Exploring Customer Journeys in the Context of Dentistry: A Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Organisational Context

3. The Customer Persona

4. Contemporary Customer Purchase Decision-Making Models

5. Marketing Approaches

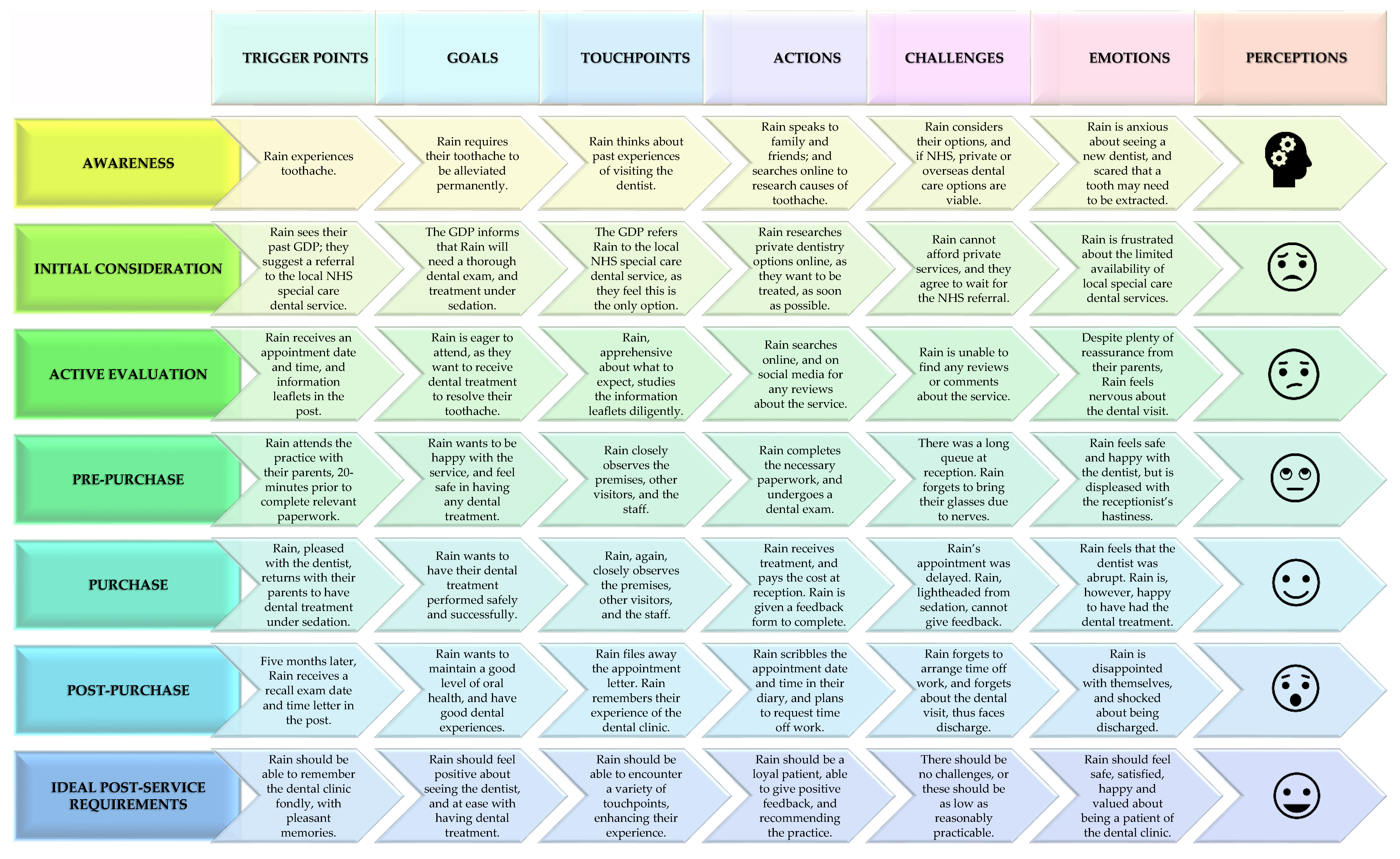

6. The Customer Journey Map

6.1. Awareness Stage

6.2. Initial Consideration Stage

6.3. Active Evaluation Stage

6.4. Pre-Purchase Stage

6.5. Purchase Stage

6.6. Post-Purchase Stage

7. Discussion

7.1. Customer (Patient) Journeys in Private Dental Practice

7.2. The Special Care Dentistry Sector

7.3. Removing Digital Exclusion

7.4. Using Ethical Marketing

7.5. Achieving Customer (Patient)-Centricity

7.6. Recommendations for Improving the Customer (Patient) Journey with Digitalisation

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Health Is a Fundamental Human Right. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/health-is-a-fundamental-human-right (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Jabbal, J.; Lewis, M. Approaches to Better Value in the NHS: Improving Quality and Cost; King’s Fund: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Torpie, K. Customer service vs. patient care. Patient Exp. J. 2014, 1, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevell, M.I. What do we call ‘them’?: The ‘patient’ versus ‘client’ dichotomy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 51, 770–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, H. What’s in a name: ‘client’, ‘patient’, ‘customer’, ‘consumer’, ‘expert by experience’, ‘service user’—What’s next? Br. J. Soc. Work 2009, 39, 1101–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grace, M. Customers or patients? Br. Dent. J. 2003, 194, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, D.S.J.; Mercieca-Bebber, R.; Tesson, S.; Seidler, Z.; Lopez, A.L. Patient, client, consumer, survivor or other alternatives? A scoping review of preferred terms for labelling individuals who access healthcare across settings. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyatt, A.T. Patients not customers. Br. Dent. J. 2003, 194, 584–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drynan, R. Improving the customer experience. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudak, P.L.; McKeever, P.; Wright, J.G. The metaphor of patients as customers: Implications for measuring satisfaction. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2003, 56, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Miller, N.H.; Rizzo, J.; Zeckhauser, R. Demanding customers: Consumerist patients and quality of care. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2011, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halvorsrud, R.; Kvale, K.; Følstad, A. Improving service quality through customer journey analysis. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2016, 26, 840–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ponsignon, F.; Smart, A.; Phillips, L. A customer journey perspective on service delivery system design: Insights from healthcare. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 2328–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.; Kong, X. The customer experience: A road-map for improvement. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2011, 21, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sisodia, R.S.; Sharma, A. The antecedents and consequences of customer-centric marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Services Commissioning Board. Securing Excellence in Commissioning NHS Dental Services; NHSCB: Leeds, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, M.; Calnan, M.; Manley, G. Private or NHS General Dental Service care in the United Kingdom? A study of public perceptions and experiences. J. Public Health Med. 1999, 21, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, R.; Patel, D.; Pennycate, R. The Economics of Dental Care; Office of Health Economics: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, M. Private versus NHS? Br. Dent. J. 1998, 184, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Anthony, S.D.; Berstell, G.; Nitterhouse, D. Finding the right job for your product. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2007, 48, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Herskovitz, S.; Crystal, M. The essential brand persona: Storytelling and branding. J. Bus. Strategy 2010, 31, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Kanuk, L.L. Consumer Behavior; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Belch, G.E.; Belch, M.A. Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cetină, I.; Munthiu, M.C.; Rădulescu, V. Psychological and social factors that influence online consumer behavior. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 62, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, A.; Granbois, D.; Summers, J. Planning, search, certainty and satisfaction among durables buyers: A longitudinal study. Adv. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 394–399. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing; Pearson: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Court, D.; Elzinga, D.; Mulder, S.; Vetvik, O.J. The consumer decision journey. McKinsey Q. 2009, 3, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- American Marketing Association. What Is Marketing?—The Definition of Marketing. 2017. Available online: https://www.ama.org/the-definition-of-marketing-what-is-marketing (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- American Marketing Association. Advertising Archives. 2019. Available online: https://www.ama.org/topics/advertising (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Raeisi, S.; Lingjie, M.; Suhaili Binti Ramli, N. A hierarchical model of mediation effect of motivation (MO) between internal marketing (IM) and service innovation (SI). Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashford, R.; Blinkhorn, A.S. Marketing dental care to the reluctant patient. Br. Dent. J. 1999, 186, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, P.K.; Rafiq, M.; Saad, N.M. Internal marketing and the mediating role of organisational competencies. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Kannan, P.K.; Inman, J.J. From multi-channel retailing to omni-channel retailing: Introduction to the special issue on multi-channel retailing. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffey, D.; Ellis-Chadwick, F. Digital Marketing; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Følstad, A.; Kvale, K. Customer journeys: A systematic literature review. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2018, 28, 196–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diana, C.; Pacenti, E.; Tassi, R. Visualtiles: Communication Tools for (Service) Design. In Proceedings of the ServDes 2009, Oslo, Norway, 24–26 November 2009; Linköping University Electronic Press: Linköping, Sweden, 2012; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Crosier, A.; Handford, A. Customer journey mapping as an advocacy tool for disabled people: A case study. Soc. Mar. Quart. 2012, 18, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, J.T.; Simionato, E.M.; Peres, K.G.; Peres, M.A.; Traebert, J.; Marcenes, W. Dental pain as the reason for visiting a dentist in a Brazilian adult population. Rev. Saude Publica 2004, 38, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichner, T.; Gruber, B. Managing customer touchpoints and customer satisfaction in b2b mass customization: A case study. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2017, 8, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Oral Health Foundation. “More Money Needs to Be Invested in NHS Dentistry,” Charity Demands and the Public Agree. 2018. Available online: https://www.dentalhealth.org/news/more-money-needs-to-be-invested-in-nhs-dentistry-charity-demands-and-research-shows-the-public-agree (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Westgarth, D. How much longer does NHS dentistry have left? BDJ Pract. 2020, 33, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, M.G.; Djemal, S.; Lewis, N. Ethical marketing in ‘aesthetic’ (‘esthetic’) or ‘cosmetic dentistry’ part 3. Dent. Update 2012, 39, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Dental Journal. Celebrity endorsements: Are they worth the money? Br. Dent. J. 2018, 225, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, L. Implementing a treatment coordinator in your practice. Dent. Nurs. 2010, 6, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, K. Flexible payment plans launched. Br. Dent. J. 2018, 224, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A.C.; Adam, L.; Thomson, W.M. Dentists’ perspectives on commercial practices in private dentistry. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2022, 7, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, D. Where are all the specialists? BDJ Pract. 2020, 33, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, B.J. Issues and challenges in special care dentistry. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 69, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K.; Ornes, L.L.; Paulson, P. Engaging patients through your website. J. Healthc. Qual. 2014, 36, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, A.T.; Galak, J. The effects of traditional and social earned media on sales: A study of a microlending marketplace. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jampani, N.D.; Nutalapati, R.; Dontula, B.S.; Boyapati, R. Applications of teledentistry: A literature review and update. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2011, 1, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, L.; Stamp, E.; Smith, J.; Kelly, H.; Parker, N.; Stockwell, K.; Aluko, P.; Othman, M.; Brittain, K.; Vale, L. Internet delivery of intensive speech and language therapy for children with cerebral palsy: A pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England. Guides for Commissioning Dental Specialties–Special Care Dentistry; NHS England: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Porritt, J.; Baker, S.R.; Marshman, Z. A service evaluation of patient pathways and care experiences of dentally anxious adult patients. Community Dent. Health 2012, 29, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castle-Clarke, S.; Imison, C. The Digital Patient: Transforming Primary Care; Nuffield Trust: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Olphert, W.; Damodaran, L. Older people and digital disengagement: A fourth digital divide? Gerontology 2013, 59, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lagu, T.; Hannon, N.S.; Rothberg, M.B.; Lindenauer, P.K. Patients’ evaluations of health care providers in the era of social networking: An analysis of physician-rating websites. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 942–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berman, B.; Thelen, S. Planning and implementing an effective omnichannel marketing program. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsrud, R.; Lillegaard, A.L.; Røhne, M.; Jensen, A.M. Managing complex patient journeys in healthcare. In Service Design and Service Thinking in Healthcare and Hospital Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert, B.; Bleecker, T.; Saub, E. Dentists and the patients who love them: Professional and patient views of dentistry. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1994, 125, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.M.; Huggins, T.J. Empathy in the dentist-patient relationship: Review and application. N. Z. Dent. J. 2014, 110, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht, R.; Struppek, J.; Heydecke, G.; Reissmann, D.R. Patients’ criteria for choosing a dentist: Comparison between a university-based setting and private dental practices. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Dental Council. Standards for the Dental Team; General Dental Council: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- General Dental Council. Standards for Dental Professionals; General Dental Council: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dable, R.A.; Prasanth, M.A.; Singh, S.B.; Nazirkar, G.S. Is advertising ethical for dentists? An insight into the Indian scenario. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2011, 3, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henríquez-Tejo, R.B.; Cartes-Velásquez, R.A. Patients’ perceptions about dentists: A literature review. Odontoestomatología 2016, 18, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- de Lira, A.D.; Magalhães, B.M. Digital marketing in dentistry and ethical implications. Braz. Dent. Sci. 2018, 21, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolinsky, H.R.; Helbig, N. Risky business: Applying ethical standards to social media use with vulnerable populations. Adv. Soc. Work 2015, 16, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bloom, G.; Standing, H.; Lloyd, R. Markets, information asymmetry and health care: Towards new social contracts. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 2076–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Dental Council. Guidance on Advertising; General Dental Council: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Advertising Standards Authority. ASA Annual Report 2011. 2011. Available online: https://www.asa.org.uk/news/asa-annual-report-2011.html (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Bitner, M.J.; Gremler, D.D. Services Marketing: Integrating Customer Focus across the Firm; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Buvat, J.; Solis, B.; Crummenerl, C.; Aboud, C.; Kar, K.; El Aoufi, H.; Sengupta, A. The Digital Culture Challenge: Closing the Employee-Leadership Gap; Capgemini Digital Transformation Institute Survey; Capgemini Digital Transformation Institute: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, B. Patients’ access to their electronic record: Offer patients access as soon as you can. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e423–e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, S.; Kaplan, S.; Ware, J.E., Jr. Expanding patient involvement in care: Effects on patient outcomes. Ann. Intern. Med. 1985, 102, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bughin, J.; van Zeebroeck, N. New evidence for the power of digital platforms. McKinsey Q. 2017, 15, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Software of Excellence. Online Reputation Manager. 2020. Available online: https://softwareofexcellence.co.uk/solutions/online-reputation-manager/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Estai, M.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M. Optimizing patient referrals to dental consultants: Implication of teledentistry in rural settings. Australas. Med. J. 2016, 9, 249–252. [Google Scholar]

- Software of Excellence. Patient Experience. 2020. Available online: https://softwareofexcellence.co.uk/patient-experience/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Nanaprasagam, A.; Maddock, N.; McIver, A.; Smyth, C.; Walshaw, M.J. S76 “Straight to CT” in Primary Care—Improving the Lung Cancer Patient Journey. Thorax 2015, 70, A45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fallis, J. Touch the screen now to see a doctor. CMAJ 2012, 184, E339–E340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coyle, N.; Kennedy, A.; Schull, M.J.; Kiss, A.; Hefferon, D.; Sinclair, P.; Alsharafi, Z. The use of a self-check-in kiosk for early patient identification and queuing in the emergency department. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 21, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Software of Excellence. Contactless Patient Journeys at Your Clinics. 2020. Available online: https://softwareofexcellence.co.uk/contactless-patient-journey/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Berkhout, C.; Zgorska-Meynard-Moussa, S.; Willefert-Bouche, A.; Favre, J.; Peremans, L.; Van Royen, P. Audiovisual aids in primary healthcare settings’ waiting rooms. A systematic review. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.P.; Elliott, K.; Gall, J.; Woodward-Kron, R. Patient and clinician engagement with health information in the primary care waiting room: A mixed methods case study. J. Public Health Res. 2019, 8, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kravitz, N.D.; Bowman, S.J. A paradigm shift in orthodontic marketing. Semin. Orthod. 2016, 22, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, R.; Poston, I. Measurement of the effects of an integrated, point-of-care computer system on quality of nursing documentation and patient satisfaction. Comput. Nurs. 2000, 18, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- St John, E.; Askari, A.; Fenn, D.; Saleh, M.; Keogh, G.; Pisarek, C.; Rimmer, S.; Lion, P.; Darzi, A.; Leff, D. Digital procedure specific consent forms (OpInform) compared to handwritten surgical consent forms in breast surgery. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 43, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, F.; Gandolfi, A.; Luongo, G.; Logozzo, S. Intraoral scanners in dentistry: A review of the current literature. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Software of Excellence. Automated Recalls. 2020. Available online: https://softwareofexcellence.co.uk/solutions/automated-recalls/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Khasawneh, A.; Ponathil, A.; Firat Ozkan, N.; Chalil Madathil, K. How should I choose my dentist? A preliminary study investigating the effectiveness of decision aids on healthcare online review portals. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1–5 October 2018; Volume 62, pp. 1694–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.W.; Shaffer, J.; Ye, S.; Falzon, L.; Emeruwa, I.O.; Sundquist, K.; Inneh, I.A.; Mascitelli, S.L.; Manzano, W.M.; Vawdrey, D.K.; et al. Interventions to improve hospital patient satisfaction with healthcare providers and systems: A systematic review. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NHS Dental Services | Private Dental Services | |

|---|---|---|

| Scheduling of appointments |

|

|

| Attendance patterns |

|

|

| Affordability of treatment |

|

|

| Ethos of treatment |

|

|

| Availability of specialist treatment |

|

|

| Equipment, materials, and technology |

|

|

| Source of funding |

|

|

| Customer (Patient): Rain, 25-Year-Old, Newly Qualified Veterinarian | |

|---|---|

| Reason for referral |

|

| Social history |

|

| Usage of marketing channels |

|

| Motivation |

|

| Stage | Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Ease for customer (patient) discovery |

|

| 2. Booking an appointment |

|

| 3. Before an appointment |

|

| 4. Arrival at the dental practice for an appointment |

|

| 5. Waiting room |

|

| 6. With the dentist |

|

| 7. Leaving the practice |

|

| 8. Feedback |

|

| 9. Follow-up |

|

| 10. Returning |

|

| 11. Auditing |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Modha, B. Exploring Customer Journeys in the Context of Dentistry: A Case Study. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030075

Modha B. Exploring Customer Journeys in the Context of Dentistry: A Case Study. Dentistry Journal. 2023; 11(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030075

Chicago/Turabian StyleModha, Bhaven. 2023. "Exploring Customer Journeys in the Context of Dentistry: A Case Study" Dentistry Journal 11, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030075

APA StyleModha, B. (2023). Exploring Customer Journeys in the Context of Dentistry: A Case Study. Dentistry Journal, 11(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030075