Exploring Consumer Preference towards the On-Farm Slaughtering of Beef in Germany: A Discrete Choice Experiment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Quality Attributes in Meat Purchase Decisions

1.1.1. Product Quality

1.1.2. Process Quality

1.1.3. Quality Control

1.1.4. User-Oriented Quality

1.2. Transport and Slaughter

- Pasture slaughter: Cattle are stunned and killed on the pasture. Subsequent transport and processing take place in a stationary part of a slaughterhouse.

- Semi-mobile slaughter: Cattle are stunned with a captive bolt gun and then killed and bled on the farm of origin. Subsequent transport and processing take place in a stationary part of an abattoir.

- Fully mobile slaughter: Cattle are stunned with a captive bolt gun on the farm of origin. Slaughter and bleeding are carried out on site. All further processing takes place in an EU-approved mobile slaughter unit [37].

Effects of Transport and Slaughter on Meat Quality

2. Materials and Methods

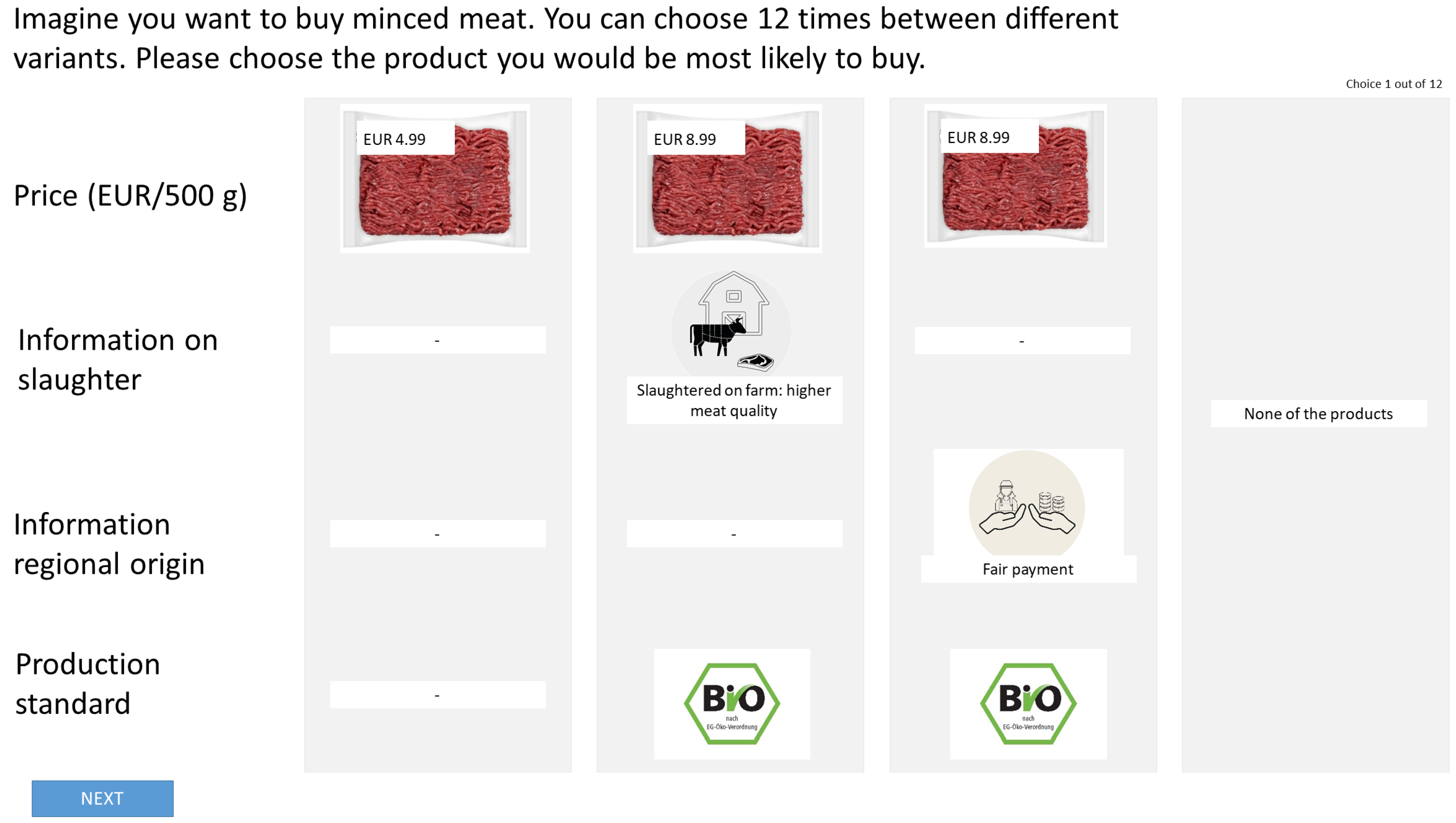

2.1. Discrete Choice Experiment

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Sampling

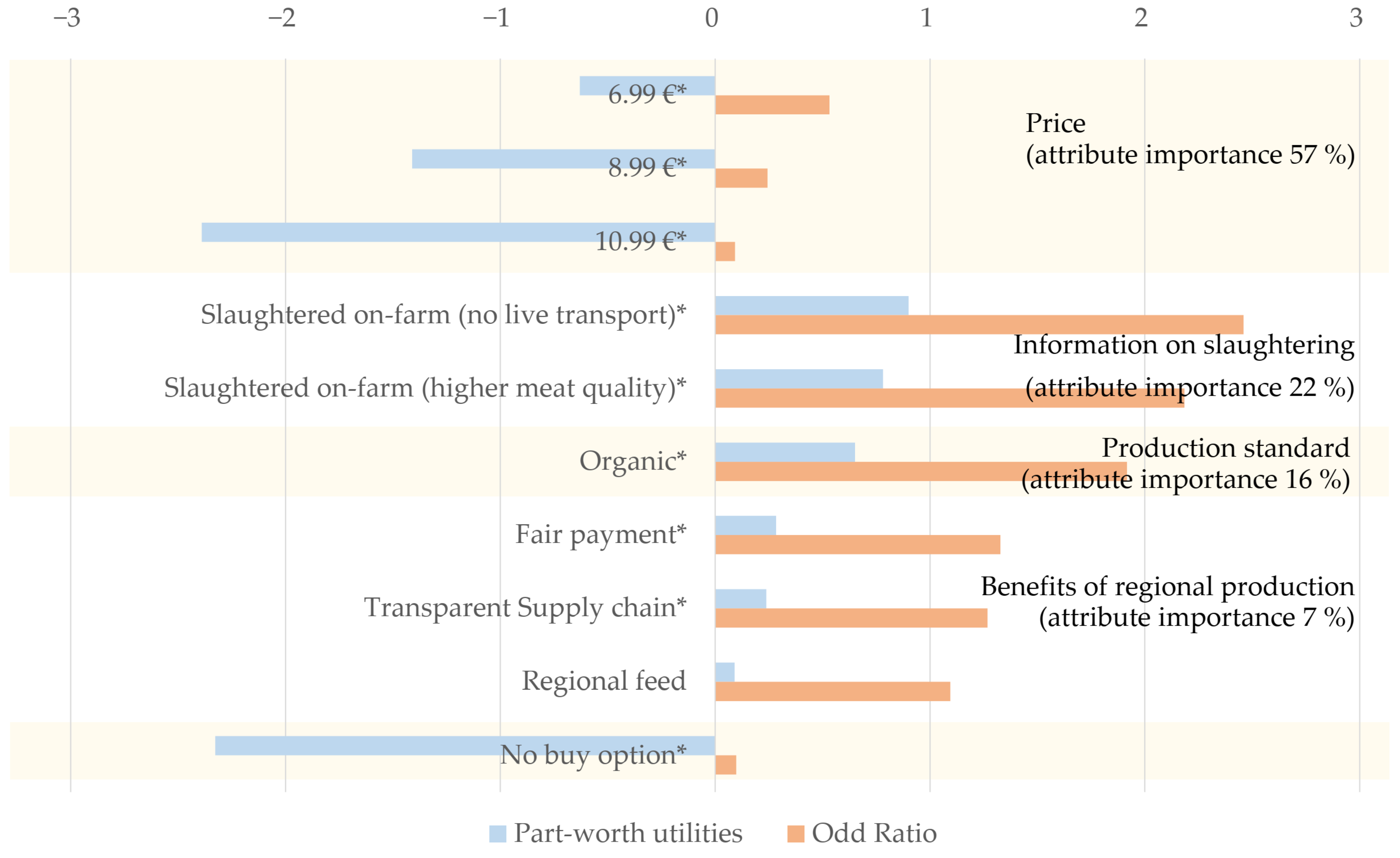

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Version | Task | Concept | Price | Information on Slaughter | Information Regional Production | Production Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 1 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 1 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 1 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

References

- Albersmeier, F.; Spiller, A. The Reputation of the German Meat Sector: A Structural Equation Model. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 59, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Attitudes of Europeans towards Animal Welfare. Report; Special Eurobarometer 442. 2016. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2875/884639 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- SPD; Bündnis 90/Die Grünen; FDP. Mehr Fortschritt Wagen: Koalitionsvertrag Zwischen Spd, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Und Fdp. 2021. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/974430/1990812/04221173eef9a6720059cc353d759a2b/2021-12-10-koav2021-data.pdf?download=1 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Klink-Lehmann, J.; Langen, N. Illuminating the ‘animal welfare’ consumer via different elicitation techniques. Meat Sci. 2019, 157, 107861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zander, K.; Hamm, U. Welche zusätzlichen ethischen Eigenschaften ökologischer Lebensmittel interessieren Verbraucher? Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 59, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, H.; Theuvsen, L. What do consumers think about farm animal welfare in modern agriculture? Attitudes and shopping behaviour. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damtew, A.; Erefa, Y.; Ebrahim, H.; Tsegaye, S.; Msgie, D. The Effect of long Distance Transportation Stress on Cattle: A Review. BJSTR 2018, 3, 3304–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.S.; Alvarez, J.; Bicout, D.J.; Calistri, P.; Depner, K.; Drewe, J.A.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Gonzales Rojas, J.L.; Schmidt, C.G.; Michel, V.; et al. Welfare of cattle at slaughter. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarnido-López, P.; Resconi, V.C.; Campo, M.d.M.; Guerrero, A.; María, G.A.; Olleta, J.L. Slaughtering of heifers in a local or an industrial abattoir: Animal welfare and meat quality consequences. Livest. Sci. 2022, 259, 104904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarten, H. Es War Einmal—Struktur der Schlachthöfe in Ostdeutschland. Bauernzeitung [Online]. 24 September 2020. Available online: https://www.bauernzeitung.de/hintergrund/es-war-einmal-struktur-der-schlachthoefe-in-ostdeutschland/ (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Wagner, B.; Hassel, A. Posting, subcontracting and low-wage employment in the German meat industry. Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2016, 22, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bio Rind & Fleisch EZG GmbH. Teilmobile Schlachtung. 2023. Available online: https://biorind.de/willkommen/teilmobile-schlachtung/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Alnatura. Alnatura ist Erster Bio-Einzelhändler Mit Fleisch aus Weideschlachtung. Darmstadt. 2021. Available online: https://www.alnatura.de/de-de/ueber-uns/presse/pressemitteilungen/weideschlachtung/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Carlsson, F.; Frykblom, P.; Lagerkvist, C.J. Consumer willingness to pay for farm animal welfare: Mobile abattoirs versus transportation to slaughter. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2007, 34, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.F.; Botreau, R.; Legrand, I.; Polkinghorne, R.; Pethick, D.W.; Lherm, M.; Picard, B.; Doreau, M.; Terlouw, E.M.C. Win–win strategies for high beef quality, consumer satisfaction, and farm efficiency, low environmental impacts and improved animal welfare. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2014, 54, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernqvist, F.; Ekelund, L. Credence and the effect on consumer liking of food—A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 32, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klink, J.; Langen, N. Are animal welfare aspects of relevance in consumers’ purchase decision? Proc. Syst. Dyn. Innov. Food Netw. 2015, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.C.; Umberger, W.J. “Pick the Tick”: The Impact of Health Endorsements on Consumers’ Food Choices, 1st ed. Joint EAAE/AAEA Seminar “The Economics of Food, Food Choice and Health”. 2010. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ags/eaa115/116436.html (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Van Wezemael, L.; Verbeke, W.; de Barcellos, M.D.; Scholderer, J.; Perez-Cueto, F. Consumer perceptions of beef healthiness: Results from a qualitative study in four European countries. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsø, K.; Bredahl, L.; Grunert, K.G.; Scholderer, J. Consumer perception of the quality of beef resulting from various fattening regimes. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 94, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risius, A.; Hamm, U. Exploring Influences of Different Communication Approaches on Consumer Target Groups for Ethically Produced Beef. J. Agric. Env. Ethics 2018, 31, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W.; van Poucke, E.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Do citizens and farmers interpret the concept of farm animal welfare differently? Livest. Sci. 2008, 116, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, S.C.; Busch, G.; Spiller, A. Tiertransporte in der Schweinehaltung: Führen mehr Informationen und Wissen bei Verbrauchern zu einer positiveren Einstellung? GJAE 2017, 66, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.J.; Santini, F. The sustainability of “local” food: A review for policy-makers. Rev. Agric. Food Env. Stud. 2021, 103, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J.; de Silva Kanakaratne, M. The mindful consumer: Balancing egoistic and altruistic motivations to purchase local food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, C.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions and preferences for local food: A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, J.; Haack, M.; Häring, A.M. Co-production of Business Models for Pasture-Based Beef in North-East Germany—Integrating Consumers Preferences. Proc. Food Syst. Dyn. Innov. 2022, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, M. Geht Geiz über Tierschutz? Available online: https://de.statista.com/infografik/17110/marktanteile-ausgewaehlter-fleischprodukte (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Stolz, H.; Blattert, S.; Rebholz, T.; Stolze, M. Biobarometer Schweiz: Wovon die Kaufentscheidung für Biolebensmittel abhängt. Agrar. Schweiz 2017, 8, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Enneking, U. Kaufbereitschaft bei Verpackten Schweinefleischprodukten im Lebensmitteleinzelhandel: Realexperiment und Kassenzonen-Befragung. 2018. Available online: https://www.hs-osnabrueck.de/fileadmin/HSOS/Homepages/Personalhomepages/Personalhomepages-AuL/Enneking/Tierwohlstudie-HS-Osnabrueck_Teil-Realdaten_17-Jan-2019.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Risius, A.; Hamm, U. The effect of information on beef husbandry systems on consumers’ preferences and willingness to pay. Meat Sci. 2017, 124, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremmer, P.; Hempel, C.; Hamm, U.; Busch, C. Zielkonflikt beim Lebensmitteleinkauf: Konventionell Regional, Ökologisch Regional oder Ökologisch aus Entfernteren Regionen? 2016. Available online: https://www.orgprints.org/30487/ (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Statista. Fleischverarbeitung in Deutschland. Available online: https://de.statista.com/themen/4069/fleischverarbeitung-in-deutschland/#topicHeader__wrapper (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Hultgren, J. Is livestock transport a necessary practice? Mobile slaughter and on-farm stunning and killing before transport to slaughter. CABI Rev. 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, A.; Raj, M.; Grandin, T. Animal Welfare at Slaughter; 5m Books Ltd.: Essex, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781912178056. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulations Commission Delegated Regulation (Eu) 2021/1374 of 12 April 2021 amending Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Specific Hygiene Requirements for Food of Animal Origin. No. 6. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32021R1374 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Land Brandenburg. Leitfaden Zur Schlachtung Im Herkunftsbetrieb: Umsetzungshinweise für die Durchführung und Überwachung der Schlachtung von Rindern, Schweinen und Einhufern im Herkunftsbetrieb. 2022. Available online: https://msgiv.brandenburg.de/sixcms/media.php/9/Leitfaden_Schlachtung_Herkunftsbetrieb_20220720.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Pérez-Linares, C.; Barreras, S.A.; Sánchez, L.E.; Herrera, S.B.; Figueroa-Saavedra, F. The effect of changing the pre-slaughter handling on bovine cattle DFD meat. Rev. MVZ Córdoba 2015, 20, 4688–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.S.; Rødbotten, R.; Grøndahl, A.M.; Friestad, M.; Andersen, I.L.; Mejdell, C.M. Mobile abattoir versus conventional slaughterhouse—Impact on stress parameters and meat quality characteristics in Norwegian lambs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 149, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultgren, J.; Arvidsson Segerkvist, K.; Berg, C.; Karlsson, A.H.; Algers, B. Animal handling and stress-related behaviour at mobile slaughter of cattle. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 177, 104959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Weiber, R. Fortgeschrittene Multivariate Analysemethoden; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Louviere, J.J.; Pihlens, D.; Carson, R. Design of Discrete Choice Experiments: A Discussion of Issues That Matter in Future Applied Research. J. Choice Model. 2011, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Rose, J.M.; Rose, J.M.; Greene, W.H. Applied Choice Analysis: A Primer; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; ISBN 9780521844260. [Google Scholar]

- Lizin, S.; Rousseau, S.; Kessels, R.; Meulders, M.; Pepermans, G.; Speelman, S.; Vandebroek, M.; van den Broeck, G.; van Loo, E.J.; Verbeke, W. The state of the art of discrete choice experiments in food research. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K. A New Approach to Consumer Theory. J. Political Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. The measurement of urban travel demand. J. Public Econ. 1974, 3, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, M.; Spiller, A.; Risius, A. Do consumers prefer pasture-raised dual-purpose cattle when considering meat products? A hypothetical discrete choice experiment for the case of minced beef. Meat Sci. 2021, 177, 108494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumrow, S.; Hudson, D.; Sarasty, O.; Carpio, C.; Bratcher, C. Consumer preferences for worker and supply chain risk mitigation in the beef supply chain in response to COVID-19 pandemic. Agribusiness 2023, 112, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennecke, B.E.; Townsend, A.M.; Hayes, D.J.; Lonergan, S.M. A study of the factors that influence consumer attitudes toward beef products using the conjoint market analysis tool. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 2639–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proplanta. Die Beliebtesten Fleischprodukte in Deutschland. 2008. Available online: https://www.proplanta.de/agrar-nachrichten/verbraucher/die-beliebtesten-fleischprodukte-in-deutschland_article1218013603.html (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Profeta, A.; Hamm, U. Do consumers care about local feedstuffs in local food? Results from a German consumer study. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 88, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chang, M.; Park, J. Survival analysis for Hispanic ELL students’ access to postsecondary schools: Discrete model or Cox regression? Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2018, 41, 514–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.H. Consumer preferences for food labels on tomatoes in Germany—A comparison of a quasi-experiment and two stated preference approaches. Appetite 2016, 103, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.H.; Merz, N. Consumer preferences for organic labels in Germany using the example of apples—Combining choice-based conjoint analysis and eye-tracking measurements. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.M. A Guide to Measuring and Interpreting Attribute Importance. Patient—Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2019, 12, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 9781139480376. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Statistiken zur Einwohnerzahl in Deutschland. Available online: https://de.statista.com/themen/20/einwohnerzahl/#dossierKeyfigures (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Meade, A.W.; Craig, S.B. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSimone, J.A.; Harms, P.D.; DeSimone, A.J. Best practice recommendations for data screening. J. Organiz. Behav. 2015, 36, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo del Bosque, C.I.; Busch, G.; Spiller, A.; Risius, A. My Meat Does Not Have Feathers: Consumers’ Associations with Pictures of Different Chicken Breeds. J. Agric. Env. Ethics 2020, 33, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, J.R.; Hohle, S.M. Meat eaters by dissociation: How we present, prepare and talk about meat increases willingness to eat meat by reducing empathy and disgust. Appetite 2016, 105, 758–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradidge, S.; Zawisza, M.; Harvey, A.J.; McDermott, D.T. A structured literature review of the meat paradox. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.W.; Cohen, A.R. Explorations in Cognitive Dissonance; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Thorslund, C.A.H.; Sandøe, P.; Aaslyng, M.D.; Lassen, J. A good taste in the meat, a good taste in the mouth—Animal welfare as an aspect of pork quality in three European countries. Livest. Sci. 2016, 193, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühl, S.; Bayer, E.; Busch, G. Should organic animals be slaughtered differently from non-organic animals? A cluster analysis of German consumers. Org. Agr. 2022, 12, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampa, E.; Schipmann-Schwarze, C.; Hamm, U. Consumer perceptions, preferences, and behavior regarding pasture-raised livestock products: A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 82, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Hartmann, M.; Langen, N. The Role of Trust in Explaining Food Choice: Combining Choice Experiment and Attribute Best-Worst Scaling. Foods 2020, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Schroeder, T.C. Are Choice Experiments Incentive Compatible? A Test with Quality Differentiated Beef Steaks. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 86, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament; European Council. Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32018R0848&from=EN (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Kohte, W.; Rabe-Rosendahl, C. Zerlegung des Arbeitsschutzes in der Fleischindustrie durch Werkverträge—und die Notwendigkeit integrativen Arbeitsschutzes. Z. Arbeitswiss. 2020, 74, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münchhausen, S.v.; Fink-Keßler, A.; Häring, A. “Beim Fleisch Läuft’s Immer Etwas Anders!” Perspektiven zum Aufbau Wertebasierter Wertschöpfungsketten; Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG.: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wägli, S.; Hamm, U. Verbraucherpräferenzen Bezüglich der Futtermittelherkunft im Öko-Landbau; Verlag Dr. Köster: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, S.A.; Gregg, D.; Singh, M. Understanding the role of social desirability bias and environmental attitudes and behaviour on South Australians’ stated purchase of organic foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 74, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumpal, I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2025–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkova, S.; Grunert, K.G.; Juhl, H.J.; Wasowicz-Kirylo, G.; Stysko-Kunkowska, M.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Attention mediates the effect of nutrition label information on consumers’ choice. Evidence from a choice experiment involving eye-tracking. Appetite 2014, 76, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Attribute | Quality | Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Price (EUR/500 g) | User-oriented quality | 4.99 | 6.99 | 9.99 | 10.99 |

| Information on slaughter | Process quality, product quality | No information | Slaughtered on farm, no live transport | Slaughtered on farm, higher meat quality | -- |

| Production standard | Quality control | No information | Organic production | -- | -- |

| Information on benefits of regional origin | Process quality | No information | Fair payment | Transparent supply chain | Regional feed |

| Key Demographic | Distribution in % |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male: 50.3; Female: 49.3; Diverse: 0.3 |

| Age in years | 18–24: 10.1 25–34: 14.6 35–44: 15.2 45–54: 18.7 55–64: 17.2 35–64: 51 65 and over: 24 |

| Education | No vocational qualification: 3.51 Currently in school or vocational training: 10.78 Completed vocational education: 51.63 Academic degree: 33.08 |

| Monthly net household income in EUR | Under 1000: 7.8 1000–2000: 25.5 2000–3000: 24 3000–4000: 16.4 4000–5000: 10.6 Over 5000: 13.4 1500–3500: 46.25 Over 3500: 31.2 |

| Size of municipality | Under 5000: 16.29 5000–10,000: 18.05 10,000–100,000: 22.81 100,000–500,000: 15.79 Over 500,000: 21.8 |

| Attribute | Attribute Levels | WTP for Attribute Levels | Average WTP for Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information on slaughter | Slaughtered on-farm (no live transport) Slaughtered on-farm (higher meat quality) | EUR 2.26 EUR 1.96 | EUR 2.11 |

| Production standard | Organic | EUR 1.63 | EUR 1.63 |

| Information on benefits of regional origin | Fair payment Transparent supply chain Regional feed | EUR 0.71 EUR 0.60 EUR 0.23 | EUR 0.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lauterbach, J.; Bruns, A.J.; Häring, A.M. Exploring Consumer Preference towards the On-Farm Slaughtering of Beef in Germany: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Foods 2023, 12, 3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12183473

Lauterbach J, Bruns AJ, Häring AM. Exploring Consumer Preference towards the On-Farm Slaughtering of Beef in Germany: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Foods. 2023; 12(18):3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12183473

Chicago/Turabian StyleLauterbach, Josephine, Antonia Johanna Bruns, and Anna Maria Häring. 2023. "Exploring Consumer Preference towards the On-Farm Slaughtering of Beef in Germany: A Discrete Choice Experiment" Foods 12, no. 18: 3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12183473

APA StyleLauterbach, J., Bruns, A. J., & Häring, A. M. (2023). Exploring Consumer Preference towards the On-Farm Slaughtering of Beef in Germany: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Foods, 12(18), 3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12183473