Abstract

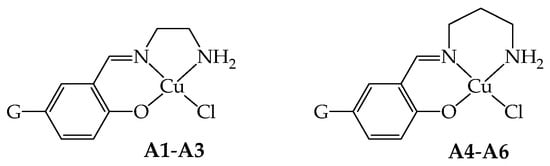

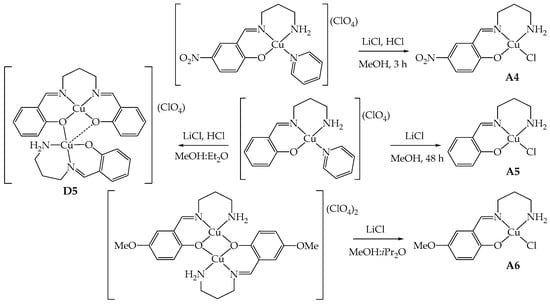

The copper(II) complexes of general formula [Cu(GL2H,H)(Cl)] (A4–A6, G = NO2, H and OMe, respectively), bearing NNO tridentate Schiff base ligands (GL2H,H)− derived from the mono-condensation of 1,3-diaminopropane and G-substituted salicylaldehydes, are here reported. The elongation of the diamine with one additional carbon atom with respect to the triad derived from ethylenediamine [Cu(GL1H,H)(Cl)] (A1–A3, G = NO2, H and OMe, respectively) led to different synthetic procedures, with the difficult isolation of A6 that could be obtained only in few crystals suitable for X-ray diffractions. Operating in acidic conditions to promote the coordination of chloride and expulsion of pyridine from the complex [Cu(GL2H,H)(py)](ClO4) (G = NO2) allows for obtaining A4. On the other hand, structural rearrangement occurs when G = H, yielding the dinuclear species [Cu2(μ-saltn)(HL2H,H)](ClO4)⋅0.5MeOH (D5⋅0.5MeOH) instead of the desired A5, which can be obtained by avoiding the use of HCl and operating in the excess of LiCl. Finally, A4 and A5 were investigated as cytotoxic agents against malignant (MDA-MB-231 and 22-Rv1) and healthy (HaCaT) cell lines, and the ability of the most promising A5 to be internalized and interact with cellular targets was studied.

1. Introduction

Copper(II) [1,2,3,4] complexes with oligodentate Schiff base ligands derived from variously substituted salicylaldehydes and aliphatic primary diamines, such as ethylenediamine (en) and 1,3-diaminopropane (tn), have always been at the center of our research activity. The reactivity of en and tn towards salH is indeed high, so that the mono-condensation product, i.e., the so-called “half units” [5,6], can be achieved upon template synthesis, yielding the tridentate ligands already coordinated to the templating metal ion [7,8]. These products have been studied for their nonlinear optical properties [3], magnetic properties [1,2], and, more recently, also as possible cytotoxic agents [4].

The potential application of copper(II) complexes with NNO tridentate Schiff bases as possible antitumor drugs arises from various considerations: (i) platinum-based anticancer drugs [9], nowadays largely employed as first therapeutic choice, cannot be used to treat all tumors and they are accompanied by serious side effects [10]: metal-based drugs with alternative mode of action could offer better therapeutic alternatives; (ii) some biological pathways where copper acts as an essential element are enriched during cancer progression [11], and this highlights how copper(II) plays a central role in anticancer research [12,13], as underlined also by studies on cuproptosis [14,15]; (iii) there are complexes with Schiff base ligands derived from substituted salH that have demonstrated their efficiency as anticancer agents [16,17,18,19].

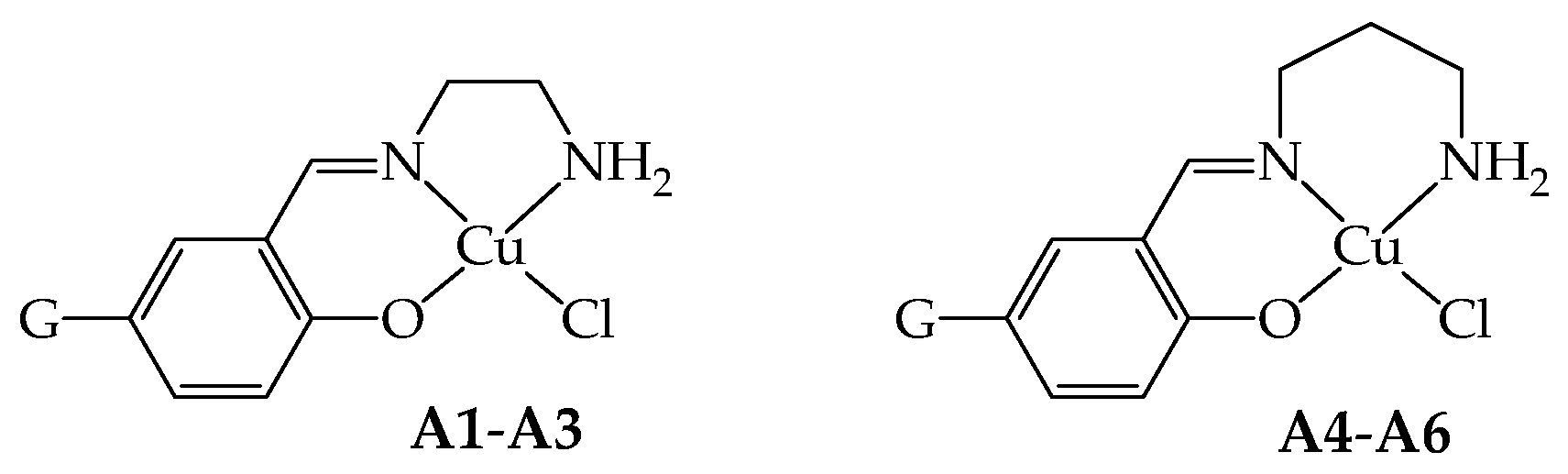

As a continuation of the research in this direction, in this paper, we present the copper(II) complexes of general formula [Cu(GL2H,H)(Cl)] (A4–A6, G = NO2, H, and OMe, respectively; Scheme 1), bearing NNO tridentate Schiff base ligands (GL2H,H)− derived from the mono-condensation of tn and G-salH. This triad of complexes joins the previous one [Cu(GL1H,H)(Cl)] (A1–A3, G = NO2, H, and OMe, respectively, Scheme 1) derived from en [4]. To note that little variations on the ligand scaffold could tune important features of the corresponding metal complexes, such as lipophilicity, solubility, and stability towards biological competitors, leading to favorable pharmacological profiles. In this case, we focused our attention on the elongation of the diamine with one additional carbon atom. The peculiarity in both the reactivity and the structural and biological features associated with this very little but subtle variation in the tridentate ligand [2] will be highlighted.

Scheme 1.

Scheme of the NNO coordination behavior of the ligands in the copper(II) complexes A1–A3 (G = NO2, H, OMe, respectively) and A4–A6 (G = NO2, H, OMe, respectively).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthetic Studies

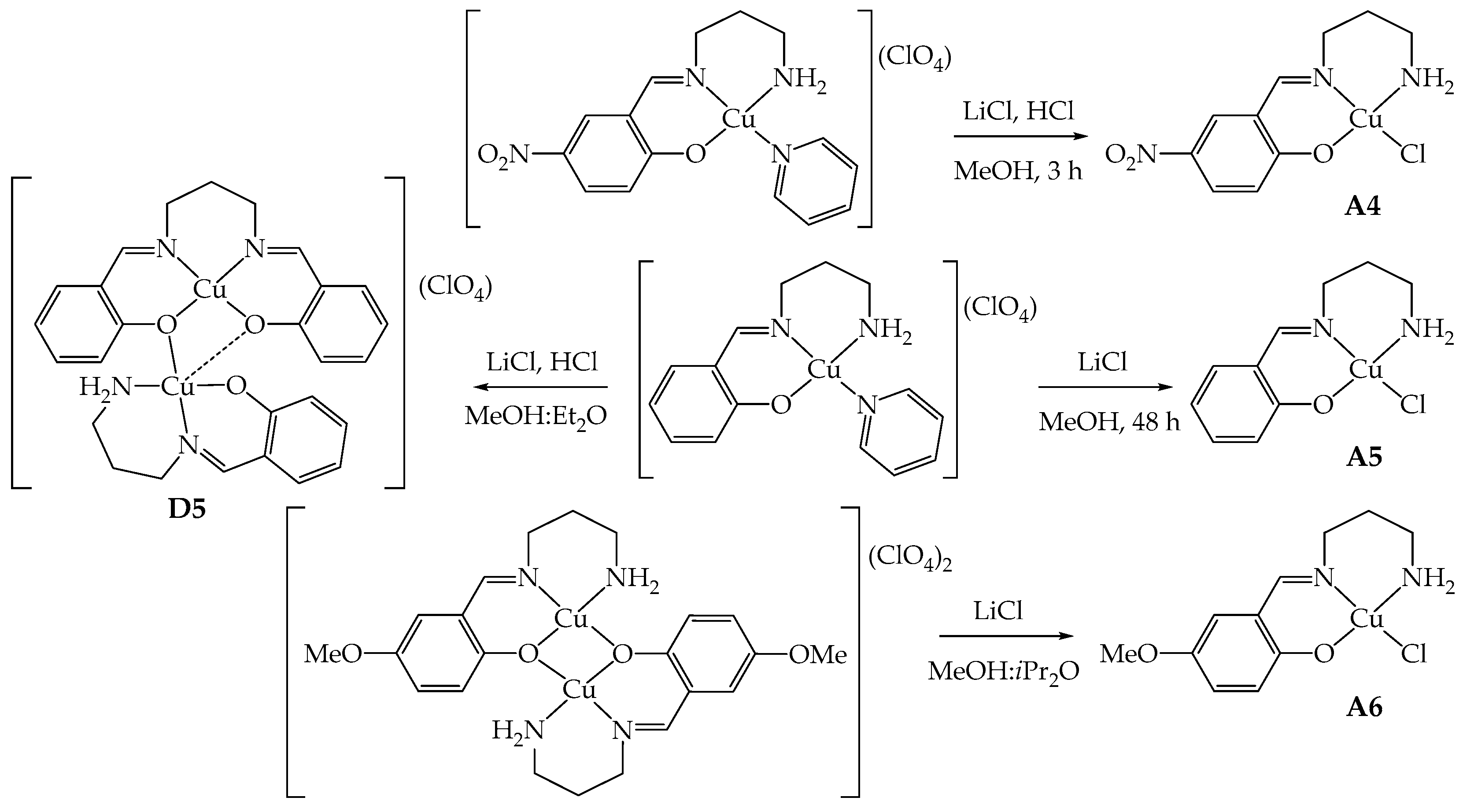

Compounds A4–A6, similar to A1–A3 [4], share the characteristic of possessing only one imino group derived from the condensation of tn with G-salH and one primary amino group able to coordinate to copper(II) (Scheme 1). The synthetic strategy adopted to obtain these derivatives is then a template one to avoid double condensation [1,4]. The mononuclear [Cu(GL2H,H)(py)](ClO4) (G = NO2, H) [1] and the dinuclear [Cu2(μ-OMeL2H,H)2](ClO4)2 [1,20] were employed as starting reagents, and they were reacted in MeOH with lithium chloride either in the presence of HCl or without the addition of acid, depending on the starting precursor compound [4].

In general, these reactions seem to occur in a few minutes, as evidenced by the precipitation of green solids; probably, this is due to the low solubility of the final products as neutral compounds in a polar solvent, such as MeOH. However, given the non-complete solubility of the precursors in the reaction solvent, the mixtures were kept stirring for at least 3 h at room temperature (RT) to ensure either the complete substitution of the pyridine or opening of the dinuclear species by the chloride ion.

In the case of A5 (G = H), the optimal reaction conditions involve longer reaction times (48 h), an excess of LiCl in the absence of HCl, since the imine bond of the precursor seems more sensitive to acids than the corresponding en derivative A2 [4], undergoing hydrolysis and double condensation, as detected by mass spectrometry (Scheme 2). The reaction yield for A5 is still good (59%) even in the absence of acid. Indeed, when employing only LiCl, the crystallization of the reaction mixture led to crystals of A5, while when HCl is present, the crystallization led to [Cu2(μ-saltn)(HL2H,H)](ClO4)⋅0.5MeOH (D5⋅0.5MeOH) as single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction. This dinuclear species is evidently the result of a rearrangement in solution, and saltn (N,N′-bis(salicylidene)-1,3-diaminopropane) results from the double-condensation reaction (see structural characterization below).

Scheme 2.

Schematic representation of the synthesis of A4–A6 and formation of D5.

For the synthesis of A4 (G = NO2), instead, there is no sign of hydrolysis even in the presence of HCl. The reaction could be then conducted with the addition of LiCl and aqueous HCl to protonate the pyridine and favor the coordination of chloride within only 3 h of reaction time (Scheme 2). The yield is about 85% thanks to the low solubility conferred by the nitro group.

The reaction of [Cu2(μ-OMeL2H,H)2](ClO4)2 with LiCl in a four- or ten-fold excess at RT or under reflux never led to the desired product A6, in contrast with what was observed with A3 [4]. In all cases, the starting material was isolated from the mother liquor, as confirmed by elemental analysis and infrared spectra. Few green crystals of A6, suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis, could be isolated by using a large excess of LiCl (10 equivalents vs. the starting reagent) and liquid diffusion of iPr2O into the reaction mixture, after removal of emerald green crystals of unreacted [Cu2(μ-OMeL2H,H)2](ClO4)2 (corresponding to 80%). Probably, a very large excess of chloride anions and a more diluted solution in a MeOH-iPr2O mixture concur to the stabilization of A6 in the solid state (Scheme 2). Unfortunately, the amount of isolated crystals was insufficient for its subsequent use.

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy is extremely useful and provided unquestionable confirmation of the success of the synthesis, especially referring to the stretching signals of N–H bonds that undergo a significant shift when passing from the starting reagents to the product. In particular, signals move from 3313 and 3253 cm−1 for [Cu(NO2L2H,H)(py)](ClO4) [1] to 3253 and 3213 cm−1 for A4 and from 3315 and 3256 cm−1 for [Cu(HL2H,H)(py)](ClO4) [1] to 3308 and 3228 cm−1 for A5 (Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials). This is probably caused by the involvement of the amino groups in H-bonds stabilizing the dimeric units in the solid state (see structural characterization of A5 for further details), confirming what we already observed with the previous triad A1–A3 [4]. Furthermore, the perchlorate stretching band at about 1100 cm−1, present in the starting complexes, disappeared in the final compounds A4 and A5. Elemental analysis and mass spectrometry further confirmed the proposed stoichiometry.

2.2. Structural Characterizations

As stated above and in the Experimental Section, single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained upon slow diffusion of iPr2O into the MeOH reaction mixture for A5 and A6, or Et2O into the acidic MeOH reaction mixture for D5⋅0.5MeOH, while any attempt to obtain crystals of A4 failed.

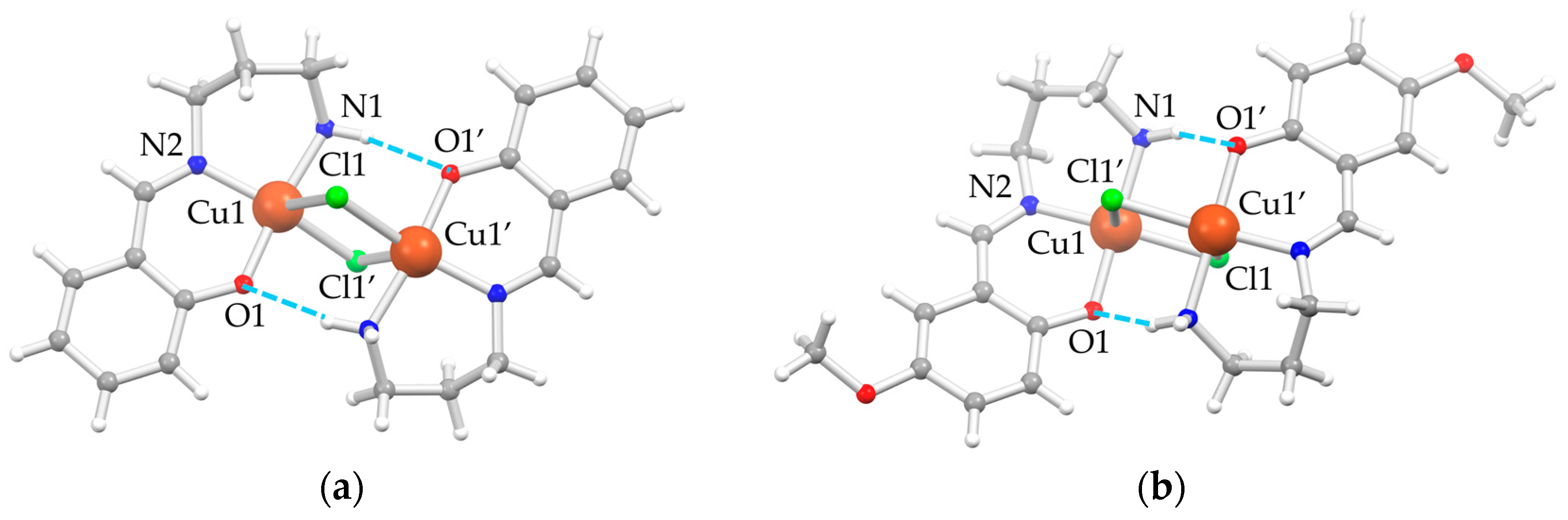

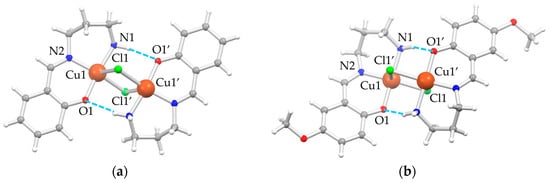

In the solid state, both A5 (G = H) and A6 (G = OMe) crystallize in the monoclinic P21/c space group. The asymmetric unit is composed by one [Cu(GLH,H)(Cl)] independent moiety, which assembles to give dimeric units [Cu2(μ-Cl)2(GL2H,H)2] with chloride ions, bridging the two copper(II) ions, confirming what was previously observed for A2 [4,21] and A3 [4]. Structural depictions are reported in Figure 1, and a selection of bond distances and angles are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Depiction of the molecular structure of the dimeric units of (a) A5 and (b) A6 as ball-and-stick style [22] with main atom numbering; color code: Cu = orange, Cl = green, O = red, N = blue, C = gray, H = white, H-bonds = dashed azure lines.

Table 1.

Main coordination distances (Å) and angles (°) of A5 and A6.

The rhombic four-membered Cu2Cl2-bridging units are strictly planar, owing to the crystallographic inversion center. The coordination environment of each copper(II) ion is well described as square pyramidal, where the square plane is formed by the NNO set from the (GLH,H)− ligands, and the fourth position is occupied by the chloride ion, which also behaves as a fifth ligand for the adjacent copper(II) ion of the inversion-symmetry-related molecule. The chloride bridge is asymmetric, with a short Cu–Cl bond in the square, albeit distorted, coordination plane and a longer one as the fifth, almost-apical interaction. There are also moderately strong intramolecular N1–H⋅⋅⋅O1′ hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) (d(H⋅⋅⋅O1) = 2.19 Å, d(N1⋅⋅⋅O1) = 3.069(1) Å, angle N1–H⋅⋅⋅O1 = 162.0° for A5, and d(H⋅⋅⋅O1) = 2.41 Å, d(N1⋅⋅⋅O1) = 3.193(2) Å, angle N1–H⋅⋅⋅O1 = 147.4° for A6) between the hydrogen of the amino group of one moiety and the phenolic oxygen of the other one to consolidate the dimeric unit.

The distortion of the copper(II) N2OCl square planar coordination plane is more pronounced in A5 than in A6 essentially due to the position of the chloride. This is clearly evident from both the distances and angles involving the anion (Table 1) and its distance from the plane through the N2OCu atoms of the [Cu(GL2H,H)]+ unit (1.24 and 0.85 Å for A5 and A6, respectively, against 1.06 and 0.68 Å for A2 and A3, respectively [4]). This is a direct consequence of the shorter Cu1–Cl1 distance in A6 (2.2868(5) Å) compared to A5 (2.3523(5) Å), which subsequently leads to a longer Cu1–Cl1′ apical interaction in A6 (2.8430(5) Å) compared to A5 (2.6984(6) Å) and a more acute rhombus in A6 with respect to A5. No other significant differences in coordination bond lengths of the two complexes are highlighted. The greater flexibility conferred by the tn bridge of three CH2 units between the two nitrogen atoms compared to en derivatives A1–A3 [4] leads to a twist conformation in A6 and a boat conformation in A5 of the six-membered metallacycle.

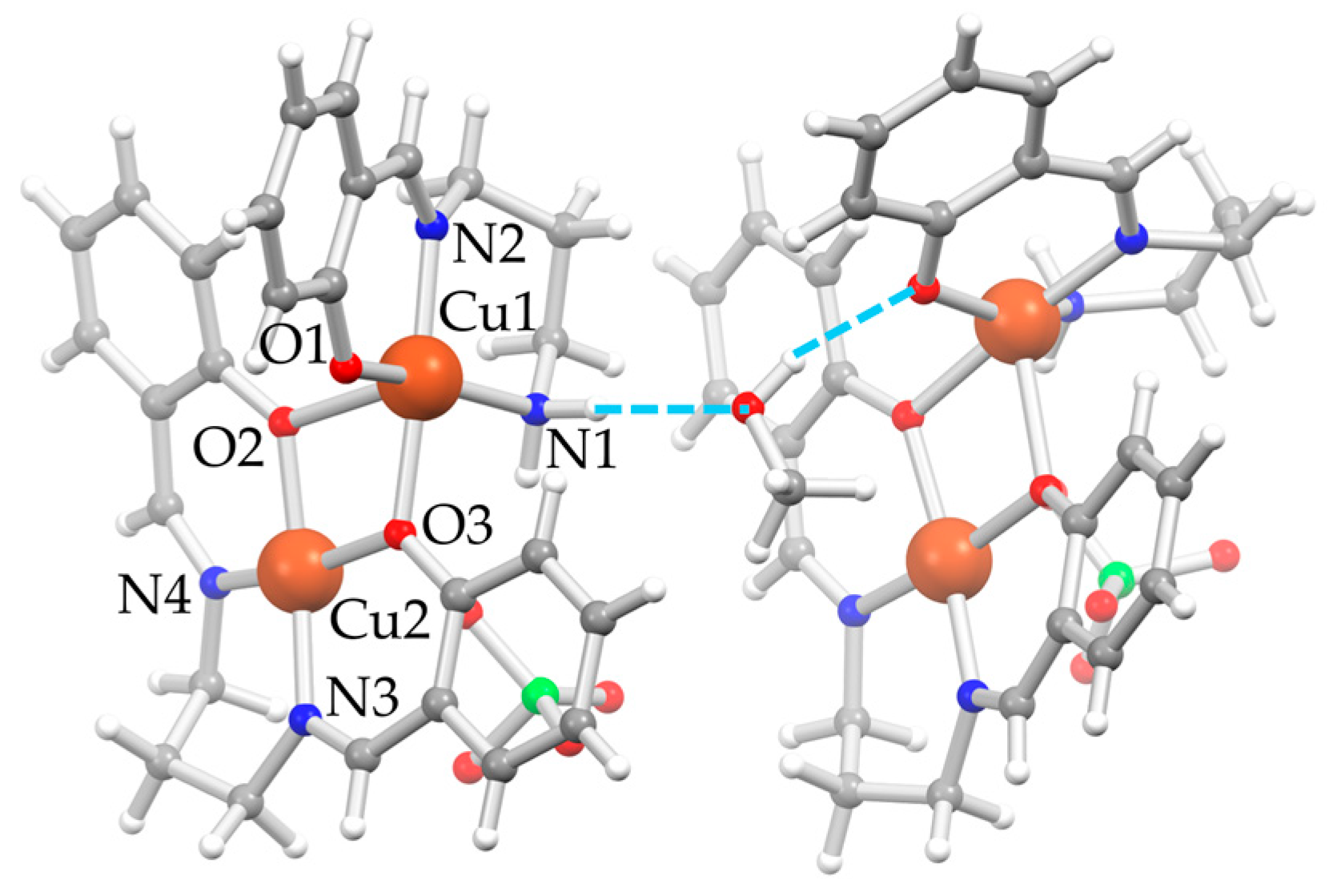

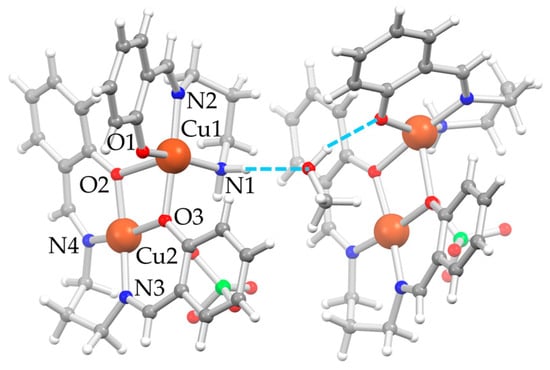

D5⋅0.5MeOH also crystallizes in the monoclinic P21/c space group. The asymmetric unit is composed of two independent [Cu2(μ-saltn)(HL2H,H)](ClO4) moieties, called A and B, and one MeOH molecule between the two units, consolidating the overall crystal packing (Figure 2). Both moiety A and B are composed by [Cu(HL2H,H)]+ and [Cu(saltn)] subunits, the latter deriving from the double condensation of two sal− units to tn to give the saltn tetradentate ligand coordinated to copper(II). This agrees with what is observed in the precipitated solid, where both fragments could be detected in the mass spectrum. A selection of bond distances and angles of D5⋅0.5MeOH is reported in Table 2. The oxygen atoms of [Cu(saltn)] form an unsymmetric double bridge, coordinating the first copper(II) ion with the tridentate ligand (Cu1) and bringing its final coordination to a square-based pyramid. The perchlorate anions deriving from the precursor balance the overall charge by forming a fifth apical interaction on the second copper(II) ion (Cu2⋅⋅⋅OClO3) and bringing also Cu2 to a square pyramidal coordination.

Figure 2.

Depiction of the molecular structure of D5⋅0.5MeOH as ball-and-stick style [22] with main atom numbering for unit A on the left; unit B on the right has a very similar orientation in the crystal, and the same atom numbering is applied, even if not reported; color code: Cu = orange, Cl = green, O = red, N = blue, C = gray, H = white, H-bonds = dashed azure lines.

Table 2.

Main coordination distances (Å) and angles (°) of D5⋅0.5MeOH.

The MeOH molecule remains trapped between the two dinuclear units A and B, involved in relatively strong H-bonds, one with the amino nitrogen atom of unit A as an acceptor (N1–H⋅⋅⋅OMe, d(H⋅⋅⋅OMe) = 2.08 Å, d(N1⋅⋅⋅OMe) = 2.976(4) Å, angle N1–H⋅⋅⋅OMe = 168.0°) and one with the phenolic oxygen atom of the tridentate ligand of unit B as a donor (MeO–H⋅⋅⋅O1, d(H⋅⋅⋅OMe) = 1.95 Å, d(N1⋅⋅⋅OMe) = 2.766(3) Å, angle N1–H⋅⋅⋅OMe = 163.0°). One perchlorate anion and the methyl group of the MeOH are disordered over two positions.

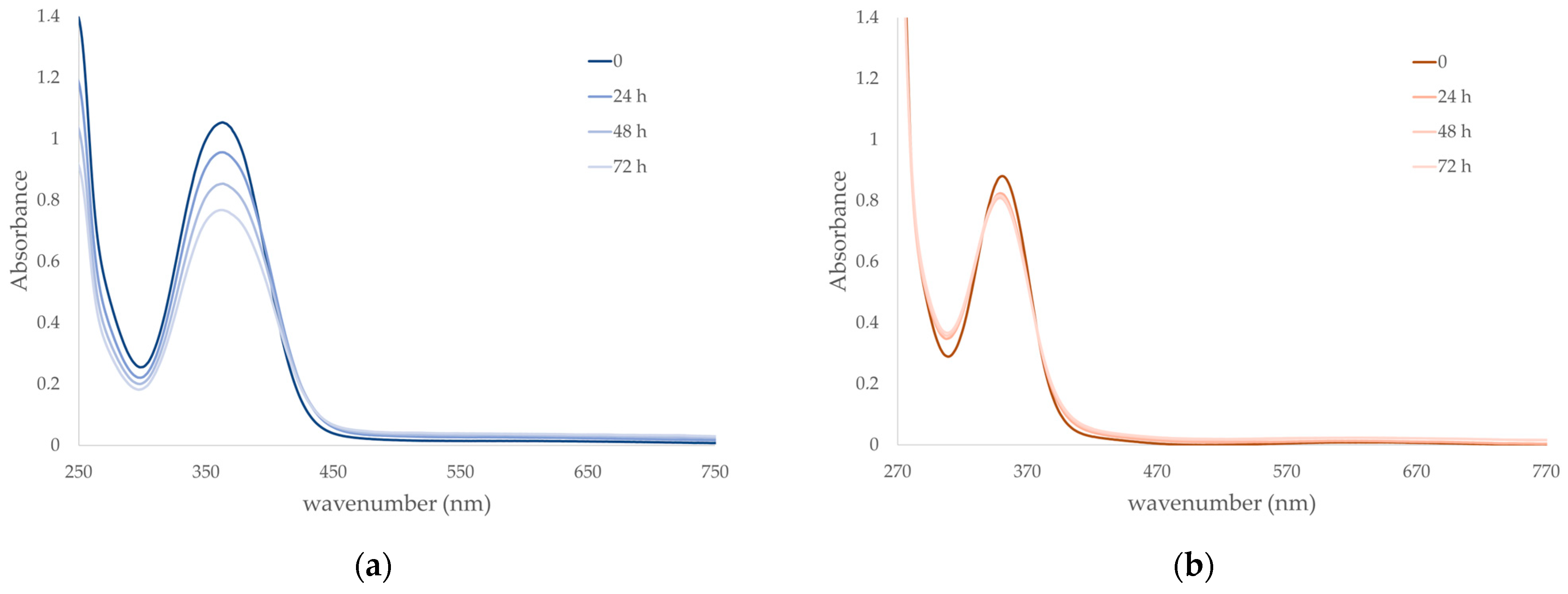

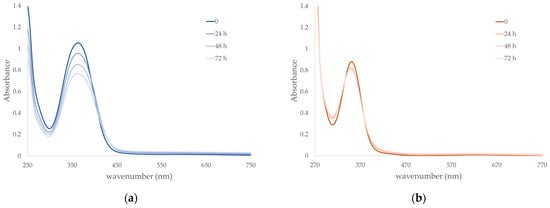

2.3. Stability in Solution

The chemical stability of the compounds once dissolved in aqueous solution in the μmol L−1 regime is crucial for understanding the potential application as cytotoxic agents [23]. Copper(II) derivatives with Schiff base ligands absorb in the UV/Vis region with a characteristic profile given by a convolution of ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) and π → π* transitions at about 300–400 nm [3]. Thus, similarly to A1–A3 [4], the stability of A4 and A5 in mimicked physiological conditions, 37 °C in darkness in saline phosphate-buffer solution (PBS) at pH = 7.4, was investigated by means of UV/Vis spectroscopy over a period of 72 h (Figure 3). The dilution reached for reliable spectra resembles the conditions employed during in vitro tests (see below). Water as solvent can establish H-bonds with the complexes in substitution of the N–H⋯O interactions observed in the X-ray crystal structures. This allows us to confidently assume that dimeric units should not persist when moving from solid state to solution. The solvated cation [Cu(GL2H,H)(H2O)n]+ (with n from 1 to 3) is expected to be the predominant species due to labilization of the monodentate chloride ion by water. In support of this view, which is also in line with what was observed for A1–A3 [4], the solvated [Cu(NO2L1H,H)(H2O)](ClO4)⋅H2O [1] and the homologous with the chiral 1,2-diphenylethylenediamine [3] could also be fully characterized in the solid state, thus confirming the existence of the solvated species.

Figure 3.

Kinetic stability in solution through UV/Vis spectroscopy of (a) A4 (7.3 10−5 mol L−1) and (b) A5 (1.9 10−4 mol L−1) in saline PBS 0.01 mol L−1 at pH 7.4 and constant ionic strength of 0.1 mol L−1 with addition of NaCl, at 37 °C in darkness during 72 h.

From the UV/Vis spectra of A4 and A5 analyzed in mimicked physiological conditions, it can be noted that the two compounds show absorption maxima at 363 (A4) and 351 nm (A5) with ε values (A4: 14400 L mol−1 cm−1 and A5: 4600 L mol−1 cm−1) at the initial time completely comparable to the values obtained for the similar complexes A1 and A2 [4]. On the other hand, absorption profile diminishes with time for A4, reaching about 75% of the initial value within 72 h, while maintaining similar shape and maximum value. This can be explained either as slow and gradual degradation of the complex or formation of a different species with the same absorption but different ε value; nonetheless, sufficient stability is guaranteed. In the case of A5, a very slight decrease in absorbance values can also be observed, reaching about 93% of the initial value within 72 h, together with a concomitant shift to slightly lower wavelengths of the absorption maximum (349 nm after 72 h) and formation of an isosbestic point, and this seems to highlight the presence of some equilibria in solution. Indeed, the flexibility of the tn bridge might give rise to the partial detachment of the coordinated amino group and opening of the six-member metallacycle with replacement with a water molecule or phosphate ion. This would justify not only the survival of the absorption profile with no alteration of the tridentate ligand, since its LMCT + π → π* transitions are preserved, but also the difference with the behavior of A1 and A2, the counterpart with en, where the reduced flexibility of the five-member metallacycle does not lead to any alteration in solution [4].

2.4. Biological Studies

The in vitro inhibitory activity of A4 and A5 on viability after 24 h exposure was screened in the human malignant cell lines MDA-MB-231 (breast cancer-derived) and 22-Rv1 (prostate cancer-derived), and healthy cell line HaCaT (keratinocytes) with the MTT assay. The data obtained were compared to the inhibitory activity of the conventional chemo-therapeutic agent cisplatin (CDDP) under the same conditions (Table 3). Similarly to the previous triad A1–A3 [4], the complex bearing the nitro group A4 shows the highest reduction in cell viability with respect to MDA-MB-231 cell line (28.4 μmol L−1), even if less pronounced than A1 (17.9 μmol L−1). On the other hand, A5 is the most active against 22-Rv1 cell line, and it is also more active than CDDP. Unfortunately, there is a minimal difference in cytotoxicity between A4 and A5 when compared to the healthy HaCaT cell line. Although non-selectivity could pose a challenge in in vivo settings, this issue may potentially be addressed by using drug delivery systems capable of selectively targeting cancer cells [24].

Table 3.

24hIC50 values (μmol L−1) of A4, A5 and CDDP against cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231 and 22-Rv1, together with healthy HaCaT cells.

A5 was then selected for further studies; first, the cell uptake after 24 h was investigated (Figure S2 in Supplementary Materials). In this experiment, the cells, treated with 40 µmol L−1 of A5 for 24 h, were washed with EDTA after the treatment to remove any molecule accumulated on the membrane, thus analyzing only the intracellular content of copper. The highest intracellular level of metal was detected for MDA-MB-231, but this is not correlated to the cytotoxic activity, highlighting the different mechanisms of cell proliferation and inherent susceptibility to the action of the compound. As copper complexes are well known to bind DNA via a variety of covalent and non-covalent interactions [25], we next performed an investigation of the in vitro interaction between A5 and genomic DNA (gDNA) to delineate possible mode of action. As shown in Figure S3 in Supplementary Materials, A5 displayed the capability to competitively remove (and thus quench) Ethidium bromide (EtBr) from gDNA. This finding clearly corroborates the intercalating activity of the complex, as previously observed for A2 [4]. Subsequently, nuclease activity (DNA cleavage) of A5 was investigated by analysis of cleavage of pBR322 plasmid DNA (pDNA, form II) after an incubation for 24 h at 37 °C: pDNA started to disappear at the highest applied concentration, indicating extensive damage to pDNA (Figure S4 in Supplementary Materials).

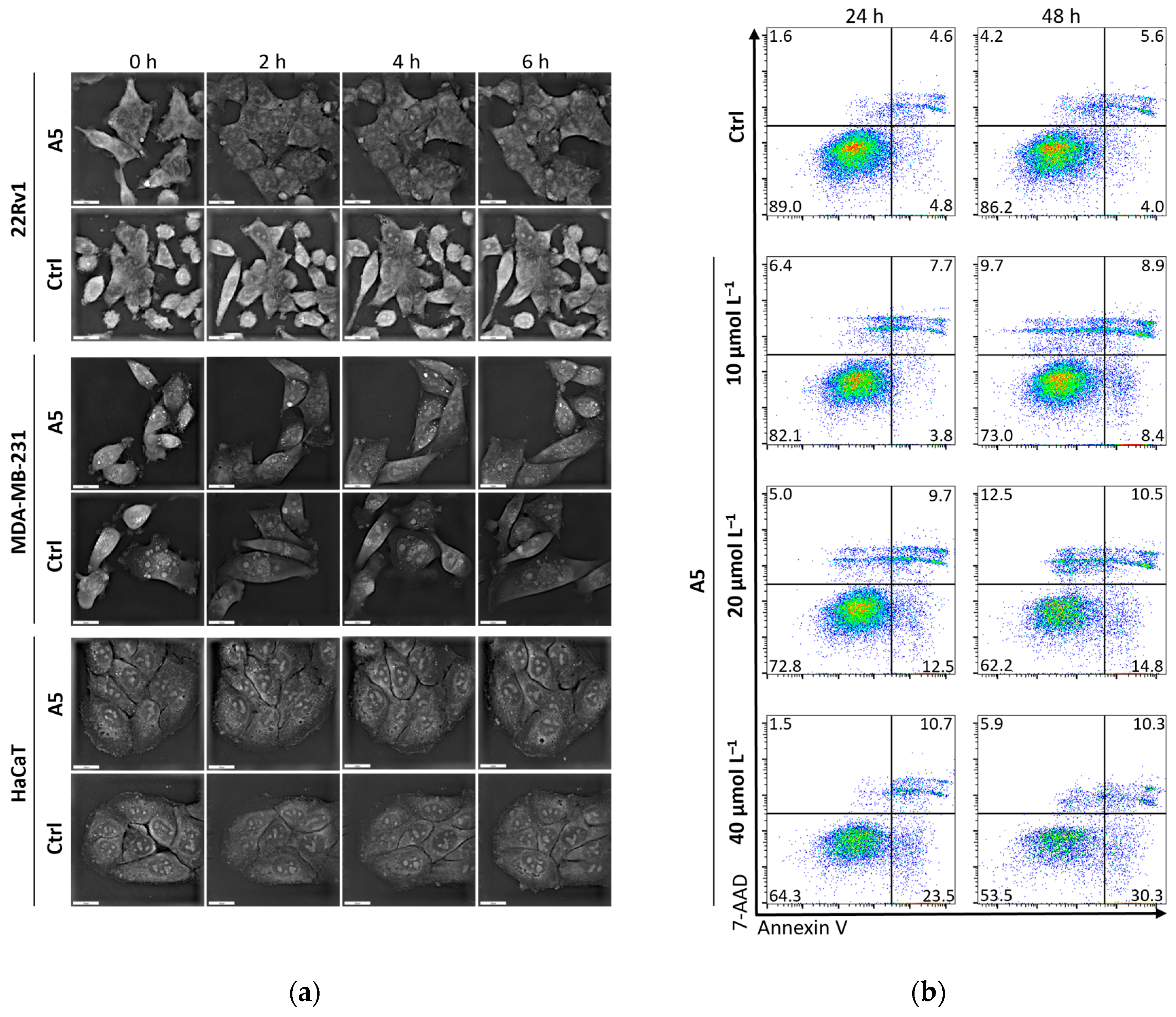

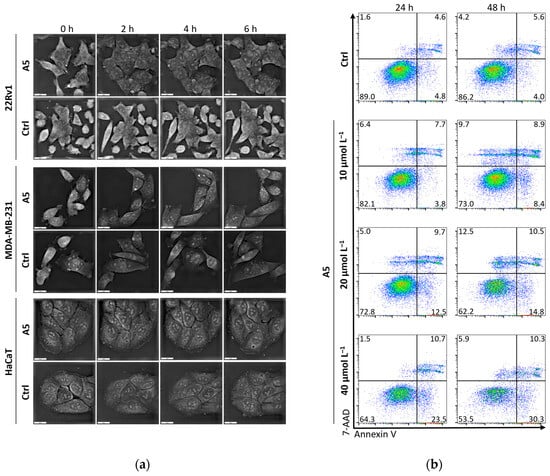

A short-term analysis (0–6 h) on cell morphology through holotomography was performed at a concentration of 40 μmol L−1 of A5 on all cell lines (Figure 4). Some morphological features suggest onset of apoptosis, particularly in 22Rv1 cells where the 24hIC50 is 26.2 μmol L−1, i.e., lower than the applied concentration. In this regard, flow cytometry dot plots of Annexin V/7-AAD-stained 22Rv1 cells treated with an increasing amount of A5 analyzed after 24 and 48 h treatments confirm the dose- and time-dependent ability of the complex to induce apoptosis.

Figure 4.

(a) Short-term analysis (0–6 h) of effects of A5 at a concentration of 40 μmol L−1 on cell morphology analyzed by holotomography; scale bar, 20 μm. (b) Flow cytometry dot plots showing Annexin V/7-AAD-stained 22Rv1 cells treated with annotated concentrations of A5 analyzed after 24 and 48 h treatments.

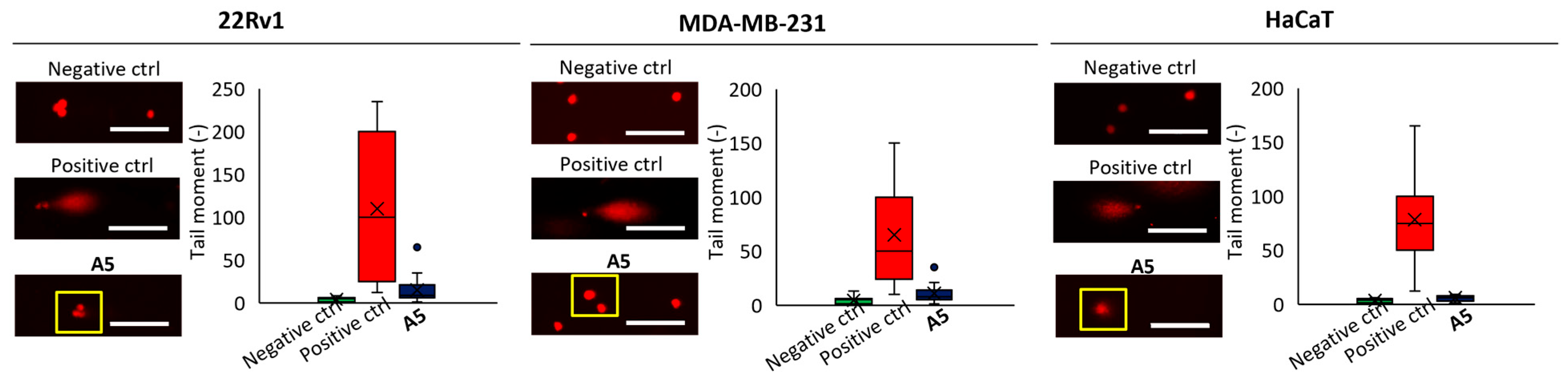

To further validate the capability of A5 to damage DNA in cells, we performed single-cell gel electrophoresis (SCGE), known as comet assay, on the different cell lines at a concentration of 40 μmol L−1 for 6 h and evaluated the intensity of the comet tail and its ratio to the head that reflects the number of DNA breaks in a particular cell. In SCGE, long comet tails are associated with extensive DNA strand breaks and subsequent loss of its supercoiled structure [26]. The highest DNA fragmentation ability was found for 22Rv1 cells, which is in line with the viability data reported in Table 3 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Representative microphotographs of DNA damage induced by A5 (40 μmol L−1, 6 h) detected via single-cell gel electrophoresis; PBS was used as negative control, H2O2 (250 μmol L−1, 1 h) as positive control; scale bar, 100 μm.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

All solvents (MeOH, iPr2O, Et2O, DMSO) and chemicals were reagent-grade and were used as received. Elemental analyses were performed with the Thermo Scientific Flash 2000 (CHNS analyzer) instrument. Mass spectrometry with electrospray ionization (MS-ESI) experiments were performed with an Agilent Technologies 6310A Ion Trap LC-MS(n) spectrometer with an ESI ionization interface on MeOH solutions of the complexes. IR spectra were recorded employing a Jasco FTIR-4700LE spectrophotometer in the Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode with a 2 cm−1 resolution, and the relative intensity of the bands is assigned: strong (s); medium (m); weak (w). UV/Visible spectra were recorded at 37 °C with a Jasco V-570 UV/Vis/NIR spectrophotometer in the 250–800 nm range; λ values are accurate to ±1 nm. [Cu(GL2H,H)(py)](ClO4) (G = NO2, H) [1] and [Cu2(μ-OMeL2H,H)2](ClO4)2 [1,20] were synthesized as reported in the literature. Caution! Perchlorate salts of metal complexes with organic ligands are potentially explosive and must be handled with care and in small amounts.

3.2. Synthesis of [Cu(NO2L2H,H)(Cl)] (A4)

Solid LiCl (23.6 mg, 0.556 mmol) was added to a deep green solution/suspension of [Cu(NO2L2H,H)(py)](ClO4) (249.8 mg, 0.538 mmol) dissolved in MeOH (10 mL), and after 5 min, HCl (540 μL of a 1.0 mol L−1 water solution, 0.540 mmol) was added, yielding the precipitation of an emerald-green solid. The mixture was stirred for 3 h, and then the product was isolated by filtration on Gooch G4, washed with MeOH (2 × 2 mL) and iPr2O (2 × 5 mL), and dried for 2 h under vacuum. Yield: 85.3% (135.0 mg). Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C10H12ClCuN3O3⋅0.25H2O (325.73): C, 36.87; H, 3.87; N, 12.90. Found: C, 36.98; H, 3.67; N, 12.81. IR (ATR): 3253m, 3213m (ν NH2), 1639s (ν iminic C=N), 1472s (ν asym NO2), 1330s (ν sym NO2), 1158m (ν C–O). MS-ESI+ (MeOH): m/z 285 ([Cu(NO2L2H,H)]+, 100%).

3.3. Synthesis of [Cu(HL2H,H)(Cl)] (A5)

Solid LiCl (79.1 mg, 1.87 mmol) was added to a deep green solution/suspension of [Cu(HL2H,H)(py)](ClO4) (249.0 mg, 0.594 mmol) dissolved in MeOH (10 mL), and the mixture was stirred for 48 h at RT with the formation of an emerald-green solid that was isolated by filtration on Gooch G4, washed with MeOH (2 × 2 mL) and iPr2O (2 × 5 mL), and dried for 2 h under vacuum. Yield: 58.6% (96.1 mg). Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C10H13ClCuN2O (276.23): C, 43.48; H, 4.74; N, 10.14. Found: C, 43.64; H, 4.69; N, 9.86. IR (ATR): 3308m, 3228m (ν NH2), 1626s (ν iminic C=N), 1200s (ν C–O). MS-ESI+ (MeOH): m/z 240 ([Cu(HL2H,H)]+, 100%). Liquid diffusion of iPr2O into the left methanol reaction mixture led to green crystals of A5 suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

The synthesis was also conducted under the same reaction conditions of A4 (i.e., with the addition of HCl, lower amount of LiCl, and 3 h under stirring), but the batch of product obtained was revealed to possess a less satisfactory elemental analysis compared to the one obtained without HCl, and the mass peak at m/z 343 attributable to [Cu(saltn)] could also be detected; indeed, crystallization through liquid diffusion of Et2O into the mother liquor led to the formation of green crystals of the dinuclear D5⋅0.5MeOH suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

3.4. Attempts of Synthesis of [Cu(OMeL2H,H)(Cl)] (A6)

Attempts to obtain A6 were performed by reacting [Cu2(μ-OMeL2H,H)2](ClO4)2 dissolved in MeOH and adding LiCl in a fourth or tenth fold, with respect to the starting dinuclear complex, and stirring the reaction mixture at RT or under reflux, but the starting material recrystallized from the mother liquor in all cases upon cooling and slow evaporation of the solvent in about 80% yield. Liquid diffusion of iPr2O into the methanol reaction mixture, left after removal of the emerald-green crystals of the unreacted [Cu2(μ-OMeL2H,H)2](ClO4)2, led to few green crystals of A6 suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

3.5. Single-Crystal X-Ray Data Collection and Structure Determination

Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction experiments were obtained upon slow diffusion of iPr2O or Et2O into the methanol reaction mixtures for A5, D5⋅0.5MeOH, and A6. Crystal data and details of data collection and structural refinement are summarized in Table 4. Intensity data of A5 and D5⋅0.5MeOH were collected at the XRD1 beamline of the Elettra Synchrotron (Trieste, Italy) [27] at 100(2) K using a monochromatic wavelength of 0.7000(1) Å on a Pilatus 2M hybrid-pixel area detector (DECTRIS Ltd., Baden-Daettwil, Switzerland). The crystals were dipped in NHV oil (Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany) and mounted on the goniometer head with nylon loops. During data collections, no crystal decay was observed. Data reductions were performed with XDS [28]. The structures were solved with SHELXT [29] and refined with SHELXL-2018/3 [30] implemented in WinGX—Version 2014.1 system [31]. Intensity data of A6 were collected at 296(2) K on a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy S X-ray diffractometer equipped with a CCD HyPix 6000 detector (Rigaku Co., Tokyo, Japan) operated with a mirror-monochromated microfocus Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å) at 50 kV and 1.0 mA. The structure was solved using direct methods and refined with SHELXL-19 [30] using a full-matrix least-squares procedure based on F2 using all data. Thermal motions for all non-hydrogen atoms for all compounds were treated anisotropically, and hydrogens were included on calculated positions, riding on their carrier atoms, with isotropic Ufactors = 1.2⋅Ueq or Ufactors = 1.5⋅Ueq for methyl groups (Ueq being the equivalent isotropic thermal factor of the bonded non hydrogen atom). The program Mercury version 4.3.1 was used for graphics [22].

Table 4.

Crystallographic and refinement data for A5, A6, and D5⋅0.5MeOH.

3.6. Kinetic Stability in Mimicked Physiological Conditions

The stability of A4 and A5 in darkness at 37 °C was evaluated via UV/Vis spectroscopy as a change in absorbance in the 250–800 nm range during 72 h. Solutions at 7.3 × 10−5 mol L−1 for A4 and 1.9 × 10−4 mol L−1 for A5 were prepared in PBS 0.01 mol L−1 at pH 7.4, with the constant ionic strength of 0.1 mol L−1 maintained with the addition of NaCl (saline PBS) by 25-fold dilution of concentrated aqueous solutions of the complexes (1.8 × 10−3 mol L−1 for A4 and 4.8 × 10−3 mol L−1 for A5).

3.7. Cell Culture Conditions and Screening on Viability Aqnd Intracellular Accumulation

Cell lines used in this study were as follows: (i) MDA-MB-231, human triple-negative breast cancer cells derived from metastatic site: pleural effusion; (ii) 22-Rv1, human prostate carcinoma epithelial cells; and (iii) HaCaT, spontaneously transformed aneuploid immortal keratinocyte cells from adult human skin. All cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The culture media were as follows: DMEM (MDA-MB-231), RPMI-1640 (22-Rv1), and DMEM (HaCaT). The media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and pen/strep (100 U mL−1 and 0.1 mg mL−1). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator Galaxy® 170 R (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

The effects of tested formulations on viability were investigated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. For this purpose, the suspension of 5000 cells in medium (50 μL) was added to each well of 96-well plates and left to adhere overnight. After treatment with annotated concentrations of A4 and A5 for 24 h, the MTT solution (10 μL, 5 mg mL−1 in saline PBS) was added to each well, and the mixture was incubated for further 3 h at 37 °C. Finally, the medium containing MTT solution was replaced with 99.9% DMSO, and the plates were incubated for another 5 min. The absorbance was determined using Tecan Infinite 200 PRO (Tecan, Maennedorf, Switzerland) at λ = 570 nm. The experiments were performed in six independent repetitions.

The amount of intracellular accumulation was performed through atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). Measurements were performed on 280Z AAS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with electrothermal atomization and Zeeman background correction according. Copper was measured at primary wavelength of 324.7 nm (spectral bandwidth 0.5 nm, lamp current 4 mA).

3.8. Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) Displacement Assay

Interaction between DNA and A5 was examined using the EtBr displacement assay. A total of 1 μL of 1 mg mL−1 of calf thymus DNA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was pre-incubated with 3 mL of buffer containing 9 mmol L−1 NaCl, 2 mmol L−1 HEPES, and 3 μmol L−1 EtBr (20 °C, 5 min). After that, annotated concentrations of A5 were added, and after thorough mixing and incubation (20 °C, 10 min), the fluorescence intensity of EtBr was evaluated using a microplate fluorimeter: Infinite M200 PRO (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland, λex = 510 nm and λem = 605 nm). The percentage of fluorescence was plotted against the concentration of each compound.

3.9. Plasmid Cleavage Assay

To determine the ability of A5 to cleave pDNA, supercoiled pDNA (pBR322) (50 ng for each sample) in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mmol L−1) containing 50 mmol L−1 NaCl (pH = 7.2) was mixed with the indicated amount of A5. The samples were diluted with Tris-HCl to a total volume of 10 μL, followed by incubation (1 h, 37 °C); 100 μmol L−1 H2O2 was utilized as the positive control. After incubation, the samples were loaded on 1% neutral agarose gel containing 1 mmol L−1 EDTA (TAE buffer, pH = 8.0), 40 mmol L−1 Tris-acetate, and 0.5 μg mL−1 of EtBr. Electrophoresis was performed in a horizontal slab gel apparatus at 20 °C, 75 V for 90 min. Gels were visualized using Azure c600 (Azure Biosystems, Dublin, CA, USA).

3.10. Flow Cytometry

Apoptotic/death cells were detected using flow cytometry by staining using Annex V and 7-AAD. Prior to experiments, the cells were seeded (~105 cells per well) in 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates and subsequently processed and analyzed using BD Accuri C6 Plus (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to [32]. For evaluation, at least 50,000 events were gathered per sample.

3.11. Single-Cell Gel Electrophoresis (SCGE), Comet Assay

22Rv1, MDA-MB-231, and HaCaT cells were plated at a density of ~105 cells per well in six-well dishes and treated with A5 (40 μmol L−1) for 6 h. After harvesting, 15 μL of the cell suspension was mixed with 75 μL of 0.5% low-melting-point agarose (CLP, San Diego, CA, USA) and layered on one end of a frosted plain glass slide. Then, it was covered with a layer of the low-melting agarose (100 μL). After solidification of the gel, the slides were immersed in a lysing solution (2.5 mol L−1 NaCl, 100 mmol L−1 Na2EDTA, 10 mmol L−1 Tris, pH = 10) containing 1% Triton X-100 and 10% DMSO for overnight incubation at 4 °C. A cold alkaline electrophoresis buffer was poured into the chamber and incubated for 20 min at 4 °C. The electrophoresis was carried at 4 °C for 30 min, at (1.25 V cm−1) and 300 mA. The slides were neutralized (0.4 mol L−1 Tris, pH = 7.5) and then stained with EtBr (2 μg mL−1). The cells were analyzed using EVOS FL Auto Cell Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The content of DNA fragmentation was quantified from fluorescence micrographs captured using the EVOS FL Auto Cell Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The classification of comets was based on the length and the shape of the comet tails, from 0 (no visible tail) to 4 (DNA in tail). As a DNA-fragmenting control, 250 μmol L−1 H2O2 for 1 h was used.

4. Conclusions

In agreement with our previous observations [2], this work aimed to further highlight how the subtle addition of a ”CH2” unit, i.e., moving from en to tn, gives rise to different reactivity and synthetic conditions and also can tune the structural and biological features of copper(II) complexes bearing NNO tridentate Schiff bases derived from the condensation of the already-mentioned aliphatic diamines with G-salH. The first effect to appear is the reactivity of the starting derivatives for their conversion into the desired A4–A6, where the acidic conditions for the synthesis of A5 lead to the structural rearrangement to the dinuclear D5, and where the starting compound competes with A6 in the crystallization from the reaction mixture.

From a structural point of view, the six-membered Cu–N–C–C–C–N chelate ring of the propylene chain is more flexible than the five-membered Cu–N–C–C–N chelate ring when the diamine has only two carbon atoms, and hence, the copper coordination environment formed by the NNO tridentate Schiff base together with the fourth chloride anion is close to square planar in en derivatives [4] compared to tn ones. On the other hand, the displacement of the chloride anion from the N2OCu least-square plane seems to be related to the nature of G (1.24 and 0.85 Å for A5 (H) and A6 (OMe), respectively, against 1.06 and 0.68 Å for A2 (H) and A3 (OMe), respectively [4]).

The other important effect could be detected in the stability in solution, where en derivatives A1–A3 showed no alteration within 72 h in mimicked physiological conditions [4], while tn derivatives A4 and A5 might undergo the partial detachment of the coordinated amino group and opening of the six-membered metallacycle and replacement with a water molecule or phosphate anion. This probably has an impact on the biological efficiency of A4 as anticancer agents compared to A1, together with the lack of selectivity among malignant and healthy cells for both A4 and A5. In light of these results, more efforts will be devoted to the study of this class of complexes by further modifying the skeleton of the tridentate Schiff base and modulating the nature of the coordinated fourth halogenido anion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/inorganics13030094/s1: Figure S1: Infrared spectra in ATR mode for A4 and A5. Figure S2: Analysis of uptake of A5 quantified as total intracellular copper determined by AAS after 24 h treatment with 40 µmol L−1 of A5; Figure S3: Ethidium bromide (EtBr) displacement assay; Figure S4: Cleavage of pBR322 plasmid DNA (form II) by A5 after an incubation for 24 h at 37 °C.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R., D.R. and M.C.; methodology, A.F., L.G.; software, C.C.; validation, L.R. and D.R.; formal analysis, L.R. and C.C.; investigation, C.C., F.G., K.D. and P.M.; resources, L.R., A.F. and L.G.; data curation, L.R. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.R.; writing—review and editing, C.C., L.G., A.F., D.R. and M.C.; visualization, C.C. and L.R.; supervision, L.R.; project administration, L.R.; funding acquisition, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Italian Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR), and by Elettra Synchrotron (Trieste, Italy) where some single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies were conducted at the Light Laboratory beamline XRD1, through the approved proposal 20200030 entitled ‘X-ray diffraction studies on electronically and sterically modulated cytotoxic copper(II) compounds’.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

A.F. thanks Carlo Baschieri and Italo Campostrini for their support in XRD data collection at the Università degli Studi di Milano.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Rigamonti, L.; Cinti, A.; Forni, A.; Pasini, A.; Piovesana, O. Copper(II) Complexes of Tridentate Schiff Bases of 5-Substituted Salicylaldehydes and Diamines—The Role of the Substituent and the Diamine in the Formation of Mono-, Di- and Trinuclear Species—Crystal Structures and Magnetic Properties. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2008, 3633–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, L.; Forni, A.; Pievo, R.; Reedijk, J.; Pasini, A. Copper(II) Compounds with NNO Tridentate Schiff Base Ligands: Effect of Subtle Variations in Ligands on Complex Formation, Structures and Magnetic Properties. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2012, 387, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, L.; Forni, A.; Cariati, E.; Malavasi, G.; Pasini, A. Solid-State Nonlinear Optical Properties of Mononuclear Copper(II) Complexes with Chiral Tridentate and Tetradentate Schiff Base Ligands. Materials 2019, 12, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigamonti, L.; Reginato, F.; Ferrari, E.; Pigani, L.; Gigli, L.; Demitri, N.; Kopel, P.; Tesarova, B.; Heger, Z. From Solid State to in Vitro Anticancer Activity of Copper(II) Compounds with Electronically-Modulated NNO Schiff Base Ligands. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 14626–14639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, J.-P.; Dahan, F.; Fernandez Fernandez, M.B.; Fernandez Garcia, M.I.; Garcia Deibe, A.M.; Sanmartin, J. General Synthesis of ‘Salicylaldehyde Half-Unit Complexes’: Structural Determination and Use as Synthon for the Synthesis of Dimetallic or Trimetallic Complexes and of ‘Self-Assembling Ligand Complexes’. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1998, 274, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, J.-P.; Chiboub Fellah, F.Z.; Dahan, F.; Duhayon, C. Role of the Kinetic Template Effect in the Syntheses of Non Symmetric Schiff Base Complexes. Polyhedron 2013, 52, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, R.; Roncaglia, F.; Rigamonti, L. When the Metal Makes the Difference: Template Syntheses of Tridentate and Tetradentate Salen-Type Schiff Base Ligands and Related Complexes. Crystals 2021, 11, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, J.-P.; Duhayon, C.; Vendier, L. Role of the Kinetic Template Effect in the Preparation of an Original Copper Complex. Polyhedron 2018, 153, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheate, N.J.; Walker, S.; Craig, G.E.; Oun, R. The Status of Platinum Anticancer Drugs in the Clinic and in Clinical Trials. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 8113–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, R.; Moussa, Y.E.; Wheate, N.J. The Side Effects of Platinum-Based Chemotherapy Drugs: A Review for Chemists. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 6645–6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turski, M.L.; Thiele, D.J. New Roles for Copper Metabolism in Cell Proliferation, Signaling, and Disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denoyer, D.; Masaldan, S.; La Fontaine, S.; Cater, M.A. Targeting Copper in Cancer Therapy: ‘Copper That Cancer’. Metallomics 2015, 7, 1459–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, C.; Pellei, M.; Gandin, V.; Porchia, M.; Tisato, F.; Marzano, C. Advances in Copper Complexes as Anticancer Agents. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 815–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Chan, K.-Y.; Lee, H.-S.; Lin, K.N.; Wang, C.-C.; Lau, T.-S. Interplay of Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis in Cancer: Dissecting Metal-Driven Mechanisms for Therapeutic Potentials. Cancers 2024, 16, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kroemer, G. Cuproptosis: A Copper-Triggered Modality of Mitochondrial Cell Death. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Zheng, T.; Tang, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W. Recent Advances of Schiff Base Metal Complexes as Potential Anticancer Agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 525, 216327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglioli, F.; De Franco, M.; Bartoli, J.; Scaccaglia, M.; Pelosi, G.; Marzano, C.; Rogolino, D.; Gandin, V.; Carcelli, M. Anticancer Activity of New Water-Soluble Sulfonated Thiosemicarbazone Copper(II) Complexes Targeting Disulfide Isomerase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 276, 116697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaroni, A.; Riva, E.; Borghesani, V.; Donati, G.; Santoro, F.; D’Amore, V.M.; Tegoni, M.; Pelosi, G.; Buschini, A.; Rogolino, D.; et al. Synthesis and Preliminary Studies for In Vitro Biological Activity of Two New Water-Soluble Bis(Thio)Carbohydrazones and Their Copper(II) and Zinc(II) Complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Rehman, M.T.; Amir, S.; Husain, F.M.; Alsalme, A.; Siddiqui, M.A.; AlKhedhairy, A.A.; Khan, R.A. Copper(II) Complexes as Potential Anticancer and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Agents: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.K.; Nag, K. Synthesis of Phenoxo-Bridged Dicopper(II) Complexes of N-(2-Aminoalkyl)Salicylaldimines and Their Use in the Formation of Monohalogeno-Complexes and Non-Symmetrical Quadridentate Schiff-Base Complexes. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 2839–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovesana, O.; Chiari, B.; Cinti, A.; Sulpice, A. Synthesis, Structure, and Magnetic Properties of Cu2L2Cl2 (LH = N-Salicylidene-1,2-Ethanediamine)—A New S = 1/2 Spin-Liquid Candidate. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 4414–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From Visualization to Analysis, Design and Prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cingolani, A.; Zanotti, V.; Zacchini, S.; Massi, M.; Simpson, P.V.; Maheshkumar Desai, N.; Casari, I.; Falasca, M.; Rigamonti, L.; Mazzoni, R. Synthesis, Reactivity and Preliminary Biological Activity of Iron(0) Complexes with Cyclopentadienone and Amino-Appended N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands: Reactivity and Bio-Activity of Amino-Appended NHC Iron(0) Complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 33, e4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erxleben, A. Interactions of Copper Complexes with Nucleic Acids. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 360, 92–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, P.L.; Banáth, J.P. The Comet Assay: A Method to Measure DNA Damage in Individual Cells. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausi, A.; Polentarutti, M.; Onesti, S.; Plaisier, J.R.; Busetto, E.; Bais, G.; Barba, L.; Cassetta, A.; Campi, G.; Lamba, D.; et al. Status of the Crystallography Beamlines at Elettra. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2015, 130, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabsch, W. XDS . Acta Crystallogr. B 2010, 66, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An Update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, M.A.M.; Michalkova, H.; Jimenez, A.M.J.; Petrlak, F.; Do, T.; Sivak, L.; Haddad, Y.; Kubickova, P.; De Los Rios, V.; Casal, J.I.; et al. Metallothionein-3 Is a Multifunctional Driver That Modulates the Development of Sorafenib-Resistant Phenotype in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).