Australian Sheep Producers’ Knowledge of and Attitude towards Post-Harvest Feedback: A Mixed-Methods Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What feedback do Australian sheep producers receive regarding carcase and offal from the abattoirs?

- Is there any relationship to the feedback received and the enterprise type/management/sale method?

- Are Australian sheep producers satisfied with the feedback they receive?

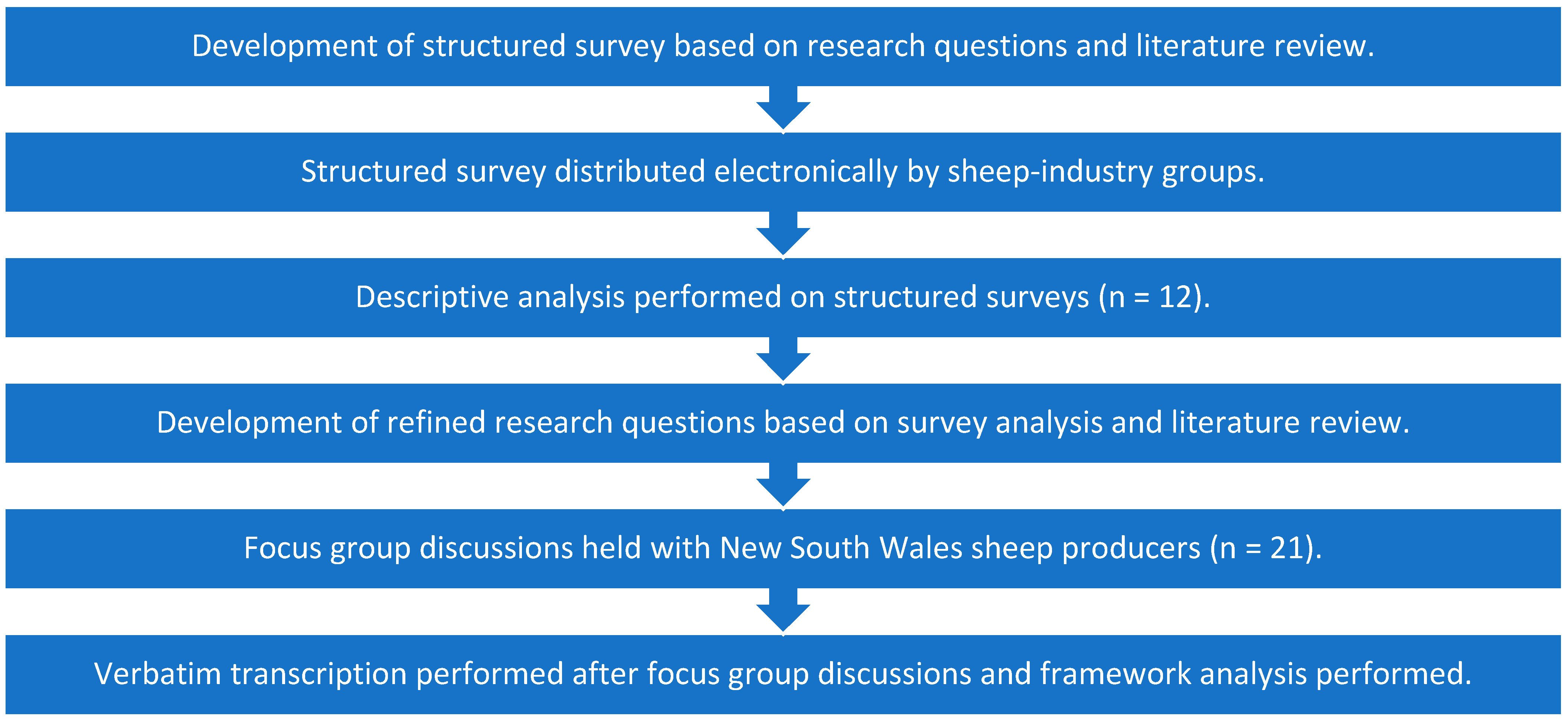

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structured Survey

2.1.1. Study Design and Setting

2.1.2. Sampling and Recruitment

2.1.3. Data Collection

- Section 1: Demographics—age, gender, and farming experience;

- Section 2: Enterprise information—structure, management, products, sale methods, and end points of products;

- Section 3: Post-farm-gate: feedback received from processors—feedback frequency, content, and value;

- Section 4: Household meat and offal consumption and understanding of the comparative nutrient value of these products.

2.1.4. Data Analysis

2.2. Focus Group Discussions

2.2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2.2. Sampling and Recruitment

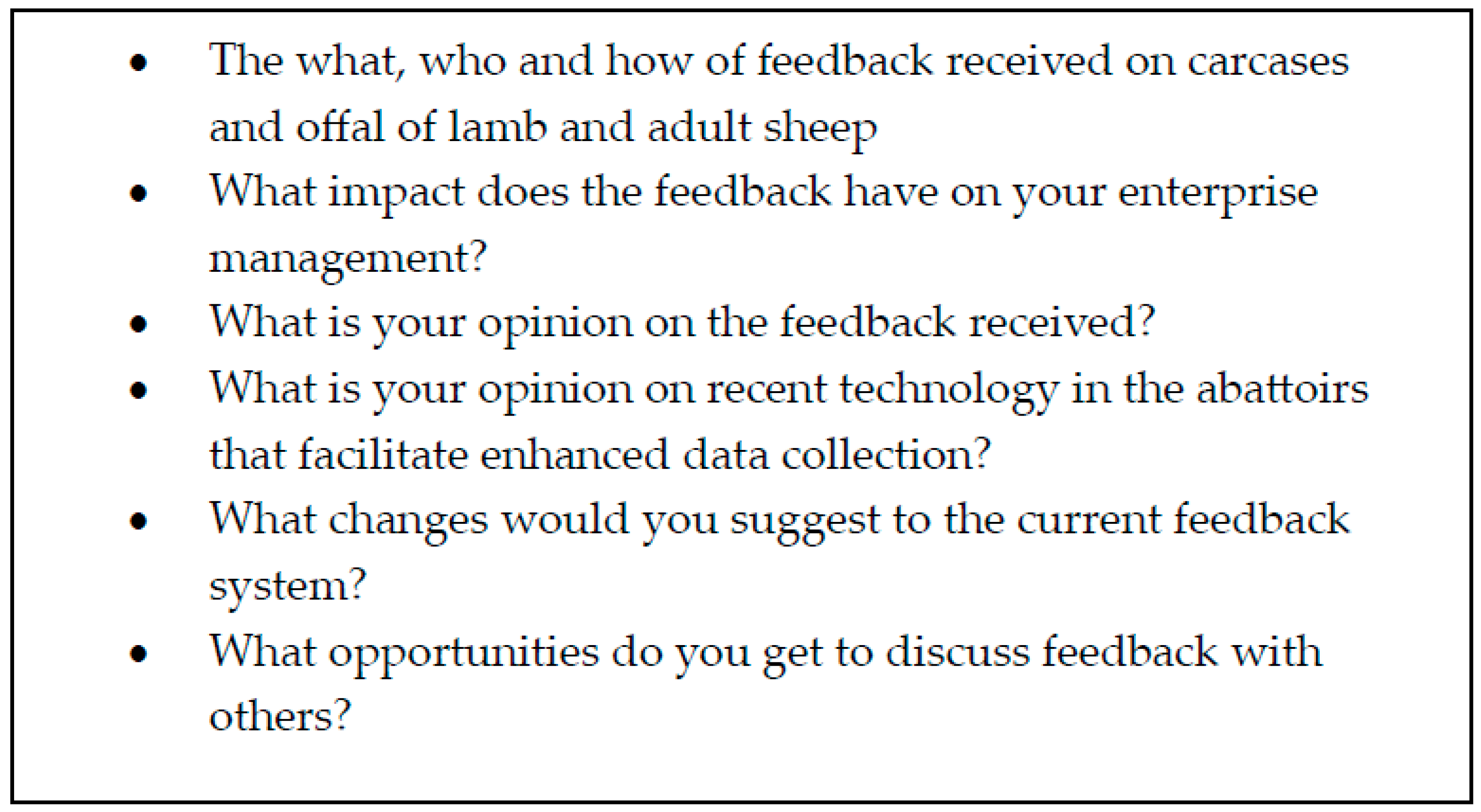

2.2.3. Data Collection

2.2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Structured Survey

3.1.1. Demographics

3.1.2. Enterprise Information

3.1.3. Post-Farm-Gate

3.2. Focus Group Discussions

- Situation, knowledge, and attitudes of producers to the feedback system;

- Factors, enablers, and barriers in the feedback system;

- Equity in the feedback system;

- Sustainability of the value chain.

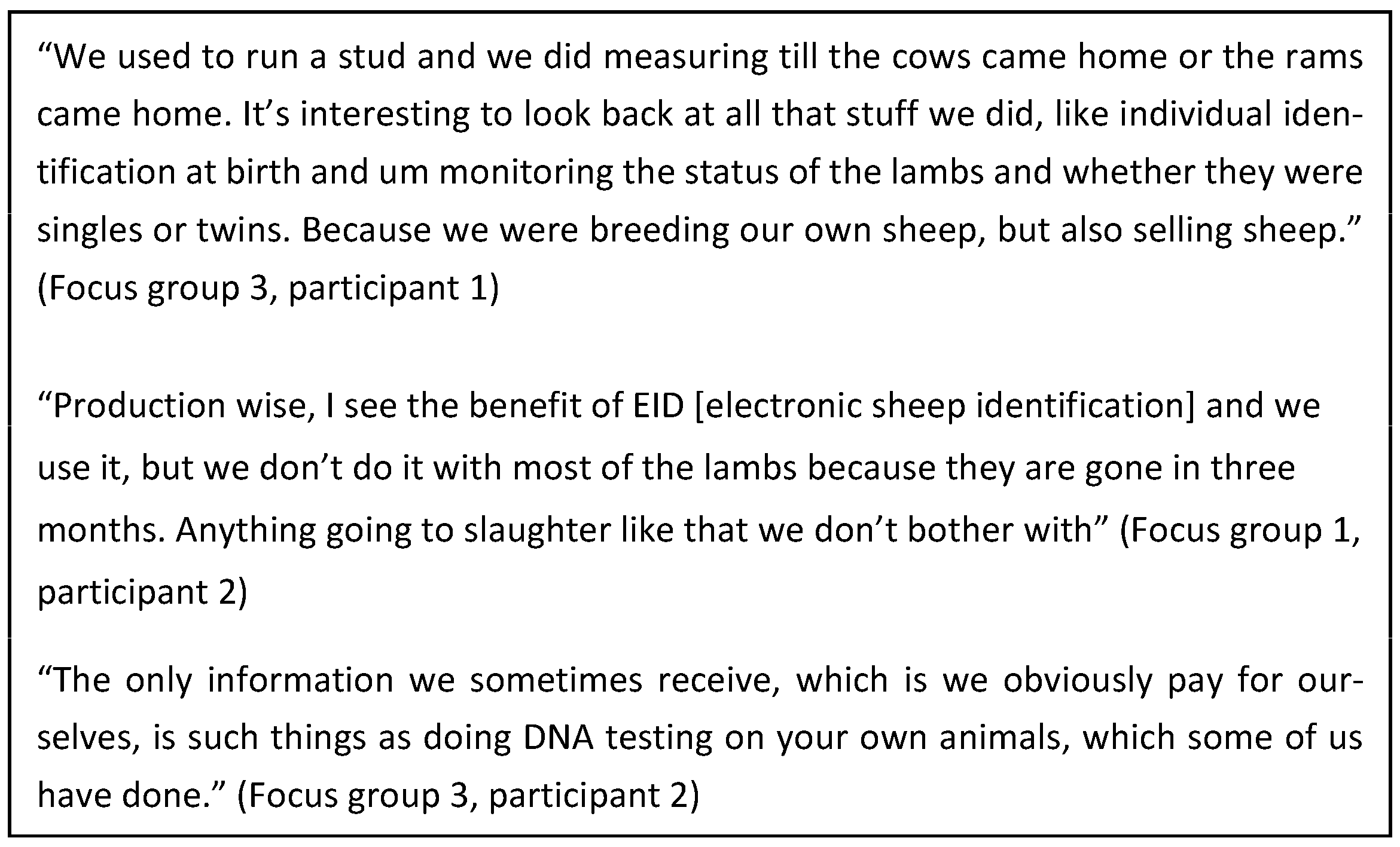

3.2.1. Situation, Knowledge, and Attitudes of Producers to the Feedback System

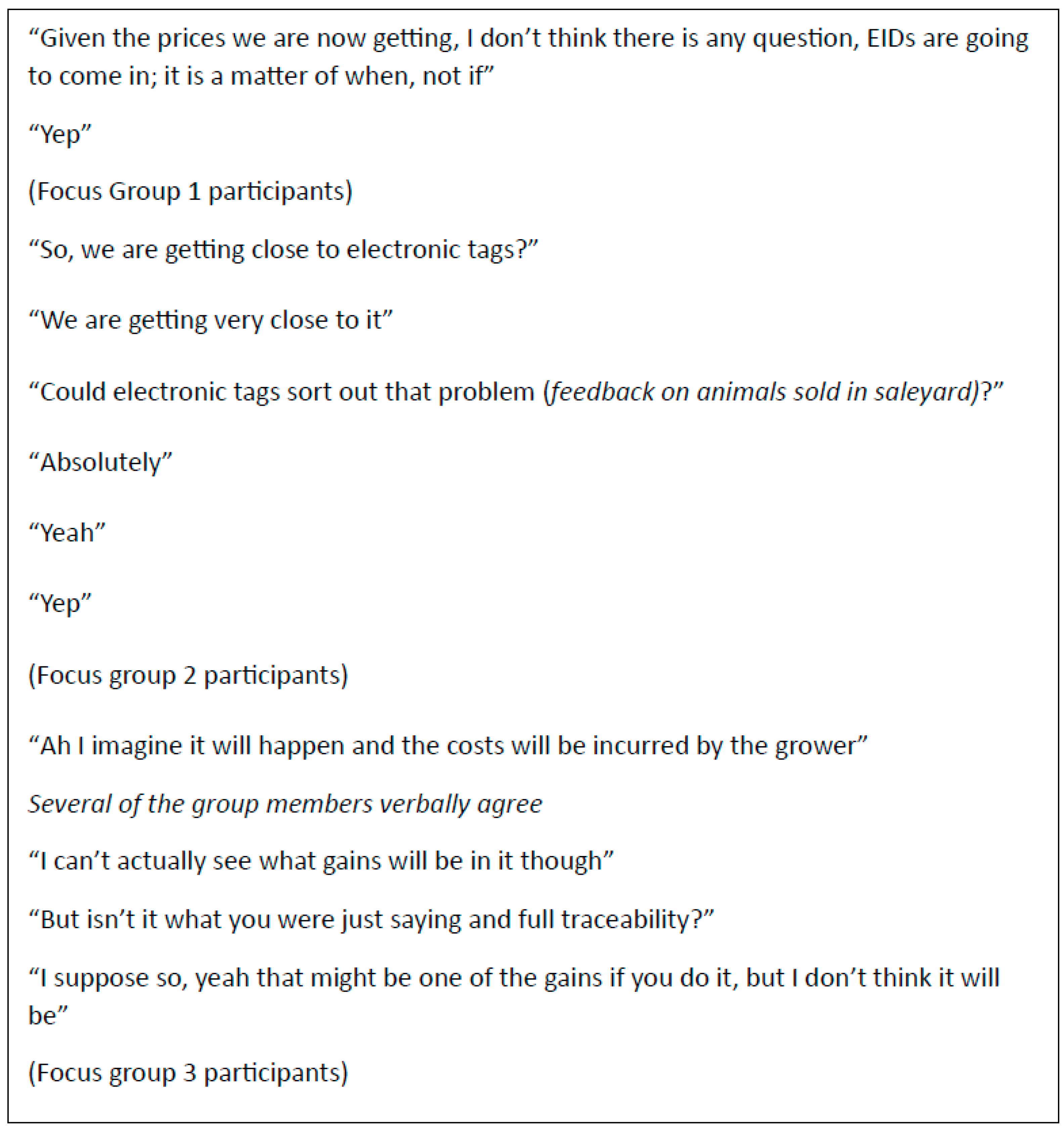

3.2.2. Barriers and Enablers in the Feedback System

3.2.3. Equity in the Feedback System for Stakeholders

3.2.4. Sustainability of the Value Chain

4. Discussion

- Routinely including the reason for full carcase condemnations on the kill sheet;

- Publishing the number of full carcase condemnations in the national agricultural dataset, as the New Zealand Government does [33];

- Expanding the current national data analysis and reporting from the National Sheep Health Monitoring Project to increase the frequency (consider quarterly instead of annually) and geographic granularity (consider natural resource management regions as base geographic region instead of jurisdiction).

- Providing feedback to producers regardless of sale method or abattoir. The feasibility of this will increase when individual sheep electronic identification is mandated nationally in 2025 [31]. Consideration must be given to the disproportionate costs to small-to-medium-size abattoirs of setting up and maintaining data collection and dissemination systems [6].

- Routinely providing quantified feedback on not only carcase condemnations but also offal condemnations. Some of these animal health conditions have little to no effect on sheep productivity, e.g., sheep measles and hydatids, and the only way a producer may know if the condition is present is through post-mortem examination of the animals. The control of hydatids is of public health significance [34].

- Providing feedback to producers if the animals slaughtered from their farm were free from any defects and hence did not require any condemnation of offal or carcase/carcase meat. This is consistent with the findings from the review of the South Australian Enhanced Abattoir Surveillance Program [32].

- Expand the network of unbiased advisors that are currently available and accessible to sheep producers to discuss feedback and facilitate evidence-based management decisions at the enterprise level. These same advisors could assist with developing and implementing regional and jurisdictional animal health programs, including the monitoring, evaluation and review of feedback system.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- HLPE. Food Losses and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper, M.; Cui, H.D. Using Food Loss Reduction to Reach Food Security and Environmental Objectives–A Search for Promising Leverage Points. Food Policy 2021, 98, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcadis, National Food Waste Baseline: Final Assessment Report. 2019; p. 102. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.au/protection/waste/food-waste (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Food Regulation Standing Committee. Australian Standard for the Hygienic Production and Transportation of Meat and Meat Products for Human Consumption; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2007; p. 81. Available online: http://www.publish.csiro.au (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Spooncer, B. Australian Beef and Sheep Meat Edible Offal Market Review 2012; Kurrajong Meat Technology Pty Ltd.: North Sydney, Australia, 2014; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- GHD Hassell. Cost Benefits of e-Surveillance System for Animal Health Monitoring; Meat and Livestock Australia: North Sydney, Australia, 2011; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Animal Health Australia. National Sheep Health Monitoring Project. 2021. Available online: https://www.animalhealthaustralia.com.au/nshmp/ (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- FAOSTAT. Crops and Livestock Products; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Value of Agricultural Commodities Produced, Australia; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Agricultural Commodities, Australia; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Macquarie Dictionary. Macquarie Dictionary Online; Macquarie Dictionary: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, S.Z.Y.; Brown, D.J.; Banks, R.G. Data capture through Australian beef cattle and meat sheep value chains: Opportunities for enhanced feedback to commercial producers. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 58, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council; Australian Research Council, and Universities Australia. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (updated 2018); Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2018; p. 110.

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Best Practices for Survey Research; American Association for Public Opinion Research: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2008; p. 9. Available online: https://www-archive.aapor.org/Standards-Ethics/Best-Practices.aspx (accessed on 8 May 2017).

- de Vaus, D.A. Collecting Survey Data. In Surveys in Social Research; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2002; p. 379. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, I.M. Questionnaire Design. In Marketing Research and Information Systems; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1997; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, R. Sampling methods for web and email surveys. In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods; Fielding, N., Lee, R., Blank, G., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2008; pp. 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzinger, J. Introducing focus groups. Br. Med. J. 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barwell, R. National Sheep Health Monitoring Project; Meat and Livestock Australia: North Sydney, Australia, 2019; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- AUSMEAT. Handbook of Australian Sheepmeat Processing-the AUSMEAT Language; AUSMEAT: Murarrie, Australia, 2020; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Agricultural Commodities, Australia and State/Territory and NRM Regions-2017–18; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Local Land Services. Local Land Services. 2023. Available online: https://www.lls.nsw.gov.au/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Rabiee, F. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderifar, M.; Goli, H.; Ghaljaie, F. Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 2017, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Analyzing Qualitative Data; Bryman, A., Burgess, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meat and Livestock Australia. Glossary 2023. Available online: https://www.mla.com.au/general/glossary/#glossarySection_O (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Department of Primary Industries and Regions. Enhanced Abattoir Surveillance Program. 2023. Available online: https://pir.sa.gov.au/biosecurity/animal_health/animal_species/sheep/health/enhanced_abattoir_surveillance_program (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Farm Biosecurity. Mandatory Electronic Identification for Australian Sheep and Goats: What You Need to Know. 2023. Available online: https://www.farmbiosecurity.com.au/mandatory-electronic-identification-for-australian-sheep-and-goats-what-you-need-to-know/ (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Dickason, C. Animal Health Feedback to Producers; Primary Industries and Regions South Australia, Ed.; Mintrac: Helensburgh, Australia, 2016; p. 26. Available online: https://www.mintrac.com.au/docs/pdf/20161118_Celia_Dickason.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Stats NZ Infoshare, Livestock Slaughtering-LSS; New Zealand Government: Wellington, DC, USA, 2022.

- World Health Organization. Echinococcosis 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/echinococcosis (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Xue, L.; Liu, G.; Parfitt, J.; Liu, X.; Van Herpen, E.; Stenmarck, Å.; O’Connor, C.; Östergren, K.; Cheng, S. Missing Food, Missing Data? A Critical Review of Global Food Losses and Food Waste Data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6618–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category Name | Description | Codes | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Producer insights | Content of feedback received and process of how this is received both historically and in the present; actions members have taken based on the feedback and opportunities to discuss feedback | Feedback historical Feedback content current Feedback process current Feedback actions taken Opportunities to discuss feedback | Situation, knowledge, and attitudes of producers to the feedback system |

| Variation | Factors identified that create variation in the feedback received by New South Wales sheep producers | Enterprise type Abattoir/agent Sale method Jurisdiction | |

| Knowledge—industry | Producers’ knowledge of industry processes and practices and how this relates to feedback | Meat processing Industry systems Engaged producers Trusted sources of knowledge Knowledge is power | |

| Relationships | Stakeholder relationships and how they influence/impact the feedback system | Relationship with agent Relationship with abattoirs Relationship with government Role of other value chain actors Perceived power of producers | Barriers and enablers in the feedback system |

| Progress | Opinion of feedback and how it has changed over time, and opportunities into the future to make changes to the feedback system | Abattoir technology Opinion on feedback Future feedback suggestions Future actions from feedback | |

| Markets | The influence of markets on value of products and in turn the cost: benefit of a feedback system to different actors in the value chain | Branding and marketing Export carcase markets Potential offal markets | Equity in the feedback system |

| Value chain | Value chain factors that directly affect the feedback process in the Australian sheep meat value chain | Data governance Product ownership and value Sale and sale method Traceability Who pays for the feedback system? | |

| Planetary Health | The influence of positive human health, environment health and animal welfare outcomes on the drive for feedback in the Australian sheep meat value chain | Environment Human health Social license to farm | Sustainability of the value chain |

| Knowledge—food | How food technology, choices, and acceptance influence demand for products | Food acceptance Food choice Food knowledge Food technology |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wingett, K.; Alders, R. Australian Sheep Producers’ Knowledge of and Attitude towards Post-Harvest Feedback: A Mixed-Methods Case Study. Foods 2023, 12, 4264. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234264

Wingett K, Alders R. Australian Sheep Producers’ Knowledge of and Attitude towards Post-Harvest Feedback: A Mixed-Methods Case Study. Foods. 2023; 12(23):4264. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234264

Chicago/Turabian StyleWingett, Kate, and Robyn Alders. 2023. "Australian Sheep Producers’ Knowledge of and Attitude towards Post-Harvest Feedback: A Mixed-Methods Case Study" Foods 12, no. 23: 4264. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234264

APA StyleWingett, K., & Alders, R. (2023). Australian Sheep Producers’ Knowledge of and Attitude towards Post-Harvest Feedback: A Mixed-Methods Case Study. Foods, 12(23), 4264. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234264