013, 21, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongardini, C.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Pilloni, A. Light-activated disinfection using a light-emitting diode lamp in the red spectrum: Clinical and microbiological short-term findings on periodontitis patients in maintenance. A randomized controlled split-mouth clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2014, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, G.D.O.; Novaes, A.B.; Souza, S.L.S.; Taba, M.; Palioto, D.B.; Grisi, M.F.M. Additional effects of aPDT on nonsurgical periodontal treatment with doxycycline in type II diabetes: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2014, 29, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, G.U.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, S.J.; Pang, E.K. Effects of adjunctive daily phototherapy on chronic periodontitis: A randomized single-blind controlled trial. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2014, 44, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Betsy, J.; Prasanth, C.S.; Baiju, K.V.; Prasanthila, J.; Subhash, N. Efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the management of chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, V.F.; Andrade, P.V.C.; Rodrigues, M.F.; Hirata, M.H.; Hirata, R.D.C.; Pannuti, C.M.; De Micheli, G.; Conde, M.C. Antimicrobial photodynamic effect to treat residual pockets in periodontal patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.L.; Novaes, A.B.; Grisi, M.F.; Taba, M.; Souza, S.L.; Palioto, D.B.; de Oliveira, P.G.; Casati, M.Z.; Casarin, R.C.; Messora, M.R. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy as an Adjunct to Nonsurgical Treatment of Aggressive Periodontitis: A Split-Mouth Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birang, R.; Shahaboui, M.; Kiani, S.; Shadmehr, E.; Naghsh, N. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal treatment combined with diode laser or photodynamic therapy on chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled split-mouth clinical trial. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 6, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srikanth, K.; Chandra, R.V.; Reddy, A.A.; Reddy, B.H.; Reddy, C.; Naveen, A. Effect of a single session of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy using indocyanine green in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Quintessence Int. 2015, 46, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelli, M.; Formigli, L.; Lorenzini, L.; Bani, D. Efficacy of Combined Photoablative-Photodynamic Diode Laser Therapy Adjunctive to Scaling and Root Planing in Periodontitis: Randomized Split-Mouth Trial with 4-Year Follow-Up. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2015, 33, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulikkotil, S.J.; Toh, C.G.; Mohandas, K.; Leong, K.V.G. Effect of photodynamic therapy adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients: A randomized clinical trial. Aust. Dent. J. 2016, 61, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castro dos Santos, N.C.; Andere, N.M.R.B.; Araujo, C.F.; de Marco, A.C.; dos Santos, L.M.; Jardini, M.A.N.; Santamaria, M.P. Local adjunct effect of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy for the treatment of chronic periodontitis in type 2 diabetics: Split-mouth double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talebi, M.; Taliee, R.; Mojahedi, M.; Meymandi, M.; Torshabi, M. Microbiological efficacy of photodynamic therapy as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal treatment: A clinical trial. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 7, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martins, F.; Simões, A.; Oliveira, M.; Luiz, A.C.; Gallottini, M.; Pannuti, C. Efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as an adjuvant in periodontal treatment in Down syndrome patients. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1977–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarese, G.; Ramaglia, L.; Cicciu, M.; Cordasco, G.; Isola, G. The effects of diode laser therapy as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis: A 1-Year Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, G.; Williams, R.C.; Siciliano, V.I.; Alibrandi, A.; Cordasco, G.; Ramaglia, L. The effects of a desiccant agent in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadore, U.B.; Reis, M.B.L.; Martins, S.H.L.; Invernici, M.D.M.; Novaes, A.B., Jr.; Taba, M., Jr.; Palioto, D.B.; Messora, M.R.; Souza, S.L.S. Multiple sessions of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy associated with surgical periodontal treatment in patients with chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borekci, T.; Meseli, S.E.; Noyan, U.; Kuru, B.E.; Kuru, L. Efficacy of adjunctive photodynamic therapy in the treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Lasers Surg. Med. 2019, 51, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Gaspirc, B.; Sculean, A. Clinical and microbiological effects of multiple applications of antibacterial photodynamic therapy in periodontal maintenance patients. A randomized controlled clinical study. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, F.H.; Koppolu, P.; Tanvir, S.B.; Samran, A.; Alqerban, A. Clinical efficacy of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis among HIV seropositive patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 29, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, E.P.; Murakami-Malaquias-Silva, F.; Schalch, T.O.; Teixeira, D.B.; Horliana, R.F.; Tortamano, A.; Tortamano, I.P.; Buscariolo, I.A.; Longo, P.L.; Negreiros, R.M.; et al. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy and periodontal treatment in patients with gingivitis and fixed orthodontic appliances: Protocol of randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Medicine 2020, 99, e19429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nazeh, A.; Alshahrani, A.; Almoammar, S.; Kamran, M.A.; Togoo, R.A.; Alshahrani, I. Application of photodynamic therapy against periodontal bacteria in established gingivitis lesions in adolescent patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 31, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, S.; Prakash, S.; Jagadeson, M.; Namachivayam, A.; Das, D.; Sarkar, S. Clinico-microbiological efficacy of indocyanine green as a novel photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy among patients with chronic periodontitis: A split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patyna, M.; Ehlers, V.; Bahlmann, B.; Kasaj, A. Effects of adjunctive light-activated disinfection and probiotics on clinical and microbiological parameters in periodontal treatment: A randomized, controlled, clinical pilot study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 3967–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llanos do Vale, K.; Ratto Tempestini Horliana, A.C.; Romero dos Santos, S.; Oppido Schalch, T.; Melo de Ana, A.; Agnelli Mesquita Ferrari, R.; Kalil Bussadori, S.; Porta Santos Fernandes, K. Treatment of halitosis with photodynamic therapy in older adults with complete dentures: A randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 33, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Momani, M.M. Indocyanine-mediated antimicrobial photodynamic therapy promotes superior clinical effects in stage III and grade C chronic periodontitis among controlled and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.G.; de Godoy, C.H.L.; Deana, A.M.; de Santi, M.E.S.O.; Prates, R.A.; França, C.M.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Bussadori, S.K. Photodynamic therapy as a novel treatment for halitosis in adolescents: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014, 15, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lopes, R.G.; da Mota, A.C.C.; Soares, C.; Tarzia, O.; Deana, A.M.; Prates, R.A.; França, C.M.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Ferrari, R.A.M.; Bussadori, S.K. Immediate results of photodynamic therapy for the treatment of halitosis in adolescents: A randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Mota Ciarcia, A.C.C.; Gonçalves, M.L.L.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Suguimoto, E.S.A.; Araujo, L.; Laselva, A.; Mayer, M.P.A.; Motta, L.J.; Deana, A.M.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; et al. Action of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy with red leds in microorganisms related to halitose: Controlled and randomized clinical trial. Medicine 2019, 98, e13939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, S.D.S.; Schalch, T.O.; Do Vale, K.L.; Ando, E.S.; Mayer, M.P.A.; Feniar, J.P.G.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Bussadori, S.K.; Motta, L.J.; Negreiros, R.M.; et al. Evaluation of halitosis in adult patients after treatment with photodynamic therapy associated with periodontal treatment: Protocol for a randomized, controlled, single-blinded trial with 3-month follow up. Medicine 2019, 98, e16976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.L.L.; da Mota, A.C.C.; Deana, A.M.; de Souza Cavalcante, L.A.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Pavani, C.; Motta, L.J.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; da Silva, D.F.T.; et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy with Bixa orellana extract and blue LED in the reduction of halitosis—A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 30, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A.A.; Alhaizaey, A.; Kamran, M.A.; Alshahrani, I. Efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy against halitosis in adolescent patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 32, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, S.S.; do Vale, K.L.; Remolina, V.G.; Silva, T.G.; Schalch, T.O.; Ramalho, K.M.; Negreiros, R.M.; Ando, E.S.; Mayer, M.P.A.; Mesquita Ferrari, R.A.; et al. Oral hygiene associated with antimicrobial photodynamic therapy or lingual scraper in the reduction of halitosis after 90 days follow up: A randomized, controlled, single-blinded trial. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 33, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M.; Schär, D.; Wicki, B.; Eick, S.; Ramseier, C.A.; Arweiler, N.B.; Sculean, A.; Salvi, G.E. Anti-infective therapy of peri-implantitis with adjunctive local drug delivery or photodynamic therapy: 12-month outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2014, 25, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakašević, D.; Lazic, Z.; Rakonjac, B.; Soldatovic, I.; Jankovic, S.; Magic, M.; Aleksic, Z. Efficiency of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of peri-implantitis: A three-month randomized controlled clinical trial. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2016, 144, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karimi, M.R.; Hasani, A.; Khosroshahian, S. Efficacy of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy as an Adjunctive to Mechanical Debridement in the Treatment of Peri-implant Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 7, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ichinose-Tsuno, A.; Aoki, A.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kirikae, T.; Shimbo, T.; Lee, M.-C.; Yoshino, F.; Maruoka, Y.; Itoh, T.; Ishikawa, I.; et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy suppresses dental plaque formation in healthy adults: A randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.A.S.; Rolim, J.P.M.L.; Passos, V.F.; Lima, R.A.; Zanin, I.C.J.; Codes, B.M.; Rocha, S.S.; Rodrigues, L.K.A. Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy and ultraconservative caries removal linked for management of deep caries lesions. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2015, 12, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asnaashari, M.; Ashraf, H.; Rahmati, A.; Amini, N. A comparison between effect of photodynamic therapy by LED and calcium hydroxide therapy for root canal disinfection against Enterococcus faecalis: A randomized controlled trial. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 17, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Santos, L.; Silva-Júnior, Z.S.; Sfalcin, R.A.; da Mota, A.C.C.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Motta, L.J.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Prates, R.A.; Silva, D.F.T.; et al. The effect of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy on infected dentin in primary teeth: A randomized controlled clinical trial protocol. Medicine 2019, 98, e15110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, C.B.; Bussadori, S.K.; Prates, R.A.; da Mota, A.C.C.; Tempestini Horliana, A.C.R.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Motta, L.J. Photodynamic therapy for endodontic treatment of primary teeth: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 30, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.P.V.; Paolillo, F.R.; Parmesano, T.N.; Fontana, C.R.; Bagnato, V.S. Effects of Photodynamic Therapy with Blue Light and Curcumin as Mouth Rinse for Oral Disinfection: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2014, 32, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morley, S.; Griffiths, J.; Philips, G.; Moseley, H.; O’Grady, C.; Mellish, K.; Lankester, C.L.; Faris, B.; Young, R.J.; Brown, S.B.; et al. Phase IIa randomized, placebo-controlled study of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in bacterially colonized, chronic leg ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers: A new approach to antimicrobial therapy. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 168, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.C. Periodontal Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cortelli, J.R.; Barbosa, M.D.S.; Westphal, M.A. Halitosis: A review of associated factors and therapeutic approach. Braz. Oral Res. 2008, 22, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwarz, F.; Derks, J.; Monje, A.; Wang, H. Peri-implantitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S246–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).