Protein Hydrolysates from Fishery Processing By-Products: Production, Characteristics, Food Applications, and Challenges

Abstract

:1. Introduction

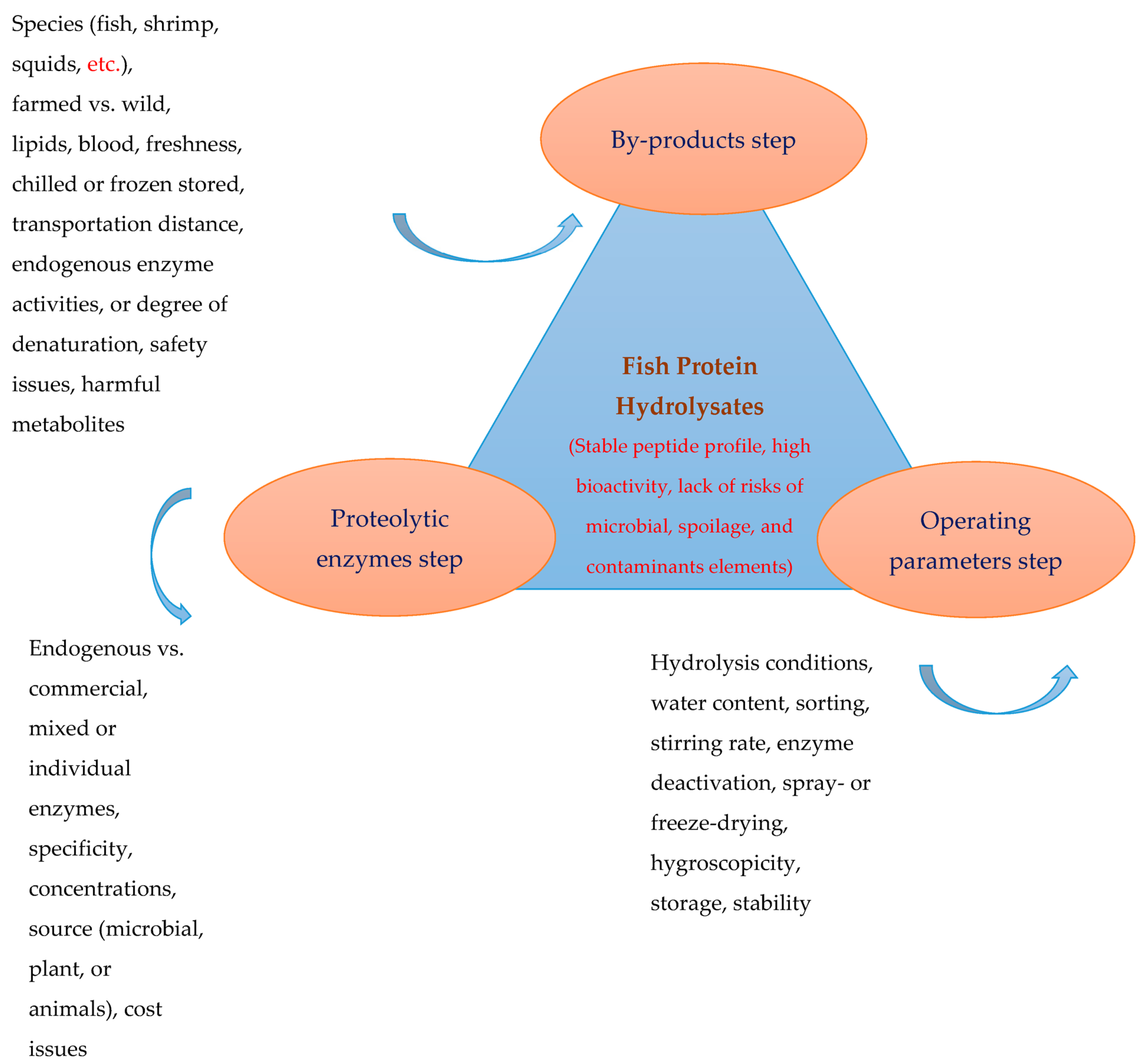

2. Fish Protein Hydrolysate: Production and Processing Factors

2.1. By-Product Composition, Quality, Storage and Handling

2.2. Proteolytic Enzymes

2.3. Operating Parameters

| Species | By-Products | Enzymes | Hydrolysis Conditions | Characteristics | Suggested Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) | Heads + frames (3:2 w/w) | Papain, ficin, bromelain, neutrase, Alcalase, Protamex, novo-proD, and thermolysin | Enzymes concentrations: 10–80 AzU/g of protein in substrate; Hydrolysis time: 10–120 min; Temperature: 40–70 °C (for thermolysin) and 30–60 °C for all other proteases; pH: 7.2 | The highest DH (71%) was obtained with ficin (80 AzU/g, 120 min, 30 °C), hydrolysates from novo-proD (5 and 25 AzU/g, 10 and 20 min) and thermolysin (25 AzU/g, 20 min) at 30 and 60 °C showed comparable emulsion activity index (EAI) and emulsion stability index (ESI) as soy protein isolate (SPI) | Alternative to soy or other proteins | [99] |

| Hake (Merluccius merluccius) | Undersize (discards) | A: endopeptidase of the serine type; P: broad-spectrum endopeptidase; T: trypsin-specific protease; C: chymotrypsin-specific protease; G: glutamic acid-specific protease, P + G | A: 1%, 50–70 °C, pH 6–9; P: 1%, 50 °C, pH 6; T: 1%, 45 °C, pH 6; C: 1%, 70 °C, pH 6; G: 1%, 50 °C, pH 6; P + G: 1% of each enzyme, 50 °C, pH 6 | Protein extraction yield: 68%, average; MW: 2.5 kDa, antioxidant activity: 88.5 mg TE/g protein obtained with endopeptidase of the serine type (A) | Food ingredient | [100] |

| Smooth hound (Mustelus mustelus) | Viscera | Neutrase®, Esperase®, Purafect®, endogenous enzymes | Purafect: pH 10.0, 50 °C; Esperase: pH 9.0, 50 °C; Neutrase: pH 7.0, 50 °C; autolysis: pH 8.0, 50 °C | The DH values of 30, 27.1, 14.2, and 6.8 were obtained using Purafect, Esperase, Endogenous enzymes, and Neutrase, respectively. Ultrafiltration (UF) fraction with MW < 5 kDa from Purafect hydrolysates showed the highest antioxidant and antihypertensive activities | Functional foods | [101] |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Frames | Properase E, pepsin, trypsin, flavourzyme, neutrase, gc106, papain | Properase E: pH 9, 50 °C, 4 h, E/S: 1:50; Pepsin: pH 2, 37 °C, 6 h, E/S: 1:50; Trypsin: pH 7.5, 45 °C, 3 h, E/S: 1:100; Flavourzyme: pH 7, 45 °C, 4 h, E/S: 1:100; Neutrase: pH 7, 45 °C, 4 h, E/S: 1:50 Gc106: pH 4.5, 45 °C, 6 h, E/S: 1:33; Papain: pH 6, 37 °C, 3 h, E/S: 1:100 | DH: 3.8–15.1; DPPH RSA: 26–70%; •OH RSA: 23.7–89%; •O2 RSA: 1.5–58.5%; H2O2 RSA: 29–72% | Functional foods | [102] |

| Anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) | Viscera | Combined Alcalase, Flavourzyme, and Protamex at a 1.1:1.0:0:9 ratio | Temperature: 50 °C pH: 7.5; Stirring: 150 rpm; Time: 3 h; E:S ration: 3% (w/w) | Glutamic cid, glycine, alanine, and lysine comprising 11.8, 10.9, 12 and 10.9 g/100 g of hydrolysates; Heavy metals (mg/kg); Cd: 0.04 Pb: 0.25 Hg: 0.02 | Nutraceuticals | [103,104] |

| Bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) | Mixture of heads, fins, and backbone | Pepsin | Enzyme concentration: 0.1 g/100 g waste mince; Hydrolysis time: 5 h; Temperature: 37 °C pH: 2.0 | Protein: 76.4%; Lipid: 10.8%; Ash: 12.2%; Moisture: 2%; Yield: 11%; DH: 39%; EAA: 25%; NEAA: 10.3%; | Aquafeed | [105] |

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | Mixture of heads, frames, and viscera | Endogenous enzymes (autolysis) | Time: 1–3 h; Temperature: 40–60 °C; pH: 7.1 (original pH of the by-products, no pH adjustment) | Peptide < 1 kDa: 93.2% at 40 °C for 1 h of autolysis; DPPH: 2.7–4.1 µM; TE/g hydrolysate HRSA: 81–98.2%; Metal chelating: 6.2–28.5 µM; EDTA/g hydrolysate | Food/feed ingredients | [59] |

| Red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) | Viscera | Alcalase | E:S ratio: 1:10 (w/w); Temperature: 59 °C; Protein concentration: 10 g/L; Stirring speed: 51 rpm; Time: 3 h | Protein: 42.2%; Lipid: 3.6%; Ash: 22.9%; EAA: 349 residue/1000 residues; HAA: 387 residue/1000 residues; Peptides with MW of 336 Da were the main fractions; ABTS RSA: 536 μM TE/g; FRAP: 115 μM TE/g; Chelation of Fe2+: 377 μM EDTA/g | Food applications | [106,107] |

| Red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) | Viscera | Alcalase | Optimal conditions: E:S ratio: 0.306 U/g; Substarte concentration: 8 g protein/L; Time: 3 h; Temperature: 60 °C; pH: 10 | DH: 42.5% Iron-binding capacity of hydrolysate (RTVH-B): 67.1%; Iron-binding capacity of <1 kDa UF fraction (FRTVH-V): 95.8% | Dietary supplements to improve iron absorption | [108] |

| Monkfish (Lophius piscatorius) | Heads, viscera | Alcalase | Optimal conditions: E:S ratio: 0.05% (v/w); Time: 3 h; Temperature: 57 °C; pH: 8.3; Stirring rate: 200 rpm | Head hydrolysate: Protein: 69.8%; Lipid: 2.4%; Ash: 18.5%; Moisture: 9.3%; Peptides < 1 kDa: 54.6%; DPPH RSA: 45%; ABTS RSA: 13.5 μg BHT/mL. Viscera hydrolysate: Protein: 67.4%; Lipid: 4.8%; Ash: 19.7%; Moisture: 5.2%; Peptides < 1 kDa: 73.7%; DPPH RSA: 49.7%; ABTS RSA: 14.5 μg BHT/mL | Protein-rich ingredient for food or feed applications | [109] |

| Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) | Heads, trimmings, frames | Alcalase | Optimal conditions: E:S ratio: 0.2% (v/w); Time: 3 h; Temperature: 64 °C; pH: 9.0; Stirring rate: 200 rpm; Solid:liquid: 1:1 | Head hydrolysate: Protein: 64.2%; Peptides < 1 kDa: 33%; Digestability: 93%; DPPH RSA: 45.3%; ABTS RSA: 13.1 μg BHT/mL. Frames + trimmings hydrolysate (S-TF): Protein: 71.1%; Peptides < 1 kDa: 48.4%; Digestability: 94.1%; DPPH RSA: 56.8%; ABTS RSA: 16.8 μg BHT/mL | Aquafeed | [16] |

| Gurnard (Trigla spp.) | Heads, skin + bone | Alcalase | Concentration: 2.5 mL/kg by-products; Time: 3 h; Temperature: 61 °C; pH: 8.6; Stirring rate: 200 rpm | Head hydrolysate: DH: 24–27%; Average MW: 1379–1626 Da; Total soluble protein: 88–94.8 g/L. Skin + bone hydrolysate: DH: 19–24%; Average MW: 1203–1562 Da; Total soluble protein: 81.9–89.2 g/L | Food and nutraceutical ingredient | [83] |

| Blue Whiting (Micromesistius poutassou) | Undersized fish | Food-grade protease of microbial origin | Fish:water ratio: 1.7–2:1; Time: 45–120 min; Temperature: 50 °C; | DH: 27–45%; Protein: 70–74%; Lipid < 0.5%; Peptides < 1 kDa: 55–78% | Anti-diabetic related functional ingredients | [110] |

| Sprat (Sprattus sprattus) | Undersized fish | Commercial SPH from BioMarine Ingredients Ireland Ltd. (Monaghan, Ireland A75 WR82, IE) | Simulated gastrointestinal digestion (SGID): Pepsin E:S ratio: 2.5% (w/w), pH 2 for 90 min at 37 °C; Pancreatin E:S ratio: 1% (w/w), pH 7 for 150 min at 37 °C | DH: 39.7%; Peptide < 1 kDa: 88.7%; EAA: 335.9; NEAA: 498.3; TAA: 834.2; Solubility > 90%; over pH range of 2–12; ORAC: 588 μM TE/g sample; FRAP: 10.9 μM TE/g sample. | Promote muscle enhancement | [111] |

| Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) | Shells and heads | Papain | Box–Behnken design (BBD) optimization: Temperature: 45–55 °C; pH: 6.5–7.5; Time: 30–90 min; E/S (%): 1–2 | DH: 46–57%; Protein: 86.2%; DPPH: 89.6%; FRAP: 2230 μmol TE/mL. CPSS: DH: 47–54%; Protein: 83.3%; DPPH: 79%; FRAP: 1380 μmol TE/mL | As a nutraceutical in the food industry | [112] |

2.4. Process Scale-Up

3. Antioxidant Activity of Fishery By-Products Protein Hydrolysates and Peptides

4. Application of Fish By-Products Protein Hydrolysates to Control Oxidative Deteriorations of Seafood

5. Conclusions and Future Challenges Facing By-Product Upgrades

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020. In Sustainability in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca9231en/CA9231EN.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Nikoo, M.; Benjakul, S.; Ahmadi Gavlighi, H. Protein hydrolysates derived from aquaculture and marine byproducts through autolytic hydrolysis. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4872–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikoo, M.; Regenstein, J.M.; Haghi Vayghan, A.; Walayat, N. Formation of oxidative compounds during enzymatic hydrolysis of byproducts of the seafood industry. Processes 2023, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassef, E.; Saleh, N.; Abde-Meguid, N.; Abdel-Mohsen, H. Utilization of fish waste biomass as a fishmeal alternative in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) diets: Effects on immuno-competence and liver and intestinal histomorphology. Int. Aquat. Res. 2023, 15, 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Noor, M.I.; Azra, M.N.; Lim, V.C.; Zaini, A.A.; Dali, F.; Hashim, I.M.; Hamzah, H.C.; Abdullah, M.F. Aquaculture research in Southeast Asia—A scientometric analysis (1990–2019). Int. Aquat. Res. 2021, 13, 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.R.; Newton, R.W.; Tlusty, M.; Little, D.C. The rise of aquaculture by-products: Increasing food production, value, and sustainability through strategic utilisation. Mar. Policy 2018, 90, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutalipassi, M.; Esposito, R.; Ruocco, N.; Viel, T.; Costantini, M.; Zupo, V. Bioactive compounds of nutraceutical value from fishery and aquaculture discards. Foods 2021, 10, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Schulte, H.; Pleissner, D.; Schönfelder, S.; Kvangarsnes, K.; Dauksas, E.; Rustad, T.; Cropotova, J.; Heinz, V.; Smetana, S. Transformation of seafood side-streams and residuals into valuable products. Foods 2023, 12, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, A.; Vázquez, J.A.; Valcarcel, J.; Mendes, R.; Bandarra, N.M.; Pires, C. Characterization of protein hydrolysates from fish discards and by-products from the North-West Spain fishing fleet as potential sources of bioactive peptides. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcorps, W.; Newton, R.W.; Sprague, M.; Glencross, B.D.; Little, D.C. Nutritional characterisation of European aquaculture processing by-products to facilitate strategic utilisation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, M.; Benjakul, S.; Ehsani, A.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Yang, N.; Xu, B.; Jin, Z.; Xu, X. Antioxidant and cryoprotective effects of a tetrapeptide isolated from Amur sturgeon skin gelatin. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 7, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yu, H.; Wei, H.; Xing, Q.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, J. Antioxidative peptides of hydrolysate prepared from fish skin gelatin using ginger protease activate antioxidant response element-mediated gene transcription in IPEC-J2 cells. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 51, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, N.T.P.; Hsu, J.L. Bioactive peptides: An understanding from current screening methodology. Processes 2022, 10, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, S.A.; Pintado, M.E. Bioactive peptides derived from marine sources: Biological and functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 348–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opheim, M.; Šližytė, R.; Sterten, H.; Provan, F.; Larssen, E.; Kjos, N.P. Hydrolysis of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) rest raw materials—Effect of raw material and processing on composition, nutritional value, and potential bioactive peptides in the hydrolysates. Process. Biochem. 2015, 50, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.A.; Sotelo, C.G.; Sanz, N.; Pérez-Martín, R.I.; Rodríguez-Amado, I.; Valcarcel, J. Valorization of aquaculture by-products of salmonids to produce enzymatic hydrolysates: Process optimization, chemical characterization and evaluation of bioactives. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.A.; Pedreira, A.; Durán, S.; Cabanelas, D.; Souto-Montero, P.; Martínez, P.; Mulet, M.; Pérez-Martín, R.I.; Valcarcel, J. Biorefinery for tuna head wastes: Production of protein hydrolysates, high-quality oils, minerals and bacterial peptones. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 357, 131909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, M.; Xu, X.; Regenstein, J.M.; Noori, F. Autolysis of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) processing by-products: Enzymatic activities, lipid and protein oxidation, and antioxidant activity of hydrolysates. Food Biosci. 2021, 39, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcarcel, J.; Sanz, N.; Vázquez, J.A. Optimization of the enzymatic protein hydrolysis of by-products from seabream (Sparus aurata) and seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax), chemical and functional characterization. Foods 2020, 9, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.M.; Yang, X.R.; Chi, C.F.; Wang, B. Gelatins and antioxidant peptides from Skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) skins: Purification, characterization, and cytoprotection on ultraviolet-A injured human skin fibroblasts. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.H.; Kim, S.K. Marine bioactive peptides as potential antioxidants. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2013, 14, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Q. Production and antioxidant properties of marine-derived bioactive peptides. In Marine Proteins and Peptides: Biological Activities and Applications; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Forero, A.; Medina-Lambraño, K.; Acosta-Ortíz, E. Variations in the proximate composition of the sea cucumber, Isostichopus sp. aff badionotus. Int. Aquat. Res. 2021, 13, 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Aluko, R.E. Amino acids, peptides, and proteins as antioxidants for food preservation. In Handbook of Antioxidants for Food Preservation; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015; pp. 105–140. [Google Scholar]

- Nikoo, M.; Benjakul, S. Potential application of seafood-derived peptides as bifunctional ingredients, antioxidant–cryoprotectant: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiwong, S.; Autsavapromporn, N.; Siriwoharn, T.; Techapun, C.; Wangtueai, S. Enzymatic hydrolysis optimization for preparation of sea cucumber (Holothuria scabra) hydrolysate with an antiproliferative effect on the HepG2 liver cancer cell line and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Liang, J.; Xiao, G.; Vargas-De-La-Cruz, C.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Q. Active sites of peptides Asp-Asp-Asp-Tyr and Asp-Tyr-Asp-Asp protect against cellular oxidative stress. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.; Wu, N.; Tang, S.; Xiao, N.; Jiang, Y.; Tu, Y.; Xu, M. Industrial application of protein hydrolysates in food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 1788–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, C.; Horn, A.F.; Sørensen, A.D.M.; Farvin, K.S.; Nielsen, N.S. Antioxidative strategies to minimize oxidation in formulated food systems containing fish oils and omega-3 fatty acids. In Antioxidants and Functional Components in Aquatic Foods; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez, M.; Xiong, Y. Protein oxidation in foods: Mechanisms, consequences, and antioxidant solutions. Foods 2021, 10, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.B.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.M.; Chi, C.F.; Wang, B. Eight collagen peptides from hydrolysate fraction of Spanish mackerel skins: Isolation, identification, and in vitro antioxidant activity evaluation. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, X.; Zhuang, Y. Purification and characterization of novel antioxidant peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) skin gelatin. Peptides 2012, 38, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.H.; Qian, Z.J.; Ryu, B.; Park, J.W.; Kim, S.K. In vitro antioxidant activity of a peptide isolated from Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) scale gelatin in free radical-mediated oxidative systems. J. Funct. Foods 2010, 2, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Antiphotoaging effect and purification of an antioxidant peptide from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) gelatin peptides. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingtong, L.; Yongliang, Z.; Liping, S. Identification and characterization of the peptides with calcium-binding capacity from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) skin gelatin enzymatic hydrolysates. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.F.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.M.; Zhang, B.; Deng, S.G. Isolation and characterization of three antioxidant peptides from protein hydrolysate of bluefin leatherjacket (Navodon septentrionalis) heads. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.H.; Luo, Q.B.; Pan, X.; Chi, C.F.; Sun, K.L.; Wang, B. Preparation, identification, and activity evaluation of ten antioxidant peptides from protein hydrolysate of swim bladders of miiuy croaker (Miichthys miiuy). J. Funct. Foods 2018, 47, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovissipour, M.; Rasco, B.; Shiroodi, S.G.; Modanlow, M.; Gholami, S.; Nemati, M. Antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysates from whole anchovy sprat (Clupeonella engrauliformis) prepared using endogenous enzymes and commercial proteases. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero-Pino, F.; Espejo-Carpio, F.J.; Guadix, E.M. Production and identification of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitory peptides from discarded Sardine pilchardus protein. Food Chem. 2020, 328, 127096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiodza, K.; Goosen, N.J. Evaluation of handling and storage stability of spray dried protein hydrolysates from sardine (Sardina pilchardus) processing by-products: Effect of enzymatic hydrolysis time, spray drying temperature and maltodextrin concentration. Food Bioprod. Process. 2023, 141, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, M.; Benjakul, S.; Yasemi, M.; Gavlighi, H.A.; Xu, X. Hydrolysates from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) processing by-product with different pretreatments: Antioxidant activity and their effect on lipid and protein oxidation of raw fish emulsion. Lwt 2019, 108, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Hu, X. Structural characteristics and stability of salmon skin protein hydrolysates obtained with different proteases. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 153, 112460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczewska, J.; Kulawik, P.; Jamróz, E.; Čagalj, M.; Matas, R.F.; Šimat, V. Valorization of prawn/shrimp shell waste through the production of biologically active components for functional food purposes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 104, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Portilla, D.; Martínez, R.; Bernal, C. Valorization of shrimp (Heterocarpus reedi) processing waste via enzymatic hydrolysis: Protein extractions, hydrolysates and antioxidant peptide fractions. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 48, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; He, C.; Wei, H.; Wu, G.; Xiong, H.; Ma, Y. Fractionation and purification of antioxidant peptides from abalone viscera by a combination of Sephadex G-15 and Toyopearl HW-40F chromatography. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, L.; Chi, C.F.; Ma, J.H.; Luo, H.Y.; Xu, Y.F. Purification and characterisation of a novel antioxidant peptide derived from blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) protein hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Ahn, C.B.; Je, J.Y. Partial purification and identification of three antioxidant peptides with hepatoprotective effects from blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) hydrolysate by peptic hydrolysis. J Funct. Foods 2016, 20, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, E.; Rajapakse, N.; Byun, H.G.; Kim, S.K. Investigation of jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas) skin gelatin peptides for their in vitro antioxidant effects. Life Sci. 2005, 77, 2166–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukkhown, P.; Jangchud, K.; Lorjaroenphon, Y.; Pirak, T. Flavored-functional protein hydrolysates from enzymatic hydrolysis of dried squid by-products: Effect of drying method. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 76, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavandi, A.; Hu, Z.; Teh, S.; Zhao, J.; Carne, A.; Bekhit, A.; Bekhit, A.E.D.A. Antioxidant and functional properties of protein hydrolysates obtained from squid pen chitosan extraction effluent. Food Chem. 2017, 227, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufi-Kechaou, E.; Derouiniot-Chaplin, M.; Amar, R.B.; Jaouen, P.; Berge, J.P. Recovery of valuable marine compounds from cuttlefish by-product hydrolysates: Combination of enzyme bioreactor and membrane technologies: Fractionation of cuttlefish protein hydrolysates by ultrafiltration: Impact on peptidic populations. C. R. Chim. 2017, 20, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudennec, B.; Balti, R.; Ravallec, R.; Caron, J.; Bougatef, A.; Dhulster, P.; Nedjar, N. In vitro evidence for gut hormone stimulation release and dipeptidyl-peptidase IV inhibitory activity of protein hydrolysate obtained from cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) viscera. Food Res. Int. 2015, 78, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kchaou, H.; Jridi, M.; Benbettaieb, N.; Debeaufort, F.; Nasri, M. Bioactive films based on cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) skin gelatin incorporated with cuttlefish protein hydrolysates: Physicochemical characterization and antioxidant properties. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 24, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarteshnizi, R.A.; Sahari, M.A.; Gavlighi, H.A.; Regenstein, J.M.; Nikoo, M. Antioxidant activity of Sind sardine hydrolysates with pistachio green hull (PGH) extracts. Food Biosci. 2019, 27, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, S.A.; Emire, S.A.; Barea, P.; Illera, A.E.; Melgosa, R.; Beltrán, S.; Sanz, M.T. Valorisation of low-valued ray-finned fish (Labeobarbus nedgia) by enzymatic hydrolysis to obtain fish-discarded protein hydrolysates as functional foods. Food Bioprod. Process. 2023, 141, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, A. Salmon By-Product Proteins; FAO Fisheries Circular No. 1027; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shumilina, E.; Slizyte, R.; Mozuraityte, R.; Dykyy, A.; Stein, T.A.; Dikiy, A. Quality changes of salmon by-products during storage: Assessment and quantification by NMR. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Hyldig, G.; Sørensen, A.D.M.; Sørensen, R.; Iñarra, B.; Chastagnol, C.B.; Gutierrez, M.; San Martin, D.; Simonsen, A.; Dam, L.; et al. Hurdles and Bottlenecks in Maintaining and Value Adding of Seafood Side-Streams. Waseabi. 2020, pp. 1–45, Grant agreement No 837726. Available online: https://www.waseabi.eu/media/zq5mau35/waseabi-deliverable-d1-1_industry_version-1-2_april-2021.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Nikoo, M.; Regenstein, J.M.; Noori, F.; Gheshlaghi, S.P. Autolysis of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) by-products: Enzymatic activities, lipid and protein oxidation, and antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysates. LWT 2021, 140, 110702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffree, R.A.; Warnau, M.; Teyssié, J.L.; Markich, S.J. Comparison of the bioaccumulation from seawater and depuration of heavy metals and radionuclides in the spotted dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula (Chondrichthys) and the turbot Psetta maxima (Actinopterygii: Teleostei). Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 368, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bat, L.; Yardım, Ö.; Öztekin, A.; Arıcı, E. Assessment of heavy metal concentrations in Scophthalmus maximus (Linnaeus, 1758) from the Black Sea coast: Implications for food safety and human health. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 12, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ghirmai, S.; Undeland, I. Stabilization of herring (Clupea harengus) by-products against lipid oxidation by rinsing and incubation with antioxidant solutions. Food Chem. 2022, 316, 126337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Forghani, B.; Abdollahi, M.; Undeland, I. Five cuts from herring (Clupea harengus): Comparison of nutritional and chemical composition between co-product fractions and fillets. Food Chem. X 2022, 16, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Wei, S.; Sun, Q.; Xia, Q.; Shi, W.; Ji, H.; Liu, S. Comparison of the proximate composition and nutritional profile of byproducts and edible parts of five species of shrimp. Foods 2021, 10, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.P.; Davis, D.A.; Boyd, C.E. A preliminary survey of antibiotic residues in frozen shrimp from retail stores in the United States. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Mansour, S.T.; Nouh, R.A.; Khattab, A.R. Crustaceans (shrimp, crab, and lobster): A comprehensive review of their potential health hazards and detection methods to assure their biosafety. J. Food Saf. 2023, 43, e13026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Cai, Q.; Ying, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Murk, T.A. Health risk assessment of arsenic and some heavy metals in the edible crab (Portunus trituberculatus) collected from Hangzhou Bay, China. Mar. Poll. Bull. 2021, 173, 113007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T. Biorefinery Process Development for Recovery of Functional and Bioactive Compounds from Lobster Processing By-Products for Food and Nutraceutical Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Flinders University, School of Health Sciences, Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- USDA. Squid and Squid Byproducts-Agricultural Marketing Service. Teaching Evaluation Report. 2016; pp. 1–31, Compiled by USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service, Agricultural Analytics Division for the USDA National Organic Program. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Squid-TR-011216.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Sierra Lopera, L.M.; Sepúlveda Rincón, C.T.; Vásquez Mazo, P.; Figueroa Moreno, O.A.; Zapata Montoya, J.E. Byproducts of aquaculture processes: Development and prospective uses. Review. Vitae 2018, 25, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souissi, N.; Ellouz-Triki, Y.; Bougatef, A.; Blibech, M.; Nasri, M. Preparation and use of media for protease-producing bacterial strains based on by-products from cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) and wastewaters from marine-products processing factories. Microbiol. Res. 2008, 163, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Bihan, E.; Perrin, A.; Koueta, N. Effect of different treatments on the quality of cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis L.) viscera. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, G.Y.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, Y.W.; Lee, Y.B. Development of refined cuttlefish (Todarodes pacificus) oil and its use as functional ingredients. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 20, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaviz-Villa, I.; Lango-Reynoso, F.; Espejo, I.A.A. Risks and critical points of the oyster product system. Glob. J. Biol. Agric. Health Sci. 2015, 4, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, C.; Tamura, S.; Tohse, R.; Fujita, S.; Kikuchi, M.; Asada, C.; Nakamura, Y. Isolation and identification of an angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptide from pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata) shell protein hydrolysate. Process. Biochem. 2019, 77, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulagesan, S.; Krishnan, S.; Nam, T.J.; Choi, Y.H. A review of bioactive compounds in oyster shell and tissues. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 913839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, R.; Abdelhedi, O.; Nasri, M.; Jridi, M. Fermented protein hydrolysates: Biological activities and applications. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, B.K.; Nollet, L.M.; Toldrá, F.; Benjakul, S.; Paliyath, G.; Hui, Y.H. (Eds.) Food Biochemistry and Food Processing; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Klomklao, S.; Benjakul, S.; Simpson, B.K. Seafood enzymes: Biochemical properties and their impact on quality. In Food Biochemistry and Food Processing; Simpson, B.K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kuepethkaew, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kishimura, H.; Kumagai, Y.; Simpson, B.K.; Benjakul, S.; Damodaran, S.; Klomklao, S. Enzymological characteristics of pepsinogens and pepsins purified from lizardfish (Saurida micropectoralis) stomach. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalinanon, S.; Benjakul, S.; Kishimura, H.; Osako, K. Type I collagen from the skin of ornate threadfin bream (Nemipterus hexodon): Characteristics and effect of pepsin hydrolysis. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Lee, C.C.; Ashaolu, J.O.; Tarhan, O.; Pourjafar, H.; Jafari, S.M. Pepsin: An excellent proteolytic enzyme for the production of bioactive peptides. Food. Rev. Int. 2023, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.A.; Valcarcel, J.; Sapatinha, M.; Bandarra, N.M.; Mendes, R.; Pires, C. Effect of the season on the production and chemical properties of fish protein hydrolysates and high-quality oils obtained from gurnard (Trigla spp.) by-products. LWT 2023, 177, 114576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspevik, T.; Thoresen, L.; Steinsholm, S.; Carlehög, M.; Kousoulaki, K. Sensory and chemical properties of protein hydrolysates based on mackerel (Scomber scombrus) and salmon (Salmo salar) side stream materials. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2021, 30, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, M.A.; Howieson, J.; Fotedar, R.; Partridge, G.J. Enzymatic fish protein hydrolysates in finfish aquaculture: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Tu, Z. A comprehensive review of the control and utilization of animal aquatic products by autolysis-based processes: Mechanism, process, factors, and application. Food Res. Int. 2022, 164, 112325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Z.Q.; Li, D.Y.; Yu, M.M.; Liu, Y.X.; Qin, L.; Zhou, D.-Y.; Shahidi, F.; Zhu, B.W. Action of endogenous proteases on texture deterioration of the bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) adductor muscle during cold storage and its mechanism. Food Chem. 2020, 323, 126790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Zhou, D.Y.; Liu, Y.X.; Yu, M.M.; Liu, B.; Song, L.; Dong, X.-P.; Qi, H.; Shahidi, F. Inhibitory effect of natural metal ion chelators on the autolysis of sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus) and its mechanism. Food Res. Int. 2020, 133, 109205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C.; Teixeira, B.; Cardoso, C.; Mendes, R.; Nunes, M.L.; Batista, I. Cape hake protein hydrolysates prepared from alkaline solubilised proteins pre-treated with citric acid and calcium ions: Functional properties and ACE inhibitory activity. Process. Biochem. 2015, 50, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Abdollahi, M.; Alminger, M.; Undeland, I. Cross-processing herring and salmon co-products with agricultural and marine side-streams or seaweeds produces protein isolates more stable towards lipid oxidation. Food Chem. 2022, 382, 132314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irankunda, R.; Camaño Echavarría, J.A.; Paris, C.; Stefan, L.; Desobry, S.; Selmeczi, K.; Muhr, L.; Canabady-Rochelle, L. Metal-chelating peptides separation using immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography: Experimental methodology and simulation. Separations 2022, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.L.; Gao, M.; Wang, Y.Z.; Li, X.R.; Wang, P.; Wang, B. Antioxidant peptides from protein hydrolysate of marine red algae Eucheuma cottonii: Preparation, identification, and cytoprotective mechanisms on H2O2 oxidative damaged HUVECs. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 791248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remme, J.; Tveit, G.M.; Toldnes, B.; Slizyte, R.; Carvajal, A.K. Production of protein hydrolysates from cod (Gadus morhua) heads: Lab and pilot scale studies. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2022, 31, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zuo, X.; Luo, X.; Chen, Z.; Cao, W.; Lin, H.; Qin, X.; Wu, L.; Zheng, H. Functional, physicochemical, and structural properties of the hydrolysates derived from the abalone (Haliotis discus subsp hannai Ino) foot muscle proteins. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Fuente, B.; Pallarés, N.; Berrada, H.; Barba, F.J. Salmon (Salmo salar) side streams as a bioresource to obtain potential antioxidant peptides after applying pressurized liquid extraction (PLE). Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šližytė, R.; Rustad, T.; Storrø, I. Enzymatic hydrolysis of cod (Gadus morhua) by-products: Optimization of yield and properties of lipid and protein fractions. Process. Biochem. 2005, 40, 3680–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Morioka, K.; Itoh, Y.; Obatake, A. Contribution of lipid oxidation to bitterness and loss of free amino acids in the autolytic extract from fish wastes: Effective utilization of fish wastes. Fish. Sci. 2000, 66, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Huang, J.; Woo, M.W.; Hu, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhao, Q. Effect of cold and hot enzyme deactivation on the structural and functional properties of rice dreg protein hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chang, S.K.; Meng, S. Comparing the kinetics of the hydrolysis of by-product from channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) fillet processing by eight proteases. LWT 2019, 111, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñarra, B.; Bald, C.; Gutierrez, M.; San Martin, D.; Zufía, J.; Ibarruri, J. Production of bioactive peptides from hake by-catches: Optimization and scale-up of enzymatic hydrolysis process. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhedi, O.; Mora, L.; Jridi, M.; Toldrá, F.; Nasri, M. Proteolysis coupled with membrane separation for the isolation of bioactive peptides from defatted smooth hound byproduct proteins. Waste Biomass Valori. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; He, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Sun, L. Purification and identification of antioxidant peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) frame protein. Molecules 2012, 17, 12836–12850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangano, V.; Gervasi, T.; Rotondo, A.; De Pasquale, P.; Dugo, G.; Macrì, F.; Salvo, A. Protein hydrolysates from anchovy waste: Purification and chemical characterization. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannetto, A.; Esposito, E.; Lanza, M.; Oliva, S.; Riolo, K.; Di Pietro, S.; Abbate, J.M.; Briguglio, G.; Cassata, G.; Cicero, L.; et al. Protein hydrolysates from anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) waste: In vitro and in vivo biological activities. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Rady, T.K.; Tahoun, A.A.M.; Abdin, M.; Amin, H.F. Effect of different hydrolysis methods on composition and functional properties of fish protein hydrolysate obtained from bigeye tuna waste. Int. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 6552–6562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, C.T.; Zapata, J.E. Effects of enzymatic hydrolysis conditions on the antioxidant activity of red Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) viscera hydrolysates. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, C.T.; Zapata, J.E.; Martínez-Álvarez, O.; Alemán, A.; Montero, M.P.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C. The preferential use of a soy-rapeseed lecithin blend for the liposomal encapsulation of a tilapia viscera hydrolysate. LWT 2021, 139, 110530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.J.; Gómez, N.A.; Zapata, J.E.; López-García, G.; Cilla, A.; Alegría, A. Optimization of the red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) viscera hydrolysis for obtaining iron-binding peptides and evaluation of in vitro iron bioavailability. Foods 2020, 9, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.A.; Menduíña, A.; Nogueira, M.; Durán, A.I.; Sanz, N.; Valcarcel, J. Optimal production of protein hydrolysates from monkfish by-products: Chemical features and associated biological activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnedy-Rothwell, P.A.; Khatib, N.; Sharkey, S.; Lafferty, R.A.; Gite, S.; Whooley, J.; O’Harte, F.P.; FitzGerald, R.J. Physicochemical, nutritional and in vitro antidiabetic characterisation of blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou) protein hydrolysates. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekoohi, N.; Naik, A.S.; Amigo-Benavent, M.; Harnedy-Rothwell, P.A.; Carson, B.P.; FitzGerald, R.J. Physicochemical, technofunctional, in vitro antioxidant, and in situ muscle protein synthesis properties of a sprat (Sprattus sprattus) protein hydrolysate. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1197274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayakar, B.; Xavier, K.M.; Ngasotter, S.; Layana, P.; Balange, A.K.; Priyadarshini, B.; Nayak, B.B. Characterization of spray-dried carotenoprotein powder from Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) shells and head waste extracted using papain: Antioxidant, spectroscopic, and microstructural properties. LWT 2022, 159, 113188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, A.; Rustad, T.; Cusimano, G.M. Tuna sidestream valorization: A circular blue bioeconomy approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, R.J.; Kellerby, S.S.; Decker, E.A. Antioxidant activity of proteins and peptides. Crit. Rew. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončar, A.; Negrojević, L.; Dimitrić-Marković, J.; Dimić, D. The reactivity of neurotransmitters and their metabolites towards various nitrogen-centered radicals: Experimental, theoretical, and biotoxicity evaluation. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2021, 95, 107573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Zhong, Y. Measurement of antioxidant activity. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 757–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamdad, F.; Shin, S.H.; Suh, J.W.; Nimalaratne, C.; Sunwoo, H. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of casein hydrolysate produced using high hydrostatic pressure combined with proteolytic enzymes. Molecules 2017, 22, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basilicata, M.G.; Pepe, G.; Adesso, S.; Ostacolo, C.; Sala, M.; Sommella, E.; Scala, M.C.; Messore, A.; Autore, G.; Marzocco, S.; et al. Antioxidant properties of buffalo-milk dairy products: A β-Lg peptide released after gastrointestinal digestion of buffalo ricotta cheese reduces oxidative stress in intestinal epithelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandomenico, A.; Severino, V.; Apone, F.; De Lucia, A.; Caporale, A.; Doti, N.; Russo, A.; Russo, R.; Rega, C.; Del Giacco, T.; et al. Trifluoroacetylated tyrosine-rich D-tetrapeptides have potent antioxidant activity. Peptides 2017, 89, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzapour-Kouhdasht, A.; Moosavi-Nasab, M.; Lee, C.W.; Yun, H.; Eun, J.B. Structure–function engineering of novel fish gelatin-derived multifunctional peptides using high-resolution peptidomics and bioinformatics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Dong, L.; Bao, Z.; Lin, S. C-terminal modification on the immunomodulatory activity, antioxidant activity, and structure–activity relationship of pulsed electric field (PEF)-treated pine nut peptide. Foods 2022, 11, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Ju, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lin, S. Effect of self-assembling peptides on its antioxidant activity and the mechanism exploration. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 125, 109258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davalos, A.; Miguel, M.; Bartolome, B.; Lopez-Fandino, R. Antioxidant activity of peptides derived from egg white proteins by enzymatic hydrolysis. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 1939–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wu, G.; Yang, J.; He, C.; Xiong, H.; Ma, Y. Abalone visceral peptides containing Cys and Tyr exhibit strong in vitro antioxidant activity and cytoprotective effects against oxidative damage. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, H.; Su, G.; Zhao, M. Structure–activity relationship of antioxidant dipeptides: Dominant role of Tyr, Trp, Cys and Met residues. J. Funct. Foods. 2016, 21, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.L.; Ning, P.; Jiao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Cheng, Y.H. Extraction of antioxidant peptides from rice dreg protein hydrolysate via an angling method. Food Chem. 2022, 337, 128069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, T.; Li, X.; Sadiq, F.A.; Mao, K.; Gao, J.; Mi, S.; Liu, X.; Deng, W.; Chitrakar, B.; Sang, Y. Novel antioxidant peptides from protein hydrolysates of scallop (Argopecten irradians) mantle using enzymatic and microbial methods: Preparation, purification, identification and characterization. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 164, 113636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Qiu, Y.T.; Wang, Y.M.; Chi, C.F.; Wang, B. Novel antioxidant collagen peptides of Siberian sturgeon (Acipenser baerii) cartilages: The preparation, characterization, and cytoprotection of H2O2-damaged human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, T.B.; He, T.P.; Li, H.B.; Tang, H.W.; Xia, E.Q. The structure-activity relationship of the antioxidant peptides from natural proteins. Molecules 2016, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Hu, X.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Yang, S. Preparation, purification and identification of iron-chelating peptides derived from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) skin collagen and characterization of the peptide-iron complexes. LWT 2021, 149, 111796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Ma, R.; Liu, X.; Xie, Y.; Chen, J. Highly effective peptide-calcium chelate prepared from aquatic products processing wastes: Stickwater and oyster shells. LWT 2022, 168, 113947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Ge, X.; Hao, J.; Wu, T.; Liu, R.; Sui, W.; Geng, J.; Zhang, M. Identification of high iron–chelating peptides with unusual antioxidant effect from sea cucumbers and the possible binding mode. Food Chem. 2023, 399, 133912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Effects of multi-frequency ultrasound on the freezing rates, quality properties and structural characteristics of cultured large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, X.; Hong, H. Evidence of myofibrillar protein oxidation and degradation induced by exudates during the thawing process of bighead carp fillets. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saki, N.; Ghaffari, M.; Nikoo, M. Effect of active ice nucleation bacteria on freezing and the properties of surimi during frozen storage. LWT 2023, 176, 114548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Roy, K.; Pan, J.; Mraz, J. Icy affairs: Understanding recent advancements in the freezing and frozen storage of fish. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1383–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikoo, M.; Benjakul, S.; Rahmanifarah, K. Hydrolysates from marine sources as cryoprotective substances in seafoods and seafood products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 57, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Majura, J.J.; Liu, L.; Cao, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, G.; Gao, J.; Zheng, H.; Lin, H. The cryoprotective activity of tilapia skin collagen hydrolysate and the structure elucidation of its antifreeze peptide. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 179, 114670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, K.; Liu, L.; He, L.; Qi, X.; Yang, H. Cryoprotective effect of collagen hydrolysates from squid skin on frozen shrimp and characterizations of its antifreeze peptides. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 174, 114443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuepethkaew, S.; Klomklao, S.; Benjakul, S.; Betti, M.; Simpson, B.K. Assessment of gelatin hydrolysates from threadfin bream (Nemipterus hexodon) skin as a cryoprotectant for denaturation prevention of threadfin bream natural actomyosin subjected to different freeze-thaw cycles. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 143, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J. Dual cryoprotective and antioxidant effects of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) protein hydrolysates on unwashed surimi stored at conventional and ultra-low frozen temperatures. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 153, 112563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.J.; Wang, F.X.; Yu, J.; Li, X.H.; Liu, Y.L. Cryoprotective effects of protein hydrolysates prepared from by-products of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) on freeze-thawed surimi. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Cao, S.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, B.; Chen, H.; Tu, M.; Tan, Z.; Du, M.; Li, T. Characterization and the mechanism underlying the cryoprotective activity of a peptide from large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea). Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Rocha, M.; Alemán, A.; Romani, V.P.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Montero, P.; Prentice, C. Effects of agar films incorporated with fish protein hydrolysate or clove essential oil on flounder (Paralichthys orbignyanus) fillets shelf-life. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 81, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamróz, E.; Kulawik, P.; Tkaczewska, J.; Guzik, P.; Zając, M.; Juszczak, L.; Krzyściak, P.; Turek, K. The effects of active double-layered furcellaran/gelatin hydrolysate film system with Ala-Tyr peptide on fresh Atlantic mackerel stored at −18 °C. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 127867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkaczewska, J.; Bukowski, M.; Mak, P. Identification of antioxidant peptides in enzymatic hydrolysates of carp (Cyprinus carpio) skin gelatin. Molecules 2018, 24, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padial-Domínguez, M.; Espejo-Carpio, F.J.; García-Moreno, P.J.; Jacobsen, C.; Guadix, E.M. Protein derived emulsifiers with antioxidant activity for stabilization of omega-3 emulsions. Food Chem. 2020, 329, 127148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Hong, H.; Luo, Y. Prevention of protein oxidation and enhancement of gel properties of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) surimi by addition of protein hydrolysates derived from surimi processing by-products. Food Chem. 2020, 316, 126343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shan, Y.; Hong, H.; Luo, Y.; Hong, X.; Ye, W. Prevention of protein and lipid oxidation in freeze-thawed bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) fillets using silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) fin hydrolysates. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 123, 109050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Ding, H.; Chen, K.; Lu, T.; Dai, Z. Study on the mechanism of protein hydrolysate delaying quality deterioration of frozen surimi. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 167, 113767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Yuan, C.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Inhibition mechanism of membrane-separated silver carp hydrolysates on ice crystal growth obtained through experiments and molecular dynamics simulation. Food Chem. 2023, 414, 135695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Hong, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Luo, Y. Antioxidant and cryoprotective effects of hydrolysate from gill protein of bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) in preventing denaturation of frozen surimi. Food Chem. 2019, 298, 124868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczewska, J.; Kulawik, P.; Jamróz, E.; Guzik, P.; Zając, M.; Szymkowiak, A.; Turek, K. One-and double-layered furcellaran/carp skin gelatin hydrolysate film system with antioxidant peptide as an innovative packaging for perishable foods products. Food Chem. 2021, 351, 129347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkelunas, P.J.; Li-Chan, E.C. Production and assessment of Pacific hake (Merluccius productus) hydrolysates as cryoprotectants for frozen fish mince. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Nilsuwan, K.; Ma, L.; Benjakul, S. Effect of liposomal encapsulation and ultrasonication on debittering of protein hydrolysate and plastein from salmon frame. Foods 2023, 12, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, S.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, M. Encapsulation of oyster protein hydrolysates in nanoliposomes: Vesicle characteristics, storage stability, in vitro release, and gastrointestinal digestion. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Xie, Y.; Huang, X.; Cheng, C.; McClements, D.J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Zou, L.; Wei, L. Encapsulation of bitter peptides in diphasic gel double emulsions: Bitterness masking, sustained release and digestion stability. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, X.; McClements, D.J.; Cheng, C.; Xie, Y.; Liang, R.; Liu, J.; Zou, L.; Liu, W. Encapsulation of bitter peptides in water-in-oil high internal phase emulsions reduces their bitterness and improves gastrointestinal stability. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Yield (%) of By-Products in Relation to Whole Weight | By-Products Fractions and Yield (%) | Proximate Composition (%) | Main Safety Issues | Preventive Measures | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | ||||||

| Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) | 43.8 | Heads (9.9), viscera (10.6), frames (10.4), trimmings (8.2), skin + scale (4.2) | Heads: moisture (53.2), ash (5.01), protein (17.2), lipid (21.5) Frames: moisture (52.9), ash (6.5), protein (19.3), lipid (17.16) Trimmings: moisture (46.4), ash (2.2), protein (18.1), lipid (26.4) Viscera: moisture (46.5), ash (0.97), protein (12.4), lipid (37) | Fast decomposition by endogenous proteolysis, gills and viscera blood, gall bladder, off-odor of viscera, formation of harmful compounds such as biogenic amines and trimethylamine (TMA), loss of freshness | Lowering storage time and temperature; sorting heads, frames from viscera; removal of gills where possible | [10,15,56,57] |

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | 20–30 | Heads (11.2), viscera (7.8), frames (7.6), skin (3.4) | Heads: moisture (69.6) organic matter (27.7), ash (2.7) Trimmings + Frames: moisture (66.5) organic matter (30.6), ash (3) | Fast decomposition by endogenous proteolysis (autolysis), high abdominal fats, blood (gills), non-digested feed in the stomach, digesta and fecal matter in the intestines | Cold or frozen storage of by-products, sorting heads and viscera, maintaining freshness, where possible removal of gills with large amounts of blood and hemoglobin (e.g., in large fish > 2 kg), pretreatment with antioxidants | [16,58,59] |

| Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus albacares) | 50–55 | Heads (13), fins (1), skin (10), bone (6), viscera (8), dark meat | Upper half: moisture (68.2), organic matter (26.1), ash (5.4) Lower half: moisture (60.6), organic matter (25.1), ash (14) | Long traveling times post-catch to processing plant; degradation and off-odor of viscera; spoilage of gills, tongue, and head flesh; huge blood release from large gills; activation of muscle proteases of heads (autolysis of proteins); contamination by heavy metals (e.g., cadmium) | Using fresh by-products (caught by longline), removal of gills (blood), cold or frozen storage of by-product before hydrolysis, sorting of viscera from heads, reject batch with high heavy metals | [17] |

| Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) | 69.6 | Heads (19.6), frames (16.4) trimmings (13.5), viscera (14.3), skin + scale (5.8) | Heads: moisture (71.3), ash (6.4), protein (20.2), lipid (1.7) Frames: moisture (58.7), ash (7.9), protein (19.1), lipid (12.1) Trimmings: moisture (70.1), ash (4.3), protein (20), lipid (4.8) Viscera: moisture (70.9), ash (1.6), protein (13.4), lipid (10.9) | Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in muscle and by-products, autolysis of by-products, long time-period from catch to delivery at the dock, low freshness, bacterial spoilage | Inhibiting quality deterioration by low storage time and temperature, sorting by-products fractions, reject batch with high heavy metals | [10,60,61] |

| European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) | 55 | Heads (21.2), frames (11.9) trimmings (7.1), viscera (7.7), skin + scale (7) | Heads: moisture (59.4), ash (10.1), protein (17.8), lipid (11.2) Frames: moisture (52.6), ash (12.4), protein (18.6), lipid (13.9) Trimmings: moisture (57.5), ash (6.9), protein (21.2), lipid (11.1) Viscera: moisture (31.9), ash (1.5), protein (14.34), lipid (39.3) | Significant amount of oil and thus high lipid oxidation during hydrolysis, addition of lipid-derived carbonyls on the forming peptides, viscera spoilage, freshness | Sorting frames and trimmings from viscera, antioxidants addition, using N2 to control possible oxidation with viscera | [10,19] |

| Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) | 59.9 | Heads (27.6), frames (12.4) trimmings (6), viscera (6.9), skin + scale (7) | Heads: moisture (51.9), ash (8), protein (15.3), lipid (20.3) Frames: moisture (55.6), ash (9.4), protein (19.4), lipid (13.7) Trimmings: moisture (56.5), ash (4.4), protein (22.4), lipid (13.2) Viscera: moisture (60.5), ash (2), protein (17.2), lipid (12.8) | Significant amount of oil and thus high lipid oxidation during hydrolysis, addition of lipid-derived carbonyls on the forming peptides, viscera spoilage, freshness | Sorting frames and trimmings from viscera, antioxidants addition, using N2 to control possible oxidation with viscera | [10,19] |

| Herring (Clupea harengus) | ~60 | Heads (13.7–17), backbone (12.1–24.6), belly flap (4.5–10.7), tail (1.6–4), others (including viscera, blood, roe, milt, etc., depending on catch season, 2.4–17.6) | Protein (12.8–19.2), lipids (5.8–17.6), ash (1.3–7.2), moisture (65.7–78.7) | Fast oxidative deterioration, rancidity soon after filleting, blood contamination (Hb-mediated lipid oxidation), autolysis, rapid microbial spoilage, loss of freshness (biogenic amines formation) | Low storage temperature, stabilization by antioxidants, sorting of heads (due to presence of gills and blood) with other more stable fractions | [62,63] |

| Crustaceans | ||||||

| Shrimp (Litopenaeus sp., Macrobrachium sp., Fenneropenaeus sp., Penaeus spp.) | 44–62.5 | Heads (34–54), shell (7.4–7.6), tail (1.7–2.8) | Head: moisture (68–75), protein (6.6–10), lipids (2.2–7), ash (4–6) Shell and tail: moisture (58–68), protein (8–11.3), lipids (0.4–0.8), ash (8.5–13.5) | Endogenous proteases activity, polyphenoloxidase activities, appearance of melanin (black spot), soft shell, antibiotic residue, heavy metals contaminants (cadmium, arsenic, mercury, lead) | Cold chain, frozen storage, use of by-products from extensive shrimp farming (no antibiotic use), raw material safety through suppliers agreement | [3,64,65] |

| Crab (Portunus sp., Polybius sp., Cancer sp., Eriocheir sp., Eriphia sp.) | >50 | Shells, liver (hepatopancrease), physiological liquid (hemolymph), legs | Moisture (50–58), protein (15–30), minerals (30–50), chitin (15–30), fat (1–10) | Heavy metals (arsenic, cadmium, lead, chromium, mercury), loss of freshness (histamine, cadaverine, etc.), autolysis mediated by endogenous proteases | Storage at low temperatures, maintaining freshness, reject batch with high heavy metals | [66,67] |

| Lobster (Panulirus spp., Jasus sp.) | 45–80 | Head (20), shell, liver, eggs, hemolymph | Protein: heads (43.5), livers (41.1), shells (29} Lipids: liver (24.3), shells (0.6) Minerals: shells (36), heads (31.6) | Heavy metals (arsenic, cadmium, lead, chromium, mercury) due to marine pollution, loss of freshness (histamine, cadaverine, etc.), autolysis mediated by endogenous proteases, TMA formation | Storage at low temperatures, maintaining freshness, reject batches with high heavy metals | [66,67,68] |

| Cephalopods | ||||||

| Squid (Loligo sp., Illux sp.) | 52 | Heads and tentacles (25), fins (15), viscera (8), skins (3), pen (1) | Moisture (80) protein (18), lipids (1), ash (1) | Rapid post-mortem auto-proteolytic degradation of proteins, microbial spoilage; contamination by persistent organic pollutants (POP); high concentrations of copper, zinc, and cadmium in digestive glands | Keeping freshness, reducing the rate of chemical and microbial spoilage, cold storage, removing dark ink, reject batch contaminated with high concentrations of heavy metals | [69] |

| Cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) | 58 | Head and tentacles (23.3), viscera (18.7), fins (8.5), skin (4.2), ink (4.6) | Moisture (64–75), protein (14.9–17.5), lipids (4.8–6.2), ash (1.7–2.0) | Inappropriate storage temperature, degradation by acid and alkaline proteolytic activity, microbial spoilage, high quantity of heavy metals such as in viscera | Maintaining freshness of by-products; minimizing enzymatic degradation and microbial spoilage, especially in viscera, preservation, and cold storage of by-products | [52,70,71,72,73] |

| Bivalve mollusks | ||||||

| Oyster (Pinctada fucata), mussle (Mytilus edulis), cockle (Cerastoderma edule) | ~60 | Shell (60), byssus threads, extracellular fluid (containing hemolymph and extrapallial fluid (EP)) | Shell: protein (2.5% on a dry weight basis) | Contamination by heavy metals, gasoline, hydrocarbons, pesticides, and microorganisms (coliforms, vibrio, salmonella, shigella, biotoxins) | Monitoring concentrations in the laboratory each season, reject batches, use of disinfected water and refrigeration, implementation of good hygiene and manufacturing practices, fishermen’s health certificates | [74,75,76] |

| Marine Species | By-Product | Hydrolysis Conditions | Structural Properties of FPH/Peptides | Food Products | Storage Conditions | Oxidation Inhibition/Quality Preservation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amur sturgeon (Acipenser schrenckii) | Skin | Gelatin was hydrolyzed with Alcalase (5% w/w, pH 8.0, 50 °C) for 3 h | Pro-Ala-Gly-Tyr (405 Da) | Japanese seabass mince | Six freezing (−18 °C) and thawing (+4 °C) cycles | Peptide maintained intra-myofibrillar water (T21) pool and reduced free water (T22) population, preserved thermal properties of myosin and actin, and lowered TBARS formation | [11] |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Skin | Collagen was hydrolyzed with Alcalase at 4000 U/g and 60 °C for 3 h to obtain tilapia skin collagen peptide (TSCP) | Peptides with MW < 2.5 kDa accounted for 57.1% of TSCP, Gly accounted for 20.2% of amino acids, and the hydrophilic amino acids content was 38.3%. The active peptide was Asn-His-Gly-Lys (454 Da) | Scallop adductor muscles | −18 °C for 2 week | Frozen scallop muscles treated with 3 g/100 g TSCP showed higher salt soluble protein concentration, total sulfhydryl content, Ca2+-ATPase activity, and water-holding capacity during the 8 week storage period | [138] |

| Squid (Loligo opalescens) | Skin | Squid skin collagen was hydrolyzed with acid protease at 6000 U/g at 40 °C for 3 h to obtain collagen hydrolysates from squid skin (CH-SS) | 82.3% peptides had MW < 5000 Da, among them 22.69% had MW between 1–2 kDa; Asp-Val-Arg-Gly-Ala-Glu-Gly-Ser-Ala-Gly-Leu rich in Gly tripeptide repeat sequence was identified as the active peptide | Shrimp muscle | Fourteen freezing (−25 °C) and thawing (+4 °C) cycles | CH-SS reduced the mechanical injury caused by ice crystals to shrimp muscle as well as carbonyl formation, maintaining the integrity of fiber structure, thereby reducing drip loss, higher content of α-helix, and lower random coil compared to untreated muscle | [139] |

| Threadfin bream (Nemipterus hexodon) | Skin | Skin gelatin was hydrolyzed with lizardfish pepsin (pH 2.0 and 40 ◦C) and papain (pH 7.0 and 40 ◦C) for 60 min | Gelatin hydrolysates had a DH of 10, 20, 30, and 40% | Natural actomyosin (NAM) | NAM with 8% gelatin hydrolysates was subjected to six freeze-thaw cycles (20 h freezing at −18 °C and 4 h thawing at 4 °C for each cycle) | NAM with 20% DH gelatin hydrolysates showed the highest Ca2+-ATPase activity, total sulfhydryl groups and solubility along with lower disulfide bond content and TBARS | [140] |

| Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) | Muscle | Muscle homogenate was hydrolyzed with Protamex (1.5 AU/g) for 30 min at 50 °C | DH of the hydrolysates was 13.6 | Unwashed surimi | Storage at conventional (−18 °C) or ultra-low (−60 °C) temperatures and subject to three and six freeze–thaw cycles (per cycle −18/−60 °C, 12 h; 4 °C, 12 h) | Hydrolysates reduce the formation of carbonyls, TBARS, and volatiles hexanal, nonanal, and 1-octen-3-ol, while maintained total sulfhydryl group samples stored at −18 °C showed lower lipid and protein oxidation levels than those of samples stored at −60 °C, indicating structural deterioration of surimi under ultra-low frozen temperature storage | [141] |

| Silver carp | Meat leftovers on bones and heads | Defatted ground mince (5-folds isopropanol at 25 °C for 1 h) was hydrolyzed with Alcalase (AH; 3000 U/g; pH 8, 60 °C) or Protamex (PH; 2400 U/g, pH 7, 50 °C) for 30 min | DH for Alcalase and Protamex hydrolysates was 12.9 and 13.2% respectively, and peptides with MW of <138, 286–780, and ~1420 Da accounted for 3.5, 39.1, and 50.6% in Alcalase hydrolysates and 4.7, 16.8, and 37.4% in Protamex hydrolysates | Surimi | Surimi with 2, 4, and 6% hydrolysates subjected to six freeze–thaw cycles (−25 ± 1 °C for 12 h and 4 ± 1 °C for 12 h per cycle) | Surimi with the addition of 2 g of Protamex hydrolysate displayed the highest actomyosin extractability, Ca2+-ATPase activity and correspondingly, the lowest surface hydrophobicity of actomyosin, while maintaining total sulfhydryl groups and texture of heat-set gel | [142] |

| Large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) | Muscle | Lyophilized protein (0.02 mg/mL) was hydrolyzed with pepsin (pH 2, 40 °C), trypsin (pH 8, 45 °C, and neutral protease (pH 7, 50 °C) at 5000 U/g for 5 h | Peptides with MW < 500 Da comprised 77.8, 78.5, and 74.3% of pepsin, trypsin, and neutral protease hydrolysates, respectively, and trypsin hydrolysates showed the highest content of hydrophilic amino acids (51.87%) compared to pepsin (47.26%) and neutral protease (39.14%) hydrolysates | Turbot fillets | Fillets were soaked in 2 mg/mL hydrolysate alone or in combination with 4% sucrose) for 4 h, then subjected to 3 freeze–thaw cycles (−20 °C for 24 h and 4 °C for 12 h for each cycle) | Trypsin hydrolysates reduced the loss of Ca2+-ATP enzyme activity and the structural integrity damage of myofibrillar protein better than other hydrolysates | [143] |

| Argentine croaker (Umbrina canosai) | Muscle | Alkali-solubilized protein was hydrolyzed with Alcalase (pH 8, 50 °C) or Protamex (pH 7, 50 °C) at 30 U/g until a DH of 20% | MW of Alcalase and Protamex hydrolysates were 1083 and 1350 Da, respectively | Flounder fillets | Fillets coated with agar film containing Alcalase hydrolysates were stored at 5 °C for 15 days | Agar-hydrolysate film showed higher transparency and mechanical properties than clove essential oil film. It improved the biochemical and microbiological qualities of fillets without the sensory limitation of the essential oil volatile compounds | [144] |

| Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) | Skin | Gelatin was hydrolyzed by 2% (proten basis) Protamex® at pH 7 and 50 °C for 3 h | DPPH RSA, the metal chelating ability, and the FRAP of gelatin hydrolysates were 23.8%, 64%, and 2.65 μM TE/mg sample, respectively, and dipeptide Ala-Tyr (MW: 252 Da) was isolated as an active antioxidant peptide with FRAP of 89.3 μM TE/mg sample | Atlantic mackerel fillets | −18 °C/4 month | Ala-Tyr peptide layer on the furcellaran/gelatin hydrolysate (FUR/HGEL) films increased antioxidant activity and mechanical and rheological properties, while reducing the water solubility of the films; the reduction in fillet oxidation was not significant, and TVB-N formation was inhibited by the film | [145,146] |

| Blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou) | Discarded material | Hydrolysis by trypsin (0.1% E:S) at pH 8 and 50 °C until reaching a DH of 4% | EC50 values of DPPH RSA, reducing and chelating power were 1.46, 11, and 0.95 mg/mL, respectively. BPH contained 60% of peptides between 0.5 and 3 kDa. Protein, lipid, ash, and moisture were 76.8, 9.4, 7.3, and 3.35%, respectively | Omega-3 emulsion from refined commercial fish oil (18% EPA and a 12% DHA) | 20 °C/10 days | BPH increased its droplet size during storage while suffering significant lipid oxidation. However, it was not able to prevent omega-3 oxidation in spite of in vitro radical scavenging or chelating effect compared to whey (WPH) or soy (SPH) protein hydrolysates | [147] |

| Silver carp | Surimi processing by-products (SPB; head, skin, fin, scale, bone, white muscle leftover on bones, and dark muscle) | SPB was heated at 121 °C for 2 h, and lyophilized powder was hydrolyzed with Alcalase (55 °C, pH 8) and trypsin (37 °C, pH 8) for 4 h | Peptides with MW < 0.5 kDa accounted for 40.4 and 47.9% in trypsin (DH 13.4%) and Alcalase (DH 18.0%), hydrolyzed after 4 h, respectively | Surimi | −18 °C/3 month | Partial replacement of sucrose with 2% trypsin and Alcalase hydrolysates effectively delayed the oxidation of Cys, the carbonylation of amino acids, the loss of Ca2+-ATPase activity, and the destruction of the structural integrity of myofibrillar protein | [148] |

| Silver carp | Fins | Fins were dried, dispersed in distilled water (1:5, w/v), and heated at 121 °C for 3 h, and the obtained gelatin was hydrolyzed using four enzymes (Alcalase: pH 8.0 and 50 °C; trypsin: pH 8.0 and 37 °C; neutrase: pH 7.0 and 45 °C; and papain: pH 7.0 and 55 °C) at 2% for 4 h | A total of 102 and 61 peptides below 2 kDa were identified in trypsin and Alcalase hydrolysates, respectively, and some of the identified peptides shared similar repeated structures to Gly-Pro-X, such as Gly-Asp-Thr-Gly-Hyp-Ser-Gly-Hyp-Leu, Hyp-Gly-Hyp-Ile-Gly-Hyp-Hyp-Gly-Hyp-Arg, and Gly-Gly-Arg-Gly-Hyp-Hyp-Gly-Glu-Arg | Bighead carp fillets | Fillets were immersed in 2% of Alcalase or trypsin hydrolysates with higher antioxidant activity and were frozen at −18 °C for 1 week and thawed at 4 °C (once a week, as one freeze–thaw cycle) and a total of six cycles | Protein oxidation (carbonyls and disulfide bonds) and degradation (the loss of Ca2+-ATPase activity), and lipid oxidation (PV, TBARS, FFA, and fluorescent compounds) were significantly inhibited by fin hydrolysates | [149] |

| Silver carp | Surimi processing by-products | By-products powders were hydrolyzed with Alcalase at 1:60 w/w at pH 8.5 and 55 °C | -- | Surimi | Surimi mixed with 0.6 or 1.2% protein hydrolysates stored at −20 °C for 60 days | Surimi with protein hydrolysates showed lower TBARS, carbonyl content, and surface hydrophobicity; higher Ca2+-ATPase activity, total sulfhydryl groups, and salt-soluble proteins; and the reduced degradation of MP, thus inducing cross-linking more effectively, leading to the formation of a denser gel network | [150] |

| Silver carp | Muscle mince | Mince was hydrolyzed with Protamex (2400 U/g, pH 6.5, 50 °C) for 30 min and then fractionated into <3, 3–10, and >10 kDa fractions | DH was 13.6% and >50% peptides had an MW of 1000–2500 Da | Interactions between peptides and ice planes | Computational simulations | Gly-Val-Asp-Asn-Pro-Gly-His-Pro-Phe-Ile-Met, Gly-Val-Asp-Asn-Pro-Gly-His-Pro-Phe-Ile-Met-Thr, and Ile-Ile-Thr-Asn-trp-Asp-Asp-Met-Glu-Lys in the fractions with MW < 3 kDa interacted firmly with water molecules and inhibited the growth of ice crystals | [151] |

| Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis) | Gills | Gills were autoclaved (121 °C for 4 h to solubilize collagen) and hydrolyzed with Flavourzyme (pH 7.0), Alcalase (pH 8.0), neutral protease (pH 7.0), and papain (pH 7.0) at 5000 U/g for 4 h | Peptides with an MW of <0.5, 0–1, and 1–2 kDa were the dominant peptides, especially with increasing hydrolysis time | Surimi | Surimi (81% moisture) mixed with 1 or 2% neutral protease hydrolysates stored at −18 °C for 4 months | Surimi with hydrolysates had higher sulfhydryl and salt-soluble proteins and Ca2+-ATPase activity, lower disulfide bonds, carbonyls, and hydrophobicity | [152] |

| Common carp | Skin | Single-layer biopolymer films: furcellaran + carp skin gelatin hydrolysate; two-layer films: furcellaran + carp skin gelatin hydrolysate + Ala-Tyr | Synthetic Ala-Tyr peptide | Atlantic mackerel carcasses | Storage 4 °C, 15 days | Single- and double-layer coatings decreased lipid oxidation, but the addition of the peptide layer to the hydrolysate-furcellaran film did not improve its antioxidant effect | [153] |

| Pacific hake (Merluccius productus) | Fillets | Protamex (1%) was used to hydrolyze fillets for 1 h and with no pH adjustment (optimal condition) | Peptides were in the range of 95 to ~900 Da | Fish balls | Six freeze–thaw cycles (18 h at −25 °C and 6 h at 4 °C) | Protein hydrolysates decreased expressible moisture and cooking loss while maintaining salt-extractable proteins and the thermal properties of myosin | [154] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nikoo, M.; Regenstein, J.M.; Yasemi, M. Protein Hydrolysates from Fishery Processing By-Products: Production, Characteristics, Food Applications, and Challenges. Foods 2023, 12, 4470. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12244470

Nikoo M, Regenstein JM, Yasemi M. Protein Hydrolysates from Fishery Processing By-Products: Production, Characteristics, Food Applications, and Challenges. Foods. 2023; 12(24):4470. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12244470

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikoo, Mehdi, Joe M. Regenstein, and Mehran Yasemi. 2023. "Protein Hydrolysates from Fishery Processing By-Products: Production, Characteristics, Food Applications, and Challenges" Foods 12, no. 24: 4470. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12244470

APA StyleNikoo, M., Regenstein, J. M., & Yasemi, M. (2023). Protein Hydrolysates from Fishery Processing By-Products: Production, Characteristics, Food Applications, and Challenges. Foods, 12(24), 4470. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12244470