Polish-Lithuanian Border Cuisine as an Idea for the Promotion and Expansion of the Region’s Tourist Attractiveness

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Attractiveness of regional dishes, their appearance, flavour and smell affect consumers’ purchasing decisions, which contributes to the promotion of Polish-Lithuanian border regions by clearly emphasising their originality and distinctiveness;

- Some traditional dishes offered by Polish-Lithuanian cuisine constitute the region’s tourist attraction, and, as such, they affect the region’s promotion, which results in increasing tourist arrivals in these areas of Poland and Lithuania;

- Culinary tourism provides social, cultural and economic benefits to locals.

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Population and Research Procedure

3.2. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Durydiwka, M. Turystyka kulinarna–nowy trend w turystyce kulturowej. Pr. Stud. Geogr. 2013, 52, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Laudan, R. Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mikos von Rohrscheidt, A. Turystyka Kulturowa. Fenomen, Potencjał, Perspektywy. 2008. Available online: https://depot.ceon.pl/handle/123456789/18813 (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Žuromskaite, B. Development of culinary tourism in Lithuania. Tur. Kult. 2009, 12, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, A.; Plesoianu, D. Comparison regarding the tourism impact on the economy of Bulgaria and Romania. Scientific Papers. Series Management. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2019, 19, 395–408. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H.; Packer, J.; Scott, N. Travel lifestyle preferences and destination activity choices of Slow Food members and nonmembers. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulcheva, I. Analysis of the state of culinary tourism in Bulgaria. Scientific Papers: Management. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2020, 20, 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Carpio, N.M.; Napod, W.; Do, H.W. Gastronomy as a factor of tourists’ overall experience: A study of Jeonju, South Korea. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2021, 35, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2022. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/dane/podgrup/tablica (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwil, I. Szlak Kulinarny Smaki Dolnego Śląska. J. Tour. Reg. Dev. 2018, 10, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete-Alcocer, N.; Hernandez-Rojas, R.D. Does local cuisine influence the image of a World Heritage destination and sub-sequent loyalty to that destination? Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyantaria, N.L.P.; Budhia, M.K.S.; Utamaa, I.M.S.; Yasa, I.G.W.M. Management of Culinary Tourism Based on Community Participation to Improve Community Welfare. Turk. Online J. Qual. Inq. 2021, 12, 781–793. [Google Scholar]

- Daugstad, K.; Kirchengast, C. Authenticity and the pseudo-backstage of agri-tourism. J. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J.; Hill, R. Expressing Sense of Place and Terroir through Wine to Tourism Encounters: Antipodal Reflections from France to New Zealand. In The Routledge Handbook of Wine and Culture; Unwin, T., Charters, S., Dutton, J., Harding, G., Smith Maguire, J., Marks, D., Demossier, M., Eds.; Routledge Handbooks: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Okumus, B.; Wang, C.H.; Chiu, C.Y. Food tourism: Cooking holiday experiences in East Asia. Tour. Rev. 2020, 5, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Rojas, R.D.; Folgado-Fernandez, J.A.; Palos-Sanchez, P.R. Influence of the restaurant brand and gastronomy on tourist loyalty. A study in Córdoba (Spain). Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 23, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T.S.; Wang, Y.C. Experiential value in branding food tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. (Eds.) Food Tourism and Regional Development: Networks, Products and Trajectories; Routledge: Londin, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, T.D.; Mossberg, L.; Therkelsen, A. Food and tourism synergies: Perspectives on consumption, production and destination development. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, C. Food and gastronomy for sustainable place development: A multidisciplinary analysis of different theoretical approaches. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováčková, D.; Paškrtová, L.; Vnuková, J. Cross-Border Provision of Services: Case Study in the Slovak Republic. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J. Tourists, local food and the intention-behaviour gap. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frash, R.E.; Di Pietro, R.; Smith, W. Pay more for McLocal? Examining motivators for willingness to pay for local food in a chain restaurant setting. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, Ö.C.; Gürbüz, A. The effect of local food consumption of domestic tourists on sustainable tourism. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caber, M.; Yilmaz, G.; Kiliçarslan, D.; Öztürk, A. The effects of tour guide performance and food involvement on food neophobia and local food consumption intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1472–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvoll, S.; Forbord, M.; Blekesaune, A. An empirical investigation of tourists’ consumption of local food in rural tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 16, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.F.; Triana, M.F. Las rutas gastronómicas en el departamento de Meta: Una propuesta de sustentabilidad turística. Tur. Soc. 2019, 25, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.; Yin, S.; Liu, Y. The Development of Traditional Food in Tourist Destinations from the Perspective of Dramaturgy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrysiak, T. Wiejska Turystyka Kulturowa; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gulbicka, B. Żywność Tradycyjna i Regionalna w Polsce; Instytut Ekonomiki Rolnictwa i Gospodarki Żywnościowej: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, L.; Guardia, M.D.; Xicola, J.; Verbeke, W.; Vanhonacker, F.; Zakowska-Biemans, S.; Sajdakowska, M.; Sulmont-Rosse, C.; Issanchou, S.; Contel, M.; et al. Consumer-driven Definition of Traditional Food Products and Innovation in Traditional Foods. A Qualitative Cross-cultural Study. Appetite 2009, 52, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warmińska, M.; Dąbrowska, A.; Mozolewski, W. Produkty regionalne narzędziem promocji turystyki na obszarach wiejskich województwa pomorskiego. Barom. Reg. 2012, 4, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenjuk, B.; Đerčan, B.; Tešenović, D. Gastronomy tourism as a factor of regional development. Ekonomika 2012, 58, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Strenik, A. Produkty Tradycyjne i Regionalne Szansą na Rozwój Twojej Gminy; Departament Rolnictwa i Modernizacji Terenów Wiejskich: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grubor, B.; Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Derčan, B.; Tešanović, D.; Banjac, M.; Lukić, T.; Živković, M.B.; Udovičić, D.I.; Šmugović, S.; Ivanović, V.; et al. Traditional and Authentic Food of Ethnic Groups of Vojvodina (Northern Serbia)—Preservation and Potential for Tourism Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.; Pham, D.; Eves, A.; Wang, X.L. Understanding tourists’ consumption emotions in street food experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 392–403. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, M.; Darabaneanu, D.; Chirodea, F.; Toca, C. Analysis of Social Support as an Argument for the Sustainable Construction of the European Community Space. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacionalinė Turizmo Plėtros Programa; Keliauk Lietuvoje: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2019.

- Imbrasienė, B. Lietuvių Kulinarijos Paveldas; Baltos Iankos: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Biaspamiatnych, M.I. Regional identities in contemporary eastern Europe: Belarusian-Polish-Lithuanian borderlands: Phenomenological Analysis. Limes Cult. Reg. 2008, 1, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuścińska, M. Kuchnia Pogranicza Polsko-Litewskiego; Warmińsko-Mazurski Ośrodek Doradztwa Rolniczego: Olsztyn, Poland, 2018; Volume 6–7, pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, A. National identity: The process of the construction of the national identities on the Polish-Lithuanian-Belarusian borderland. Limes Cult. Reg. 2008, 1, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meškelevičienė, L.M. Muziejai ir kultūrinis turizmas tarptautinės bendruomenės akiratyje. Liet. Muz. 2003, 2, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Omieciuch, J. Edukacyjna rola turystyki kulinarnej na przykładzie szlaki turystycznego Wielki Gościniec Litewski. In Edukacyjna Rola Turystyki Kulinarnej, Wyd; Dominik, P., Ed.; Vistula: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Szyszkowska, A. Jagiellońskie Smaki i Przysmaki; Vega Studia ADV, Tomasz Muller: Kwidzyń, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Skowronek, E.; Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Stasiak, A.; Tucki, A. The role of regional products in preserving traditional farming landscapes in the context of development of peripheral regions–Lubelskie Province, Eastern Poland. AUC Geogr. 2020, 55, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek-Kusiak, A. Zagospodarowanie niszy rynkowej w agroturystyce poprzez uwzględnienie w żywieniu posiłków wolnych od alergenów. Oeconomia Acta Sci. Pol. Ser. Oeconomia 2010, 9, 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Shank, D.B. Using crowdsourcing websites for sociological research: The case of Amazon Mechanical Turk. Am. Sociol. 2016, 47, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeni, R.F.; Stafford, F.; McGonagle, K.A.; Andreski, P. Response rates in national panel surveys. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2013, 645, 60–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carley-Baxter, L.R.; Hill, C.A.; Roe, D.J.; Twiddy, S.E.; Baxter, R.K.; Ruppenkamp, J. Does response rate matter? Journal editors’ use of survey quality measures in manuscript publication decisions. Surv. Pract. 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

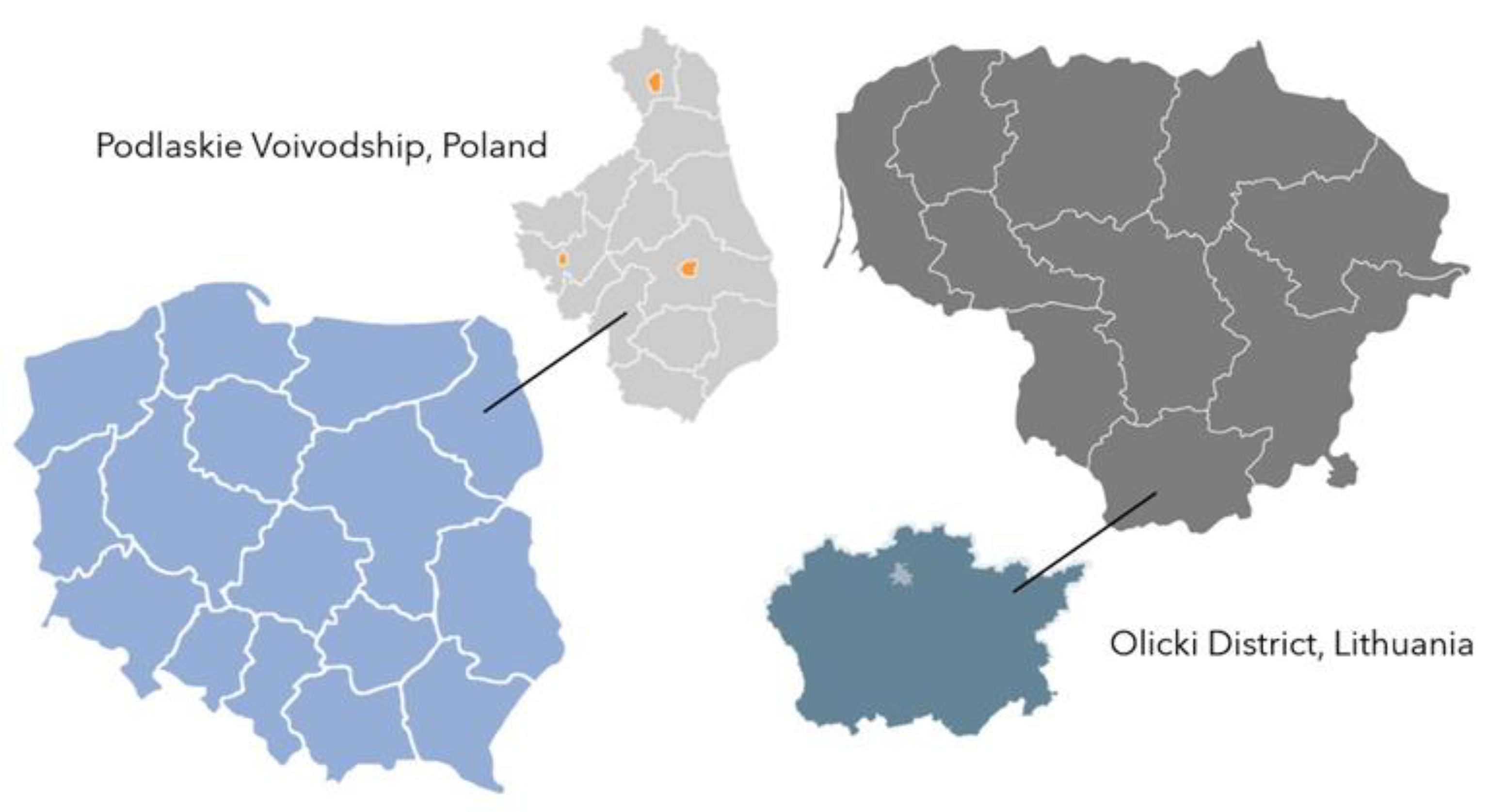

- POL Location Map. Available online: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plik:POL_location_map.svg (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Infopolska. Available online: http://www.infopolska.com.pl/polska/wojewodztwo_podlaskie_10 (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Panstwa. Available online: http://www.panstwa.com/mapa-litwa.html (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Lithuanian-Counties-Alytus. Available online: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okr%C4%99g_olicki#/media/Plik:Lithuanian-Counties-Alytus.svg (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Lang, M.; Stanton, J.; Qu, Y. Consumers’ evolving definition and expectations for local foods. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1808–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, M.; Sundbo, D.; Sundbo, J. Local food and tourism: An entrepreneurial network approach. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderighi, M.; Bianchi, C.; Lorenzini, E. The impact of local food specialities on the decision to (re) visit a tourist destination: Market-expanding or business-stealing? Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glica, J. Turystyka kulinarna Warmii i Mazur–próba opracowania szlaki kulinarnego na bazie listy produktów tradycyjnych. In Edukacyjna Rola Turystyki Kulinarnej Wyd; Dominik, P., Ed.; Vistula: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniczko, M.; Orłowski, D. Wydarzenia jako urozmaicona forma Turystyki kulinarnej na przykładzie Festiwalu “Europa na widelcu” we Wrocławiu. Zesz. Nauk. Ucz. Vistula 2017, 54, 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniecka-Skubina, E. Turystyka kulinarna jako forma turystyki kulturowej. In Kultura i Turystyka-Wokół Wspólnego Stołu; Krakowiak, B., Stasiak, A., Eds.; Regionalna Organizacja Turystyczna Województwa Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2015; pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Hall, C.M. Contemporary Tourism: An International Approach; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler, P.G.; Sucher, K.P.; Nelms, M.N. Food and Culture; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Okumus, B.; Cetinb, G. Marketing Istanbul as a culinary destination. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Okumus, F.; Okumus, B. Food tourism as a viable market segment: It’s all how you cook the numbers! J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Local food: A source for destination attraction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Crotts, J.C. Tourism and gastronomy: Gastronomy’s influence on how tourists experience a destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.A.; Izquierdo, C.; Laguna-Garcia, M. Culinary tourism experiences: The effect of iconic food on tourist intentions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitušíková, A. Cultural Heritagebased Urban Festival as a Tool to Promote Local Identity and City Marketing: The Case of the Radvaň Fair in Banská Bystrica, Slovakia. Croat. J. Ethnol. Folk. Res. 2020, 57, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoroiu, F.G.; Tudorache, P. Romanian Fairs and Festivals–Key Elements in Promoting the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Knowl. Horiz.-Econ. 2016, 8, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L. Food and Wine Festivals and Events around the World: Development, Management and Markets; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, S.; Medina-Viruel, M.J.; Di-Clemente, E.; Fruet-Cardozo, J.V. Motivations of the Culinary Tourist in the City of Trapani, Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, S.; Hall, D.; Williams, F. Policy, Support and Promotion for Food-Related Tourism Initiatives. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2003, 14, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruetharadhol, P.; Gebsombut, N. A bibliometric analysis of food tourism studies in Southeast Asia. Cogent. Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1733829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek-Kusiak, A.; Prukop, B.; Trafiałek, J. Motywy i bariery zakupu regionalnych produktów kulinarnych województwa lubelskiego. In Edukacyjna Rola Turystyki Kulinarnej Wyd; Dominik, P., Ed.; Vistula: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, R. Reinventing the gastronomic identity of Croatian tourist destinations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, A.; Jamshidi, D. Food tourism value: Investigating the factors that influence tourists to revisit. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, F.; Kock, G.; Scantlebury, M.M.G.; Okumus, B. Using Local Cuisines when Promoting Small Caribbean Island Destinations. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, E.; Perri, G. Food and Wine Tourism: Integrating Food, Travel and Territory; CABI Texts: Wallingford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Dish Type | Tourists in Poland | Tourists in Lithuania | t Test Value | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | |||||

| kartacze | 3.37 ± 1.33 | 383 | 3.47 ± 1.32 | 376 | 1.355 | 0.175 |

| kiszka ziemniaczana | 4.30 ± 1.26 | 383 | 4.98 ± 1.12 | 376 | 12.872 | 0.001 * |

| soczewiaki | 3.43 ± 1.43 | 383 | 3.02 ± 1.40 | 376 | 5.339 | 0.001 * |

| kołduny | 3.38 ± 1.29 | 383 | 3.39 ± 1.22 | 376 | 0.047 | 0.964 |

| czenaki | 3.76 ± 1.33 | 383 | 3.72 ± 1.24 | 376 | 0.646 | 0.517 |

| chłodnik litewski | 3.80 ± 1.33 | 383 | 3.81 ± 1.26 | 376 | 0.216 | 0.828 |

| Dish Type | Wilks’ Lambda: 0.539 F = 11.907 p < 0.001 * | Classification Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilks’ Lambda | F Value | p Value | Tourists in Poland | Tourists in Lithuania | |

| kiszka ziemniaczana | 0.537 | 299.23 | 0.001 * | 4.779 | 6.059 |

| kołduny | 0.561 | 1.803 | 0.178 | 1.553 | 1.605 |

| soczewiaki | 0.554 | 89.62 | 0.001 * | 0.146 | 0.310 |

| chłodnik litewski | 0.582 | 17.08 | 0.001 * | 0.271 | 0.035 |

| Constant | 14.336 | 18.164 | |||

| Dish Type and Consumption Place | Tourists in Poland | Tourists in Lithuania | t Test Value | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | |||||

| kartacze—restaurants | 3.20 ± 1.52 | 383 | 3.24 ± 1.42 | 376 | 0.457 | 0.647 |

| kartacze—fairs | 3.25 ± 1.45 | 383 | 3.20 ± 1.34 | 376 | 0.687 | 0.497 |

| kartacze—conferences | 2.77 ± 1.20 | 383 | 2.78 ± 1.18 | 376 | 0.183 | 0.850 |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—restaurants | 3..26 ± 1.35 | 183 | 3.18 ± 1.35 | 376 | 0.998 | 0.318 |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—fairs | 1.91 ± 1.34 | 383 | 1.77 ± 1.23 | 376 | 1.835 | 0.667 |

| kiszka—conferences | 2.65 ± 1.38 | 383 | 2.66 ± 1.33 | 376 | 0.206 | 0.836 |

| soczewiaki—restaurants | 3.56 ± 1.53 | 383 | 3.62 ± 1.44 | 376 | 0.756 | 0.449 |

| soczewiaki—fairs | 2.38 ± 1.49 | 383 | 2.61 ± 1.49 | 376 | 2.790 | 0.005 * |

| soczewiaki—conferences | 3.13 ± 1.51 | 383 | 3.29 ± 1.37 | 376 | 1.958 | 0.050 * |

| kołduny—restaurants | 2.19 ± 1.43 | 383 | 2.31 ± 1.44 | 376 | 1.450 | 0.147 |

| kołduny—fairs | 2.54 ± 1.46 | 383 | 2.74 ± 1.38 | 376 | 2.487 | 0.013 * |

| kołduny—conferences | 2.00 ± 1.35 | 383 | 2.21 ± 1.33 | 376 | 2.630 | 0.008 * |

| czenaki—restaurants | 2.57 ± 1.51 | 383 | 2.64 ± 1.39 | 376 | 0.894 | 0.372 |

| czenaki—fairs | 2.13 ± 1.36 | 383 | 2.33 ± 1.39 | 376 | 2.607 | 0.009 * |

| czenaki—conferences | 2.01 ± 1.31 | 383 | 1.99 ± 1.26 | 376 | 0.227 | 0.825 |

| chłodnik litewski—restaurants | 1.62 ± 1.13 | 383 | 1.68 ± 1.12 | 376 | 0.849 | 0.395 |

| chłodnik litewski—fairs | 1.48 ± 1.02 | 383 | 1.62 ± 1.18 | 376 | 3.265 | 0.001* |

| chłodnik litewski—conferences | 3.34 ± 1.29 | 383 | 3.47 ± 1.22 | 376 | 1.744 | 0.813 |

| Dish Type and Consumption Place | Wilks’ Lambda: 0.539 F = 11.927 p < 0.001 * | Classification Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilks’ Lambda | F Value | p Value | Tourists in Poland | Touristsin Lithuania | |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—fairs/festivals | 0.512 | 9.948 | 0.002 * | 3.767 | 3.586 |

| kartacze—fairs/festivals | 0.531 | 3.823 | 0.050 * | 2.477 | 2.879 |

| chłodnik litewski—conferences/business meetings | 0.522 | 3.205 | 0.074 | 2.103 | 2.190 |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—restaurants | 0.512 | 4.745 | 0.029 * | 1.343 | 1.242 |

| kołduny—fairs/festivals | 0.529 | 2.369 | 0.124 | 0.944 | 1.030 |

| soczewiaki—fairs/festivals | 0.548 | 1.650 | 0.199 | 0.846 | 0.899 |

| chłodnik litewski—fairs/festivals | 0.564 | 12.390 | 0.001 * | 0.641 | 0.424 |

| czenaki—conferences/business meetings | 0.517 | 1.480 | 0.228 | 0.438 | 0.377 |

| Constant | 22.185 | 22.455 | |||

| Dish Type | Tourists in Poland | Tourists in Lithuania | t Test Value | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | |||||

| kartacze—appearance | 3.39± 1.63 | 383 | 3.29 ± 1.53 | 376 | 1.172 | 0.241 |

| kartacze—flavour | 1.84 ± 1.26 | 383 | 2.09 ± 1.31 | 376 | 3.444 | 0.001 * |

| kartacze—smell | 1.95 ± 1.35 | 383 | 2.27 ± 1.40 | 376 | 4.078 | 0.001 * |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—appearance | 1.80 ± 1.23 | 383 | 1.81 ± 1.21 | 376 | 0.138 | 0.890 |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—flavour | 1.81 ± 1.29 | 383 | 1.96 ± 1.34 | 376 | 2.057 | 0.040 * |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—smell | 2.19 ± 1.43 | 383 | 2.30 ± 1.44 | 376 | 1.408 | 0.159 |

| soczewiaki—appearance | 1.96 ± 1.40 | 383 | 2.20 ± 1.39 | 376 | 3.102 | 0.002 * |

| soczewiaki—flavour | 2.47 ± 1.43 | 383 | 2.44 ± 1.51 | 376 | 1.089 | 0.376 |

| soczewiaki—smell | 1.82 ± 1.30 | 383 | 1.91 ± 1.28 | 376 | 1.042 | 0.297 |

| kołduny—appearance | 3.10 ± 1.52 | 383 | 3.15 ± 1.47 | 376 | 0.567 | 0.573 |

| kołduny—flavour | 2.54 ± 1.46 | 383 | 2.71 ± 1.39 | 376 | 2.046 | 0.040* |

| kołduny—smell | 3.97 ± 1.08 | 383 | 3.72 ± 1.19 | 376 | 3.948 | 0.001* |

| czenaki—appearance | 2.33 ± 1.25 | 383 | 2.51 ± 1.26 | 376 | 2.556 | 0.010* |

| czenaki—flavour | 2.99 ± 1.11 | 383 | 3.11 ± 1.13 | 376 | 1.849 | 0.064 |

| czenaki—smell | 2.80 ± 1.28 | 383 | 2.19 ± 1.31 | 376 | 0.865 | 0.386 |

| chłodnik litewski—appearance | 2.13 ± 1.28 | 383 | 2.19 ± 1.12 | 376 | 0.865 | 0.386 |

| chłodnik litewski—flavour | 2.93 ± 1.45 | 383 | 3.13 ± 1.42 | 376 | 2.507 | 0.012 * |

| chłodnik litewski—smell | 2.32 ± 1.40 | 383 | 2.46 ± 1.38 | 376 | 1.899 | 0.058 |

| Dish Type | Wilks’ lambda: 0.487 F = 19.912 p < 0.001 * | Classification Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilks’ Lambda | F Value | p Value | Tourists in Poland | Tourists in Lithuania | |

| kołduny—smell | 0.487 | 7.429 | 0.001 * | 5.028 | 5.876 |

| soczewiaki—flavour | 0.497 | 6.287 | 0.001 * | 5.423 | 5.012 |

| chłodnik litewski—flavour | 0.452 | 1.976 | 0.132 | 2.799 | 2.861 |

| kartacze—appearance | 0.489 | 3.221 | 0.027 * | 2.342 | 2.098 |

| chłodnik litewski—smell | 0.508 | 2.878 | 0.057 | 1.704 | 1.658 |

| kołduny—flavour | 0.467 | 2.978 | 0.048 * | 1.136 | 1.018 |

| kołduny—appearance | 0.518 | 1.238 | 0.287 | 0.741 | 0.688 |

| czenaki—flavour | 0.502 | 3.457 | 0.018 * | 0.089 | 0.163 |

| Constant | 19.717 | 19.817 | |||

| Dish Type | Tourists in Poland | Tourists in Lithuania | t Test Value | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | |||||

| kartacze—region’s promotion | 1.93± 1.35 | 383 | 2.07 ± 1.33 | 376 | 1.785 | 0.074 |

| kartacze—regional distinctiveness | 2.57 ± 1.46 | 383 | 2.62 ± 1.42 | 376 | 0.650 | 0.510 |

| kartacze—tourist attraction | 4.03 ± 1.09 | 383 | 3.76 ± 1.10 | 376 | 3.747 | 0.001 * |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—region’s promotion | 1.70 ± 1.25 | 383 | 1.73 ± 1.22 | 376 | 0.361 | 0.717 |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—regional distinctiveness | 2.71 ± 1.48 | 383 | 3.06 ± 1.44 | 376 | 4.143 | 0.001 * |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—tourist attraction | 2.48 ± 1.52 | 383 | 2.57 ± 1.46 | 376 | 0.744 | 0.373 |

| soczewiaki—region’s promotion | 1.53 ± 1.10 | 383 | 1.69 ± 1.11 | 376 | 2.424 | 0.015 * |

| soczewiaki—regional distinctiveness | 1.55 ± 1.13 | 383 | 1.60 ± 1.13 | 376 | 0.836 | 0.404 |

| soczewiaki—tourist attraction | 1.93 ± 1.32 | 383 | 2.02 ± 1.29 | 376 | 1.007 | 0.313 |

| kołduny—region’s promotion | 3.42 ± 1.66 | 383 | 3.27 ± 1.58 | 376 | 1.634 | 0.102 |

| kołduny—regional distinctiveness | 3.21 ± 1.42 | 383 | 3.30 ± 1.37 | 376 | 1.088 | 0.276 |

| kołduny—tourist attraction | 2.61 ± 1.50 | 383 | 2.90 ± 1.47 | 376 | 3.384 | 0.002 * |

| czenaki—region’s promotion | 2.85 ± 1.53 | 383 | 3.04 ± 1.49 | 376 | 2.249 | 0.024 * |

| czenaki—regional distinctiveness | 3.56 ± 1.53 | 383 | 3.62 ± 1.48 | 376 | 0.756 | 0.449 |

| czenaki—tourist attraction | 4.33 ± 0.97 | 383 | 4.16 ± 1.05 | 376 | 3.070 | 0.002 * |

| chłodnik litewski—region’s promotion | 1.704 ± 1.25 | 383 | 1.73 ± 1.19 | 376 | 0.367 | 0.717 |

| chłodnik litewski—regional distinctiveness | 2.71 ± 1.47 | 383 | 3.06 ± 1.44 | 376 | 4.143 | 0.001 * |

| chłodnik litewski—tourist attraction | 2.18 ± 1.52 | 383 | 2.57 ± 1.44 | 376 | 4.382 | 0.001 * |

| Dish Type | Wilks’ Lambda: 0.589 F = 13.968 p < 0.001 * | Classification Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilks’ Lambda | F Value | p Value | Tourists in Poland | Tourists in Lithuania | |

| czenaki—tourist attraction | 0.612 | 4.087 | 0.043 * | 3.953 | 3.831 |

| kartacze—tourist attraction | 0.593 | 6.567 | 0.010 * | 2.548 | 2.412 |

| kołduny—region’s promotion | 0.621 | 3.262 | 0.070 | 1.411 | 1.347 |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—regional distinctiveness | 0.616 | 3.634 | 0.050 * | 1.156 | 1.239 |

| kołduny—tourist attraction | 0.598 | 7.059 | 0.008 * | 0.631 | 0.714 |

| kiszka ziemniaczana—tourist attraction | 0.576 | 15.897 | 0.001 * | 0.525 | 0.688 |

| kołduny—regional distinctiveness | 0.602 | 3.542 | 0.086 | 0.383 | 0.412 |

| czenaki—regional distinctiveness | 0.618 | 4.090 | 0.041 * | 0.267 | 0.289 |

| Constant | 23.367 | 23.445 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soroka, A.; Mazurek-Kusiak, A.; Chmielewski, S.; Godlewska, A. Polish-Lithuanian Border Cuisine as an Idea for the Promotion and Expansion of the Region’s Tourist Attractiveness. Foods 2023, 12, 2606. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12132606

Soroka A, Mazurek-Kusiak A, Chmielewski S, Godlewska A. Polish-Lithuanian Border Cuisine as an Idea for the Promotion and Expansion of the Region’s Tourist Attractiveness. Foods. 2023; 12(13):2606. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12132606

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoroka, Andrzej, Anna Mazurek-Kusiak, Szymon Chmielewski, and Agnieszka Godlewska. 2023. "Polish-Lithuanian Border Cuisine as an Idea for the Promotion and Expansion of the Region’s Tourist Attractiveness" Foods 12, no. 13: 2606. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12132606

APA StyleSoroka, A., Mazurek-Kusiak, A., Chmielewski, S., & Godlewska, A. (2023). Polish-Lithuanian Border Cuisine as an Idea for the Promotion and Expansion of the Region’s Tourist Attractiveness. Foods, 12(13), 2606. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12132606