Does Preferred Information Format Affect Consumers’ Willingness to Pay: A Case Study of Orange Juice Produced by Biotechnology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review

3. Material and Methods

Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

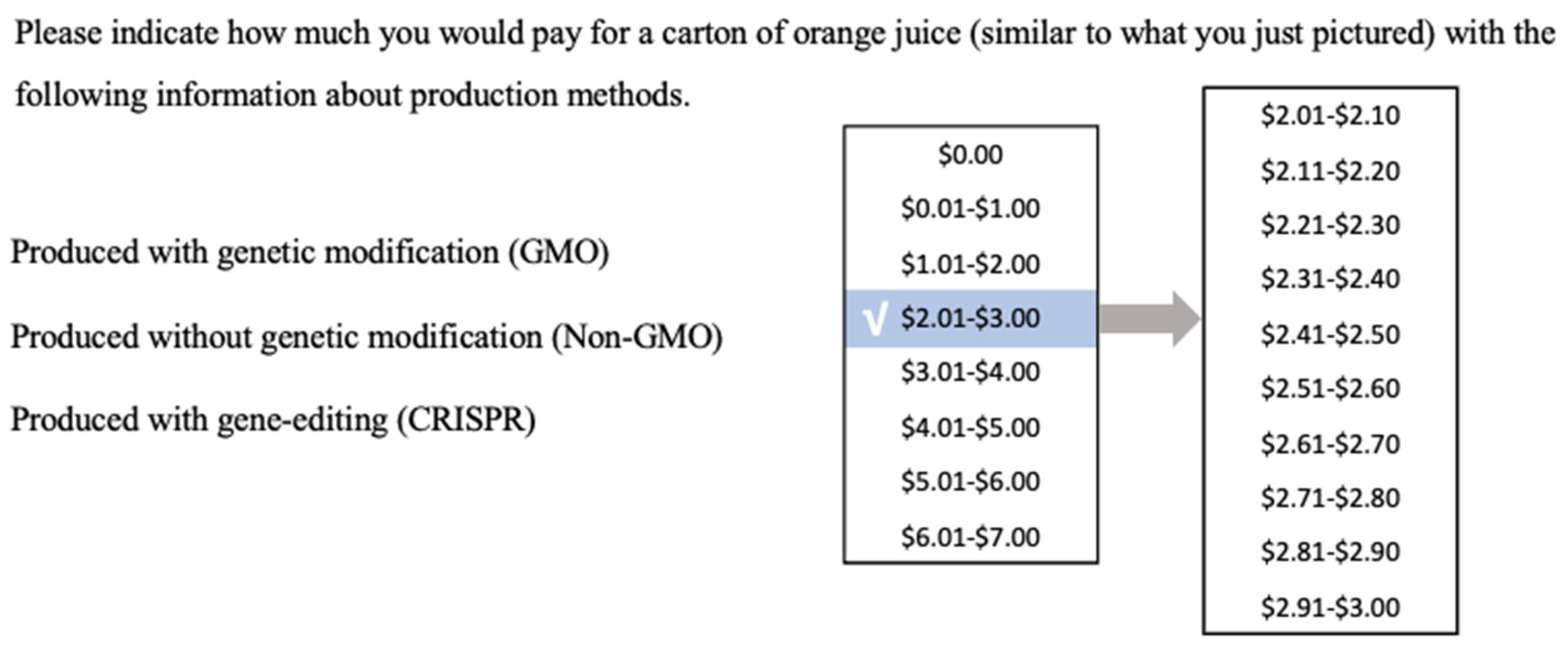

Appendix A.1. Information Treatment

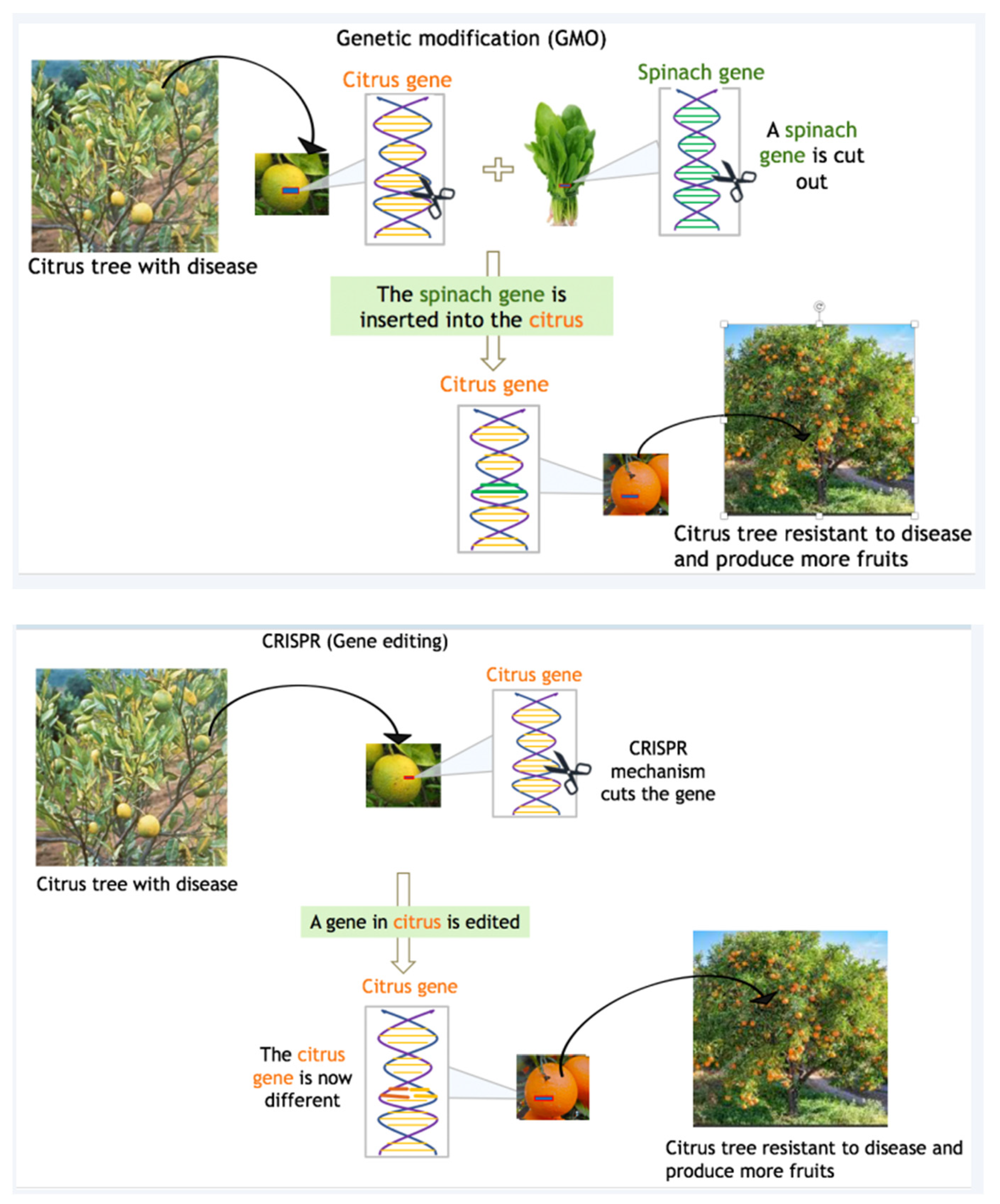

- Genetic modification, or GM, is a way to improve crop varieties. GM involves adding a gene from one species into a different species, giving it new or different characteristics. The new gene becomes part of the GM plant. For example, a gene from spinach could be inserted into a fruit plant to help the fruit plant resist a disease and produce more fruit.

- Gene-editing, such as CRISPR, is a way to improve crop varieties. CRISPR works like a word-processor to edit the text of the DNA instruction manual to improve the directions the plant receives. CRISPR can accurately target a specific part within a gene to be altered, causing a break in the DNA and using the cell’s natural repair machinery to introduce changes, similar to a search and replace when editing text. For example, the genes of a fruit could be edited to produce a fruit plant that can resist a disease and produce more fruit.

Appendix A.2

Appendix B

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am interested in the information about biotechnology that I saw earlier in the survey | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I trust the information about biotechnology that I saw earlier in this survey | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Do you think the method of delivering information (such as a written description, images, and videos) affects the trustworthiness of the information about biotechnology? | |||||

| ○ Yes (1) ○ No (2) | |||||

| How trustworthy did you find the information in each description? | |||||

| Not at all Trustworthy | A little Trustworthy | Neutral | Trustworthy | Very Trustworthy | |

| Written description | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Images/Visual description | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Video | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

References

- Appel, G.; Grewal, L.; Hadi, R.; Stephen, A.T. The future of social media in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 48, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; House, L.A.; Gao, Z. How do consumers respond to labels for crispr (gene-editing)? Food Policy 2022, 112, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashler, H.; McDaniel, M.; Rohrer, D.; Bjork, R. Learning Styles. Psychol. Sci. Public Interes. 2008, 9, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massa, L.J.; Mayer, R.E. Testing the ATI hypothesis: Should multimedia instruction accommodate verbalizer-visualizer cognitive style? Learn. Individ. Differ. 2006, 16, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerjets, P.; Scheiter, K. Goal Configurations and Processing Strategies as Moderators between Instructional Design and Cognitive Load: Evidence From Hypertext-Based Instruction. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 38, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanani, U.; Shapira, B.; Shoval, P. Information Filtering: Overview of Issues, Research and Systems. User Model. User-Adapted Interact. 2001, 11, 203–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. When does web-based personalization really work? The distinction between actual personalization and perceived personalization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimer, B.K.; Kreuter, M.W. Advancing Tailored Health Communication: A Persuasion and Message Effects Perspective. J. Commun. 2006, 56, S184–S201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, S.; Sundar, S.S. The psychological appeal of personalized content in web portals: Does customization affect attitudes and behavior? J. Commun. 2006, 56, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.Y.; Ho, S.Y. Web Personalization as a Persuasion Strategy: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globus, R.; Qimron, U. A technological and regulatory outlook on CRISPR crop editing. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 119, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, F.; Onyango, B.; Schilling, B.; Hallman, W.; Adelaja, A. Product attributes, consumer benefits and public approval of genetically modified foods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2003, 27, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Moore, M.; House, L.O.; Morrow, B. Influence of brand name and type of modification on consumer acceptance of genetically engineered corn chips: A preliminary analysis. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2002, 4, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; McCluskey, J.J.; Wahl, T.I. Effects of Information on Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for GM-Corn-Fed Beef. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2004, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, F.; Fox, J.A.S.; Mullins, E.; Wallace, M. Consumer Willingness-to-Pay for Genetically Modified Potatoes in Ireland: An Experimental Auction Approach. Agribusiness 2017, 33, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hffman, W.E.; Rousu, M.; Shogren, J.F.; Tegene, A. Consumer’s resistance to genetically modified foods: The role of information in an uncertain environment. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2004, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shew, A.M.; Nalley, L.L.; Snell, H.A.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Dixon, B.L. CRISPR versus GMOs: Public acceptance and valuation. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 19, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenbrandt, A.K.; House, L.A.; Gao, Z.; Olmstead, M.; Gray, D. Consumer acceptance of cisgenic food and the impact of information and status quo. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 69, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, L.J.; Scholderer, J.; Bredahl, L. Communicating about the Risks and Benefits of Genetically Modified Foods: The Mediating Role of Trust. Risk Anal. 2003, 23, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Veeman, M.M.; Adamowicz, W.L. Functional food choices: Impacts of trust and health control beliefs on Canadian consumers’ choices of canola oil. Food Policy 2015, 52, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y. Correlates of Consumer Trust in Online Health Information: Findings from the Health Information National Trends Survey. J. Health Commun. 2011, 16, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainley, M.; Hidi, S.; Berndorff, D. Interest, learning, and the psychological processes that mediate their relationship. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, R.L.; Annetta, L.; Meldrum, J.; Vallett, D. Measuring science interest: Rasch validation of the science interest survey. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2011, 10, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-Dependent Model. Q. J. Econ. 1991, 106, 1039–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupey, E. Restructuring: Constructive Processing of Information Displays in Consumer Choice. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Mental Imagery and Memory: Coding Ability or Coding Preference. J. Ment. Imag. 1978, 2, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Childers, T.L.; Houston, M.J.; Heckler, S.E. Measurement of individual differences in visual versus verbal information processing. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojka, J.Z.; Giese, J.L. The Influence of Personality Traits on the Processing of Visual and Verbal Information. Mark. Lett. 2001, 12, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E.; Massa, L.J. Three Facets of Visual and Verbal Learners: Cognitive Ability, Cognitive Style, and Learning Preference. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollöffel, B. Exploring the relation between visualizer–verbalizer cognitive styles and performance with visual or verbal learning material. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, C.; Reichelt, M.; Zander, S. The effect of the personalization principle on multimedia learning: The role of student individual interests as a predictor. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyzberg, D.; Ramachandran, A.; Scassellati, B. The Effect of Personalization in Longer-Term Robot Tutoring. ACM Trans. Human-Robot Interact. 2018, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, S. The accessibility of university web sites: The case of Turkish universities. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2011, 10, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, M.; Kämmerer, F.; Niegemann, H.M.; Zander, S. Talk to me personally: Personalization of language style in computer-based learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hobbs, J.E. The Power of Stories: Narratives and Information Framing Effects in Science Communication. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 102, 1271–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjesivac, I.; Hayslett, M.A.; Binford, M.T. To Eat or Not to Eat: Framing of GMOs in American Media and Its Effects on Attitudes and Behaviors. Sci. Commun. 2020, 42, 747–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, B.R.; Anderton, B.N.; Davidson, K.A.; Bernard, J.C. The effect of scientific information and narrative on preferences for possible gene-edited solutions for citrus greening. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 1595–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.T.; Hallman, W.K. Who Does the Public Trust? The Case of Genetically Modified Food in the United States. Risk Anal. 2005, 25, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A. Willingness-to-pay for sustainability-labelled chocolate: An experimental auction approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, N.; Olson, J.S.; Gergle, D.; Olson, G.M.; Wright, Z. Effects of four computer-mediated communications channels on trust development. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI: ACM Special Interest Group on Computer–Human Interaction; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.S.; House, L.A.; Gao, Z. Respondent screening and revealed preference axioms: Testing quarantining methods for enhanced data quality in web panel surveys. Public Opin. Q. 2015, 79, 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.J.; Solow, R.; Leamer, E.; Portney, P.; Radner, R.; Schuman, H. Report of the NOAA panel on contingent valuation. Fed. Regist. 1993, 58, 4601–4614. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Woods, T.; Bastin, S.; Cox, L.; You, W. Assessing Consumer Willingness to Pay for Value-Added Blueberry Products Using a Payment Card Survey. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2011, 43, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Gao, Z.; Zeng, Y. Willingness to pay for the “Green Food” in China. Food Policy 2014, 45, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; Gao, Z.; Anderson, J.L.; Love, D.C. Consumers’ willingness to pay for information transparency at casual and fine dining restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, G.; Bauer, M.; Durant, J.; Allum, N.C. Words Apart? The reception of genetically modified foods in Europe and the U.S. Science 1999, 285, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschner, P.A.; van Merrinboer, J.J.G. Do Learners Really Know Best? Urban Legends in Education. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 48, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Treatment Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 43.1% | 40% |

| College degree and above | 78.4% | 76.8% |

| Annual Household Income | ||

| Income < 14,999 | 10.8% | 9.1% |

| Income USD 15,000–24,999 | 10.3% | 12.6% |

| Income USD 25,000–34,999 | 11.8% | 13.1% |

| Income USD 35,000–49,999 | 13.2% | 18% |

| Income USD 50,000–74,999 | 21.1% | 17.8% |

| Income USD 75,000–99,999 | 13.2% | 13.8% |

| Income USD 100,000–149,999 | 12.8% | 11.1% |

| Income USD 150,000–199,999 | 5.4% | 2.5% |

| Income USD 200,000+ | 1.5% | 2.0% |

| Knowledge of GM | 5.0 | 4.9 |

| Knowledge of CRISPR | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Percentage of respondents correctly answer | 61.7% | 63.7% |

| After receiving information in one format (First Stage) | ||

| Interest in the information | 3.61 | 3.72 |

| Trust in the information | 3.64 | 3.58 |

| After receiving information in all formats (Second Stage) | ||

| Information format affect credibility | 69.6% | 67.4% |

| Trust in the information by word | 3.57 | 3.62 |

| Trust in the information by infographic | 3.68 | 3.66 |

| Trust in the information by video | 3.79 | 3.75 |

| Respondents’ preference for each information format | ||

| Word | 40% | |

| Infographic | 39% | |

| Video | 21% | |

| Variable | Model 1 Changing WTP for Non-GM OJ | Model 2 Changing WTP for GM OJ | Model 3 Changing WTP for CRISPR OJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre_WTP_NonGM | NA | 0.09 ** | 0.10 ** |

| Pre_WTP_GM | 0.09 ** | NA | −0.24 **** |

| Pre_WTP_CRISPR | −0.11 *** | −0.17 **** | NA |

| OneFormat | 0.19 ** | −0.15 | −0.02 |

| Infographics | 0.17 * | 0.02 | 0.33 ** |

| Video | −0.00 | −0.08 | 0.14 |

| GM Knowledge | 0.03 | 0.06 ** | 0.05 |

| CRISPR Knowledge | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.03 |

| Trust | −0.06 | 0.17 *** | 0.11 * |

| Interest | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.09 |

| Variable | Word | Infographics | Video | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Marginal Effect | Coefficient | Marginal Effect | Coefficient | Marginal Effect | |

| Gender | −0.60 *** | −0.12 *** | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.71 *** | 0.11 *** |

| No kids | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.04 | −0.63 *** | −0.10 *** |

| Age range 25–34 | −0.12 | −0.03 | −0.22 | −0.05 | 0.46 | 0.07 |

| Age range 35–44 | 0.32 | 0.07 | −0.26 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Age range 45–54 | 0.60 * | 0.12 * | −0.69 ** | −0.15 ** | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| Age range 55–64 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.54 | −0.12 | 0.74 | 0.12 |

| Age range 65+ | 0.33 | 0.07 | −0.26 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.01 |

| Student | −1.36 * | −0.28 * | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.07 |

| Retired | 0.98 *** | 0.20 *** | −0.86 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.36 | −0.06 |

| Other employment | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| Gardening | 0.12 * | 0.03 * | −0.16 ** | −0.03 ** | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Following celebrities | −0.23 ** | −0.05 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.05 ** | −0.01 | −0.00 |

| Frequency party | 0.23 *** | 0.05 *** | −0.18 ** | −0.04 ** | −0.06 | −0.01 |

| Living in suburban areas | −0.42 ** | −0.09 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.11 ** | −0.16 | −0.03 |

| Living in rural areas | −0.20 | −0.04 | 0.48 * | 0.10 * | −0.42 | −0.07 |

| Income USD 15,000–24,999 | −0.30 | −0.06 | 0.43 | 0.09 | −0.19 | −0.03 |

| Income USD 25,000–34,999 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.83 ** | 0.18 ** | −1.18 ** | −0.18 ** |

| Income USD 35,000–49,999 | −0.18 | −0.04 | 0.58 | 0.13 | −0.53 | −0.08 |

| Income USD 50,000–74,999 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.53 | 0.11 | −0.50 | −0.08 |

| Income USD 75,000–99,999 | −0.57 | −0.12 | 0.88 ** | 0.18 ** | −0.42 | −0.07 |

| Income USD 100,000–149,999 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.12 | −0.99 ** | −0.16 ** |

| Income USD 150,000–199,999 | −0.50 | −0.10 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Income USD 200,000+ | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.14 | −0.86 | −0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, Y.; House, L.A.; Gao, Z. Does Preferred Information Format Affect Consumers’ Willingness to Pay: A Case Study of Orange Juice Produced by Biotechnology. Foods 2023, 12, 2130. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12112130

Hu Y, House LA, Gao Z. Does Preferred Information Format Affect Consumers’ Willingness to Pay: A Case Study of Orange Juice Produced by Biotechnology. Foods. 2023; 12(11):2130. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12112130

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Yang, Lisa A. House, and Zhifeng Gao. 2023. "Does Preferred Information Format Affect Consumers’ Willingness to Pay: A Case Study of Orange Juice Produced by Biotechnology" Foods 12, no. 11: 2130. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12112130

APA StyleHu, Y., House, L. A., & Gao, Z. (2023). Does Preferred Information Format Affect Consumers’ Willingness to Pay: A Case Study of Orange Juice Produced by Biotechnology. Foods, 12(11), 2130. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12112130